Imperfect Competition in the Labor Market

Manning Alan1, Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE

Abstract

It is increasingly recognized that labor markets are pervasively imperfectly competitive, that there are rents to the employment relationship for both worker and employer. This chapter considers why it is sensible to think of labor market as imperfectly competitive, reviews estimates on the size of rents, theories of and evidence on the distribution of rents between worker and employer, and the areas of labor economics where a perspective derived from imperfect competition makes a substantial difference to thought.

Keywords

Imperfect competition; Labor markets; Rents; Search; Matching; Monopsony

Introduction

In recent years, it has been increasingly recognized that many aspects of labor markets are best analyzed from the perspective that there is some degree of imperfect competition. At its most general, “imperfect competition” should be taken to mean that employer or worker or both get some rents from an existing employment relationship. If an employer gets rents, then this means that the employer will be worse off if a worker leaves i.e. the marginal product is above the wage and worker replacement is costly. If a worker gets rents then this means that the loss of the current job makes the worker worse off—an identical job cannot be found at zero cost. If labor markets are perfectly competitive then an employer can find any number of equally productive workers at the prevailing market wage so that a worker who left could be costlessly replaced by an identical worker paid the same wage. And a worker who lost their job could immediately find another identical employer paying the same wage so would not suffer losses.

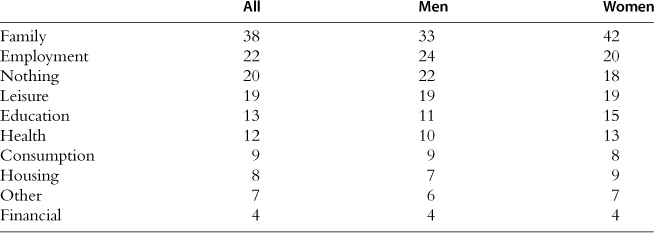

A good reason for thinking that there are rents in the employment relationship is that people think jobs are a “big deal”. For example, when asked open-ended questions about the most important events in their life over the past year, employment-related events (got job, lost job, got promoted) come second after “family” events (births, marriages, divorces and death)—see Table 1 for some British evidence on this. This evidence resonates with personal experience and with more formal evidence—for example, the studies of Jacobson et al. (1993) and Von Wachter, Manchester and Song (2009) all suggest substantial costs of job loss. And classic studies like Oi (1962) suggest non-trivial costs of worker replacement.

Table 1

Self-reported important life events in past year: UK data.

Source: British household panel study.

This chapter reviews some recent developments in thinking about imperfect competition in labor markets. The plan is as follows. The next section outlines the main sources of rents in the employment relationship. The second section discusses some estimates of the size of rents in the employment relationship. The third section then consider theoretical models of how the rents in the employment relationship are split between worker and employer (the question of wage determination) and the fourth section considers evidence on rent-splitting. I argue that this all adds up to a persuasive view that imperfect competition is pervasive in labor markets. But, up to this point, we have not considered the “so what” question—how does the perspective of imperfect competition alter our views on substantive labor market issues?—that is the subject of the fifth section. The sixth section then reviews a number of classic topics in labor economics—the law of one wage, the effect of regulation, the gender pay gap, human capital accumulation and economic geography—where the perspective of imperfect competition can be shown to make a difference.

This chapter is rather different in style from other excellent surveys of this area (e.g. Rogerson et al., 2005 or Mortensen and Pissarides, 1999 or Mortensen, 1986). Much work in this area is phrased in terms of canonical models—one might mention the search and matching models of Pissarides (1985, 2000) or Mortensen and Pissarides (1994) or the wage-posting model of Burdett and Mortensen (1998). New developments are often thought of as departures from these canonical models. Although the use of very particular models encourages precise thinking, that precision relates to the models and not the world and can easily become spurious precision when the models are very abstract with assumptions designed more for analytical tractability than realism. So, a model-based approach to the topic is not always helpful and this survey is based on the beliefthat it can be useful to think in very broad terms about general principles and that one can say useful things without having to couch them in a complete but necessarily very particular model.

1 The sources of imperfect competition

As will be discussed below there are different ways in which economists have sought to explain why there are rents in the employment relationship. This section will argue they are best understood as having a common theme—that, from the worker perspective, it takes time and/or money to find another employer who is a perfect substitute for the current one and that, from an employer perspective, it is costly to find another worker who is a perfect substitute for the current one. And, that, taken individually, these explanations of the sources of rents often do not seem particularly plausible but, taken together, they add up to a convincing description of the labor market.

1.1 Frictions and idiosyncracies

First, consider search models (for relatively recent reviews see Mortensen and Pissarides, 1999; Rogerson et al., 2005). In these models it is assumed that it takes time for employers to be matched with workers because workers’ information about the labor market is imperfect (an idea first put forward by Stigler, 1961, 1962)—in some versions, the job offer arrival rate can be influenced by the expenditure of time and/or money (see Section 2.2.1 below for such a model). These models have become the workhorse model in much of macroeconomics (see Rogerson and Shimer, 2011) because one cannot otherwise explain the dynamics of unemployment. But, taken literally, this model is not very plausible. It is not hard to find an employer—I can probably see 10 from my office window. But, what is hard is to find an employer who is currently recruiting2 who is the same as my current one i.e. a perfect substitute for my current job. This is because there is a considerable idiosyncratic component to employers across a vast multitude of dimensions that workers care about. This idiosyncratic component might come from non-monetary aspects of the job (e.g. one employer has a nice boss, another a nasty one, one has convenient hours, another does not) or from differences in commuting distances or from many other sources. A good analogy is our view of the heavens: the stars appear close together but this is an illusion caused by projecting three dimensions onto two. Neglecting the multitude of dimensions along which employers differ that matter to workers will seriously overestimate our impression of the extent to which jobs are perfect substitutes for each other from the perspective of workers.

One other commonly given explanation for why there may be rents in the employment relationship is “specific human capital”. Although this is normally thought of as distinct from the reasons given above, it is better thought of as another way in which employers may not be perfect substitutes for each other—in this case in terms of the quality of the match or the marginal product of the worker. This comes out clearly in the discussion of specific human capital provided by Lazear (2003). He struggles with the problem of what exactly are specific skills, coming up with the answer that “it is difficult to generate convincing examples where the firm-specific component [of productivity] approaches the general component”. He goes on to argue that all skills are general skills but that different employers vary in how important those skills are in their particular situation. So, a worker with a particular package of general skills will not be faced with a large number of employers requiring exactly that package. As Lazear (2003, p. 2) makes clear, this relies on employers being thin on the ground otherwise a large supply of employers demanding exactly your mix of skills would be available and the market would be perfectly competitive. Again, it is the lack of availability of employers who are perfect substitutes that can be thought of as the source of the rents.

A key and eminently sensible idea in the specific human capital literature originating in Becker (1993) is that specific human capital accumulates over time. This means that rents in the employment relationship are likely to be higher for those workers who have been in their current job for a long time—very few labor economists would dissent from this position. The very fact that we turn up to the same employer day after day strongly suggests there are some rents from that relationship. More controversial is whether, on a worker’s first day in the job, there are already rents because the employer has paid something to hire them and the worker could not get another equivalent job immediately. This paper is predicated on the view that there are rents from the first day3 – that the worker would be disappointed if they turned up for work to be told there was no longer a need for them and that the employer would be irritated if the new hire does not turn up on the first morning.

One interesting question to think about is whether the rapid decline in the costs of supplying and acquiring information associated with the Internet is going to make labor markets more like the competitive ideal in the future than the past. There is no doubt that the Internet (and earlier communication technologies) have transformed job search. In late 19th century London an unemployed worker would have trudged from employer to employer, knocking on doors and enquiring whether there were any vacancies, often spending the whole day on it and walking many miles. In contrast, a worker today can, with access to the Internet, find out about job opportunities throughout the globe. Using the Internet as a method of job search has rapidly become near-universal. For example, in the UK Labour Force Survey the percentage of employed job-seekers using the Internet rose from 62% in 2005 to 82% in 2009 and the percentage of unemployed job-seekers using the Internet rose from 48% to 79% over the same period. These figures also indicate that the “digital divide”, the gap in access to the internet between the rich and the poor, may also be diminishing.

But, while there is little doubt that Internet use is becoming pervasive in job search, there is more doubt about whether it is transforming the outcomes of the labor market. Autor (2001) provides a good early discussion of the issues. While the Internet has increased the quantity of information available to both workers looking for a job and employers looking for a worker has gone up, it is much less clear that the quality has also risen. If the costs of applying for a job fall then applications become particularly more attractive for those who think they have little chance of getting the job—something they know but their prospective employer may only discover at some expense. One way of assessing whether the Internet has transformed labor markets is to look at outcomes. Kuhn and Skutterud (2004) do not find a higher job-finding rate for those who report using the Internet and the Beveridge curve does not appear to have shifted inwards.

So, the conclusion would seem to be that the Internet has transformed the labor market less than one might have thought from the most common ways in which frictions are modeled. If one thinks of frictions as being caused by a lack of awareness of where vacancies are, and the cost of hiring the cost of posting a vacancy until a suitable job application is received, then one might have expected a large effect of the Internet. But if, as argued here and later in this chapter, one thinks of frictions as coming from idiosyncracies in the attractiveness of different jobs, and the costs of hiring as being primarily the costs of selection and training new workers, then one would be less surprised that the effects of the Internet seem to be more modest.

1.2 Institutions and collusion

So far, the discussion has concentrated on rents that are inevitable. But rents may also arise from man-made institutions that artificially restrict competition. This implicit or explicit collusion may be by workers or employers. Traditionally it is collusion by workers in the form of trade unions that has received the most attention. However, this chapter does not discuss the role of unions at all because it is covered in another chapter (Farber, 2011).

Employer collusion has received much less attention. This is in spite of the fact that Adam Smith (1970, p. 84) wrote: “we rarely hear... of the combinations of masters; though frequently of those of workmen. But whoever imagines, upon this account, that masters rarely combine, is as ignorant of the world as of the subject”. Employer collusion where it exists is thought to be in very specific labor markets e.g. US professional sports or, more controversially, nurses (see, for example, Hirsch and Schumacher, 1995) and teachers who may have a limited number of potential employers in their areas (see Boal and Ransom, 1997, for a discussion).

There a number of more recent papers arguing that some institutions and laws in the labor market serve to aid collusion of employers to hold down wages. For example, Naidu (2010) explores the effect of legislation in the post-bellum South that punished (almost exclusively white) employers if they enticed (almost exclusively black) workers away from other employers. Although it might appear at first sight to be white employers who suffered from this legislation, Naidu (2010) presents evidence that, by reducing competition for workers, it was blacks who were made worse off by this. The legislation can be thought of as a way for employers to commit not to compete for workers, leading to a more collusive labor market outcome.

A more contemporary example would be the debate over the “National resident Matching Program” (NMRP) that matches medical residents and hospitals. In 2002 a class action suit was brought against hospitals alleging breach of anti-trust legislation, essentially that the NMRP enabled hospitals to collude to set medical resident wages at lower than competitive levels. This case was eventually resolved by Congress passing legislation that effectively exempted the NMRP from anti-trust legislation (details of this can be found at http://kuznets.fas.harvard.edu/~aroth/alroth.html#MarketDesign). There is some theoretical work (e.g. Bulow and Levin, 2006; Niederle, 2007) arguing whether, in theory, the NMRP might reduce wages. These papers look at the incentive for wage competition within the NMRP. More, recently Priest (2010) has argued that the “problems” of the labor markets for medical interns (which have led to the use of matching algorithms like the NMRP) are in fact the consequences of employer collusion on wages in a labor market with very heterogeneous labor and that a matching algorithm would not be needed if the market was allowed to be competitive. He also argues that the market for legal clerks is similar.

Another recent example is Kleiner and Won Park (2010), who examine how different state regulations on dentists and dental hygienists affect the labor market outcomes for these two occupations. They present evidence that states which allow hygienists to practice without supervision from dentists (something we would expect to strengthen the market position of hygienists and weaken that of dentists) have, on average, higher earnings for hygienists and lower earnings for dentists.

All of these examples relate to very specific labor markets that might be thought to all be highly atypical. But there remains an open question as to whether employer collusion is important in more representative labor markets. It is clear that employers do not en masse collude to set wages, but there may be more subtle but nevertheless effective ways to do it. For example, as the physical location of employers is important to workers, it is likely that, for many workers, the employers who are closest substitutes from the perspective of workers are also geographically close, making communication and interaction between them easy. Manning (2009) gives an example of a model in which employers are on a circle (as in Bhaskar and To, 1999) and collude only with the two neighboring employers in setting wages. Although there is no collusion spread over the whole market, Manning (2009) shows that a little bit of collusion can go a long way leading to labor market outcomes a long way from perfect competition. One way of putting the question is “Do managers of neighboring fast food restaurants talk to each other or think about how the other might react if wages were to change?”. Ethnographic studies of labor markets may give us some clues. The classic study of the New Haven labor market in Reynolds (1951) did conclude there was a good deal of discussion among employers about economic conditions, and that there was an implicit agreement not to poach workers from each other. One might expect this to foster some degree of collusion though Reynolds (1951, p. 217) is clear that there is no explicit collusive wage-setting. In contrast, the more recent ethnographic study of the same labor market by Bewley (1999) finds that the employers source of information about their rivals comes not from direct communication but from workers or from market surveys provided by consultancies. Those institutions sound less collusive than those described by Reynolds. But, the honest answer is that we just don’t know much about tacit collusion by employers because no-one has thought it worthwhile to investigate in detail.

2 How much imperfect competition? the size of rents

A natural question to ask is how important is imperfect competition in the labor market? As explained in the introduction, this is really about the size of rents earned by employer and worker from an on-going employment relationship. The experiment one would like to run is to randomly and forcibly terminate employment relationships and examine how the pay-offs of employer and worker change. We do not have that experiment and, if we did, it would not be that easy to measure the pay-offs which would not just be in the current period but also into the future.

Nonetheless we can make some attempt to measure the size of rents, and this section illustrates the way in which we might attempt to do that. First, we seek to exploit the idea that the larger the size of rents, the more expenditure on rent-seeking activity we would expect to see—we use this idea from both worker and employer perspectives. Second, we consider what happens when workers lose their jobs. Before we review these estimates, one should be aware that there is almost certainly huge variation in the extent of rents in the labor market so that one has to bear in mind that the estimates that follow are not from random samples and should not automatically be regarded as representative of the labor market as a whole. And, as will become apparent, these estimates are pretty rough and ready, and should be interpreted as giving, at best, some idea of orders of magnitude.

2.1 The costs of recruitment

2.1.1 Theory

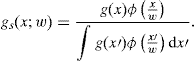

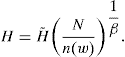

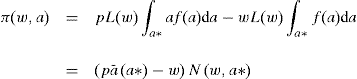

First, consider how we might attempt to measure rents from the perspective of employers. If an employer and worker are forcibly separated then a good estimate of the size of the rents is the cost of replacing the worker with an identical one—what we will call the marginal hiring cost. Using the marginal hiring cost as a measure of employer rents is quite a general principle but let’s see it worked out in a specific model, the Pissarides (1990) matching model. Denote by J the value of a filled job and Jυ the value of a vacant job—the size of the rents accruing to an employer can be measured by (J – Jυ). The value function of a vacant job must be given by:

![]() (1)

(1)

where r is the interest rate, c is the per-period cost of a vacancy and θ is the rate at which vacancies are filled. As firms can freely create vacant jobs (it is a filled vacancy that can’t be costlessly created) we will have Jυ = 0 in equilibrium, in which case (1) can be re-arranged to give us:

![]() (2)

(2)

which can be interpreted as saying that the value of a filled job to an employer is equal to the per period vacancy cost times the expected duration of a vacancy. This can be interpreted as the marginal cost of a hire. This latter principle can be thought of as much more general than the specific model used to illustrate the idea.

The specific model outlined here suggests a very particular way of measuring the rents accruing to employers—measure the cost of advertising a job and the expected duration of a vacancy. Both of these numbers are probably small, at least for most jobs (for example, the study of five low-wage British employers in Brown et al. (2001), found that the advertising costs were often zero because they used the free Public Employment Service). However, the way in which the hiring cost is modeled here is not the best. Actual studies of the costs of filling vacancies find that the bulk of the costs are not in generating applicants as this model suggests but in selecting workers from applicants and training those workers to be able to do the job4.

Even once one has got an estimate of the marginal hiring cost, which we will denote for the moment by h, one needs to scale it in some way to get an idea of how important they are. The natural way to do that would is to relate it to the wage, w. However, salary is a recurrent cost whereas the hiring cost is a one-off cost. How large are hiring costs depends in part on how long the worker will be with the firm. Given this it is natural to multiply the hiring costs by the interest rate plus the separation rate i.e. to use the measure (r + s)h/w. Because separation rates are often about 20% and much bigger than real interest rates, this is approximately equal to multiplying the hiring costs by the separation rate, (s * h/w) which can also be thought of as dividing the hiring cost by the expected tenure of the worker (which is 1/s), to give the hiring cost spread over each period the firm expects to have the worker. Another way of looking at the same thing is the share of wage payments over the whole job tenure that is spent on recruiting and training a worker. In a steady-state this will be equal to the ratio of total hiring costs to the current wage bill as the total hires must be equal to sN with total hiring costs sNh, compared to total wage bill wN, giving the same measure.

Hiring costs play an important role in macroeconomic models based on imperfect competition in the labor market deriving from search. These studies (e.g. Silva and Toldeo, 2009; Pissarides, 2009) generally choose to parameterize hiring costs differently—as the cost of posting a vacancy (c/θ in (2)) for a period relative to the wage for the same period. This can be converted to the measure proposed above by recognizing this needs to then be scaled by the expected duration of a newly-filled job (which is 1/s). So one can go from the measure I am reporting to the measure preferred by macroeconomists the importance of hiring costs by dividing by the expected duration of a job.

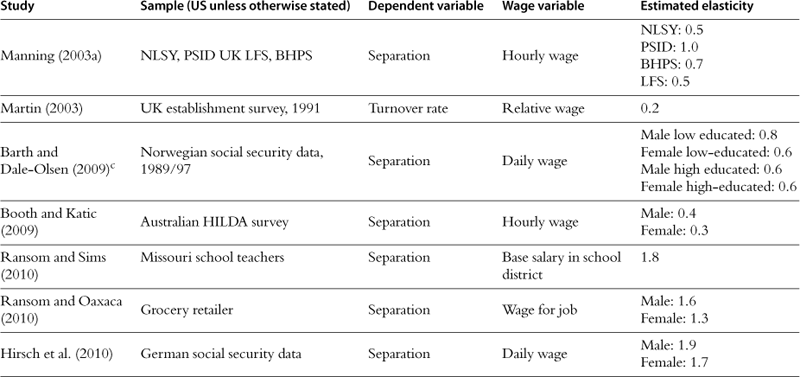

2.1.2 Evidence on hiring costs

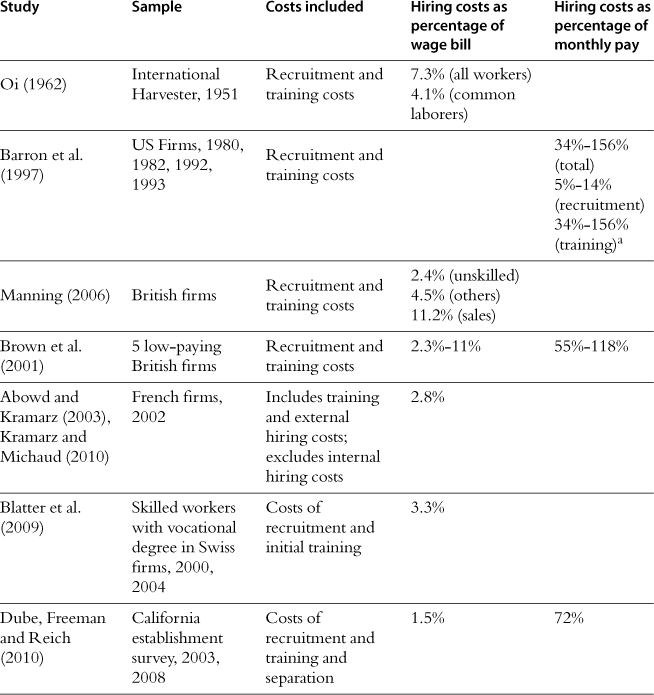

It is hard to get direct data on hiring costs and the estimates we do have are for very different times and places and from very different data sets. In a very brief review of some estimates, Hamermesh (1993, p. 208–9) noted the paucity and diversity of estimates and argued the problem derived from the difficulty of defining and measuring hiring costs. Not much has changed since then. Some estimates are summarized in Table 2, where we report two measures of the size of hiring costs—hiring costs as a percentage of total labor costs (the measure described above) and hiring costs as a percentage of monthly earnings. The second measure can be turned into the first by dividing by the expected duration (in months) of a job—this measure of job tenure is not available in all data sets (notably, Barron et al., 1997). Not all of the estimates measure all aspects of hiring costs and not all the studies contain enough information to enable one to compute both measures. For example, the French studies of Abowd and Kramarz (2003) and Kramarz and Michaud (2010) exclude the amount of time spent by workers in the firm on the recruitment process.

Table 2

aThis is an estimate derived from Table 7.1 of Barron et al. (1997), with the reported hours of those spent on the recruiting and/or training multiplied by 1.5, a crude estimate of the relative wage of recruiters/trainers to new recruits taken from Silva and Toldeo (2009). This is then divided by an assumption of a 40 hour week to derive the fraction of a month’s pay spent on recruiting/training.

Although there is a very wide range of estimates in Table 2, some general features do emerge. First, the original Oi (1962) estimates seem in the right ballpark—with hiring costs a bit below 5% of the total labor costs. The bulk of these costs are the costs associated with training newly-hired workers and raising them to the productivity of an experienced worker. The costs of recruiting activity are much smaller. We also have evidence of heterogeneity in hiring costs, both across worker characteristics (the hiring costs of more skilled workers typically being higher) and employer characteristics (the hiring costs of large employers typically being higher). But, one should recognize that we do not know enough about the hiring process—another chapter in this volume (Oyer and Schaefer, 2011) makes a similar point.

2.1.3 Marginal and average hiring costs

It is not entirely clear from Table 2 whether we have estimates of average or marginal hiring costs—from the theoretical point of view we would like the latter more than the former. In some surveys (e.g. Barron et al., 1997) the questions on hiring costs relate to the last hire, so the responses might be interpreted as a marginal hiring cost. In other studies (e.g. Abowd and Kramarz, 2003) the question relates to all expenditure on certain activities in the past year, so are more likely to be closer to average hiring costs. In others studies, it is not clear.

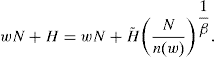

To think about the relationship between average and marginal hiring costs suppose that the total cost of R recruits is given by:

![]() (3)

(3)

Then there is the following relationship between marginal hiring cost and the average hiring cost:

![]() (4)

(4)

If β is below (above) 1 there are increasing (decreasing) marginal costs of recruitment, and the marginal cost will be above (below) the average cost.

We do have some little bits of evidence on the returns to scale in hiring costs. Manning (2006), Blatter et al. (2009) and Dube, Freeman and Reich (2010) all report increasing marginal costs, although the latter study finds that only in a cross-section. However, Abowd and Kramarz (2003) and Kramarz and Michaud (2010) report decreasing marginal costs, as they estimate hiring to have a fixed cost component. However, this last result may be because they exclude the costs of recruitment, where one would expect marginal costs to be highest. The finding in Barron et al. (1997) that large firms have higher hiring costs might also be interpreted as evidence of increasing marginal costs, as large firms can only get that way by lots of hiring. Our evidence on this question is not strong, and one cannot use these studies to get a reliable point estimate of β. One can also link the question of whether there are increasing marginal costs of hiring to the older literature on employment adjustment costs (e.g. Nickell, 1986; Hamermesh, 1993)—the traditional way of modeling these adjustment costs as quadratic corresponds to increasing marginal hiring costs.

Worrying about a possible distinction between marginal and average hiring costs might seem a minor issue, but Section 4.3.4 shows why it is more important than one might have thought for how one thinks about the nature of labor markets and the likely effects of labor market regulation.

2.2 The search activity of the non-employed

2.2.1 Theory

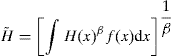

Now consider the size of rents from the perspective of workers. One cannot use a similar methodology to that used in the previous section because, while it is reasonable to assume that vacant jobs are in potentially infinite supply, one cannot make the same assumption about unemployed workers. The approach taken here is that if employment offers sizeable rents we would expect to see the unemployed making strenuous efforts to find employment and the size of those efforts can be used as a measure of the rents.

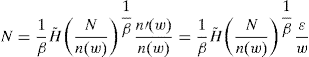

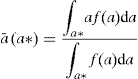

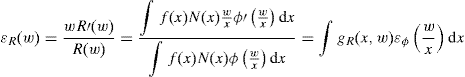

Consider an unemployed worker who faces a wage offer distribution, F(w), and can influence the arrival rate of job offers, λ, by spending time on job search. Denote by γ the fraction of a working week spent on job search and λ(γ) the function relating the job offer arrival rate to the time spent on job search. The value of being unemployed, Vu, can then be written as:

![]() (5)

(5)

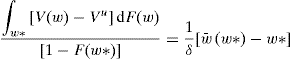

where r is the interest rate, bu is the income received when unemployed, b is the value of leisure, w* is the reservation wage (also a choice variable), and V(w) is the value of a job that pays a wage w. This is a set-up first used by Barron and Mellow (1979). Taking the first order condition for the time spent on job search, γ:

![]() (6)

(6)

This shows us that the incentive for workers to generate wage offers is related to the rents they will get from those offers. Let us rearrange (6) to give us:

(7)

(7)

where ελγ is the elasticity of the job offer arrival rate with respect to search effort and du is the expected duration of unemployment5.

The left-hand side of (7) is the rents from employment averaged over all the jobs the unemployed worker might get. This is unobservable and what we would like to estimate. Equation (7) says that these average rents should be equated to the monetary value of leisure multiplied by the expected total time spent searching until getting a job (which is the duration of unemployment multiplied by time per week spent on job search) divided by the inverse of the elasticity of the job offer arrival rate to search effort. All of these elements are things that we might hope to be able to estimate, some more easily than others.

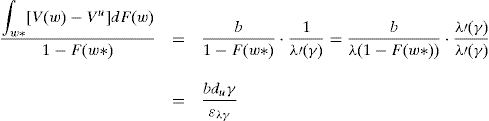

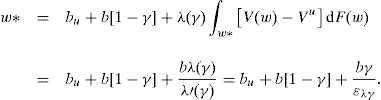

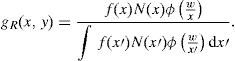

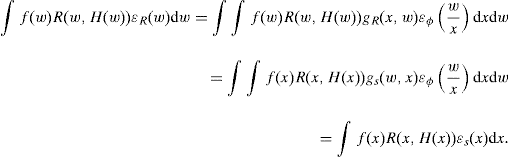

The intuition for (7) is simple—if workers typically get rents from jobs we would expect to see them willing to expend considerable amounts of time and money to get a job. However, to convert the right-hand side of (7) to monetary units we need a monetary value for leisure when unemployed. We would like to normalize these costs to get an estimate of the “per period” rent. Appendix A works through a very simple model to sketch how one might do that and derives the following formula for the gap between the average wage, ![]() , and the reservation wage, w*:

, and the reservation wage, w*:

![]() (8)

(8)

where ρ is the income when unemployed as a fraction of the reservation wage and u is the steady-state unemployment rate for the worker. The elements on the right-hand side of (8) are all elements we might hope to estimate.

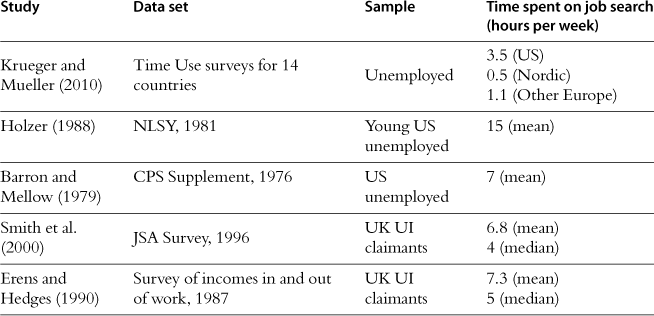

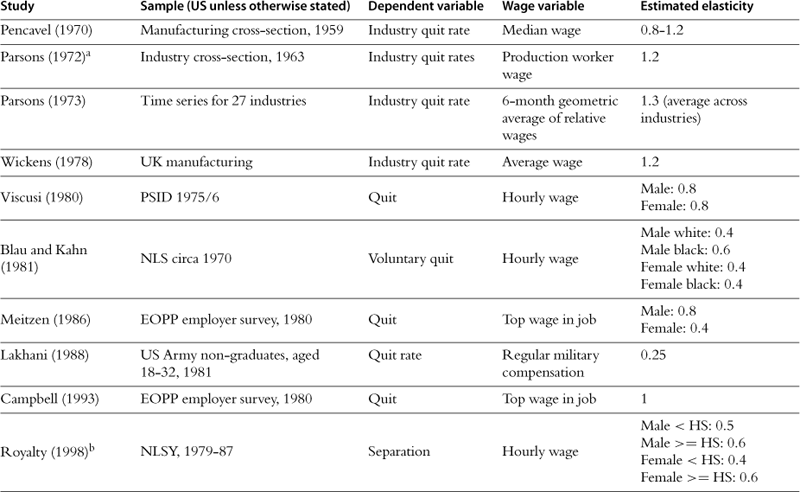

2.2.2 Evidence

A crucial element in (8) is the fraction of a working week that the unemployed spend on job search. Table 3 provides a set of estimates of the time spent on job search by the unemployed, though such estimates are not as numerous as one would like. Probably the most striking fact about the job search activity of the unemployed is often how small is the amount of time they seem to spend on it. The most recent study is the cross-country comparison of Krueger and Mueller (2010), who use time-use surveys to conclude that the average unemployed person spends approximately 4 minutes a day on job search in the Nordic countries, 10 minutes in the rest of Europe, and 30 minutes in North America. But the other US and UK studies reported in Table 3 find higher levels of job search6. These studies use a methodology where a direct question is asked of the unemployed about the amount of time spent searching, a very different methodology from the time-use studies. However, even these studies do not suggest a huge amount of time spent unemployed as it is essentially a part-time activity. Taking these numbers at face value they perhaps suggest a value for γ in the region of 0.1–0.2.

If one assumed that the steady-state unemployment rate for currently unemployed workers is 10%, and that the replacement rate was 0 and that ελγ was 1 so that a doubling of search effort leads to a doubling of the job offer arrival rate, one would conclude from the use of the formula in (8) that the rents for unemployed workers are small, no more than 2%. However, there are a number of reasons to be cautious about this conclusion.

First, the formula in (8) is very sensitive to the assumed value of ελγ. If increases in search time lead to little improvement in job offer arrival rates, a small amount of job search is consistent with large rents. Ideally we would like to have some experimental evidence on what happens when we force individuals to increase job search activity. Although there are a large number of studies (many experimental or quasi-experimental), that seek to estimate the effect of programmes designed to assist with job search on various outcomes for the unemployment, many of these job search assistance programs combine more checking on the job search activity of the unemployed with help to make search more effective. For current purposes we would like only the former. One study that seems to come close is Klepinger et al. (2002) which investigates the effect of Maryland doubling the number of required employer contacts from 2 to 4. This doubling of required contacts significantly reduced the number of weeks of UI receipt by 0.7 weeks on a base of 11.9 so a doubling in the required number of contacts reduces unemployment durations by 6%. Assuming that the doubling of the number of contacts doubles the cost leads to a very small implied elasticity of 0.04. There are a number of reasons to be cautious—we do not have evidence about how much employer contacts were actually increased and, second, when individuals are forced to comply with increased employer contacts they would not choose for themselves, they will probably choose low-cost but ineffective contacts. These would tend to lead to lower estimates of the elasticity. On the other hand exits from UI are not the same as exits to employment and the employment outcomes are not so favorable.

There are also a number of non-experimental studies that seek to relate unemployment durations to job search intensity, with mixed results that suggest caution in interpretation. For example, Holzer (1987) reports estimates for the effect of time spent on a variety of search methods on the probability of gaining new employment (though he also controls for the number of search methods used)—many of the estimated effects are insignificant or even “wrongly-signed”.

Secondly, the formula in (8) assumes that the cost of time in job search and employment can be equated. However, the time cost of job search may be higher than one might think as Krueger and Mueller (2010) find that levels of sadness and stress are high for the unemployed while looking for a job and levels of happiness are low. If these emotional costs are high, the cost of job search will be higher than one otherwise would have thought, reducing the incentives to spend time on it.

Thirdly, while job search seems to use more time than money (something that motivated the model used here), the monetary cost is not zero. While the unemployed have a lot of time on their hands, they are short of money. Studies like Card et al. (2007) suggest that the unemployed are unable to smooth consumption across periods of employment and unemployment so that the marginal utility of income for the unemployed may be much higher than for the employed. For example, in the UK evaluation of the Job Seekers’ Allowance, one-third of UI recipients reported that their job search was limited because of the costs involved, with the specific costs most commonly mentioned being travel, stationery, postage and phone. If time and money are complements in the job search production function, low expenditure will tend to be related to low time spent.

Finally, DellaVigna and Daniele Paserman (2005) investigate the effect of hyperbolic discounting in a job search model. They present evidence that, in line with theoretical predictions, the impatient engage in lower levels of job search and have longer unemployment durations. If this is the right model of behavior one would have to up-rate the costs of job search by the degree of impatience to get an estimate of the size of rents from jobs.

So, the bottom line is that although the fact that the unemployed do not seem to expand huge amounts of effort into trying to get employment might lead one to conclude that the rents are not large, there are reasons why such a conclusion might be hasty. And we do have other evidence that the unemployed are worse off than the employed in terms of well-being—see, for example, Clark and Oswald (1994), Krueger and Mueller (2010). I would be hesitant to conclude that the rents from employment are small for the unemployed because of the low levels of search activity as I suspect that if one told a room of the unemployed that their apathy showed they did not care about having a job, one would get a fairly rough reception. When asked to explain low levels of search activity, one would be much more likely to hear the answer “there is no point”, i.e. they say that the marginal return to more search effort, ελγ, is low.

One possible explanation for why the unemployed do not spend more time on job search is that the matching process is better characterized by stock-flow matching rather than the more familiar stock-stock matching (Coles and Smith, 1998; Ebrahimy and Shimer, 2010). In stock-flow matching newly unemployed workers quickly exhaust the stock of existing vacancies in which they might be interested and then rely on the inflow of new vacancies for potential matches. It may be that rapid exhaustion of possible jobs provides a plausible reason for why, at the margin, there is little return to extra job search.

Before we move on, it is worth mentioning some studies that have direct estimates of the left-hand side of (8). These are typically studies of the unemployed that ask them about the lowest wage they would accept (their reservation wage) and the wage they expect to get. For example Lancaster and Chesher (1983) report that expected wages are 14% above reservation wages. The author’s own calculations on the British Household Panel Study, 1991–2007 suggest a mean gap of 21 log points and a median gap of 15 log points. These estimates are vulnerable to the criticism that they are subjective answers, though the answers do predict durations of unemployment and realized wages in the expected way7. They are perhaps best thought of as very rough orders of magnitude

The discussion has been phrased in terms of a search for the level of worker rents, ignoring heterogeneity. However, it should be recognized that there are a lot of people without jobs who do not spend any time looking for a job. For this group—classified in labor market statistics as the inactive—the expected rents from the employment relationship must be too small to justify job search. The fact that some without jobs search and some do not strongly suggests there is a lot of heterogeneity in the size of rents or expected rents. Once one recognizes the existence of heterogeneity one needs to worry about the population whose rents one is trying to measure. The methodology here might be useful to tell us about the rents for the unemployed but we would probably expect that the average rents for the unemployed are lower than for the employed. Estimating the rents for the employed is the subject of the next section.

2.3 The costs of job loss

To estimate rents for the employed, the experiment one would like to run is to consider what happens when workers are randomly separated from jobs. There is a literature that considers exactly that question—studies of displaced workers (Jacobson et al., 1993; Von Wachter, Manchester and Song, 2009). One concern is the difficulty of finding good control groups, e.g. the reason for displacement is presumably employer surplus falling to less than zero. But, for some not totally explained reason, it seems that wages prior to displacement are not very different for treatment and control groups—it is only post-displacement that one sees the big differences. Under this assumption one can equate these estimates to loss of worker surplus.

For a sample of men with 5 years previous employment who lost their jobs in mass lay-offs in 1982, Von Wachter, Manchester and Song (2009) estimate initial earnings losses of 33% that then fall but remain close to 20% after 20 years. Similar estimates are reported in Von Wachter, Bender and Schmeider (2009) for Germany. These samples are workers who might plausibly be expected to have accumulated significant amounts of specific human capital, so one would not be surprised to find large estimated rents for this group. However, Von Wachter, Manchester and Song (2009) find sizeable though smaller earnings losses for men with less stable employment histories pre-displacement and for women. At the other extreme, Von Wachter and Bender (2006) examine the effects of displacement on young apprentices in Germany. For this group, where we would expect rents to be small, they find an initial earnings loss of 10%, but this is reduced to zero after 5 years.

We also have a number of other studies looking at how the nature of displacement affects the size of earnings losses. Neal (1995), and Poletaev and Robinson (2008) show that workers who do not change industry or occupation or whose post-displacement job uses a similar mix of skills have much smaller earnings losses. This is as one would expect given what was said earlier about the reason for rents being the lack of an alternative employer who is a perfect substitute for the present one. Those displaced workers fortunate enough to find another job which is a close substitute for the one lost would be expected to have little or no earnings loss. But, the sizeable group of workers whose post-displacement job is not a perfect substitute for the one lost will suffer larger earnings losses. For example, Poletaev and Robinson (2008) estimated an average cost of displacement for all workers of 7% but the 25% of workers who switch to a job with a very different skill portfolio suffer losses of 15%. The fact that 25% of workers cannot find a new job that is a close match to their previous one suggests there are not a large number of employers offering jobs that are perfect substitutes for each other.

2.4 Conclusions

The methods discussed in this section can be used to give us ballpark estimates of the extent of imperfect competition in labor markets. They perhaps suggest total rents in the 15–30% range with, perhaps, most of the rents being on the worker side. However, one should acknowledge there is a lot of variation in rents and enormous uncertainty in these calculations. Because we have discussed estimates of the rents accruing to employers and workers, one might also think about using these estimates to give us some idea of how the rents are split between worker and employer. However, because none of the estimates come from the same employment relationship, that would be an unwise thing to do. The next section discusses models of the balance of power between employers and workers and these are reviewed in the next section.

3 Models of wage determination

When there are rents in the employment relationship, one has to model how these rents are split between worker and employer, i.e. one needs a model of wage determination. This is a very old problem in economics in general and labor economics in particular, going back to the discussion of Edgeworth (1932), where he argued that the terms of exchange in a bilateral monopoly were indeterminate. That problem has never been definitively resolved, and that is probably because it cannot be. In this section we describe the two main approaches found in the literature and compare and contrast them.

3.1 Bargaining and posting

The two main approaches that have been taken to modeling wage determination in recent years are what we will call ex post wage-bargaining and ex ante wage-posting (though we briefly discuss others at the end of the section). In ex post wage-bargaining the wage is split after the worker and employer have been matched, according to some sharing rule, most commonly an asymmetric Nash bargain. In ex ante wage-posting the wage is set unilaterally by the employer before the worker and employer meet.

These two traditions have been used in very different ways. The bargaining models are the preferred models in macroeconomic applications (see Rogerson and Shimer, 2011) while microeconomic applications tend to use wage-posting8. But, what is often not very clear to students entering this area is why these differences in tradition have emerged and what are the consequences. Are these differences based on good reasons, bad reasons or no reasons at all? Here we try to provide an overview which, while simplistic, captures the most important differences.

Although the models used are almost always dynamic, the ideas can be captured in a very simple static model and that is what we do here. The simple static model derives from Hall and Lazear (1984) who discuss a wider set of wage-setting mechanisms than we do here. Assume that there are firms, which differ in their marginal productivity of labor, p. A firm is assumed to be able to employ only one worker.

In ex post wage-bargaining models, the wage in a match between a worker with leisure value b and a firm with productivity p is chosen to maximize an asymmetric Nash bargain:

![]() (9)

(9)

leading to a wage equation:

![]() (10)

(10)

where α can be thought of as the bargaining power of the worker, which is typically thought of as exogenous to the model. The match will be consummated whenever there is some surplus to be shared, i.e. whenever p ≥ b so that there is ex post efficiency. There will not necessarily be ex ante efficiency if worker or employer or both have to make investments ahead of a match, investments either in the probability of getting a match or in the size of rents when a match is made. For example, if α = 0 workers get no surplus from the employment relationship so would not invest any time in trying to find a job.

Now consider a wage-posting model in which employers set the wage before being matched with a worker. To derive the optimal wage in this case we need to make some assumption about the process by which workers and employers are matched—for the moment, assume that is random though alternatives are discussed below. And assume that workers differ in their value of leisure, b—denote the distribution function of this across workers by G(b).

If the firm sets a wage w, a worker will accept the offer if w > b, something that happens with probability G(w). So expected profits will be given by:

![]() (11)

(11)

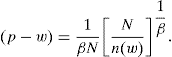

This leads to the following first-order condition for wages:

![]() (12)

(12)

where ε is the elasticity of the function G with respect to its argument and the notation used reflects the fact that this elasticity will typically be endogenous. Higher productivity firms offer higher wages. An important distinction from ex post wage-bargaining is that not all ex post surplus is exploited—some matches with positive surplus (i.e. with p > b) may not be consummated because b > w. In matches that are consummated the rents are split between employers and workers, so employers are unable to extract all surplus from workers even though employers can unilaterally set wages.

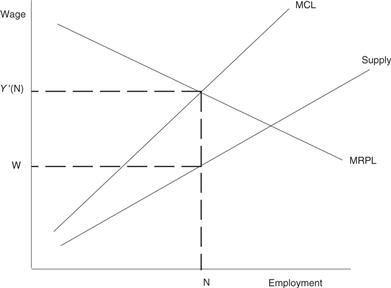

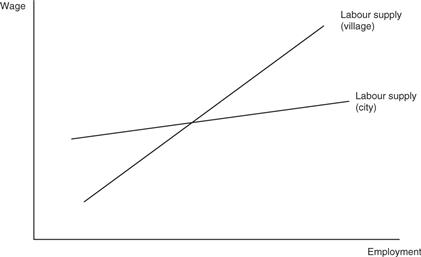

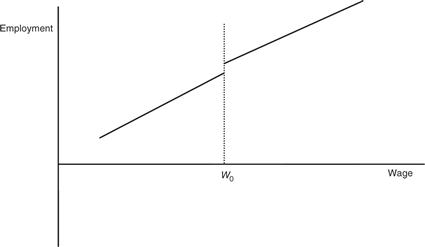

In this model G(w) can be thought of as the labor supply curve facing the firm, in which case can think of it as a standard model of monopsony in which the labor supply to a firm is not perfectly elastic and (12) as the standard formula for the optimal wage of a monopsonist. There is a simple and familiar graphical representation of the decision-making problem for the firm—see Fig. 1. In contrast, there is no such simple representation for the outcome of the ex post wage-bargaining model9.

One might think that the two wage Eqs (10) and (12) are very different. But they can easily be made to look more similar. Suppose that the supply of labor can be written as:

![]() (13)

(13)

where b0 is now to be interpreted, not as a specific worker’s reservation wage, but as the lowest wage any worker will work for. Then the wage equation in (11) can be written as:

![]() (14)

(14)

which is isomorphic to (9) with ![]() . In some sense, the bargaining power of workers in the wage-posting model is measured by the elasticity of the labor supply curve to the firm. However, note that the interpretation of the reservation wage in (10) and (14) is different—in (10) it is the individual worker’s reservation wage while in (14) it is the general level of reservation wages measured by the lowest in the market.

. In some sense, the bargaining power of workers in the wage-posting model is measured by the elasticity of the labor supply curve to the firm. However, note that the interpretation of the reservation wage in (10) and (14) is different—in (10) it is the individual worker’s reservation wage while in (14) it is the general level of reservation wages measured by the lowest in the market.

The assumption of random matching plays an important role in the nature of the wage-posting equilibrium so it is instructive to consider other models of the matching process. The main alternative to random matching is “directed search” (see, for example, Moen, 1997). Models of directed search typically assume that there is wage-posting but that all wage offers can be observed before workers decide on their applications.

Although models of directed search make the same assumption about the availability of information on wage offers as models of perfect competition (i.e. complete information), they do not assume that an application necessarily leads to a job, so there is typically some frictional unemployment in equilibrium caused by a coordination problem. So the expected utility of a worker applying to a particular firm is not just the wage, but needs to take account of the probability of getting a job. In the simplest model this expected utility must be equalized across jobs, giving the model a quasi-competitive feel, and it is perhaps then no surprise that the outcomes are efficient. The literature has evolved with different assumptions being made about the number of applications that can be made, what happens if workers get more than one job offer, what happens if the first worker offered a job does not want it (e.g. Albrecht et al., 2006; Galenianos and Kircher, 2009; Kircher, 2009). It would be helpful to have some general principles which help us understand the exact feature of these models that do and do not deliver efficiency.

3.2 The right model?

Rogerson et al. (2005, p. 984) conclude their survey of search models by writing that one of the unanswered questions is “what is the right model of wages?”, with the two models described above being the main contenders. If we wanted to choose between these two descriptions of the wage determination process, how would we do so? We might think about using theoretical or empirical arguments. As economists abhor unexploited surpluses, theory would seem to favor the ex post wage-bargaining models in which no match with positive surplus ever fails to be consummated10. One might expect that there would be renegotiation of the wage in a wage-posting model if p > b > w.

However, over a very long period of time, many economists have felt that this account is over-simplistic, that wages, for reasons that are not entirely understood, have some form of rigidity in them that prevents all surplus being extracted from the employment relationship. There are a number of possible reasons suggested for this. Hall and Lazear (1984) argue this is caused by informational imperfections while Ellingsen and Rosen (2003) argue that wage-posting represents a credible commitment not to negotiate wages with workers something that would cost resources and raise wages. There is also the feeling that workers care greatly about notions of fairness (e.g. see Mas, 2006) so that this makes it costly to vary wages for workers who see themselves as equals. There is also the point that if jobs were only ever destroyed when there was no surplus left to either side, there would be no useful distinction between quits and lay-offs, though most labor economists do think that distinction meaningful and workers losing their jobs are generally unhappy about it. The bottom line is that theory alone does not seem to resolve the argument about the “best” model of wage determination.

What about empirical evidence? In a recent paper Hall and Krueger (2008) use a survey to investigate the extent to which newly-hired workers felt the wage was a “take-it-or-leave-it” offer, as ex ante wage-posting models would suggest. All those who felt there was some scope for negotiation are regarded as being ex post wage-bargaining. They show that both institutions are common in the labor market, with negotiation being more prevalent. In low-skill labor markets wage-posting is more common than in high-skill labor markets, as perhaps intuition would suggest.

This direct attempt to get to the heart of the issue is interesting, informative and novel, but the classification is not without its problems. For example, some of those who report a non-negotiable wage may never have discovered that they had more ability to negotiate over the wage than the employer (successfully) gave them the impression there was. For example, Babcock and Laschever (2003) argue that women are less likely to negotiate wages than men and more likely to simply accept the first wage they are offered.

Similarly, there are potential problems with assuming that all those without stated ex ante wages represent cases of bargaining. For example, employers with all the bargaining power would like to act as a discriminating monopsonist tailoring their wage offer to the circumstances of the individual worker, not the simple monopsonist the wage-posting model assumes. Hall and Krueger (2008) are aware of this line of argument but argue it is not relevant because wage discrimination would result in all workers in the US being held to their reservation wage, a patently ridiculous claim. But, there is a big leap from saying some monopsonistic discrimination is practiced to saying it is done perfectly, so this argument is not completely compelling.

There is also the problem that the methodology used, while undoubtedly fascinating and insightful, primarily counts types of contract without looking at the economic consequences. For example, Lewis (1989, p. 149) describes how Salomon Brothers lost their most profitable bond-trader because of their refusal to break a company policy capping the salary they would pay. Undoubtedly, this contract should be described as individualistic wage-bargaining, but there were limits placed on that which resulted in some ex post surplus being lost as suggested by the wage-posting models.

One possible way of resolving these issues would be to look at outcomes. For example, ex post individualistic wage-bargaining would suggest, as from (10), that there would be considerable variation in wages within firms between workers with different reservation wages—see (10). On the other hand, ex ante wage-posting would suggest no wage variation within firms between workers with different reservation wages. Machin and Manning (2004) examine the structure of wages in a low-skill labor market, that of care workers in retirement homes. They find that, compared to all other characteristics of the workers, a much greater share of the total wage variation is between as opposed to within firms. Reservation wages are not observed directly, but we might expect to be correlated with those characteristics, so ex post wage-bargaining would predict correlations of wages with those variables11.

One could spend an enormous amount of time debating the “right” model of wage determination. But we will probably never be able to resolve it because the labor market is very heterogeneous, so that no one single model fits all, so the question of “what is the right model?” is ill-posed. In fact, it is the very existence of rents that gives the breathing-space in the determination of wages in which the observed multiplicity of institutions can survive. In a perfectly competitive market an employer would have no choice but to pay the market wage and to deviate from that, even slightly, leads to disaster.

It is also worth reflecting that, in many regards, wage-bargaining and wage-posting models are quite similar (e.g. they both imply that rents are split between worker and employer) so that it may not make very much difference which model one uses as a modeling device. The main substantive issue in which they differ is in whether one thinks that all ex post surplus is extracted. But, because even ex post efficiency does not mean ex ante efficiency, this may not be such a big difference in practice. However, this is not to say that the choice of model has had no consequences for labor economics because too many economists see the labor market only through the prism of the labor market model with which they are most familiar.

For example, as illustrated above, a wage-posting model naturally leads one to think in terms of the elasticity of the labor supply curve to an individual firm and that one can represent the wage decision using the familiar diagram of Fig. 1. It is easy to forge links with other parts of labor economics, so it is perhaps not surprising that this has often been the model of choice for microeconomic models of imperfect competition in the labor market. It is much more difficult to forge such links with an ex post bargaining model and the literature that uses such models sometimes seems to have developed in a parallel universe to more conventional labor economics and has concentrated on macroeconomic applications.

3.3 Other perspectives on wage determination

I have described the two most commonly found models of wage determination. But just as I have emphasized that one should not be thought as obviously “better” than the other, so one should not assume that these are the only possibles. Here we simply review some of the others that can be found in the literature. We make no attempt to be exhaustive (e.g. see Hall and Lazear, 1984, for a discussion of a range of possibilities we do not discuss here).

The simple model sketched above only has workers moving into jobs from non-employment because it is a one-period model. In reality, over half of new recruits are from other jobs (Manning, 2003a; Nagypal, 2005) so that one has to think about how wages are determined when a worker has a choice between two employers.

In models with ex-post wage-bargaining, on-the-job search is a bit tricky to incorporate into standard models because it is not clear how to model the outcome of bargaining when workers have a choice of more than one employer, and different papers have taken different approaches, e.g. Pissarides (1994) assumes that the fall-back position for workers with two potential employers is unemployment while Cahuc et al. (2006) propose that the marginal product at the lower productivity firm be the outside option. Shimer (2006) points out that the value function for employed workers is typically convex in the wage when there is the possibility of moving to a higher-wage job in the future, and derives another bargaining solution, albeit one with many equilibria.

In contrast, models based on wage-posting do not find it hard to incorporate on-the-job search, as they typically simply assume that the worker accepts the higher of the two wage offers. But, they do find it difficult to explain why the employer about to lose a worker does not seek to retain them by raising wages. A number of papers look at the institution of offer-matching (Postel-Vinay and Robin, 2002) in which the two employers engage in Bertrand competition for the worker. However, many have felt that offer-matching is not very pervasive in labor markets and have offered reasons for why this might be the case (see, for example, the discussion in Hall and Lazear, 1984).

4 Estimates of rent-splitting

The previous section reviewed theoretical models of the ways in which rents are divided between workers and employers—this section reviews empirical evidence on the same subject.

Section 2 reviewed some ways in which one might get some idea of the size of rents accruing to employers and workers. Because it produced estimates of the rents accruing to employer and worker, one could use these estimates to get some idea of how the rents are shared between employer and worker. But, because these estimates are assembled from a few, disparate sources of evidence, we have no study in which we could estimate both employer and worker rents in the same labor market, so that estimating how rents are shared by using an estimate of employer rents in one labor market and worker rents in another would not deliver credible evidence. So, in this section we review some other methodologies that can be thought of as seeking to estimate the way in which rents are split between worker and employer.

The part of the literature on imperfect competition in labor markets that has used ex post wage-bargaining as the model of wage determination and, consequently, uses an equation like (10) would tend to see rents being split according to the bargaining power of the workers. The studies that attempt to estimate a rent-sharing parameter are reviewed in Section 4.1. In contrast, models that are based on wage-posting have a monopsony perspective on the labor market and view the elasticity of the labor supply curve facing the employer as the key determinant of how rents are split. We review these ideas in Sections 4.2 and 4.3. Finally, we briefly review some studies that have sought to use estimates of the extent of frictions in the labor market to estimate how rents are divided.

4.1 Estimates of rent-sharing

In a bargaining framework, we are interested in how wages respond to changes in the surplus in the employment relationship, i.e. to measure something like (10). There is a small empirical literature that seeks to estimate the responsiveness of wages to measures of rents. These studies differ in the theoretical foundation for the estimated equation, the way in which the rent-sharing equation is measured and the empirical methodology used.

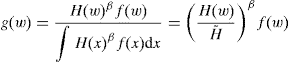

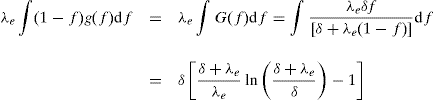

The Eq. (10) was derived from a model of bargaining between a worker and employer where the bargaining relationship covers only one worker. But, there are alternative ways of deriving a similar equation from other models. For example, Abowd and Lemieux (1993) assume that the firm consists of a potentially variable number of workers with a revenue function F(N), and that the firm bargains with a union with preferences N(w – b) over both wages and employment, i.e. we have an efficient bargaining model (McDonald and Solow, 1981). That is, wages and employment are chosen to maximize:

![]() (15)

(15)

One way of writing the first-order condition for wages in this maximization problem is:

![]() (16)

(16)

i.e. wages are a weighted average of revenue per worker and reservation wages with the weight on revenue per worker being α. The similarities between (16) and (10) should be apparent as F(N)/N is the average productivity of labor. In this model employment will be set so that:

![]() (17)

(17)

There are other models from which one can derive a similar-looking equation to (16), though we will not go into details here. For example, if one assumes that employment is chosen by the employer given the negotiated wage (what is sometimes called the right-to-manage or labor demand curve model—see, for example, Booth, 1995) or a more general set of ”union” preferences.

In all the specifications derived so far, it is a measure of revenue per worker or quasirents per worker put on the right-hand side. But, many studies write the wage equation in terms of profits per worker, i.e. take −αw from both sides of (16) and write it as:

![]() (18)

(18)

In all these cases it should be apparent that the outcome of rent per worker or profit per worker is potentially endogenous to wages, so that OLS estimation of these equations is likely to lead to biased estimates. Hence, some instrument is used, and the obvious instrument is something that affects the revenue function for the individual firm but does not affect the wider labor market (here measured by b). Although revenue function shifters sound very plausible, it is not clear that they are good instruments. For example if the revenue function is Cobb-Douglas (so the elasticity of revenue with respect to employment is a constant) then the marginal revenue product of labor is proportional to the average revenue product and the employment equation in (17) makes clear the marginal revenue product will not be affected by variables that affect the revenue function. In this case shifts in the revenue function result in rises in employment such that rents per worker and wages are unchanged12. The discussion in Abowd and Lemieux (1993, p. 987) is very good on this point. In cases close to this, instruments based on revenue function shifters will be weak. Many of the rent-sharing studies are from before the period when researchers were aware of the weak instrument problem (see Angrist and Pischke, 2008, for a discussion) and the instruments in some studies (e.g. Abowd and Lemieux, 1993) do not appear to be strong.

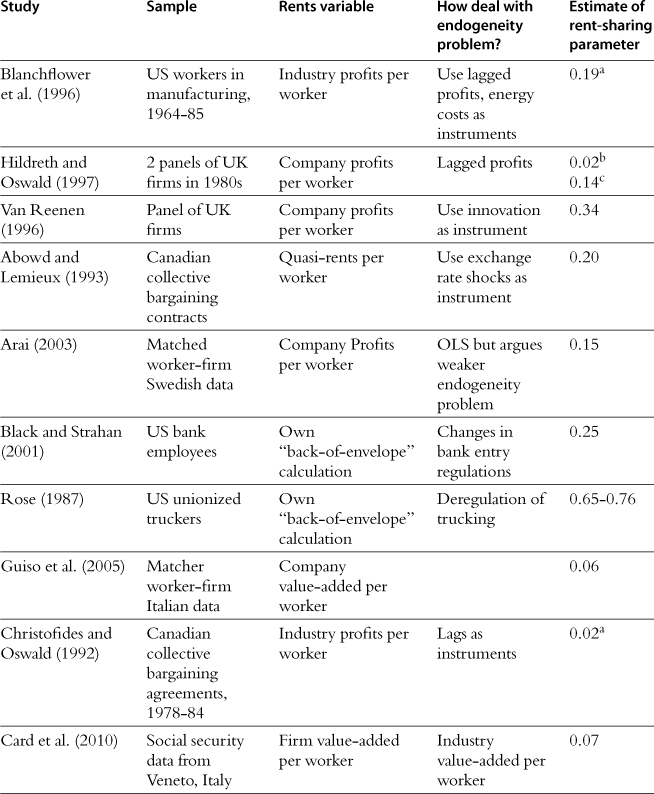

Some estimates of the rent-sharing parameter are shown in Table 4. In this table we have restricted attention to those that estimate an equation that is either in the form of (16) or (18) or can be readily transformed to it13. Table 4 briefly summarizes the data used in each study, the measure of rents or profits used, and the method (if any) used to deal with the endogeneity problem. In some studies the instruments are lags of various variables while others use exogenous shifts to demand, e.g. as caused by exchange rate movements. There are a couple of “case studies” of the impact of de-regulation in various industries.

Table 4

aThe equation is estimated with log earnings as dependent variable and rent-sharing parameter derived using reported figures for average profits per worker and a labor share in value-added of 75%.

bThis is computed using ratio of reported levels of earnings to profits per head in the data which is extremely low at 1.1. Using a ratio of 2 or 3 would raise these estimates considerably.

cThis is computed using ratio of reported levels of earnings to profits per head in the data which is high at 5.3. Using a ratio of 2 or 3 would lower these estimates considerably.

What one would ideally like to measure is the effect of a change in rents in a single firm on wages in that firm. It is not clear whether that is what is being estimated. For example, several studies in Table 4 use industry profits as a measure of rents. If labor has any industry-specific aspect to it then a positive shock to industry profits would be expected to raise the demand for labor in a competitive market and, hence, raise the general level of wages (represented by b in the model above)14. If this is important one would expect that the estimates reported in Table 4 are biased upwards. And the studies that use firm-level profits or rents but instrument by industry demand shifters are potentially vulnerable to the same criticism.

The final column in Table 4 presents estimates of the α implied by the estimates. Most of these studies do not report an estimate of α directly (e.g. the dependent variable is normally in logs whereas the theoretical idea is in levels) so a conversion has taken place based on other information provided or approximations. For example if the equation is specified with the log of wages on the left-hand side and the log of profits on the right-hand side so that the reported coefficient is an elasticity then one needs to multiply by the ratio of wages to profits per head to get the implied estimate of α. If, for example the share of labor in value-added is 75% then one needs to multiply the coefficient by 3, while if it is 66% one needs to multiply by 2. In addition there is a wide variation in the reported ratio of wages to profit per head in the data sets used in the studies summarized in Table 4 from a minimum of 1.1 to a maximum of 5.3. Unsurprisingly this can make a very large difference to the estimates of α and this is reflected in Table 4. In addition, the difficulty in computing the “true” measure of profits or rents may also lead to considerable variation in estimates.

There are a number of studies (Christofides and Oswald, 1992; one of the samples in Hildreth and Oswald, 1997) where α is estimate to be close to zero, but a number of other estimates are in the region 0.2-0.25. Studies from Continental European countries—the Italian and Swedish studies of Arai (2003), Guiso et al. (2005) and Card et al. (2010)— are markedly lower—this might be explained by the wage-setting institutions in those countries where one might expect the influence of firm-level factors to be less important than in the US (see the neglected Teulings and Hartog, 1998, for further elaboration of this point) though there are also some methodological differences from the other studies. And the study of Rose (1987) also looks an outlier with an estimate of α around 0.7. However, this estimate is derived using some back-of-the-envelope calculations and is for a very specific industry so may not be representative. It is worth remarking that all of these studies suggest that most rents accrue to employers, not workers while the direct estimates of the size of rents accruing to employer and workers in previous sections perhaps suggested the opposite. That is an issue that needs to be resolved.

The estimates of α discussed so far have all been derived from microeconomic studies. But the rent-splitting parameter also plays an important role in macroeconomic models of the labor market, and such studies often use a particular value. It has been common to assume the rent-splitting parameter is set to satisfy the Hosios condition for efficiency (often around 0.4), though no convincing reason for that is given, sometimes calibrated or estimated to help to explain some aspects of labor market data (and Hagedorn and Manovskii, 2008 suggest a value of 0.05 based on some of the studies reported in Table 4). A recent development (e.g. Pissarides, 2009; Elsby and Michaels, 2008) has been to argue that there is an important difference between the sensitivity of the wages of new hires and continuing workers to labor market conditions. The micro studies reviewed in Table 4 have not pursued this dimension.

Many of the studies summarized in Table 4 are of unionized firms, motivated by the idea that non-union firms are much less likely to have rent-sharing. Although a perspective that there are pervasive rents in the labor market would lead one to expect that even non-union workers get a share of the rents, one might expect unions to be institutions better-able to extract rents for workers, so that one would estimate a higher α in the union sector. But the few studies that distinguish between union and non-union sectors (e.g. Blanchflower et al., 1996, 199015) often find that, if anything, the estimate of α is larger in the non-union sector. However, this is what one might expect from a wageposting perspective, because a union setting a take-it-or-leave-it wage makes the labor supply to a firm more wage elastic (like the minimum wage) than that faced by a nonunion firm. Hence, one then predicts one would find a higher rent-sharing parameter in the non-union sector. This leads on to estimates of rent-sharing based on the elasticity of the labor supply curve to employers.

4.2 The elasticity of the labor supply curve to an individual employer

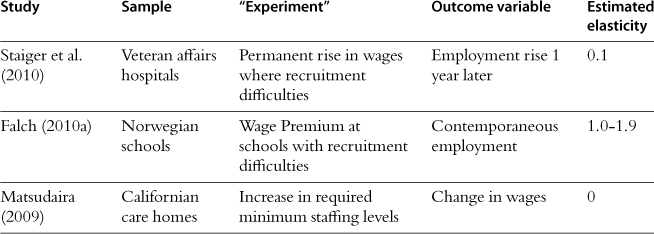

As the formula in (12) makes clear, a wage-posting model would suggest that it is the elasticity of the labor supply curve facing the employer that determines how rents are split between worker and employer. This section reviews estimates of that elasticity. An ideal experiment that one would like to run to estimate the elasticity of the labor supply curve to a single firm would be to randomly vary the wage paid by the single firm and observe what happens to employment. As yet, the literature does not have a study of such an experiment.

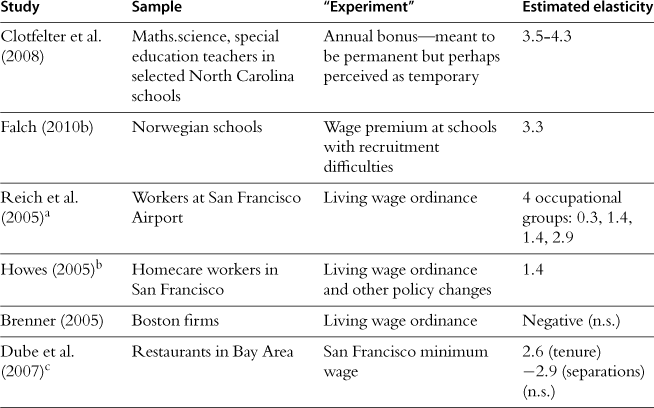

What we do have are a number of quasi-experiments where there have been wage rises in some firms—these are summarized in Table 5. Typically those experiments have been of public sector firms where there have been perceived to be labor shortages because wages have been set below prevailing market levels. So, they sound like the type of situation where one would expect to be tracing out the elasticity of a labor supply curve.

Staiger et al. (2010) examine the impact of a legislated rise in the wages paid at Veteran Affairs hospitals. They estimate the short-run elasticity in the labor supply to the firm to be very low (around 0.1), implying an enormous amount of monopsony power possessed by hospitals over their nurses. Falch (2010a) investigates the impact on the supply of teachers to individual schools in northern Norway in response to a policy experiment that selectively raised wages in some schools with past recruitment difficulties. He reports an elasticity in the supply of labor to individual firms in the region 1.0-1.9—higher than the Staiger et al study, but still very low.

Looking at these studies, one clearly comes away with the impression not that it is hard to find evidence of monopsony power but that the estimates are so enormous to be an embarrassment even for those who believe this is the right approach to labor markets. The wage elasticities are too large to be credible.

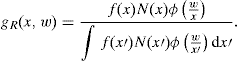

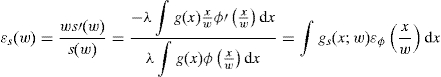

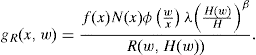

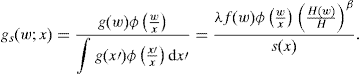

This means it makes sense to reflect on possible biases. There are a number of possibilities that come to mind. First, some of these studies only look at the response of employment to wage changes over a relatively small time horizon. As one would expect supply elasticities to be smaller in the short-run, these estimates are not reliable as estimates of the long-run elasticity. There is a simple back-of-the-envelope rule that can be used to link short-run and long-run elasticities. Boal and Ransom (1997) and Manning (2003a, chapter 2) show that if the following simple model is used for the supply of labor to a firm:

![]() (19)

(19)

where s(w) is the separation rate and R(w) is the recruitment rate, then there is the following relationship between the short-run and long-run elasticities:

![]() (20)

(20)

So one needs to divide the short-run elasticity by the quit rate to get an estimate of the long-run elasticity. If, for example, labor turnover rates are about 20% then one needs to multiply the estimates of short-run elasticities by 5 to get a better estimate of the long-run elasticity.

A second issue is whether the wage premia are expected to be temporary or permanent. If they are only temporary then one would not expect to see such a large supply response. In this regard, it is reasonable to think of the wage increases studied by Staiger et al. (2010) as permanent, those studied by Falch (2010a) as temporary. It is not clear whether an argument that the wage premia were viewed as only temporary are plausible as explanations of the low labor supply elasticities found.

Here, I suggest that there is another, as yet unrecognized, problem with these estimates of labor supply elasticities. The reason for believing this comes from thinking about estimates of the labor supply elasticities from an alternative experiment—force an employer to raise its employment level and watch what happens to the wages that they pay. This is what is analyzed by Matsudaira (2009) who analyzes the effect of a 1999 California law that required all licensed nursing homes to maintain a minimum number of hours of nurses per patient. This can be thought of as a mandated increase in the level of employment.

According the simplest models of monopsony in which there is a one-to-one relationship between wages and labor supply to the firm, the wage response to the mandated employment increase should give us an estimate of the inverse of the wage elasticity. If the studies of mandated wage increases cited above are correct and the labor supply elasticity is very small, we should see very large wage increases in response to mandated employment changes. This is especially true if the short-run elasticity is very low. In fact, Matsudaira finds that firms that were particularly affected by the mandated increased in employment did not raise their wages relative to other firms who were not affected. As a result, the labor supply to the employer appears very elastic, seemingly inconsistent with studies of mandated wage increases. It is possible that, as these are studies of different labor markets there is no apparent inconsistency but I would suggest that is not the most likely explanation and that the real explanation is a problem with the simple model of monopsony.

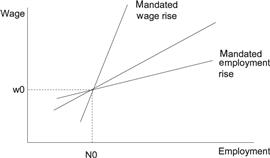

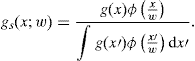

How can we reconcile these apparently conflicting findings? The problem with the simple-minded model of monopsony is that it assumes that the only way an employer can raise employment is by raising its wage. A moment’s reflection should persuade us that this is not very plausible. There are a number of possible reasons for this—I will concentrate on one in some detail and then mention others.