How Can Strategic Employee Retention and Separation Make an Organization Effective?

Employees are a primary asset of almost every organization, but identifying, hiring, and training good employees can be costly. Replacing an employee who quits costs an organization between one and two times the annual salary of the position.1 This means, for example, that replacing an accountant with an annual salary of $75,000 costs the firm between $75,000 and $150,000. The company loses money not only from the costs associated with hiring a replacement but also from lower productivity and decreased customer satisfaction.2 Such costs were illustrated by a study which found that Burger King restaurants with higher employee turnover have longer wait times that translate into decreased customer satisfaction.3 Employee turnover, then, is very expensive, harms customer service, and relates negatively to organizational performance.4 Good employees leaving to work for competitors can also be a problem in that it increases the effectiveness of a rival.5 The expense and negative consequences of replacing workers requires most organizations to focus effort on employee retention, a set of actions designed to keep good employees once they have been hired.

Employee retention

The act of keeping employees; retaining good workers is particularly important.

Whereas retaining good employees is beneficial, organizations lose money when they retain poor employees. Ensuring that nonproductive employees don't continue with the organization is often just as important as retaining productive workers. Furthermore, changes in economic conditions and product demand sometimes force organizations to reduce the size of their workforce. Employee separation is the process of efficiently and fairly terminating workers.

Employee separation

The act of terminating the employment of workers.

SAS Institute, Inc., is a successful organization that benefits from concerted efforts to retain productive workers. CEO Jim Goodnight summarizes his views about employee retention when he says, “My chief assets drive out the gate every day. My job is to make sure they come back.”6

SAS is the world's largest privately owned software company, with revenues exceeding $2.7 billion each year. Organizations such as American Express, Chrysler, Pfizer, and the U.S. Department of Defense use SAS products to help them gather and analyze large amounts of information. Many college students also use SAS products to conduct statistical analyses for class projects.7

An important key to success for SAS is high customer satisfaction: Its customer retention rate is above 98 percent. One reason for this success is a relentless drive to create innovative products. SAS reinvests 30 percent of its revenue in research and development each year. Another reason for success is its emphasis on building long-term relationships with clients. Each year, the company conducts a survey to determine how well customer needs are being met. Rather than spend money on marketing and advertising, SAS spends money satisfying customer needs.

Having a stable workforce made up of highly intelligent knowledge workers is critical for providing outstanding customer service.8 Jim Goodnight sums up the human resource philosophy he has practiced over the years by stating, “I think our history has shown that taking care of employees has made the difference in how employees take care of our customers.”9 The average tenure at SAS is 10 years, and 300 employees have worked there for at least 25 years, which is unusual in the software industry. SAS develops long-term relationships with employees, who in turn build long-term relationships with customers. Employees treat customers with the same respect and care that they receive from SAS.10

A good indication of successful human resource practices is the low percentage of employees who leave SAS each year. The annual turnover rate at SAS has never been higher than 5 percent, a rate that is much lower than that at competing software firms. The lower turnover saves SAS up to $80 million each year.11

What does SAS do to keep employee turnover so low? One answer is that it has created a great work environment. The great environment was recognized by Fortune magazine, which has included SAS among the top three places to work for the past four years. Its work sites, located in beautiful areas where people want to live, have a campus atmosphere.12 SAS employs a resident artist who coordinates sculptures and art decorations.13 In addition, all professional workers have private offices.14 Yet, perhaps the most important aspect of the work environment is the expectation that employees leave the office between 5 and 6 o'clock each evening. The corporate philosophy is that working too many hours in a day leads to decreased productivity for creative workers. Employees are encouraged to spend dinnertime at home with their families.15

Another reason SAS excels at employee retention is its exceptional benefits. Back in its startup days, SAS faced the possibility of losing some key personnel who were going on maternity leave and unlikely to return to work. Goodnight and other leaders solved the problem by creating an onsite daycare center. In the ensuing 25 years, SAS has become a leader in offering family-friendly benefits. Employees are often seen in the cafeteria eating lunch with their young children who attend onsite daycare. Vacation and sick leave policies are generous, and most workers have the option of flexible scheduling.16 The company also has excellent fitness facilities, which even launder gym clothes.17 Pay is rarely more than what is offered by other software firms, but SAS does offer competitive compensation packages that include profit sharing.

SAS is also good at identifying and retaining employees who are compatible with its organizational culture. People who fit with the family-friendly environment are recruited across industries and not just from the software sector. Not being located in Silicon Valley helps SAS recruit workers who are less likely to move to other companies. SAS also takes advantage of poor economic conditions by hiring the best workers who have been laid off from competitors.18 For each open position, the company receives up to 200 applications.19 To retain good employees who want to pursue different jobs, the company works hard to facilitate internal transfers.20 Those who are hired but don't fit the organizational culture are encouraged to leave SAS and find other employment.21

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

How Are Employee Retention and Separation Strategic?

The SAS Institute example shows how an organization can benefit from placing a strong emphasis on retaining workers. As we have seen with other human resource practices, however, such a strong emphasis on retaining workers may not be as beneficial for other organizations. Strategies for retaining employees are most effective when they fit with an organization's strategy. Figure 7.1 illustrates how employee retention and separation fit with competitive business strategy and overall HR strategy.

STRATEGIC EMPHASIS ON EMPLOYEE RETENTION

Retaining good employees is the very essence of an internal labor orientation. The competitive advantage here comes from developing a loyal workforce that consistently excels at satisfying customer demands. For organizations that use the Loyal Soldier HR strategy, retaining employees reduces recruiting expenses and provides workers with a sense of security that persuades them to work for slightly lower wages than they might be able to earn at competing firms. For instance, people employed at a state government office might be able to earn more money elsewhere but prefer to continue working as public servants because government agencies are less likely to replace workers.

Figure 7.1 Strategic Retention and Separation of Employees.

With the Committed Expert HR strategy, employee retention helps build a workforce with unique skills that employees of other organizations do not have. These skills are critical for producing exceptional products and services that cannot be easily duplicated by competitors. SAS Institute uses a Committed Expert strategy of this kind. Employees with specialized skills develop long-term relationships with customers, who continue to purchase SAS products because of the excellent service they receive.

Employee retention is not as critical for organizations with an external labor orientation. Employees are expected to leave the organization to pursue other opportunities. For organizations pursuing a Bargain Laborer HR strategy, separations are seen as a necessary consequence of combining entry-level work with relatively low wages. Indeed, a moderate amount of employee turnover has been found to be beneficial with the Bargain Laborer HR strategy.22 For organizations with a Free Agent HR strategy, some employee turnover is desirable, since those who leave can often be replaced by individuals with more up-to-date knowledge and skills.

STRATEGIC EMPHASIS ON EMPLOYEE SEPARATION

When it comes to pursuing a differentiation strategy, employee separation can be just as important as employee retention. Innovative organizations rely on highly skilled employees who have specialized knowledge and ability. An employee who is not capable of providing skilled inputs does not contribute, making termination of nonperforming employees critical for organizations that seek to produce premium goods and services.

Organizations pursuing a Committed Expert HR strategy focus on terminating the employment of low performers soon after they are hired. Quickly identifying individuals who do not fit the organizational culture, or who appear unable to develop needed skill and motivation, reduces the cost of bad hiring decisions. A law firm engages in such practice when it denies promotion to a junior-level attorney who is not performing at the level necessary for making partner.

Organizations with a Free Agent HR strategy benefit from frequently replacing employees with others who bring new skills and a fresh perspective. Employee separation is a common occurrence in such organizations, and ongoing efforts are needed to ensure that disruptions from frequent turnover are minimized as much as possible.23 For example, an organization might create incentives that encourage employees working on a major project not to leave until the project is completed.

Managing employee separation is not as critical, but still important, for organizations that have cost-reduction strategies. For example, an organization pursuing a Loyal Soldier HR strategy has the primary goal of hiring young employees who stay with the organization for long careers. Having high performers is not as critical in these cost-focused organizations, which means that termination of employment is only necessary when a worker clearly fails to meet minimum expectations. People who are not performing well in a specific job are frequently transferred to other positions. The overall focus on stability also makes employee layoffs an uncommon occurrence. Organizations with Loyal Soldier HR strategies thus expend little effort on developing employee separation practices.

Similarly, effective management of employee separation is not critical for an organization with a Bargain Laborer HR strategy. Because of their relatively low wage rates and repetitive jobs, such organizations expect many of their employees to move on. Furthermore, the basic nature of the work and the emphasis on close supervision mean that identifying and terminating low performers need not be a major focus. A good example is fast-food restaurants that rarely have policies to actively identify and terminate low-performing workers. Employees are allowed to continue working as long as their performance meets minimum standards.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

How Can Undesirable Employee Turnover Be Reduced?

Who is most likely to remain with an organization? As shown in Figure 7.2, the answer is that employees with average performance are most likely to remain with an organization. High performers are at risk of being recruited away by other organizations to work in more-fulfilling and better-paying jobs. Low performers likely perceive lack of fit with their current position and resent the relatively low compensation they receive. Interestingly, this effect for low performers has been shown to occur predominantly when organizations are located in countries such as the United States that value high individual achievement and greater separation between people of varying status.24

Of course, organizations are most concerned about losing high performers. From the organization's perspective, losing low performers is of little concern and is usually seen as a desirable outcome. From the employee's point of view, much of the effect of leaving depends on whether we're dealing with voluntary turnover, in which the employee makes the decision to leave, or involuntary turnover, in which the organization terminates the employment relationship. Not surprisingly, involuntary turnover has a much more negative effect on the employee.

Voluntary turnover

Employee separation that occurs because the employee chooses to leave.

Involuntary turnover

Employee separation that occurs because the employer chooses to terminate the employment relationship.

One way of thinking about turnover is thus to categorize it along two dimensions. One dimension is whether the person leaving is a high or low performer. The second dimension is whether the person plans to voluntarily leave. Combining the two dimensions results in four possible types of turnover:25

- Functional retention, which occurs when high-performing employees remain employed, can benefit both the individual and the organization.

- Functional turnover, which occurs when low-performing employees voluntarily quit, can also benefit both parties.

- Dysfunctional retention occurs when low-performing employees remain with the organization. Later in the chapter, we deal with situations in which the organization must terminate low performers who do not leave voluntarily.

- Dysfunctional turnover occurs when an employee whose performance is at least adequate voluntarily quits. We focus on this situation in the remainder of this section.

Dysfunctional turnover

Undesirable employee turnover that occurs when good employees quit.

When a good employee chooses to leave, the organization usually must identify and hire another worker to fill the position. This process can be highly disruptive. Just think of a product development team with high turnover among members. Frequent personnel changes make it difficult for the team to coordinate efforts. A lot of time and energy are spent on finding new team members and teaching them the necessary skills. All this energy and time is wasted if people leave just as they are becoming integrated into the team. Frequently replacing employees consumes many resources and makes it difficult for organizations to develop a competitive advantage. In general, organizations are thus more effective when they have programs and practices that proactively work to reduce employee turnover.

Figure 7.2 Relationship Between Employee Performance and Turn. Source: Based on information from Michael C. Sturman, Lian Shao, and Jan H. Katz, “The Effect of Culture on the Curvilinear Relationship Between Performance and Turnover,” Journal of Applied Psychology 97 (2012): 46–62.

RECOGNIZING PATHS TO VOLUNTARY TURNOVER

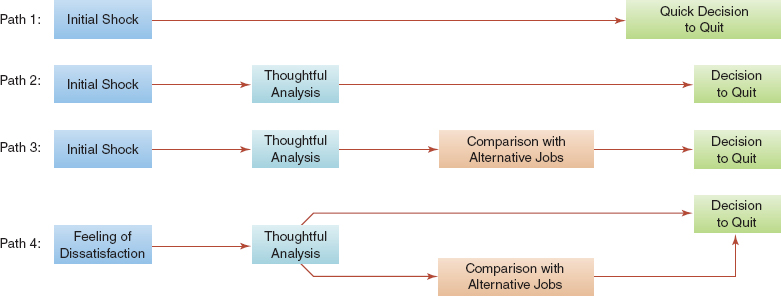

We've seen that dysfunctional turnover causes problems for organizations. What, then, can they do to prevent or reduce it? A starting point is to understand why employees choose to leave.26 Observations of actual decisions suggest specific processes explain how turnover unfolds over time.27 One difference is the amount of thought that goes into the decision. Since moving from one organization to another is a radical life change for most people, we might expect a person to put a great deal of thought into a decision to move. Yet sometimes people make hasty decisions without carefully thinking about the consequences. Another difference concerns whether a single event can be identified as the beginning of the decision to leave an organization. Figure 7.3 uses these differences to capture four paths to quitting. Next, we examine each of the four paths in more detail.

Figure 7.3 Paths to Decisions to Quit. Source: Information taken from Thomas W. Lee and Terence R. Mitchell, “An Alternative Approach: The Unfolding Model of Voluntary Employee Turnover,” Academy of Management Review 19 (1994); 51–90.

Quick Decision to Leave

The first path shown in Figure 7.3 is a quick decision to leave the organization. This path begins with some external event that causes an employee to rethink the employment relationship. The employee might be asked to engage in unethical behavior, for example, or might be denied a promotion. The event may not even be directly related to work. For instance, the employee might become pregnant or receive an inheritance. Regardless of what the event is, the result is a highly emotional reaction that leads the employee to quit without much thought.

Calculated Decision to Leave

Like the first path, the second path shown in the figure begins with an event that causes an individual to begin thinking about leaving the organization. Here, however, the individual does not make a quick decision. Alternatives are weighed, and the benefits of staying are compared with the benefits of leaving. For instance, an employee may learn that others in the organization are making more money even though they have less experience on the job. The employee who hears this news might carefully analyze the benefits and drawbacks associated with staying with the present employer. As explained in the “Building Strength Through HR” feature, companies can intervene at this point to communicate potential benefits of staying. Such effort is helpful because a decision to leave the organization occurs only after careful thought. Note, however, that the decision for this path is not influenced by alternative job opportunities. The decision is simply whether to stay or leave.

Comparison with Other Alternatives

The third path in the figure involves a comparison between the current job and other alternatives. Once again, some external event initiates thoughts about leaving the organization. For example, research has established that receiving a job offer from a different company is a critical event that often leads an employee to quit.28 Once the event has occurred, the employee begins to look at alternative opportunities. The benefits of jobs with other organizations are carefully compared with the benefits of the current job. A decision to leave becomes a conscious choice between the present job and specific alternatives. This path appears to be the most common course that leads an employee to leave an organization.

Sense of Dissatisfaction

In the final path shown in Figure 7.3, the employee develops a general sense of dissatisfaction over time. This sense of dissatisfaction leads to either a calculated decision to leave or a search and comparison with other job opportunities. This path is different from the other paths in that no specific event can be identified as causing the employee to begin thinking about quitting.

UNDERSTANDING DECISIONS TO QUIT

An important part of each path to turnover is a lack of satisfaction with the current work situation. It is easy to see how a lack of satisfaction can lead to a decision to leave. Most of us can recall a time when we have been part of a team, club, or other organization that we wanted to leave as fast as possible. Perhaps it was a sports team where teammates fought among themselves and seldom won games. Maybe it was a student work team that included several individuals who didn't do their share of the work. Being stuck in such a team can have a negative impact on personal happiness. Working in an organization with an undesirable environment can also lead to feelings of dissatisfaction. Employees who are more dissatisfied are more likely to quit than are employees who experience a positive work environment.29 In particular, environments that are plagued by constraints, hassles, dysfunctional politics, and uncertainty about what to do increase the likelihood that employees will be less satisfied and quit.30

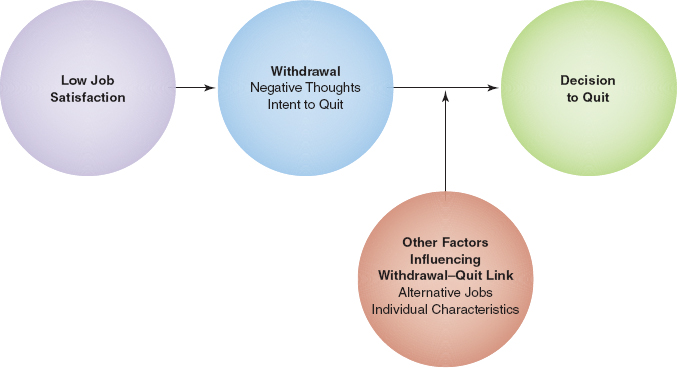

A basic model illustrating how lack of satisfaction leads to quitting is shown in Figure 7.4. The employee's decision to leave begins with a sense of low job satisfaction. Consistent with the paths described above, this sense may be created by a specific event or as part of a global feeling that builds over time. Individuals who are not satisfied with their work arrangements begin to withdraw from the organization and think about quitting. Thoughts translate into action as individuals begin searching for alternative employment, which often leads to turnover.31 Other factors—such as the availability of other jobs and individual personality characteristics—also influence whether thoughts of withdrawal are acted upon so that an individual actually leaves. Let's explore each aspect of the model in order to better understand why people quit jobs.

Low Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction represents a person's emotional feelings about his or her work. When work is consistent with employees' values and needs, job satisfaction is likely to be high.32 Satisfaction increases when employees are able to pursue goals and activities that are truly important to them.33 Employees are also happier when they are able to do work that fits with their interests and life plans.34 For example, a high school mathematics teacher is likely to experience high job satisfaction when she perceives that she is helping others develop critical life skills.

Job satisfaction

Employees' feelings and beliefs about the quality of their jobs.

Figure 7.4 How Job Satisfaction Leads to Quitting. Source: Adapted from Peter W. Hom, Fanny Caranikas-Walker, Gregory E. Prussia, and Rodger W. Griffeth, “A Meta-Analytical Structural Equations Analysis of a Model of Employee Turnover,” Journal of Applied Psychology 77 (1992): 905. Adapted with permission.

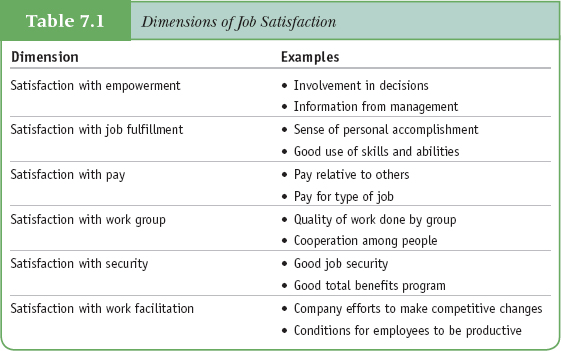

Employees often make an overall assessment of their job satisfaction, but job satisfaction can also be divided into different dimensions, as shown in Table 7.1.35 An employee who is satisfied with one aspect of the job may not be satisfied with others. Someone may have high satisfaction in the area of job fulfillment because he enjoys the work he does, for instance, but have little satisfaction with how much pay he receives. Also, not every aspect of job satisfaction is equally important to every employee. Some people value empowerment more than security, whereas others will place greater value on security.36 These different values and perceptions mean that job satisfaction represents a complicated mix of feelings. Nevertheless, satisfaction with compensation is often the dimension that is most strongly related to overall perceptions of job satisfaction.

Overall job satisfaction varies among organizations as well as among individuals. On average, some organizations have happier employees. Those with happier employees tend to be more productive.37 Yet even organizations with high overall levels of job satisfaction likely have individual employees who are not happy with their jobs.

Withdrawal from the Organization

Employees who are unhappy with their work tend to withdraw from the organization. Withdrawal occurs when employees put less effort into their work activities and become less committed to the organization. As their sense of attachment to the organization decreases, they feel less obligated to work toward ensuring the organization's success.

Withdrawal

The process that occurs when employees begin to distance themselves from the organization by working less hard and planning to quit.

Source: Information from Benjamin Schneider, Paul J. Hanges, D. Brent Smith, and Amy Nicole Salvaggio, “Which Comes First: Employee Attitudes or Organizational Financial and Market Performance?” Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (2003): 836–851.

Withdrawal is a progressive process whereby an employee who is dissatisfied pulls away from the organization over time.38 Dissatisfied employees begin to provide less input39 and become less helpful toward coworkers.40 Early signs of withdrawal include increased lateness and in many cases absenteeism, and decreasing commitment, as well as a low sense of empowerment, turn into a decision to quit.41

Exit from the Organization

Many dissatisfied workers do not go on to the final step of the turnover process. Instead, they continue in their jobs. What explains why some dissatisfied workers leave while others stay?

As you might expect, one important factor that determines whether workers continue in undesirable jobs is the availability and desirability of alternative jobs. In spite of low job satisfaction, employees are likely to stay with an organization when they perceive that it will be difficult to find another job. People are also more likely to stay with their current jobs when they perceive that switching will have high economic and psychological costs. In essence, dissatisfied employees are more likely to leave when they expect it to be easy to find alternative work with pay that is equal to or higher than what they are receiving.42

Substantial evidence suggests that some people are simply more likely than others to leave organizations. Part of the reason is that some people are predisposed toward either high or low levels of satisfaction regardless of the work environment.43 A small number of employees are likely unsatisfied no matter how good a job is. People with chronically low job satisfaction tend to experience negative moods in all aspects of their lives.44 They also tend to have dysfunctional characteristics such as perfectionism that undermine their feelings of self-worth.45 A lower level of general satisfaction makes these people likely to leave jobs, but moving to a new job may not increase their long-term satisfaction with life.

Evidence also suggests that people with certain characteristics are more likely to leave an organization regardless of their level of job satisfaction. Individuals who are low on agreeableness often leave a job because they like doing things their own way. Individuals who are highly open to experience tend to leave to seek out new adventures. In contrast, conscientious employees tend to feel a higher sense of obligation, which makes them less likely to quit.46 Employees who are more averse to risk, as well as those who care less about what others think of them, are also less likely to actually quit.47

ORGANIZATIONAL PRACTICES THAT REDUCE TURNOVER

We have already seen that organizations pursuing internal labor strategies would prefer to retain employees, especially high-performing ones. Once an employee has decided to quit, it is often too late to do anything to change that individual's mind about leaving. Thus, organizations that want to reduce turnover must work to ensure that employees' needs are being met continuously. Good human resource management practices related to staffing, career planning, training, compensation, and workforce governance can help. Table 7.2 provides an overview of practices in each area that have been identified as helping to reduce turnover.

Source: Information from Thomas W. Lee and Steven D. Maurer, “The Retention of Knowledge Workers with the Unfolding Model of Voluntary Turnover,” Human Resource Management Review 7 (1997): 247–275.

Effective organizations develop ongoing procedures to find out why individuals leave. Each employee who leaves has an exit interview in which the interviewer tries to determine why the employee decided to quit. Information gained during exit interviews is used to improve organizational procedures and reduce turnover of other employees. In the rest of this section, we explore organizational procedures that can help to decrease turnover.

Exit interview

Face-to-face discussion conducted by an organization to learn why an employee is quitting.

Assessing Employee Satisfaction

Organizations seeking to reduce employee turnover frequently measure their employees' job satisfaction. Such assessments are done through surveys that ask employees about various facets of their work experience. Generally, employees can fill out the surveys anonymously. A common survey is the Job Descriptive Index, which assesses satisfaction with work tasks themselves, pay, promotions, coworkers, and supervision.48 Research has shown this index to be an accurate indicator of employee perceptions.49

Along with employees' responses, the organization collects general information about demographic characteristics, work positions, and locations. Results are then analyzed to determine average levels of satisfaction, as well as differences between departments and worksites. Analysis provides insight into areas of concern and helps organizations determine which facets of the work experience might need improvement. Business Development Bank of Canada, for example, conducts surveys to obtain assessments about employee benefits. As a result of employees' responses, the bank has offered monetary gifts, extra vacation days, and flexible work hours, increasing employee satisfaction and helping to reduce employee turnover.50

Job satisfaction surveys are best when they quickly engage employees by asking interesting questions. Topics expected to be most important to employees should be placed at the beginning of the survey. Routine questions such as length of time worked and department should be placed at the end.51 The value of employee surveys can also be increased by including items measuring how well the organization is meeting strategic objectives. For example, the survey might ask employees how well they think customer needs are being met or whether they believe the company is truly providing differentiated products and services.52

The organization's climate for diversity is something that can be particularly important to assess. People are more likely to leave groups when they perceive that they are very different from others.53 Women and racial minorities thus tend to quit more frequently than white men.54 Retention of women and minorities is higher in organizations that value and support diversity.55 But the benefits don't stop with retention; a supportive climate for diversity can also reduce absenteeism and increase performance.56 Organizations thus benefit a great deal from measuring and improving their diversity climates.

Yet, one problem with job satisfaction surveys is that the least satisfied employees are not likely to respond to the survey. These employees have already started to withdraw from the organization, so they see little personal benefit in completing the survey. They see things as too negative to fix, and they no longer care about the work environment of the company they are planning to leave. Organizational leaders are thus wise to remember that job satisfaction results will likely make things appear more positive than they really are.57

Socializing New Employees

Efforts to retain employees should begin when they are hired, as there is a tendency for new employees to feel a lack of support within a few months of joining an organization.58 An important process for new employees is socialization, the process of acquiring the knowledge and behaviors needed to be a member of an organization.59 Effective socialization occurs when employees are given critical information that helps them understand the organization. Finding out things such as how to process travel reimbursements and whom to ask for guidance helps to make employees feel welcome in the organization. As employees acquire information during the socialization process, their feelings of fit with the organization increase,60 and employees who perceive that they fit are more likely to stay with an organization.61 A key to effective socialization is the opportunity for new employees to develop social relationships by interacting with coworkers and leaders. Orientation meetings, mentoring programs, and social events are thus important tools for reducing employee turnover.62 As explained in the “Technology in HR” feature, much of the benefit of these programs comes from interactions with others that build a sense of social support.

Socialization

The process in which a new employee learns about an organization and develops social relationships with other organizational members.

Building Perceptions of Organizational Support

Another factor that influences employee turnover is perceived organizational support—employees' beliefs about the extent to which an organization values their contribution and cares about their well-being. Employees who feel supported by the organization reciprocate with a feeling of obligation toward the organization.63 Employees who perceive greater support are more committed to sticking with the organization and feel a stronger desire to help the organization succeed.64 This sense of obligation reduces absenteeism and turnover.65 For instance, Fraser's Hospitality, a hotel organization in Singapore, has achieved below-average turnover by creating a work culture that encourages a sense of personal worth and dignity. Treating service workers such as housekeepers and technicians with respect, as well as spending substantial amounts of money on training and development, has helped Fraser's generate higher profits by increasing occupancy at its hotels.66

Perceived organizational support

Employees' beliefs about how much their employer values their contributions and cares about their personal well-being.

A number of organizational characteristics and practices increase perceptions of organizational support. Actions of organizational leaders are particularly important. Employees feel greater support from the organization and are less likely to quit when they feel that their supervisor cares about them and values their contributions.67 Better compensation practices, better-designed jobs, fairness of procedures, and absence of politics are also critical for building perceptions of organizational support.68 In the end, businesses that employees view as having fairer human resource practices have higher employee commitment and lower rates of employee turnover.69 Organizations can therefore improve employee retention through effective human resource practices related to leadership, work design, compensation, and performance appraisal.

Selecting Employees Who Are Likely to Stay

One way to reduce employee turnover is to avoid hiring people who are likely to quit. An example of a company that does this effectively is FreshDirect, which is profiled in the accompanying “Building Strength Through HR” section. Recognizing and selecting employees who are likely to stay is critical for organizations. Realistic job previews, which we discussed in Chapter 5, offer one method of screening out people who are likely to quit. Realistic previews provide job applicants with both positive and negative information about the position. A clearer understanding of the job and the organization can help employees better determine whether the position is right for them. Employees who have more realistic expectations about the job are less likely to quit.

Another method of reducing turnover is to directly assess individual differences. We have already seen that some people have characteristics that make them more likely to quit than others. People who spent less time in their last job are more likely to quit, for example. Specific scales that directly ask how long an applicant plans to stay with the organization or that assess certain specific characteristics have also been found to predict who quits.70 A good example of using selection practices to reduce employee turnover is Via Christi Senior Services, which operates a number of health centers for older people in Kansas and Oklahoma. Via Christi uses an online screening tool that assesses individual characteristics, such as personality. Use of the screening tool helps Via Christi reduce employee turnover and save approximately $250,000 each year.71

Promoting Employee Embeddedness

The paths to turnover shown in Figure 7.3 suggest that an employee's decision to quit is often set in motion by an initial shock. Organizations can thus reduce dysfunctional turnover by insulating employees against such shocks. One method of insulating against shocks is to encourage embeddedness, which represents the web of factors that ties the individual to the organization. Not surprisingly, organizations with Loyal Soldier and Committed Expert HR strategies tend to have employees who are more embedded.72 People are more embedded when they have strong connections to others, when they have values and goals that fit with their environment, and when they feel that leaving would result in monetary or psychological losses.73 People become embedded not only in organizations but also in the communities where they live. People, particularly women, are less likely to leave when they are embedded in either the specific organization or the surrounding community.74

Embeddedness

The extent to which an employee is tied to an organization and to the surrounding community.

Some organizations are better than others at promoting embeddedness. To promote embeddedness, organizations can provide enjoyable work, desirable work schedules, strong promotional opportunities, and good benefits, as well as encouraging employees to build positive social relationships with coworkers. Organizations use a number of specific approaches to do this. Encouraging employees to work in teams helps develop strong social relationships within the organization. Company-sponsored service projects and athletic teams build similar relationships in the community. To increase the sacrifice associated with leaving, compensation packages can reward employees for continuing with the organization for several years. Providing desirable perks such as tickets to athletic events and company vehicles can also reduce turnover by increasing embeddedness.75 As explained on the previous page in the “How Do We Know?” feature, an individual is also less likely to quit when coworkers are embedded.

Helping employees balance their work and family responsibilities is a particularly strong method of increasing embeddedness. As discussed in Chapter 4, employees with family roles that conflict with work roles experience less job satisfaction.76 In addition, job satisfaction and general life satisfaction are related, so conflict between work and family roles reduces happiness both on and off the job.77 Indeed, mental health concerns are greater for people who experience conflict between work and family responsibilities.78 Organizational policies and programs such as onsite daycare and flexible work scheduling thus increase embeddedness by reducing conflict between work and other aspects of life.

How Do Layoffs Affect Individuals and Organizations?

Large-scale terminations of employment, which are not a response to individual employees performing poorly, are known as layoffs.

Layoffs

Large-scale terminations of employment that are unrelated to job performance.

Unfortunately, layoffs happen fairly frequently. Almost everyone has a friend or family member who has lost a job in a layoff, and newspaper stories about companies laying off employees are common. This section discusses the effects of layoffs on both organizations and workers. It also describes steps that organizations can take to reduce the negative consequences of layoffs.

THE EFFECT OF LAYOFFS ON ORGANIZATIONS

Many organizations lay off employees as part of an overall change effort. In some cases, the need for change comes from shifting demand for products and services. People no longer want to buy as much of what the organization produces. In other cases, competition from rival organizations forces the organization to develop more efficient processes. When an organization engages in widespread layoffs intended to permanently reduce the size of its workforce, it is said to be downsizing.

Downsizing

Widespread layoffs with the objective of permanently reducing the number of employees.

Downsizing has been promoted as a practice that can help an organization shift direction and reorient itself in relation to its customers. An important question, then, is whether downsizing and the associated employee layoffs are actually helpful for organizations. What happens to organizations that lay off workers? Do they really change for the better? Does downsizing help the organization become more efficient and more profitable?

The fact is, the effects of downsizing on organizations are not altogether clear. An organization's reputation is usually harmed by downsizing.79 Yet, research suggests that the financial performance of organizations that have downsized is similar to the performance of organizations that have not downsized. This finding both supports and challenges the effectiveness of downsizing. Firms are usually not performing well when they pursue downsizing, so finding that their performance is similar to that of competitors after downsizing suggests that layoffs may initially improve profitability. Yet, firms that use downsizing do not have higher performance in subsequent years. This suggests that downsizing may not help an organization become more efficient and increase long-term productivity.80

Furthermore, the effect of downsizing is not the same for all organizations. Some organizations appear to benefit more than others. About half the firms that downsize report some benefit, whereas half report no improvement in profits or quality.81 Downsizing is most harmful to organizations with long-term employment relationships: those pursuing Loyal Soldier and Committed Expert HR strategies.82 Downsizing also seems to present the most problems when an organization reduces its workforce by more than 10 percent and makes numerous announcements of additional layoffs.83 Moreover, reasons behind downsizing seem critical. Firms that downsize as part of a larger strategy to change before problems become serious are generally valued more by investors than firms that downsize after problems have already occurred.84 In the end, then, downsizing alone is not as effective as downsizing combined with strategic efforts to change.85 For example, downsizing that eliminates supervisory positions and reduces hierarchy seems to be particularly beneficial.86

THE EFFECTS OF LAYOFFS ON INDIVIDUALS

Being laid off from a job is a traumatic experience. Work provides not only an income but also a sense of security and identity, which are critical for psychological health. But the impact of downsizing goes beyond those who lose their jobs. Widespread layoffs can also have a negative effect on employees who remain with the organization.

Consequences for Layoff Victims

Layoff victims—the individuals who actually lose their jobs—experience a number of problems. Job loss begins a chain of negative feelings and events, including worry, uncertainty, and financial difficulties. Layoff victims are likely to suffer declines in mental health and psychological well-being, as well as physical health. They also experience less satisfaction with other aspects of life, such as marriage and family life.87

Layoff victims

Individuals whose employment is terminated in a layoff.

As we might expect, people who spend more effort on finding a new job are more likely to be reemployed quickly.88 Unfortunately, those who work the hardest to find a new job often suffer the most negative consequences to their physical and mental well-being, as efforts to obtain a new job often result in rejection and frustration.

Figure 7.5 illustrates how individuals cope with job loss:

- Individuals with high work-role centrality, which is the extent to which work is a central aspect of life, derive much of their life satisfaction from having a good job. These individuals suffer more from job loss than do individuals for whom work is less important.

Work-role centrality

The degree to which a person's life revolves around his or her job.

- Individuals who have more resources cope better. Common resources include financial savings and support from close friends and family members.

- Mental perceptions are also critical. Individuals who have positive perceptions of their abilities to obtain a new job, and who perceive that the job loss did not result from something they did wrong, cope better than others.89

- Strategies for coping with job loss can also affect individual well-being. People who focus their efforts on solving problems and who deal constructively with their emotions have fewer health problems. People who feel that they can control the situation and obtain a new job are less harmed than those who perceive that they have little personal control.90 Setting goals, proactively managing emotions, and being committed to getting back to work also facilitate reemployment.91

The quality of the job the victim finds to replace the one lost is another important factor in determining the long-term consequences of a layoff. Individuals who find new jobs that they enjoy, and that pay well, are less traumatized by the experience of job loss.92 Perceptions of fairness surrounding the layoff process also have a critical impact on how victims experience a layoff.93 Organizations should thus strive for fairness during the layoff process.

Figure 7.5 Coping with Job Loss and Unemployment. Source: Adapted from Frances M. McKee Ryan, Zhaoli Song, Connie Wanberg, and Angelo J. Kinicki, “Psychological and Physical Well-Being During Unemployment: A Meta-Analytic Study,” Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (2005): 56. Adapted with permission.

Consequences for Layoff Survivors

Layoff survivors are employees who continue to work for the downsizing organization. It seems better to be a survivor than a victim. However, even those whose jobs are not eliminated often react negatively to downsizing.

Layoff survivors

Individuals who continue to work for an organization when their coworkers are laid off.

In many ways, survivors' reactions are similar to victims' reactions. Like victims, survivors can have negative reactions, including anger at the loss experienced by coworkers and insecurity concerning the future of their own jobs. Survivors may also experience some positive emotions, however. They might feel relief that their own jobs were spared. These feelings result in a number of possible outcomes related to job satisfaction, commitment to the organization, and work performance.94

One possible reaction of employees who survive a layoff is increased motivation and performance. In some cases, individuals who remain employed feel an obligation to work harder to show that their contributions are indeed more valuable than the workers who were let go.95 However, this effect does not occur for all survivors. Effort increases the most for survivors who perceive a moderate threat to their own jobs. If people feel that their jobs are completely insulated from future layoffs, or if they believe it is only a matter of time before their own jobs are eliminated, they are unlikely to increase their efforts. Employees who are the primary wage earners in their households are also more likely to increase their efforts after observing coworker layoffs.96

Even if they increase their performance, many survivors suffer in terms of psychological and emotional health. Anxiety, anger, and fear lead some individuals to withdraw from the organization. In addition, fewer workers mean greater work responsibilities for those who remain, resulting in greater stress among workers.97 Many who were not laid off begin to search voluntarily for new jobs.98

Figure 7.6 Relationships Between Fairness, Reasons for Downsizing, and Organizational Commitment. Source: Based on information from Dirk van Dierendock and Gabriele Jacobs, “Survivors and Victims, a Meta-Analytical Review Of Fairness and Organizational Commitment after Downsizing,” British Journal of Management 23 (2012): 96–109.

Similar to victims, an important factor in determining whether survivors will react positively or negatively is the fairness that they perceive in the layoff procedures. Survivor commitment is highest when employees who remain perceive that terminations were carried out with fair procedures. For example, survivors react more positively when they feel that victims received adequate compensation.99 As shown in Figure 7.6, fair procedures are particularly important when organizations are located in countries with cultures of individual achievement and when the motive behind a layoff is seen as profit maximization. Effective human resource management practices that ensure fair treatment and provide surviving employees with opportunities for personal development are therefore critical for reducing the negative impact of downsizing.100

REDUCING THE NEGATIVE IMPACT OF LAYOFFS

The best method for reducing the negative impact of layoffs is to avoid them. The value of avoiding layoffs was illustrated in the U.S. airline industry following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The attacks reduced demand for air travel and forced airlines to explore methods of reducing costs and increasing efficiency. Some airlines included downsizing as part of these efforts. Other airlines with financial reserves and good strategic plans did not need to downsize. Those that did not downsize were more effective in the long run.101 Having a clear plan and accurately forecasting labor needs can help reduce the need for layoffs.

Of course, maintaining employee count isn't always possible. Table 7.3 presents a summary of alternatives to layoffs. When layoffs are unavoidable, laying off low performers is generally more effective than laying off employees across the board. Not hiring new workers when current employees voluntarily quit or are terminated for cause can effectively reduce the employee count. Many organizations also encourage early retirement. The natural process of not replacing people who leave is less painful than layoffs, but this strategy can take a long time if employees don't leave the organization very often.

Sources: Information from Matthew Boyle, “Cutting Work Hours Without Cutting Staff,” BusinessWeek 4122 March 9, 2009, p. 55; Beth Mirza, “Looking for Alternatives to Layoffs,” Society for Human Resource Management, available online at http://www.shrm.org/hrdisciplines/businessleadership/articles/pages/alternativestolayoffs.aspx.

Another solution is to reduce or eliminate overtime. Yet another is to ask employees to share jobs, so that each works fewer hours than a normal workweek. Although working fewer hours will reduce employees' pay, total job loss would reduce it much more. Employees might also be transferred to other parts of the organization that are experiencing growth. Such transfers often allow an organization to change while retaining high-quality workers. Finally, organizations can have their employees perform tasks that were previously contracted to outside firms.102

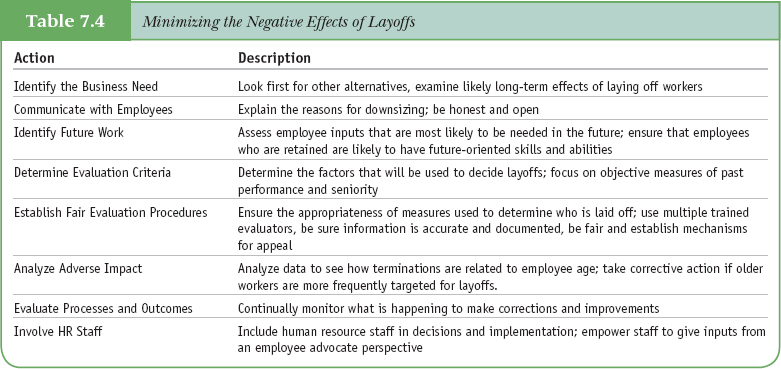

When layoffs are necessary, effective communication of downsizing decisions and plans is particularly critical. Table 7.4 provides specific guidelines for making announcements about layoffs.103 Too often, organizations make the mistake of not involving employees in the decision process. Being honest and giving employees access to information can help alleviate many of the negative consequences of downsizing.104 Organizational leaders who carefully plan the announcement process are more likely to be perceived as fair and to retain the support of both layoff victims and survivors.

Source: Information from Michael A. Campion, Laura Guerrero, and Richard Posthuma, “Reasonable Human Resource Practices for Making Employee Downsizing Decisions,” Organizational Dynamics 40 (2011): 174–180.

Understanding legal issues is also important for successful downsizing. Layoffs must be completed without discrimination. Analyses should be conducted to determine the impact of layoffs on women, members of minority groups, and older workers. As mentioned in Chapter 3, layoffs often have more impact on older workers. Replacing older workers with younger workers is illegal in many cases and may open the organization to allegations of discrimination. Once again, the fairness with which employees are treated is an important predictor of legal actions. Layoff victims perceive less discrimination when their supervisors communicate with them honestly.105

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4

What Are Common Steps in Disciplining Employees?

Unfortunately, sometimes employees fail to carry out their duties in an acceptable manner. We have already seen that retaining employees who do not perform at an adequate level is harmful to an organization, particularly when the organization is pursuing a differentiation strategy. Of course, it is usually wrong to terminate problem employees without giving them a chance to improve. The process whereby management takes steps to help an employee overcome problem behavior is known as discipline. In essence, discipline is instruction with the purpose of correcting misbehavior.

Discipline

Organizational efforts to correct improper behavior of employees.

The world of sports provides some high-profile examples of discipline. Almost every college football team has suspended players for violating team rules. Professional athletes are frequently suspended from practice and games for violating substance-abuse policies. Each instance of drug use results in a greater penalty, and players who continue to violate the rules may be expelled from the team and the league. Athletes, whether at the college or professional level, are representatives of their organizations who are expected to follow a certain code of conduct. Discipline is the corrective action that occurs when the code is not followed. The ultimate goal of discipline is to change behavior and help the individual become a contributing member of the team.

Most organizations and workplace leaders face similar discipline problems with employees, although these problems are less public. Employees who are not meeting organizational expectations are disciplined as part of a process aimed at changing undesirable behavior. Organizations whose employees belong to labor unions generally work with union officials to administer discipline. We will discuss this process in Chapter 13. Most other organizations adopt formal discipline procedures based on the notion of providing due process.

PRINCIPLES OF DUE PROCESS

Due process represents a set of procedures carried out in accordance with established rules and principles. The underlying intent of due process is to make sure employees are treated fairly. A number of court cases and decisions by labor arbitrators have established a set of principles, summarized here, that organizations should follow to provide due process for employees.106

Due process

A set of procedures carried out in accordance with established rules and principles and aimed at ensuring fairness.

- Employees have a right to know what is expected of them and what will happen if they fail to meet expectations. A production employee should not be punished for failing to clean a machine if she is not aware that the machine needs cleaning. Effective discipline requires that organizations communicate clear expectations for acceptable behavior.

- Discipline must be based on facts. Reducing a steel worker's pay for being consistently late to work is improper unless evidence shows that he has actually been late a specific number of times. Disciplinary actions should be carried out only after a careful investigation of the facts and circumstances. Fair investigations involve obtaining testimonial evidence from witnesses and those involved. Documents and physical evidence can also provide key details to either support or refute allegations against employees.107

- Employees should also have a right to present their side of the story. A sales representative accused of falsifying expense reports must be given a chance to explain his financial records. Employees should also have the right to appeal decisions. Providing the opportunity for another person to evaluate the facts of the case and the decision of the supervisor is important for ensuring fair and consistent treatment.

- Any punishment should be consistent with the nature of the offense. Perhaps an employee who becomes angry with a single customer should not be fired. The procedures used to investigate the alleged offense and the nature of the punishment should also be consistent with common practices in the organization. Disciplining an individual for doing something that is routinely done by others who go unpunished can be evidence of discrimination against the person receiving the discipline.

THE PROCESS OF PROGRESSIVE DISCIPLINE

Some forms of misconduct are so serious that they result in immediate termination of an employee. For instance, it might be appropriate to fire an employee who physically attacks a client. Stealing from the company might also be grounds for immediate dismissal. In such cases, due process generally allows termination of employment once the facts have been discovered. However, most offenses are not serious enough to warrant immediate dismissal, and in these cases, due process requires the organization to allow employees to correct their misbehavior. In the interest of giving employees an opportunity for improvement, as well as clearly conveying expectations for behavior, most organizations have adopted a process of progressive discipline.

Progressive discipline

Discipline involving successively more severe consequences for employees who continue to engage in undesirable behavior.

In the progressive discipline process, management provides successively more severe punishment for each occurrence of negative behavior. A supervisor meets and discusses company policy with an employee the first time an unacceptable behavior occurs. No further action is taken if the misbehavior is not repeated. The employee is punished if the misbehavior is repeated. Subsequent instances of the misbehavior are met with harsher punishment that eventually results in termination of employment.

Although the number of steps and actions differ by organization, most progressive discipline systems include at least four steps.108 Figure 7.7 presents the four basic steps.

The first step is a verbal warning. The supervisor clearly communicates what the employee did wrong and informs the employee of what will happen if the behavior occurs again. If the behavior is repeated, the employee receives a written warning. This warning is usually placed in the employee's personnel file for a period of time. A repeat of the behavior after the written warning leads to suspension. The employee cannot come to work for a period of time and in most cases will not be paid. A suspension is usually accompanied by a final written warning that clearly states the employee will be dismissed if the behavior occurs again. The final step is discharge from the organization.

The concept of progressive discipline thus emphasizes the need for organizations to allow employees an opportunity to correct inappropriate behavior. This is a time when human resource professionals can help mediate potential conflicts if the employee does not respond to the manager's requests for changes in behavior.

Figure 7.7 Steps for Progressive Discipline.

A common problem associated with progressive discipline is that supervisors are sometimes unwilling to take the first step in the process. Most supervisors, like the rest of us, seek to avoid conflict. As a result, they often ignore instances of misbehavior. (If you don't believe this, just think of group projects you complete as part of your university classes. A low-performing group member is seldom confronted by teammates.) Managers are also reluctant to discipline employees when they perceive unfairness in the disciplinary process, as explained in the “How Do We Know?” feature. Developing fair procedures is thus critical. Managers are also more likely to discipline employees when they know they will be supported by leaders above them in the organization, when they have been trained to deliver discipline properly, and when there is a pattern of constructive discipline within the organization.109

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 5

How Should Employee Dismissals Be Carried Out?

Having to dismiss employees is one of the most difficult tasks that a manager faces. Just think how much people's lives change when their employment is terminated. Suddenly, they don't have scheduled activities that fill their time; they no longer interact frequently with some of their closest social contacts; and of course, their source of financial security is gone. When employees are terminated, organizations often use outplacement services to help them both cope with emotional struggles and obtain new employment. Nevertheless, the actual dismissal of an employee is usually done by the employee's manager with help from the human resources department.

OUTPLACEMENT SERVICES

Outplacement services provide employees who have been dismissed from an organization with assistance in finding new jobs. In many cases, outplacement services are provided by outside firms. An outside firm is often in a better position to work with dismissed employees, since these employees may feel some resentment toward the organization that dismissed them. Indeed, displaced workers who receive outplacement assistance from an outside source generally experience more positive reactions and are more likely to find a position that is comparable to the job that was lost.110

Outplacement services

Professional assistance provided to help employees who have been dismissed to cope with job loss and find new positions.

Outplacement services normally include testing and assessments to help displaced workers understand the type of work for which they are most qualified. Employment counselors provide guidance to improve job search skills in areas such as résumé preparation and interviewing. Many outplacement firms offer financial planning advice. Psychological counseling to deal with grief, anger, and anxiety is also frequently provided not only to displaced workers but also to their spouses. Finally, some outplacement firms provide actual job leads.

THE DISMISSAL MEETING

Outplacement services can help alleviate some of the anxiety associated with job loss. Nevertheless, the actual event in which a person is told that his or her employment is being terminated is highly stressful. Managing this event in the right way is critical if the organization is to show respect for employees and maintain a good reputation.

An example from Radio Shack a few years back illustrates how not to fire employees. One day, 400 employees opened their email accounts to learn that they had been dismissed from the company. The messages reportedly read, “The workforce reduction notification is currently in progress. Unfortunately, your position is one that has been eliminated.” Sending such traumatic news via email is insensitive to the needs of employees and has been widely criticized.111

Because of the emotional nature of dismissal, face-to-face meetings are usually best. Most experts also agree that employees should not be dismissed on a Friday. A late-week dismissal leaves the terminated employee with two days of time before actions can be taken to recover from the bad news. Dismissals early in the week allow the individual an opportunity to get right to work at finding a new job and reduce the amount of time thinking about how bad things might get.

A few key principles should guide communication during the dismissal meeting.112 In most cases, it is best to have a third person present to serve as a witness. It is important to tell the employee directly that he or she is being dismissed. Although many managers find it difficult to convey the news, an effective dismissal requires a clear statement that the person's employment is being terminated. In addition, the meeting should be brief. If principles of due process have been followed, the employee should already know why he is being fired. The dismissal meeting is not a time for a lengthy discussion of how things might have been different.

Once the bad news has been delivered, the manager should listen to the employee who is being dismissed. There is no need for the manager to argue or to defend the action. This is an emotional moment, and some individuals will simply need to vent their frustration. Finally, it is usually best to present a written summary of the meeting to the employee being dismissed. The summary should include information like when the last day of employment will be, how to return company equipment such as keys and computers, and what will happen to health insurance and other benefits.

The dismissal meeting should include a discussion of severance compensation if it is being offered. Severance compensation provides money to help cover living expenses during the upcoming period of unemployment. In many cases, severance compensation is given only if the dismissed worker agrees in a contract not to pursue legal action against the company for discrimination or other reasons.

Severance compensation

Money provided to an employee as part of a dismissal package.

The safety of the supervisor and other workers has become an increasingly important consideration. When possible, security personnel should be alerted before a dismissal takes place. They can plan to provide assistance if the person becomes violent or makes threatening statements. Security personnel should be close at hand if past behavior suggests that the person being terminated will react in a violent manner. The dismissed employee may also need to be escorted from the work site if the organization works with highly sensitive information or if the employee is being terminated for offenses such as theft or violence with coworkers.

Employee retention is critical for organizations pursuing internal labor strategies. Competitive advantage for an organization with a Committed Expert HR strategy comes from retaining employees who develop specialized skills that allow them to be more productive than employees working for competitors. Organizations with a Loyal Soldier HR strategy save money by offering job security in place of high wages.

Effective employee separation is important for organizations with differentiation strategies. A Committed Expert HR strategy involves quickly identifying low performers and encouraging them to leave rather than pursue a career with the organization. For organizations with a Free Agent HR strategy, frequent turnover of employees is expected and is often helpful for ensuring that employee skills are up-to-date.

Employee turnover usually begins with a specific event that causes the individual to think about leaving the organization. Sometimes, however, employees develop a general sense of dissatisfaction that eventually causes them to leave. Low job satisfaction is strongly related to employee turnover. Employees who are not satisfied with their jobs begin to withdraw from the organization and may eventually quit. Organizations can reduce turnover by conducting satisfaction surveys to identify employee concerns and needs. Socialization processes help new employees become more comfortable with the organization, and building perceptions of organizational support among employees increases their sense of commitment to the organization. Selection practices that identify individuals who are less likely to leave can reduce turnover, as can encouraging employees to build social relationships within the organization and the community.

The organizational benefits of downsizing are unclear. Downsizing is most common in organizations struggling with profitability. There is, however, little evidence of long-term improvement in organizational performance after downsizing. Individuals who lose their jobs experience a number of negative effects, including decreased psychological and physical health. Some layoff survivors may increase their individual performance, but most suffer negative psychological consequences. Organizations can reduce the negative consequences of downsizing by being fair and communicating honestly with both victims and survivors.

Employee discipline is most effective when it follows principles of due process. Due process requires that employees be clearly informed about what is expected of them. Any punishment for misbehavior should follow careful examination of facts, and the offending employee should have an opportunity to defend himself. Punishment should also be consistent with the nature of the misbehavior. Progressive discipline procedures help ensure due process. Progressive discipline moves from verbal warning to written warning, to suspension, and finally to discharge.

Having to fire someone is a difficult part of the management job. Outplacement services alleviate some of the negative effects of dismissal by helping displaced employees improve their job skills, providing emotional support, and sometimes supplying information about alternative jobs. An employee dismissal meeting can be stressful, but following proper procedures helps preserve both the dignity of individuals and the reputation of the organization. Dismissal should take place in a brief face-to-face meeting. Important facts and information about the dismissal should be written down and presented to the person being dismissed. Planning should also address the safety of other employees and the manager conducting the dismissal meeting.

Discipline 274

Downsizing 269

Due process 275

Dysfunctional turnover 257

Embeddedness 268

Employee retention 252

Employee separation 252

Exit interview 263

Involuntary turnover 257

Job satisfaction 260

Layoffs 269

Layoff survivors 271

Outplacement services 277

Perceived organizational support 264

Progressive discipline 276

Severance compensation 279

Socialization 264

Voluntary turnover 257

Withdrawal 261

Work-role centrality 270

- How can SAS compete with other software firms when its employees appear to work less than the employees at competing firms?

- Do you think a fast-food restaurant such as Arby's would benefit from reducing turnover of cooks and cashiers? What could the company reasonably do to encourage employees to stay? What problems might occur if employees stayed for longer periods of time?

- Do you think the university you attend makes a concerted effort to dismiss low-performing workers? How does the university's approach to dismissing low performers affect overall services for students?

- What are some specific events that might cause you to leave an organization without having found a different job?

- Which dimensions of job satisfaction are most important to you? Would you accept less pay to work in a job with better coworkers? How important is doing work that you find enjoyable?

- What things keep you embedded in your current situation? Are there personal and family factors that encourage you to keep your life as it is? Can you identify social relationships that might influence you to avoid moving to another university or a different job?

- Why do you think organizations that lay off workers frequently fail to improve their longterm performance?

- Some people who have been layoff victims look back on the experience as one of the best things in their lives. Why might a victim say such a thing several years after the layoff?

- Can you identify a time when a low-performing individual has not been disciplined by a leader? How did the lack of discipline affect the poor performer? How did it affect other workers or team members?

- As a manager, what would you say to a person whom you were firing?

To better understand the challenges that managers on the front lines of downsizing efforts face in delivering messages with dignity and respect, we conducted a study of a Fortune 500 company that we call Apparel Inc. (we disguised the corporation's real name to preserve confidentiality). Both line managers and HR managers at Apparel Inc. reported difficulty handling layoff conversations. For line managers, the experience was challenging for two reasons: their limited experience with dire personnel situations and their existing relationships with the affected employees. Many managers had genuine friendships with their direct reports and knew or had met their employees' families. Although HR managers tended to have more experience with terminations than line managers, they nonetheless found downsizing conversations to be difficult and emotionally unwieldy. An HR manager with years of experience handling layoff conversations made this point: “It's a pretty horrific event, frankly. It's not easy and it's never easy to get used to.” HR managers and line managers alike reported experiencing a range of negative emotions, often at a high level of intensity. Emotions ranged from anxiety and fear to sympathy and guilt—sometimes, even shame. One manager described the physical effects of anxiety both before and during the event:

Internally there is a nervous stomach, you feel on edge. Sometimes you get physically nauseous or headache. Very often the night before or after you have very bad dreams that are not necessarily related to the downsizing itself, but from the stress. There is a degree of nervousness that almost makes you have to step back and say, “I have to be calm, I can't show that I am nervous about delivering this message.”

Alongside anxiety, managers conducting layoffs experience sympathy and sadness. One manager explained: “It is very difficult from an emotional standpoint knowing you are dealing with somebody's livelihood, dealing with somebody's ego, dealing with somebody's ability to provide for their family.” Another manager concurred, emphasizing how distressing it can be to deliver the negative news:

If I am about to cry because this is upsetting me as much as it is upsetting the other individual, I am definitely going to try not to cry. But the emotion that I feel is genuine in terms of the unhappiness or the sorrow that I am feeling that I have to deliver this message to someone.

QUESTIONS

- What are some ways that managers might cope with negative emotions when they are forced to lay off employees?

- Why might someone argue that it is a good thing for managers to feel such negative emotions?

- How do you think you would personally react to the task of laying off workers?

Source: Andrew Molinsky and Joshua Margolis, “The Emotional Tightrope of Downsizing: Hidden Challenges for Leaders and Their Organizations,” Organizational Dynamics 35 (2006): 145–159. Copyright Elsevier 2006.

County General Hospital is a 200-bed facility located approximately 150 miles outside Chicago. It is a regional hospital that draws patients from surrounding farm communities. Like most hospitals, County General faces the difficult task of providing high-quality care at a reasonable cost.

One of the most difficult obstacles encountered by the hospital is finding and retaining qualified nurses. The annual turnover rate among nurses is nearly 100 percent. A few of the nurses are long-term employees who are either committed to County General or attached to the community. Employment patterns suggest that many of the nurses who are hired stay for only about six months. In fact, County General often appears to be a quick stop between graduation from college and a better job.

Many who leave acknowledge that they were contacted by another hospital that offered them more money. Exit interviews with nurses who are leaving similarly suggest that low pay is a concern. Another concern is the lack of social atmosphere for young nurses. Nurses just finishing college, who are usually not married, complain that the community does not provide them enough opportunity to meet and socialize with others their age.

Hospital administrators are afraid that paying higher wages will cause financial disaster. Big insurance companies and Medicaid make it difficult for them to increase the amount they charge patients. However, the lack of stability in the nursing staff has caused some noticeable problems. Nurses sometimes appear to be ignorant of important hospital procedures. Doctors also complain that they spend a great deal of time training nurses to perform procedures, only to see those nurses take their new skills someplace else.

QUESTIONS

- Turnover is high at almost every facility where nurses are employed. What aspects of nursing make turnover for nurses higher than for many other jobs?

- What programs do you suggest County General might implement to decrease nurse turnover? Be specific.

- How might County General work with other hospitals to reduce nurse turnover?

Examine the website for your university to locate information that guides the disciplinary actions of supervisors. If you can't locate this information for your university, visit a few websites for other universities. Examine the supervisor guidelines and answer the following questions:

- What does the university do to ensure due process?

- How many steps are in the university plan for progressive discipline? Are the steps similar to the four steps outlined in this chapter?

- What involvement does the human resource department have in cases of employee discipline?

- Does the site offer guidance for how to deal with specific instances of employee misbehavior?

- What steps can an employee take to appeal a disciplinary action?

- Are any unions involved in disciplinary procedures?

- Based on your experiences with the university, do you think supervisors actually follow the steps of progressive discipline?

Access the companion website to test your knowledge by completing a Global Telecommunications interactive role-playing exercise.