How Can Strategic Recruiting Make an Organization Effective?

Employee recruiting is the process of identifying and attracting people to work for an organization.1 The basic goals of recruiting are to communicate a positive image of the organization and to identify and gain the interest and commitment of people who will be good employees. Effective recruiting thus entails getting people to apply for positions, keeping applicants interested in joining the organization, and persuading the best applicants to accept job offers.2

Employee recruiting

The process of getting people to apply for work with a specific organization.

Organizations that recruit well have more options when it comes to hiring new employees. They are in a position to hire only the best. Good recruiting can also lower employment costs by making sure that new employees know what to expect from the organization, which helps keep employees on board once they are hired. Obtaining sufficient numbers of applicants and using the best recruitment sources have been linked to increased profitability.3 In short, a strategic approach to recruiting helps an organization become an employer of choice and thereby obtain and keep great employees who produce superior goods and services.

One example of effective recruiting is Google. The Internet search company has frequently been identified as a top place to work. It receives as many as 1,300 résumés a day.4 Having so many people apply for jobs puts Google in a position to hire only the best. Working at Google is so desirable that 95 percent of job applicants who receive an offer accept it.5 It takes effective recruiting to convince so many people to apply and to have such a high percentage of offers accepted. What makes Google the kind of place where so many people want to work? And what makes it the kind of place where very few quit?

The first key to successful recruiting at Google is a culture that creates a fun and supportive working environment. Given its competitive emphasis on differentiation and creativity, Google benefits from allowing employees the freedom to be themselves. Engineers are encouraged to dedicate 20 percent of their work time to new and interesting projects that are not part of their formal work assignments. The company also provides a number of benefits that allow employees to focus on completing work. For example, Google provides onsite support for personal tasks such as dry cleaning, haircuts, and oil changes. Yet, the perk that seems to create the most excitement is gourmet food. Employee cafeterias offer free food and cater to unique tastes with dishes like roast quail and black bass with parsley pesto.6 The supportive environment allows employees to focus their energy on getting work done rather than running personal errands, and the company is rewarded by employees willing to work long hours.

The culture at Google is particularly supportive of parents with family responsibilities. When the company was young and only had two employees with children, founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin suggested that a conference room be converted into an onsite daycare. The family-friendly focus continues today with new mothers getting three months of leave while receiving 75 percent of their salary. New fathers receive two weeks' paid leave. Free meals are also delivered to the homes of new parents.7 Lactation rooms and company-provided breast pumps help new mothers transition back to the workplace. Google has thus developed a reputation as an employer who helps balance work and family demands. Such efforts help make it so that only about 3 percent of staff members leave the company.8

So what does Google do to recruit employees? One effective recruitment source is referrals from current employees. Current employees are given a $2,000 bonus for each new employee they help recruit.9 Google also works closely with university professors to make sure they refer their best students for jobs. Another innovative recruiting source is contests. For example, Google once hosted an India Code Jam where computer experts competed to earn a prize for writing computer code. The contest drew 14,000 participants trying to win the prize of approximately $7,000. However, the real reason for the contest was to identify top talent, with about 50 finalists eventually being offered positions at Google.10

How Is Employee Recruiting Strategic?

As shown in the Google example, employee recruiting is strategic when it focuses on attracting people who will make great employees. Of course, recruiting practices that are successful at Google may not be as successful at other places. Google's business model requires hiring people with very specific skill sets. In such a situation, success in recruiting depends on receiving applications from the best and the brightest people available. Organizations that desire employees with less-specific skill sets may benefit from very different recruiting methods. Recruiting practices are thus best when they align with overall HR strategies.

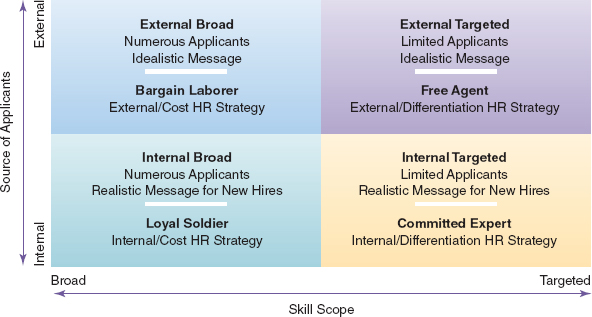

Figure 5.1 shows how selection decisions can be aligned with the HR strategies from Chapter 2. As the figure shows, two important dimensions underlie strategic recruiting choices: skill scope and source of applicants. We examine these dimensions next.

BROAD VERSUS TARGETED SKILL SCOPE

The horizontal dimension in Figure 5.1 represents differences in skill scope. At one end of the continuum is broad scope, which represents a set of work skills that a lot of people have. At the other end is targeted scope, which represents a set of skills that only a few people have.

Broad Scope

One way to think about differences in skill scope is to think about potential strategies for romantic dating. Suppose you wish to find a romantic partner. How do you go about finding him or her? One approach is to try to meet as many people as possible. You attend lots of different social events, talk with a variety of people, and go on numerous dates with different people. This strategy might work if you aren't that picky when it comes to relationship partners. Casting a wide net also makes sense if you are not sure about the type of person you're looking for. It also helps if you have a lot of time to evaluate potential partners. Such an approach to dating can be summarized as “How do I know what I want until I've seen what's out there?”

Figure 5.1 Strategic Framework for Employee Recruiting.

Some organizations adopt employee recruiting strategies that are very similar to dating a lot of different people. These organizations cast a wide net and try to get many people to apply for positions. This broad skill scope strategy focuses on attracting a large number of applicants. Such an approach makes sense when a lot of people have the characteristics needed to succeed in the job. McDonald's is a good example, since it is constantly working to attract numerous people who do not have highly specialized skills. Successful employees learn skills on the job, and the constant need for new employees requires maintaining a large pool of potential workers. Broad recruiting practices can also be helpful when an organization is recruiting for a new position where the characteristics of a successful worker are unclear or where a number of different characteristics might lead to success.

Broad skill scope

A recruiting strategy that seeks to attract a large number of applicants.

In terms of the HR strategies discussed in Chapter 2, broad scope recruiting is most often used by organizations with cost leadership strategies. Organizations using the Bargain Laborer HR strategy hire a large number of nonspecialized employees, who often stay with the company for only short periods of time. These organizations are therefore constantly searching for new employees. In many cases, they are not too choosy about whom they hire. Most people have the necessary skills. Of course, organizations using the Loyal Soldier HR strategy seek to keep employees for longer periods, but again, the employees do not need specialized skills to succeed. Most people have what it takes to perform the job tasks, and having a lot of applicants provides the organization with many alternatives. This means that successful recruiting for organizations with Loyal Soldier HR strategies often entails attracting a large number of applicants for each position and then basing hiring decisions on assessments of fit with the culture and values of the organization. Broad scope recruiting is thus optimal for organizations with both internal and external forms of the cost strategy.

Targeted Scope

Although dating a lot of different people is one approach to finding a romantic partner, it certainly isn't the only approach. You might instead establish a very clear set of characteristics desired in a mate and then date only people who are likely to have those characteristics. Instead of going to as many different parties as possible, you might just go to parties where you know certain types of people will be. You would not go on dates with people who clearly don't meet your expectations. Such an approach makes sense if you know exactly what you want and if you don't want to waste time meeting people who are clearly wrong for you. This approach to dating can be summarized as “I know exactly what I want, and all I need to do is find that person.”

A number of organizations adopt recruiting strategies that are similar to this targeted approach for dating. The targeted skill scope strategy seeks to attract a small group of applicants who have a high probability of possessing the characteristics needed to perform the specific job. Such an approach makes sense when only a select few have what it takes to perform the job successfully. Recruiting a university professor is one example of such a targeted approach. Only a small number of people have the education and experience necessary to work as professors. Receiving and reviewing applications from people without the required expertise wastes valuable time and resources. Universities thus benefit from targeting their recruiting to attract only qualified applicants.

Targeted skill scope

A recruiting strategy that seeks to attract a small number of applicants who have specific characteristics.

As you might expect, targeted scope recruiting is most often pursued by organizations with a competitive strategy of differentiation. Differentiation HR strategies rely on specific contributions from a select group of employees. People are hired because they have rare skills and abilities, and only a small number of people actually have what it takes to succeed. Receiving applications from a large number of people who clearly do not have the characteristics needed to perform the work is wasteful. Targeted scope recruiting is thus optimal for organizations with both Committed Expert and Free Agent HR strategies. These organizations benefit from identifying and attracting only the people who are most likely to be successful.

Skill Scope and Geography

One caution when thinking about targeted and broad approaches is to distinguish skill scope from geographic scope. Broad skill scope recruiting seeks to identify a large number of people. Given that many people have the required skills, this recruiting can usually be done in small geographic areas near where the new employees will work. Most likely, a sufficient number of recruits already living in the area can be identified. For instance, a local grocery store recruits cashiers by looking for people who already live close to the store. In contrast, targeted recruiting seeks to identify a smaller group of people with specialized skills and abilities. The number of qualified people in a particular area often is not large. Thus, targeted skill recruiting frequently covers wide geographic areas. An example is a law firm that conducts a nationwide search to identify a patent attorney. In summary, the terms broad and targeted refer to the range of applicant skills and not the geographic area of the recruiting search.

INTERNAL VERSUS EXTERNAL SOURCING

Think back to our dating example. What are the chances you are already friends with the person who will become your romantic partner? Should you try and develop deeper relationships with people you already like? Or do you want to identify new and exciting prospects? These questions start to touch on the next aspect of strategic recruiting—internal versus external sourcing. The vertical dimension in Figure 5.1 represents this aspect of recruiting, with internal sourcing at one end of the continuum and external sourcing on the other.

Internal Sourcing

Internal sourcing of recruits seeks to fill job openings with people who are already working for the organization. Positions are filled by current employees who are ready for promotions or for different tasks. These people have performance records and are already committed to a relationship with the organization. Because a lot is known about the motivation and skill of current employees, the risks associated with internal recruiting are relatively low. Of course, internal sourcing is a fundamental part of Loyal Soldier and Committed Expert HR strategies. With the exception of hiring entry-level workers, most organizations with these HR strategies try to fill as many job vacancies as possible by recruiting current employees.

Internal sourcing

A recruiting strategy that fills job openings by transferring people who are already working in the organization.

A common example of internal sourcing is organizations looking at current employees to identify people who can fill international assignments. The people filling these assignments, usually referred to as expatriates, move to a foreign country to take a work assignment that will last for a few years. Such assignments help organizations better take advantage of the skill and expertise of people who are already working for the company. Employees who serve as expatriates also develop new skills that can help them in their future assignments. Historically, expatriate workers have received high wages and benefits to offset the potential pains of relocation. However, foreign assignments are becoming more common, and many expatriates now receive pay similar to what they would receive in their home country.11

External Sourcing

External sourcing of recruits seeks to fill job openings with people from outside the organization. Primary sources of recruits are other organizations. The high number of entry-level positions in organizations with a Bargain Laborer HR strategy often necessitates external sourcing. Almost all employees are hired to fill basic jobs, and there are few opportunities for promotion or reassignment. Organizations with a Free Agent HR strategy also use primarily external sourcing. Bringing in a fresh perspective is key for these organizations. Since little training and development is provided, current employees rarely have the specialized skills needed to fill job openings. External sourcing, then, is an essential part of the recruiting practices of organizations with either Bargain Laborer or Free Agent HR strategies.

External sourcing

A recruiting strategy that fills job openings by hiring people who are not already employed by the organization.

An extreme example of external sourcing occurs when organizations do not actually hire people to fill positions. For example, positions may be filled by temporary workers, who are people actually employed by an outside staffing agency.12 Organizations often use such arrangements to avoid long-term employment commitments. This makes it easier to adjust the size of the workforce to meet increasing or decreasing demand for products and services. A potential disadvantage of using temporary workers is that it involves sharing employees with other organizations, which makes it difficult to develop a unique resource that creates a competitive advantage.13 In some cases, organizations hire successful temporary workers into permanent positions—a practice we revisit later in this chapter when we discuss employment agencies.

Temporary workers

Individuals who are employed by an outside staffing agency and assigned to work in an organization for a short period of time.

Another example of extreme external sourcing is independent contractors, who have a relationship with the organization but technically work for themselves.14 An example of a company that uses independent contractors is Newton Manufacturing, which sells promotional products such as coffee mugs and caps.15 Newton products are distributed by approximately 800 independent sales representatives. These representatives set their own hours and make their own decisions about how to sell. Representatives receive a percentage of their sales receipts, but they are not actually employed by Newton.

Independent contractors

Individuals who actually work for themselves but have an ongoing relationship with an organization.

Temporary workers and independent contractors are examples of contingent workers—people working without either an implicit or an explicit contract for continuing work and who are not required to work a minimum number of hours.16 Cost savings are often cited as a potential benefit of using contingent workers. A potential problem is that organizations have limited control over the actions of contingent workers. Many experts also believe that contingent workers have weaker commitment and motivation. However, research suggests that contingent workers generally feel high levels of support from their associated organizations.17 Much of this support seems to come from a feeling that the contingent worker status allows them to effectively balance their professional career with other life interests.18 Nevertheless, contingent workers need to proactively learn new skills and develop a progressive career. They can do this by continually demonstrating competence, building relationships to get referred to other projects, and framing their skill sets in terms of new opportunities.19

Contingent workers

People working without either an implicit or an explicit contract and who are not required to work a minimum number of hours.

REALISTIC VERSUS IDEALISTIC MESSAGING

Another important aspect of dating is how much you tell others about yourself. One approach is to be on your best behavior and only tell people the good things. This is similar to idealistic messaging, wherein an organization conveys positive information when recruiting employees in order to develop and maintain an upbeat image. An opposite approach to dating is to let others see the real you. This necessitates sharing not only positive information but also information about your problems and weaknesses. Such an approach is similar to realistic messaging, which occurs when an organization gives potential employees both positive and negative information about the work setting and job.

Idealistic messaging

The recruiting practice of communicating only positive information to potential employees.

Realistic messaging

The recruiting practice of communicating both good and bad features of jobs to potential employees.

Realistic Messaging

Realistic messaging is used to increase the likelihood that employees will stay with the organization once they have been hired. Job applicants are given realistic job previews designed to share a complete picture of what it is like to work for the organization. These previews usually include written descriptions and audiovisual presentations about both good and bad aspects of the working environment.20 Negative things such as poor working hours and frequent rejection by customers are specifically included in the recruiting message. That way, new recruits already know that the working environment is less than perfect when they start the job. Their expectations are lower, so they are less likely to become disappointed and dissatisfied. The overall goal of realistic messaging is thus to help new recruits develop accurate expectations about the organization. Lowered expectations are easier to meet, which decreases the chance of employees leaving the organization to accept other jobs.21 Studies such as the one described in the “How Do We Know?” feature also suggest that realistic job previews increase perceptions of honesty by the organization, which in turn make employees less likely to leave.

Realistic job previews

Information given to potential employees that provides a complete picture of the job and organization.

In terms of the HR strategies presented in Chapter 2, realistic messaging is most valuable for organizations seeking long-term employees. These organizations benefit from the reduced employee turnover that comes from realistic recruiting. The recruiting process provides an opportunity for people to get a sense of how well they will fit. If the organization does not provide honest and realistic information, then the assessment of the potential for a good longterm relationship is less accurate.

Realistic recruiting thus operates much like being truthful while dating. People make commitments with full knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of the other party, increasing the likelihood that their expectations will be met in the future. Being honest increases the likelihood of developing a successful long-term relationship. Since maintaining long-term relationships with employees is critical for the success of organizations pursuing either Loyal Soldier or Committed Expert HR strategies, realistic recruiting is most appropriate for these organizations.22 Of course, internal job applicants who are working for the organization already have a realistic picture of the work environment. The key for these organizations is thus to use realistic job previews for new hires. The importance of realistic messaging for new hires with internal labor strategies is shown in Figure 5.1, which suggests that even though most hires come internally, those who do come from outside sources should receive realistic job previews.

Idealistic Messaging

Unlike realistic messaging, idealistic messaging excludes negative information and paints a very positive picture of the organization. This positive emphasis can be helpful because realistic recruiting messages discourage some job applicants and cause them to look for work elsewhere.23 Unfortunately, in many cases, highly qualified applicants who have many other alternatives are the most likely to be turned off by realistic recruiting.24

Let's think about idealistic messaging in terms of our dating situation. Withholding negative information from a partner may work for a while, but when the “honeymoon” is over, faults are seen and satisfaction with the relationship decreases. Clearly, this is not an effective strategy for building a longterm relationship. But maybe a short-term relationship is all you want, so you aren't concerned that your partner will enter the relationship with unrealistic expectations. Once you get to know each other's faults and weaknesses, both of you may be ready to move on to other relationships. You might also be concerned that sharing negative information will scare some potential partners off before they get a chance to really know you.

In recruiting, too, idealistic messaging corresponds best with an emphasis on short-term relationships. This is shown in Figure 5.1 by the use of idealistic messaging for organizations pursuing external HR strategies. In particular, the Bargain Laborer HR strategy is used by organizations seeking to reduce cost through high standardization of work practices. Finding people to work in these lower-skilled jobs for even a short period of time, such as a summer, may be all that can be expected. Training for the job is minimal, so replacing people who quit is not as costly as replacing more-skilled workers. The Free Agent HR strategy requires people with more highly developed work skills, but these individuals are expected to be more committed to careers than to a particular organization. They likely have many choices of where to work, and negative information may push them to take a position elsewhere. In these cases, idealistic messaging may lead to inflated expectations about how good the job will be, but that may not matter a great deal because the new recruit is not expected to become a loyal long-term employee.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

How Does Human Resource Planning Facilitate Recruiting?

An important part of recruiting is planning. Organizations fail to take advantage of available talent when they begin recruiting only after a job is vacant. Carefully constructed recruiting plans not only increase the chances of identifying the best workers but also reduce costs associated with finding workers. In this section, we explore specific ways that an organization can plan and maximize recruiting effectiveness. First, we look at the overall planning process. We then describe differences between organizations that hire employees periodically in groups and organizations that have ongoing recruiting efforts. We also explore differences between a recruiting approach that is consistent across the entire organization and an approach that allows different departments and locations to develop their own recruiting plans.

THE PLANNING PROCESS

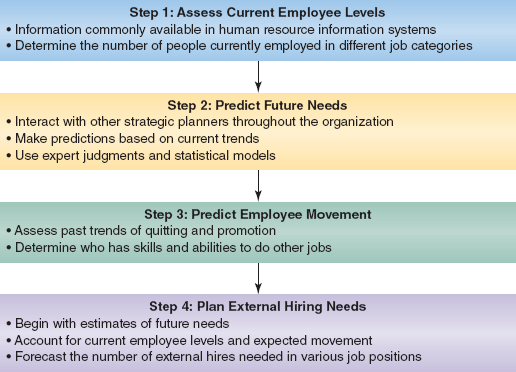

Human resource planning is the process of forecasting employment needs. A proactive approach to forecasting can help organizations become more productive. The basic steps of human resource planning are shown in Figure 5.2. The process involves assessing current employment levels, predicting future needs, planning for internal movement, and predicting external hiring needs. This planning process is similar to models of inventory control. First, you figure out what you currently have; next, you determine what you expect to need in the future; and then you plan where to obtain additional inventory.

Human resource planning

The process of forecasting the number and type of employees that will be needed in the future.

Figure 5.2 Human Resource Planning.

Step 1. Assessing Current Employment Levels

The first step of human resource planning, assessing current employment levels, relies heavily on the organization's information system. Most large corporations have some type of HR information system, with the most common systems being SAP and Oracle's PeopleSoft. These databases track employees and can generate reports showing where people are currently working. This information provides a snapshot summary of the number of people in different positions. The HR information system can also provide details about the qualifications and skills of current employees. This is helpful in planning for internal movement of people during the third planning step.

Step 2. Predicting Future Needs

The second step in human resource planning is to predict future needs. This step requires close collaboration with strategic planners throughout the organization. Predicting future needs begins with assessing environmental trends (changing consumer tastes, demographic shifts, and so forth). Based on these trends, a forecast is made of expected changes in demand for services and goods. Will people buy more or less of what the company produces? Such projections are used to predict the number of employees that might be needed in certain jobs.

One common method for making employment predictions is to assume that human resource needs will match expected trends for services and goods. For instance, an organization may assume that the number of employees in each position will increase by 10 percent during the upcoming year simply because sales are expected to grow by 10 percent in that period. More sophisticated forecasting methods might account for potential differences in productivity that come from developments in areas such as technology, interest rates, and unemployment trends. In some cases, projected changes are entered into statistical models to develop forecasts. In other cases, managers and other experts simply make guesses based on their knowledge of trends. Although specific practices vary, the overall goal of the second step is to combine information from the environment with the organization's competitive objectives in order to forecast the number of employees needed in particular jobs.25

Step 3. Predicting Employee Movement

The third step in planning is to predict movement among current employees. An example of benefits from planning is shown in the “Building Strength Through HR” feature. Generally, predictions assume that past patterns will repeat in the future. Historical data is assessed to determine how many employees in each job category can be expected to quit or be terminated during the next year. Measures such as quit rates, average length of time in specific jobs, and rates of promotion are used. As mentioned earlier, the organization's information system can be used to determine how many individuals have skills and experiences that qualify them for promotions or lateral moves. Although this information may not be exact, it does provide a rough idea of where current employees are likely to move. Information about employee skills can be particularly helpful for multinational organizations. Being able to identify the skills of employees currently residing in other countries helps build consistency across organizations. In all cases, using the information to make decisions and plan for the future gives the organization a competitive edge over firms that begin to fill positions only after someone leaves a job.

Figure 5.3 Illustration of Human Resource Planning.

Step 4. Planning External Hiring

The final step is to determine the number and types of people to be recruited externally. This is accomplished by combining the information from the first three steps. An example of a spreadsheet illustrating all steps is shown in Figure 5.3. Information from Step 2 is used to forecast the total number of employees needed in each position, and information from Steps 1 and 3 is used to determine how many of the projected positions can be filled by people already in the organization. The difference between the number needed and the number available provides an estimate of the number of new employees who will need to be recruited from outside the organization.

Of course, the information and strategies developed through the HR planning process are only estimates and are usually not totally accurate. Nevertheless, careful planning allows organizations to act strategically rather than simply react to changes. Good planning can eliminate many surprises. It can help to smooth out upward and downward trends in employee count to reduce or eliminate those instances in which an organization terminates good employees because of low need in certain areas only to realize a few months later that it has openings to fill in those same areas. It can also help organizations take advantage of opportunities to hire exceptional employees even before specific positions are open. Overall, HR planning takes a long-term perspective on hiring and develops ongoing tactics to make sure high-quality people are available to fill job vacancies.

BATCH AND FLOW APPROACHES

Human resource planning can help organizations develop consistent approaches to recruiting. Some organizations use a batch approach to recruiting, whereas others use a flow approach. A batch approach involves engaging in recruiting activities periodically. A flow approach involves sustained recruiting activities to meet the ongoing need for new employees.26

Batch approach

Recruiting activities that bring new employees into the organization in groups.

Flow approach

Recruiting activities that are ongoing and designed to constantly find new employees.

The flow approach views recruiting as a never-ending activity. The planning process is used to forecast employment needs. New employees are frequently added even before specific positions are open. An organization using a flow approach continually seeks top recruits and brings them onboard when they are available. This enables the organization to take advantage of opportunities as they arise and helps it to avoid being forced to hire less-desirable applicants because nobody better is available at the time.

Batch recruiting is different in that it operates in cycles. Groups of employees are recruited together. Organizations may adopt a batch approach when new employees are only available at certain times. For instance, organizations that recruit college students usually must adopt a batch approach because students are available only at the end of a semester. Organizations also adopt a batch approach when they need to train new employees in a group or when a specific work project has a clear beginning and end. For example, a biological research organization may hire people to work on specific grants. Employees are hired in a group when a new grant begins.

A flow approach to recruiting is optimal in most cases because it allows organizations to operate strategically. Employment needs can be planned in advance, and ongoing activities can reduce the time between job openings and hiring decisions. Organizations that use a batch approach to recruiting can also benefit from good planning, however. For instance, some employees hired directly from college might be enrolled in short-term training programs until specific positions are open. Accurate human resource forecasting facilitates this type of arrangement and allows the batch approach to reap many of the advantages associated with the flow approach.

CENTRALIZATION OF PROCESSES

An additional aspect of planning and recruiting is the extent to which activities are centralized. In organizations that use centralized procedures, the human resource department is responsible for recruiting activities. In organizations that use decentralized procedures, individual departments and plants make and carry out their own plans.27

A primary benefit of centralized procedures is cost savings. Organizations with centralized processes tend to put more effort into planning ways to recruit employees through inexpensive means. With centralization, recruiting is carried out by members of the human resource department, who don't need to learn new details about the recruiting process and labor environment each time a position opens. These professionals also develop ongoing relationships with other businesses, such as newspaper advertising departments and employment agencies. On the whole, then, organizations with centralized procedures are more likely to benefit from human resource planning through forecasting of overall needs and having full-time professional recruiters on staff.

A potential problem with centralized recruiting is the distance it creates between new recruits and the people with whom they will actually work. Managers often blame the human resource department when new recruits don't become good employees. A primary advantage of decentralized procedures is thus the sense of ownership that they create. Managers and current employees involved in recruiting are more committed to helping recruits succeed when they have selected those recruits.

In practice, many organizations benefit from combining elements of centralized and decentralized procedures. Efficiency is created by using centralized resources to identify a pool of job applicants. Managers and other employees then become involved to make specific decisions. Good human resource planning provides a means of coordinating the actions of different parts of the organization. Planning also helps the various parts of the organization work cooperatively by identifying people who might be promoted or transferred across departments or plants.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

Who Searches for Jobs?

An important part of effective recruiting is understanding the needs, goals, and behaviors of people searching for jobs. In general, we can identify three types of people looking for work: people entering the workforce for the first time, people who have been in the workforce but are currently unemployed, and people who are currently employed but seeking a different job. Although these groups differ somewhat, they also have a number of things in common.

One characteristic that job seekers share is their tendency to mostly plan their activities.28 Thus, the things people do to find a job are rather predictable and can be explained by three processes:

- The first process, attitude formation, concerns feelings and emotions. People make an effort to find employment when they feel confident that they have what it takes to get a new job, when they find the search process interesting, and when others such as spouse and family members think it is a good idea.

- Attitudes and beliefs lead people to form specific intentions, which represent goals and plans for future action.

- Goals and intentions lead to actual job search behavior, which includes any actions aimed at finding employment. Typical job search behavior includes gathering information and visiting organizations.

People engage in job-seeking activities when they have clear goals based on their belief that doing certain things will improve their lives. Organizations can thus influence potential recruits by providing information that helps them form positive attitudes. Actions that communicate strong interest and caring are particularly beneficial. Clearly conveying the benefits of a particular job can also result in forming stronger intentions and goals. The exact nature of attitudes and goals is, however, somewhat different for different types of job seekers.

NEW WORKFORCE ENTRANTS

Most people enter the full-time workforce when they graduate from school—either high school or college. The job search activities of these new workforce entrants typically follow a sequence. The first stage in the sequence is a very intense and broad search of formal sources of information about many different opportunities. At this point, job seekers are looking at aspects such as whether openings exist, what qualifications are necessary, and how to apply. The second stage is more focused as the job seekers begin to search for explicit information about a small number of possibilities. Information in this stage often comes from informal contacts rather than through formal channels. The focus shifts from learning about job openings to finding out specific details about particular jobs. If a job seeker spends considerable time in the second stage but is unable to find a job, he or she will go back to the first stage and conduct another broad search.29

Take a moment to consider how knowledge of the job search sequence can guide your own current and future efforts. First, you should currently be working in the first stage and learning a lot about various opportunities, even if graduation is still a few years away. As you get closer to graduation, you will benefit from focusing your efforts and learning details about specific jobs in specific organizations. You should also develop informal channels of information such as relationships with current employees. These relationships provide insights that you cannot gain from sources such as formal recruiting advertisements and websites. As described in the “How Do We Know” feature, you will benefit in each of these stages from taking a proactive approach to finding a job.

How can knowledge about the job search sequence help organizations more effectively recruit? Since people entering the workforce search broadly in the beginning, organizations can benefit from finding ways to share positive messages that set them apart from other potential employers. The objective is to build positive impressions that influence attitudes and thereby guide future goals and actions. Normal marketing channels such as television and newspaper advertisements are helpful in this way. For instance, the Sports Authority chain of sporting goods stores has about 14,000 employees, many of whom became interested in working for them because of their positive brand image. Regular customers who have already developed a favorable view of the store can apply for jobs at in-store kiosks.30

Organizations can also benefit from making sure they provide methods of sharing informal information with people who have entered the second stage of the search process. In this second stage, potential employees benefit from contact with current employees, who can share information that helps potential applicants decide whether a specific job is right. This careful examination of potential fit is most critical for firms pursuing long-term relationships with employees, and so it is most appropriate for organizations using Loyal Soldier and Committed Expert HR strategies. Organizations with these strategies benefit from focusing their efforts on recruiting people who are just entering the workforce and have long careers ahead of them.

UNEMPLOYED WORKERS

Potential job recruits also include people who have previously been in the workforce but are currently unemployed. Much of the research in this area explores the negative attitudes associated with being unemployed. You can relate to the frustrations of these people if you have ever had trouble finding a job. Unemployed workers get depressed easily. They experience decreased mental and physical health, less life satisfaction, and increased marital and family problems.31

A consistent finding relating to job search for the unemployed is the importance of social support. People remain more optimistic, engage in more activities to find a job, and obtain better jobs when they feel strong social support from others.32 Like other types of job seekers, unemployed people are also more successful at locating work when they take a proactive approach, set goals, and actively look for jobs.33 Yet the strong negative emotions associated with being unemployed suggest that many potential employees become so frustrated that they stop looking for work. Organizations recruiting people from the unemployment ranks therefore benefit from actively seeking out and encouraging people who have been laid off from other jobs. Helping individuals regain a sense of self-worth and confidence can communicate interest and caring. Organizations with a Bargain Laborer HR strategy, which have a constant need for new employees who are willing to work for lower wages, may particularly benefit from recruiting unemployed people.

Another interesting development in the recruitment of unemployed workers is the movement toward internationalization. Organizations in many countries find it difficult to recruit enough workers to fill entry-level positions. For instance, hotel operators in Northern Ireland struggle to find enough people to work in jobs such as housekeeping and guest services. In fact, as many as 19 percent of jobs go unfilled in Northern Ireland hotels. Several hotels are addressing this problem by recruiting workers from other countries. Recruiting has attracted people from countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic, Latvia, and Lithuania. Although these workers are not technically unemployed in their home countries, they can find better work alternatives in Ireland. Taking an international approach to recruiting workers who are not yet employed in a particular country can thus be helpful in finding people willing to do entry-level jobs.34

WORKERS CURRENTLY EMPLOYED

The third group of potential job recruits includes individuals currently employed by other organizations. Some are actively seeking a change, and others are open to a move if a good opportunity arises. People who search for alternative jobs while still employed tend to be intelligent, agreeable, open to new experiences, and less prone to worry.35

Studies suggest that dissatisfaction with a current job is an important key for understanding why people accept new employment.36 In many cases, employed workers are open to taking new jobs because they have experienced some kind of undesirable change in their current positions. In other cases, people are willing to move because they have slowly become dissatisfied over time.37 In either situation, they are likely to move because their attitudes about their current jobs are not as positive as they would like. Changes in work conditions that create negative attitudes and make it more likely for people to leave their current jobs include an increased need to balance career and family demands, dissatisfaction with pay, and feelings that the organization is not moving in the right direction.38

So what can an organization do to increase its success in recruiting people who are already employed by other firms? One tactic is to direct recruiting messages to employees who have recently experienced negative changes in their work roles. Common signals of negative change at competitor organizations include announcements of decreased profitability, lower bonuses, and changes in upper management. A primary objective of recruiting in these cases is to help channel negative attitudes into a specific goal to seek a better job. The recruiting organization might help potential employees to form positive attitudes about moving to a new job and can do so by clearly communicating the fact that it will provide a superior work environment. An organization trying to recruit can also take steps to minimize the hassle of changing jobs.39 A constant need for people with highly specialized skills makes efforts to recruit people who are currently working elsewhere particularly important to organizations with Free Agent HR strategies.

Organizations that seek to hire workers from competitors should be careful to avoid talent wars. Talent wars occur when competitors seek to “poach,” or steal, employees from one another. An organization that believes a competitor is attempting to raid its talent might respond by working to make things better internally. Or it might instead attempt to retaliate against the competitor—for example, stealing some of the competitor's employees. Unfortunately, back-and-forth negative tactics often result in a war that is dysfunctional for both organizations. To reduce the risk of a talent war, organizations can avoid hiring batches of employees away from a competitor and making sure that employees recruited from competitors receive promotions rather than transfers to the same job.40

Talent wars

Negative competition in which companies attempt to hire one another's employees.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4

What Characteristics Make an Organization Attractive?

Of course, not all organizations are equally attractive employers. One way to think about differences in organizational attractiveness is to reflect on your choice of a school. Why did you choose to study at your current college or university? Was it because it was close to where you wanted to live? Was it because of a great academic program in an area you wanted to study? Was it because it was the least expensive alternative? Was it because you wanted to be with certain friends? Maybe it was because it provided you with a way to balance other aspects of your life, such as work and family. Or perhaps you just didn't have any other choice.

In a similar way, people choose jobs for a variety of reasons. Potential employees are often attracted to an organization because it provides a work opportunity in a place where they want to live.41 Why people choose to work for certain organizations is, however, complicated. Factors that influence an applicant's decision about whether to continue applying vary across the job search. Perceptions of fit with the position are critical at the time of application, recruiter behavior and organizational characteristics have a strong influence in the middle of the process, and characteristics of the specific job are given the most weight in the final job choice decision.42

Complicating the issue is the fact that what matters to one person may not matter to others. Look around your classes. Do you believe everyone chose the university for the same reasons? It is true that some qualities were probably important to most people, such as the ability to get a good education. Beyond that, however, different features were likely to be important to different people. Some might have based their choice on the location or on the social atmosphere. Once again, the choice of a work organization is similar. People with certain characteristics are more strongly attracted to some types of organizations than others. Obtaining enough high-quality employees is an increasingly difficult task for most organizations. This means that organizations can develop a competitive advantage by creating a place where people want to work. In order to better understand what makes organizations attractive places to work, let's first look at some of the general characteristics that people desire in their places of employment. We then further explore how certain types of people are attracted to certain types of organizations.

GENERALLY ATTRACTIVE CHARACTERISTICS

What organizations come to mind when you think about places where you will likely look for a job in the future? Job applicants often base their choices on characteristics such as familiarity, compensation, certain organizational traits, and recruiting activities.

Familiarity

Odds are pretty high that you would prefer searching for jobs in companies that are already somewhat familiar.43 Much of this familiarity comes from corporate advertising that showcases the organizations' products and services. Familiar firms have better reputations because people tend to remember positive things about them.44 People actively respond to recruiting efforts by companies with strong reputations. Job seekers are more likely to obtain additional information about these organizations and make formal job applications.

Familiar organizations don't benefit much from image-enhancing activities such as sponsoring events or placing advertisements that provide general information about working for them. Because people already have a generally positive image of familiar organizations, such activities are not necessary. In contrast, less well-known organizations can benefit from sponsorships, general advertising, and the like. These organizations must create positive attitudes before they can get people to take actions such as applying for positions. In short, companies with low product awareness benefit from image-enhancing activities like general advertisements and sponsorships, whereas companies with high product awareness benefit most from practices that provide specific information such as detailed job postings and discussions with actual employees.45

Organizations with a strong brand image thus have an overall advantage in recruiting. Their efforts to advertise their products and services provide them with a good reputation that helps them attract potential employees. They don't need to spend time and resources helping people become familiar with them. In contrast, the less well-known company needs to create an image as a generally desirable place to work.46

Compensation and Similar Job Features

Not surprisingly, compensation affects people's attitudes about an organization. People want to work for organizations that pay more.47 In general, people prefer their pay to be based primarily on their own work outcomes rather than on the efforts of other people. Most people also prefer organizations that offer better and more flexible benefits.48 Greater opportunities for advancement and higher job security are also beneficial.49

Organizational Traits

Organizations, like people, have certain traits that make them more desirable employers.50 Desirable organizations have an image of sincerity, kindness, and trust and have a family-like atmosphere that demonstrates concern for employees. Walt Disney, for example, is often seen as desirable employer. Another desirable organizational trait is innovativeness. People want to work for innovative organizations because they think their work will be interesting. Many job seekers see this trait in shoe manufacturers Nike and Reebok. Competence is also a desirable trait. People want to work for an organization that is successful. Microsoft, for example, is widely seen as highly competent. Organizations are better able to recruit when they are seen as trustworthy and friendly, as innovative, and as successful.51

Recruiting Activities

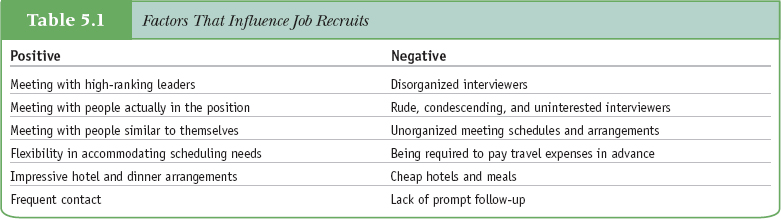

What an organization does during the recruiting process also matters. Particularly helpful is obtaining endorsements from people that job recruits trust. For instance, organizations are most successful recruiting on college campuses when faculty and alumni recommend them as good places to work.52 The interpersonal skill of recruiters also influences attitudes about an organization. Recruits enjoy the process more and are more likely to accept job offers when recruiters develop positive interactions with them.53 In contrast, as discussed in the “How Do We Know?” feature, long delays tend to decrease organizational attractiveness. Recruits, particularly those who are most qualified, develop an unfavorable impression when organizations take a long time to make decisions and fail to keep them informed about what is happening.54 In short, organizations are constantly making an impression on recruits as they carry out the recruiting process. Table 5.1 lists factors that influence job recruits.55

Source: Information from Wendy R. Boswell, Mark V. Roehling, Marcie A. LePine, and Lisa M. Moynihan, “Individual Job-Choice Decisions and the Impact of Job Attributes and Recruitment Practices: A Longitudinal Field Study,” Human Resource Management 42 (2003): 23–37.

FIT BETWEEN PEOPLE AND ORGANIZATIONS

The world would be a boring place if everyone wanted to work for the same type of organization. A number of studies suggest that people with different characteristics are likely to be attracted to different types of organizations. One example concerns the organization's size. Some job seekers prefer to work for large firms, while others prefer small firms.56 Another example relates to money. Even though people generally want to work for organizations that pay well, some people care more about money than others. In particular, people who describe themselves as having a strong desire for material goods are attracted to organizations with high pay.57 People who have a high need for achievement prefer organizations where pay is based on performance.58 Individuals who have high confidence in their own abilities also prefer to work in organizations that base rewards on individual rather than group performance.59

Some differences have been found between men and women. Men are more likely to be attracted to organizations described as innovative and decisive, whereas women tend to prefer organizations that are detail-oriented.60 People also like organizations whose characteristics are similar to their own personality traits. For instance, conscientious people seek to work in organizations that are outcome oriented, and agreeable people like organizations that are supportive and team-oriented. Individuals characterized by openness to experience prefer organizations that are innovative.61 The same desire for similarity is found in the realm of values. People who place a great deal of value on fairness seek out organizations that are seen as fair, people who have a high concern for others want to work for organizations that show concern, and people who value high achievement prefer a place with an air of success.62 The bottom line is that people feel they better fit in organizations whose characteristics and values are similar to their own. During the process of recruiting, potential employees also develop more positive perceptions of organizations whose recruiters appear similar to them.63

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 5

What Are Common Recruiting Sources?

Organizations use a variety of sources to find job applicants. Sources such as referrals from current employees are relatively informal, whereas sources such as professional recruiters are more formal. In this section, we consider the use of job posting, employee referrals, print advertising, electronic recruiting, employment agencies, and campus recruiting. Each method has its strengths and weaknesses, and certain methods also align better with particular HR strategies.

JOB POSTING

Recruiting people who already work for the organization is relatively easy. Internal recruiting is normally done through job posting, which uses company communication channels to share information about job vacancies with current employees. Historically, posting has used such tools as bulletin boards and announcements in meetings; today, most modern organizations use some form of electronic communication, such as websites and email messages. An effective job posting clearly describes both the nature of the duties associated with the position and the necessary qualifications.

Job posting

Using company communication channels to communicate job vacancies.

As you would expect, job posting is most appropriate for organizations adopting internal recruiting strategies. When the strategy is a Loyal Soldier HR strategy, job postings should be shared with a large number of people to facilitate movement among a variety of positions. For a Committed Expert HR strategy, the posting should be targeted specifically to those who have the expertise needed to move into relatively specialized roles.

EMPLOYEE REFERRALS

Employee referrals occur when current employees get their friends and acquaintances to apply for positions. Almost all organizations and job seekers rely on referrals to some extent. In many organizations, up to one third of new employees come through the referral process.64 A majority of human resource professionals also believe that employee referrals are the most effective method of recruiting.65 Referrals are thought to have at least four primary strengths: (1) Referrals represent a relatively inexpensive method of recruiting, (2) they are quicker than many other forms of recruiting, (3) people hired through referrals tend to become better employees who are less likely to leave the organization, and (4) current employees become more committed to the organization when they successfully refer someone.66

The first benefit, low cost, is sometimes questioned because organizations often pay bonuses to employees who make successful referrals. As described for Google, a typical bonus ranges from $1,000 to $2,000. This amount is, however, usually less than the cost of other recruiting methods, such as advertising and using recruitment agencies.67 Current employees are also in continuous contact with friends and acquaintances, which eliminates much of the time needed to plan and develop more formal recruiting processes. They also are in a better position to identify people who are ready to make job changes.

The informal nature of the referral process also makes it an effective method for identifying the best candidates. Current employees generally have accurate first-hand knowledge of the potential applicant's skills and motivation. This information can improve hiring decisions. Feelings of responsibility make it likely that employees will only refer people they are confident will succeed; they don't of course want to refer someone who will make them look bad. The informal information that employees share with the people whom they are referring can also serve as a realistic job preview, which helps reduce employee turnover.68

A study of call-center employees illustrates the benefits of finding employees through referrals. Highly successful call centers found 21 percent of their employees through referrals, whereas less-successful centers found only 4 percent of employees through this method.69 In addition, call centers that found more new employees through referrals had lower turnover.

As mentioned earlier, providing a referral also strengthens an employee's commitment to the organization. Some of this increased commitment derives from the current employee's feeling that his or her input is valued. The feeling of being appreciated is strengthened when a reward is offered for helping the organization.70 Employees also find it more difficult to say and believe bad things about the organization after they have convinced a friend to join them.71

Referrals are effective for organizations pursuing any HR strategy. For organizations pursuing a Bargain Laborer HR strategy, referrals help the organization inexpensively identify job candidates. Referrals help decrease turnover for organizations with either a Loyal Soldier or Committed Expert HR strategy. They can also be an effective part of a Free Agent HR strategy, because professional employees often have strong networks of acquaintances who have rare but needed skills. Table 5.2 lists ways to make employee referral programs more effective.72 Other keys to success include keeping things simple and communicating continuously.

Source: Information from Michelle Neely Martinez, “The Headhunter Within: Turn Your Employees into Recruiters with a High-Impact Referral Program,” HR Magazine 46, no. 8 (2001): 48–55; Carroll Lachnit, “Employee Referral Saves Time, Saves Money, Delivers Quality,” Workforce 80, no. 6 (2001): 66–72.

PRINT ADVERTISING

Employment advertisements have historically been a major part of almost all newspapers. Newspaper advertising has the potential to reach a large number of people for a relatively low cost, making it potentially desirable for the Bargain Laborer HR strategy. General advertising in newspapers can also help build a positive reputation for the organization as a desirable place to work.73 Employment advertising in newspapers has, however, become less frequent as more people gain their information from online sources, and human resource professionals predict that use of newspaper advertising will decrease by as much as 40 percent in the near future.74

Focused recruiting messages can also be placed in more specialized publications. For instance, openings in technical fields such as engineering can be advertised in trade journals. This more focused approach helps reduce the costs associated with sending recruiting messages to people who are obviously unsuitable for the job. Advertising in specialized journals is potentially most helpful for organizations that pursue a Free Agent HR strategy.

ELECTRONIC ADVERTISING

Electronic advertising uses modern technology, particularly the Internet, to send recruiting messages. Although electronic communication is seen by applicants as somewhat less informative than face-to-face contact,75 organizations are rapidly increasing its use. Popular websites, such as Monster.com and Careerbuilder.com, include thousands of job postings that can be sorted in a variety of ways. Website visitors can look for jobs in certain geographic areas, for example, or can search for specific types of jobs regardless of location. Job seekers can post their résumés online. These websites also provide a number of helpful services, such as guidance in building a good résumé.

Electronic advertising

Using electronic forms of communication such as the Internet and email to recruit new employees.

Company websites are yet another avenue for electronic advertising. Almost all large companies have a career website. Using the company website to recruit employees is relatively inexpensive and can be carefully controlled to provide information that conveys a clear recruiting message. Effective messaging occurs when organizations include racially diverse examples in their recruiting messages, which has been shown to be especially helpful for increasing minority perceptions of organizational attraction.76

Of course, not all websites are equally effective. Some are very basic and provide only a list of job openings. More advanced websites include search engines for locating particular types of jobs, as well as services that send email messages notifying users when certain types of jobs appear. An analysis of career websites for Fortune 100 companies found that most support online submission of résumés. A majority of sites also provides information about the work environment, benefits, and employee diversity.77

Decreased cost is the most frequently identified benefit of electronic recruiting. Electronic advertising is also much faster than most other forms of recruiting. Job announcements can be posted almost immediately on many sites, and information can be changed and updated easily. Another potential advantage of electronic advertising is the identification of better job candidates. Many organizations report that the applicants they find through online sources are better than the applicants they find through newspaper advertising. Responding through electronic means almost guarantees some level of familiarity with modern technology. In particular, applicants for midlevel positions seem to favor online resources over newspapers.78

Perhaps the biggest problem associated with electronic advertising is its tendency to yield a large number of applicants who are not qualified for the advertised jobs. Clicking a button on a computer screen and submitting an online résumé is such an easy process that people may do it even when they know they are not qualified for the job. In fact, one survey found that less than 20 percent of online applicants meet minimum qualifications. A potential solution is to use software that evaluates and eliminates résumés that do not include certain words clearly suggesting a fit with the job.79 This computer screening could, however, eliminate some applicants who might actually be able to do the job. Another recently advocated strategy is thus to customize recruiting by providing applicants clear information about their potential fit with a specific job. Applicants who learn through electronic communication that their characteristics don't fit a job or organization are less likely to waste time and effort by applying, suggesting that interactive technology may be a key to decreasing the number of unqualified applicants.80 In particular, websites that combine customization with nice-looking features (color, font size, spacing) are effective at screening out weak applicants.81 Table 5.3 lists tips for increasing the effectiveness of online recruiting.82

In the end, electronic recruiting can be effective for organizations pursuing any HR strategy. Targeted recruiting strategies should provide clear descriptions of job qualifications and should be placed on sites visited primarily by people likely to have the needed skills and abilities. Broad recruiting strategies should cast a wider net and can benefit from the large number of people who visit commercial recruiting sites. As shown in the “Technology in HR” feature, companies can also use electronic communication to stay in touch with recruits.

EMPLOYMENT AGENCIES

Each state in the United States, has a public employment agency, which is a government bureau that helps match job seekers with employers. These agencies have local offices that normally post information about local job vacancies on bulletin boards and provide testing and other services to help people learn about their strengths and weaknesses, as well as different careers that might fit their interests. Many offices help employers screen job applicants. State agencies also maintain websites for electronic recruiting. Links to the various state job banks can be found at CareerOneStop (careeronestop.org), which is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Labor and also offers career exploration information.

Public employment agency

Government-sponsored agency that helps people find jobs.

Sources: Information from V. Michael Prencipe, “Online Recruiting Simplified,” Sales and Marketing Management 160, no. 4 (2008): 15–16; Rita Zeidner, “Making Online Recruiting More Secure,” HR Magazine 52, no. 12 (2007): 75–77; Anonymous, “Ideas for Improving Your Corporate Web Recruiting Site,” HR Focus 83, no. 5 (2006): 9.

Many state employment agencies seek to help people transition from unemployment. They also focus on helping young people move from high school into the workforce. These agencies are therefore particularly helpful for recruiting employees into entry-level positions. Almost all services of public employment agencies are free to both organizations and job seekers. Since most people who seek employment through public agencies do not have specialized education and skills, these agencies are most helpful for companies engaged in broad skill recruiting.

A private employment agency is a professional recruiting firm that helps organizations identify recruits for specific job positions in return for a fee. Kelly Services, for example, provides placement services for approximately 560,000 people annually in areas including office services, accounting, engineering, information technology, law, science, marketing, light industrial, education, healthcare, and home care.83 Another private agency is Korn/Ferry, which specializes in recruiting top-level executives. Such firms are sometimes referred to as headhunters, because they normally target specific individuals who are employed at other organizations.

Private employment agency

A business that exists for the purpose of helping organizations find workers.

Private recruiting firms provide direct help to organizations by identifying and screening potential employees for particular positions. They also serve as temporary staffing agencies by maintaining a group of workers who can quickly fill short-term positions in client organizations. In many cases, these temporary workers are eventually hired as full-time employees. The temporary staffing assignment works as a tryout for the job, which helps eliminate costs associated with hiring workers who then perform poorly.

Private employment agencies are frequently able to recruit people who are not actively seeking new positions. Executive recruiters, in particular, are known for their efforts to develop and maintain broad networks of people who are not actively seeking new jobs but who might be willing to move for the right opportunity. In addition, private agencies target people who have the specific skills for the job. Client organizations are presented with a short list of high-quality applicants, which makes the search process more efficient for them. Another advantage of using private agencies is the ability to remain anonymous. The name of the hiring firm is often not disclosed during early stages of recruiting. Such anonymity can be helpful if a high-profile employee's intention to leave has not been publicly announced or if the organization does not want competitors to know its staffing needs.

Because of their targeted approach, private employment agencies can be particularly helpful for organizations pursuing a Free Agent HR strategy. These firms require specific skills that are often rare and in high demand. In these circumstances, qualified applicants are most likely already employed.

A disadvantage of private employment agencies is cost. Most executive recruiters work on a contingency basis; that is, they are only paid when they find someone who accepts the position. The recruiting fee is usually based on the salary that will be paid to the new employee. Typical fees amount to more than 30 percent of the first year's salary; the normal fee for finding an executive is thus at least $50,000.

Because of the expense associated with private employment agencies, most organizations develop written contracts that carefully describe the relationship between the agency and the client firm. A good contract should cover a number of issues, such as a guarantee of confidentiality and amount of fees. The contract should also include an off-limits statement, which formalizes an agreement that the agency will not try to recruit the new employee for another organization within a specified amount of time (usually at least a year). Most contracts also contain clauses that clarify that the fee is paid only if the individual stays with the new organization for a minimum period of time.84

CAMPUS RECRUITING

The pharmaceutical firm Eli Lilly recruits many of its employees as they graduate from universities. In order to focus its efforts, Lilly targets specific universities for hiring in specific functional areas. A university that is particularly strong in accounting might thus be targeted only for accounting recruits. A different university might be a target only for human resource recruits. Focusing on a few key schools allows Lilly to build relationships that provide important advantages for obtaining the best possible employees. In many cases, Lilly also offers promising students summer internships.85

Campus recruiting usually involves a number of activities. Organizations that recruit successfully work hard to build a strong reputation among students, faculty, and alumni. Relationships are built through activities such as giving talks to student organizations and participating in job fairs. Although studies question the benefits, campus recruiting often includes hosting receptions that provide an informal setting where information about the organization can be shared. Managers and current employees attend these events and network with students.86

The most widely recognized aspect of campus recruiting is job posting and interviewing. Employers use campus career centers to advertise specific job openings. At the centers, students provide résumés and apply for jobs that interest them. Firms identify students who best match their needs and arrange oncampus interviews. Full-time recruiters and line managers (often alumni) then spend a day or two on campus conducting preliminary interviews. Students who are evaluated positively during the on-campus interview are usually invited to a second interview, which takes place at the organization's offices.

Internships also represent a major component of most campus recruiting programs, giving students an opportunity to gain important work experience while they are enrolled in school. Students who have been interns take less time to find a first position, receive higher pay, and generally have greater job satisfaction.87 Internships also help organizations develop relationships with potential recruits. Working over a number of months provides a realistic preview of the job, which helps both the individual and the organization to determine whether there is a good fit.

Campus recruiting is well suited for organizations pursuing a Committed Expert HR strategy. These organizations adopt a targeted approach to recruiting that helps them identify people with the skills necessary to perform specialized tasks, such as engineering and accounting. Campus recruiting also helps them meet their strategic objective of identifying people who are just beginning their careers. While campus recruiting can be expensive, cost is not a serious problem for organizations that are seeking to identify people who will spend long careers working for them.

How Is Recruiting Effectiveness Determined?

Some organizations are better at attracting excellent job candidates than their competitors are. These organizations use recruiting as a tool for ensuring that they have the best possible employees, which in turn improves their bottomline profitability.88 Effective recruiting is thus an essential part of good human resource management. Unfortunately, many organizations do not measure and track how well they are doing with regard to recruiting. These organizations are at a strategic disadvantage because they do not use readily available information to help them learn about areas where they can improve.

COMMON MEASURES

Common measures of recruiting effectiveness include assessments of cost, time, quantity, and quality.89 Cost measures include the money paid for advertising, agency fees, and referral bonuses, and should also include travel expenses for both recruiters and recruits, as well as salary costs for people who spend time and effort on recruiting activities. Failure to include the salary expenses of both full-time recruiters and managers who spend time doing recruiting often leads to substantial underestimates of true cost.

Cost measures

Methods of assessing recruiting effectiveness that focus on expenses incurred.

Time measures assess the length of the period between the time recruiting begins and the time the new employee is in the position. Estimates suggest that the average time to fill a position is 52 days.90 During this period, the position is often open, and important tasks are not being done. In many cases, the performance of other employees also suffers because they spend time on activities that the new employee would perform if the position were filled. These factors suggest that an important objective of recruiting is to fill positions as quickly as possible.

Time measures

Methods of assessing recruiting effectiveness that focus on the length of time it takes to fill positions.

Quantity measures focus on the number of applicants or hires generated through various recruiting activities. Common measures include number of inquiries generated, number of job applicants, and number of job acceptances. These are measures of efficiency, and they provide information about the reach of recruiting practices. Recruiting is generally seen as more effective when it reaches a lot of potential applicants.

Quantity measures

Methods of assessing recruiting effectiveness that focus on the number of applicants and hires found by each source.

Quality measures concern the extent to which recruiting activities locate and gain the interest of people who are actually capable of performing the job. In most cases, measuring quality is more important than measuring quantity. Typical measures include assessments of how many applicants are qualified for the job, as well as measures of turnover and performance of the people hired.

Quality measures

Methods of assessing recruiting effectiveness that focus on the extent to which sources provide applicants who are actually qualified for jobs.