How Can Strategic Employee Training Improve an Organization?

Nearly everyone who has worked has attended a training program. Training is a planned effort by a company to help employees learn job-related knowledge, skills, and attitudes.1 The vast majority of companies offer training programs, and they come in many shapes and sizes: large group lectures given by an expert, on-the-job training delivered by a supervisor, simulations guided by a computer program, small-group projects coordinated by an executive, or online discussions with colleagues from around the country. The common element that defines training is that employees go through a structured experience that helps them to learn something they can use to improve their performance at work.

Training

A planned effort to help employees learn job-related knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

We usually equate learning with being in school. For example, when we were younger and in primary school, we gained knowledge, which includes facts and principles of all kinds. We gained physical and cognitive skills, which allow us to perform a wide range of tasks like throwing a ball, using computers, resolving interpersonal conflicts, and solving math problems. We also developed new attitudes, such as (hopefully) the belief that school is both fun and beneficial. When our experiences change our knowledge, skills, or attitudes, we call it learning. Learning, then, is a change in what we know, what we can do, or what we believe that occurs because of experience.

Knowledge

Memory of facts and principles.

Skill

Proficiency at performing a particular act.

Attitude

An evaluative reaction to particular categories of people, issues, objects, or events.

Learning

A change in knowledge, skill, or attitude that results from experience.

Of course, the truth is that we don't just learn in school, nor do we ever stop learning. We learn all the time in and out of classes, and we continue to learn throughout our lives. When we start a new job, we must learn about the industry, the company, and the day-to-day details of the position (including where to find the bathroom). To add to this challenge, companies and the jobs in them change over time. A company will get a new computer system, people will quit and new people will join, and products and services will be modified to meet changing customer demands. Most changes require that employees learn something new. So every job requires not only some learning to get started but also continued learning to avoid falling behind.

Most organizations, regardless of size and industry, offer at least some formal training to help employees learn.2 In a manufacturing setting, for instance, new employees can receive training on how to operate their equipment safely and effectively. Employees can learn in other, less formal ways, such as by watching others, asking for help, experimenting, or studying on their own.3 These informal methods can be effective and inexpensive, so some firms rely heavily on informal learning. Small firms, in particular, often expect their employees to learn mostly through informal means.4

While informal learning methods can work, they are not always appropriate. What if new employees at an automotive parts manufacturing facility were asked to learn all about metal stamping on their own? This process involves using large and dangerous equipment to shape metal products such as pipes. If an employee were injured because the company had not prepared him to use the equipment, then the company could be held liable for the injury. Formal training is also useful because it ensures that everyone learns the same things, such as the most efficient and most safe ways to perform a task.

Informal learning methods

Natural learning that is neither planned nor organized.

Training, when designed and delivered properly, can improve the overall effectiveness of an organization in three ways.5 First, it can boost employees' commitment and motivation. Opportunities to learn new skills are important in today's economy, so employees appreciate learning opportunities offered by training. As a result, companies that offer more training foster employee commitment.6 To be more precise, organizations that offer employees opportunities to learn and grow are seen as having employees' best interests at heart, and as a result, employees feel more committed to the organizations.7 Employee commitment also can benefit an organization by increasing retention of high-performing employees (see Chapter 7).

Second, training helps employees perform their work more effectively and efficiently, so the organization is able to function better on a day-to-day basis. If you've ever been to a grocery store where the cashier had not been trained to use the cash register efficiently, then you've been a victim of poor training (or, if you were really unlucky, it might have been a combination of poor employee selection and poor training). Research is very clear on this point—employees who receive training know more and are able to do more than employees who do not receive training.8

These first two benefits should come as no surprise given research findings about the commitment HR strategy discussed in Chapter 2. Providing employees with formal training is a key element of commitment-based HR.9Furthermore, providing training adds value beyond other HR practices. All other things being equal, providing training to a larger percentage of a company's workforce will increase that company's overall productivity.10 Employees who are trained are more likely to be committed to the organization and have higher levels of knowledge and skill. As a result, they are better individual performers, and this helps the organization to be more productive.

The third way training benefits organizations is by helping them to meet their strategic objectives. It does so by providing employees with the specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to achieve designated strategic goals. This benefit is more subtle, and it's about alignment of training activities to the organization's overall strategy and specific goals that follow from it. If an organization aligns training effectively, it will have the right people with the right skills necessary to pursue the competitive advantage sought by the strategy.

An example of a company that uses training effectively is Rockwell Collins. A leading supplier of aviation electronics equipment, Rockwell Collins is consistently faced with pressures to reduce design time of new products (in order to keep pace with new technology) and to improve quality of current products (in order to reduce equipment failure). Faced with these challenges, Rockwell Collins continuously examines bottlenecks in moving from initial design to final products, looking for ways to speed up the process and improve quality.

A common bottleneck in the Rockwell Collins product design process was delays caused by electromagnetic interference (EMI), which often results in destruction of electronic parts. The company estimated that it was losing at least $1 million a year because of EMI. A quick investigation into the causes of the problem revealed that many testing engineers lacked a basic understanding of how to avoid EMI. Working with a training company called Strategic Interactive, Rockwell staff developed a 12-hour CD-ROM course that was delivered to 1,300 engineers in about six months. Delivering the training via CD-ROM meant a larger up-front cost for developing the course, but it allowed Rockwell to train engineers more quickly. Engineers could do the training on their own time without taking time away from work to travel to corporate headquarters.

Although the course cost nearly $500,000 to develop, the end result was worth the cost. The EMI problem disappeared, and Rockwell has avoided approximately $1 million in equipment losses every year since the training. The investment in training paid off for Rockwell, and it helped the company to implement its strategy to reduce the time it takes to design new products.

How Is Employee Training Strategic?

As we've just seen, training offers universal benefits for improving employee motivation, commitment, and job performance. Training can also be aligned with strategy to help an organization gain a competitive advantage over other organizations. Training needs and training resources thus vary across firms depending on the business strategy that they pursue.11 Figure 9.1 summarizes some of these differences.

DIFFERENTIATION VERSUS COST LEADERSHIP STRATEGY

Let's first consider how training efforts should be aligned with the cost and differentiation strategies described in Chapter 2. A cost leadership strategy, including both the Bargain Laborer and Loyal Soldier strategies, requires that employees have knowledge, skills, and attitudes that help reduce costs and improve efficiency. For example, a local restaurant that is trying to compete based on low-cost menu items must have employees who know how to do their work efficiently with little waste. In other words, they must have the knowledge and skill needed to prepare and serve food quickly. Employees should also believe in efficiency and cost reduction and have a positive attitude toward working quickly. As a result, training for employees at this restaurant should not only build knowledge and skill so employees can work quickly without creating waste, it should also convince employees it is important to do so. The efforts of this small restaurant are, on a much larger scale, what companies like Motorola, General Electric, and Samsung Electronics are trying to accomplish with training programs designed to measure and improve quality. By training their employees on quality control principles and practices, these companies have been able to become more efficient, thereby reducing costs and increasing profits.12

Figure 9.1 Strategic Framework for Employee Training.

A differentiation strategy, including both Free Agent and Committed Expert strategies, requires that employees be able to deliver services or make products that are superior to the services or products offered by competitors.13 Some companies differentiate via innovation—constantly staying ahead of the competition with new products and services. With this type of differentiation, team-focused creativity training is a useful way to help employees share knowledge and build creative products. Coach, 3M, and General Mills are examples of companies that pursue this type of differentiation strategy and rely on this type of training. Differentiation can also be achieved via excellent customer service. For example, consider a different local restaurant trying to compete based on excellent service. This restaurant will train its employees how to impress customers by being considerate, friendly, and prompt. The efforts of this restaurant are similar to the efforts of companies like Nordstrom, Disney, Ritz-Carlton, and WorldColor.14 The training efforts that Apple uses at its retail stores are offered as a detailed illustration in the “Building Strength Through HR” feature.

INTERNAL VERSUS EXTERNAL LABOR ORIENTATION

Training efforts must also be aligned with the relative emphasis the organization places on internal versus external labor orientations. As you know, a company with an internal labor orientation seeks to make its own talent, whereas a company with an external labor orientation seeks to buy talent that is already developed. These different orientations clearly influence how much time and money a company will spend on training. Companies with an internal labor orientation are willing to spend time and money to train current employees, while companies with an external orientation tend instead to hire new employees to fill their needs.

For example, consider a company with an internal labor orientation that discovers managers are not following appropriate labor laws in their recruiting and hiring (covered in Chapter 3). With an internal labor orientation, the company is likely to see this as a knowledge deficit that should be addressed by training managers on these laws. An alternative approach, and one that might be adopted by a company with an external labor orientation, would be to centralize employee selection and hire a labor attorney to coordinate processes and enforce compliance with laws.

The distinction between internal and external labor orientation can also play out at an organizational level when a company decides whether to train employees for new business opportunities or acquire a new company. As an example of an external orientation, consider Adobe's acquisition of Macromedia in 2005. Adobe was the world leader in static documents on the Internet (you have probably opened and read documents in the Adobe Acrobat PDF file format). However, the company had few employees and no business units with expertise in dynamic content for the Web, such as web pages that automatically update or offer interactive displays. Rather than creating a series of training programs to help employees learn about dynamic documents, and then build that capacity into their products, Adobe chose to buy that expertise. By acquiring Macromedia (which created Flash Player, a commonly used program that runs dynamic content on the Internet), Adobe was able to increase its capacity to compete in the software industry.15 Adobe acquired this expertise rather than developing it via training.

Do companies with external labor orientations skip training altogether? The answer is clearly no. In such companies, training programs are still offered for a variety of reasons, particularly to help employees learn company-specific knowledge and skills. However, in such firms, HR management must find ways to keep training costs low. One way to do this is to purchase a training course that has already been designed. HR management first should verify that the course is relevant to their organization and potential trainees. If the material is relevant, then purchasing an existing program can be dramatically less expensive than developing a program from scratch. For safety training, for example, the National Safety Council sells self-study books, videos, and DVDs that cover such topics as Defensive Driving, First Aid, Motorcycle Safety, Electrical Safety, and Fire Protection. Most of these courses cost less than $50.16 Even better from a cost perspective, some government agencies provide free online tools that can be used as instruction, such as the U.S. Department of Labor's programs on eye and face protection, respiratory protection, lockout/tagout, poultry processing, scaffolding, beverage delivery, baggage handling, and grocery warehousing.17

Sources: David Van Adelsberg and Edward A. Trolley, Running Training Like a Business: Delivering Unmistakable Value (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1999); National Court Appointed Special Advocate Association, “Tips to Keep Volunteer Training Costs Down,” 2001, retrieved online at http://www.casanet.org on April 4, 2007.

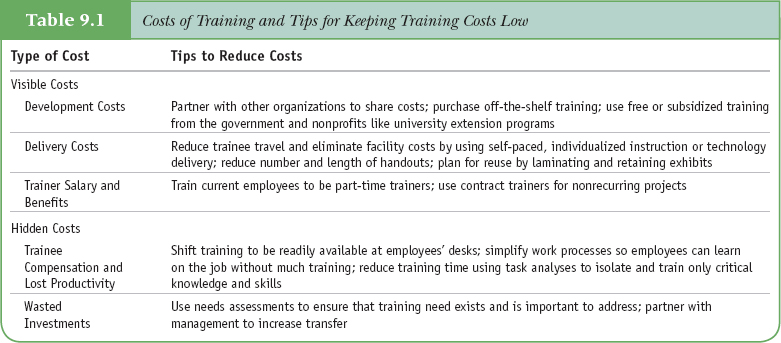

Table 9.1 provides a list of visible and hidden training costs and suggestions for how to reduce them. These tips can also be used by small businesses or any organization that needs training but also has to reduce costs.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

What Are Key Principles for Getting Benefits from Training?

Earlier, we identified three benefits an organization can gain from training its employees: Training can increase employees' commitment and motivation, it can enable them to perform better, and it can help the organization to meet its strategic objectives. To achieve these three benefits, training must result not only in learning but also in transfer of training. Transfer of training occurs when trainees apply what they have learned in training to their jobs.18 For transfer to happen, employees must first remember what they learned, or maintain an attitude over time. For example, if a trainer shows a new employee the steps involved in using a piece of manufacturing equipment, the employee must remember those steps after training is complete. Moreover, the employee must actually use those steps back on the job.

Transfer of training

Application on the job of knowledge, skills, or attitudes learned in training.

Transfer is more complicated than it sounds, and there is considerable evidence that many training programs get employees to learn but not to transfer.19 In other words, employees seem to understand the training material, but they do not change their behavior on the job. When this happens, investments in training are essentially wasted. Imagine, for example, what would have happened if Rockwell Collins's 1,300 trained engineers had finished training and done nothing differently back at work. A great deal of everyone's time and money would have been wasted, and those responsible might be trying to claim unemployment benefits.

How can training be designed to encourage learning and transfer? Two fundamental practices will help HR professionals to meet this goal: (1) managers, employees, and HR professionals must work in partnership; and (2) organizations must use a systematic process for designing, developing, and delivering training.

PARTNERSHIP

The first fundamental practice for ensuring learning and transfer is to operate training as a partnership among employees, their managers, and HR professionals. A partnership between HR professionals and employees is critical because these professionals cannot determine employees' knowledge and skill levels without their help. In addition, without the support of management, HR professionals are unlikely to be able to change the actual behavior of employees on the job. For example, if managers do not want employees to take the time to work on cost-cutting and quality-control projects, then training employees in how to run these projects is unlikely to change how the employees do their work and even less likely to improve the organization's bottom line.

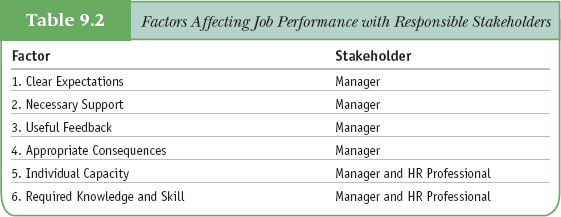

Another way to think about the need for partnership is to consider that employee performance is determined by many factors that are not under the direct control of a human resource department. Table 9.2 lists six factors that are commonly considered to have a powerful influence on job performance.

The first four factors that affect job performance are primarily the responsibility of the employees' manager. First, managers must set clear expectations about what employees should and should not do on the job. Second, managers must provide necessary support in the form of equipment, supplies, and other resources. Third, managers must provide useful feedback indicating whether employees are exceeding, meeting, or failing to meet expectations. The feedback must also guide employees toward better performance. Fourth, managers must set appropriate consequences, which means rewarding effective performance and, if necessary, punishing ineffective performance. The fifth and sixth factors, individual capacity and required knowledge and skill, are the only two factors that HR professionals have much control over. Ineffective performance on the part of any one employee, then, may be largely a function of a manager's failure to ensure that one or more of these factors are in place.

Source: Information from Geary A. Rummler and Alan P. Brache, Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995).

HR professionals can influence employees' job performance by working with managers to ensure that employees have the individual capacity (generally through recruitment and selection) and the required knowledge and skill (generally through training and development) to do the job. So the HR function does play an important role, but even in this role, there must be a partnership. If what HR professionals offer as training seems worthless to managers, then they will tell their employees to disregard training and instead do their work as it should “really be done.”

SYSTEMATIC PROCESS

The second fundamental practice used to ensure learning and transfer is to develop training systematically. There are many possible ways to develop training, but almost all have three fundamental components:

- Needs assessment to determine who should be trained and what the training should include.

- Design and delivery to ensure that training maximizes learning and transfer.

- Evaluation to determine how training can be improved, whether it worked as intended, and whether it should be continued.20

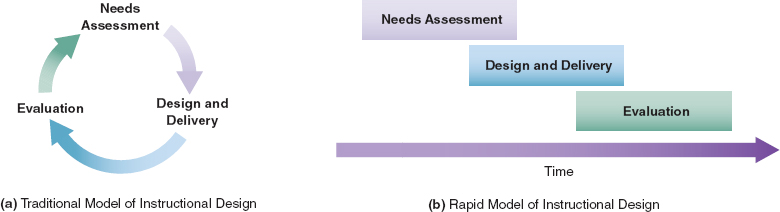

Two different forms of this three-component process are diagrammed in Figure 9.2. Part a depicts a circular process. This is the traditional model of instructional design, and it suggests beginning with a needs assessment that is followed by design and delivery and then by evaluation. Of course, the process is never complete because training needs are always changing, so after evaluation there will eventually be another needs assessment.

Traditional model of instructional design

A process used to create training programs in which needs assessment is followed by design and delivery and then by evaluation.

Part b of the figure shows the rapid model of instructional design.21 Organizations may use this version of the process when they need to speed up the time from identified need to delivery of training. In the rapid model, training design begins while the needs assessment continues, as indicated by the overlap in the bars. Just as important, training begins before the program design is completely finished, and evaluation is used to modify the training as it is developed.

Rapid model of instructional design

A process used to create training programs in which assessment, design and delivery, and evaluation overlap in time.

Figure 9.2 Two Approaches to Designing Training Programs.

Whether the traditional or rapid model is appropriate depends on the nature of the training being designed. Training that must be right the first time—either because there is only one opportunity to train particular employees or because the cost of employees doing the wrong thing is too high—should not use the rapid model. For example, training for employees who operate expensive and dangerous equipment (airplanes, cranes, bulldozers, and tanks, for example) should not be delivered to trainees unless it has been examined in great detail for accuracy and safety. Product training for retail sales employees, in contrast, could be delivered before it was perfected, and this would ensure that employees had at least some knowledge of new products as they arrived.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

How Are Training Needs Determined?

How does an organization determine what training to offer and who should be trained? This process is called needs assessment, and it occurs in two different ways.22 First, needs assessments may be done on a regular basis as training programs are planned and budgets are set. This planning process requires a proactive approach to determining training needs and developing training plans. Second, needs assessments may also be done in a reactive fashion in response to requests for particular training programs. The reactive and proactive approaches are described in more detail below.

Needs assessment

A process for determining what training to offer and who should be trained.

PROACTIVE NEEDS ASSESSMENT

Proactive needs assessment is a systematic process for determining and prioritizing the training programs to be developed and delivered by an organization. It generally has three distinct steps—organization analysis, task analysis, and person analysis.23 Each step requires different types of data.

Proactive needs assessment

A systematic process for determining and prioritizing the training programs to be developed and delivered by an organization.

Organization Analysis

Organization analysis requires information about the organization's strategic goals, environment, resources, and characteristics. With this information, an organization can determine whether certain types of training would be useful for employees and for the organization as a whole. As noted earlier, the organization's strategy is relevant to decisions about training because different strategies require different knowledge, skills, and attitudes on the part of employees. Organizations that seek to differentiate themselves from their competitors with excellent service, for example, are more likely to benefit from service-related training courses than organizations with a cost-reduction strategy. The organization's labor orientation helps to determine whether training will be seen as an appropriate way to build employee knowledge and skill.

Organization analysis

A process used to identify characteristics of the organizational environment that will influence the effectiveness of training.

Organization analysis also requires an understanding of the environment within which the organization functions. Many facets of the environment, including the technical and legal environments, influence the type of training that an organization should offer. The technical environment includes the current and future technologies that employees will use to perform their work. For example, if an organization is planning to upgrade its computer systems, it will need to plan for training to assist in the transition and will also need to change its existing training to be consistent with the new systems.

The legal environment includes both legislative and regulatory mandates. HR professionals should know how training can assist in compliance and reduce the risk of legal problems. As an example, U.S. courts have determined that the degree of an organization's liability for discrimination depends on whether managers were trained in nondiscriminatory hiring practices.24 Consequently, managerial training covering laws related to discrimination is useful for organizations covered by employment laws like the Civil Rights Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act, discussed in Chapter 3. Organization analysis should determine which laws are applicable.

Organization analysis also measures characteristics of the work environment, such as how much the organization supports its employees in attending training and using what they learned in training back on the job. Such support may take the form of policies, reward systems, management attitudes and actions, and peer support. Organizations that support training are considered to have a positive training climate. Thus, they are more likely to have employees who use learned skills back on the job, because employees are much more likely to succeed in transfer if they perceive that their organization has a supportive climate.25 If trainees will be returning to a work environment that is not supportive, they should be prepared in training with strategies that will help them overcome the lack of support. Alternatively, it may be necessary to change the climate before investing in the training. Of course, this is easier said than done, because changing climate is a difficult process that unfolds over time only with the commitment of top management.26

Training climate

Environmental factors that support training, including policies, rewards, and the attitudes and actions of management and coworkers.

It is important to note that organization analysis need not be repeated every time a proactive needs assessment is conducted, but it should be repeated if the organization or its environment changes. Changes in competitors' practices, in internal management structure, and in labor laws can alter training needs, as can mergers, acquisitions, and alliances. HR professionals should constantly monitor the environment for such changes and conduct a formal organization analysis when changes are noted.

Task Analysis

Task analysis is a form of job analysis that involves identifying the work activities performed by trainees and the knowledge and skill necessary to perform the tasks effectively (see Chapter 4). The methods used in task analysis vary depending on the task being analyzed. The most common process used when the task analysis is being done to help design training is the following:

Task analysis

A process used to describe the work activities of employees, including the knowledge and skill required to complete those activities.

- Groups of job incumbents develop lists of the tasks performed.

- HR professionals group tasks into clusters based on similarity.

- Groups of managers generate knowledge and skill statements for each task cluster.

- Surveys, given to a new sample of incumbents, verify the task, task cluster, knowledge, and skill lists.

To avoid bias in the data collection, it is generally suggested that multiple groups and multiple incumbents be involved.27 Of course, in smaller organizations or for jobs that don't exist yet, it may be impossible to get information from people already doing the job. In this case, a few of the individuals who will be responsible for the work to be done can participate. Whoever is involved, it is important to use more than one person in order to get high-quality data; any one individual may not have a complete or accurate perspective on the tasks.

There are three common variations of task analysis: competency modeling, cognitive task analysis, and team task analysis.

- Competency modeling is similar to task analysis but results in a broader, more worker-focused (as opposed to work-focused) list of training needs. The process was described in Chapter 4. Competency modeling is most frequently used with managerial jobs. One benefit of using a competency model for needs assessment is lower cost, because this type of analysis does not involve determining specific competencies for a particular job. A related drawback is that the result of competency modeling may not have sufficient detail to guide training for any one particular job.28

- Cognitive task analysis examines the goals, decisions, and judgments that employees make on the job.29 While traditional task analysis focuses on observable tasks and behaviors, cognitive task analysis delves into the thought processes that underlie effective performance of a task. Experts are asked to think out loud while they perform each step of the task. Later, the transcripts of their words are analyzed to identify the knowledge and skills that were necessary at each step.

- Team task analysis involves examining the task and coordination requirements of a group of individuals working together toward a common goal.30 It is important to use team task analysis in situations where the performance of interest to the organization is largely determined by coordinated efforts. Research on nuclear power plant operations, for example, indicates that operating teams must exchange information and share key tasks in order to perform effectively. Team task analysis will identify the knowledge and skills that underlie these exchanges. Then, training will focus on knowledge and skills identified in the team task analysis as well as the required technical skills.

Person Analysis

Person analysis involves answering three questions:

Person analysis

A process used to identify who needs training and what characteristics of those individuals will influence the effectiveness of training.

- Is training necessary to ensure that employees can perform tasks effectively?

- If training is needed, who needs the training?

- Are potential trainees ready for training?

First, person analysis should determine whether training is necessary by determining whether employees' knowledge and skill are relevant to improving their performance. If employees lack knowledge and skill required for performance, then training is appropriate. There are, however, many other reasons why employees may not perform effectively, including unclear expectations, lack of necessary support in the form of resources and equipment, lack of feedback about performance, inappropriate consequences, and lack of capacity.31 You may recall this list from Table 9.2.

Second, if training is needed, it is necessary to determine who needs training. A number of different methods can be employed to make this determination. Two of the most common are examining employee records and asking employees whether they think they need training. Both can be useful, but each suffers from potential bias. Employee records may not be sufficiently detailed or may gloss over skill deficiencies because of legal concerns over keeping records of poor performance. As to self-assessments of training needs, employees generally overestimate their skills and thus underestimate the need for training.32 Another commonly used method is to rely on supervisors to identify those who need or would benefit from training. Because no one method is perfect, multiple methods should be used when possible.

Third, HR professionals must determine if those who need to be trained are ready for training. To do this, they should examine the general mental abilities, basic skills, motivation, and self-efficacy of the potential trainees. Research suggests that individuals with higher levels of general mental ability, necessary basic skills, motivation to learn, and self-efficacy are more likely to benefit from training.33 That does not mean that training should be offered only to those who fit this profile. Training will, however, be more successful if it is adjusted for particular groups of trainees, as outlined in Table 9.3.

As one example, consider an outsourced call center where employees in another country answer phone calls from the United States. The center might develop two different training programs for employees with different levels of English-language skills. Employees with lower English-language skills may need a course that covers basic terminology and English phone etiquette before being trained on company-specific phone procedures. Assessing the basic language skills of employees will be necessary to determine whether language skill differences exist and to help assign employees to the proper training.

REACTIVE NEEDS ASSESSMENT

The analyses we have discussed are useful for proactively determining how an organization should allocate training resources. An alternative model deals with situations that involve a specific performance problem, such as low sales or high turnover. This model, reactive needs assessment, is a problem-solving process that begins with defining the problem and then moves to identifying the root cause of the problem and designing an intervention to solve it. Some organizations, like Rockwell Collins, have implemented this problem-solving process by requiring managers who request training to fill out a form. A modified version of the form used at Rockwell Collins is presented in Table 9.4. The questions on this form are designed to help managers think through whether the training requested is relevant to the company's strategy and related goals and whether training is the most efficient solution to the problem.

Reactive needs assessment

A problem-solving process used to determine whether training is necessary to fix a specific performance problem and, if training is necessary, what training should be delivered.

Source: Information from Cliff Purington and Chris Butler with Sarah Fister Gale, Built to Learn: The Inside Story of How Rockwell Collins Became a True Learning Organization (New York: AMACOM, 2003).

Some other organizations follow a three-step process. The steps are (1) problem definition, (2) causal analysis, and (3) solution implementation.34

Problem Definition

Problem definition begins with the identification of a business need. When a request for training comes in, the first question to be asked is whether the problem is important. Companies must prioritize, and it may be that the problem is not sufficiently related to the company's current strategy and goals to warrant the resources required to fix it. If the problem is sufficiently important, then the next question to be asked is, “What should be happening, and how does that vary from what is actually happening?” This means stating the problem as a gap between desired and actual performance. For example, suppose your sales team has been selling primarily inexpensive products (less than $100 per item) but management wants you to increase sales of more-expensive products (more than $1,000 per item) by 50 percent. In this case, the 50 percent difference between current sales and desired sales of expensive products represents a gap between desired and actual performance.

Problem definition

The gap between desired and actual performance.

Causal Analysis

Once a problem has been defined as a gap, it is necessary to find out the reasons for the gap. This is done through causal analysis. To understand the causes, we ask, “Why does this gap exist?” The gap may result from a lack of knowledge, a lack of motivation, a lack of feedback, or a poor environment. To determine the underlying cause of poor performance, HR professionals explore what employees are doing and why.

Causal analysis

A process used to determine the underlying causes of a performance problem.

In the case of a sales team that should be selling more-expensive products, causal analysis would determine why those products are not being sold. Is it because of a problem with the product itself or with the customers who are currently being targeted? Is it because sales employees are not motivated to make those sales, or perhaps because they are not knowledgeable enough about those products to close sales? Asking the right questions can lead to identifying a set of causes that will help determine whether training will solve the problem. If the cause is a knowledge deficit, then training can help close the gap between desired and actual results. If the cause is most likely the product or employee motivation, then a need has been identified that cannot be resolved through training.

Solution Implementation

The final step involves selecting and implementing the appropriate solution or solutions. This step includes brainstorming possible interventions, examining them for effectiveness and efficiency, and prioritizing them. Table 9.5 gives examples of possible solutions to the sales problem in our example. It is worth noting that many solutions do not involve training; training is not a useful solution to every performance problem. Note also that these solutions are categorized according to the performance factors identified in Table 9.2. Alternative solutions should be considered for their relative effectiveness (how well do we think they will work?) and efficiency (how much will they cost? how long will they take?). People familiar with the job can be asked to rate each potential solution for its anticipated effectiveness and efficiency. The solution that best balances efficiency and effectiveness should be selected for design and implementation.

PRIORITIZING AND CREATING OBJECTIVES

Once the organization has collected needs assessment information, it must put all that information together to determine what training to offer and whom to train. This part of the assessment process includes prioritizing training needs and setting objectives for training.

Determining Priorities

An organization often identifies a number of different training needs—usually more than can possibly be covered given the training budget and the time that employees can be away from their work. What can be done? Prioritize! There are a few different ways to prioritize, including ratings and interviews, but no one method is best.

Figure 9.3 shows one method for prioritizing training needs based on a task analysis. The figure lists some knowledge and skills necessary for a general manager's human resource responsibilities. A sample of managers and employees familiar with the job can be asked to rate each item on this list along two scales—strategic importance and need for training. Strategic importance is the importance of this particular item for helping the person perform his or her work effectively and in a way that benefits the entire organization. Need for training is the degree to which it is important that the person have this knowledge and skill before beginning work. A low need for training means that performers can learn as they work. Once all the ratings have been collected, they are summed to create a composite rating. Then the list is rank-ordered from highest to lowest scores. The needs that come to the top are those that are most relevant to the organization's strategy and that are required early on the job. The items highest on the list should be the focus of training.

Creating Objectives

Whether proactive or reactive needs assessment techniques are used, if training is required, then an essential output of the assessment process should be a list of training objectives. Here, an objective is simply a desired and intended outcome. Two of the most critical types of objectives are learning objectives and organizational objectives.35

Figure 9.3 Sample Prioritization Worksheet Using Knowledge, Skill, and Attitude Statements.

Learning objectives are the intended individual learning outcomes from training. For a veterinary surgeon, for example, an outcome might be knowledge of the anatomy of a particular animal or skill in using a scalpel to remove cysts. The learning objectives should be used to determine the content, methods, and media used in training (we describe these elements of training in the next section).36 Learning objectives are useful because they provide a basis for selecting features of training, provide measurable results that can be used to determine if training was effective, offer guidance to learners about what they should be doing, and ensure that, even if multiple trainers or sessions are involved, the same outcomes are achieved.37

Learning objective

The individual learning outcome sought by training.

Effective learning objectives have three components:

- Performance identifies what the trainee is expected to do or produce.

- Conditions describe important circumstances under which performance is to occur.

- Criteria describe acceptable performance in a quantifiable and objective way.

Table 9.6 gives some examples of ineffective learning objectives and the changes necessary to make them effective.

Organizational objectives capture the intended results of training for the company. These may include increased productivity, decreased waste, or better customer service. Specifying the intended organizational result of training programs helps to ensure that the training provides value to the organization as a whole and that each program is linked to the strategy of the firm. Setting organizational objectives can thus help in prioritizing. For example, if a training program has the objective of increasing customer satisfaction, but reducing costs is the primary strategic direction of the firm, then that program should be considered lower priority than a program intended to help reduce costs.

Organizational objective

The organization result sought by training.

Source: Information from Robert F. Mager, Preparing Instructional Objectives, 3rd ed. (Atlanta: Center for Effective Performance, 1997).

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4

How Is Effective Training Designed and Delivered?

Once objectives have been written, decisions must be made about content (what to deliver to trainees), methods (how to help trainees learn the content), media (how to deliver content and methods to trainees), and transfer-enhancement techniques (how to help trainees transfer what they learned back to the job).

In terms of content, organizations devote the largest proportion of training time to topics that are specific to the industry, such as computer assembly and testing at computer companies such as Dell and inventory control at clothing companies such as Old Navy. Other types of training that receive considerable time include information technology, managerial and supervisory, mandatory and compliance, business processes and procedures, quality and product knowledge, and sales. Figure 9.4 specifically illustrates the extent to which a variety of content is emphasized by a large sample of organizations in the United States. Part b of the figure also captures the type of media used and indicates that training media have changed gradually over the years to include more and more technology-based delivery, including CD-ROM and Internet-based training.

Figure 9.4 Snapshots of Training Practices in the United States.

Source: Laurie Miller, State of the Industry Report, 2012: ASTD's Annual Review of Workplace Learning and Development Data (Alexandria, VA: American Society for Training and Development, 2012), 31, 33.

CONTENT

Content is the material that is covered in training. Training objectives are used to determine what content is needed. The person responsible for training can select content in several ways: (1) create it from scratch, (2) consult with subject matter experts, (3) examine theory and research in the literature, (4) purchase off-the-shelf materials, and (5) contract with a training vendor to create the materials.38 No one way is best, and many training designers combine these techniques. For example, a management training course offered by Ford Motor Company includes materials created by the company's trainers in consultation with Ford engineers, materials taken from the published literature on management, and some off-the-shelf videos and exercises to help build managerial skills such as delegating and conducting performance reviews.

Because creating materials from scratch or in consultation with local experts is time consuming, many organizations use training vendors to create their training. Training vendors are companies whose primary business is to design and deliver training programs. To select a vendor that will provide a strategically relevant and high-quality program, management should ask prospective vendors a series of questions such as the following:39

Training vendors

Organizations that sell existing training programs or services to develop and deliver training programs.

- What projects have you completed that are similar to our project in terms of needs, objectives, and situation?

- May we see samples of your work? What evidence do you have that this work was effective? May we contact your references?

- Who will be working on this project, and what are their backgrounds and qualifications?

- Explain your work process. Where will you work? What will you need from us in terms of space, personnel, information, and other resources?

- Explain your evaluation process. How many milestones do you expect? How will you monitor progress? How would you prefer to receive feedback?

- What do you expect that this project, as explained up to this point, will cost? How do you charge? How are expenses handled?

- If we experience overruns in cost or time, how are those handled?

- Who will own the final work—our company, your company, or both?

TRAINING METHODS

The various ways of organizing content and encouraging trainees to learn are referred to as training methods. Training methods vary in terms of how active the learner is during training. More-passive methods can be useful, but they should seldom be used without the addition of at least one more-active method.

Training methods

How training content is organized and structured for the learner.

Presentation

Presentation is the primary passive method of instruction. A presentation involves providing content directly to learners in a noninteractive fashion. It is a passive method because learners do little other than read or listen and (hopefully) make sense of the material. The most common type of presentation is a lecture given by an instructor. Lectures have a bad reputation, but research suggests that people can and do learn from them.40 Lectures are an efficient way for many learners to receive the same content and gain the same knowledge. This means that presentations can be useful when the learning objective of training is for trainees to gain knowledge, such as an understanding of product features. A disadvantage of presentations is that learners are not given any formal opportunity to test or apply what they are learning. For this reason, presentations seldom help trainees gain skills.

Presentations can include various types of information. Some presentations include only verbal information (words), but others also include auditory information (sounds), static visual information (pictures), and dynamic visual information (animation). Presentations can be made more interesting with the addition of these other types of information, but the additional information should complement rather than distract from the verbal information being conveyed. Trainees can be overwhelmed or confused if confronted with too much information.41

Source: Adapted from Alan M. Saks and Robert R. Haccoun, Managing Performance through Training and Development, 3rd ed. (Ontario, Canada: Nelson, 2004), 162.

To avoid the problem of presenting too much information at once, companies may break training into several units. For example, to prepare its employees for the General Securities Representative Exam (Series 7), Merrill Lynch has a course that combines written text, telephone tutoring, and computer-aided testing. The written text is offered in a series of specially prepared booklets that present information in short paragraphs and use bold print for key concepts.42 Breaking down material in this way helps to ensure that trainees can learn without being overwhelmed.

Presentations can help employees learn even more if they are combined with active methods. You have probably experienced this in school. Listening to a lecture may help you learn a fact or two, but without an opportunity to do something with that knowledge, you forget it.

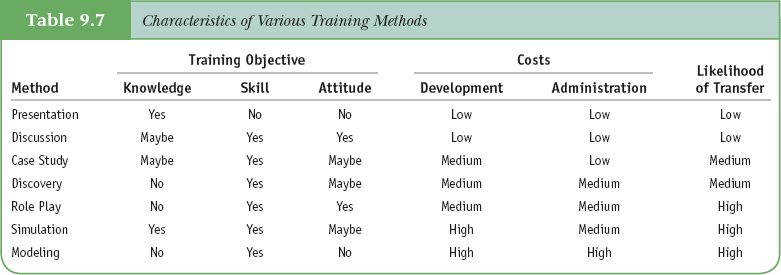

Table 9.7 contrasts presentation with other training methods in terms of what works best for particular objectives, as well as relative costs. Methods should be selected primarily based on their usefulness in helping achieve the training method's objectives. The table also indicates whether transfer of training is likely based simply on the nature of the method. These factors, along with preferences of the instructor and of trainees, should all be considered when selecting the training method for a particular program.43 Methods that directly increase transfer are discussed later in this section.

Discussions

Discussions represent a more-active training method. Discussions increase trainees' involvement by allowing two-way communication between trainer and trainees and among trainees. Discussion can help trainees to accomplish several things:

- Recognize what they do not know but should know.

- Get their questions answered.

- Get advice on matters of concern to them.

- Share ideas and develop a common perspective.

- Learn about one another as people.44

Discussions can be used to build knowledge and critical-thinking skills, but they are best used to help improve motivation and change attitudes. Discussions must be facilitated by a trainer in order to allow everyone an opportunity to participate. With larger audiences, discussions often do not work well because not everyone has a chance to contribute.

Case Study

Case analysis is an active training method in which trainees discuss, analyze, and solve problems based on real or hypothetical situations. Cases can be used to help teach basic principles and to improve motivation and change attitudes. Generally, however, the primary objective is to develop skill in analysis, communication, and problem solving.45 Cases vary in length and complexity. Although long, complex cases are often used in business schools, trainers in businesses shy away from them, preferring to use shorter cases.46

Discovery

Discovery is an active method that involves presenting trainees with a task that offers rich opportunities to learn new skills. For example, employees might be given access to a new computer program and asked to figure out for themselves how to do their work tasks using the program. Although this method may sound more like learning by experimentation than training, discovery can be structured so that skills needed for job performance are available to be learned. In effect, discovery is experimentation in a controlled training environment.

Discovery can be highly motivating for trainees, but it has serious drawbacks. Without any guidance from the instructor, it is highly inefficient and can result in people learning the wrong things.47 A more efficient approach is discovery coupled with guidance, where the instructor is more active in asking questions and providing hints that help learners while they explore. Appropriate guidance can help motivate trainees and ensure that they learn the best way to perform the task.48

Role Play

When trainees engage in role playing, each participant acts out a part in a simulated situation. This active method offers an opportunity for trainees to practice new skills in the training environment. It is most often used to help trainees acquire interpersonal and human relations skills. Role playing typically has three phases:49

- Development involves preparing and explaining the roles and the situation that will be used in role playing.

- Enactment involves the time that trainees take to become familiar with the details of the role and then act them out. Enactment can be done in small groups, with two actors and an observer, or with larger groups, with a small set of actors and the rest of the audience serving as observers. Of course, for skill building to occur, all trainees must have an opportunity to serve as an actor at some point.

- Debriefing, in which trainees discuss their experiences, is considered the most important phase of role playing. Discussions should address the connections among the role-playing experience, the desired learning outcomes, and the desired organizational outcomes. Trainers must provide feedback to ensure that trainees learn from the role-playing experience. In other words, trainers must offer constructive criticism to trainees, explaining what they did well and where they need more practice.

Simulation

Simulations are active methods that reproduce events, processes, and circumstances that occur in the trainee's job. Participating in a simulation gives trainees the opportunity to experience at least some aspects of their job in a safe and controlled environment and build skills relevant to those aspects of the job. For example, pilots can be trained with mechanical flight simulators. Simulations can also involve role playing with many actors or interactive computer technology, such as in a virtual world like Second Life. To achieve the greatest benefits, simulations should be designed to replicate as closely as possible both the physical and psychological conditions that exist on the job. For instance, to simulate a manager's daily experience, trainees could work on multiple tasks simultaneously and coordinate their efforts with those of other people in order to get their tasks completed.50 After all, these are the conditions under which managers typically accomplish their work. Related to simulations are educational games, which combine entertaining engagement with attention to user's learning. Computer games are becoming more popular, but they should be used with careful attention to selecting or designing a game that triggers learning of relevant information.51

Modeling

Behavior modeling is a powerful method that draws together principles of learning from many different areas. As described in the “How Do We Know?” feature, research has repeatedly found that this method is effective for improving skills.52 The basic process is simple:

- The trainer explains key learning points.

- The trainer or another model performs a task while trainees observe.

- Trainees practice performance while the trainer observes.

- The trainer provides feedback to the trainees.

Behavior modeling works particularly well when the model is someone whom the trainees see as credible and when that model shows both positive and negative examples of the task performance.53

On-the-Job Methods

With the methods discussed so far, trainees work off the job in a training setting. Training can also occur on the job. One common approach to on-the-job training is also among the least likely to help employees learn. Some companies pair up inexperienced employees with experienced employees and ask the inexperienced employees to watch and learn.54 This approach can be a useful way to help employees become familiar with the job, but it is not always effective because experienced employees may not do the work properly or may not know how to teach. In fact, because this type of on-the-job training is often poorly planned and ill structured, it seldom fits the definition of training provided at the start of this chapter.

Effective on-the-job training is structured and systematic. Structured on-the-job training is an application of behavior modeling that is carried out in small-group situations on the job. The process is the same as that described in the discussion of behavior modeling: the trainer explains key learning points and then performs the task while trainees observe. The trainees then practice performance while the trainer observes, and the trainer provides feedback.

TRAINING MEDIA

Training media are the means by which content and methods are delivered to trainees. Each passive and active training method we have discussed can be delivered in a number of different ways. For example, the information in a presentation can be transmitted by an instructor face to face (a classic lecture), an instructor via video or Web conference (videoconferencing), a sophisticated computer program, a basic computer presentation or website, an audio presentation (such as with an iPod or other MP3 player), or typed written material. The trend today is toward using some form of technology to deliver training. Indeed, this trend has been heralded as an e-learning revolution. e-Learning is training delivered online, and it has both benefits and drawbacks.

Training media

How training content and the associated methods are delivered to the learner.

e-learning

Training delivered through computers and network technology.

With all the possible choices, how can an organization decide which training media to use? There are no powerful research results suggesting that only one or two media work for delivering training. Instead, the choice should be guided by a two-step process. First, the selected training method should be examined to see if it has a media requirement. A media requirement is a characteristic of a training medium that is fundamentally necessary to ensure that a training method is effective. Second, the cost and accessibility of the remaining media should be considered to make the final selection. We next look more closely at each of these steps.

Media Requirements

You might wonder whether it is really possible to learn through all of the different media listed above. Occasionally, people ask, “Doesn't training have to be delivered face to face, by an experienced instructor, to be effective?” The answer is clearly no. As described in the “Technology in HR” feature, carefully designed training can be equally effective whether it is presented via technology (like computers or videoconferencing) or face to face by an instructor.55 In fact, some studies have shown that technology-delivered training can be more effective than traditional face-to-face instruction. Nevertheless, some training methods do require specific media characteristics.56 Two fundamental media requirements are explained here. Other requirements may arise in the course of developing a training program in a particular organization with a particular set of objectives and methods.

First, if the training uses guided discovery, role playing, simulations, or behavior modeling exercises, then an instructor or sophisticated computer program is required. To be effective, these methods require someone to analyze what the trainees do and provide feedback that helps them gain skills. Therefore, either an instructor must be present, or a computer must be programmed to behave like an instructor.

Second, if a training presentation includes both video and audio, then the training medium must be able to deliver both video and audio. Although somewhat obvious, this requirement suggests that teleconferences, which organizations use to deliver presentations to people scattered all over the country, and podcasts should only be used for presentations that are primarily verbal. If visual materials are an essential part of the presentation, then videoconferencing or some similar medium should be used. Web conferencing, which includes a window to display charts, graphs, video, and animation, has become popular for this type of presentation. A sample screenshot of just such a program is presented in Figure 9.5. This graphic includes a main window for the display of content, a list of participants in the upper right-hand corner, and a video of the presenter in the bottom right-hand corner.

Figure 9.5 Screenshot of a Web Conference. Source: Web-ex. Used with permission.

Cost and Accessibility

Different training media have different costs, and more technologically sophisticated media not only are more expensive but also may create access problems. For example, if you develop a CD-ROM–delivered computer training course, but it only runs on high-end PCs with Windows operating systems, then it's possible that not all employees will be able to use it. Employees who do not have high-end computers, or who work with Apple computers, may be unable to take training conveniently. Both cost and access should be taken into account when finalizing choices about media.

In general, if the audience for training is small, then the organization may choose to save time and money by using media that don't require time-consuming work up front. In such a case, a face-to-face live presentation may be preferable to computer-delivered training. However, if a company already has successful templates for creating computer-delivered training, then it may actually be less expensive than other delivery media.57

TRANSFER-ENHANCEMENT TECHNIQUES

As noted earlier, learning does not guarantee that trainees will transfer what they learn to their work back on the job. As a result, transfer will not necessarily happen even if training is designed and delivered in the ways we've just discussed. What can the organization do to foster transfer of training? A number of techniques that can be used before, during, and after training will help.58

Before Training

One of the least commonly used but most powerful techniques to enhance transfer, at least according to trainees, is management involvement with trainees prior to training.59 Managers can work with employees in a number of ways to help them prepare for training. For example, managers can build transfer into employees' performance standards, offer rewards to trainees who demonstrate transfer, involve employees in planning training, brief trainees on the importance of training, send co-workers to training together, and encourage trainees to attend and actively participate in all training sessions. When managers work in partnership with trainers and trainees, transfer is much more likely to occur.

One highly structured way for managers to work with employees is through a behavioral contract, which spells out what both the employees and the managers expect to happen during and after training. A behavioral contract would include specific statements about how the employee will use newly acquired knowledge and skill on the job and how the supervisor will support those efforts. The best approach is for employees to work with their managers to create and sign a contract that both agree on.60 Because it is so formal, the behavioral contract may not be appropriate in all organizations. In organizations whose policies and practices are generally more informal, a simple conversation between manager and employee may be more appropriate. A sample behavioral contract is shown in Figure 9.6.

Behavioral contract

An agreement that specifies what the trainee and his or her manager will do to ensure training is effective.

Figure 9.6 Sample Behavior Contract Between Trainee and Manager. Source: Information from Mary L. Broad and John W. Newstrom, Transfer of Training: Action-Packed Strategies to Ensure High Payoff from Training Investments (Reading, MA: Perseus, 1992).

During Training

During training, the trainer can use at least two different approaches to foster transfer. The first approach is to structure the training in ways that will help trainees to generalize what they learn to situations back on the job. This can be done by focusing training on general principles and varying the situations under which skills are practiced.61 For example, training managers to conduct performance reviews should provide general guidelines rather than a lock-step process that must be followed every time. General rules provide knowledge that is flexible enough to be applied in a variety of situations. The management trainees can then practice conducting performance reviews in a number of different role-playing situations with characters who react differently. Practice of this type will better prepare them for the uncertainty and variability of the task when it is done back on the job.

Relapse prevention training

A transfer enhancement activity that helps prepare trainees to overcome obstacles to using trained behaviors on the job.

The second approach uses an instructional add-on called relapse prevention training. This training directly addresses situations in which trainees may have difficulty applying trained skills and provides strategies for overcoming relapses into old patterns of behavior. Relapse prevention programs generally ask trainees to do the following: (1) select a skill from training and set a specific goal to use that skill, (2) anticipate when they might relapse to old behavior instead of using the newly acquired skill, (3) write out the positive and negative consequences of using (or not using) the new skill, (4) review relapse prevention strategies that can be used to prevent or recover from relapses, including recognizing behaviors that might lead to relapse and preparing a support network, (5) describe a few work situations that might contribute to a relapse, and (6) prepare strategies for dealing with these situations. Research has found that relapse prevention programs can be beneficial if the transfer-of-training climate is poor.62 A downside of relapse prevention is that it requires extra training time.

After Training

After training, the manager and trainee should work together to ensure transfer. Techniques managers can use include giving positive reinforcement for using trained skills, arranging for practice sessions, supporting trainee reunions, and publicizing successes in the use of trained skills. Managers might also consider reducing job pressures in the first few days that trainees are back from training, to allow the trainees time to test out their new knowledge and skill.

One other important action that managers must take is to provide trainees with an opportunity to use the skills from training as soon as possible after the training is over. This concept, known as opportunity to perform, is essential because without an opportunity to use the new knowledge or skill, it will decay.63 As you have probably learned in your own lives, knowledge or skill gained and not used is lost over time. For example, you may have memorized the capitals of all the states when you were in elementary school, but you probably don't remember many of them today. If there will be a time delay between when training must be done and when employees need to use it, managers must create opportunities for employees to refresh their knowledge and skill so it is not lost.

Opportunity to perform

Allowing employees a chance to use the skills they learned in training back on the job.

In the “How Do We Know” feature, you can learn about two interventions completed after training that helped boost transfer for restaurant managers.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

When objectives, content, methods, media, and transfer enhancements have all been selected, then training materials must be prepared, reviewed for accuracy and quality, and produced. What training materials will be needed depends on the choices made during design. For example, a course that is instructor-led will require trainees' guides, an instructor's guide, and perhaps audiovisual presentation material.

Effective training can take a long time to develop. It might, for example, take 30 to 80 hours of an HR professional's time to produce one hour of instructor-led training, including the time to conduct a needs assessment, draft a preliminary design, and obtain expert reviews of content. Producing technology-delivered instruction, simulations, and behavior modeling methods can be particularly time consuming. For instance, producing one hour of high-quality computer-delivered simulation may take as many as 400 hours of an HR professional's and a computer programmer's time.64 Of course, development times vary depending on many factors. The point is that it can take a considerable amount of time to make decisions about training and then act on these decisions to produce the necessary training materials. HR professionals must therefore be effective project managers, taking care to leave enough time to both design and develop all necessary materials.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 5

How Do Organizations Determine Whether Training Is Effective?

Training evaluation is the process used to determine the effectiveness of training programs. Training effectiveness refers to the extent to which trainees (and their organization) benefit as intended from training. The training evaluation process typically involves four steps: (1) determining the purpose of the evaluation, (2) deciding on relevant outcomes, (3) choosing an evaluation design, and (4) collecting and analyzing the data and reporting the results.65

Training effectiveness

The extent to which trainees and their organizations benefit as intended from training.

PURPOSE

The first step in evaluation is to determine the purpose of the evaluation. Most of the reasons to evaluate training fit into three primary categories: (1) provide feedback to designers and trainers that helps improve the training, (2) provide input for decisions about whether to continue or discontinue the training, and (3) provide information that can be used to market the training program.66

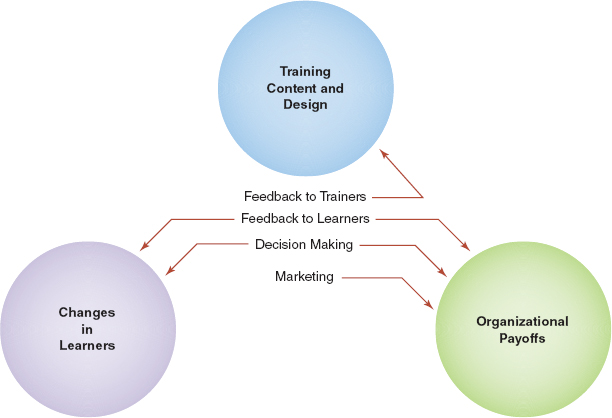

There are three primary targets of evaluation—that is, three kinds of information that evaluators can collect and analyze: (1) training content and design, which can be assessed to provide feedback to designers and trainers; (2) changes in learners, which can be measured to provide feedback and make decisions about training; and (3) organizational payoffs, which can be collected and used for all three purposes.67 Each target can be assessed in a number of ways, as discussed in the next section. Figure 9.7 illustrates this perspective on training evaluation.

To provide an example of the connection between purpose and targets, consider a company that offers new supervisors a one-week, face-to-face training course in basic supervisory skills. This training might be evaluated for one, two, or three different reasons. If the training were evaluated to provide feedback that would improve the course in the future, then training experts could be asked to review the training to ensure that the content is accurate and the design choices (methods and media) are appropriate. If the training were evaluated to determine whether it should be continued in the future, then learners could be observed to see if they actually learned the material and used it on the job. Finally, if the training were evaluated to develop marketing materials that would help recruit future trainees, then changes in new supervisor turnover for business units that use the training could be tracked. If turnover rates were lower in business units that used the training, then this result could be crafted into a powerful story about the benefits of training. The story could be distributed widely to encourage other business units to send their supervisors to the training. Of course, an organization might evaluate this training course for all three reasons, in which case it could do all of the above!

Figure 9.7 The Three Primary Targets of Evaluation. Source: Kurt Kraiger, “Decision-Based Evaluation,” in Kurt Kraiger (ed.), Creating, Implementing, and Managing Effective Training and Development (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002), 331–376. Used with permission.

Evaluation is not always a single-step activity that only occurs at the end of training. In fact, evaluation efforts may begin while training is being designed. Evaluators may collect information about whether the training objectives and content are aligned with the business strategy and whether the training methods are aligned with the training objectives. This effort might include review by subject matter experts and managers, as well as feedback from trainees following exposure to a course outline or sample materials. Doing evaluation work while training is being developed helps ensure that training is likely to have the desired effects.68

OUTCOMES

Training outcomes can be roughly divided into four categories—reactions, learning, transfer, and organizational results.69 These outcomes provide different types of information about training that are more or less useful, depending on the purpose of the evaluation.

Reactions

Trainee reactions capture how the trainees felt about training: Did they like it? Did they think it was interesting and useful? Reaction measures are similar to the end-of-semester teacher evaluation forms that most colleges have students complete. Evaluations of this sort can be useful for determining how learners react to the training content and design, but they are not good measures of learning. Research shows that reactions do not always relate to how much trainees actually learned.70 Still, reactions can help evaluators gauge what went well and what did not, which can be useful for providing feedback to training designers and trainers. Reactions can also be useful as overall measures of satisfaction with training courses. High levels of dissatisfaction suggest that something is wrong and that trainers may need to alter the program in some way.

Companies should be careful about making decisions to discontinue courses or to fire trainers based on reaction data alone. Research suggests that there are many determinants of reactions, including factors that are not under the trainer's control. For example, trainees' general tendency to be positive or negative can sway their reactions.71 If a trainer happens to get a particularly negative set of trainees, then reactions to that course may be lower regardless of what the trainer does. In sum, reaction data should be interpreted cautiously and are probably better used to provide feedback to improve training than to make decisions about discontinuing training.

Learning

As noted earlier, learning is a change that occurs from experience. Learning can involve knowledge, skills, or attitudes, and each of these can be assessed.72 Knowledge can be assessed with traditional tests, such as multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blank, or open-ended tests. It can also be measured with other techniques, such as asking trainees to explain relationships among key concepts and testing whether trainees' beliefs about relationships are similar to experts' beliefs. Skills can be measured by scoring role plays, simulations, and behavior-modeling exercises for the use of the desired skills. Attitudes can be assessed by asking trainees about their beliefs and their motivation, as well as by watching trainees' behavior for evidence of the desired attitude. If an objective of training is to have employees believe that promptness is important to customers, for example, then trainees could be scored for their promptness in end-of-training activities.

Learning objectives for a training program should be easily classifiable into these categories and should make clear how to evaluate whether learning has occurred. For example, the learning objective in Table 9.6 concerning wine varieties offers a precise way to determine if a waiter has learned as intended from a wine course. The revised objective was “Given three glasses of different varieties of red wine, be able to identify each correctly while blindfolded.” Because this objective was written so effectively, it provides everything necessary to determine whether the training was effective. All that we need is some wine, some glasses, and a blindfold.

Transfer

Transfer, as we have seen, refers to applying learning acquired in training to behavior on the job. To assess transfer, evaluators can ask employees about their own post-training behavior, or they can ask trainees' peers and managers about the trainees' behavior. In some cases, existing records can be used to examine transfer. For example, if sales training encourages trainees to sell items with both high and low profit margins, the records of employees' sales can indicate whether their actual sales move in that direction.

Organizational Results

Organizational results are, of course, outcomes that accrue to a group or the organization as a whole. To assess organizational results, we can use basic measures of effectiveness, such as an increase in sales for the whole company or a decrease in turnover, or we can use efficiency measures, which balance benefits with costs.