How Can a Strategic Compensation Package Make an Organization Effective?

Chapter 11 discussed principles of motivation and described the concepts of pay level and pay structure. In this chapter, we extend these ideas by examining specific components of compensation packages. A compensation package represents the mix of rewards employees receive from the organization. Money paid as wages or salary is the largest component of most compensation packages. Some workers are paid a fixed amount for each time period, but for others the amount varies with performance. In these situations, determining the percentage of pay that will depend on performance is an important compensation decision. When pay is linked to performance, another important decision concerns whether the amount paid will depend on individual performance, the performance of a work group, or the performance of the organization as a whole. Still another part of the compensation package is made up of employee benefits such as health insurance and retirement savings, and organizations must decide what proportion of employees' compensation will take this form. In making all these important compensation decisions, as in making decisions about other human resource practices, a key to success is to ensure that the decisions align with organizational strategy.

Compensation package

The mix of salary, benefits, and other incentives that employees receive from the organization.

An example of an organization that aligns compensation practices with competitive business strategy is IKEA, which manufactures and sells Scandinavian furniture at low prices. The company's first showroom opened in Sweden in 1953. Today, IKEA has grown into a global retailer operating in 38 countries. Total sales exceed $35 billion per year.1

IKEA's competitive strategy is cost reduction. Ingvar Kamprad, the company founder, was born in a relatively poor province in Sweden. He grew up in a frugal community with limited resources. This upbringing helped shape his entrepreneurial goal to offer functional furniture at very low prices.2 In fact, the vision for IKEA today is to create a better everyday lifestyle for many by offering a wide range of well-designed, functional products at prices that as many people as possible can afford.3 The cost-cutting strategy is carried out so effectively that prices on the same products often fall from one year to the next.4

IKEA reduces costs by building showrooms where customers serve themselves. Each store is staffed by a limited number of salespeople, who are different from typical furniture salespeople. Instead of using high-pressure sales techniques, associates at IKEA generally stand in the background and seek to be helpful when customers ask them for assistance or when they observe customers needing help. Once they make a purchase, customers are expected to help lift and load furniture, as well as assemble it.5 These staff reduction practices allow IKEA to hire fewer employees, which reduces payroll costs.

Consistent with the low-cost strategy, most employees at IKEA are paid a relatively low hourly wage. Efforts are made to treat everyone the same. A good example occurred a few years ago when the total dollar value of sales for the entire company on a particular day was split evenly among all employees. All managers and staff members received the same amount.6 Since employees tend to be treated similarly regardless of performance, few workers make much more than minimum wage. IKEA also minimizes long-term compensation such as stock options. Yet a substantial number of potential workers apply for each open position, and employee turnover is quite low for the industry.7 So why do employees choose to work at IKEA?

The key to effective compensation at IKEA is benefits. Employees don't generally choose to work at IKEA because they receive high wages. They choose IKEA because they feel that IKEA provides them with an opportunity to balance work with other aspects of life. Employees don't expect to receive cash bonuses. Rather, IKEA retains employees with incentives such as flexible scheduling and generous healthcare plans. Almost the entire expense for health and dental insurance is paid by IKEA. Full medical and dental benefits are offered to part-time employees who work at least 20 hours per week. Once workers have been employed for a year, they become eligible to participate in a retirement savings program where IKEA pays up to 3 percent of salary into a retirement fund.8 Perhaps most important, employees are allowed to use flextime and job sharing to help them meet family demands.9 IKEA also tries to provide employees with the opportunity to improve themselves through benefits such as tuition assistance and discounts for weight loss and smoking cessation programs.

IKEA thus uses compensation to help attract and retain a specific type of worker. The best employees are not superstar individual performers but rather solid team players. They value frugality and life balance more than high monetary rewards. Interestingly, almost half of IKEA's top earners are women.10 As a whole, employees appreciate the opportunities offered by IKEA enough that the company is ranked as one of Fortune's “100 Best Companies to Work For.” The end result is a workforce of highly committed employees who feel they are valued and treated fairly even though they do not receive extraordinarily high wages. Motivating with benefits rather than high wages is thus a critical aspect of IKEA's strategic effort to reduce cost. The cost reduction strategy has been effective during the recent recession, as IKEA focused on expanding and taking market share from other companies that sell furniture at higher prices.11

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

How Do Compensation Packages Align with Strategy?

Much of IKEA's success can be traced to alignment between competitive strategy and compensation. Compensation practices help reduce labor costs, which in turn helps IKEA meet its strategy of producing and selling goods at the lowest possible price. However, the practices that best support this low-cost strategy may be very different from the practices that are best for a company pursuing another strategy. A company must carefully consider its strategic objectives when designing a package of wages and benefits. In this section, we discuss elements of strategic design for compensation packages.

AT-RISK COMPENSATION

One element of strategic design is the amount of pay to place at risk. At-risk pay is compensation that can vary from pay period to pay period. The money is at risk because the employee will not earn it unless performance objectives are met. You can understand the issues associated with at-risk compensation by thinking about two different grading options that a professor might offer students. One option is for students to receive a B grade if they attend all classes and complete all assignments. There is relatively little risk with this option. Simply being in class and doing the work is enough to receive the B grade. The second option is riskier. Students choosing the second option will have all their assignments scored and receive a grade based on performance. Students who perform well will receive a grade higher than B, but those who perform poorly will receive a grade lower than B. Which of the options would you prefer? Would your actions and study habits be the same with both options?

At-risk pay

Compensation where the amount varies across pay periods depending on performance.

The notion of at-risk pay relates to the motivational theories discussed in Chapter 11. Reinforcement theory and expectancy theory suggest that motivation is higher when at least some pay is at risk. Thus, most students work harder when their assignments are scored and reflected in an overall grade. Agency theory also suggests that when people bear the risk for outcomes, they want the opportunity to earn higher rewards. In the grading example, students will choose the second option only if there is a chance that they can earn a grade higher than the B that is guaranteed in the first option.

In practice, most compensation packages include some at-risk pay and some guaranteed rewards. The key to aligning compensation and strategy is to determine how much of the compensation to place at risk. On the one hand, organizations pursuing a differentiation strategy generally seek to hire and retain individual high performers. These organizations succeed by encouraging employees to exceed minimum expectations. Organizations can do this, in part, by offering employees strong incentives that place a substantial amount of compensation at risk.12 Placing a high proportion of pay at risk is thus common for organizations pursuing differentiation strategies. In contrast, organizations with cost leadership strategies, such as IKEA, prefer that employees make consistent contributions. Consistency is encouraged by rewarding employees who loyally complete basic tasks. A relatively low percentage of at-risk pay is thus common for organizations pursuing cost reduction strategies.

LINE OF SIGHT

Another element of strategic compensation packages concerns employees' perceptions of their ability to influence important outcomes. It is important for employees to perceive that their actions truly influence the outcomes used for determining whether they receive a particular reward. In other words, employees' motivation increases when they are rewarded for outcomes that are within their line of sight.

Line of sight

The extent to which employees can see that their actions influence the outcomes used to determine whether they receive a particular reward.

Students who have worked on both group and individual assignments have experience with the line of sight concept. Line of sight is clear for individual assignments. Students can see how personal effort on an individual assignment is an important determinant of the grade they receive. The value of working hard is less clear for many group assignments, since the grade is determined by the inputs of many individuals. Students may not be motivated to work hard on group projects unless they feel their inputs will truly influence the overall grade. For any one person, the line of sight is more distant, and therefore less motivating, for group projects.

Like at-risk pay, line of sight has important connections with the motivational theories presented in Chapter 11. Expectancy theory suggests that people are motivated only when they believe their efforts will result in higher performance. Justice theory points out that motivation is higher when people believe that individuals with greater inputs receive better rewards. In the group grade example, these principles suggest that students will not work hard in groups unless they believe that their efforts will influence the final grade and unless they believe that members of the group who contribute more will be recognized with higher individual rewards. Effective compensation packages incorporate the line of sight principle. For example, a consulting firm might offer an accountant a bonus for receiving high ratings from a client where the accountant has been assigned to work. This action makes more sense than offering a bonus for overall corporate sales, as the accountant may be able to do little to influence sales to other clients. We will use the line of sight concept as we discuss various elements of compensation packages, and particularly as we discuss the relative value of rewarding employees either for individual contributions or for group contributions.

COMMON ELEMENTS OF COMPENSATION PACKAGES

Compensation packages are best when adapted to fit the unique needs of a specific organization. The “Building Strength Through HR” feature illustrates how three companies altered their pay practices in order to face the challenge of a recession. Each of these approaches was very different depending on the organization's circumstances. Basic elements of compensation, however, are common across organizations. One element is base pay. Base pay is a form of compensation that is not at risk and may consist of an hourly wage or an annual salary. As explained in Chapter 11, a certain level of base pay is often required by minimum wage laws. Base pay gives employees a sense of security and provides them with a minimum guaranteed reward for joining an organization. Base pay is not contingent on performance, which makes it relatively ineffective for motivating performance.

Base pay

Compensation that is consistent across time periods and not directly dependent on performance level.

Another element of compensation packages that is usually not at risk is the employee benefit package. Employee benefits, as we've already seen, are rewards other than salary and wages. Organizations are required by laws and tax regulations to provide similar benefits to all employees. Benefits thus represent an element of compensation that is not at risk. Benefits also represent a form of long-term compensation that builds loyalty and binds employees to an organization. This makes benefits a valuable component of compensation plans for organizations with an internal labor orientation.

Employee benefits

Rewards other than salary and wages; typically include things such as retirement savings and insurance.

One common form of at-risk reward is the individual incentive. An individual incentive is a reward that is based on the personal performance of the employee. Individual incentives can easily be linked to performance behaviors and outcomes. These incentives thus have a clear line of sight, which makes them powerful motivators. Yet, individual incentives also have the potential to destroy cooperation among employees. Workers who focus too much on achieving high individual performance often harm the overall performance of the group.13 Individual incentives must therefore be carefully structured to encourage personal effort without destroying group cooperation. At the individual level, paying people by the hour rather than a salary has also been found to make employees much more conscious of the value of time,14 which can increase their motivation. Focusing on time can, however, have negative effects such as employees being less willing to volunteer to do tasks for which they are not paid.15

Individual incentive

A reward that depends on the performance of the individual employee.

Another form of at-risk reward that is common in compensation packages is the group incentive. A group incentive is a reward based on the collective performance of a team or organization. Because individual incentives can harm cooperative effort, many organizations use group incentives to focus workers' attention on contributing to the shared goals of the broader group.16 However, group incentives present their own problems. The main problem occurs when line of sight is so distant that individual workers fail to provide maximum personal effort.17 Effective group incentives must therefore encourage individuals to contribute maximum personal effort in order to assure the success of the team or organization.

Group incentive

A reward that depends on the collective performance of a group of employees.

One important decision in constructing the package is how much of overall compensation will be guaranteed and how much will be at risk. Compensation packages with comprehensive benefits and high percentages of base pay place very little of the reward at risk. If a package includes at least some at-risk compensation, then the next critical decision concerns the mix of individual and group incentives. Both types of incentive have strengths and weaknesses, and differences in the line of sight must be taken into account to encourage cooperation without diminishing individual motivation. Figure 12.1 captures critical decisions by illustrating how base pay, benefits, individual incentives, and group incentives combine to create an overall compensation package. The following sections describe the four elements of compensation shown in the figure, along with the strengths and weaknesses associated with choices related to each element. Once we have discussed the basic issues associated with each of the four compensation package elements, we will further explore how the elements can be combined to support an overall HR strategy.

Figure 12.1 Combining Compensation Package Elements.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

What Are Common Approaches to Base Pay?

As noted earlier, base pay is compensation that is provided for time worked; it is not contingent on performance. Base pay provides employees with stability, because it enables them to plan and budget their personal finances. Some people prefer not to take risks and are therefore attracted to organizations that guarantee them a specific income. From the organization's standpoint, base pay is simple to calculate. In practice, most organizations combine base pay with other incentives. Base pay provides a security net for employees, whereas individual and group incentives provide rewards for high performance.

As explained in our discussion about pay structure in Chapter 11, there are two basic methods for allocating base pay. The first uses job-based analysis. Each job is evaluated with a point system, and base pay is set at a higher level in jobs worth more points. The second method for allocating base pay uses skill-based analysis. Skill sets are defined in terms of the number of tasks that an employee is capable of performing. Employees who are able to perform more tasks are paid a higher base wage. As explained in Chapter 11, job-based and skill-based methods have different strengths. Job-based methods appear to be less biased and provide employees with higher compensation when the tasks they do require more knowledge and skill. Skill-based methods provide employees incentives to learn new skills.

Regardless which method is chosen, organizations must establish a base pay rate that determines compensation for individual workers. The rate is partially a function of the pay level decision that was discussed in Chapter 11. Organizations with lead-the-market strategies will need to establish a higher compensation level than organizations with lag-the-market strategies. Yet simply establishing a pay level is not the only step in establishing base pay. The overall pay level includes both base pay and incentives. The main question is therefore what percentage of overall pay will be provided as base pay and what percentage as incentive pay. In general, organizations that seek innovation and higher individual performance place a larger percentage of total compensation at risk. Although some companies such as Netflix, which is described in the Building Strength Through HR feature go against the grain to use high base pay as part of other strategies, base pay is usually a higher percentage of overall compensation in organizations that pursue Bargain Laborer and Loyal Soldier HR strategies.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

What Are Common Employee Benefit Plans?

Common employee benefits include health insurance, retirement savings, and pay without work. Before the 1930s, employee benefits were rare. However, President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal legislation altered tax incentives in ways that encouraged organizations to provide employees with benefits. The overall objective was to increase the likelihood that individuals would receive basic services, such as healthcare. The percentage of total compensation provided through benefits grew steadily until the 1970s, when it reached approximately 25 percent. Over the past 30 years, the growth in benefits has leveled off, and benefits now represent approximately 30 percent of an organization's labor costs.18

Favorable tax rules explain most of the trend toward increased employee benefits. Employees must pay taxes on the money they receive as wages and salary, but they are generally not required to pay taxes on the benefits they receive. This means that organizations can use benefits to provide more value to employees. For instance, assume an organization pays an employee a salary of $10,000 per month. If the employee pays a total of 25 percent of this amount in taxes, then the take-home value of the compensation is $7,500. However, suppose the compensation is provided as $3,000 worth of benefits and $7,000 worth of salary. Because benefits are not taxable, the total value of the compensation to the employee increases. With an average tax rate of 25 percent, the additional value for the employee is $750 ($3,000 × 0.25). In addition, the cost of purchasing things like healthcare insurance is usually higher for individuals than for large organizations. Using benefits is thus a way for organizations to provide greater rewards to employees without increasing overall labor costs.

Providing good benefits is an important tool that helps an organization attract and retain high-quality employees.19 Unfortunately, many organizations fail to obtain the maximum value from employee benefits. Most employees significantly underestimate the amount of money that organizations spend on benefits.20 Clearly communicating the monetary value of employee benefits is thus an important step toward maximizing the contribution of the benefits package to the overall compensation strategy.

Employee benefits can be placed into two broad categories. One category includes benefits that are required by law. The other category consists of benefits that organizations voluntarily provide to employees.

LEGALLY REQUIRED BENEFITS

Legally required benefits are mandated by government regulations. The regulations are designed to protect people from hardship associated with not being able to work and earn a living. Protection is given to workers who are injured, laid off, or past the age when they might be expected to work. Recent legislation in the form of the Affordable Care Act—often referred to as Obamacare—also requires large organizations to provide healthcare benefits to full-time employees. Because legally required benefits must be given to all workers in specified amounts, it is difficult for an organization to use them to create a workplace that is more attractive than competitors. However, there are ways organizations can use some of these benefits strategically. We explain some of these strategic choices In the following sections as we discuss specific types of benefits.

Social Security

In the early days of the United States, most people lived together in extended families engaged in farming. Families worked together and helped individuals whose age or health prevented them from working. As more people moved into cities, this reliance on families became less common, creating a need for other sources of support for elderly and disabled people. The Great Depression that began in the late 1920s also created severe economic hardship for many people. These needs resulted in the Social Security Act of 1935, which began the establishment of government programs aimed at providing financial security for retired and disabled workers. The Social Security Act created a social security system in which workers pay into a fund and then draw from the fund when they retire. With few exceptions, all U.S. workers are required to participate in social security. Approximately 98 percent of U.S. workers are now covered by social security.

Social security system

A federal program that requires workers to pay into a retirement fund, from which they will draw when they have reached a certain age.

Current regulations require both the employee and the organization to contribute 7.65 percent (15.3 percent total) of wages and salary up to a certain amount to the social security fund. Upon retirement, participants in social security receive a monthly payment. The original age of eligibility for receiving social security was 65. A subsequent amendment made people eligible for partial benefits at age 62. Recent changes gradually increased the age of eligibility for full retirement benefits, ending with a full retirement age of 67 for people born in 1960 or later.21

Since its creation, social security has been altered so that spouses and dependent children receive benefits if a worker dies before the age of retirement. Spouses and dependent children also continue to receive benefits if the worker dies after beginning to receive social security. A change in 1954 extended benefits to include disability insurance. Individuals who are disabled receive monthly payments similar to those received by retired workers. Other changes during the 1960s created Medicare, which provides health insurance to social security beneficiaries. Social security is thus a mandatory benefit provided to almost all retired and disabled individuals, as well as to surviving spouses and dependent children. Although the amount of benefit is not adequate to fully support many lifestyles, social security provides many retired workers with at least a minimum level of financial security.

Unemployment Insurance

The Social Security Act of 1935 also created incentives for states to provide workers with unemployment insurance. The act created a 3 percent tax on the payroll of organizations with eight or more employees. However, the act allowed the tax to be offset by contributions to state unemployment funds. This resulted in a system wherein each state has an unemployment insurance program that provides protection for workers who lose their jobs through no fault of their own.22

Unemployment insurance

A network of state-mandated insurance plans that provide monetary assistance to workers who lose their jobs through no fault of their own.

Although unemployment insurance differs somewhat from state to state, the presence of federal guidelines means that the state programs are highly similar. In general, to qualify for unemployment insurance, an individual must have been employed for a minimum amount of time (usually a year). In addition, the individual must have been discharged from the job for a reason that was outside his or her control. Unemployment insurance is not available to people who quit voluntarily or to people who are fired because of things such as theft or failure to follow organizational rules. In order to continue receiving benefits, individuals must demonstrate that they are actively seeking employment.

People receiving unemployment insurance normally receive a weekly sum equal to half the amount they were paid each week when they were employed. Recipients must file frequent claims that document any earnings or job offers. Unemployment benefits normally last 26 weeks but can be extended when the overall rate of unemployment is high enough to suggest that it is particularly difficult to find a job.23

With a few exceptions in states where employees pay a small portion, unemployment insurance is funded entirely by contributions from employers. However, not every employer pays the same percentage. Organizations that have frequent layoffs are assessed a higher rate than organizations that provide stable employment. This provides an incentive that discourages employers from frequently laying off workers. Minimizing employee layoffs is thus one way that an organization can take a strategic approach to legally required benefits.

Workers' Compensation

Chapter 3 discussed health and safety issues for workers. As explained in that chapter, all states have workers' compensation programs, which provide workers with compensation when they suffer work-related injuries. Because workers' compensation is no-fault insurance, individuals receive benefits even if their own carelessness caused the accident. Workers' compensation provides several specific benefits:

Workers' compensation

State programs that provide workers and families with compensation for work-related accidents and injuries.

- A percentage of weekly wages is paid to employees during the time when they are unable to work because of the accident.

- Medical expenses and rehabilitation costs are paid to injured workers.

- Money is paid to workers who are permanently disabled, or to families of workers who die because of a work-related accident.

The amount that organizations pay to obtain workers' compensation insurance depends on both the nature of the industry and the accident history of the employer. Organizations engaged in dangerous work, and those that have high accident rates, pay more than those that provide a work environment with little risk of accident or injury. This provides an incentive for organizations to take precautions to protect the safety of workers, which is once again a way for organizations to strategically benefit from legally required benefits.

Healthcare Plans

Until recently healthcare benefits were classified as discretionary. However, in March 2010 the Affordable Care Act was passed to significantly alter healthcare. The overall objective of the legislation was to provide greater access to healthcare. For many employers the effect was to make the provision of a healthcare plan legally required. Although healthcare is still not a mandatory benefit for all employees, we will discuss healthcare plans in this section.

Healthcare plan

An insurance plan that provides workers with medical services.

The Affordable Care Act is complex and takes over 2,000 pages to present. There are, nevertheless, a few key issues that affect organizations and employees. For example, beginning in 2010 a benefit that many university students realized is their being able to remain on their parents' health insurance policy until the age of 26. Most of the other provisions phase in over time, with the following benefits being implemented in 2014:

- All individuals, except those with very low incomes, are required to have health insurance or pay a fine.

- Companies with more than 50 employees must pay a fine unless they provide health insurance coverage to all full-time employees (implementation of this benefit has been delayed an additional year).

- Small businesses with fewer than 50 employees receive tax credits when they provide health insurance coverage to their employees.

- A Health Insurance Marketplace allows individuals and small businesses to purchase health plans through healthcare exchanges.

- People who are less affluent receive tax credits to help them purchase health insurance, or they receive care through Medicaid.

- Insurance companies cannot cancel or deny coverage to someone who is ill.

In 2012, approximately 73 percent of workers had access to healthcare benefits through their employer, and over 59 percent were actually enrolled in a health plan. As part of the average benefit plan, the typical organization paid about 80 percent of the cost of healthcare insurance, with the average employee paying about $90 per month for individual coverage and over $350 for family coverage.24

Healthcare plans have now become a required benefit, which has benefits in line with those advocated by many companies, given that a majority of company executives believe a good healthcare plan can improve employee health and in turn increases worker productivity.25 It is instructive, nevertheless, to briefly review the history of health insurance, as well as typical plans that are currently provided.

Many years ago, healthcare plans provided only basic insurance that covered expenses for major medical conditions. For example, healthcare costs might have been paid for an employee with cancer. The purpose of these plans was to protect employees from unexpected costs associated with major medical problems. Over time, these plans evolved to provide coverage not only for major medical conditions but also for routine healthcare. Evolving plans appear to have resulted in increasing healthcare costs. Employees who only pay a portion of the cost often purchase more services than they would if they were required to pay the full cost. Furthermore, patients and doctors have little incentive to control the cost of healthcare, as most of the expense is paid by the insurance company.

Escalating medical costs are a crucial concern of most modern organizations, as healthcare represents the largest benefit cost for most organizations, and recent estimates indicate that the cost of health insurance is growing twice as fast as inflation.26 Substantial effort has thus gone into finding ways to decrease healthcare costs. One trend to reduce health costs has been the move to health maintenance organizations (HMOs). An HMO is a prepaid health plan with a specific healthcare provider that supplies health services to clients for a fixed rate. Approximately 30 percent of the U.S. population is enrolled in some type of HMO.27 In most cases, the employer contracts with the HMO to pay a fixed amount per person covered by the plan. Employees who are enrolled in the HMO plan then pay a small fee each time they receive health services. Covered employees must receive their healthcare from providers within the HMO. Because the HMO receives a fixed amount from the organization, it will not benefit from providing extra services. The HMOs thus have an incentive not to recommend or deliver unnecessary care. The downside to such a plan is that employees enrolled in HMOs are required to receive care only from approved providers, resulting in a perception that HMO plans are inflexible. HMOs are also sometimes accused of rationing services so that people do not receive the treatments they need. Many medical providers also refuse to participate in HMOs because they receive a lower rate of reimbursement for services.

Health maintenance organization (HMO)

A healthcare plan under which the provider receives a fixed amount for providing necessary services to individuals who are enrolled in the plan.

A more recent trend in healthcare is to provide employees with health savings accounts (HSAs), which are personal accounts that people use to pay for health services. HSAs represent a new option for funding healthcare that began as part of the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Even though the employer may pay into the HSA, it is the employee who establishes and owns the account. An HSA can be set up with a bank, credit union, or insurance company. Money placed into the HSA is not subject to taxes and can be used only to pay for approved medical services. In many ways, HSAs are similar to flexible spending accounts—accounts into which an employer places tax-free money that an employee can use to pay for medical services received. The major difference is that money placed in an employer-sponsored flexible spending account must be spent during the year in which it is saved. With an HSA, the money can be carried over and used in subsequent years.28

Health savings account (HSA)

A personal savings account that an employee can use to pay healthcare costs.

HSAs are usually combined with high-deductible health insurance plans. A high-deductible insurance plan requires the employee to pay a relatively large sum before the insurance plan pays anything. This helps reduce overspending by providing an incentive to consumers to minimize costs. Government rules allow HSAs to be used when the insurance deductible is between $1,050 and $5,250 for individuals and between $2,100 and $10,500 for families. For example, an organization may provide an individual employee with healthcare insurance that has a deductible of $3,000. Here, the employee must pay the first $3,000 of healthcare expense during a year. The money to pay for these expenses can come from an eligible HSA.29

Some argue that the combination of high-deductible insurance and HSAs could change the way people approach healthcare spending. Employees have an incentive to reduce the amount they spend on healthcare. In a given year, they need not make contributions to their HSAs if the accounts still contain money from the previous year. This means that employees who don't spend their HSA money one year can increase their take-home pay in subsequent years by not having to pay money into the HSA. This helps alleviate the problem of employees paying little attention to the cost of health services. In the end, such plans become more like traditional insurance plans that provide coverage for major medical conditions while individuals pay for routine items such as visits to physicians. Although they are still new, HSA plans are increasing in popularity. Companies such as Walmart and Target are adopting health plans with high-deductible insurance and HSAs.30 Indeed, recent estimates suggest that over 60 percent of employers are using or planning to use HSAs.31

One concern associated with this new trend toward high-deductible insurance plans and HSAs is that people who are generally healthy will move to these plans, leaving only those with severe medical problems in traditional insurance programs. If people who are relatively healthy do not enroll in traditional plans, then the cost per person enrolled in the traditional plan will increase, which in turn is likely to raise the cost of healthcare for people who have severe health problems. In the end, this could make it difficult for people with severe health problems to obtain healthcare.32

DISCRETIONARY BENEFITS

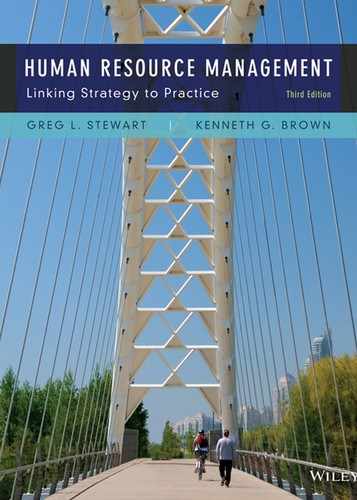

Most organizations offer employees a benefit package that extends beyond what is legally required. Offering more than what is legally required provides an opportunity for organizations to use benefits as a tool for attracting and retaining employees. Common discretionary benefits include supplemental insurance, retirement savings, pay without work, and until recently healthcare plans. Figure 12.2 shows the percentage of employees who receive various types of discretionary benefits.

Before discussing the various types of benefits, we should point out that even though they are discretionary, these benefits are subject to government regulations. Organizations are not legally required to offer these benefits. However, if they do, they must follow certain guidelines to ensure that good benefits are not being provided only to highly compensated employees. The amount of benefits provided as a percentage of compensation must be the same at the top and bottom of the pay scale.33 If an organization provides unequal benefits for high-paid and low-paid employees, the benefits will not qualify as tax-exempt compensation, which significantly reduces the value of the benefits. A benefit plan that meets the regulations necessary for tax exemption status is thus known as a qualified benefit plan.

Qualified benefit plan

A benefit plan that meets federal guidelines so that the organization can provide nontaxable benefits to employees.

Figure 12.2 Percentage of Workers Receiving Discretionary Benefits.

Supplemental Insurance

Many employers supplement required benefits with additional types of insurance. The most common supplement is life insurance, which is provided to over 50 percent of workers. Life insurance pays benefits to families or other beneficiaries when the insured individual dies. Another common supplement is disability insurance, which provides benefits to individuals who have physical or mental disabilities that prevent them from being able to work. In most cases, disability insurance pays approximately 60 percent of the person's typical wages.

Life insurance

A form of insurance that pays benefits to family members or other beneficiaries when an insured person dies.

Disability insurance

A form of insurance that provides benefits to individuals who develop mental or physical conditions that prevent them from working.

Retirement Savings

The legally required benefit of social security provides a minimum level of savings for all employees. However, the amount received from social security is not sufficient for most retirees. Many organizations thus supplement the required social security benefit with a discretionary retirement savings plan. Retirement saving programs can be placed into two broad categories: defined benefit plans and defined contribution plans.

A defined benefit plan guarantees that when employees retire, they will receive a certain level of income based on factors such as their salary and the number of years they worked for the organization. For instance, an employee who retires after 25 years with the company and who had an average annual salary of $100,000 over the final five years of employment might receive a monthly payment of $2,500. Employees must usually work for the organization for a period of time, such as five years, before they are eligible to participate in the defined benefit program. When they become eligible, they are said to be vested. With a defined benefit plan, risk is assumed by the organization. In essence, the organization defines a guaranteed level of monthly payment and then bears the burden of figuring out how to pay it. On the one hand, the predictability of these benefits is an advantage for employees. On the other hand, the fact that the benefits remain constant is also a disadvantage. Retirement income is fixed even though inflation may increase the cost of living. Today, about 25 percent of employees participate in defined benefit plans.34

Defined benefit plan

A retirement plan under which an organization provides retired individuals with a fixed amount of money each month; the amount is usually based on number of years employed and pay level at retirement.

Vested

Eligible to receive the benefits of a retirement plan; individual employees must often work a certain period of time before such eligibility is granted.

The second type of voluntary retirement program is a defined contribution plan. Here, the organization pays a certain amount each month into a retirement savings account for each employee. The amount contributed each month during the worker's career is fixed, or defined. The amount an employee receives upon retirement is not fixed, however; it depends on how the money is invested. Investment decisions, such as which particular stocks and bonds to purchase, are made by individual employees. From the organization's perspective, defined contribution plans shift risk to employees. The organization pays a certain amount into the retirement fund but is not obligated to provide a certain level of income during retirement. Low return rates for investments become the employee's problem. In addition, defined contribution plans require much less paperwork than defined benefit plans. These factors make defined contribution plans more common than defined benefit plans. Nearly 90 percent of organizations with more than 100 employees offer defined contribution plans, and over 40 percent of all employees participate in such plans.35

Defined contribution plan

A retirement plan under which the employer and/or the employee contribute to a fund for which only the contributions are defined and benefits vary according to the amount accumulated in the fund at retirement.

A common form of defined contribution plan is the 401(k), which is named after Section 401(k) of the federal tax code. The 401(k) plan allows employees to set up personal savings accounts to which they make tax-deferred contributions. In most cases, the organization matches employee contributions to the plan. For instance, an employee may invest 3 percent in the savings account, which is matched by the organization providing another 3 percent. The individual decides how to invest the money in the account, and the account grows until retirement. Taxes are paid when money is taken from the account after retirement. As mentioned, this sort of plan places the burden of investment with individual employees. Employees who are willing to put money in riskier investments have the potential to earn higher rates of return. Of course, they also bear the risk of losing a substantial amount of their savings. Thus, employees who participate in defined contribution plans must become more educated about investment decisions. Perhaps the most important lesson for employees is not to invest all their retirement savings in the stock of their employer. Unfortunately, many workers—such as the thousands of Enron employees whose retirement savings were lost when the company went bankrupt—have learned this lesson the hard way.

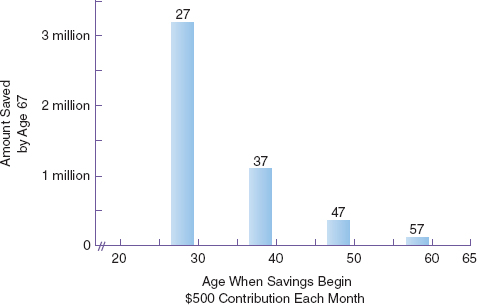

Young workers often make the mistake of not investing in retirement funds if they are not required to do so. They have a mistaken belief that they can delay retirement savings. However, Figure 12.3 shows that the sooner you start investing in retirement, the better off you will be. Money invested early earns interest for many more years, and the more interest it earns, the faster it grows.

Defined benefit and defined contribution plans result in different perceptions of attachment to an organization. Defined contribution plans are highly portable. The employee owns the account, and in most cases leaving an organization has very little impact on the employee's retirement savings. In contrast, defined benefit plans are associated with a particular employer, and savings are not portable. Employees often have to work for a certain period of time before they are eligible for the benefit. These plans are generally structured to reward people who stay with the organization for a long period of time. Although there is a general trend away from defined benefit programs, they make the most sense for organizations with Loyal Soldier and Committed Expert HR strategies.

Figure 12.3 Accrual of Retirement Benefits.

Pay Without Work

Pay without work is the most common employee benefit. It involves paying employees as if they worked during a certain period—for example, holidays and vacations—even though they were not actually working. Over 70 percent of employees receive paid holidays and vacations.36 The number of paid holidays and vacations generally increases with time in the organization, which makes pay without work an important motivator for organizations with Loyal Soldier and Committed Expert HR strategies. Most organizations also provide sick leave, which allows employees to receive pay when they cannot work because of illness. In most cases, employees can accrue, or build up, sick leave based on their length of time with the organization. In order to encourage employees not to take sick leave when they do not need it, organizations often allow employees to accrue sick leave over a number of years and to use this accrued sick leave as part of their retirement benefits.

Pay without work

Compensation paid for time off, such as holidays.

Sick leave

Compensation paid to employees who are unable to work because they are ill.

Lifestyle Benefits

Most of the benefits we have discussed so far focus on money. But money is not the most important consideration for many employees. Younger workers in particular are interested in working for organizations that fit their lifestyles. Important lifestyle considerations include being able to do enjoyable work and balancing work responsibilities with other aspects of life, such as family and leisure time. Some organizations emphasize benefits that enhance employees' lifestyles. As described in the “Building Strength Through HR” feature, Burton Snowboards also focuses on lifestyle benefits. Working for Burton is about more than simply earning money. Other common lifestyle benefits include such diverse things as tuition for advanced education, help with weight management classes, grocery shopping, party planning, and flexible schedules.37

FLEXIBLE BENEFIT PROGRAMS

Of course, not every employee values the same benefits. A father with young children may be most interested in comprehensive health insurance. A middle-aged woman may want additional retirement benefits. A young single worker might prefer additional vacation time for travel. A reward package that provides the same benefits to every employee fails to optimize the value of compensation expenditures. A potential solution is a flexible benefit program, which allows each employee to choose customized benefits from a menu of options. These benefits are sometimes known as cafeteria benefits.

Flexible benefit program, or cafeteria benefits

A benefit program that allows employees to choose the benefits they want from a list of available benefits.

Most flexible benefit programs provide each employee with an account of dollar credits. A dollar cost is associated with each benefit. Health insurance might have a value of $400 per month, for example, and dental insurance might have a value of $75. Each employee then uses the allocated dollar credits to purchase benefits he or she wants. Dollars that are not spent cannot be taken as cash, so each employee is encouraged to spend the total allocation. Employees who spend more than their allotment have the extra amount deducted from their wage and salary earnings.

Employees often prefer flexible benefit programs over traditional benefit packages. When the global real estate advisory firm DTZ offered flexible benefits in England, for example, almost half of the 2,000 staff members chose to adjust their benefits. Providing flexible benefits has decreased employee turnover at DTZ.38 This effect is consistent with other research that shows an increase in employee satisfaction to be associated with flexible benefits.39 Flexible programs thus provide a strategic method for customizing benefits to maximize the value of benefits for each employee.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4

What Are Common Individual Incentives?

In addition to base pay, most organizations offer at least some incentives to reward high performers. These incentives can be provided to groups or to individuals. In this section, we examine incentives for individual workers. Individual incentives are something almost everyone experiences at a very early age. Clean your room and you can go outside to play. Eat your carrots and you can have a cookie. Don't run in the store and you can get a new toy. These are common incentives that many parents use to motivate the behavior of children.

Rewards in organizations are similar in many ways. Complete the project on time and you will get a bonus. Cooperate with coworkers and you will get a pay raise. Close the sale and you will receive a hefty commission. Each of these incentives is based on personal performance. Individuals who perform the required actions, or obtain the desired outcomes, are rewarded. To be effective, individual incentives should place a portion of compensation at risk and make those rewards dependent on performance, which is consistent with the motivational principle of contingency that we discussed in Chapter 11. Properly designed individual incentives also conform to the notion of line of sight by linking rewards to actions and outcomes that employees believe they can influence. Common individual incentives include piece-rate incentives, commissions, merit pay increases, and merit bonuses.

PIECE-RATE INCENTIVES

Imagine you have been hired to install car stereos. A basic compensation plan might pay you an hourly rate. You would receive the hourly wage regardless of the number of stereos installed. None of your pay would be at risk. Another compensation option is to pay you a set amount for each stereo you install. If you install zero stereos, you earn nothing. All of your pay is at risk. This second option is an example of a piece-rate incentive, where employees are paid a fixed amount for each piece of output they produce.

Piece-rate incentive

An individual incentive program in which each employee is paid a certain amount for each piece of output.

Perhaps the most famous example of an effective piece-rate system is Lincoln Electric. Lincoln manufactures and sells welding equipment. Most employees are paid on a piece-rate system. Each job is rated on skill, required effort, and responsibility. The company then assigns a base wage to each job. The base wage is the target compensation for the job, and it is set to be competitive with similar jobs in other organizations located in the same geographic area. Time studies are conducted to determine how many units an average person in each job can produce in an hour. The average number of units produced in an hour is called the standard rate. Employees are paid for each unit they produce, so an employee who produces the standard rate of units receives the equivalent of the base wage. An employee who produces more than the standard rate receives the equivalent of a higher hourly wage. An employee who produces fewer units receives the equivalent of a lower hourly wage. Pay is thus contingent on the number of units produced.40

Base wage

Target compensation for a job, which is determined in comparison to the wage that similar employees are being paid by other organizations.

Standard rate

The rate of pay that an employee receives for producing an average number of output units.

Piece-rate incentive systems can be powerful motivators. There is a strong pay-for-performance link. In fact, the strength of motivation with piece-rate systems can sometimes create problems. The strong incentive focuses employees' attention and effort on the actions that are rewarded, which means that other important tasks might not get done. Workers may neglect safety practices, for example, and may work so fast that they produce goods of inferior quality. A number of years ago, a national automobile repair chain learned about another potential negative effect of piece-rate incentives. Mechanics were paid a fixed amount for each repair they made. Motivation increased. However, some mechanics also began to recommend repairs that were not really needed. The end result was negative publicity that significantly harmed the repair chain's reputation.

Setting appropriate standards for the base wage rate and standard production rate is difficult. Problems arise when managers and employees disagree about the assumptions used to determine the appropriate standards. In some instances, workers deliberately work slowly when they know the standard rate is being computed. This allows them to easily produce at a rate higher than the standard rate once it has been set. In other instances, companies raise the standard rate when they feel that workers are exceeding the standard rate too much. Such practices destroy trust between managers and employees and often result in decreased motivation.41

Piece-rate incentive systems are most effective when the line of sight is such that an individual has sole responsibility for producing a measurable portion of a good or service. This is true at Lincoln Electric, mentioned earlier, where each worker can be given responsibility for a specific component of the overall machine. This clear identification of inputs allows Lincoln not only to clearly establish pay rates but also to track quality defects. Quality problems can be traced to individuals, who must fix the problems without additional pay. These conditions—clearly identifiable work and clear, objective performance measures—are often present in manufacturing facilities that pursue low-cost strategies. Piece-rate incentive systems are therefore most often observed in organizations with either Bargain Laborer or Loyal Solider HR strategies.

COMMISSIONS

Commissions represent a special form of piece-rate compensation that is most often associated with sales. For each sale obtained, a commission, or percentage of the total amount received, is paid to the salesperson. Commission rates range from up to 50 percent of the sales total for things like novelty goods to 3 percent for real estate. With a straight commission system, sales representatives are only paid when they generate sales. Alternatively, sales representatives may earn a base salary plus commissions.

Commission

An individual incentive program in which each employee is paid a percentage of the sales revenue that he or she generates.

From the organization's point of view, commissions offer several advantages. For one thing, they shift some of the risk associated with low sales from the organization to employees. Another advantage comes from the type of person who is attracted to a position with commission pay. People who are aggressive tend to favor commission-based pay, and these are the very people who excel as sales representatives.42 Commission incentives present potential disadvantages as well. One problem is that people who are paid commissions may tend to think of themselves as free agents with little loyalty to the organization. Turnover can be high if alternative sales jobs are available. Additional problems can arise if the desire to earn commissions drives sales representatives to focus on short-term results. Effort over a number of months to obtain a new account may not be immediately rewarded, which may negatively impact long-term results. Sales representatives paid with commissions may also be unwilling to perform activities that do not directly increase sales. From the individual sales representative's perspective, a straight commission system can also present difficulties because income is uneven. Take-home pay can be very high in one month but virtually zero in the next month. Another potential problem is complexity of calculations, which is discussed in the “Technology in HR” feature.

From the employee's point of view, a major advantage of commissions is the fact that the overall level of compensation is usually higher with commissions than with salary. Consistent with agency theory, the employee receives greater rewards for assuming more of the risk of low sales.

One common approach is to combine commissions with a low base salary. The low base salary provides a safety net so that employees such as sales representatives can cover their living expenses when sales are low. This reduces some of the risk. The base compensation is not, however, high enough to sustain their normal standard of living, which provides a strong incentive to perform at a higher level. Because commission-based compensation plans have the effect of creating pay systems where some people receive much higher pay than others, they tend to be most appropriate for organizations that adopt Free Agent and Committed Expert HR strategies.

MERIT PAY INCREASES

Many employees, including university professors, expect an annual pay raise. One purpose of the annual pay raise is to ensure that an individual's salary keeps pace with inflation. The cost of living generally increases each year, and a salary increase is needed so that employees are able to maintain their standard of living. In most organizations, though, employees do not receive equivalent raises. Some receive higher raises than others. Most annual raises contain a merit pay increase, which represents an increase in base salary or hourly rate that is linked to performance. Merit pay increases reward employees for ongoing individual contributions. As explained in the “How Do We Know?” feature, there are many potential biases that can create compensation problems.

Merit pay increase

An individual incentive program in which an employee's salary increase is based on performance.

Research suggests that organizations that provide merit pay increases do indeed have higher productivity.43 Yet, if a reward is going to result in high motivation, it must be seen as being based on performance. This means that merit pay increases work best when there are clear and accurate methods for assessing performance. A prerequisite for merit pay is thus a high-quality performance assessment based on the principles discussed in Chapter 8. Performance assessment and compensation are thus specific practices that can work together to create an overall effective approach for human resource management. Indeed, linking raises to performance is critical for merit systems because employees have been found to be happier with their pay raises when they perceive that the raise is a result of their high contribution.44

Small differences among merit increases are another concern associated with merit pay increases. The principle of valence, which was discussed in Chapter 11, suggests that people are motivated only if they value the reward being offered. In many organizations, the merit pay increase for a high performer may be only 1 percent higher than the increases for average performers. To be truly motivational, the merit increase needs to be in the 5 to 10 percent range.45 Unless there is adequate funding to provide meaningful raises, the difference between a high raise and a low raise may simply not have enough valence to motivate higher performance. In the end, small raises can result in little incentive for people receiving a comfortable salary to continue providing maximum contributions to the organization.

An organization's overall human resource strategy is also important in determining the value of merit pay increases. Merit pay increases are designed to recognize ongoing contributions to an organization. Workers become eligible for a pay increase each year they stay employed. Merit pay increases are thus a longterm incentive designed to reward employees who continue to provide quality inputs over extended periods of time. This means that merit pay increase incentives are most common in organizations with a Committed Expert HR strategy.

MERIT BONUSES

A merit bonus is a sum of money given to an employee in addition to normal wages. It differs from a merit increase in that a merit pay increase becomes part of the base pay for the next year, whereas a merit bonus does not. In many cases, merit bonuses are given on a fixed schedule, such as at the end of the year. In other cases, bonuses are unplanned and given when high performance is observed. In either case, as you might expect from the discussion of merit pay increases, motivation is maximized when the bonus is clearly tied to specific behaviors and outcomes.

Merit bonus

A one-time payment made to an individual for high performance.

Merit bonuses present a potentially useful alternative to merit pay increases. Think once again of the professor example. Instead of providing an annual salary increase, a university might decide to provide an annual bonus. Now, instead of receiving a salary increase that is guaranteed for future years, the professor will need to earn the bonus again each year. Such an arrangement places more of the salary at risk and clearly communicates an expectation for ongoing high performance.

Current trends suggest that merit bonuses are taking the place of merit raises in more and more organizations. Over the past 10 years, employers have tended to offer slightly lower bonuses, but the number of employees receiving bonuses has increased. For instance, Whirlpool Corporation, which makes household appliances, recently overhauled its entire pay-for-performance system to increase the emphasis on bonuses and decrease the emphasis on raises. Such systems are designed to strengthen perceptions that pay truly depends on performance, which in turn increases motivation.46

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 5

What Are Common Group and Organizational Incentives?

Most of us are familiar with group incentives. Think of siblings who are taken out to share a pizza when they work together to clean the house. How about members of a football team who must all run extra sprints because someone makes a mistake? Rewards in many organizations are similarly based on shared behaviors and outcomes.

As described in Chapter 4, work is increasingly being structured around teams rather than individuals. Because providing individual incentives often destroys teamwork, organizations are adopting group-based incentives at an increasing pace. Common group-based incentives include team bonuses and gain-sharing plans. Most businesses also use organizational incentives to encourage employees to develop a sense of ownership in the organization. Common organizational incentives include profit sharing and stock plans.

TEAM BONUSES AND INCENTIVES

In many ways, team incentives are similar to individual incentives. The main difference is that team incentives are linked to the collective performance of groups rather than to the performance of individuals. Rewards are given when the group as a whole demonstrates high performance. Team rewards work best when the size of the group being measured is relatively small, when collective performance can be accurately measured, and when management support for the program is high.47

One type of group incentive is the goal-based team reward, which provides a payment when a team reaches a specific goal. Following the principles of goal-setting theory that was introduced in Chapter 11, an incentive of this kind provides a team with a specific objective and rewards the team if the objective is achieved. Goal-based team rewards are thus a type of contract in which the organization agrees to provide a reward if the team meets a specific performance objective. Another type of team incentive is the discretionary team bonus, which provides payment when high performance is observed. With discretionary rewards, no goal is set to achieve a specific outcome. Managers simply provide a reward whenever they think the team has performed well. The frequency and size of the reward are at the discretion of the manager.48

Goal-based team reward

A group-level incentive provided to members of a team when the team meets or exceeds a specific goal.

Discretionary team bonus

A group-level incentive provided to members of a team when a supervisor observes high collective performance.

When an award is given to a team, it can be divided among individual team members in two basic ways. One way is to divide it equally among team members. The other is to use some form of individual evaluation and provide higher-performing members with a greater portion of the reward. Each method of division has strengths and weaknesses.49 Giving team members equal shares of the reward builds a sense of unity and teamwork. Indeed, equal allocation among team members seems to be the most common way of dividing team bonuses.50 This allocation may, however, fail to motivate individuals to put forth their best effort. In contrast, dividing the reward based on performance recognizes high-achieving individuals but may undermine cooperative effort. Determining which individuals are top performers is also difficult. In some cases, team members provide peer assessments. In other cases, an outside observer, such as the supervisor, allocates the bonus. Regardless of who makes the allocation, an accurate appraisal of individual performance is essential when team rewards are divided equally. At any rate, as explained in the “Building Strength Through HR” feature, moving to team incentives often results in performance improvement.

Organizations can also reward employees for the contributions they make to teams. Rather than basing the reward on team performance, this method provides individual incentives for team contribution. In essence, then, this is an individual incentive specifically for people who offer valuable inputs to teams. Team members are rated on scales that measure their contributions to the team, and higher rewards are given to the highest-rated members. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Huntsville Center surveyed its employees and found strong support for this approach, which encourages both teamwork and individual effort.51

GAINSHARING

Who should reap the benefits when an organization reduces costs and increases production? One answer might be managers and owners. This seems reasonable if managers and owners are responsible for the improvements. But what happens if regular employees take the primary responsibility for improvement? Shouldn't these employees receive some of the reward? The question of sharing financial gains among owners, managers, and regular employees is the central issue of gainsharing. Gainsharing occurs when groups of workers receive a portion of the financial return from reducing costs and improving productivity. In essence, gainsharing aligns the interests of workers with the interests of company owners.52

Gainsharing

A group-level incentive program that rewards groups of employees for working together to reduce costs and improve productivity.

As many as 26 percent of U.S. companies use some form of gainsharing.53 The practice is particularly common in manufacturing organizations, where costs and productivity gains can be objectively measured.54 In its most basic form, gainsharing establishes a benchmark for productivity. For instance, a tire manufacturer may examine current records and determine that producing a particular tire costs $50. Once this cost has been established, the organization then agrees to share any future cost savings beyond $50 per tire with employees who are part of the manufacturing team. Limiting the gainsharing plan to only those employees who have a direct influence on the particular product is important for maintaining line of sight. After the gainsharing plan has been developed, employees become involved in a participative effort to make production more efficient. In the case of tire production, employees might work together by focusing on such things as reducing the number of defective tires, redesigning work processes, or simply working faster. If the process becomes more efficient, the amount of money saved is split between the organization and employees. A 50–50 split is common.

An example of a gainsharing plan is the compensation practice of a Verizon unit that produces telephone directories. Standards for budgets and production costs are established, and savings are split between the company and employees. Forty-five percent is reinvested in the general funds of the company. Ten percent is placed in an improvement fund specifically targeted for training, equipment, and other improvements that directly advance the telephone directory production process. Thirty-five percent is given back to employees in a quarterly payout. This payout is adjusted for quality of output; it is increased if quality is high and decreased if quality is low and corrections are required. The remaining 10 percent of the gain is saved in a reserve fund that is shared with employees a year later when costs resulting from customers' claims of printing errors in the directories have been determined.55

Healthcare is a particular field that has shown increased interest in gainsharing in recent years. The costs of healthcare have been rising at a growing rate, and hospitals have begun to contract to share cost savings with physicians. Initially, the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services argued that such arrangements violated Medicare policies that guard against limiting services to patients. It was thought that offering physicians an incentive to reduce costs would result in lower quality of care. However, more recent decisions from the Office of Inspector General have allowed gainsharing.56 One example of successful gainsharing in a health setting is PinnacleHealth, a five-hospital system based in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The gainsharing program at PinnacleHealth encouraged cardiac surgeons to reduce costs through standardizing supplies. The total savings amounted to $1 million, half of which was shared with the surgeons.57

Source: Information from Matthew H. Roy and Sanjiv S. Dugal, “Using Employee Gainsharing Plans to Improve Organizational Effectiveness,” Benchmarking 12 (2005): 250–259.

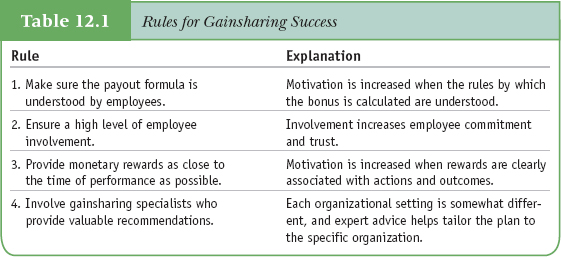

Like other forms of incentive compensation, gainsharing is not equally effective for all organizations. Table 12.1 provides a list of issues that increase the likelihood of success for gainsharing programs. In general, gainsharing requires a great deal of cooperation and trust between managers and employees. Chances of success increase when employees are highly involved in developing and carrying out the plan. This makes gainsharing most beneficial in organizations where employees expect to have long careers. Given that gainsharing most frequently occurs in manufacturing settings emphasizing cost reduction, organizations pursuing Loyal Soldier HR strategies seem to be best suited for this type of group incentive.

PROFIT SHARING

Profit sharing occurs when employees receive incentive payments based on overall organizational profits. As many as 70 percent of Fortune 1000 companies participate in some form of profit sharing.58 In most profit-sharing plans, the publicly reported earnings of an organization are shared with employees. Some organizations share the reward when the profit is reported, whereas others defer payment so that employees receive a share of the profit only if they remain employed for a number of years.

Profit sharing

An organization-wide incentive program under which a portion of organizational profits are shared with employees.

Earlier, we discussed the piece-rate incentives offered by Lincoln Electric. The company also places a large portion—frequently more than half—of company profits in a bonus pool that is shared with employees.59 Every employee receives a portion of the bonus, but the size of each employee's portion depends in part on individual performance evaluations collected twice each year. In many instances, bonuses at Lincoln Electric can be as much as 50 percent of the piece-rate total.60

Profit sharing has the potential to align the interests of employees with the interests of owners. However, a major problem with profit sharing is line of sight. In many organizations, employees simply don't feel that their personal efforts will have an impact on organizational profits. This lack of a perceived link between personal effort and compensation means that profit sharing may not be a strong motivator for average employees. Another potential weakness of profit sharing is that employees come to expect bonuses and are dissatisfied in years when no bonus is available. Employees often express dissatisfaction in years when productivity is down and the bonus is not available. Many do not believe it is fair for their bonuses to be reduced by poor market conditions.61

Even though it has limitations, profit sharing can be an important part of an overall compensation package. Sharing profits with employees provides a strong motivator when employees perceive that their individual efforts truly influence overall profits. What about the issue of fit with the organization's human resource strategy? Here, the main concern is the timing of the profit-sharing payout. For organizations pursuing a Free Agent HR strategy, the payout should be made frequently. For organizations pursuing Committed Expert and Loyal Soldier HR strategies, it may make sense to delay the payout as part of a retirement package that builds a long-term bond with employees.

STOCK PLANS

One way to align the interests of employees and owners is by making employees owners. In corporations, this can be done through stock ownership. Stock plans transfer corporate stock to individual employees. In some cases, shares of stock are given directly to employees. However, most organizations instead provide stock options, which represent the right to buy company stock at a given price on a future date. Most stock options are granted at current stock prices. This means that the stock option has no value unless the stock price increases; after all, anyone can buy the stock at the current price. If the stock price does increase, an employee can buy the stock at the option price and reap a substantial reward. However, if the value of the stock falls below the option price, the employee can simply choose not to purchase the stock. This set of circumstances provides a long-term incentive that links an individual's financial interests with the financial interests of others who own stock.

Stock plan

An incentive plan that gives employees company stock, providing the employees with an ownership interest in the organization.

Stock options

Rights to purchase stock at a specified price in the future.

A number of years ago, stock options were primarily reserved for top executives. However, a majority of Fortune 1000 companies, including PepsiCo and Procter & Gamble, now provide stock plans for regular employees.62 Top-performing small companies also provide employees with stock plans. For instance, Kyphon—a medical device manufacturer located in Sunnyvale, California—provides its 535 employees with stock options and a 15 percent discount on additional stock purchases. This incentive has helped the company to become known as one of the 25 best medium-sized companies to work for in the United States and has also been credited with helping to produce a 63 percent annual increase in sales.63

In addition to stock options, many organizations offer employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), in which the organization contributes stock shares to a tax-exempt trust that holds and manages the stock for employees. One advantage of ESOPs is favorable tax status, since organizations are allowed to exclude the portion of stock given to employees from taxation.

Employee stock ownership plan (ESOP)

A plan under which an organization sets up a trust fund to hold and manage company stock given to employees.

Although stock plans are increasingly popular and some evidence links their use to improved organizational performance, the extent to which they are effective in actually motivating individual employees is frequenlty questioned. As with profit sharing, an employee's line of sight is often far removed from the organization's stock price. Even though CEOs and other top executives may have a clear line of sight in this area, most employees are not likely to perceive that their efforts actually influence stock prices. Stock plans are thus not expected to increase motivation for most employees.

Stock plans have other potential problems. In some instances, CEOs have been found to manipulate earnings in order to maximize their personal stock return.64 Although widely accepted in the United States, stock plans have also met with resistance in other countries such as Germany.65 From employees' point of view, a potential weakness of stock plans is that employees may have most of their financial investments tied up in the stock of a single company—the one that employs them. Much of their financial security depends on the performance of this company. If the company's stock performs poorly, their financial investments, such as retirement savings, can quickly disappear.