How Can Strategic Employee Compensation Make an Organization Effective?

Employee compensation is the process of paying and rewarding people for the contributions they make to an organization. A major part of compensation, of course, is the amount of money employees take home in their paychecks, but there are other important aspects as well. Compensation includes benefits such as insurance, retirement savings, and paid time off from work. Employees' positive feelings that come from working at a particular place are also sometimes seen as a form of compensation. In a broad sense, compensation thus represents the total package of rewards—both monetary and psychological—that an employee obtains from an organization. However, in practice we usually think of compensation as the economic rewards and benefits that an organization gives to its employees.

Employee compensation

The human resource practice of rewarding employees for their contributions.

Good compensation practices offer many advantages. Companies offering good pay and benefits attract better employees.1 Once hired, employees are more likely to stay with an organization if they feel they are paid well.2 A good incentive system communicates expectations and provides guidance so that employees understand what the organization wants from them. Paying people more when they contribute more increases motivation, which in turn leads to higher performance.3 Linking pay to performance is particularly helpful in encouraging people to produce a higher quantity of goods and services.4 In short, effective compensation practices motivate employees to do things that help increase an organization's productivity.

The benefits of effective compensation can be seen in the success of Marriott International, Inc. Beginning as a root beer stand in 1927, the company has grown into an international hospitality corporation that operates several hotel chains, including Courtyard, Fairfield Inn, Residence Inn, and Marriott Hotels & Resorts. A basic motto at Marriott is “If we take care of our associates, they'll take care of our guests.”5 Leaders in the company note that workers shopping for a job have choices similar to hotel guests shopping for a place to stay. Attracting and taking care of associates—or employees—is accomplished through compensation practices that build a culture of loyalty and high performance.

A major problem faced by Marriott and others in the hospitality industry is finding people who are willing to work in entry-level jobs such as house-keeping and food service. Education requirements for these jobs are not high, and many of the positions require difficult physical labor. People working in such conditions often find it difficult to feel strong commitment toward a specific employer. Turnover in the hospitality industry is therefore high. This makes it difficult for hotels and restaurants to obtain a stable workforce that creates a competitive advantage.

Marriott develops competitive advantage by taking a systematic approach to compensation that reduces employee turnover. The company obtains and analyzes a great deal of data to determine why employees leave. Human resource professionals then explore changes that can improve the chances of keeping good employees. For instance, by examining when people quit, Marriott learned that people are much less likely to leave once they become eligible for benefits such as health insurance and retirement savings plans. When they recognized this pattern, leaders at Marriott changed their compensation practices so that employees do not have to wait as long before becoming eligible for benefits. Having people wait to become eligible for benefits, which was meant to reduce labor costs, actually cost the company money due to increased employee turnover. Analyzing employee preferences also revealed that workers were most likely to remain loyal when they were given the opportunity to work some overtime each week. Being required to work more than 10 hours overtime per week, however, caused some workers to leave. Marriott thus decided to give employees an opportunity to work a moderate amount of overtime, thereby increasing employee satisfaction and retention.6

A systematic review of Marriott practices also revealed that each of the hotel chains operated independently. Compensation practices for employees working at a Courtyard were often different from practices for employees working at a Residence Inn, even though the two hotels were located in the same geographic area. As a result, employees thought of themselves as working for a specific chain rather than for the Marriott Corporation. Employee movement between hotel chains was limited, which reduced opportunities for promotion.

In response to this problem, Marriott adopted a market-based pay approach, which seeks to create a wage structure where people are paid fairly in comparison to what they could earn doing a similar job for another company in the specific geographic area. Thus, the pay for someone working in housekeeping at Residence Inn should be similar to the pay for someone working at Fairfield Inn, though the pay level for housekeepers in New York may be quite different from the pay level for housekeepers in Kansas. One benefit of moving to market-based wages has been greater movement of employees between chains. Having more employees who have worked at a variety of different hotel chains within Marriott has increased instances in which employees encourage their current customers to stay at other Marriott hotels.7

Market-based pay

A compensation approach that determines how much to pay employees by assessing how much they could make working for other organizations.

Another important practice at Marriott has been to move responsibility for compensation away from the human resource department. Individual line managers now have the primary responsibility for determining each employee's pay. Human resource department rules are deemphasized. The pay range for each job is placed in a broad band that provides guidance for different levels of compensation. Managers have a good deal of flexibility to decide where in the band to locate the pay for each employee. This allows managers to take into account the pay for other work opportunities in the area, as well as the qualifications and performance of the particular employee.8

As a whole, Marriott's compensation practices have developed a culture that rewards high performance. Not only does Marriott tend to pay more than its competitors, but it also differentiates more between high and low performers. Fewer people get paid at the top of the scale, but the overall pay is much higher for those who do. Truly exceptional performers thus make more than others and are more likely to continue working at Marriott. The company also recognizes outstanding performance with rewards such as trips and merchandise.9

Marriott's systematic approach to compensation, which includes pushing decisions to line managers and emphasizing greater pay for higher performance, plays an important part in the company's success. Simplifying procedures and having managers more involved increases the likelihood that employees believe they are paid fairly. These practices help Marriott continue to be ranked as one of the best places to work.10 Such a satisfying work experience helps reduce turnover, saving Marriott millions of dollars each year.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

How Is Employee Compensation Strategic?

Similar to other aspects of human resource management, compensation practices are most effective when they fit with an organization's overall HR strategy. In short, pay practices need to fit the broader human resource strategies first described in Chapter 2. As you know by now, these broad HR strategies vary along two dimensions: whether their labor orientation is internal or external and whether the company competes through cost or differentiation.

EXTERNAL VERSUS INTERNAL LABOR

Organizations choosing an external labor orientation frequently hire new employees, and these employees are not expected to form a long-term attachment to the organization. The lack of long-term commitment makes compensation particularly important. In fact, compensation is the primary factor in these employees' decisions about where to work. Current and potential employees frequently compare the organization's compensation packages with packages offered by other employers. Employees' perception of external equity—which concerns the fairness of what the company is paying them compared with what they could earn elsewhere—are critical in such employment relationships. People who see a lack of external equity become dissatisfied and choose to work somewhere else. This means that organizations with an external labor orientation must frequently assess how their compensation compares with the compensation offered by other organizations.11

External equity

Employee perceptions of fairness based on how much they are paid relative to people working in other organizations.

Organizations with an internal labor orientation seek to retain employees for long periods of time. These organizations encourage employees to stay by providing security and good working conditions, which are emphasized more than money.12 Employees become attached to the organization and are less likely to compare their compensation with the compensation they believe they could earn elsewhere. Instead, these employees compare their compensation with that of their coworkers. Employees' perceptions of internal equity—their beliefs concerning the fairness of what the organization is paying them compared with what it pays other employees—become critical. Internally oriented organizations also use long-term incentives to reward employees who stay with them for long periods.

Internal equity

Employee perceptions of fairness based on how much they are paid relative to others working in the same organization.

DIFFERENTIATION VERSUS COST STRATEGY

Organizations following a differentiation strategy seek high-performing employees who create superior goods and services. Compensation is used to encourage risk taking. For example, companies like 3M reward rather than punish employees who pursue uncertain products and ideas, even if they fail. Organizations with differentiation strategies also pay some employees much more than others. Success depends a great deal on outstanding contributions from a few individuals, so these organizations reward high performance by paying excellent performers substantially more than low performers. The result is substantial spread between the pay of high contributors and the pay of low contributors.13

In contrast to differentiation, a cost strategy requires organizations to adopt compensation practices that reduce labor expenses. Employees are usually paid fixed salaries that do not increase as performance improves. Thus, there is very little variation in pay between high and low performers. Emphasizing efficiency and tight coordination results in standardization, which is often accomplished by treating all employees the same. The value of a high performer is not substantially greater than the benefit of an average performer, so compensation is used to develop feelings of inclusion and support from the organization.

ALIGNING COMPENSATION WITH HR STRATEGY

Combining differences in internal and external pay with differences in cost and differentiation results in the grid shown as Figure 11.1. The horizontal dimension represents differences associated with cost and differentiation. Here, the major difference concerns the extent to which high performers are rewarded differently than low performers.14 A differentiation HR strategy is associated with variable rewards, which have the overall goal of spreading out compensation so that high performers are paid more than low performers. A cost reduction strategy is associated with uniform rewards and is aimed at providing consistent compensation so that employees are treated the same regardless of differences in performance.15

Variable rewards

A reward system that pays some employees substantially more than others in order to emphasize differences between high and low performers.

Uniform rewards

A reward system that minimizes differences among workers and offers similar compensation to all employees.

The vertical dimension of Figure 11.1 represents the type and length of the desired relationship between employees and the organization. One type of relationship is relational commitment. Relational commitments are based primarily on social ties rather than monetary incentives. Employees in this type of relationship work for an organization over time because they feel a sense of belonging. The organization uses compensation to build a sense of camaraderie and support.

Relational commitment

A sense of loyalty to an organization that is based not only on financial incentives but also on social ties.

Another type of relationship is transactional commitment. Transactional commitments are based primarily on financial incentives. In this type of relationship, employees are motivated by the short-term rewards they receive. Management uses compensation to encourage individuals to make outstanding contributions, but no one expects employees to develop a long-term relationship with the organization.16

Transactional commitment

A sense of obligation to an organization that is created primarily by financial incentives.

In Chapter 12, we will look at specific pay practices that fit particular human resource strategies. Here, we review broad differences between the goals of the four types of compensation.

Figure 11.1 Strategic Framework for Employee Selection.

Bargain Laborer Compensation

Perhaps you or a friend of yours has worked as a bagger in a grocery store. Most employees working in this role do not expect a long-term career. There is also little difference in the amount paid to high- and low-performing baggers. This type of compensation is most often associated with the Bargain Laborer HR strategy. As explained in Chapter 4, an extreme cost reduction strategy requires consistent contributions from all employees, which reduces the need to recognize high performance with additional compensation. Pay levels are set at the lowest level that allows the organization to attract enough workers, and there is a clear understanding that employees may leave if they receive better offers. Given that most employees working in these organizations have low-paying jobs, many workers can be expected to believe that their pay is lower than it should be. An important aspect of compensation in these organizations is thus developing fair processes and uniform practices that increase perceptions of fairness.

Loyal Soldier Compensation

The Loyal Soldier HR strategy also seeks to reduce costs, but the emphasis is on building a stable long-term workforce. Emphasizing low labor expenses and encouraging average rather than outstanding performance once again create a setting where high and low performers are treated similarly. However, the long-term orientation requires that compensation be used as a tool to bind employees to the organization. An example might be a community school district that employs a number of teachers and secretaries. Limited funding combined with the desire for stability will often result in the school district providing similar rewards to all employees while building a sense of commitment to the organization.

With the Loyal Soldier strategy pay increases are usually linked to time with the organization. Employees are rewarded for remaining loyal and not leaving to accept positions with competitors. Cooperation among employees, as well as a feeling of solidarity, is enhanced through compensation structured to decrease differences between high and low performers. Procedures that allow employees to express concerns about unfairness are also important. Longterm forms of compensation other than salary, such as health insurance and retirement benefits, are particularly helpful in building the employee commitment that is necessary for success with the Loyal Soldier HR strategy.

Free Agent Compensation

Compensation is the primary source of motivation for employees working in organizations with a Free Agent HR strategy. These organizations provide strong monetary incentives for high performers. A good example is a technology consulting firm. Highly skilled employees join and remain with a firm specifically because they receive high wages. Because organizations pursuing a Free Agent HR strategy need high performers with somewhat rare skills, they must pay more than other employers. Paying top performers within the organization more than low performers also attracts more productive people to apply for jobs.17 Short-term salary and bonuses are emphasized more than future rewards, such as retirement savings. Top performers are paid well, and individuals who succeed at risky ventures receive substantial rewards.

Employees in Free Agent organizations usually have opportunities to work for many possible employers, so an individual's salary is based primarily on what he or she would be worth to other organizations. The result is highly flexible compensation practices. Often, new employees are paid much more than employees who have been working at the organization for years in a similar position—a situation known as salary compression.

Salary compression

A situation created when new employees receive higher pay than employees who have been with the organization for a long time even though they perform the same job.

Committed Expert Compensation

Organizations pursuing a Committed Expert HR strategy also use compensation to reward high performers, but at the same time they strive to build longterm commitment. Management sets high goals for employees, and those who reach the goals are paid more than those who do not. Thus, people doing the same job are often paid very different amounts. An example of such strategy and compensation is a medical research and development laboratory. High performing researchers are paid more than low performers, but the need for long-term inputs also necessitates compensation practices that bind employees to long-term careers.

Overall, compensation in Committed Expert organizations is set at a level that is high enough to attract people with the most desirable skills. Because of their relatively high levels of expertise and skill, employees working for these organizations expect to receive higher wages than people working for other organizations. As long as the organization communicates its policies clearly and fairly, paying the best employees more than others helps retain top performers.18 Turnover is also reduced by offering long-term incentives such as retirement benefits and stock options. Top performers need to receive immediate rewards that recognize their contributions, but they must also receive long-term incentives that bind them to the organization for a number of years.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

How Does Compensation Motivate People?

Underlying the compensation strategies just discussed is the assumption that pay can be used to motivate employees. How does money motivate people? Several theories explain why people react to pay as they do. These theories, which are grounded in psychology and economics, provide principles that can be used to develop effective compensation practices. We discuss several theories in this section, but first we provide some background on the concept of motivation.

Motivation can be defined as a force that causes people to engage in a particular behavior rather than other behaviors. More specifically, motivation is represented by three elements: behavioral choice, intensity, and persistence.19 Each element, in turn, requires a decision:

Motivation

The sum of forces that cause an individual to engage in certain behaviors rather than alternative actions.

- Behavioral choice involves deciding whether to perform a particular action.

- Intensity concerns deciding how much effort to put into the behavior.

- Persistence involves deciding how long to keep working at the behavior.

As a student, you encounter each of these choices every day when you demonstrate whether you are motivated to do homework. The first step in showing motivation is to choose to spend time on schoolwork rather than other activities, such as watching television or playing sports. Once you have decided to spend time doing homework, you must next decide how hard you will focus on the work you are doing. Higher motivation is shown when you work continuously with maximum effort rather than taking frequent breaks and thinking mostly about other things. The final aspect of motivation is persistence, or how long you will keep at the task. You show low motivation if you work only for a few minutes and high motivation if you work for several hours. In sum, you show high motivation when you choose to do your homework rather than something else, when you pursue your homework with high intensity, and when you persist in doing it for a long period of time. Similarly, employees show high motivation by choosing to exert maximum effort to perform critical work tasks for a long period of time.

THEORIES OF MOTIVATION

Every organization wants to motivate its employees. Organizations want employees to engage in behaviors that will lead to success, and they want them to pursue desirable behaviors with intensity and persistence. How can organizations use compensation to meet these goals? Principles from various motivation theories explain how compensation practices can provide motivation. Here, we discuss five theories: reinforcement theory, goal-setting theory, justice theory, expectancy theory, and agency theory.

Reinforcement Theory

Would performance in your human resource class improve if your professor offered cash to the students who scored highest on a test? Although such a motivational tactic might become expensive, the performance of most students—particularly those who considered themselves the smartest and most likely to get the cash reward—would improve.

Using a reward such as money to encourage high performance is consistent with reinforcement theory. This theory, which comes from the field of psychology, holds that behavior is caused by chains of antecedents and consequents. Antecedents are factors in the environment that cue someone to engage in a specific behavior. For instance, the smell of fresh-baked apple pie might serve as an antecedent that encourages a person to eat. Consequents are results associated with specific behaviors. Antecedents and consequents are linked together because the antecedent causes people to think about the consequent. For example, one consequent of eating apple pie is the pleasurable feeling it gives you. Thus, the good smell motivates you to eat the pie because it reminds you of the pleasure associated with the taste. Of course a behavioral consequent can be negative, as when eating too much pie makes you feel sick. When associated with compensation, though, the core idea of reinforcement theory is that people will engage in the behaviors for which they are rewarded. Furthermore, cues in the environment can help focus attention on the rewards that come after the completion of specific behaviors.20

Reinforcement theory

A psychological theory suggesting that people are motivated by antecedents (environmental cues) and consequents (rewards and punishments).

One important principle of reinforcement is contingency. This principle tells us that a consequent motivates behavior only when it is contingent—that is, when it depends on the occurrence of the behavior. Contingency suggests that a reward should be given if, and only if, the desired behavior occurs. Otherwise, the potential reward loses the ability to motivate. Think about a parent who tells a child that he can have a cookie if he cleans his room. The child fails to clean the room, but the parent gives him the cookie anyway. According to the principle of contingency, the child will not be motivated to clean his room in return for a cookie in the future. The cookie has lost its motivational power.

Contingency

A reinforcement principle requiring that desirable consequents only be given after the occurrence of a desirable behavior.

In a similar way, pay motivates performance only when it is contingent on specific behaviors and outcomes. A key principle from reinforcement theory is thus that compensation should be based on performance so that better performers receive higher pay. The practice of allocating pay so that high performers receive more than low performers is known as pay-for-performance. As described in the “How Do We Know?” feature, employees whose pay is contingent generally perform better than employees whose pay is not contingent.21 Linking pay to performance can be particularly beneficial when it is part of an overall program of performance assessment, goal setting, and feedback.22

Pay-for-performance

Compensation practices that use differences in employee performance to determine differences in pay.

Goal-Setting Theory

Does setting a goal to achieve a certain grade in a class help you to perform better in that class? The simple answer is yes. The potential value of setting specific goals is highlighted in many studies showing that people who set goals do indeed perform better.23 Goal-setting theory is grounded in cognitive psychology and holds that behavior is motivated by conscious choices.24 Goals improve performance through four specific motivational processes:25

Goal-setting theory

A psychological theory suggesting that an individual's conscious choices explain motivation.

- Goals focus attention away from other activities toward the desired behavior. This effect is seen, for example, when a long-distance runner sets herself a goal to run a marathon in a certain time. Because of this goal, the runner is likely to spend more effort on running and less on other activities.

- Goals get people energized and excited about accomplishing something worthwhile. In our example, the runner's goal provides her with a vision of accomplishing a difficult task. This sense of vision and potential accomplishment builds excitement that increases her intensity during workouts.

- People work on tasks longer when they have specific goals. The runner's goal encourages her to be more persistent and not give up when facing setbacks such as fatigue or injury.

- Goals encourage the discovery and use of knowledge. Thus, the runner's goal might encourage her to investigate and learn training tips and race strategies. In sum, having a goal can improve performance by focusing attention, increasing intensity and persistence, and encouraging learning.

If goals are to act as effective motivators, they must be achievable.26 Suppose the goal of the runner in our earlier example was to run a marathon in under three hours. Running a marathon in this amount of time is beyond the skill of most people, no matter how hard they train. Having a goal that is nearly impossible to reach may actually harm performance by building a sense of frustration. Goals should thus be combined with effective selection and training practices to ensure that employees develop the needed skills.

Goal setting in work organizations can be combined with compensation in a number of ways.27 One obvious method is to offer a difficult goal and provide a bonus only to those who achieve it. This has the benefit of encouraging employees to really stretch and put forth their best effort. A problem with providing a reward only to individuals who achieve the so-called stretch goal is that many employees will barely miss the goal and will then become frustrated.

Another method of linking goals and compensation is to provide incremental rewards for people who achieve progressively higher goals. In this case, employees who achieve an initial, easy goal receive small rewards. Those who go on to achieve more difficult goals receive somewhat larger rewards, and those who accomplish the stretch goal receive rewards that are still larger. This incremental method can encourage everyone to try harder, even those who don't think they can achieve the highest goal. The problem is that some are satisfied with the small rewards, and fewer people may put forth their maximum effort to achieve the highest level of performance.

A third method of combining goals with compensation is to establish a difficult goal and then decide on the amount of the reward after performance has occurred. This method allows the manager to take into account factors such as how close the employee came to the goal, how hard the employee appeared to work, and whether environmental conditions had an effect on the employee's ability to meet the goal. Unfortunately, waiting to decide on the amount of the reward until after the performance has occurred can sometimes seem unfair. Accurately determining how much to pay can also be difficult if the manager doesn't know the whole set of circumstances that affected the employee's opportunity to achieve the goal.

Justice Theory

Suppose you studied much harder for an exam than a friend, only to end up getting a lower grade than the friend. Would you consider that outcome unfair? Judgments about the fairness of outcomes in relation to efforts are at the core of justice theory. This psychological perspective holds that motivation depends on beliefs about fairness.

Justice theory

A psychological theory suggesting that motivation is driven by beliefs about fairness.

An early form of justice theory was equity theory, which is illustrated in Figure 11.2. According to equity theory, people compare their inputs and outcomes to the inputs and outcomes of others.28 Employees are particularly prone to comparing themselves to others whom they perceive as being paid the most, suggesting that comparisons may be biased.29 Nevertheless, equity theory suggests that a computer programmer is motivated by the comparisons that she makes between herself and other people. She first assesses how much effort and skill she puts into her job relative to how much she is paid. She then compares this with how much effort and skill others put into their jobs relative to how much they are paid. She compares the ratio of her inputs and outcomes with the ratios for others. She feels inequity if she believes that she works harder and contributes more to the organization than another programmer who is paid the same salary.

Equity theory

A justice perspective suggesting that people determine the fairness of their pay by comparing what they give to and receive from the organization with what others give and receive.

Employees who perceive inequity might try a number of things to make their pay seem fairer. On the one hand, they may decrease their inputs to the organization—for example, by spending less time at work and putting forth less effort. On the other hand, they might try to increase the outcomes they receive from the organization. Asking for and receiving a pay raise is one way to increase outcomes. Equity theory has also been used to explain employee theft. People who perceive inequity are more likely to steal from their employers in an attempt to increase their outcomes.30 People who continue to feel inequity are likely to leave the organization and start working somewhere else.31

Figure 11.2 Equity Theory.

Equity theory is an example of what is known as distributive justice. Distributive justice is concerned with the fairness of outcomes. In terms of compensation, distributive justice focuses on whether people believe the amount of pay they receive is fair. A different form of justice is procedural justice, which is concerned with the fairness of the procedures used to allocate outcomes. The focus here is on the process used to decide who gets which rewards.

Distributive justice

Perceptions of fairness based on the outcomes (such as pay) received from an organization.

Procedural justice

Perceptions of fairness based on the processes used to allocate outcomes such as pay.

Although some people are simply prone to see everything as unfair,32 most people consider a number of issues when judging whether an organization's compensation procedures are fair. Not surprisingly, people with higher wages tend to see pay as more fair.33 Employees who are near the bottom of the pay scale are concerned about the minimum amount they will make, whereas employees near the top of the scale care more about the maximum they can make.34 Overall, compensation strategies tend to be seen as more fair when they are free of favoritism, encourage employee participation in decisions about how rewards will be allocated, and allow appeal from people who think they are being mistreated.35 Compensation procedures are also more likely to be seen as fair when they are based on accurate performance appraisal information.36 In the end, employees who see the organization as more fair tend to have higher levels of satisfaction and commitment, as well as higher individual performance.37

Expectancy Theory

Expectancy theory offers a somewhat complex view of how individuals are motivated. The theory proposes that motivation comes from three beliefs: valence, instrumentality, and expectancy.38 The overall framework is shown in Figure 11.3

Expectancy theory

A psychological theory suggesting that people are motivated by a combination of three beliefs: valence, instrumentality, and expectancy.

Figure 11.3 Expectancy Theory.

- Valence is the belief that a certain reward is valuable. The concept of valence is an important reminder that not everyone is motivated by the same thing. Suppose, for example, that a company offers to send its highest performing employees on an all-expenses-paid trip to a Caribbean resort. This reward may be highly valued by some employees but may be undesirable to others. Only those who value the vacation will be motivated to do what is required to earn it.

Valence

The value that an individual places on a reward being offered.

- Instrumentality is the belief that a reward will really be given if and only if the appropriate behavior or outcome is produced. Obviously, if employees don't believe that they will receive the promised reward even if they perform the required actions, they will not be motivated by the reward.

Instrumentality

The belief in the likelihood that the reward will actually be given contingent on high performance.

- Expectancy concerns people's belief that they can actually achieve the desired level of performance. This belief is based in part on people's assessment of their own skills and abilities. Motivation is higher when people believe they are capable of high performance.39 Expectancy belief may also be based in part on an assessment of whether the environment will create obstacles that limit performance. Motivation is reduced when people believe that things such as lack of materials and equipment will keep them from being able to perform well.40

Expectancy

An individual's belief that he or she can do what is necessary to achieve high performance.

According to expectancy theory, all three desirable beliefs must be present for motivation to occur. For example, a sales representative may value a high commission (valence) and may believe that she will receive it if she closes a specific sale (instrumentality). However, she won't be motivated to pursue the sale unless she really believes she can do something that will influence the client to make the purchase (expectancy). A food server in a restaurant may believe that he is able to provide great service (expectancy), and he may value high tips (valence), but if he doesn't believe a certain customer will leave a tip even if his performance is excellent (instrumentality), he will not be motivated to give that customer great service.

Agency Theory

Imagine that a child is sent to the store to buy laundry soap for his family. He is given $5 and told that he can spend any leftover money on candy. At the store, he finds two cartons of laundry soap. A small box that has been damaged is priced at $2. A large box that is intact is priced at $4. Which box will the child choose? On the one hand, he would like to buy the $2 box of soap and spend $3 on candy. On the other hand, the parent will be better served if the child buys the $4 box of soap.

In this scenario, we can look at the parent as the principal and the child as the agent. An agent is someone who acts on behalf of a principal. Thus, a company's employees are agents of the owners of the company, who are the principals. When the company is a publicly held corporation, the owners are the shareholders. An interesting feature of the agent–principal relationship is that the interests of agents are not necessarily the same as the interests of principals, as you can see in our laundry soap example. Agency theory suggests that we can gain insight into motivation by thinking about these differences.41

Agency theory

An economic theory that uses differences in the interests of principals (owners) and agents (employees) to describe reactions to compensation.

One area in which principals (owners or stockholders) have interests different from those of agents (employees) involves risk. The owners of a business might benefit from taking risks that grow the business at a very rapid pace. However, the risk associated with high growth may be undesirable for an employee who perceives that growth may create short-term problems and cause the employee to lose his or her job. In most cases, employees are not willing to share risk unless they can also share the potential for a bigger reward. This idea seems obvious if you think about risk in terms of earning wages. Suppose you agree to work in a sandwich shop for a week, and you get to decide how you will be paid. One choice is to get paid $400 for working 40 hours. The other choice is to get paid a percentage of total sales up to a certain level. With this option you may earn more than $400 if sales are good, but you may also earn less than $400 if sales are poor. Would you take the second option if the most you could possibly earn was $405? You probably would not accept the risk for such a small gain. But what if the most you could earn was $1,000?

If you chose the second option, you—the employee—would be bearing some of the risk for sales being high or low. You would most likely be willing to assume that risk only if you thought there was a chance for you to earn significantly more money. A general principle of agency theory is thus that wage rates should be higher when employees bear risk. For this reason, incentive plans that pay for performance are only effective when they give employees the opportunity to earn more than they could earn with fixed wages, such as hourly pay.42

Another important aspect of agency theory is the observation that principals and agents often don't have the same information. For example, think about large corporations. The owners—or stockholders—really know very little about the operations of the company. Agents—or managers—know a lot about the company, but the managers may be afraid to share information. Sometimes the information may make the agents look incompetent, suggesting that agents may not share all the different methods available for increasing profits. Owners may not be made aware of potential courses of action that might benefit them. Because owners can't always observe and effectively monitor the actions of employees, agency theory suggests that compensation practices must be structured so that employees are rewarded when they do the things that would be most desirable from the owners' perspective. A common example is giving stock options to top executives. With stock options, executives are rewarded when the stock price increases, which is assumed to be the preferred outcome of owners. Another example is to pay sales representatives with commissions so that they are rewarded for behavior that is aligned with the selling interests of the owners.43 A second general principle of agency theory beyond the first principle of risk a risk premium is thus that pay should be structured so that managers and employees receive higher rewards when they do the things that increase value for owners and shareholders.

LINKING MOTIVATION WITH STRATEGY

Each motivational theory has a slightly different focus, and in some cases concepts from one theory may be slightly at odds with concepts from another theory. Nevertheless, we can derive several basic principles from the motivational theories. These principles provide guidance for determining the best ways to motivate employees through the use of compensation practices.

Motivational principles can also be linked to the compensation strategies we discussed earlier in the chapter. (You may want to refer back to Figure 11.1 to review the strategic framework for employee compensation.) Recall that organizations using differentiation strategies tend to use variable compensation, while organizations focusing on cost tend to use uniform compensation. In general, then, organizations with variable compensation systems have a greater need for high motivation than organizations with uniform compensation practices. However, organizations with uniform compensation practices can also make use of key motivational principles. Table 11.1 summarizes how these key principles of motivation can guide compensation practices.

Variable Compensation and Motivation

Although some experts have suggested that linking pay to performance can reduce the joy of performing naturally interesting tasks,44 a majority of evidence shows that performance increases when high performers are paid more than low performers.45 The importance of pay for performance is therefore particularly high in organizations using variable compensation.

The strategic focus of differentiation makes high performance of employees critical for these organizations, and linking pay with performance is a strong motivator that encourages employees to put forth their best efforts. Organizations using variable compensation also benefit a great deal from making rewards contingent on achieving goals. As part of a Free Agent HR strategy, the organization can encourage exceptionally high performance by rewarding only individuals who reach the highest level of goal achievement. This practice provides a short-term incentive that pushes employees to exert maximum effort. Organizations pursuing a Committed Expert HR strategy can benefit from providing rewards to everyone who attains at least some level of goal achievement. This ensures that long-term employees don't get discouraged and quit if they fail to achieve a particularly high goal. Because employees working under variable compensation tend to assume greater risk, the overall level of compensation should thus be higher in organizations with Free Agent and Committed Expert HR strategies than in organizations with Bargain Laborer and Loyal Soldier strategies.

Understanding what reference group employees use in assessing the fairness of their pay is another important feature of variable compensation strategies. As part of the Committed Expert HR strategy, the primary reference group is people working in the same organization. With a Free Agent HR strategy, the primary reference group is people working in similar jobs at other companies. This distinction is important for understanding how compensation can be used to help an organization achieve a particular competitive strategy.

For instance, a professor who teaches in a medical school will likely believe that she is paid well when she compares her salary with the salaries of, say, professors of literature at her university. She may, however, not feel as good if her comparison group is highly paid medical school professors at other universities. How do these comparisons relate to competitive strategies? Comparisons with other professors at the same university are most critical if the university has a strategy of developing long-term relationships that focus on commitment rather than monetary rewards. Such long-term relationships are likely beneficial if the university is well established and seeking to defend its status. In contrast, comparisons with similar professors at other universities are most critical if the university has a strategy that benefits from short-term relationships. Such short-term relationships may be helpful if the organization is seeking to change, grow, or innovate.

Because organizations with a Committed Expert HR strategy are interested in developing ongoing relationships with employees, procedural fairness is particularly important for these organizations. Employees need to develop trust and feel that the organization supports them. Support often comes from feeling that the organization treats them fairly.46 Such perceptions are less critical in organizations with a Free Agent HR strategy.

Unfortunately, many variable compensation practices fail to motivate because the size of the potential reward is not large enough to influence behavior. Motivation will not increase, for example, if the organization offers a 2 percent salary increase to low performers and a 2.1 percent increase to high performers. In the terminology of expectancy theory, the amount of extra salary that can be earned doesn't have the valence required. This is a particular problem for many organizations that provide relatively small annual salary increases to a majority of employees. The amount of difference between a raise for a high performer and a raise for a low performer is just too small to motivate behavior.47

Uniform Compensation and Motivation

Uniform compensation practices are not as effective as variable compensation practices for encouraging high motivation. The goal with uniform practices is to create a culture of fairness and cooperation. Incentives that encourage high individual performance for some often lead individuals to sabotage and compete with coworkers, which in turn reduces the performance of the group as a whole.48 Rewards in organizations with uniform compensation are thus structured to reduce the emphasis on extreme individual performance.

In judging whether their pay is fair, employees in an organization with a Loyal Soldier HR strategy tend to compare themselves with employees working in the same organization. Such organizations usually seek competitive advantage through cost reduction, which means that they are unlikely to pay the premium wages required to secure employees who already possess rare skills and abilities. Rather than using high pay to buy talent, these organizations often use training to develop skills. Often, these skills are unique to a particular organization. For example, a consultant may become very skilled at understanding and resolving problems within a framework that is used only within the firm. The common framework increases the efficiency of his efforts, but his knowledge and ability would not be of much value to other firms not using the company-specific framework. For this reason, employees in cost-focused organizations often develop skills that have little value to other organizations, which decreases the likelihood that other organizations will be willing to offer them higher salaries. This has the effect of binding employees to the organization in a way that does not increase overall labor costs.

Organizations with a Bargain Laborer HR strategy seek to pay the lowest possible wages. Employees in these organizations are likely to move from organization to organization depending on which organization is willing to pay the most. Yet the relatively low skill level of these employees suggests that the wage rate will be near the minimum wage that is allowed under the law. We discuss the effect of minimum wage laws later in this chapter.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

How Is Compensation Level Determined?

We turn next to the question of how an organization determines its pay level—the amount of overall pay that employees earn in that organization relative to what employees earn in other organizations. As with motivational strategies, the pay-level strategy an organization chooses depends largely on its competitive strategy. However, the first step in the process of determining pay level is to gain information to understand the compensation packages being provided by other organizations. This is done through pay surveys.

Pay level

The compensation decision concerning how much to pay employees relative to what they could earn doing the same job elsewhere.

PAY SURVEYS

To determine the appropriate pay level, an organization must identify a comparison group and then obtain data about compensation in the organizations that make up the comparison group. The result of this analysis is a pay survey that provides information about how much other organizations are paying employees. Pay surveys are often conducted by consulting firms, which obtain confidential information from numerous organizations and create reports that describe average pay levels without divulging information about specific companies. Professional organizations, such as associations of accountants and engineers, also conduct pay surveys that report wage and salary information for particular positions.

Pay survey

Gathering information to learn how much employees are being paid by other organizations.

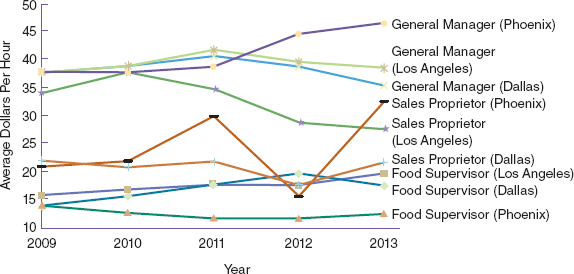

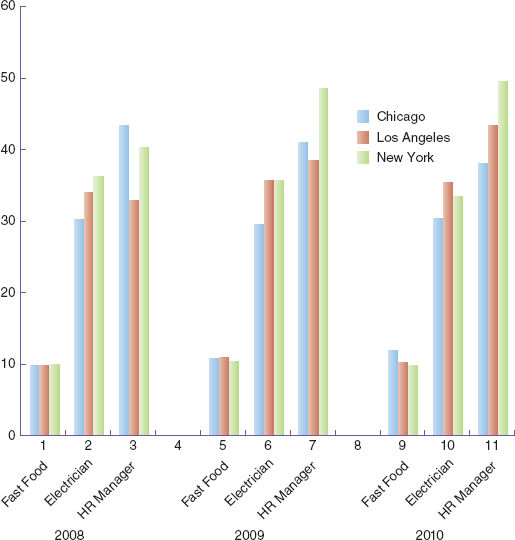

A source of public data about pay level is the Bureau of Labor Statistics, an agency of the U.S. Department of Labor, which collects employment data.49 For instance, Figure 11.4 shows compensation rates reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for three different jobs in three different cities. The data show that in each city, electricians are paid more than fast food workers. Fast food workers were generally paid the same in all three cities during the first two years, but in 2010 they received higher pay in Chicago. Over the three-year period, compensation for human resource managers increased in Los Angeles and New York but decreased in Chicago. This information can be helpful for organizations trying to determine how much to pay employees. However, thinking carefully about the information in Figure 11.4 reveals a number of potential problems with pay surveys.

Figure 11.4 Sample BLS Pay Survey Results. Source: Information from Bureau of Labor Statistics (http://www.bls.gov/home.htm).

One problem is choosing the appropriate comparison group. An interesting example is how a major university might conduct a pay survey to determine how much to pay athletic coaches. One potential choice is to use all university coaches as the comparison group. Another choice is to use coaches in the top 20 nationally ranked programs. Since high-performing college coaches often receive offers from professional teams, still another choice may be a comparison group that includes coaches of professional teams. The outcome of a pay survey will likely be very different depending on which of these groups is chosen.

How does an organization choose the right comparison group? Good comparison groups often include organizations that compete in the same product and service markets.50 As shown by the data in Figure 11.4, choosing the right geographic region for the comparison can also be important. A firm using comparison data from Los Angeles might determine that it is paying human resource managers an above-average wage, but the same firm might determine that it has below-average pay if it uses comparison data from New York. Of course, the correct comparison group depends on the nature of the position. Some jobs, such as bank teller, tend to draw workers from a rather small geographic area, suggesting that the best comparison group is probably the local city. Other jobs, such as investment banker, tend to draw workers from much larger geographic areas, meaning that the best comparison group may be a multistate area or even the entire nation. The correct comparison group can also depend on competitive strategy. A company in New York may not see all companies, even those in the same industry, as its competitors. The company may want to compare its salaries only with salaries at the most service-oriented competitors. Such a comparison requires data that may be available only from a consulting firm.

As illustrated in the “Technology in HR” feature, the Internet creates easy access to data, but not all data are good data. One potential problem with pay surveys concerns the difficulty of obtaining salary information for specific jobs. Identifying jobs that are the same in all organizations may seem relatively simple, but it is actually quite difficult. For example, a secretary in one organization may have a large number of important duties such as planning and maintaining budgets. A secretary in another organization may act primarily as a receptionist who answers telephone calls. In Figure 11.4, the position of human resource manager is the one most likely to suffer from this problem. The duties and responsibilities of managers in one organization may be very different from those of managers in other organizations. Factors that make the human resource manager position different across organizations include the number of people being supervised, the nature of the work assigned, and the education and training of subordinates. To address this problem, high-quality pay surveys obtain information that extends beyond job titles and includes a list of actual duties performed.

Because of the difficulty in creating pay comparisons for every job, a common practice in pay surveys is to obtain comparison data only for key positions. Comparing pay level in these key positions helps the organization picture its overall compensation relative to other organizations. The amount of pay for positions not included in the comparison data is then determined by weighing their value relative to the positions included in the survey.

The data in Figure 11.4 also illustrate that pay levels change over time—and they may change rapidly. For example, notice the rapid upward trend of pay for human resource managers in Los Angeles. An organization in Los Angeles using old comparison data might conclude that it is paying more than competitors when it is actually paying only average. Good pay surveys thus use current data.51

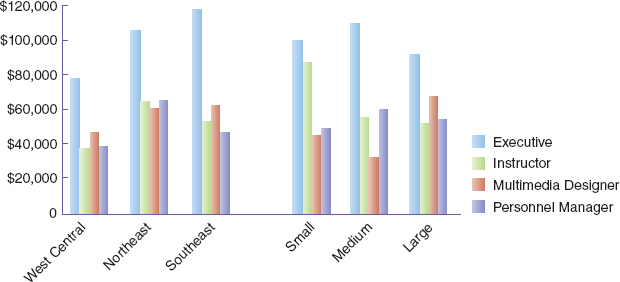

It should be clear by now that when it comes to pay surveys, an organization must clearly understand the data it is obtaining from a comparison group in order to know whether it is making an appropriate comparison. Consider one final example. Figure 11.5 illustrates the results of a pay survey for employees who work in the field of training and development.52 Suppose a small organization located in Colorado pays an executive in that field an annual salary of $90,000. If the organization compares this salary with salaries within its geographic area, then it will conclude that it is paying an above-average wage. However, if it uses small firms for the comparison, it will conclude that it is paying a below-average wage. Of course, a solution is to obtain data from small firms in Colorado. This is, however, somewhat difficult in practice, because the number of organizations fitting such a specific category and willing to provide data may not be large enough to make up a good comparison sample. The organization may need to use a number of different comparison groups and combine the results to arrive at the estimate that best reflects its standing relative to others. No matter the specific approach, it is critical that organizational leaders critically evaluate the usefulness of the data.

Figure 11.5 Pay Survey Results for Training Professionals. Source: Information from Holly Dolezalek, “The 2005 Annual Salary Survey,” Training 42, no. 10 (2005): 12–23.

PAY-LEVEL STRATEGIES

After obtaining information about compensation in other organizations, the next step is to develop a pay strategy that determines how high pay should be. One possible compensation strategy is to pay employees more than what they can earn elsewhere. For instance, our earlier discussion of Marriott explained how the hotel chain strives to maintain a higher level of pay than other employers. But not all organizations benefit from paying more than their competitors. There are three basic strategies for pay level: meet-the-market, lag-the-market, and lead-the-market.53 Here “the market” refers to a selected group of organizations, such as organizations in the same industry or in the same geographical area. Data about the pay of these comparative organizations is collected through the pay survey.

- An organization with a meet-the-market strategy establishes pay that is in the middle of the pay range for the selected group of organizations. Some employees in the organization may be paid more than they could earn elsewhere, and some may be paid less. On average, though, the pay level is the same as the average pay level for employees across the comparison group. An organization that adopts a meet-the-market strategy seeks to attract and retain quality employees but does not necessarily use compensation as a tool for maintaining a superior workforce.

Meet-the-market strategy

A compensation decision to pay employees an amount similar to what they can make working for other organizations.

- With a lag-the-market strategy, an organization establishes a pay level that is lower than the average in the comparison group. Of course, some employees may be paid more than similar employees working for other organizations. But the average level of pay for the entire organization is lower than the average level of pay for organizations in the comparison group. In most cases, organizations adopt a lag-the-market pay level strategy as part of a broader strategy to reduce labor costs.

Lag-the-market strategy

A compensation decision to pay employees an amount below what they might earn working for another organization.

- In an organization with a lead-the-market strategy, the average pay level is higher than the average in the comparison group. Once again, this doesn't mean that every employee will receive higher wages. However, a lead-the-market strategy suggests that the organization seeks to pay most employees more than they would be able to earn in a similar position in another organization. The labor cost for each employee may be higher in these organizations, but they expect the higher cost to be offset by higher performance and lower turnover. The Container Store, which is profiled in the “Building Strength Through HR” feature, is one example of an organization that benefits from a lead-the-market strategy.

Lead-the-market strategy

A compensation decision to pay employees an amount above what they might earn working for another organization.

LINKING COMPENSATION LEVEL AND STRATEGY

Even though wages rise as compensation level increases, profitability can often be increased by better employee performance. Differences in pay level can therefore be linked to strategic decisions. Organizations with Bargain Laborer HR strategies tend to focus on reducing labor costs. These firms most frequently adopt lag-the-market or meet-the market strategies. At the other extreme, organizations with Free Agent HR strategies use compensation to attract top performers. These firms tend to pursue lead-the-market strategies that help them to hire high-quality workers who are highly skilled. Organizations with internal labor strategies emphasize the development of long-term relationships rather than focusing on money. These organizations generally adopt pay levels somewhere between meet-the-market and lead-the-market. Organizations pursuing a Committed Expert HR strategy tend to have more of a lead-the-market orientation than those pursuing a Loyal Soldier HR strategy.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4

How Is Compensation Structure Determined?

When you graduate from college and accept a full-time position, do you expect to get paid the same as everyone else who works for the company? The likely answer is no. You might expect to earn less than someone who has been in the same position for several years. However, you might expect to earn more than an employee without a college degree. You might also expect to make more (or less) than a friend who works in a different department and has a degree in a different field. These differences in pay relate to the organization's pay structure. Whereas pay level is concerned with how compensation differs across organizations, pay structure focuses on how compensation differs for people working in the same organization.

There are two major methods for determining pay structure. One method—often referred to as job-based pay—focuses on evaluating differences in the tasks and duties associated with various positions that employees have. With this method, it is expected that people who have more difficult jobs will be paid more. The other method focuses on directly evaluating differences in the skills and abilities of employees and is often called skill-based pay. In an organization using skill-based pay, an employee might be paid for having a certain set of skills, even if the tasks that the employee normally performs do not require those skills.

Job-based pay

A determination of how much to pay an employee that is based on assessments about the duties performed.

Skill-based pay

A determination of how much to pay an employee that is based on skills, even if those skills are not currently used to perform duties.

JOB-BASED PAY

A job-based pay approach typically uses a point system that assigns a numerical value to each job position. The numerical value is designed to capture the overall contribution of the job to the organization. Of course, not everyone performing a certain job will be paid the same amount. Each job is assigned a range of acceptable compensation. Individuals in the job who contribute less are paid near the bottom of the range, and those contributing more are paid near the top. The general trend, however, is for people in jobs worth more points to receive higher compensation.

Point system

A process of assigning numerical values to each job in order to compare the value of contributions within and across organizations.

A simplified example including management accountants is shown in Figure 11.6.54 These jobs differ on the dimension of accountability and are ordered so that those with lower accountability appear on the left side of the graph. Moving from left to right, we move to jobs with higher accountability and thus higher point values. The box above each point category represents the range of pay associated with that category. For example, the midpoint of the range for people working in low-accountability positions is $83,000. The bottom of the range is $73,000, and the top of the range is $93,000.

One widely used point system is the Hay System.55 This system was developed and is marketed by the Hay Group, a worldwide compensation consulting firm. The Hay System evaluates jobs in terms of four characteristics: know-how, problem solving, accountability, and working conditions.56

- Know-how concerns the knowledge and skills required for the job. Jobs are given more points when they require an employee to know and use specialized techniques, when they involve a need to coordinate diverse activities, and when they involve extensive interpersonal interaction.

- Problem solving assesses the extent to which the job requires employees to identify and resolve problems. Higher points are assigned to jobs that are less routine, require more thought, and frequently call for adaptation and learning.

- Accountability focuses on how much freedom and responsibility a job affords. Jobs are given higher ratings when the people filling them have substantial freedom to determine how to do things and when the tasks performed have a large impact on the organization's results.

- Working conditions captures the extent to which performing the job is unpleasant. The main idea is that jobs should pay more when they require employees to work in dirty, strenuous, or dangerous conditions.

Figure 11.6 Job-Based Pay for Management Accountants. Source: Some of the data for these ranges are from Karl E. Reichardt and David L. Schroeder, “2005 Salary Survey,” Strategic Finance 87, no. 12 (2006): 34–50.

The points assigned on each of the four dimensions are added together to create a numerical score that represents the value of the job. Jobs are then arranged along a continuum from positions assigned low point values to positions assigned high point values. Each job within the organization is given a specific point value. Jobs with similar point values are then grouped together into categories. A category that includes jobs within a specific range is known as a pay grade. A midpoint value, which represents a target for average pay of the jobs included in the category, is established for each pay grade. A range is then created around each midpoint so that pay for everyone performing jobs worth a certain number of points falls within the range. An individual's level of compensation within the range is determined by things such as experience and performance level.

An important consideration for job-based pay concerns the range of point totals that are grouped together into a pay grade. Some organizations adopt narrow categories so that each pay grade includes only a few jobs. This process allows clear distinctions among positions. Other organizations use a process known as broadbanding. Here, there are fewer categories, and each category includes a broader range of jobs. The practice of broadbanding thus results in fewer pay grades, which are sometimes referred to as pay bands. An organization that uses broadbanding may need to establish and track only three to five pay grades, resulting in improved efficiency. At the same time, each pay grade includes more jobs covering a wider range of points. Thus, the pay range within each pay grade is larger, so that an employee's salary does not hit the top of the range as quickly. Indeed, more flexibility in determining an individual's pay is a primary benefit of broadbanding.

Broadbanding

The practice of reducing the number of pay categories so that each pay grade contains a large set of different jobs.

Job-based pay systems have a number of advantages. Use of the point system provides a clear method for controlling and administering pay. Centralized human resource personnel conduct surveys and establish guidelines for determining how much to pay each employee. Pay practices that are job-based also appear to be very objective. Employees can directly compare their pay with the pay of others in the organization, strengthening perceptions of internal equity. Moreover, assigning numerical values to specific factors that are summed into an overall score is thought to reduce bias. Having a numerical value for each job also makes it easier to compare vastly different jobs. Very different positions, such as nurse and marketing coordinator, can be assigned points and compared to get a sense of pay equity.57

Job-based pay systems also have disadvantages. One potential problem is centralized control. As explained in our earlier discussion of the Marriott Corporation, pay can often be more effectively controlled by local managers, who have a better sense of employee qualifications and alternative work opportunities. Another disadvantage is the fact that in many job-based systems, employees at the top of a pay range can only receive higher compensation if they are promoted into a position worth more points. This often has the effect of encouraging individuals to seek promotions even when their interests and skills don't match the requirements of the higher-level position. This emphasis on promotions is one reason organizations have begun broadbanding so that employees can move up within a large band without being promoted to a different job. Another concern with job-based pay is that individuals often try to get their current positions reevaluated and valued with higher points, so that they will receive higher pay, even though the tasks they are performing have not really changed. Inflexibility and resistance to change are also common with job-based pay systems, since the major focus is on classifying tasks into clear-cut objective categories that can be represented by a numerical score. Job-based compensation makes it difficult to hire new employees who require a wage that is above the established range. Finally, there is little incentive for employees to learn new skills that are not part of their formal job duties.

SKILL-BASED PAY

A skill-based pay system shifts emphasis away from jobs and focuses on the skills that workers possess. In essence, this system pays people relative to their long-term value rather than relative to the value of their current position. Employees are paid more when they develop more skills. The primary objective is to encourage the development of skills linked to the overall strategic direction of the organization.

An application of skill-based pay in a manufacturing plant is shown in Figure 11.7. In this case, Skill Set 1 might include the ability to solve simple math problems, communicate orally, and read and follow written directions. People need this skill set in order to be hired at the starting rate of $11 per hour. Once employees learn Skill Set 2 (operating basic machines and equipment), their pay rises to $15 per hour. Pay increases to $18 per hour when employees learn Skill Set 3 (production planning, equipment repair) and to $21 when they learn Skill Set 4 (ability to interact with vendors and customers). Employees are thus paid for the skills they develop rather than for occupying a specific position.

Skill sets can be defined in a number of ways. Some organizations require employees to learn entirely new skills, as when a salesperson learns accounting skills. Other organizations encourage employees to develop deeper skills in specific areas, as when an accountant learns new tax rules and regulations. In either case, the primary objective is to tie pay increases to the development of skills useful to the organization.

Several different methods can be used to determine whether an employee has learned a skill set. In some cases, written tests are used to assess learning. In other cases, coworkers or supervisors administer tests or observe actions to certify that a skill set has been mastered. Regardless of how the assessment is made, an important feature of most skill-based pay systems is allowing employees to learn new skills at their own pace. Some employees advance quickly under this plan, while a few never advance to higher levels.

Figure 11.7 Skill-Based Pay.

Skill-based pay plans do have some disadvantages. One problem is that payroll costs tend to be higher with skill-based pay. Employees are paid higher wages when they acquire additional skills, even if they don't use those skills to perform their current duties. Training costs can also be high if classes and other training resources are needed to develop the skills. In addition, problems arise when employees master the highest skill set and perceive that they have no more room for advancement.58

Even with the potential disadvantages, skill-based pay appears to offer a number of benefits. For one thing, the increased emphasis on skill development provides a better-trained workforce. A related advantage is greater flexibility in production processes. In most cases, a large number of employees have been trained to perform several different duties. Thus, when someone is ill, or when someone quits, several substitutes are available to fill in. Emphasizing skills rather than jobs also helps to build a culture that supports greater participation and employee self-management.59 These benefits are substantial enough that skill-based pay has been linked to higher organizational productivity.60

LINKING COMPENSATION STRUCTURE TO STRATEGY

Once again, we can link organizations' compensation structure to their overall HR strategies. In organizations pursuing Free Agent HR strategies through variable transactional compensation, pay is used to attract people with specific skills. Skill-based pay that compensates individuals for the specific skills they bring is thus useful for many organizations pursuing this strategy. Internal equity is not critical, and people with better skills are paid substantially more than people with limited skills. Once people are hired in these organizations, little emphasis is placed on the acquisition of new skills, since employees are not expected to stay with the organization for long.

Skill-based pay can also be beneficial for organizations pursuing a Loyal Soldier HR strategy. Organizations pursuing this strategy use uniform relational compensation to bind individuals to the organization and minimize differences between employees. Skill-based pay that is linked to specific training is helpful in promoting these goals. Giving everyone the opportunity to learn new skills and advance to higher pay levels builds a sense of teamwork. Linking pay to the skills needed by the organization also forms stronger ties between employees and the organization, which creates uniformity.

Job-based pay is most closely aligned with the Committed Expert HR strategy and variable relational compensation. The emphasis on long-term employment relationships makes internal equity particularly important in these organizations, and opportunity for promotion is a significant motivator. With job-based pay, employees are able to see a rational basis for pay decisions. They are also able to see how promotions can increase their pay. Compensation is based on length of time with the organization and type of input contributed, but a sense of equity is retained.

Job-based pay is also beneficial for organizations with Bargain Laborer HR strategies. These organizations don't usually seek to hire people who have developed specific skills. The overall objective is to minimize labor cost by paying people only for the contributions they provide and not for skills in other areas.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 5

How Do Government Regulations Influence Compensation?

We end the chapter with a look at how government regulations affect the decisions organizations make about compensation. First, we describe a major federal law in this area, and then we discuss state and local regulations. Taken together, these laws create some important requirements with which organizations must be familiar.

FAIR LABOR STANDARDS ACT

Have you ever heard people say they don't earn overtime because their jobs are “exempt”? What does it mean to be exempt? Perhaps you have heard statements about how pay in certain jobs compares with the minimum wage. Who decides what the minimum wage is? Both of these questions are related to the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), a federal law that governs many compensation practices. The FLSA, which was passed in 1938, is designed to protect employees. The law establishes a national minimum wage, regulates overtime, requires equal pay for men and women, and establishes guidelines for employing children. Many types of workers, however, are exempt from FLSA regulations.

Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

Federal legislation that governs compensation practices and helps ensure fair treatment of employees.

Exempt and Nonexempt Employees

The FLSA creates two broad categories of workers: exempt and nonexempt. Exempt employees are not covered by FLSA regulations. Members of the other group, often referred to as nonexempt employees, are covered. Perhaps the most noticeable difference between these groups is how they are paid. Exempt employees can be paid a salary. In most cases, they aren't required to keep track of the actual hours they work. Nonexempt employees are paid an hourly wage. For these employees, the number of hours worked, including the beginning and ending times, must be carefully recorded. This basic difference stems from FLSA regulations. Employees who are covered by the FLSA are required to keep track of their hours and be paid on an hourly basis, whereas employees who are not covered can be paid a set amount that is not directly tied to hours worked.

Exempt employees

Workers, such as executives, administrators, professionals, and sales representatives, who are not covered by the FLSA.

Nonexempt employees

All employees who are not explicitly exempt from the FLSA, sometimes referred to as hourly workers.

What determines whether an employee is exempt or nonexempt? As a starting point in understanding these classifications, it is easiest to think of all employees as being covered by the FLSA and then identify which types of workers are exempt. The list of specific types of exempt workers is quite lengthy and includes specific types of laborers, such as amusement park employees and farm workers. There are, however, four general classifications that usually underlie the exempt designation.61

- The executive exemption applies to workers whose primary duties are managing a business and supervising others.

- The administrative exemption applies to workers who perform office or nonmanual work that is directly related to management. They must exercise substantial discretion and judgment in their work.

- The professional exemption applies to employees who perform tasks that require special skills and advanced knowledge learned through specialized study.

- Workers may also be exempt from the FLSA through the outside sales exemption, which applies to salespeople who work away from the place of business.

In any of these cases, the employees must spend at least 80 percent of their workday doing work activities that qualify them for the exemption. For instance, to qualify for the outside sales exemption, the salesperson must spend at least 80 percent of his or her time selling in locations other than the company premises. Table 11.2 provides a brief summary of the four major exemptions.