2.2

Changing Spaces

There has been a huge shift in the way we teach and learn. Boundaries are so blurred between working/learning and our social/home lives that they are often interchangeable and this has a big impact on the way we design buildings.

Changing Spaces explores the types of teaching and learning spaces we need to provide. What follows is an exploration of what future and emerging space types might be. These are broad and varied, and reflect the increasing importance of the student experience. This shift has also spawned a number of new hybrid building typologies such as ‘one-stop shop’ type student centres and innovation centres.

Before we explore this further, it is important to reflect on how our approach to a few key questions can influence the design.

Figure 2.4

Cooper Union New York: the successful integration of a large and complex academic brief into an urban context.

Iconography or Performance?

There can sometimes be conflicts between character and functional performance – especially in situations involving the retention of existing historic buildings or where a building needs to have significant presence in a campus. Recent years have seen a trend for universities to commission iconographic buildings, often by renowned architects. But if a ‘signature building’ approach is adopted this could also have limitations. Highly bespoke buildings may have less flexibility than a building focused on providing innovative learning spaces. That is not to say that such buildings do not work or do not have their place on campus, as they could often be highly successful in attracting leading researchers and funding. It is all a question of how we measure performance and value. Do we want to provide innovative spaces which improve learning outcomes or drive up our presence in a crowded international market? Without significant design investment it may be difficult to deliver both.

Some universities have a legacy of listed structures which are part of its historic fabric. These can be expensive to maintain and difficult to convert, but can also provide important iconic landmarks for the university. Here a ‘best fit’ approach should be adopted, avoiding complex retrospective installations of servicing and finding alternative, more compatible uses, such as collaborative learning. This additional constraint often means less efficient spaces but can also add character and identity.

Figure 2.5 Kings College London Learning Centre, BDP

Highly Defined or Ultimately Flexible?

Highly specialist spaces will, by their nature, have limited flexibility as they are characterised by their specific functional requirements. However, even within these limitations there has been extensive development in terms of furniture and specialist fittings, which can allow for changes to the ‘settings’, but these come at a cost.

Figures 2.6 and 2.7 Coventry University: flexible lecture theatres - Arup Associates

Providing flexibility is a dilemma. There is a risk that in attempting a high degree of flexibility, there will be a compromise when compared with a space designed for a single specific use. No one can predict future changes in technology, which has a huge impact on the design. Flexibility also requires more space to allow for differing layout configurations.

Low-Tech or Tech-Dependent?

Figure 2.8

Harvard University technical enhanced learning space, Shepley Bulfinch

Figure 2.9

Cooper Union, New York, Morphosis - wireless connection enables working anywhere

Advances in technology have played a big part in the expansion of learning opportunities. They have transformed the way we interact with each other and how we learn. How much should we invest in the hardware that we provide to support learning? Technology can sometimes define the spaces required (for example TEAL – Technology Enabled Active Learning) and that can prove tricky; the future is unpredictable and technology is expensive. Defining spaces by technology often requires additional technical support and could lead to future obsolescence.

We now expect all areas of the campus to be connected through wireless networks but this also extends out into wider communities. The increasing use of mobile devices provides improved flexibility and reduces the need for specialist furniture and equipment. However, charging devices can still be an issue and the ever-increasing reliance on WiFi increases the demand on our infrastructure.

Seclusion or Inclusion?

Learning is becoming less a singular endeavour and more a shared collaborative experience. This is aptly demonstrated by the democratisation of traditional teaching spaces to promote dialogue and, more importantly, the rise of social learning spaces across the campus. But have we gone too far? Social learning space is in high demand and its provision is still increasing but we need to ensure we are catering for differing learning styles. A balance needs to be struck with the provision of personal space to ensure this is not forgotten/undervalued in this wave of change. How do we get this balance right?

Single Use or Multi-Functional?

Spaces have been traditionally analysed by type or function. More recently, we have seen a move away from traditional categorisations of space in response to social, pedagogical and economic changes. The university curriculum is constantly shifting to meet emerging trends, new technologies and market demands and this affects the spaces and places required to support the teaching, learning and research.

There is also a blurring of boundaries between learning and social spaces as we now recognise that technology allows learning to happen virtually anywhere. This can be seen as a positive shift in the way we approach future developments; allowing greater flexibility to balance constantly pressurised space requirements through shared use.

Perhaps it is time for us to re-think briefing based on activities needed to support the curriculum, as developed in Part 3.

Figure 2.10, 2.11 and 2.12 The Why Factory TU Delft – MVRDV: multi functional space

Types of Learning Spaces

Space can be categorised in a number of different ways.

Our intention is not to replicate well-publicised research in detail but to provide an overview of the different space types which may be required, working from the more specific to the more generic typologies.

Rather than looking at traditional space typologies, this has therefore been approached from a broader perspective, categorising spaces as:

- • Specialist

- • Teaching

- • Collaborative

- • Personal.

This frees up any preconceptions about these spaces as traditional ‘rooms’ and it encourages us to think of the activities we need to support.

There is an increasing hybridisation of spaces which are more flexible and can support many differing activities. For example, a lecture theatre with swivel seating can offer opportunities for collaborative learning, so it can be said to be multi-dimensional.

Flexibility is to be encouraged; as courses and curriculum changes develop over time, the physical estate will inevitably lag behind. The ability to utilise space in alternative ways allows the university to be swifter in responding to the curriculum needs. We outline the characteristics of spaces and then explore further how these may be multi-functional on pages 32 and 33.

Specialist

Spaces which have specific functional/performance requirements typically: laboratories, lecture theatres, workshops, serviced studio spaces

Their limited spatial flexibility can lead to under-utilisation. To counter this they need to become more flexible and/or more intensively used. Additional flexibility can be provided through flat floors, more open orientation and use of furniture. Group sizes are typically medium to large.

Teaching

Spaces for the exchange of ideas: there is a move away from tutor- to student-centred learning, a transformation to more open participatory layouts, and the emergence of collaborative learning. This typically increases space standards and the need for increased flexibility, with TEAL. Group sizes can range from small to medium.

Collaborative

Spatial settings that foster a balanced dialogue between students and teachers, and also peer-to-peer learning. This may describe spaces where student groups meet for collaboration or where tutors engage with students informally.

Layouts can range from small group working spaces (either fully or partially enclosed) to larger open areas – the ‘kitchen table’ approach to larger social learning spaces.

Personal

Spaces for independent learning a place of retreat, reflection and quiet study. Traditionally, these would be reading rooms in libraries or bedrooms. Contemporary settings now utilise furniture to define these zones in many different spaces. This has led to a new breed of specialist furniture. We are just as likely to utilise public spaces such as coffee shops to provide this activity because, for most people, retreating from the usual workplace and setting is sufficient distance to create this environment. For quick tasks, drop-in points can be provided to allow for rapid access to the internet/resources.

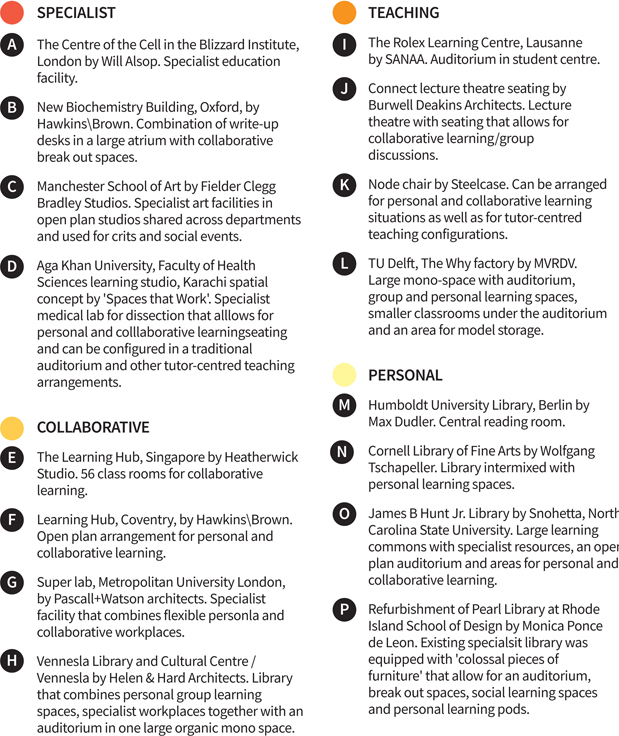

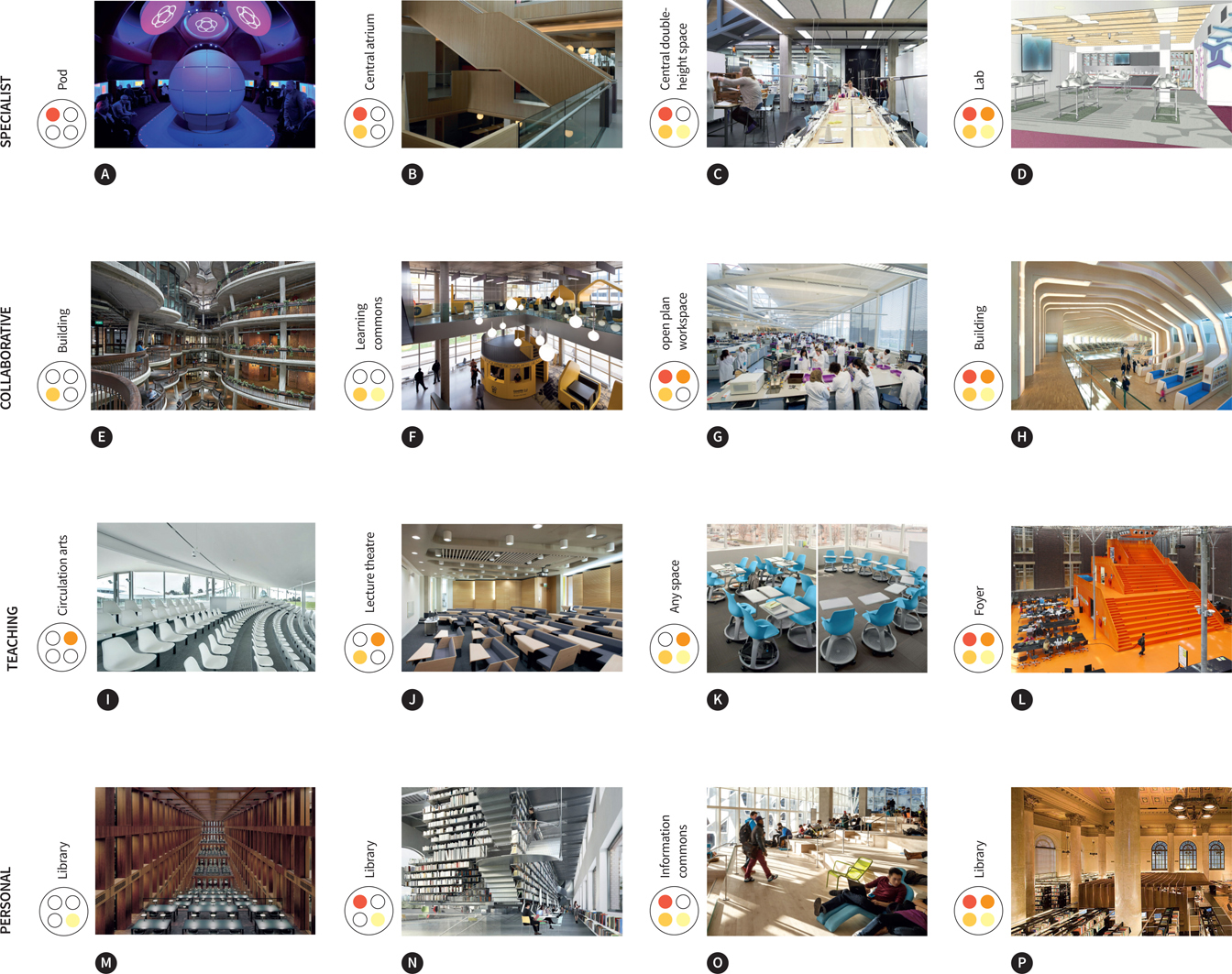

Figures 2.13

Types of learning spaces

Figures 2.14

The Hybridisation of Social and Learning Activity

Space types are not only merging into hybrid typologies but there appears to be a trend towards larger spaces, utilising furniture to define boundaries/zones which has created a new spatial paradigm. Furniture can provide the ‘setting’ to define both space and use in a way which would not have been conceivable 20 years ago. It should not, however, be seen as a panacea – specialist furniture can be expensive and the more complex it is, the less flexible it becomes. Mobility and standardisation of components are key in maximising the adaptability of space.

Figure 2.15

Breaking Boundaries

What is clear from recent experience is that there is a shift away from the traditional model of spaces and ownership (with spaces being owned by faculties or departments) towards a greater variety of more flexible shared spaces which respond to the increase in collaboration and peer-to-peer learning. This allows for departmental expansion and contraction, and provides increased opportunities for interaction and serendipity through shared use of space.

Success is not just governed by the types of space we provide but how we treat their interfaces – blurring the boundaries between uses through dispersed social learning creates activity across the campus.

Providing Variety and Balance of Spaces

While pedagogy will continue to evolve, there will be a need for the types of space covered here. Research is becoming more specialised, so it is unlikely that we are looking at the death of the mono-dimensional space. We are likely to see the continuing rise of more open collaborative learning areas. Clustering differing space types together can provide flexibility without making every space multi-functional.

We should take care that the shift to collaborative spaces is balanced with smaller personal spaces – we all need somewhere to retreat to for more intensive/quiet work. Getting this balance right may take time as a collaborative culture develops. We should consider a Soft Landings programme for new innovative environments. This would allow us to ‘fine-tune’ spaces as users settle into their new environments and use them in ways we had not anticipated when we designed them – such as a change in configuration, additional furniture/equipment, etc.

Space standards are constantly under review and optimising utilisation rates should come not just from within the estate but looking more widely into community/industry to provide compatible opportunities to learn and share knowledge, training and experience.

We must also not forget the ‘softer’ aspects of this in terms of design quality, the creation of places which inspire and engage people, whether it be through building form, furniture or materials or more intangible aspects such as character, light and feel.

Innovation and Change

How far should we innovate? Should we go back to low-tech?

In terms of innovative learning space and new technologies can be problematic but if successful there are great benefits in being ahead of your peers. Encouraging research and testing into the design of learning spaces, gathering feedback from students and staff can foster ownership and engagement in a longer-term project. Greater collaboration through interactive learning requires compatible connectivity. Experience has taught us that building capacity into the infrastructure is where money should be focused. Mixing high-and low-tech approaches allows for a mix of working styles and appeals to a wider range of users, and can add a richness and texture.

Future-Proofing

We need to recognise that spaces are temporary; they will need to adapt and change over their lifetime. If we approach projects with a longer-term view, we can devise sustainable strategies which will safeguard the future. This need not be expensive or specialist, and in many ways concentrating on efficient layouts, plan depths, good lighting and ventilation strategies is the most effective approach for long-term planning. We can reasonably assume that the trend towards greater mobility in technology will continue. Complex and expensive multi-use partitioning, interactive systems and multi-functional spaces should be carefully considered during project planning because, on large-scale projects, technology and pedagogy may have already moved on by the time the buildings are handed over.

We should think holistically about space provision. Look for new and interesting opportunities; consider more conversions of existing structures. Many post-war buildings are very robust concrete-framed constructions with generous ceiling heights and convert very well to provide contemporary learning spaces.

New extensions can provide any highly specialist requirements. A more pragmatic approach may be to make some key strategic decisions at ‘shell and servicing’ level – such as providing generous well proportioned spaces, while allowing for future flexibility in ‘scenery’ and ‘settings’; accepting that there is a long-term strategy and setting aside some funding for refresh.

Figure 2.16

James Stewart Centre for Mathematics, McMaster University, KPMB Architects. Juxtaposition of the new and the traditional. Tactile blackboards provide opportunity to capture those ‘lightbulb’ moments

Is this the Demise of the Physical Estate?

The way we learn is constantly shifting due to changes in pedagogy and is shaped by the advancing technology which allows for learning to happen in many different environments, often remote from the institutions themselves. If taken to its logical conclusion, we could argue that the university estate could actually reduce in scale if Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) take-up increases, as technology makes these virtual connections more viable. However, students choose universities on the basis of a wider ‘life’ experience, so while obviously the ‘formal’ curriculum – the teaching, learning and research on offer – is important, this may well be gauged alongside other factors such as the environment in which it is delivered, and the personal contact and experiences which are important to our lives. The quality and variety of learning spaces could be the differentiating factor in student decision-making. It could set the university apart and demonstrate a value in the ‘student life’ experience at a time when attending university is a major investment. It is therefore more likely that the estate may be extend out of its traditional campus boundaries creating satellite hubs and links with community where students can be supported in their online learning, as outlined in Jonas Nordquist’s networked learning landscape (page 153).

Impacts on Space

The following sections look at a variety of spatial functions where spaces and their furniture and equipment arrangements are developing in response to the changing patterns of student life, learning and research described above.

Each space type is analysed to see where they are still required to deliver very particular specialist functional performance for research or teaching requirements, and where they are becoming more hybrid, encouraging overlapping uses and enabling potentially more collaborative work styles alongside the requirements for personal study.