Successful Implementation

Abstract

This chapter identifies the main stages in successfully implementing an automation project after the specification and justification processes are complete. We review the selection of vendors, as well as the planning and execution of the project. To this end, we discuss the benefits of involving staff and vendors in the various stages of a project. The chapter also includes a review of common problems and how these might be avoided.

The successful implementation of an automation project requires a project manager who possesses the skills and techniques needed for any capital investment project. An automation project does require a team with automation knowledge and expertise, but the project manager does not necessarily have to have this skill set. Instead, with the necessary technical support, the project manager can provide planning, budget control, and more general project management functions.

The development of an automation project generally follows an iterative process. As described in Chapter 5, this process commences with the definition of the operations to be automated and the development of the initial concepts. These are then evaluated to determine both risk and cost, with the concept being refined until the optimum solution is derived. Once the concept has been finalised, the budget can be determined, the financial justification developed (see Chapter 7), and the project submitted for approval. Once the project is approved, a detailed specification can be created (see Chapter 6). This specification may be based on work already conducted, but it is important to commit the concept and requirements to paper to provide an expectation against which potential vendors are able to quote.

The project is now real and enters the implementation phase. The main steps in the implementation are vendor selection, system build and buy-off, installation, commissioning, and ongoing production. These are detailed below, together with guidance on project planning, staff and vendor involvement, and the avoidance of problems that can occur during the implementation.

8.1 Project Planning

The first important step is to develop a project plan. The specification may have defined outline timing, indicating the planned order date and the required date for start of production (SOP). However, it is important to develop a much more detailed timing plan covering all aspects of the implementation, including both external vendors and internal resources.

The first important issue is to review the delivery dates proposed by the bidding vendors to determine if these are within the initial timing provided in the specification. If they are all within the requested period, then it is safe to proceed using the original timing. If one or more are outside the period, discussions should be held with the relevant vendors to identify the reasons behind their proposed timescale. The vendors may have resource issues due to existing workload, or they may have items on long lead times within their proposals. Yet, they may also have provided a more realistic delivery schedule than those who are claiming to be able to achieve the requested date. Those vendors who claim to be able to achieve the required date should also be questioned to ensure the issues identified by the longer lead-time vendors are not applicable to the shorter lead-time vendors. If the investigation determines that the original date is a risk, then it may be better to delay the installation. There should also be some contingency built into the timing plan, partly for unforeseen items but also to accommodate project stages that might cause delays. This might include the time required for design approval (see below). It is better to ensure that the expectations of the senior management regarding delivery and SOP are realistic rather than missing the planned dates in the future.

Having finalised the delivery date, the project manager should take note of the lead times quoted by the vendors in respect to the anticipated order date. Internal knowledge of the vendor selection requirements and order sign-off process, in particular the likely time required, should be considered to ensure an order can be realistically placed within the timescale requested by the vendors. This again may cause the project manager to reconsider the delivery date.

The overall project timing plan can then be developed commencing from the current position. This should therefore include time to assess the quotations and expertise of the potential vendors. If necessary, the project manager should allow time to visit existing customers of those vendors, conducting detailed discussions with a number of vendors to ensure that the specification is fully met by their quotations. A date for the selection of the vendor can therefore be identified. The vendor selection is followed by a period to allow for the generation and sign-off of the order. This period should include time for discussions over terms and conditions and the finalisation of the scope of supply and pricing. The date for order placement can then be specified.

From here, the project manager can use the vendor’s lead time to identify the time required before delivery. The lead time may include a number of phases such as design, manufacture, system assembly, and proving, prior to the factory acceptance tests (FAT) conducted on the vendor’s premises. It may be worthwhile to identify these stages, particularly if input is required by the customer at any stage. For example, this might include design approval and parts for programme development and the performance of the FAT. In defining this element of the timing plan, the project manager should include any delays that may be caused by the customer (e.g. the time required to provide design approval).

There is normally a need for a number of project meetings during any project. The number and frequency of the meetings will be dependent on the size and complexity of the project. As a guide, it is often worthwhile to plan for monthly meetings at the start, even if these scheduled meetings are required to change later, due to the specific circumstances at the time. The dates of these meetings can be included on the plan. This stage of the project is concluded by the FAT, after which delivery takes place.

Following delivery, the project manager should identify a period for installation and commissioning. This is followed by the site acceptance test (SAT). Production start then follows the SAT. The team might also benefit from allowing a further period for production ramp-up. This is to provide a period during which the workforce is able to gain experience of the new automation solution with the objective of achieving full production at the end of this period. If the automation system is simple, the ramp-up period may be less than one day, but if it is a complex system that requires significant learning by the operators and maintenance staff, a few weeks may be appropriate.

The team needs customer resources and products during these stages, and this need should be identified on the plan to ensure other departments can be made aware of what will be required and when it will be needed. Training may also be required, possibly including operator training, robot programming training, and maintenance training. The timing of each of these packages and the manpower to be allocated should be included on the plan to ensure the necessary resources can be made available as required.

The basic timing plan developed above forms the initial plan for the project. This includes the major milestones, such as order placement, the project kick-off meeting, design approval, FAT, delivery, SAT and the SOP. If at all possible, the plan should also include a contingency in the event of any unforeseen delays. The challenge is to ensure the SOP is both realistic and meets the needs of the business.

Once the vendor has been given their order, the project manager often requests a detailed timing plan from the vendor at the project kick-off meeting. This more detailed plan can then be compared with the initial plan, and the team can make any adjustments needed to provide a final timing plan for the project. This final plan should then be used to monitor the progress of the project and to highlight any changes to timing, giving the team the ability to assess the implications of those changes.

8.2 Vendor Selection

The initial key step in the selection of vendors is to provide a specification (see Chapter 6) against which vendors must quote. This also provides a common basis against which the various quotations can be assessed, and it can be used to ensure that all the vendors are quoting to deliver equipment and services intended to achieve the same objective. The actual equipment and services may be different between each vendor because they may not all be quoting the same concept.

Normally, the project manager approaches a number of vendors for quotations. The optimum number is probably three, because this number ensures that the workload required to discuss the project and assess the responses of those vendors is not too time consuming. The project team must perform some initial work to identify the vendors to whom the customer will send the request for quotation, because the invited firms must have the necessary expertise and resources for the project. There is little value in investing time and effort in working with a potential vendor, if that firm either does not quote or falls short in the vendor assessment at an early stage (see below). The vendors also invest time and resources into the development of their proposals, and therefore, only vendors who have a reasonable chance of success should be requested to quote.

Having received the quotations, the project team must then perform a comparison of the proposals and the experience and expertise of the vendors. A first step is to review the proposals to ensure they have covered all the elements of the specification. The vendors may have listed exclusions or exceptions to the specification, and further investigation of these may be appropriate in order to determine the reasons for the exclusion and also implications for the customer. A careful review of the quotations may also lead to the identification of items that require clarification. One or more vendors may have identified issues or points which are not apparent with the other vendors. One or more vendors may have also proposed an unusual concept that requires more detailed investigation to determine if it is appropriate.

It is therefore worthwhile to hold a review meeting with each of the vendors to work through their proposals step by step to ensure the entire specification is covered or justifiable reasons and appropriate alternatives are in place for those items not covered. It is not ethical to share the ideas of one vendor with the others, and therefore, the discussions with each vendor should be treated as confidential.

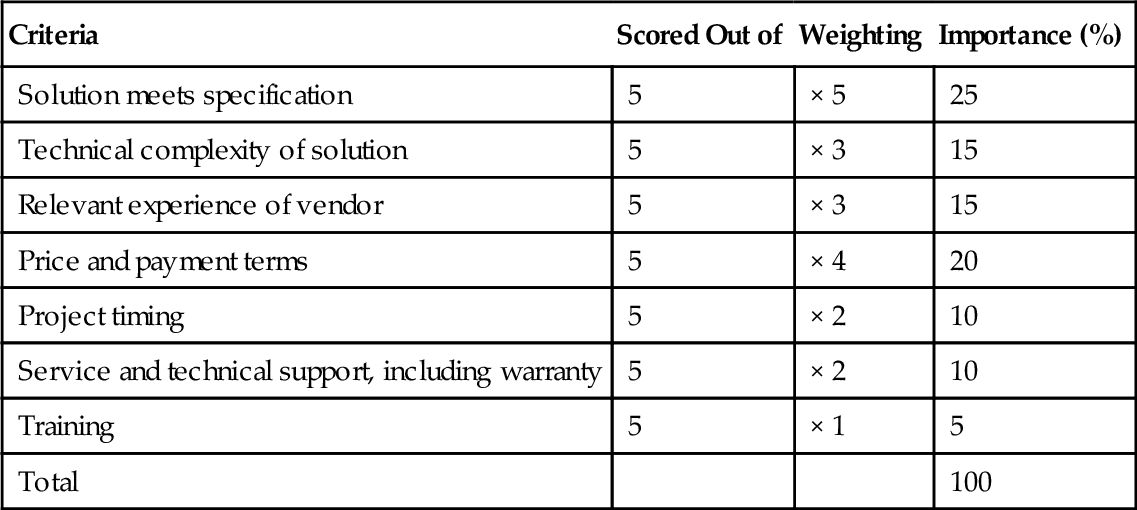

Having held these meetings, the project team should understand how each of the vendors stands versus the specification, and a valid comparison can then be made. To assist with this assessment, the team may develop a table of key items against which the vendors can be scored. These key items can also be weighted to ensure that their relative importance is reflected in the assessment. An example of such an assessment is provided in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1

Proposal and Vendor Assessment

| Criteria | Scored Out of | Weighting | Importance (%) |

| Solution meets specification | 5 | × 5 | 25 |

| Technical complexity of solution | 5 | × 3 | 15 |

| Relevant experience of vendor | 5 | × 3 | 15 |

| Price and payment terms | 5 | × 4 | 20 |

| Project timing | 5 | × 2 | 10 |

| Service and technical support, including warranty | 5 | × 2 | 10 |

| Training | 5 | × 1 | 5 |

| Total | 100 |

An equally important element of the vendor selection is an assessment of the vendors’ experience and expertise. If a vendor has experience of a very similar installation or has very relevant expertise, that firm has knowledge that will both assist with the project and also reduce the risk. The vendor will also be quoting from a more knowledgeable position than vendors without the experience, and therefore, the experienced firm’s quotation is likely to include any lessons learnt from previous projects. This experience or expertise should also be included in the overall assessment discussed above, and it may be given the same importance as the price to ensure the risk of choosing a less experienced vendor is correctly factored into the assessment.

The ability of the vendor to provide service support may also be important. For example, if the system is going to be critical to the production operations of the customer and will be operating over three shifts, the ability to provide 24-hour service support with guaranteed response times may be a key issue. This type of capability is often only available via the larger vendors, because the smaller vendors do not have the necessary resources. The self-sufficiency of the customer and the need for service support from the vendor could therefore be key requirements.

Finally, the size and financial stability of the potential vendors may be considered. These factors become more important for larger projects for which the ability of the vendor to fund the cash flow through a project can be an issue. The longer term viability of the vendors is also important because the customer wants the vendor to be available to resolve future problems with the system and to possibly provide for upgrades or reconfiguration if required. Therefore, the project team must assess the longer-term prospects for any vendor being considered for a project.

Once the assessment has been completed, the results may indicate an obvious choice for the project. This could be one vendor that meets all the criteria and also achieves the best score on the comparison. If there is more than one remaining candidate, further discussions with the most appropriate vendors may be required to finalise the choice. These discussions may involve negotiations on price. If the customer’s purchasing department is involved, price negotiation is normal. It is better not to push too hard to achieve price reductions because this could impact the project. Every vendor aims to achieve a profit, and it is important for the customer that the vendors do achieve this profit. Without a profit, many vendors try to adjust the scope of supply or the quality of the equipment selected to ensure they can recover their planned profit position. If the project produces a loss for the vendor, this could also affect their longer-term viability. Therefore, price negotiations should be conducted to ensure that the best deal for the customer, while also taking into account the implications of any price reductions that are achieved.

It is often a false economy to select the vendor with the lowest price, particularly if the above assessment is not undertaken. This vendor could have made errors within their cost estimates or have underestimated the resources required to execute the project, which would then lead to a lower sell price. As the project is executed, the vendor will realise the error, and, given that no companies are in business to make losses, the vendor will then try to recover the situation, which can only lead to problems within the project. If the lowest price vendor meets all the necessary criteria, but there are still concerns, it is valid to add a contingency to cover the risks. If they are still the best choice, then the order can be placed with them, but the addition of this contingency may then make other vendors more attractive.

An approach taken by some customers is to request five quotations. The lowest price quote is then rejected because the vendor is likely to have made an error or underestimated the scope. The highest price quote is also rejected because the vendor either does not want the business, possibly because they are already busy, or they may have provided an inappropriate solution. The discussions then proceed with the three vendors who provided pricing in the middle of the range.

In some cases, a customer may only ask one vendor to provide a quotation. This is due to the previous experience of that vendor and satisfaction with their previous work. This single-sourcing approach often saves time for both the customer and the vendor. If the current project is similar to previous projects, these can be used as a guide when assessing the price that is being quoted. However, if the project is a new application, it can be difficult to assess whether that vendor is providing value for money, because there is little information on which to base the assessment. Single sourcing can lead to the development of a long and mutually beneficial relationship between vendor and customer. The vendor is able to enter into more detailed conversations early in the process, and they actually form part of the team that develops the concept and the project. However, it is best to check the market occasionally to ensure the customer is receiving value for money.

Having selected a vendor, the customer can place the order. This should reference the important documents related to the project, including the specification (URS), the vendor’s proposal and any other documents passed between the parties that detail clarifications to these documents. The required delivery date should be clearly stated, as should the terms and conditions against which the order is placed.

8.3 System Build and Buy-Off

Having placed the order, the customer’s project manager first holds a kick-off meeting between the customer’s project team and the vendor’s project team. This meeting is normally organised between the respective project managers. The purpose of the kick-off meeting is to review the entire project, covering the operations to be performed within the system, the products to be processed, the scope of supply, and the project timing, in order to ensure there are no misunderstandings between the vendor and the customer. It is worth noting that the vendor’s project team is often composed of different personnel than those involved in the sale, and it is in the customer’s interest to ensure all aspects of the project are fully understood and agreed upon.

This meeting should be recorded in minutes agreed upon by both parties to avoid any misunderstanding that may become apparent later. In addition, the vendor should also produce a detailed timing plan very shortly after this meeting to ensure any variance to the planned timing is apparent to the customer. This timing plan should include all the milestones (see Section 8.1), and it becomes the document against which the progress of the project is assessed.

In most projects a design phase follows. This phase covers the detail design of all the elements of the system and the final design of the overall system. Simulation is often a valuable means for providing confidence that the tools, such as welding torches or grippers, can access the parts as intended and also that the system performs to the planned cycle time. The simulation can build on work already performed in the concept development phase (see Section 5.4). Once the designs are completed, they should be submitted to the customer for approval. The customer should check the designs to ensure that they are appropriate for their use and meet the relevant standards. The customer should also verify that the design of the system will fit within the factory space allocated and the operation of the cell, including access for maintenance, is suitable for their production environment, providing a workable solution.

It may be appropriate to conduct various assessments of the design at this stage, particularly on more complex systems or applications. These assessments could include a failure mode effects analysis (FMEA) on both the process and the equipment. The purpose of these studies is to identify potential causes of failure, as well as the likely frequency and seriousness of that failure. The studies should be conducted jointly between the vendor and customer, and they should include not only aspects of the system itself but also the impact of input part variability as well as other issues external to the system that could affect system performance. The output from the studies is assessed, and, for those issues considered to be important, the teams define actions and identify responsibilities to provide solutions to these potential problems.

Similarly, for complex or large systems, it may also be worthwhile to undertake a repair and maintenance review. The purpose of this is to identify the potential equipment failures within the system and the processes required to conduct the repair and maintenance necessary to ensure the system continues to operate effectively. This may lead to design changes so that repairs can be conducted quickly, minimising downtime.

Having completed the design and achieved customer approval, the vendor then sources the equipment and commences manufacture of the elements of the cell. In many cases, the system is built on the vendor’s premises and fully programmed to enable the FAT to be performed. The customer should visit the vendor’s site on a regular basis to view the progress of the work and assess this against the timing plan.

As the project build is approaching completion, the customer must provide parts for the robot programme development, testing, and FAT. These should be truly representative of the actual parts to be processed in production. This can sometimes be difficult to achieve, particularly for new products. In such a case, the customer and vendor must reach a mutual agreement as to how any variances are to be accommodated or assessed.

The FAT is an important milestone. There is often pressure at this stage to ship and install the system because the project is running close to the plan or is actually late. If the system fails the FAT, it is much easier, and less costly, for the vendor to fix problems at its own site. It is also preferable for the customer to delay shipment until the system is proven, because any issues on the customer site can reduce the credibility of the system, which will cause problems in production later. It is therefore better for both parties to ensure the FAT is achieved successfully even if this requires a delayed installation.

8.4 Installation and Commissioning

The customer should plan the delivery and installation, with advice provided by the vendor. It may be necessary to decommission and remove existing equipment from the area or to move existing facilities to provide access to the area within the factory where the automation system is to be sited. If an area of production is to be out of operation for a period, it may be necessary to build additional product in advance to ensure production can continue within other areas of the factory. At an early stage in the project, the vendor should have visited the customer site to review the area for the installation and access to the site, and the vendor and customer must devise a joint plan to carry out this work.

If the delivery takes place during production, other operations may be disrupted, and therefore, the production staff need to be made aware of what is required and when this will take place. To avoid this, delivery can take place outside of production hours, either during planned shutdowns or over weekends. It is also important that the customer provides the necessary lifting equipment, such as forklift trucks, unless this forms part of the contract with the vendor. The customer is normally responsible for providing the services, electrical, compressed air and water, if required, to an agreed point within the area of the installation. This work should be completed prior to installation taking place.

There should be a clear definition of work to be conducted by the customer and work to be conducted by the vendor. Related to this division of labour, the customer should ensure the vendor is aware of any supervision or safety issues related to the tasks to be performed. For example, any cutting or welding may require the presence of the site fireman. It may also be necessary for the vendor’s staff and subcontractors to undertake a site safety course prior to working on the customer’s site, which should be planned in advance.

If possible, the project can often benefit from the customer allocating one or more engineers to assist with the installation, particularly in terms of liaising with local staff to resolve any questions or issues raised by the vendor. These engineers also have the opportunity to be more involved and gain knowledge of the system during this phase, which could be beneficial when the vendor has completed the work and left the site.

Once the installation and commissioning are complete, the SAT is undertaken. This may require an interface to be made between the new automation system and current production, both upstream and downstream. This may cause some issues with production. It is therefore beneficial to review the requirements and tests to be undertaken within the SAT with the relevant production staff.

On successful completion of the SAT, the vendor hands the system over to the customer, and the vendor’s staff normally leaves site. The operation of the system is now the responsibility of the customer. In some cases, standby cover is provided to assist with this handover. The need for standby cover depends on the complexity of the system and the existing customer expertise. The purpose of standby is not to operate the system but to provide assistance and guidance in the operation and maintenance of the system for the new operators and maintenance personnel. Therefore, standby is a backup.

During the commissioning period, the vendor normally provides training in the operation and maintenance of the system. This may be prior to the SAT, but it could also be afterwards, once the system is in operation. It is important that the customer and vendor agree on the extent of the training and the numbers of personnel to be trained. This is particularly true if there are multiple shifts to be trained. It is important that the appropriate personnel on each shift have the training necessary to correctly operate and maintain the system.

Documentation is important and should be provided as early as possible to the customer following the SAT. However, the documentation often cannot be finalised until the SAT is completed, in case any further required changes lead to modifications to the documentation. It may be beneficial for the customer to have an incomplete version of the documentation prior to the SAT, partly to enable checking of the information contained, but also to provide some backup once the vendor’s staff leaves the site. The final version of the documentation should then be provided promptly once the project is completed.

8.5 Operation and Maintenance

Once the system has been handed over and all of the vendor’s staff has left the site, the operation of the system is the sole responsibility of the customer. It is important that the system is operated as intended, and the parts provided to the system must meet the standards specified at the start of the project. In addition, if maintenance is required, such as changing consumable items, then this should be performed at the appropriate frequency using procedures detailed in the documentation.

Even if the system is well-built and fully proven, problems can still arise at this point. These problems are normally due to the inexperience of the customer’s operators and engineers who are unable to operate the system as well as the vendor’s staff. The problems can lead to the customer requesting support from the vendor because of perceived problems with the system. This situation can often cause conflict, partly because the vendor believes it has completed the work as required and partly because the vendor’s staff previously involved in the project may well already be committed to other work.

The provision of the final documentation package can also prove to be a problem because the engineers concerned are often required for other projects. The finalisation of the documentation can therefore become a lower priority, but it is important this is completed quickly. The project is not fully delivered until the documentation package is completed and accepted by the customer.

In most cases once the system is operating as planned, the customer does not consider any changes until a new product or product redesign is to be introduced to the system. However, it may be possible to increase the throughput of the system to gain further capacity. During the project, the vendor sets and achieves a target cycle time. Once the target is achieved, the vendor does not do any further work to improve the output. Over time the customer’s staff will have the opportunity to view and assess the operation of the equipment. If they have had the necessary training and are given the opportunity, they may be able to improve the operation of the system. Major changes involving further investment are not normally considered unless a very significant and justifiable improvement can be made. The ad hoc improvements are more likely to be software changes, as with the robot programme, or simple modifications to elements of the system that can be achieved in-house or for very little cost. The gain of production capacity may not be immediately important, but it may well provide benefits in the future and is therefore worthwhile.

The maintenance and service support for the system must also be considered. Normally, the vendor provides a 1-year warranty, but in some cases, the warranty may be 2 or 3 years. Although the vendor will fix problems within the warranty period, this does not necessarily guarantee a quick response to breakdowns. The type and level of support required depend on the expertise of and the training provided to the in-house maintenance staff. If the system is critical to the production of the customer, then a service response package may be necessary, possibly including 24-hour support and guaranteed call-out response times (see Section 6.2.14). This may be appear to be expensive, but compared with the problems it is designed to solve, it could be a worthwhile investment. Even if emergency cover is not required, the customer may want to consider an annual maintenance contract to cover any specific maintenance required, as well as a check of the system. These considerations very much depend on the experience and expertise in-house. If the customer already has a number of robot systems, the operation may be able to handle most of the maintenance and service requirements on its own.

8.6 Staff and Vendor Involvement

In most cases it is better to involve staff in projects to gain the benefit of their knowledge and experience, and a number of different groups can make significant contributions to the success of a project. The main obstacle to early involvement is the need to address the insecurity that the introduction of a robot system can raise, particularly in relation to the job prospects of the production staff. If the system is for new work, then it is unlikely that any staff will be displaced, but they may see the introduction of a robot as a threat to their futures. If the system is to take over existing operations, the workers who are performing those operations obviously see the robot system as a threat to their livelihoods. It is important that the rationale for introducing automation is clearly explained to the workforce and the impact on roles and specific jobs is addressed. The management must clearly state whether the affected staff are to be retrained to operate the robots or are to be moved to other jobs within the factory. Whatever the message and however it is delivered, all the parties involved in the automation project must be fully supportive. These parties can make the whole project easier and more likely to achieve success, or they can cause problems, more from lack of interest, cooperation or involvement in the project than from direct obstruction.

8.6.1 Vendors

If a new product is under design and the intention is to utilise automation for the manufacture of that product, the customer can benefit from involving vendors in the design phase. The vendors are able to provide advice on the ease with which the manufacture can be automated, and they may suggest design changes that can significantly aid the automation. If these changes are proposed early in the design stage, it may be possible to implement the changes at little or no cost. This may make the difference between a product that can be manufactured automatically and one that cannot be automated within a cost-effective solution. Even if the design is finalised, or outside the responsibility of the customer, the customer should discuss the design with the vendor. The vendor may be able to suggest small modifications that may be feasible and could have a major impact on the ease of automating.

8.6.2 Production Staff

The involvement of production staff can be very important for an automation project. It is therefore worthwhile to gain their full support and participation as early as possible. If automating an existing operation, the project team should involve the relevant staff at the concept stage. These staff members are performing the operations, and they understand the difficulties within the operations, the variability of the incoming parts, and the true operations that are performed, including any workarounds that have been developed. This type of information is often not detailed on the production instruction sheets, and it may not be known by the production management or the engineering teams. However, without this knowledge of the real situation, an automation project can face difficulties or even fail. Even if the project team is considering an application for new products and operations, the existing production staff may be able to provide valuable input based on its knowledge and experience of current production. The involvement of the production staff can therefore provide very valuable input to the concept design and also the development of the specification.

Continuing the involvement of the production staff throughout the project can also be worthwhile. Production workers do not necessarily have to attend all meetings, but the team should keep them abreast of progress. If, during the design phase, FMEAs are undertaken, the production staff may provide useful input. The FAT at the vendor’s premises is also a good opportunity to introduce the operators to the system, enhancing their confidence with the automation. Once the delivery and installation commence, these operators can be part of the installation team providing assistance to the vendor. This increases their familiarity with the equipment and, if this is building on involvement from an early stage, it should also encourage ownership of the system. This ownership can be the key to a successful system. If the operators want the system to work, they try everything they can to ensure that the system does work. Conversely, if they do not feel part of the project and do not have any ownership of the system, they do not actively support resolution of any problems, instead waiting for others to address any issues. The ownership really comes down to a question of attitude: do the operators want the system to work or not? This may be very important because they can be a key element in determining the success of a project.

It is also important to provide training to the production staff at an appropriate stage in the project. The training on the actual system may take place at either the vendor’s or customer’s site. Investing in more detailed training (e.g. in robot programming) may also enhance the operators’ capabilities and status, encouraging their support for the project.

8.6.3 Maintenance Staff

The maintenance staff can provide valuable input during the development of the specification. These staff members have experience with various items of equipment from different vendors already in use within the facility. They can therefore provide details about the most reliable equipment and the vendors who provide good service for breakdowns, maintenance, and spare parts. This knowledge can be distilled into a preferred vendors list to be included in the specification (see Chapter 6).

The maintenance staff can also be involved in reviewing the concept to gain an understanding of how they would access the system for repairs, offering their input as to the feasibility of the proposed solution from a maintenance viewpoint. Likewise, the maintenance staff can provide useful input to the review of the proposals provided by the various suppliers. Also, if repair and maintenance studies are conducted during the design phase of the project, the maintenance staff can provide useful information.

The maintenance staff should receive training on the system, which is likely to take place at the customer’s site. It may be beneficial to involve these staff in the installation and commissioning of the system, in support of the vendors staff, to enhance their capabilities. It may also be necessary to provide specific maintenance training on some of the equipment within the system. If this training is required, it should be conducted prior to but close to the date of installation. The staff then have a better understanding when assisting the installation.

8.7 Avoiding Problems

All automation projects generally have the following life cycle:

• Project initiation

• System design and manufacture

• Implementation

• Operation

It is possible for problems or failures to occur at any of these stages, and often, when a problem becomes apparent, the root cause occurred in an earlier stage of the project. In order to avoid problems, the teams must invest the appropriate time, resources and expertise into the project at an early stage. For example, detailed investigation in the concept stages provides a better understanding of the risks and potential problems, and therefore, it allows for actions to be taken to avoid these risks and minimise the problems. Notably, the cost required to rectify a problem or to resolve an issue normally increases as the project proceeds. An issue may cost a small amount to fix at the design stage, but the cost to rectify the same issue will be significantly increased if it does not come to light until the commissioning.

This section discusses a number of issues often found within automation projects, and it identifies how these issues might be avoided (Smith, 2001). The intent is to demonstrate how appropriate actions in the early stages of a project can avoid these problems and, therefore, why investment in the early stages of a project is worthwhile.

8.7.1 Project Conception

Project Based on an Unrealistic Business Case

The customer has built a justification for the project based on various assumptions. If these are found to be unrealistic, which may be due to the inexperience of the customer, the team should identify the problem and rebuild the business case based on more valid assumptions. Otherwise, the customer is disappointed at the end of the project, which is not beneficial for the vendor or the customer.

Project Based on State-of-Art or Immature Technology

This problem is relatively common with automation projects. The project initiator is over ambitious in terms of what the company can achieve and what current technology is available and affordable. The initiator should engage the appropriate expertise, even if this requires an external resource. If the only option is to apply unproven solutions, then the budget and timescales must include an allowance for the risk involved. In order to avoid later disputes, the company concerned, particularly the senior management, must be aware of the true risks prior to project commencement.

Lack of Senior Management Commitment

This issue can cause problems later in the project if the managers concerned have influence over one or more of the customer staff involved in the project. For example, if production management are less than supportive, the implementation and operation phases can be very difficult, even if the engineering management fully supports the system. Although difficult to address, vendors benefit from ensuring that the project has the full support of the customer’s staff. It is also beneficial for the project engineers, who are responsible for the project, to acquire support from all parties who may have some influence over the project during its complete life cycle.

Customer’s Funding and/or Timescale Expectations Are Unrealistic

When competing for a project, a vendor might find it difficult to disagree with a potential customer’s expectations for price and delivery. However, it is better to be honest up front and risk losing the business than to accept unrealistic challenges and then fail to deliver later. Provided the vendor’s position is justifiable, the straightforward and honest approach may also enhance the customer’s confidence in the vendor, resulting in the winning of the order and a better relationship with the customer.

8.7.2 Project Initiation

Vendor Setting Unrealistic Expectations on Cost, Timescale or Capability

The vendor might be very keen to win the business or might lack understanding about what may be involved in executing the project. These situations often result from a lack of experience in the vendor’s staff. It is not in the customer’s interest to place business with a vendor that has incurred unknown risks or maintains unrealistic expectations in order to win the business. The customer can assess this type of risk by obtaining and comparing multiple quotes, and by reviewing the expertise and resources of potential vendors, including assessing their previous experience via visits to reference sites.

Customer Failure to Define and Document Requirements

The lack of a specification (URS) is the most obvious example of this problem. In this case it is in the interest of the vendor to set out the assumptions behind its offer and to review these assumptions carefully and in detail with the customer. In effect, the vendor-generated assumptions then become the specification, providing the basis against which the project is judged.

Failure to Achieve an Equitable Relationship

The relationship between the customer and the vendor does not need to be friendly, but it does need to be open, equitable and based on mutual understanding. If the relationship is strained in the early stages, larger problems can develop as the project reaches a conclusion. If the personnel cannot be changed or no way can be found to improve the relationship, it may be better for the vendor to withdraw from the project.

Customer Staff’s Lack of Involvement

In these cases, the eventual end-users of the automation, such as the shop floor staff, have not been involved in project development and implementation. Although this lack of engagement is difficult address, it is in the vendor’s interest to encourage the customer to involve these end-users early on and to encourage their input and support for the project.

Poor Project Planning, Management, and Execution

This can occur on the customer or the vendor side, and it usually manifests as staff in a “fire fighting” mode. The normal cause is the definition and/or acceptance of unrealistic timing plans that do not correctly reflect the scale of the tasks involved or provide any contingency for risks. The problem may not be immediately solvable on a specific project, but lessons should be learnt and investments made, including training if appropriate, to improve for future projects. The costs of running late or over budget are often higher than the training cost incurred.

Failure to Clearly Define Roles and Responsibilities

This issue often arises between the customer and vendor when they share joint responsibilities for delivering the project. It is even more important when the project involves a number of vendors, all of whom are contracted directly by the customer to deliver elements of the project. The difficulties of dealing with multiple vendors leads many customers to insist on one lead vendor that has overall responsibility and project control, with all the other vendors contracted to them, a so-called turn-key project. This arrangement ensures one point of contact for the customer, but it also shifts the responsibility for ensuring appropriate demarcation to the main vendor.

The problems that emerge are gaps in the scope of supply or misunderstandings over interfaces. These often do not become apparent until later in the project, typically during installation and commissioning. Avoiding these issues requires a clear overall specification and very precise definitions of the roles and responsibilities of each vendor.

8.7.3 System Design and Manufacture

Failure to “Freeze” the Requirements and Apply Change Control

The customer may not have provided a specification or clearly defined the requirements, with various iterations also occurring during the quotation process. This dynamic may continue during the initial stages of the implementation. The vendor can easily continue to follow these changes until the cost implications are noticed at a late stage. The vendor then normally tries to recover these costs, which often causes problems between the customer and the vendor. It is much better to fix the specification and then document any changes as they are requested. At the same time, the vendor should notify the customer about the cost implications of these changes, providing the customer the option of reconsidering if the cost is higher than envisaged.

Vendor Starting a New Phase Prior to Completing the Previous One

The vendor can try to recover lost time or accelerate the project by running design and manufacture in parallel. This approach can be dangerous, and it should only be applied if the implications are known and the risks minimal. For example, some manufacture may commence before design is fully completed, if any changes in the design at that stage would have no implications on the manufacture already underway.

Failure to Undertake Effective Project Reviews

If the project proceeds without regular reviews and communication between the vendor and customer, problems are likely to emerge at a later stage. This may be a case when either party takes a “head in the sand” attitude regarding the avoidance of problem resolution. If problems are allowed to continue into later stages of the project, the ultimate resolution will only be more difficult than it would have been if the problem had been addressed earlier.

8.7.4 Implementation

Customer Failure to Manage the Changes Implicit in the Project

Particularly for a first project, the introduction of automation may require changes to the attitudes and possibly the working practises of some customer staff members. The system will only work successfully if those who operate and maintain the system wish it to work. Therefore, the customer must gain the support of all those who become involved. This should be done prior to implementation, and, if the vendor has concerns in this respect, it is worthwhile to raise these with the customer at an early stage in the project.

8.7.5 Operation

Inadequate User Training

This often becomes apparent when the vendor leaves the site, and the system does not then operate with the same performance or reliability as it did when the vendor was present. The vendor must ensure that the customer’s staff receives the appropriate training so it can operate and maintain the system as required.

Customer Fails to Maintain the System

Although difficult to influence, the vendor must ensure that the customer understands the need for appropriate maintenance if the system is to continue to operate as intended.

Customer Fails to Measure the Benefit of the Project

The project engineers who initially developed the business case for the project should ensure that the actual performance and output are measured to compare with the justification used to gain approval for the project. Any over performance should be highlighted, and any under performance investigated to provide guidance for future project justifications.

8.8 Summary

When undertaking automation projects, the most common mistakes made by customers include a lack of control of the input parts, failure to gain buy-in from the shop floor, failure to explain what is really required to the vendor and finally the selection of the vendor based purely on the lowest purchase cost. All of these mistakes are avoidable, however, given the appropriate approach to the project.

Automation highlights any input quality problems because it does not have the same flexibility as a manual operation. However, provided the parts input to the system can be controlled to achieve the parameters against which the system was designed, the overall quality of the output will improve.

The development of a detailed specification provides the basis for communicating the system requirements to the vendor. Without this specification, the vendor has no formal explanation of what is required, which can, and often does, lead to misunderstandings and disagreements later in the project. Therefore, this is an important document, and the customer should invest the time and resources required to provide a comprehensive specification (URS).

It is not surprising that the selection of the vendor is also critical. Yet, the customer often selects the lowest-cost vendor, with very little investigation of their capabilities. In such cases, a specification can provide some protection, but if the vendor fails to perform, the customer still incurs added cost. Again, the customer should invest the time required to fully investigate vendors and their expertise in order to ensure that the vendor selected is the most appropriate one for the project, even if that vendor did not offer the lowest quote.

A key part of any project is the two-way communication between the customer and vendor. The customer must explain the basic details of its requirements, the specification, and also cover the actual input tolerances, the details of the true operations, what is likely to go wrong and the flexibility needed. In turn, the vendor should explain the true production rate, including availability, the ramp-up time, the skills required to run the system, and the acceptable input tolerances. This needs to part of an open relationship that is not solely based on cost but also values expertise and experience. With a partnership between the vendor and customer, it is possible to overcome many problems, and the final results will be beneficial to both parties.

The customer must also encourage their staff to become involved, and it must provide training for the different people who will work with the system. This involvement generates familiarity with the equipment, removing the fear factor. It also gives the team the ability to quickly correct problems, and it creates ownership of the equipment, providing a desire to fix problems and ensure the system runs as planned. It also gives the customer the confidence to undertake improvements after the vendor has left, which may lead to greater output than planned. These benefits outweigh the cost of the training, which is therefore very worthwhile.

Finally, the actual performance and savings resulting from any automation projects should be compared to the original justification, and the final costs should be compared to the budget. This review indicates if the project met its objectives, and it also provides valuable lessons for future projects.