How Can Strategic Design of Work Tasks Improve an Organization?

Many of us like to describe what we do at work by telling others about our jobs. Most of the time, we do this without thinking about who decides what tasks should go with which job. Why does an organization have sales representatives who meet with potential customers, while other employees make the actual products? Why do automobile manufacturers organize workers into assembly lines? These questions involve work design, the process of assigning and coordinating work tasks. One key principle of work design is differentiation. Differentiation suggests that each worker should be assigned a set of similar tasks in order to specialize in doing certain things very well. Another key principle of work design is integration. Integration is concerned with coordinating the efforts of employees.1

Work design

The process of assigning and coordinating work tasks among employees.

Differentiation

The process of dividing work tasks so that employees perform specific pieces of the work process, which allows them to specialize.

Integration

The process of coordinating efforts so that employees work together.

Strategic work design uses both differentiation and integration to determine who does what. Good differentiation and integration of work helps organizations increase productivity and improve customer satisfaction.2 When work is designed strategically, employees' efforts are coordinated in a way that helps the organization achieve its competitive strategy.

One example of an organization with effective work design is W. L. Gore & Associates. Gore is perhaps best known for manufacturing apparel and camping products that are both water resistant and breathable. The company began in 1958 as a small shop in Bill Gore's basement. Since that time, it has grown into a multinational company with overall sales of $3 billion. Gore employs over 9,000 employees located throughout the world.3 In addition to manufacturing water-resistant fabric, known as Goretex, the company makes products for use in medicine, electronics, and industry.

The various products made by W. L. Gore are tied together by quality and innovation. People don't normally buy Gore products because they are inexpensive; they buy them because they are excellent products that meet their specific needs. Gore's official statement about its strategy is “Gore's products are designed to be the highest quality in their class and revolutionary in their effect.”4 W. L. Gore clearly competes with other organizations by pursuing a differentiation rather than a cost strategy.

In order to encourage innovation and quality, Gore allows workers a great deal of freedom in deciding what they will do. Workers at Gore don't usually have specific jobs. Nobody is given a job title, and employee business cards don't list specific positions. Employees are simply called associates. New employees negotiate with others to determine “commitments” that define their work role. Commitments take advantage of individual strengths and abilities and are different for every employee. Gore thus replaces top-down planning with a system that allows each employee freedom to determine the specific tasks that he or she will perform. This freedom encourages each individual to find a set of enjoyable tasks. Requiring negotiation with other employees ensures that the chosen tasks will indeed help the organization achieve its goals.5

Integration at W. L. Gore is achieved through dynamic teams. Many organizations use a hierarchical structure with bosses and clear channels of authority. In contrast, Gore is organized around a lattice structure, which allows employees to talk to anyone who might have information they need. Instead of having bosses plan and organize tasks, the efforts of individual workers at Gore are coordinated through teamwork.

Gore's practices have created a workplace where employees are highly satisfied. The company has been named one of the best places to work by numerous surveys conducted in a variety of countries including Germany, Italy, South Korea, Sweden, France, and the United Kingdom. And Gore was named for the sixteenth consecutive year as one of the U.S. “100 Best Companies to Work For” by Fortune magazine in 2013.6

Of course, not everyone is able to succeed in Gore's structure. Some people are uncomfortable without specific jobs that tell them what to do and leave Gore soon after they join. Positive peer pressure encourages people not to take advantage of the loosely organized system by not working hard.

Replacing formal planning and role assignment with a process in which roles evolve is beneficial for Gore. But would this evolutionary process be successful elsewhere? Few other organizations seem willing to try, suggesting that it may not fit their needs as well. In particular, the informal process at Gore is successful because it fits with the overall strategy of differentiation through innovation. Hiring creative employees and then letting them find ways to utilize their unique talents encourages new ideas. The process may not always be efficient, as the contributions of some workers may overlap with the contributions of others. However, small losses in efficiency are acceptable in return for the increased innovation that makes Gore products highly desirable to consumers. In essence, then, W. L. Gore & Associates is a successful company because it has developed an effective human resource system, which includes an untraditional approach for work design, to help carry out its competitive strategy of innovation.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

How Is Work Design Strategic?

The example of W. L. Gore shows that strategic work design can benefit an organization by assigning and coordinating tasks in ways that increase employee productivity. However, what it means to be productive may not be the same for all organizations. Instead of innovation and creativity, other organizations may benefit from speed and efficiency. The key to making work design strategic is therefore to align the methods used for assigning and coordinating tasks with overall HR strategy. Next, we consider two fundamental elements of work design—autonomy and interdependence—and then explain how these elements can be aligned with the HR strategies from Chapter 2.

DEVELOPING AUTONOMY

Take a moment and imagine you are observing the following experience. A family with four small children sits down in a restaurant. The waitress places a glass of water in front of each person. Fearing that the glasses will be broken, the parents ask the waitress to remove the glasses she placed in front of the children. “I'm sorry,” the waitress says, “I'll get in trouble if everyone at the table doesn't have a glass of water. It's our policy.” Even though the parents beg her to make an exception, the waitress follows standard procedure and leaves the glasses in front of the children. Sure enough, several minutes later, one of the glasses of water is pushed onto the floor and broken. Unlike W. L. Gore, the restaurant in this example gives employees little autonomy.

Autonomy concerns the extent to which individual workers are given the freedom and independence to plan and carry out work tasks.7 Greater autonomy provides two potential benefits to organizations. One benefit concerns information. In many cases, front-line workers are closer to customers and products and so they have information that a manager does not have.8 The workers can use this information to adapt quickly to change. Employees who are closer to products and customers are often able to make rapid changes if something in the production process shifts or if customers' needs vary. The “How Do We Know?” feature also describes a study that found greater autonomy to result in better coordination for teams, which in turn increased productivity.

Autonomy

The extent to which individual workers have freedom to determine how to complete work.

A second potential benefit of high autonomy is increased motivation. People with a greater sense of autonomy feel more responsibility for their work.9 More-autonomous employees are less likely to shirk their responsibilities. Employees who don't feel autonomy often fail to do their share of work tasks. People are also more likely to go beyond minimum expectations without extra pay when autonomy is high. High-level managers with greater autonomy in both the United States and Europe report greater job satisfaction and less chance of leaving their current employer.10 Managers working in a foreign country also adjust to the new environment better when they experience autonomy.11

High autonomy may not be desirable for all workers in all situations, however. High autonomy can create coordination problems. An employee with a great deal of freedom to change the work process might do something that changes processes and outcomes for other employees.12 Such changes are particularly troublesome when the work process is carefully planned in advance. For instance, high autonomy may not be good for workers in an automobile assembly plant. Production processes are carefully planned, and failure to follow rules and procedures might harm the entire assembly process. In contrast, autonomy can be helpful when tasks are complex and difficult to plan in advance. Workers with high autonomy can adapt to changing conditions and can do whatever is required to better meet the needs of customers.13

DEVELOPING INTERDEPENDENCE

Have you ever been assigned to write a group paper with other students? If so, how did your group complete the task? Did everyone write different sections of the paper? Did the group meet together and discuss the content of the paper? Did members of the group work in sequence so that individuals could add to what had already been done? These different processes for coordinating activities relate to interdependence.

Interdependence is the extent to which an individual's work actions and outcomes are influenced by other people. When interdependence is low, people work mostly by themselves. Each person completes his or her set of tasks without much help from or coordination with others. A good example is a group of sales representatives, each with an individual selling territory. At the other end of the spectrum is high interdependence, which occurs when people work together closely. Perhaps each team member completes a part of the task, and the work flows back and forth between team members. Each person adapts his or her inputs to the inputs of others. An example of high interdependence is found in a strategic planning team. Team members meet together and discuss issues to combine their knowledge and perceptions in order to arrive at shared decisions.

Interdependence

The extent to which a worker's actions affect and are affected by the actions of others.

Greater interdependence often corresponds with improved performance. When interdependence is high, people tend to feel greater responsibility for completing their tasks.14 People also report higher work satisfaction when their goals and tasks are interdependent with those of other workers.15 However, as with autonomy, the benefits of interdependence are not universal. Some organizations are most effective when there is little interdependence and employees work mostly by themselves. When employees do work together, the type of interdependence that is best for one organization is not necessarily the type that is best for another organization.

One common form of interdependence is sequential processing, which takes place when work tasks are organized in an assembly line. In a sequential process, tasks must be performed in a certain order. One person completes a certain set of tasks. The work then flows to the next person, who completes a different set of tasks. This flow continues until each member of the team has completed his or her work and the production of the good or service is complete. A computer manufacturing plant uses sequential processing when a number of workers sit at a table and assemble parts. One person places the memory board in the computer, another adds the hard drive, and someone else installs the software. The steps are completed in a specific order, and each of the workers has a clearly defined set of tasks to complete.

Sequential processing

Work organized around an assembly line such that the completed tasks of one employee feed directly into the tasks of another employee.

Another common form of interdependence, reciprocal processing, requires more interaction and coordination among workers. Reciprocal interactions occur when people work together in a team without carefully prescribed plans for completing work tasks. A group of workers is given a broad set of tasks, and the workers decide among themselves who will do what. The work process might be different each time the set of tasks is completed. In this situation, the specific actions of any worker depend a lot on the actions of other workers. Software engineers use reciprocal processing when they work as a team to create application programs. Because each program is different, the design process for one will be different from the design process for another. One person might have the expertise needed to take the lead role for one program, and another person might be the best leader for designing a different program. Someone in the team might make a suggestion that helps other team members think of new ideas. Team members work together, and the value of each engineer's contribution depends on the contributions of others.

Reciprocal processing

Work organized around teams such that workers constantly adjust to the task inputs of others.

The best type of interdependence depends on the work situation. Individuals and teams tend to benefit from sequential processes when work activities can be broken into small tasks that do not change. These tasks are often physical. Reciprocal processes tend to be optimal when activities are complex and require mental rather than physical inputs.16

LINKING AUTONOMY AND INTERDEPENDENCE TO HR STRATEGY

Figure 4.1 shows how differences in autonomy and interdependence can be linked to HR strategy. Organizations using cost HR strategies—either Bargain Laborer or Loyal Soldier—focus on efficiency. Efficiency is often created by combining low autonomy and sequential processing.17 With cost strategies, one objective is to standardize jobs so that employees can quickly learn a set of relatively easy tasks. A cook at a fast-food restaurant, for example, receives an order and follows clearly defined rules to cook the food, which is then delivered to someone who gives it to the customer. Another objective with cost strategies is to provide a way for each worker to become very skilled and efficient at performing certain tasks. Doing something over and over helps workers learn how to eliminate errors. Scientific studies are done to find ways to perform tasks more quickly, and everyone is required to follow best practices. Sequential processes and low autonomy thus correspond with improved performance when processes are simple and require mostly physical inputs. Managers overseeing this type of work are able to determine the best methods for accomplishing tasks. Activities are completed most quickly when each person performs a specific set of tasks that are coordinated by managers.

Figure 4.1 Strategic Framework for Work Design.

Organizations that use differentiation HR strategies—either Committed Expert or Free Agent—focus on innovation. High autonomy and reciprocal processes encourage creativity. With differentiation, the objective is to create new products and services that are better than those offered by competitors. People within the organization are more likely to meet this objective when they are free to try new approaches. Giving workers the freedom to experiment with new ideas helps companies such as W. L. Gore come up with new products. In addition, the close interaction between workers using reciprocal processes allows them to help each other and learn new things.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

How Are Employee Jobs Determined?

We wouldn't generally expect all the employees in an organization to perform the same tasks. Employees specialize in certain tasks, and people adopt specific roles. These tasks and roles are usually summarized in terms of jobs. A job is a collection of tasks that a person performs at work. The idea of being employed in a job is so common that many people think in terms of jobs when they describe themselves to others. But how are jobs defined? Why are some tasks grouped into a certain job while other tasks are grouped into a different job?

Job

A collection of tasks that define the work duties of an employee.

THE JOB ANALYSIS PROCESS

Job analysis is the process of systematically collecting information about work tasks. The process involves obtaining information from experts to determine the tasks that workers must perform, the tools and equipment they need to perform the tasks, and the conditions in which they are required to work. For instance, a job analysis of the work a student does might bring together a panel of experienced students and faculty. This panel would develop a list of the tasks that students commonly perform. Accompanying the list might be a description of typical tools, such as computers and textbooks. The analysis would also describe the conditions in which students work, such as lecture halls and study groups.

Job analysis

The process of systematically collecting information about the tasks that workers perform.

Job analysis is important because it helps clarify what is expected of workers. In the context of human resource management, knowing what tasks need to be completed helps managers select people with appropriate knowledge and skills. Understanding job tasks also provides important information for planning training programs. In addition, being able to compare the tasks of different workers helps guide decisions about pay. Finally, careful job analysis helps ensure that human resource practices comply with legal guidelines. In fact, good job analysis is often seen as a first step to appropriately recruiting, hiring, training, and compensating workers. A good example of a company that benefits from incorporating effective job analysis procedures is Purolator, which is featured in the “Building Strength Through HR” feature.

Figure 4.2 Phases of Job Analysis. Source: Information from Robert D. Gatewood and Hubert S. Field, Human Resource Selection, 5th ed. (Cincinnati, OH: South-Western, 2001).

The steps in the job analysis process, as shown in Figure 4.2, are getting organized, choosing jobs, reviewing knowledge, selecting job agents, collecting job information, creating job descriptions, and creating job specifications.18

Step 1. Getting Organized

An important first step is planning. Careful plans describing needed resources, such as staff support and computer assets, can help ensure success. During the organizing phase, it is also necessary to make sure that key decision makers support analysis plans. No matter how carefully procedures are planned, problems will arise, and top-management support will be necessary to make sure that the analysis proceeds successfully.

Step 2. Choosing Jobs

Of course, the goal in any organization is to analyze all jobs, but constraints on budgets and staff time often make it necessary to choose only some of these jobs. As you might expect, high priority should be given to jobs that are important to the success of the organization. Particular emphasis should be placed on jobs in which large numbers of people are employed. Focusing analysis on jobs that are both important and widely held ensures that efforts will be concentrated in areas where improvement can have its largest impact on making the organization successful.

Step 3. Reviewing Knowledge

The next step, reviewing knowledge, involves learning what is already known about similar jobs in other organizations. One important source of information is the Occupational Information Network, which was developed by the U.S. Department of Labor. The network, called O*Net, is online at http://online.onetcenter.org. The online database contains information for over a thousand occupations. A visitor to the website simply types in a common job—or occupational—title and is presented with a list of tasks that are normally associated with that position, along with other information. Although developed in the United States, O*Net data have been shown to be applicable in other countries such as New Zealand and China.19 Other sources of knowledge for job analysts include studies published in research journals such as Personnel Psychology and Journal of Applied Psychology. The information in these existing sources is not a substitute for a careful analysis but does provide a good starting point for learning about jobs.

Occupational Information Network

An online source of information about jobs and careers.

Step 4. Selecting Job Agents

Job agents are the people who provide the job information. In many cases, the best people to provide this information are job incumbents—the people currently doing the job. These employees are very familiar with day-to-day tasks. But one potential problem with using current employees is that they may emphasize what is actually done rather than what should be done. Another source of information is supervisors. Supervisors may not be as familiar with the details of the job, but they can often provide clarification about the tasks that they would like to see done. A third source of information is professionally trained analysts who make careers out of studying jobs. Although such specialists can provide an outside perspective, they may not be as familiar with how things are done in a particular organization.

A number of studies have examined differences in job agents. Information provided by job incumbents who are experienced is different from the information provided by incumbents who recently started the job.20 In addition, differences have been found for ratings from men and women,21 as well as for ratings from minority and nonminority incumbents.22 Some differences have also been reported between high- and low-performing employees.23 Given these differences, it is important that the characteristics of the sample of people who provide information for a job analysis be representative of the characteristics of people who will actually do the job.

Step 5. Collecting Job Information

The next step is to actually collect information about the job. A common method for collecting information is the job analysis interview, a face-to-face interaction in which a trained interviewer asks job agents about their duties and responsibilities. Agents can be interviewed individually or in groups. In either case, the interview should be structured so that the same questions are asked of everyone. Job analysis interviews can be useful for learning unique aspects of a particular job. Interviews can, however, be time consuming and costly.

Job analysis interview

Face-to-face meeting with the purpose of learning about a worker's duties and responsibilities.

A second common method for collecting information is the job analysis questionnaire. Here, agents respond to written questions about the tasks they perform on the job. One type of questionnaire is an off-the-shelf instrument that has been developed to provide information about numerous different jobs. Another type is a tailored questionnaire developed just to obtain information about a specific job in a specific organization. An advantage of job analysis questionnaires is that they are relatively inexpensive; a disadvantage is that they may only provide very general information.

Job analysis questionnaire

A series of written questions that seeks information about a worker's duties and responsibilities.

A third common method is observation. Job analysis observation requires job analysts to watch people as they work and to keep notes about the tasks being performed. This method can provide excellent information about jobs involving frequently repeated tasks. However, observation is difficult for jobs where tasks either are mental or are not done frequently enough to be observed by an outsider.

Job analysis observation

The process of watching workers perform tasks to learn about duties and responsibilities.

Given the different strengths and weaknesses of analysis techniques, the best advice is often to use a combination of techniques. Job analysis questionnaires can serve as relatively inexpensive tools to obtain broad information. This information can be supplemented by interviews and observations. The overall goal of this step is to obtain as much information as possible about the work tasks. We will look more closely at some specific job analysis methods in the next section.

Step 6. Creating Job Descriptions

Next, analysts use the job analysis information to create a job description. A job description is a series of task statements that describes what is to be done by people performing a job. This description focuses on duties and responsibilities and usually consists of a list of actions that employees perform in the job being described. An example of a job description for the job of home health aide is shown in Table 4.1.

Job description

Task statements that define the work tasks to be done by someone in a particular position.

Step 7. Creating Job Specifications

The final step uses job analysis information to create job specifications. Job specifications identify the knowledge, skills, and abilities that workers need in order to perform the tasks listed in the job description. Of course, job specifications are different from the job description. Job descriptions focus more on what is done, whereas job specifications focus on who is most likely to be able to perform the tasks successfully. An example of job specifications for the position of home health aide is shown in Table 4.2.

Job specifications

Listing of the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed to perform the tasks described in a job description.

Source: Information from the Occupational Information Network O*Net OnLine, http://online.onetcenter.org/.

SPECIFIC METHODS OF COLLECTING JOB ANALYSIS INFORMATION

Let's look more closely at how information is gathered in Step 5 of the job analysis process. Many methods have been developed for collecting job analysis information. In this section, we examine three representative methods: the task analysis inventory, the critical-incidents technique, and the Position Analysis Questionnaire. The first two are broad techniques that provide a general methodology for analyzing jobs. Although several different consulting firms market applications of these techniques, the principles used are not unique to these firms. A number of common principles underlie specific practices, and we describe these principles rather than the specific practices of a particular consulting firm. The third tool we discuss, the Position Analysis Questionnaire, is a bit different; it is a specific analysis tool that is marketed by a single firm.

Task Analysis Inventory

The task analysis inventory asks job agents to provide ratings concerning a large number of tasks. Most analyses require responses for at least 100 different task statements. These task statements usually begin with an action verb that describes a specific activity—for example, “explains company policies to newly hired workers” and “analyzes data to determine the cost of hiring each new employee.”

Task analysis inventory

A method of job analysis in which job agents rate the frequency and importance of tasks associated with a specific set of work duties.

Source: Information from the Occupational Information Network O*Net OnLine, http://online.onetcenter.org/.

Most task analyses require job agents to provide at least two ratings for each task statement; one rating is for frequency or time spent, and the other is for importance. Ratings for frequency of performing the task range from “never performed” to “performed most of the time.” Ratings might also be made for time spent on the task. However, ratings of frequency and time spent essentially measure the same thing.24 Ratings for task importance usually range from “not important” to “extremely important.”25

Task inventories yield information that is consistent across time, meaning that ratings provided by a specific rater at one point in time are similar to ratings obtained from the same rater at a different point in time.26 Different groups of raters do, however, sometimes provide different results. The task analysis inventory thus seems to work best when job incumbents who are relatively new to the position provide ratings of frequency and importance.27

A task analysis inventory is fairly specific to a particular category of jobs. Thus, an analysis that provides insight into the job of grocery store clerk will provide little information about the job of taxi driver. However, the inventory does provide a good deal of detailed information about the job being studied.

Critical-Incidents Technique

The critical-incidents technique identifies good and bad on-the-job behaviors. Job agents are asked to generate a number of statements that describe behaviors they consider particularly helpful or harmful for accomplishing work. Each statement includes a description of the situation and the actions that determined whether the outcome was desirable or undesirable.28 Statements are then analyzed to identify common themes.

Critical-incidents technique

A method of job analysis in which job agents identify instances of effective and ineffective behavior exhibited by people in a specific position.

Results from an analysis using the critical-incidents technique are shown in Table 4.3. The analysis provides information about nurse behavior that encourages or discourages patients to participate in their own care while hospitalized. In the study, 17 patients were interviewed and asked to describe specific incidents that encouraged or discouraged them from participating in their own care. Interviewers asked additional questions to understand the circumstances leading to the event, nurse actions, and patient responses. Results illustrated that patients participate more when nurses regard them as a person, share information, and acknowledge the patient as competent. Patients withdraw from participating when they feel abandoned, belittled, or ignored. These responses were linked to the nurse behaviors shown in Table 4.3, clarifying specific actions that nurses can take to increase patient participation.29

Position Analysis Questionnaire

The Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ) is a structured questionnaire that assesses the work behaviors required for a job.30 This questionnaire collects information not about tasks or duties but rather about the characteristics people must have in order to do the job well. In essence, the PAQ skips Step 6 in the job analysis process and goes right to Step 7.

Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ)

A method of job analysis that uses a structured questionnaire to learn about work activities.

The PAQ includes 187 items that relate to job activities or the work environment. These items assess characteristics along six dimensions:

- Information input—where and how a worker obtains needed information.

- Mental processes—reasoning and decision-making activities.

- Work output—physical actions required for the job, as well as tools or devices used.

Source: Information adapted from Inga E. Larson, Monica J.M. Sahlsten, Kerstin Segesten, and Kaety A.E. Plos, “Patient Perceptions of Nurses' Behavior That Influence Patient Participation in Nursing Care: A Critical Incidents Study,” Nursing Research and Practice, Article ID 534060 (2011).

- Relationships with other persons—the interactions and social connections that a worker forms with others.

- Job context—the physical and social surroundings where work activities are performed.

- Other job characteristics—activities, conditions, or characteristics that are important but not contained in the other five dimensions.

Questions on the PAQ are rated on scales according to what is being measured. One scale, for example, is based on extent of use and ranges from “very infrequently” to “very substantial.” Another is based on importance to the job and ranges from “very minor” to “extreme.” A few items are simply rated as “does not apply” or “does apply.”

An advantage of the PAQ is its usefulness across many different jobs. Since the information concerns worker characteristics rather than tasks, results can be compared across jobs that are quite different. For instance, PAQ results might be used to determine whether two very different jobs require similar inputs. The degree of similarity will tell management whether people doing these jobs should be paid the same amount. A disadvantage of the PAQ is its lack of task information, which limits its usefulness for creating job descriptions or guiding performance appraisal practices. The PAQ is nevertheless one of the most commonly used methods of job analysis.

HOW IS JOB DESCRIPTION INFORMATION MADE USEFUL?

A few methods, like the PAQ, develop descriptions of worker characteristics rather than tasks and duties. However, the result of most job analysis techniques is a list of duties. As shown in Figure 4.3, job descriptions focus on tasks and duties, whereas job specifications focus on characteristics of people. Information in job descriptions must therefore be translated into job specifications, which are required for purposes such as employee selection. After all, just knowing what employees do in a certain job isn't very helpful for determining the type of person to hire. The people doing the hiring also need to know what characteristics to look for in job applicants.

Translation into job specifications is usually done by job agents. To make good translations, job agents must be highly familiar with the job and what it takes to perform it well. They look at the list of tasks and make judgments about the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed to complete the tasks. The characteristics are incorporated into the job specifications. For instance, job agents for the position of student might be asked to make judgments about the skills needed to take notes in class. The list of skills would include some obvious characteristics, such as ability to hear and write. Other characteristics might be less obvious but more helpful for identifying people who do the tasks well—for example, the ability to simultaneously listen and write, a knowledge of note-organizing techniques, and skill in asking follow-up questions. Good job specifications thus focus attention on knowledge, skills, and abilities that separate high- and low-performing workers.

Figure 4.3 Comparing Job Descriptions and Job Specifications.

Job specifications provide information that serves as a foundation for a number of other human resource practices. Managers can use the list of worker characteristics as a “shopping list” when they begin identifying the type of workers they want to hire. Carefully prepared job specifications also guide selection practices so that appropriate tests can be found to identify who actually has the desirable characteristics. In addition, areas in which current employees lack skills necessary for promotion can be established as training priorities.

These priorities serve as important information for designing the training programs discussed in Chapters 9 and 10. Also, as explained in Chapters 11 and 12, knowing the employee characteristics associated with high task performance can also provide important guidance for compensation decisions. People who have more desirable characteristics will likely expect to receive higher pay, particularly if few others have the same characteristics.

JOB ANALYSIS AND LEGAL ISSUES

The process of job analysis is a starting point for many good human resource practices. Practices grounded in good analysis are most likely to result in good decisions about how to hire, evaluate, and pay employees. Legal considerations are another important reason for good job analysis.

A number of court decisions have confirmed the importance of using good job analysis procedures.31 When an organization makes hiring or promotion decisions that have discriminatory effects, the organization can defend itself successfully by showing that it based its decisions on solid analyses of the jobs involved. In contrast, such decisions appear arbitrary and can be judged illegal if the organization has not used good job analysis procedures. Some procedures that have been identified as critical for conducting a legally defensible job analysis are listed in Table 4.4. Following these procedures helps ensure that an organization thoroughly analyzes jobs and uses the information to develop fair hiring and compensation procedures.32

Source: Information from Duane E. Thompson and Toni A. Thompson, “Court Standards for Job Analysis in Test Validation,” Personnel Psychology 35 (1982): 865–874.

Job analysis results can also help many organizations determine whether they are complying with requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which we discussed in Chapter 3. ADA guidelines make an important distinction between essential and nonessential tasks. For a disabled employee to be qualified for a position, he or she must be able to perform all essential tasks (with reasonable accommodations). The employee is not, however, required to be able to perform non-essential tasks. For example, an essential task for a landscape worker might be to identify and remove weeds. A nonessential task might be communicating verbally with other employees. In this case, an applicant with a speech disability might be seen as qualified for the job. The key to qualification is the extent to which verbal communication is necessary. If the job description does not identify verbal communication as an essential task for landscape workers, then the organization cannot appropriately refuse to hire someone who cannot speak.

COMPETENCY MODELING

The process of job analysis has been criticized in recent years, primarily because work today is less structured around specific jobs than it once was.33 Work activities are more knowledge based. People increasingly work in teams. Task activities are more fluid and are determined through ongoing negotiation among workers.34 By the time human resource practices based on job analysis can be designed and carried out, the task activities may have changed.35 Work behavior in modern organizations is thus not easily described.

A recent development designed to adapt to the changing needs of modern organizations is competency modeling, which describes jobs in terms of competencies—characteristics and capabilities people need in order to succeed at work. Competencies include knowledge, skills, and abilities, but they also seek to capture such things as motivation, values, and interests. Competencies thus include both “can-do” and “will-do” characteristics of people.36 One area of difference between competency modeling and traditional job analysis is that competency modeling tends to link a broader set of characteristics to work success.

Competency modeling

An alternative to traditional job analysis that focuses on a broader set of characteristics that workers need to effectively perform job duties.

Competencies

Characteristics and capabilities that people need to succeed in work assignments.

Typical steps for competency modeling are shown in Figure 4.4.37 Part of data collection is an assessment of competitive strategy. Consistent with the strategic focus of this textbook, competency modeling seeks to develop links between work activities and organizational strategy. The competency approach tailors solutions to purposes and uses. An analysis that will be used for compensation decisions may be different from an analysis that will be used for determining the type of job candidate to recruit. Competencies also tend to be somewhat broader and less specifically defined than the activities assessed in job analysis. Typical competencies might include skill in presenting speeches, ability to follow through on commitments, proficiency in analyzing financial information, and willingness to persist when work becomes difficult. Competencies can be rated in terms of things like current importance, future importance, and frequency.

You can see that job analysis and competency modeling differ in some important respects. Competency modeling is much more likely than job analysis to link work analysis procedures and outcomes to business goals and strategies. However, in most cases, the methods used in competency modeling are seen as being less scientific.38 Competency modeling procedures are often not documented as clearly as job analysis procedures and may be less rigorous.

Figure 4.4 Steps in Competency Modeling. Source: Information from Antoinette D. Lucia and Richard D. Lepsinger, The Art and Science of Competency Models: Pinpointing Critical Success Factors in Organizations (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer, 1999).

Comparing the strengths and weaknesses of traditional job analysis and competency modeling, however, obscures the important contribution that is possible by combining the best elements of the two practices. Competency modeling incorporates strategic issues and allows for a broader range of characteristics. From the other side, traditional job analysis provides excellent techniques for scientifically analyzing work activities. Combining the broader, more strategic approach of competency modeling with scientific methods should yield superior results. Indeed, a series of research studies concluded that a combined approach is better than either approach alone.39 Best practices thus incorporate job analysis along with future-oriented job requirements and organizational goals to analyze competencies. Information is then presented in the common language of organizations, including diagrams and pictures. A final key is that competency information be strategically integrated to ensure that HR practices associated with hiring, performance appraisal, and compensation work in unison to select and motivate employees through consistent policies.40

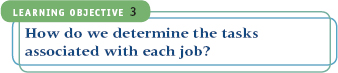

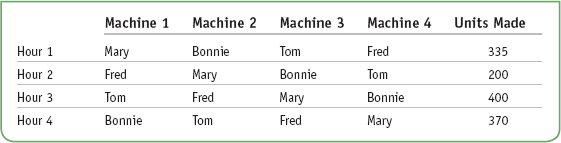

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

How Do We Determine the Tasks Associated with Each Job?

Next time you visit a sandwich shop, take a moment to observe the work process. Does the same person who takes your order also fix the sandwich and then take your payment? Or does one person take your order, another fix the sandwich, and still another accept your payment? Some shops use a process in which a single employee serves each customer. In other shops, each employee specializes in only one part of the service. Job analysis procedures would find that each person working in the first shop must perform a lot of different tasks, whereas employees in the second shop perform a limited set of tasks over and over. Job analysis thus provides information about who does what, but it doesn't tell us anything about how the tasks were combined into jobs in the first place. The process of job design focuses on determining what tasks will be grouped together to form employee jobs. This process of job design is critical, as nearly half of the differences in worker attitudes and behavior can be traced to factors such as task design, social interactions, and work conditions.41

Job design

The process of deciding what tasks will be grouped together to define the duties of someone in a particular work position.

Job design is important when companies are first created and when existing companies open new plants or stores. However, the principles of job design are also important for existing companies that are looking to improve. Many companies use job redesign to reorganize tasks so that jobs are changed. Job redesign often increases the sense of control for workers.42 Indeed, job redesign that empowers employees is particularly effective for improving performance when managers have not been providing employees with feedback and information.43 The “Building Strength Through HR” feature describes how such a redesign benefitted a large teaching hospital in England.

Job redesign

The process of reassessing task groupings to create new sets of duties that workers in particular positions are required to do.

Problems arise when work tasks are not organized well. Earlier in this chapter, we discussed the concepts of differentiation and integration. Differentiation allows people to specialize in specific tasks, while integration coordinates actions among employees. Employees feel isolated when there is too much differentiation. Many also feel frustrated when they are unable to easily integrate their actions with the actions of other workers. A major objective of work design is thus to differentiate and integrate work tasks in ways that not only make employees more productive but also increase their satisfaction.

Work tasks that are not properly differentiated and integrated deplete employee mental and physical capacity and create fatigue and burnout.44 Burned out employees are more likely to leave the organization.45 Workers with unclear roles, and those who experience constraints such as bad equipment and supplies, are particularly at risk.46 These exhausted employees have decreased motivation and are less likely to help other workers voluntarily.47 They are also more prone to abuse alcohol and drugs.48 Some burnout can be resolved by making sure that people have jobs that fit their capabilities and by treating employees fairly.49 Workers experience less exhaustion when they receive social support from coworkers.50 People also seem to be better able to cope with exhaustion when they believe that they are performing at a high level.51 Taking a vacation can also reduce burnout.52

Job design and redesign specialists have adopted a number of approaches for attacking the problem of grouping tasks in ways that make jobs more productive and satisfying. The main objective of any work design method is to separate and combine work tasks in ways that make the most sense. What makes sense depends on the overall objective of the organization and is driven by strategic choices. In this section, we describe four general approaches to grouping work tasks: mechanistic, motivational, perceptual, and biological. As you will see, many of the differences in these approaches can be traced to differences among the research areas and disciplines where they originated.

MECHANISTIC APPROACH

In a mechanistic approach, engineers apply concepts from science and mathematics to design efficient methods for creating goods and services. In particular, industrial engineers approach job design from the perspective of creating an efficient machine that transforms labor inputs into goods and services. They use principles of scientific management to create jobs that eliminate wasted effort so that organizations can produce goods and services quickly.53 In creating these jobs, they often use analyses designed to find the work methods that take the least time. For example, in a typical analysis, an observer might use a stopwatch to time different methods for moving boxes from one spot to another. Emphasis is placed on finding the fastest way to lift and carry boxes. The job is then designed so that each employee learns and uses the fastest method.

Scientific management

A set of management principles that focus on efficiency and standardization of processes.

The basic goal of the mechanistic approach is to simplify work tasks as much as possible. Tasks are automated. Each job is highly specialized, and to the degree possible, tasks are straightforward. Workers focus on carrying out only one task at a time, and a small set of tasks is completed over and over.54 The mechanistic approach thus tends to reduce worker autonomy and create sequential processing. Having workers specialize and complete simplified tasks has indeed been linked to greater efficiency.55 Organizations pursuing either Loyal Soldier or Bargain Laborer HR strategies can thus benefit from job design practices that emphasize the mechanistic approach.

United Parcel Service (UPS) uses the mechanistic approach as part of a Loyal Soldier HR strategy. UPS needs to move packages as efficiently as possible. People who work as sorters in package warehouses use carefully planned methods for carrying packages. From time to time, specialists observe sorters and make sure that they are following prescribed practices. Truck drivers at UPS also follow specific procedures for tasks such as planning delivery routes and starting trucks. The entire process is very much like an assembly line. The most efficient methods for completing tasks are determined and then taught to everyone. This standardization creates efficiency, which helps reduce the cost of moving packages and, in turn, creates value for customers.

MOTIVATIONAL APPROACH

Work design can also be approached from the perspective of psychologists. Instead of seeking to build a machine, psychologists study human minds and behavior. A specific branch of study called organizational psychology emphasizes designing work to fulfill the needs of workers. This motivational approach is aimed at increasing employees' enjoyment of their work and thus increasing their effort. For example, people given the goal of developing a marketing plan for a cell phone manufacturer might be given a large number of different tasks that allow them to exercise creativity. Jobs are designed not simply to get work done as quickly as possible but also to provide workers with tasks they find meaningful and enjoyable.56 The “How Do We Know?” feature describes a study that illustrates the benefits of making work tasks meaningful and significant.

Unlike the mechanistic approach, the motivational approach seeks to design work so that it is complex and challenging. One popular model of motivational job design is the job characteristics model, which focuses on building intrinsic motivation.57 Intrinsic motivation exists when employees do work because they enjoy it, not necessarily because they receive pay. According to the job characteristics model, people are intrinsically motivated when they perceive their work to have three characteristics:

Job characteristics model

A form of motivational job design that focuses on creating work that employees enjoy doing.

- Meaningfulness. People see work as meaningful when they are able to use many different skills, when they can see that their inputs lead to the completion of a specific service or product, and when they see their tasks as having an important impact on other people.

- Responsibility. People feel personal responsibility for work outcomes when they have autonomy, which comes from the freedom to make decisions.

- Knowledge of the results. Knowledge of the results of work activities comes from receiving feedback in the form of information about how effectively the work is being done.

People who feel intrinsic motivation exhibit higher creativity.58 This suggests that the motivational approach to job design is particularly useful for organizations pursuing Committed Expert or Free Agent HR strategies. Organizations with these strategies can benefit from the greater intrinsic motivation and creativity that comes from experiencing meaningfulness, responsibility, and knowledge of results. Designing work around motivational principles also increases worker satisfaction and enables organizations to retain quality employees.59 In particular, providing workers with high autonomy provides a means for organizations pursuing differentiation strategies to maximize the benefit of employing highly educated and trained workers who often know more than managers.

W. L. Gore & Associates, which you read about earlier in the chapter, offers a good example of a company that uses the motivational approach as part of a differentiation strategy. Workers are given a great deal of autonomy to determine work tasks. Based on their interests and capabilities, they enter agreements that allow them to complete work tasks that they perceive as important. They also have the freedom to engage in a variety of activities. Decreases in efficiency that come from duplication of effort are balanced by high levels of creativity. Intrinsically motivated workers create unique products.

PERCEPTUAL APPROACH

Some psychologists take a perceptual, rather than a motivational, approach. Job designers using this approach group tasks together in ways that help workers to process information better. These experts look at things such as how easily displays and gauges can be read and understood. They design written materials and instructions to be easy to read and interpret. They also examine how much information must be remembered and how much complex problem solving is required.

The basic objective of the perceptual approach is to simplify mental demands on workers and thereby decrease errors. Safety and prevention of accidents are critical. Given its emphasis on simplicity, the perceptual approach to job design usually results in work characterized by sequential processing and low autonomy. Thus, it is most commonly found in organizations pursuing either Loyal Soldier or Bargain Laborer HR strategies. For instance, an oil refinery could use perceptual principles to ensure that gauges and meters are designed to present information clearly so that plant workers do not make mistakes that result in accidents.

BIOLOGICAL APPROACH

People with backgrounds in biology and physiology also provide inputs into work design. They study issues associated with health and physical functioning. Physiologists particularly emphasize the physical stresses and demands placed on workers. Yet physical demands often combine with psychological stress to cause injuries.60

The biological approach is sometimes associated with ergonomics, which concerns methods of designing work to prevent physical injury. Task demands are assessed in terms of strength, endurance, and stress put on joints. Work processes are then designed to eliminate movements that can lead to physical injury or excessive fatigue. Workers are often taught principles such as good posture and elimination of excessive wrist movement.

Ergonomics

An approach to designing work tasks that focuses on correct posture and movement.

The basic goal of the biological approach is to eliminate discomfort and injury. Fatigue is reduced by incorporating breaks and opportunities to switch tasks. Short-term gains in efficiency are sometimes sacrificed in order to prevent discomfort or injury. Principles associated with the biological approach can therefore be useful in work that is characterized by sequential processing. Unlike the mechanistic and perceptual approaches, which provide guidance for ways to increase efficiency, the biological approach guides work design specialists in making sure that assembly-line processes do not harm workers. Work design from the biological perspective thus helps organizations with Bargain Laborer or Loyal Soldier HR strategies to balance their quest for efficiency with a focus on the physical needs of workers. A good example is seen in automobile plants, where machines and work surfaces are designed to increase employee comfort and reduce repetitive motions that lead to injuries.

COMBINING WORK DESIGN APPROACHES

A potential problem associated with work design is the sometimes conflicting goals of the various approaches. For instance, the mechanistic approach simplifies processes by assigning workers a few specialized tasks that are rapidly repeated. In contrast, the motivational approach emphasizes whole tasks, high variety, and substantial autonomy. Does increased efficiency come at the expense of worker satisfaction and creativity?

Research has indeed found tradeoffs between the motivational and mechanistic approaches. On the one hand, jobs designed around the motivational approach increase job satisfaction, but the price may be reduced efficiency.61 On the other hand, jobs designed around the mechanistic approach normally improve efficiency, even though job satisfaction may decline.62 Still, studies show that tradeoffs are not always necessary and that in some cases jobs can be designed simultaneously from the mechanistic and motivational approaches.63 In fact, a recently developed Work Design Questionnaire successfully includes measures of work context and task knowledge with social characteristics.64 In this way the combined approach examines tasks in terms of both motivational and mechanistic properties. For instance, someone performing the job of statistical analyst might be given a set of very specialized tasks to improve efficiency but might also have high expertise and autonomy, which would create a sense of responsibility and ownership.65

Combining principles from the mechanistic and motivational approaches can thus lead to jobs that are not only efficient but also satisfying.66 Of course, in many instances the primary consideration will be either efficiency or motivation; the strategic objectives of the organization should be the primary factor that drives work design. The mechanistic approach, incorporating perceptual and biological influences, is most relevant for organizations pursuing cost strategies. The motivational approach provides important guidance when the underlying strategy is differentiation.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4

How Can Work Be Designed to Improve Family Life?

One area of increasing importance for job design is conflict between work and family. Many employees find it difficult to balance their roles as employees with their roles as parents or spouses. This conflict operates in both directions. Stress from problems at home can have a negative influence on work performance, resulting in family-to-work conflict. At the same time, stress encountered at work can have a negative influence on family life, a situation called work-to-family conflict.67 In essence, employees have spillover of work and family stress.68 For example, employees who experience dissatisfaction at work are more likely to be in a bad mood, and to have lower marital satisfaction, when they return home.69 Employees who are more embedded in both their work organizations and surrounding communities seem to experience greater conflict between work and family roles,70 but such conflict is not restricted to workers in the United States. For example, a survey of Australian construction professionals found that strain in the workplace had a negative influence on family relationships.71 Nevertheless, compared to workers in areas such as Asia and South America that value groups over individuals, workers in individualistic societies such as the United States are more likely to be dissatisfied and leave when they feel that their work interferes with family.72

Family-to-work conflict

Problems that occur when meeting family obligations negatively influences work behavior and outcomes.

Work-to-family conflict

Problems that occur when meeting work obligations negatively influences behavior and outcomes at home.

Creating organizational policies that support families can help alleviate work and family conflict. Specific policies include providing flexible spending accounts for dependent care, elder care resources and referral, and child care resources such as on-site daycare.73 Having supervisors specifically support employees by showing empathy and helping balance family and career issues is also critical for reducing work and family conflict.74

One simple reason why work and family roles can conflict is shortage of time. Studies have shown that spending more hours at work creates more stress at home and that spending more hours with family can create stress at work.75 Being able to control work scheduling can, however, buffer some of the stress of not having enough time.76 A second reason for work and family conflict is that the psychological effort required to cope in one area takes away from resources needed to cope in the other.77 A young mother who engages in a difficult confrontation with a coworker is likely to be emotionally exhausted when she returns to her family.

Conflict between work and family roles presents problems for both organizations and employees. From the organizational perspective, increased conflict between work and family roles is a problem because it increases absenteeism and turnover.78 Conflict between roles is a problem for employees because it reduces satisfaction, increases alcohol and drug abuse, and results in poor physical health.79 These problems tend to be particularly difficult for women.80 Constraints from family duties that inhibit them from accepting international assignments is one particular example of negative family–work conflict for women.81

Some organizations are, however, effective in structuring work in ways that help decrease conflict between work and family roles. IBM, which is profiled in the next “Building Strength Through HR” feature, is a good example. One key for IBM and other organizations that minimize work and family conflict is to be seen as fair by employees.82 People working in these organizations report going beyond minimum expectations by helping coworkers and suggesting ways to improve work processes.83 This extra effort appears to translate into higher organizational performance. Organizations perform better when they incorporate family-friendly policies and procedures, such as daycare and elder-care assistance, paid parental leave, and flexible scheduling.84 Some of these policies concern benefits and services, which we discuss in later chapters. But other family-friendly practices, such as flexible scheduling and alternative work locations, relate to job design.

FLEXIBLE WORK SCHEDULING

Dual-career households are common in the United States. Parents in these households can often benefit from flexible work scheduling that allows them to coordinate the many demands on their time. Flexible scheduling practices allow people to coordinate their schedules with a partner and thereby reduce the conflict associated with being both a parent and an employee. The potential benefits are so high that most large organizations provide some form of flexible scheduling.85 Two of the most common forms of flexible scheduling are flextime and the compressed workweek.

Flextime

Flextime provides employees with the freedom to decide when they will arrive at and leave work. The organization creates a core time period when all employees must be present. For example, a bank may require all tellers to be at work between the busy hours of 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. Outside of this core band, employees can work when they wish. Some may choose to arrive at 7 a.m. so they can go home early. Others may choose to arrive at 11 a.m. and leave at 8 p.m. This flexibility allows employees to better balance work with family and other demands.

Flextime

A scheduling policy that allows employees to determine the exact hours they will work around a specific band of time.

As you can probably imagine, some work design problems can arise with flextime. Employees who must work with others on projects might find it difficult to coordinate their efforts with coworkers who work on different schedules. Supervision can also be a problem if employees are working when no supervisor is present. These work design issues tend to limit flextime to nonmanufacturing positions that do not require close supervision or ongoing sequential processing.86 Flextime is thus most useful for organizations pursuing differentiation strategies.

Even with potential difficulties, many organizations that allow flextime appear to reap substantial benefits. Flextime is associated to some extent with higher productivity, but the primary benefit is increased satisfaction among workers. In turn, workers are absent less frequently and are more likely to remain with the organization.87 Flextime is thus most consistent with the motivational approach to job design.

Compressed Workweek

A compressed workweek enables employees to have full-time positions but work fewer than five days a week. Typically, employees with compressed schedules work four 10-hour days. Allowing employees to have three-day weekends can provide them with additional time for family activities. A compressed workweek may make it easier to schedule events such as doctor and dentist appointments, for example. Commuting on four rather than five days can also reduce time and expenses spent traveling.

Compressed workweek

Working more than eight hours in a shift so that 40 hours of work are completed in fewer than five days.

As with flextime, employees who work a compressed workweek report higher levels of job satisfaction; they also have slightly higher performance. Unlike flextime, the compressed workweek does not appear to decrease absenteeism.88 It thus appears that providing flexibility each day may be more beneficial for reducing absenteeism than providing a designated day off each week. However, compressed workweeks may be more feasible than flextime in organizations that use assembly lines. Employees can be scheduled to work at the same time each day, and setup costs can be minimized by longer shifts. Using compressed workweeks does not seem to compromise principles associated with the mechanistic approach to job design, but the longer hours may create fatigue, which is at odds with the biological perspective. Because of its compatibility with assembly-line processes, the compressed workweek seems to be best suited for organizations with Loyal Soldier HR strategies.

ALTERNATIVE WORK LOCATIONS

Many organizations allow employees to work at locations other than company facilities. The most common arrangement is for employees to work at home. This practice is often called telework, since employees stay connected with the office through voice and data services provided over telephone lines. Over 80 percent of companies report at least some employees doing telework, and 45 million people in the United States spend at least some of their time teleworking.89 As described in the “Technology in HR” feature, telework is fundamental for many organizations.

Telework

Completion of work through voice and data lines such as telephone and high-speed Internet connections.

Researchers evaluating telework have created a list of suggestions to improve its effectiveness. One critical suggestion is to use care in choosing the employees who are allowed to do telework. Most likely to succeed are employees who are independent and conscientious, and employees should embark on telework only after they have physically worked in the office for some time so that they can develop relationships and prove themselves worthy of the opportunity to work at home. A second critical suggestion is that telework should be limited to jobs where it is most appropriate; these jobs often involve word processing, Web design, sales, and consulting. A common characteristic of these jobs is the existence of clear performance objectives and methods for measuring outputs.90

In the end, telework offers substantial autonomy and usually requires employees to work independently to complete meaningful tasks. Telework is thus consistent with the motivational approach to job design. Given the need for workers in most jobs to process substantial amounts of information, principles from the perceptual approach can also be important for properly designing telework. In particular, companies need to focus less on work processes and more on establishing clear goals and performance measures. This means that telework is most likely to occur in organizations that are pursuing differentiation strategies.

Work design practices should align with overall HR strategy. Organizations that pursue either Loyal Soldier or Bargain Laborer HR strategies benefit from efficiency. Efficiency comes from designing work so that employees have relatively little autonomy, meaning that they have little freedom to alter the way tasks are carried out. Efficiency is also increased with sequential processing, which occurs when people use assembly lines to complete work tasks. Competitive strategy that focuses on cost reduction thus aligns with work design practices that limit autonomy and create sequential processing.

Organizations that pursue either Committed Expert or Free Agent HR strategies benefit from innovation and creativity. Innovation comes from designing work so that employees have substantial autonomy, meaning that they have freedom to make decisions and ongoing adjustments to the work process. Reciprocal processing, which occurs when employees work closely together and share tasks, also leads to higher creativity. Competitive strategy that focuses on differentiation thus aligns with work design practices that provide high autonomy and create reciprocal processing.

There are seven steps in the job analysis process. (1) Get organized by determining who will do the analysis and by gaining the support of top management. (2) Choose jobs that are critical for success and have a sufficient number of employees. (3) Review what has already been written about the job. (4) Select job agents, such as incumbents, supervisors, or experts. (5) Collect job information through interviews, questionnaires, and observations. (6) Create a job description that specifies the actions that workers do when performing the job. (7) Create job specifications that list the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics that workers need in order to successfully perform the job.

In order to guide other human resource practices, job analysis information needs to be translated into a “shopping list” of the characteristics needed by people who perform the job. Some worker-oriented job analysis procedures, such as the Position Analysis Questionnaire, provide a list of characteristics that employees need to succeed at the job. In most cases, the information in a job description needs to be translated into a list of desired worker characteristics. Job agents can do this by examining lists of duties in the job description and determining the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics that workers need to perform the required tasks. Competency modeling, an alternative to traditional job analysis, seeks to determine a list of desirable worker characteristics linked to the strategic objectives of the organization.

In the mechanistic approach to job design, principles of scientific management are used to determine the most efficient methods for completing work tasks. Each employee is expected to learn and follow procedures that result in producing goods and services as quickly as possible. The motivational approach is concerned with designing jobs to increase workers' intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation arises when employees feel that their work provides meaningfulness, responsibility, and knowledge of results. When the perceptual approach is used, jobs are designed so that workers can easily process important information. Equipment is developed to simplify work, and accident prevention is a focus. The biological approach involves designing jobs to prevent physical injury. Equipment is used to reduce fatigue and need for excessive movement. Workers are also taught principles such as maintaining good physical posture.

There are some inherent tradeoffs associated with the various approaches to work design. In many cases, striving for efficiency by adopting the mechanistic approach comes at the expense of the principles of the motivational approach. The job design approach should thus be aligned with the overall HR strategy. The mechanistic approach is most appropriate for cost strategies, whereas the motivational approach is most appropriate for differentiation strategies. Yet, benefits can be obtained from simultaneously incorporating principles from all approaches.

Workers experience work-to-family conflict when the stress they feel at work is carried into their family environment. They experience family-to-work conflict when the stress they encounter at home affects their work. One way to reduce conflict between work and family roles is through flexible scheduling, including flextime and compressed workweeks. Another way to reduce work and family conflict is to allow workers to perform their tasks in alternative locations, such as at home or on the premises of clients. This practice is often referred to as telework because employees communicate with others via telephone lines. Employees who can take advantage of flexible work scheduling and working at alternative locations are more satisfied with their jobs, more productive, and less likely to leave the company.

Autonomy 124

Competencies 138

Competency modeling 138

Compressed workweek 148

Critical-incidents technique 134

Differentiation 122

Ergonomics 144

Family-to-work conflict 146

Flextime 147

Integration 122

Interdependence 126

Job 128

Job analysis 128

Job analysis interview 131

Job analysis observation 132

Job analysis questionnaire 131

Job characteristics model 142

Job description 132

Job design 140

Job redesign 140

Job specifications 132

Occupational Information Network 131

Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ) 134

Reciprocal processing 126

Scientific management 141

Sequential processing 126

Task analysis inventory 133

Telework 148

Work design 122

Work-to-family conflict 146

- Why is high autonomy beneficial for organizations pursuing differentiation strategies?

- What are the key differences between sequential and reciprocal processes of interdependence?

- Why would government officials expend significant resources creating O*Net? What are the benefits of O*Net?

- Have you ever seen a job description for a work position you have held? If so, do you think the job description was accurate?

- Are job descriptions more beneficial for some types of organizations than others? Could having specific job descriptions harm an organization?

- Would you rather work in an organization using mechanistic job design principles or an organization using motivational principles?

- Do you think any of the four job design approaches (mechanistic, motivational, perceptual, biological) will become more important in the future? Why? Do you think any of the approaches will become less important as organizations change?

- Would you like to work a compressed workweek? Why or why not?

- Do you think you would be successful in a job that allowed you to do telework? What challenges do you think you would face?

- Identify some specific ways strategic work design can guide other human resource practices, such as selecting employees, determining training needs, and making pay decisions.

Often, the success of hospital-based nursing depends on its adaptability. Nurses can ensure that success when they think outside of traditional nursing roles and focus on effective ways to deliver care. You'll most likely find our assignment familiar: reduce costs, improve quality and access to care, and improve satisfaction for patients and caregivers. This is no small feat, and it requires caregivers to innovate new ways to care for patients.

To start the work redesign, they created a steering committee to collect and analyze data and create the new design. The committee included nurses from administration, education, middle management, and direct care providers, as well as nurses with differing credentials (RN and LPN) who work all shifts.

The committee agreed that staff satisfaction, leading to increased autonomy and control, would be one of its priorities while developing the new model. The committee had a threefold objective:

- Develop a nursing model that will more efficiently utilize RNs, LPNs, and unlicensed assistive personnel within quality standards.

- Give staff attractive and satisfying roles.

- Stay within the current budget.

The committee collected data through surveys, interviews, onsite observations, and work sampling. Topics for data collection included:

- The efficiency of nursing care delivery (focusing on nursing and nonnursing tasks)

- The impact of managed care on the nurse's role

- Issues that occupy the nurse's time, affect staffing, and create chaos Patient management throughout the hospital stay, including ways to decrease length of stay

- Nurse–physician communication

- Working relationships across departments

Each committee member took part in gathering the data and presenting it to the committee. Members defined and redefined roles based on the actual and described job performances of RNs, LPNs, and unlicensed assistive personnel. They also identified problem areas in the delivery system.

Next, they needed to write a work redesign proposal. The committee members wrote wish lists for the nursing model redesign with input from their peers and presented them to the committee.

With the newly designed jobs, certain registered nurses (admission nurses) would work to help transition patients to the units, maintaining the continuum of care. The nurse's primary responsibility would be to minimize admission delay at the point of entry and to make this experience less distressing to patients. Today, the admission RN interviews the patient, develops a care plan, explains procedures, and tries to alleviate the patient's anxiety.

Nurses work at the other end of the continuum as well. Discharge RNs work with other disciplines to plan expedient discharge. Their primary objectives are to ensure that the patient leaves the hospital without any delays in the discharge process and that he or she experiences favorable outcomes.

Discharge RNs also emphasize patient education and follow-up appointments. They call the patient the day after discharge to ensure that he or she

- Understood instructions

- Could obtain medications and is taking them properly

- Gets an earlier follow-up appointment if necessary

- Was satisfied with hospitalization

Positive results of this new process include the following: