How Can Strategic Employee Selection Improve an Organization?

Employee selection is the process of choosing people to bring into an organization. Effective selection provides many benefits. Selecting the right employees can improve the effectiveness of other human resource practices and prevent numerous problems. For instance, hiring highly motivated employees who fit with the organizational culture can reduce disciplinary problems and diminish costs related to replacing employees who quit. Such benefits help explain why organizations that use effective staffing practices have higher annual profit and faster growth of profit.1 In short, a strategic approach to selecting employees can help an organization obtain and keep the talent necessary to produce goods and services that exceed the expectations of customers.

Employee selection

The process of testing and gathering information to decide whom to hire.

One organization that expends a lot of effort on selection is the military. Each year, the United States Marine Corps selects and trains over 38,000 people. Of course, not everyone who wants to become a marine is accepted into the Corps. Before being accepted and enduring training at either the San Diego, California, or Parris Island, South Carolina, location, recruits must pass both mental and physical examinations.2

Because marines are required to make sound decisions quickly, the Marine Corps bases part of its selection decisions on scores for a mental ability test. This examination is known as Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB). The test consists of 225 multiple-choice questions in the areas of General Science, Arithmetic Reasoning, Word Knowledge, Paragraph Comprehension, Mathematics Knowledge, Electronic Information, Auto and Shop Information, Mechanical Comprehension, and Assembling Objects. Test results determine not only whether someone will be admitted to the Marine Corps but also what type of occupations can be pursued once basic training is complete. For example, it takes a higher score to become an aerial navigator than it does to become a combat photographer.3

Given that the job also requires physical fitness, recruits must additionally pass an assessment known as the Initial Strength Test (IST). The test for men requires pull-ups, crunches, and a timed run. For women the test has historically required a flex armed hang in place of pull-ups, but test administrators are discussing whether they should require female recruits to demonstrate pull-ups the same as male recruits. This shift parallels the recent change to allow female marines into combat units.4

Physical testing does not, however, end once someone is accepted into the Marine Corps. Each year a marine must complete an evaluation known as the Physical Fitness Test (PFT), which is similar to the IST. Each marine must also complete an annual Combat Fitness Test (CFT), which includes completing a timed endurance test, a lifting exercise, and an obstacle course requiring activities such as crawling, carrying, and throwing.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

How Is Employee Selection Strategic?

As we can see from the Marine Corps example, hiring the right employees often takes a great deal of planning. An organization's employee selection practices are strategic when they ensure that the right people are in the right places at the right times. This means that good selection practices must fit with an organization's overall HR strategy. As described in Chapter 2, HR strategies vary along two dimensions: whether they have an internal or an external labor orientation and whether they compete through cost or differentiation. These overall HR strategies provide important guidance about the type of employee selection practices that will be most effective for a particular organization.

ALIGNING TALENT AND HR STRATEGY

Consistent with the overall HR strategies, strategic selection decisions are based on two important dimensions. One dimension represents differences in the type of talent sought. At one end of the continuum is generalist talent—employees who may be excellent workers but who do not have particular areas of expertise or specialization. At the other end of the continuum is specialist talent—employees with specific and somewhat rare skills and abilities.6

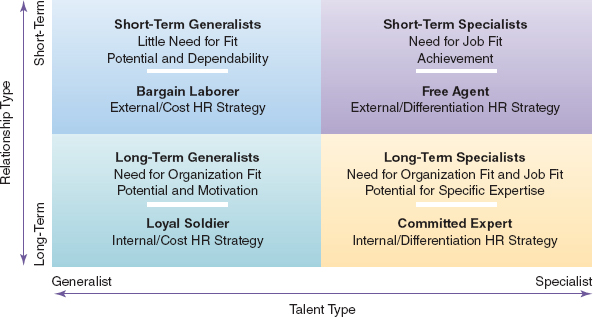

Figure 6.1 Strategic Framework for Employee Selection.

Another dimension represents the type of relationship between the employees and the organization. At one end of the continuum is long-term talent. Employees in this category stay with the organization for a long time and develop a deep understanding of company practices and operations. At the other end of the continuum is short-term talent. These employees move from organization to organization without developing expertise in how things are done at any particular place.7 Combining the two dimensions yields four general categories shown in Figure 6.1: short-term generalist talent, long-term generalist talent, long-term specialist talent, and short-term specialist talent. Next, we look at each of these categories in turn and consider how they fit with the HR strategies introduced in Chapter 2.

Short-Term Generalists

If you were hired to work at a drive-in restaurant, you would not need specialized skills, you would not earn high wages, and you probably would not keep the job for a very long time. Fast-food workers are short-term generalists, who provide a variety of different inputs but do not have areas of special skill or ability. Other examples include some retail sales clerks and hotel house-keepers. Short-term generalist talent is associated with the Bargain Laborer HR strategy.8 Organizations with this HR strategy fill most positions by hiring people just entering the workforce or people already working in similar jobs at other companies. Selection has the objective of identifying and hiring employees to produce low-cost goods and services, and selection decisions are based on identifying people who can perform simple tasks that require little specialized skill.

Short-term generalists

Workers hired to produce general labor inputs for a relatively short period of time.

Hiring generalists can be beneficial because people without specialized skills do not generally demand high compensation, which keeps payroll costs as low as possible. Because generalists lack specific expertise, they also are usually more willing to work in routine jobs and do whatever they are asked.

Long-Term Generalists

If you were to take a job working for an electricity provider, you might not need specialized skills, but you would most likely plan to remain with the organization for a long career. People working for utility companies are often longterm generalists who do not have technical expertise but who develop skills and knowledge concerning how things are done in a specific organization. Other common examples of long-term generalists are people who work for government agencies and for some package delivery companies. These workers contribute in a number of areas but do not need specific technical skills and abilities. Long-term generalists are beneficial for organizations using the Loyal Soldier HR strategy.9 Organizations with this HR strategy focus on keeping employees once they are hired. Staffing still has the objective of hiring employees to produce low-cost goods and services, but a stronger commitment is formed, and efforts are made to identify people who will remain with the organization for a long time.

Long-term generalists

Workers hired to perform a variety of different jobs over a relatively long period of time.

The generalist's lack of specific expertise allows firms to reduce payroll costs. However, over time employees develop skills and abilities that are only valuable to the specific organization, which reduces the likelihood that they will move to another employer. People develop relationships and form a strong sense of commitment to the organization.

Long-Term Specialists

Suppose you took a job as an accountant with a large firm that makes and sells consumer goods such as diapers and cleaning products. People doing this job are most often long-term specialists who develop deep expertise in a particular area. Pharmaceutical sales representatives and research scientists are commonly employed as long-term specialists. People in these jobs are expected to develop specialized skills and stay with the organization for a long time. The use of longterm specialists fits the Committed Expert HR strategy.10 Organizations that use this HR strategy develop their own talent. Selection has the objective of identifying people capable of developing expertise in a particular area so they can innovate and produce superior goods and services over time.

Long-term specialists

Workers hired to develop specific expertise and establish a lengthy career within an organization.

Hiring people who can develop specialized skills over time enables organizations to create and keep a unique resource of talent that other organizations do not have. Employees are given the time and assets to develop the skills they need to be the best at what they do.

Short-Term Specialists

Information technology specialists often work as short-term specialists—employees who provide specific inputs for relatively short periods of time. These workers are valuable for organizations using the Free Agent HR strategy.11 Organizations with this HR strategy hire people away from other organizations. Staffing is aimed at hiring people who will bring new skills and produce innovative goods and top-quality service. Selection decisions focus on identifying people who have already developed specific skills. Other examples of this type of talent include investment bankers and advertising executives.

Short-term specialists

Workers hired to provide specific labor inputs for a relatively short period of time.

Hiring short-term specialists allows firms to quickly acquire needed expertise. New hires bring unique knowledge and skills to the organization. The organization pays a relatively high price for such knowledge and skills but makes no long-term commitments.

MAKING STRATEGIC SELECTION DECISIONS

Another way to examine how organizations make employee selection decisions focuses on two primary factors: the balance between job-based fit and organization-based fit and the balance between achievement and potential. As you can see in Figure 6.1, both factors relate clearly to the talent categories just discussed.

Balancing Job Fit and Organization Fit

The first area of balance concerns whether employees should be chosen to fit in specific jobs or to fit more generally with the organization. When job-based fit is the goal, the organization seeks to match an individual's abilities and interests with the demands of a specific job. This type of fit is highly dependent on a person's technical skills. For instance, high ability in mathematics results in fit for a job such as financial analyst or accountant. In contrast, organization-based fit is concerned with how well the individual's characteristics match the broader culture, values, and norms of the firm. Organization-based fit depends less on technical skills than on an individual's personality, values, and goals.12 A person with conservative values, for example, might fit well in a company culture of caution and tradition. Employees who fit with their organizations have higher job satisfaction, and better fit with the organization has been shown to lead to higher performance in many settings.13 As described in the “How Do We Know?” feature, the HR strategy has an impact on how job and organization fit are weighted.

Job-based fit

Matching an employee's knowledge and skills to the tasks associated with a specific job.

Organization-based fit

Matching an employee's characteristics to the general culture of the organization.

As suggested earlier, we can combine the concept of fit with the talent-based categories discussed earlier. In general, job-based fit is more important in organizations that seek to hire specialists than in those that seek generalists. Similarly, organization-based fit is more important for long-term than for short-term employees. These differences provide strategic direction for employee selection practices.

Organizations pursuing Bargain Laborer HR strategies are not highly concerned about either form of fit. Employees do not generally bring specific skills to the organization. Neither are they expected to stay long enough to necessitate close organizational fit. Thus, for firms pursuing a Bargain Laborer HR strategy, fit is not strategically critical, and hiring decisions tend to focus on obtaining the least expensive labor regardless of fit.

Organizations pursuing the Loyal Soldier HR strategy benefit from hiring employees who fit with the overall organization. Job-based fit is not critical. Employees rotate through a number of jobs, and success comes more from loyalty and high motivation than from specific skills. In contrast, lengthy expected careers make fit with the organization very important. Employee selection decisions in organizations with a Loyal Soldier HR strategy should thus focus primarily on assessing personality, values, and goals.

Organizations pursuing a Committed Expert HR strategy require both job-based fit and organization-based fit. Organization-based fit is necessary because employees need to work closely with other members of the organization throughout long careers. Job-based fit is necessary because employees are expected to develop expertise in a specific area. Even though new employees may not yet have developed specific job skills, general aptitude in the specialized field, such as accounting or engineering, is important. Selection decisions in firms pursuing Committed Expert HR strategies should thus be based on a combination of technical skills and personality, values, and goals.

Job-based fit is critical for organizations pursuing a Free Agent HR strategy. These organizations hire employees specifically to perform specialized tasks and expect them to bring required knowledge and skills with them. An employee's stay with the organization is expected to be relatively short, which means that fit with the organization is not critical. Selection decisions in organizations with a Free Agent HR strategy should thus focus primarily on assessing technical skills and abilities.

Balancing Achievement and Potential

The second area of balance concerns whether employees should be chosen because of what they have already achieved or because of their potential for future accomplishments. Assessments aimed at measuring achievement focus on history and past accomplishments that reveal information about acquired abilities and skills. For instance, a job applicant for an elementary school teaching position might have graduate degrees and years of experience that demonstrate teaching skills. In contrast, assessments aimed at measuring potential are future-oriented and seek to predict how a person will learn and develop knowledge and skill over time.14 In this case, an applicant for an elementary teaching position may just have graduated with high honors from a prestigious university, demonstrating high potential.

Achievement

A selection approach emphasizing existing skills and past accomplishments.

Potential

A selection approach emphasizing broad characteristics that foreshadow capability to develop future knowledge and skill.

Again, we can relate the choice between achievement and potential to the framework in Figure 6.1. Organizations that use Bargain Laborer HR strategies do not require highly developed skills.15 Measures of achievement are not required. For these organizations, selection methods assess potential by predicting whether applicants will be dependable and willing to carry out assigned tasks.

Hiring people based on potential is critical for organizations with longterm staffing strategies. These organizations provide a great deal of training, which suggests that people learn many skills after they are hired. With a Loyal Soldier HR strategy, selection measures should focus on ability, motivation, and willingness to work in a large variety of jobs. For a Committed Expert HR strategy, the focus is on assessing potential to become highly skilled in a particular area.

Organizations seeking short-term specialists focus on measuring achievement, because they seek employees who already have specific skills. Required skills change frequently, and a general lack of training by the organization makes it very difficult for these employees to keep up with new technologies. Hiring practices for organizations with Free Agent HR strategies thus focus on identifying individuals who have already obtained the necessary skills and who have demonstrated success in similar positions.

Gaining Competitive Advantage from Alignment

Of course, not all organizations have selection practices that are perfectly aligned with overall HR strategies. Some firms hire long-term generalists even though they have a Free Agent HR strategy. Other firms hire short-term specialists even though they have a Bargain Laborer HR strategy. The selection practices in such organizations are not strategic, and these organizations often fail to hire employees who can really help them achieve their goals. In short, organizations with closer alignment between their overall HR strategies and their specific selection practices tend to be more effective. They are successful because they develop a competitive advantage by identifying and hiring employees who fit their needs and strategic plans.16 What works for one organization may not work for another organization with a different competitive strategy. A key for effective staffing is thus to balance job fit and organization fit, as well as achievement and potential, in ways that align staffing practices with HR strategy.

What Makes a Selection Method Good?

We have considered strategic concerns in employee selection. The next step is to evaluate specific methods that help accomplish strategy. How can an organization go about identifying tests or measures that will identify people who fit or who have the appropriate mix of potential and achievement? Should prospective employees be given some type of paper-and-pencil test? Is a background check necessary? Will an interview be helpful? If so, what type of interview is best? Answers to the questions provide insights about the accuracy, cost effectiveness, fairness, and acceptability of various selection methods. Next, we examine a few principles related to each question. These principles include reliability, validity, utility, legality and fairness, and acceptability. Figure 6.2 illustrates basic questions associated with each principle.

RELIABILITY

Reliability is concerned with consistency of measurement. An example that illustrates this concept can be made by examining the selection of university athletes.

Reliability

An assessment of the degree to which a selection method yields consistent results.

Imagine that two coaches for a football team have just returned from separate recruiting trips. They are meeting to discuss the recruits they visited. The first coach describes a great recruit who weighs 300 pounds. The second coach reports about someone able to bench press 500 pounds. Which player should the coaches select? It is impossible to compare the recruits, since different information was obtained about each person. The measures are not reliable.

The football example may seem a bit ridiculous, but it is not much different from what happens in many organizations. Just think of the interview process. Suppose five different people interview a person for a job. In many organizations, the interviewers' judgments would not be consistent.

How, then, can we determine whether a selection method is reliable? One way to evaluate reliability is to test a person on two different occasions and then determine whether scores are similar across the two times. We call this the test-retest method of estimating reliability. Another way to evaluate reliability is to give two different forms of a test. Since both tests were designed to measure the same thing, we would expect people's scores to be similar. This is the alternate-forms method of estimating reliability. A similar method involves the use of a single test that is designed to be split into two halves that measure the same thing. The odd- and even-numbered questions might be written so that they are equivalent. We call this the split-halves method of estimating reliability. A final method, called the inter-rater method, involves having different raters provide evaluations and then determining whether the raters agree.

Test-retest method

A process of estimating reliability that compares scores on a single selection assessment obtained at different times.

Figure 6.2 What Makes a Selection Method Good?

Alternate-forms method

A process of estimating reliability that compares scores on different versions of a selection assessment.

Split-halves method

A process of estimating reliability that compares scores on two parts of a selection assessment.

Inter-rater method

A process of estimating reliability that compares assessment scores provided by different raters.

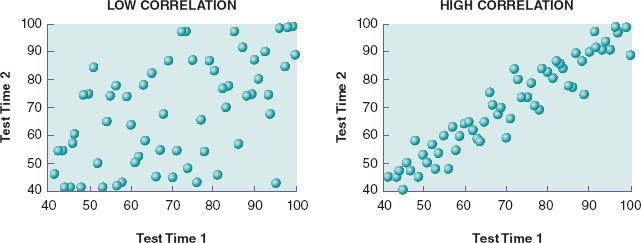

Each method of estimating reliability has its own strengths and weaknesses. However, all four methods rely on the correlation coefficient, a numerical indicator of the strength of the relationship between two sets of scores. Correlation coefficients range from a low of 0, which indicates no relationship, to a high of 1, which indicates a perfect relationship. Figure 6.3 provides an illustration of correlation coefficients. Two scores for each person are represented in the graph. The first score is plotted on the horizontal axis, and the second score is plotted on the vertical axis. Each person's two scores are thus represented by a dot. In the graph representing a low correlation, you can see that some people who did very well the first time did not do well the second time. Others improved a lot the second time. The scores are quite scattered, and it would be difficult to predict anyone's second score based on his or her first score. In the graph representing a high correlation, the scores begin to follow a straight line. In fact, scores with a correlation of 1 would plot as a single line where each person's second score could be predicted perfectly by his or her first score.

Correlation coefficient

A statistical measure that describes the strength of the relationship between two measures.

Correlation coefficients can also be negative (indicating that high scores on one measure are related to low scores on the other measure), but we do not generally observe negative correlations when assessing reliability. When it comes to reliability estimates, a higher correlation is always better. A correlation coefficient approaching 1 tells us that people who did well on one of the assessments generally did well on the other.

Just how high should a reliability estimate be? Of course, this depends on many different aspects of the assessment situation. Nevertheless, a good guideline is that a correlation coefficient of .85 or higher suggests adequate reliability for test-retest, alternate-forms, and split-halves estimates.17 Inter-rater reliability estimates are often lower because they incorporate subjective judgment, yet high estimates are still desirable.

Figure 6.3 Graphical Illustration of Correlations.

Knowing in general how high reliability estimates should be makes managers and human resource specialists better consumers of selection procedures. Consulting firms and people within an organization often propose many different selection methods. Important decisions must be made about which of the many possible methods to use. The first question to ask about any selection procedure is whether it is reliable. Information about reliability should be available from vendors who advocate and sell specific tests and interview methods.

VALIDITY

Once reliability has been established, we can turn to a selection method's validity. Suppose the football coaches in the earlier example have been taught about reliability. They go back to visit the recruits again and obtain more information. This time they specifically plan to obtain consistent information. When they report back, one of the coaches states that his recruit drives a blue car. The second coach says that his recruit drives a green car. The problem of reliability has been resolved. The coaches are now providing the same information about the two recruits. However, this information most likely has nothing to do with performance on the football field. We thus conclude that the information does not have validity, which means that it is not relevant for job performance.

Validity

The quality of being justifiable. To be valid, a method of selecting employees must accurately predict who will perform the job well.

How do we know if a test is valid? Evidence of validity can come in many forms, and assessments of validity should take into account all evidence supporting a relationship between the assessment technique and job performance.18 Nevertheless, as with reliability, certain methods for determining validity are most commonly used.

One method, called the content validation strategy, involves determining whether the content of the assessment method is representative of the job situation. For instance, a group of computer programmers might be asked to look at a computer programming test to determine whether the test measures knowledge needed to program successfully. The experts match tasks from the job description with skills and abilities measured by the test. Analyses are done to learn if the experts agree. The content validation strategy thus relies on expert judgments, and validity is supported when experts agree that the content of the assessment reflects the knowledge needed to perform well on the job. Content validation is a particularly important step for developing new tests and assessments. As a student, you see content validation each time you take an exam. The course instructor acts as an expert who determines whether the questions on the exam are representative of the course material.

Content validation strategy

A process of estimating validity that uses expert raters to determine if a test assesses skills needed to perform a certain job.

A second method for determining validity is known as the criterion-related validation strategy. This method differs from the content validation strategy in that it uses correlation coefficients to show that test or interview scores are related to measures of job performance. For example, a correlation coefficient could be calculated to measure the relationship between a personality trait and the dollars of business that sales representatives generate. A positive correlation coefficient can indicate that those who have high scores on a test of assertiveness generate more sales. In this case, a negative correlation coefficient might also be instructive, as it would indicate that people who have lower scores on a particular trait, such as anxiety, have higher sales figures. Either way, the test scores will be helpful for making hiring decisions and predicting who will do well in the sales position.

Criterion-related validation strategy

A process of estimating validity that uses a correlation coefficient to determine whether scores on tests predict job performance.

In practice, two methods can be used to calculate criterion-related validity coefficients. One method uses the predictive validation strategy. Here, an organization obtains assessment scores from people when they apply for jobs and then later measures their job performance. A correlation coefficient is calculated to determine the relationship between the assessment scores and performance. This method is normally considered the optimal one for estimating validity. However, its use in actual organizations presents certain problems. One problem is that it requires measures from a large number of people. If an organization hires only one or two people a month, it might take several years to obtain enough information to calculate a proper correlation coefficient. Another problem is that organizations may also be reluctant to pay for ongoing measurement before they have evidence that the assessments are really useful for predicting performance.

Predictive validation strategy

A form of criterion-related validity estimation in which selection assessments are obtained from applicants before they are hired.

A second method for calculating validity coefficients uses the concurrent validation strategy. Here, the organization obtains assessment scores from people who are already doing the job and then calculates a correlation coefficient relating those scores to performance measures that already exist. In this case, for example, a personality test could be given to the sales representatives already working for the organization. A correlation coefficient could be calculated to determine whether sales representatives who score high on the test also have high sales figures. This method is somewhat easier to use, but it too has drawbacks. One problem is that the existing sales representatives do not complete the personality assessment under the same conditions as job applicants. Applicants may be more motivated to obtain high scores and may also inflate their responses to make themselves look better. Existing sales representatives may have also learned things and changed in ways that make them different from applicants, which might reduce the accuracy of the test for predicting who will perform best when first hired.

Concurrent validation strategy

A form of criterion-related validity estimation in which selection assessments are obtained from people who are already employees.

Neither the predictive nor the concurrent strategy is optimal in all conditions. However, both yield important information, and this information comes in the form of a correlation coefficient. How high should this correlation coefficient be? Validity coefficients are lower than reliability coefficients. This is because a reliability coefficient represents the relationship between two things that should be nearly identical. In contrast, a validity coefficient represents a relationship between two different things: the test or interview and job performance. Correlation coefficients representing validity rarely exceed .50. Many commonly used assessment techniques are associated with correlation coefficients that range from .25 to .50, and a few that are useful range from .15 to .25. This suggests that, as a guideline for assessing validity, a coefficient above .50 indicates a very strong relationship, coefficients between .25 and .50 indicate somewhat strong relationships, and correlations between .15 and .25 weaker but often important relationships.19 Once again, this information can help managers and human resource specialists become better consumers of assessment techniques. As with reliability, information about validity should be available for properly developed selection methods.

One additional concept related to validity is generalizability, which concerns the extent to which the validity of an assessment method in one context can be used as evidence of validity in another context. In some cases, differences in the job requirements across organizations might result in an assessment that is valid in one context but not in another. For instance, a test that measures sociability may predict high performance for food servers in a sports bar but not for servers in an exclusive restaurant. This variability is known as situational specificity. In other cases, differences across contexts do not matter, and evidence supporting validity in one context can be used as evidence of validity in another context, a condition known as validity generalization. A common example of a personality trait that exhibits generalization is conscientiousness. Being organized and goal oriented seems to lead to high performance regardless of the work context. We return to this subject later in discussions about different forms of assessment.

Situational specificity

The condition in which evidence of validity in one setting does not support validity in other settings.

Validity generalization

The condition in which evidence of validity in one setting can be seen as evidence of validity in other settings.

UTILITY

The third principle associated with employee selection methods is utility, which concerns the method's cost effectiveness. Think back to the football example. Suppose the university has decided to give all possible recruits a one-year scholarship, see how they do during the year, and then make a selection decision about which players to keep on the team. (For the moment, we will ignore NCAA regulations.) Given an entire year to assess the recruits, the university would likely be able to make very good selection decisions, but the cost of the scholarships and the time spent making assessments would be extremely high. Would decisions be improved enough to warrant the extra cost?

Utility

A characteristic of selection methods that reflects their cost effectiveness.

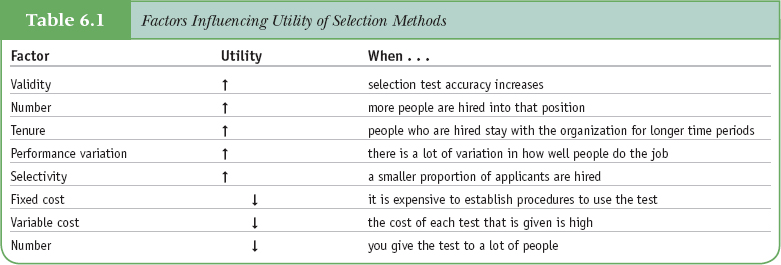

Several factors influence the cost effectiveness, or utility, of a selection method. The first issue concerns validity. All other things being equal, selection methods with higher validity also have higher utility. This is because valid selection methods result in more accurate predictions. In turn, more accurate predictions result in higher work performance, which leads to greater organizational profitability.

A second issue concerns the number of people selected into a position. An organization can generate more money when it improves its hiring procedures for jobs it fills frequently. After all, a good selection procedure increases the chances of making a better decision each time it is used. Even though each decision may only be slightly better than a decision made randomly or with a different procedure, the value of all the decisions combined becomes substantial. This explains why even selection decisions with moderate to low validity may have high utility.

A third issue concerns the length of time that people stay employed. Utility is higher when people remain in their jobs for long periods of time. This principle is clear when we compare the probable monetary return of making a good selection decision for someone in a summer job versus someone in a 40-year career. Hiring a great employee for a few months can be very helpful. Hiring a great employee for an entire career, however, can yield a much greater financial benefit.

A fourth issue that influences utility is performance variability. To understand this concept, think about the difference in performance of good and bad cooks at a fast-food restaurant versus the difference in performance of cooks at an elite restaurant. The fast-food cooking process is so standardized that it usually does not matter who cooks the food. In this case, making a great selection decision has only limited value. In contrast, the cooking process at an elite restaurant requires the cook to make many decisions that directly influence the quality of the food. Selecting a good cook in this situation is often the difference between a restaurant's success and failure. Measuring performance variability for specific jobs can be somewhat difficult. Just what is the dollar value associated with hiring a good candidate versus a bad one? A number of studies suggest that salary provides a good approximation of this value.20 Variability in performance increases as salary increases. The dollar value of hiring a good company president is greater than the dollar value of hiring a good receptionist, and this difference is reflected in the higher compensation provided to the company president.

A fifth issue involves the ratio of applicants to hires for a particular position and concerns how choosy an organization can be. An organization that must hire three out of every four applicants is much less choosy than an organization that hires one out of every ten. If an organization hires almost everyone who applies, then it will be required to hire people even when the selection method suggests that they will not be high performers. Because people are hired regardless of the assessment results, very little value comes from developing quality selection procedures. In contrast, an organization that receives a large number of applications for each position can benefit from good selection techniques that help accurately predict which of the applicants will be the highest performer.

Still another issue related to utility is cost. Cost issues associated with selection methods can be broken into two components: fixed costs associated with developing an assessment method and variable costs that occur each time the method is used. For example, an organization may decide to use a cognitive ability test to select computer programmers. The organization will incur some expenses in identifying an appropriate test and training assessors to use it. This cost is incurred when the test is first adopted. Most likely, the organization will also pay a fee to the test developer each time it gives the test to a job applicant. In sum, utility increases when both fixed and variable costs are low. In general, less-expensive tests create more utility, as long as their validity is similar to that of more-expensive tests.

Let's look more closely at the variable costs of the assessment. Because it costs money for each person to take an assessment, utility decreases as the number of people tested or interviewed increases. However, there is a tradeoff between the number of people being assessed and selectivity. Unless a test has low validity and is very expensive, the tradeoff usually works out such that the costs associated with giving the test to a large number of people are outweighed by the advantages of being choosy and hiring only the very best applicants.

Table 6.1 summarizes factors that influence utility. Of course, dollar estimates associated with utility are based on a number of assumptions and represent predictions rather than sure bets. Just like predictions associated with financial investments, marketing predictions, and weather forecasting, these estimates will often be wrong. Some research even suggests that providing managers with detailed, complex cost information does not help persuade them to adopt the best selection methods.21 This does not, however, mean that cost analyses are worthless. Utility estimates can be used to compare human resource investments with other investments such as buying machines or expanding market reach. Estimates are also more likely to be accepted by managers when they are presented in a less complex manner and when they are framed as opportunity costs.22 Managers can use utility concepts to guide their decisions. For instance, managers should look for selection procedures that have high validity and relatively low cost. They should focus their attention on improving selection decisions for jobs involving a large number of people who stay for long periods of time. They should also focus on jobs in which performance of good and bad employees varies a great deal and in which there are many applicants for each open position.

LEGALITY AND FAIRNESS

The fourth principle associated with selection decisions concerns legality and fairness. Think back to the football example again. Suppose the coaches decided to select only recruits who could pass a lie detector test. Is this legal? Chapter 3 specifically described a number of legal issues associated with human resource management.

Validity plays an important role in the legality of a selection method. As we discussed in Chapter 3, if a method results in lower hiring rates for members of a protected subgroup of people—such as people of a certain race—then adverse impact occurs. In this case, the company carries the burden of proof for demonstrating that its selection methods actually link with higher job performance. Because adverse impact exists in many organizations, being able to demonstrate validity is a legal necessity.

High validity may make it legal for an organization to use a test that screens out some subgroups at a higher rate than others, but this does not necessarily mean that everyone agrees that the test is fair and should be used. Fairness goes beyond legality and includes an assessment of potential bias or discrimination associated with a given selection method. Fairness concerns the probability that people will be able to perform satisfactorily in the job, even though the test predicted that they would not.

Fairness

A characteristic of selection methods that reflects individuals' perceptions concerning potential bias and discrimination in the selection methods.

From the applicants' perspective, selection procedures are seen as more fair if they believe they are given an opportunity to demonstrate their skills and qualifications.23 Because of this and other factors, assessments of fairness often depend a great deal on personal values. The very purpose of employee selection is to make decisions that discriminate against some people. Under optimal conditions, this discrimination is related only to differences in job performance. Yet no selection procedure has perfect validity. All techniques screen out some people who would actually perform well if given the opportunity. For example, some research has found that tests can unfairly screen out individuals who believe that people like them don't perform well on the specific test.24 For instance, a woman may not perform well on a mathematics test if she believes that women aren't good at math. Simply seeing the test as biased can result in decreased motivation to try hard and thereby lower scores, even though these people have the skills necessary to do the job.

Even tests with relatively high validity screen out a number of people who could perform the job. Thus, some employee selection procedures may provide economic value to organizations at the expense of individuals who are screened out even though they would perform well. This situation creates a tradeoff between a firm's desire to be profitable and society's desire for everyone with an equal chance to obtain quality employment. Perceptions of the proper balance between these values differ depending on personal values, making fairness a social rather than scientific concept.

ACCEPTABILITY

A final principle for determining the merit of selection techniques is acceptability, which concerns how applicants perceive the technique. Can a selection method make people see the organization as a less-desirable place to work? Think back to the football coaches. Suppose they came up with a test of mental toughness that subjected recruits to intense physical pain. Would completing the test make some recruits see the school less favorably? Would some potential players choose to go to other schools that did not require such a test?

Acceptability

A characteristic of selection methods that reflects applicants' beliefs about the appropriateness of the selection methods.

The football example shows that selection is a two-way process. As an organization is busy assessing people, those same people are making judgments about whether they really want to work for the organization. Applicants see selection methods as indicators of an organization's culture, which can influence not only their decisions to join the organization but also subsequent feelings of job satisfaction and commitment.25 Organizations should thus be careful about the messages that their selection techniques are sending to applicants.

In general, applicants have negative reactions to assessment techniques when they believe that the organization does not need the information being gathered—that the information is not job related. For instance, applicants tend to believe that family and childhood experiences are private and unrelated to work performance. Applicants also tend to be skeptical when they do not think the information from a selection assessment can be evaluated correctly. In this sense, many applicants react negatively to handwriting analysis and psychological assessment because they do not believe these techniques yield information that can be accurately scored.26

One interesting finding is that perceptions of fairness differ among countries. For instance, people in France see handwriting analysis and personality testing as more acceptable than do people in the United States. At the same time, people in the United States see interviews, résumés, and biographical data as more acceptable than do people in France.27

There is also some evidence that applicants react more positively to a particular assessment when they believe they will do well on it. One study, for example, found people who use illegal drugs to be less favorable about drug testing.28 Although this is hardly surprising, it does illustrate the complexity of understanding individual reactions to employee selection techniques.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

What Selection Methods Are Commonly Used?

Methods for selecting employees include testing, gathering information, and interviewing. We discuss particular practices associated with each of these categories in the sections that follow.

TESTING

Employment testing provides a method for assessing individual characteristics that help some people be more effective employees than others. Tests provide a common set of questions or tasks to be completed by each job applicant. Different types of tests measure knowledge, skill, and ability, as well as other characteristics, such as personality traits.

Cognitive Ability Testing

Being smart is often measured through cognitive ability testing, which assesses learning, understanding, and ability to solve problems.29 Cognitive ability tests are sometimes referred to as “intelligence” or “mental ability” tests. Some measure ability in a number of specific areas, such as verbal reasoning and quantitative problem solving. However, research suggests that general mental ability, which is represented by a summation of the specific measures, is the best predictor of performance in work contexts.30 Of course, cognitive ability is somewhat related to education, but actual test scores have been shown to predict job performance better than measures of educational attainment.31

Cognitive ability testing

Assessment of a person's capability to learn and solve problems.

In general, cognitive ability tests are very effective selection tools. Specifically, they have high reliability; people tend to score similarly at different times and on different test forms.32 In addition, these tests are difficult to fake, and people are generally unable to substantially improve their scores by simply taking courses that teach approaches to taking the test.33 Validity is higher for cognitive ability tests than for any other selection method.34 This high validity, combined with relatively low cost, results in substantial utility. Cognitive ability tests are good, inexpensive predictors of job performance.

A particularly impressive feature of cognitive ability tests is their validity generalization. They predict performance across jobs and across cultures.35 Everything else being equal, people with higher cognitive ability perform better regardless of the type of work they do.36 Nevertheless, the benefits of high cognitive ability are greater for more complex jobs, such as computer programmer or physician.37 One explanation is the link between cognitive ability and problem solving. People with higher cognitive ability obtain more knowledge.38 Example items from a widely used cognitive ability test are shown in Table 6.2. Can you see why these tests predict performance better in complex jobs? Researchers have also posited that people with higher cognitive ability adapt to change more quickly, although the actual evidence supporting better adaptation is inconsistent.39

Source: Sample items for Wonderlic Personnel Test-Revised (WPT-R). Reprinted with permission from Wonderlic, Inc.

A concern about cognitive ability tests is that people from different racial groups tend to score differently.40 This does not mean that every individual from a lower-scoring group will score low. Some individuals from each group will score better and some will score worse, but on average, some groups do worse than others. The result is adverse impact, wherein cognitive ability tests screen out a higher percentage of applicants from some minority groups. Because of their strong link with job performance, cognitive tests can be used legally in most settings. However, a frequent social consequence of using cognitive ability tests is the hiring of fewer minority workers.

In terms of acceptability, managers see cognitive ability as one of the most important predictors of work performance.41 Human resource professionals and researchers strongly believe in the validity of cognitive ability tests, even though some express concern about the societal consequences of their use.42 In contrast, job applicants often perceive other selection methods as being more effective.43 Not surprisingly, negative beliefs about cognitive ability tests are stronger for people who do not perform well on the tests.44

In summary, cognitive ability tests are a useful tool for determining whom to hire. As discussed in the “How Do We Know?” feature, these tests can predict long-term success. They predict potential more than achievement, making them best suited for organizations pursuing long-term staffing strategies. High cognitive ability is particularly important for success in organizations with long-term staffing strategies, as employees must learn and adapt during long careers. Using cognitive ability tests is thus beneficial for organizations seeking long-term generalists and specialists. Organizations seeking short-term generalists can also benefit by using these tests to inexpensively assess basic math and language ability.

Personality Testing

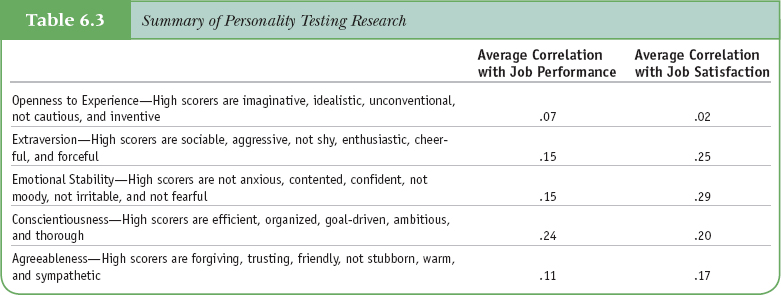

Personality testing measures patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior.45 Researchers have identified five broad dimensions of personality: agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, extraversion, and openness to experience.46 The five broad personality dimensions can be accurately measured in numerous languages and cultures, making the tests useful for global firms. Patterns of relationships with work performance are similar across national boundaries.47 A description of each dimension and a summary of its general relationships to job performance and job satisfaction are presented in Table 6.3.

Personality testing

Assessment of traits that show consistency in behavior.

Sources: Information from Timothy A. Judge, Daniel Heller, and Michael K. Mount, “Five-Factor Model of Personality and Job Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Applied Psychology 87 (2002): 530–541; Murray R. Barrick, Michael K. Mount, and Timothy A. Judge, “Personality and Performance at the Beginning of the Millennium,” International Journal of Selection and Assessment 9 (2001): 9–30.

Looking at personality tests in general, we find that measures for the five personality dimensions demonstrate adequate reliability.48 Different forms and parts of the test correlate highly with each other.

Personality tests with items that specifically ask about typical actions in employment settings tend to yield consistent measures of behaviors that are important at work.49 Specifically, relationships between personality dimensions and performance, which represent validity, are highest when tests specifically instruct people to respond in relation their work behavior, rather than in relation to their actions across different settings.50 Personality traits are generally good predictors of citizenship behavior such as helping others and going beyond minimum expectations.51 Yet, strength of validity often differs depending on the personality dimension being measured. In general, personality dimensions associated with motivation are good predictors of performance. One such dimension is conscientiousness.

Conscientious employees are motivated—they set goals and work hard to accomplish tasks.52 Conscientious people also tend to be absent from work less frequently.53 Conscientious workers are more satisfied with their jobs and are more likely to go beyond minimum expectations to make the organization successful.54 Conscientiousness thus exhibits validity generalization in that it predicts work performance regardless of the type of work. Research evidence suggests that emotional stability does not relate as strongly to performance as conscientiousness, yet, it too captures aspects of motivation and demonstrates validity generalization. People high on emotional stability are more confident in their capabilities, which in turn increases persistence and effort.55 Yet, people who are highly anxious can actually perform better in some contexts, such as air traffic controller, that require workers to pay very close attention to detail in a busy environment.56

Relationships with the other three personality dimensions depend on the work situation, meaning that these measures have situational specificity. Extraversion corresponds with a desire to get ahead and receive rewards, making it a useful predictor for performance in sales and leadership positions.57 More extraverted employees who are also more emotionally stable—think happy and bubbly personalities—have also been found to excel in customer-service jobs such as those found in a health and fitness center. Agreeableness is important for interpersonal relationships and corresponds with high performance in teams and service jobs that require frequent interaction with customers.58 Much of this effect occurs because agreeable employees are more likely to go beyond minimum expectations and help their coworkers.59 Openness to experience is seldom related to work performance, but recent research suggests that it can increase performance in jobs that require creativity and adaptation to change.60 One setting requiring adaptation is working in a foreign country, and people more open to experience do indeed perform better in such assignments.61 People who are more open to experience are also more likely to be entrepreneurs.62

A notable feature of personality tests is their helpfulness in predicting the performance of entire teams. Teams that include just one person who is low on agreeableness or conscientiousness have lower performance.63 This means that personality tests predict not only individual performance but also how an individual's characteristics will influence the performance of other people. This feature increases the utility of personality testing, because hiring someone with desirable traits yields benefits related not just to the performance of that individual but also to the performance of others.

As shown in Table 6.4, a survey of selection practices around the world suggests that personality testing is used more frequently in countries other than the U.S. Within the U.S a few states have laws that prohibit personality testing. However, in most cases, the use of personality tests does not present problems as long as organizations use well-developed tests that do not ask outwardly discriminatory questions.64 Personality tests do have some adverse impact for women and minorities. For minorities the negative effect is less than that for cognitive ability tests.65

Source: Information from Ann Marie Ryan, Lynn McFarland, Helen Baron, and Ron Page, “An International Look at Selection Practices: Nation and Culture as Explanations for Variability in Practice,” Personnel Psychology 52 (1999): 359–391.

With regard to acceptability, a common concern about the use of personality tests is the potential for people to fake their responses. Indeed, research has shown that people are capable of faking and obtaining higher scores when instructed to do so. Moreover, people do inflate their scores when they are being evaluated for selection.66 Although faking does have the potential to make personality tests less valid predictors of job performance,67 the overall relationship between personality measures and job performance remains,68 meaning that even with faking, personality tests can be valid selection measures. Using statistical procedures to try correcting for faking does little to improve the validity of tests.69 However, faking does involve issues of fairness. Some people fake more than others, and people who do not inflate their scores may be unfairly eliminated from jobs.70 Faking can thus lead to decisions that are unfair for some individuals, even though it has little negative consequence for the organization. To reduce the potentially negative impact on individuals, organizations can use personality tests in early stages of the selection process to screen out low scorers rather than in later stages to make final decisions about a few individuals.71 Obtaining personality scores from ratings provided by friends and coworkers rather than applicants themselves is also helpful, and current research is exploring the usefulness of techniques such as eye-tracking technology to identify when applicants are faking.72

Another method for reducing faking is to create personality tests with items that have less obvious answers. An example of this approach is a conditional reasoning test. Conditional reasoning tests are designed to assess unconscious biases and motives. With this approach, job applicants are asked to solve reasoning problems which do not have answers that are obviously right or wrong. People with certain tendencies base their decisions on particular forms of reasoning.73 For example, a person prone to aggression is more likely to attribute actions of others as hostile. What appears to be the most reasonable answer to the aggressive person (that other people do things because they are mean) is different from what less-aggressive people see as the most reasonable answer. Because they tap into unconscious beliefs, these tests are more difficult to fake.74 Unfortunately, conditional reasoning tests are somewhat difficult to create and as of yet do not measure the full array of personality traits.

Personality testing, then, is another generally effective tool for determining whom to hire. These tests are increasingly available on the Internet, as explained in the accompanying “Technology in HR” feature. This makes personality tests relatively simple to administer. Yet, personality tests often relate more to organization fit than to job fit, suggesting that personality measures are most appropriate in organizations that adopt long-term staffing strategies. People with personality traits that fit an organization's culture and work demands are more likely to remain with the organization.75 Personality testing is thus especially beneficial for organizations adopting Committed Expert and Loyal Soldier HR Strategies.

Situational Judgment Tests

Situational judgment tests are a relatively new development. These tests place job applicants in a hypothetical situation and then ask them to choose the most appropriate response. Items can be written to assess job knowledge, general cognitive ability, or practical savvy. Indeed, a potential strength of these tests is their ability to assess interpersonal skills, which are difficult to measure.76 Situational judgment tests also tend to capture broad personality traits such as conscientiousness and agreeableness, as well as tendencies toward certain behavior (like taking initiative) in more specific situations.77

Situational judgment test

Assessment that asks job applicants what they would do, or should do, in a hypothetical situation.

Some situational judgment tests use a knowledge format that asks respondents to pick the answer that is most correct. Other tests use a behavioral tendency format that asks respondents to report what they would actually do in the situation. Although the questions are framed a bit differently, the end result seems to be the same.78 Situational judgment tests have been found to have good reliability and validity. They predict job performance in most jobs, and they provide information that goes beyond cognitive ability and personality tests.79 Situational judgment tests thus appear to represent an extension of other tests. They closely parallel structured interviews, which we will discuss shortly. Questions can be framed to measure either potential in organizations with long-term orientations or achievement and knowledge in organizations with short-term labor strategies. They can also be designed to emphasize either general traits or specific skills. This makes them useful for organizations pursuing any of the human resource strategies.

Physical Ability Testing

Physical ability testing assesses muscular strength, cardiovascular endurance, and coordination.80 These tests are useful for predicting performance in many manual labor positions and in jobs that require physical strength. Physical ability tests can be particularly important in relation to the Americans with Disabilities Act, as organizations can be held liable for discrimination against disabled applicants. Managers making selection decisions should thus test individuals with physical disabilities and not automatically assume that they cannot do the job.

Physical ability tests have high reliability; people score similarly when the same test is given at different times. Validity and utility are also high for positions that require physical inputs, such as police officer, firefighter, utility repair operator, and construction worker.81 Validity generalization is supported for positions where job analysis has shown work requirements to be physically demanding.82

As long as job analysis has identified the need for physical inputs, physical ability testing presents few legal problems. However, men and women do score very differently on physical ability tests. Women score higher on tests of coordination and dexterity, whereas men score higher on tests of muscular strength.83 Physical ability tests thus demonstrate adverse impact. In particular, selection decisions based on physical ability tests often result in exclusion of women from jobs that require heavy lifting and carrying.

The usefulness of physical ability testing is not limited to a particular HR strategy. Physical tests can be useful for organizations seeking any form of talent, as long as the talent relates to physical dimensions of work.

Integrity Testing

In the past, some employers used polygraph—or lie detector—tests to screen out job applicants who might steal from them. However, the Employee Polygraph Protection Act of 1988 generally made it illegal to use polygraph tests for hiring decisions. Since then, organizations have increasingly turned to paper-and-pencil tests for integrity testing. Such tests are designed to assess the likelihood that applicants will be dishonest or engage in illegal activity.

Integrity testing

Assessment of the likelihood that an individual will be dishonest.

There are two types of integrity test: overt and covert. Overt tests ask questions about attitudes toward theft and other illegal activities. Covert tests are more personality-based and seek to predict dishonesty by assessing attitudes and tendencies toward antisocial behaviors such as violence and substance abuse.84

Research evidence generally supports the reliability and validity of integrity tests. These tests predict absenteeism and overall performance, but they most strongly correspond with counterproductive work behavior such as theft, property destruction, unsafe actions, poor attendance, and intentional poor performance.85 Most often, such tests are used in contexts that involve the handling of money, such as banking and retail sales.

In many ways, integrity tests are similar to personality tests. In fact, strong correlations exist between integrity test scores and personality test scores, particularly for conscientiousness.86 As with personality tests, a concern is that people may fake their responses when jobs are on the line. The evidence suggests that people can and do respond differently when they know they are being evaluated for a job. Even so, links remain between test scores and subsequent measures of ethical behavior.87 Furthermore, integrity tests show no adverse impact for minorities88 and appear to predict performance consistently across national cultures.89

Integrity tests can be useful for organizations with Bargain Labor HR strategies. These firms hire many entry-level workers to fill positions in which they handle substantial amounts of money. In such cases, integrity tests can provide a relatively inexpensive method for screening applicants. This explains why organizations like grocery stores, fast-food chains, and convenience stores make extensive use of integrity testing to select cashiers.90

Drug Testing

Drug testing normally requires applicants to provide a urine sample that is tested for illegal substances. It is quite common in the United States, perhaps because, according to some estimates as much as 14 percent of the workforce uses illegal drugs, with as many as 3 percent of workers actually using drugs while at work.91 Illegal drug use has been linked to absenteeism, accidents, and likelihood of quitting.92 Drug testing, which is both reliable and valid, appears to be a useful selection method for decreasing such nonproductive activities. Even though administration costs can be high, basic tests are modestly priced, supporting at least moderate utility for drug testing.

Research related to drug testing has looked at how people react to being tested. In general, people see drug testing as most appropriate for safety-sensitive jobs such as pilot, heart surgeon, and truck driver.93 Not surprisingly, people who use illicit drugs are more likely to think negatively about drug testing.94

Drug testing can be useful for firms that hire most types of talent. Organizations seeking short-term generalists use drug testing in much the same way as integrity testing. Organizations with long-term employees frequently do work that requires safe operational procedures. In these organizations, drug testing is useful in selecting people for positions such as forklift operator, truck driver, and medical care provider.

Work Sample Testing

One way of assessing specific skills is work sample testing, which directly measures performance on some element of the job. Common examples include typing tests, computer programming tests, driving simulator tests, and electronics repair tests. In most cases, these tests have excellent reliability and validity.95 Many work sample tests are relatively inexpensive as well, which translates into high utility. Because they measure actual on-the-job activities, work sample tests also involve few legal problems. However, in some cases work test scores are lower for members of minority groups.96

Work sample testing

Assessment of performance on tasks that represent specific job actions.

A problem with work sample tests is that not all jobs lend themselves to this sort of testing. What type of work sample test would you use for a medical doctor or an attorney, for example? The complexity of these jobs makes the creation of work sample tests very difficult. However, human resource specialists have spent a great deal of time and effort developing a work sample test for the complex job of manager. The common label for this tool is assessment center.

Assessment center

A complex selection method that includes multiple measures obtained from multiple applicants across multiple days.

Assessment center participants spend a number of days with other managerial candidates. Several raters observe and evaluate the participants' behavior across a variety of exercises. In one typical assessment center exercise, the leaderless group discussion, for example, managerial candidates work together in a group to solve a problem in the absence of a formal leader. For the in-basket exercise, participants write a number of letters and memos that simulate managerial decision making and communication. Managers and recruiters from the organization serve as observers who rate the participants in areas such as consideration and awareness of others, communication, motivation, ability to influence others, organization and planning, and problem solving.97

Assessment centers have good reliability and validity, which suggests that they can be excellent selection tools in many contexts.98 Validity improves when assessment center evaluators are trained and when exercises are specifically tailored to fit the job activities of the participants.99 Minority racial groups have been found to score lower in assessment centers, but women often score higher.100 Creating and operating an assessment center can be very expensive, which substantially decreases utility for many organizations. Because of their high cost, assessment centers are normally found only in very large organizations.

Assessment centers are most common in organizations with long-term staffing strategies, particularly those adopting Committed Expert HR strategies. Proper placement of individuals is extremely critical for these organizations, and the value of selecting someone for a long career offsets the high initial cost of assessment. Other types of work sample tests are useful for organizations pursuing any of the staffing strategies. A typing test can be a valuable aid for hiring a temporary employee as part of a Bargain Laborer HR strategy, for example. Similarly, a computer programming test can be helpful when hiring someone as part of a Free Agent HR strategy.

INFORMATION GATHERING

In addition to tests, organizations use a variety of methods to directly gather information about the work experiences and qualifications of potential employees. In fact, as illustrated in the “Building Strength Through HR” feature, most organizations combine multiple methods of testing and information gathering. Common methods for gathering information include application forms and résumés, biographical data, and reference checking.

Application Forms and Résumés

Many entry-level jobs require potential employees to complete an application form. Application forms ask for information such as address and phone number, education, work experience, and special training. For professional-level jobs, similar information is generally presented in résumés. The reliability and validity of these selection methods depends a great deal on the information being collected and evaluated. Measures of things such as work experience and education have at least moderately strong relationships with job performance.101

With regard to education, the evidence shows that what you do in college really does matter. Employees with more education are absent less, show more creativity, and demonstrate higher task performance.102 People who complete higher levels of education and participate in extracurricular activities are more effective managers. Those who study humanities and social sciences tend to have better interpersonal and leadership skills than engineers and science majors.103 Grades received, particularly in a major, also have a moderate relationship with job performance, even though managers do not always use grades for making selection decisions.104

Application forms and résumés also provide valuable information about work experience. People with more work experience have usually held more different positions, been in those positions for longer periods, and more often done important tasks.105 Because they have been exposed to many different tasks, and because they have learned by doing, people with greater experience are more valuable contributors. In addition, success in previous jobs demonstrates high motivation, and executives with more experience are better at strategic thinking.106 Work experience thus correlates positively with performance, particularly when performance is determined by output measures such as production or amount of sales.107

One special advantage of application forms and résumés is their utility. Because these measures are generally inexpensive, they are frequently used as early screening devices. In terms of legality and fairness, measures of education and experience do have some adverse impact.108 Information being obtained from application forms and résumés should therefore be related to job performance to ensure validity.

Application forms and résumés can provide important information about past achievements, which makes them most valuable for organizations seeking people with specific skills. However, these selection tools can also capture potential and fit, so many organizations seeking long-term employees find them useful as well. Application forms are used mostly in organizations hiring generalists. They provide good measures of work experience and education that help identify people who have been dependable in jobs and school. Résumés are more commonly used in organizations that hire specialists. In particular, résumés provide information about experience and education relevant to a particular position.

Biographical Data

Organizations also collect biographical data, or biodata, about applicants. Collecting biodata involves asking questions about historical events that have shaped a person's behavior and identity.109 Some questions seek information about early life experiences that are assumed to affect personality and values. Other questions focus on an individual's prior achievements based on the idea that past behavior is the best predictor of future behavior. Common categories for biographical questions include family relationships, childhood interests, school performance, club memberships, and time spent in various leisure activities. Specific questions might include the following:

Biographical data

Assessment focusing on previous events and experiences in an applicant's life.

How much time did you spend with your father when you were a teenager?

What activities did you most enjoy when you were growing up?

How many jobs have you held in the past five years?

Job recruiters frequently see these measures as indicators of not only physical and mental ability but also interpersonal skill and leadership.110 The information provided by biodata measures does not duplicate information from other measures, such as personality measures, however.111

Biodata measures have been around for a long time, and they are generally useful for selecting employees. Scoring keys can be developed so that biodata responses can be scored objectively, just like a test. Objective scoring methods improve the reliability and validity of biodata. With such procedures, biodata has adequate reliability.112 Validity is also good, as studies show relatively strong relationships with job performance and employee turnover.113 In particular, biodata measures appear to have high validity for predicting sales performance.114 One common concern has been the validity generalizability of biodata. Questions that link with performance in one setting may not be useful in other settings. However, some recent research suggests that carefully constructed biographical measures can predict performance across work settings.115 Identifying measures that predict work performance across settings can help overcome a weakness of biodata, which is the high initial cost of creating measures. Finding items that separate high and low performers can take substantial time and effort, making items that predict performance across settings highly desirable.

Some human resource specialists express concern about legality and fairness issues with biodata. Much of the information collected involves things beyond the control of the person being evaluated for the job and is likely to have adverse impact for some. For instance, children from less wealthy homes may not have had as many opportunities to read books. Applicants' responses may also be difficult to verify, making it likely that they will fake. Using questions that are objective, verifiable, and job-related can minimize these concerns.116

Biodata measures can benefit organizations, whatever their staffing strategies. Organizations seeking long-term employees want to measure applicants' potential and should therefore use biodata measures that assess core traits and values. In contrast, organizations seeking short-term employees want to measure achievement and can benefit most from measures that assess verifiable achievements.

Reference Checking

Reference checking involves contacting an applicant's previous employers, teachers, or friends to learn more about the applicant. Reference checking is one of the most common selection methods, but available information suggests that it is not generally a valid selection method.117

The primary reason reference checking may not be valid relates to a legal issue. Organizations can be held accountable for what they say about current or past employees. A bad reference can become the basis for a lawsuit claiming defamation of character, which occurs when something untrue and harmful is said about someone. Many organizations thus adopt policies that prevent managers and human resource specialists from providing more than dates of employment and position. Such information is, of course, of little value. Even when organizations allow managers to give more information, the applicant has normally provided the names only of people who will give positive recommendations.

Defamation of character

Information that causes injury to another's reputation or character; can arise as a legal issue when an organization provides negative information about a current or former employee.