IR Management Handbook

Preparing for and responding to a computer security incident is challenging. With the ever-increasing pace of technology and change, it may seem like you can’t keep up. But we’ve learned some interesting things over our collective 30 years of responding to hundreds of incidents in organizations both large and small. With respect to this chapter, two specific points come to mind. First, most of the challenges to incident response are nontechnical. Second, the core principles of investigating a computer security incident do not differ from a nontechnical investigation. The real challenge is in looking past the buzzwords and marketing hype that attempts to convince you otherwise.

What we hope to provide in this chapter is information that will help you slice through the buzzwords, chop up the marketing hype, and focus on what is really important to build a solid incident response program. We will touch on a few basics, such as what a computer security incident is, what the goals of a response are, and who is involved in the process. Then we will cover the investigation lifecycle, critical information tracking, and reporting. We have found that organizations that spend time thinking about these areas perform incident response activities with much more success than those who did not.

WHAT IS A COMPUTER SECURITY INCIDENT?

Defining what a computer security incident is establishes the scope of what your team does and provides focus. It is important to establish that definition, so everyone understands the team’s responsibilities. If you don’t already have one, you should create a definition of what “computer security incident” means to your organization. There is no single accepted definition, but we consider a computer security incident to be any event that has the following characteristics:

• Intent to cause harm

• Was performed by a person

• Involves a computing resource

Let’s briefly discuss these characteristics. The first two are consistent with many types of common nontechnology incidents, such as arson, theft, and assault. If there is no intent to cause harm, it is hard to call an event an incident. Keep in mind that there may not be immediate harm. For example, performing vulnerability scans with the intent of using the results maliciously does not cause immediate detectable harm—but the intent to cause harm is certainly there. The third characteristic, requiring a person’s involvement, excludes events such as random system failures or factors beyond our control, such as weather. The fact that a firewall is down due to a power outage is not necessarily an incident, unless a person caused it, or takes advantage of it and does something they were not authorized to.

The final characteristic is what makes the incident a computer security incident: the event involves a computing resource. We use the term “computing resource” because there is a broad range of computer technology that fits in this category. Sometimes computing resources tend to go unnoticed—items such as backup media, phones, printers, building access cards, two-factor tokens, cameras, automation devices, GPS devices, tablets, TVs, and many others. Computing devices are everywhere, and sometimes we forget how much information is stored in them, what they control, and what they are connected to.

It may not be clear that an event is an incident until some initial response is performed. Suspicious events should be viewed as potential incidents until proven otherwise. Conversely, an incident investigation may uncover evidence that shows an incident was not truly a security incident at all.

Some examples of common computer security incidents are:

• Data theft, including sensitive personal information, e-mail, and documents

• Theft of funds, including bank access, credit card, and wire fraud

• Extortion

• Unauthorized access to computing resources

• Presence of malware, including remote access tools and spyware

• Possession of illegal or unauthorized materials

The impact of these incidents could range from having to rebuild a few computers, to having to spend a large amount of money on remediation, to the complete dissolution of the organization. The decisions you make, both before, during, and after an incident occurs will directly affect the impact.

WHAT ARE THE GOALS OF INCIDENT RESPONSE?

The primary goal of incident response is to effectively remove a threat from the organization’s computing environment, while minimizing damages and restoring normal operations as quickly as possible. This goal is accomplished through two main activities:

• Investigate

• Determine the initial attack vector

• Determine malware and tools used

• Determine what systems were affected, and how

• Determine what the attacker accomplished (damage assessment)

• Determine if the incident is ongoing

• Establish the time frame of the incident

• Remediate

• Using the information obtained from the investigation, develop and implement a remediation plan

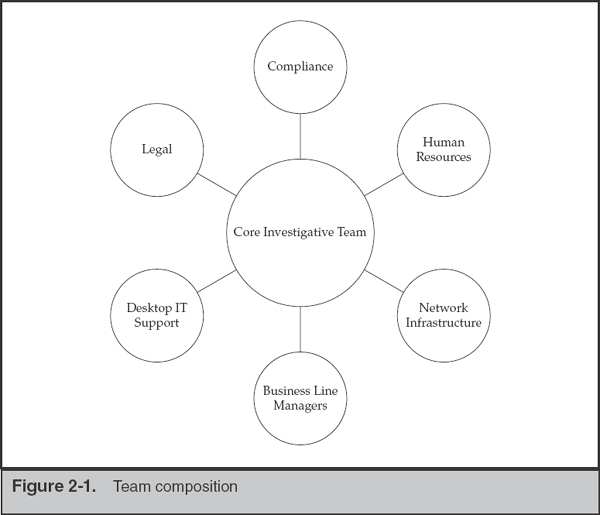

Incident response (IR) is a multifaceted discipline. It demands capabilities that require resources from several operational units in an organization. As Figure 2-1 shows, human resources personnel, legal counsel, IT staff, public relations, security professionals, corporate security officers, business managers, help desk workers, and other employees may find themselves involved in responding to a computer security incident.

During an IR event, most companies assemble teams of individuals that perform the investigation and remediation. An experienced incident manager, preferably someone who has the ability to direct other business units during the investigation, leads the investigation team. The importance of the last point cannot be overemphasized. The incident manager must be able to obtain information or request actions to be taken in a timely manner by any resource across the organization. This individual is often the CIO, CISO, or someone they directly appoint to work on their behalf. This person becomes the focal point for all investigative activities and manages the status of numerous tasks and requests that are generated. An experienced member of the IT staff leads the remediation team. This individual is the focal point for all remediation activities, including corrective actions derived from the investigation team’s findings, the evaluation of the sensitivity of stolen data, and the strategic changes that will improve the organization’s security posture.

Most organizations take a tiered and blended approach to staffing both investigative and remediation teams. Assembled and dedicated during the course of the investigation, the core teams often consist of senior IT staff, especially those with experience with log review, forensic analysis, and malware triage skills. The investigative team should have the ability to quickly access log repositories, system configurations, and, if an enterprise-wide IR platform is available, authority to conduct searches for relevant material. This core group of individuals may include consultants as well, to fill the operational gaps. Note that it may be acceptable for the consultants to lead the tactical investigation if their experience warrants it. The remediation team should have the authority to direct the organization to make the changes necessary to recover from the incident.

Authority to conduct searches at an enterprise scale can be a tricky thing. Regional and national law may limit the scope of searches, particularly in the European Union (EU). |

Ancillary teams that are assembled as required do not usually require staff dedicated to the investigation or remediation. Their contributions to the project are typically task oriented and performed as requested by the incident manager. Common members of ancillary teams include:

• Representatives from internal and external counsel

• Industry compliance officers (for example, PCI, HIPAA, FISMA, and NERC)

• Desktop and server IT support team members

• Network infrastructure team members

• Business line managers

• Human resource representatives

• Public relations staff

We’ll discuss the composition of the core investigative and remediation teams in Chapter 3; however, keep in mind that relationships and expectations must be set up in advance. The worst time to learn about requirements from counsel or your compliance people is in the middle of your investigation. You will be better off if you take the time to identify all reporting and process requirements applicable to your industry.

What should you be familiar with from a compliance perspective? If you have not already met with your internal compliance people, who very well may be your general counsel, take a day to chat about the lifecycle of an incident. Understand what information systems fall within scope and what reporting requirements are in place. In some situations, the question of scope has been addressed through other means (PCI DSS assessments, for example). Understand who should be informed of a potential intrusion or breach and what are the thresholds for notification defined by governance. Most importantly, identify the internal party responsible for all external communication and ensure that your teams are empowered to speak frankly to these decision-makers.

Your internal counsel should help determine the reporting thresholds they are comfortable with. The various parameters (time from event identification, likelihood of data exposure, scope of potential exposure) may not match those stated by external parties.

One industry that is notorious for imposing processes and standards on investigations is the Payment Card Industry. Once the card brands get involved in your investigation, your recovery is secondary to their goals of protecting their brands and motivating your organization to be PCI DSS compliant. |

Finding IR Talent

We work for a company that provides consulting services to organizations faced with tough information security problems. Given that point, you would expect that we would wholeheartedly support hiring consultants to help resolve an incident. It’s a bit like asking the Porsche representative if you really need their latest model. Our honest answer to the question of whether your company should use the services of or completely rely upon a consulting firm depends on many factors:

• Cost of maintaining an IR team Unless the operations tempo is high and demonstrable results are produced, many companies cannot afford or justify the overhead expense of maintaining experienced IR personnel.

• Culture of outsourcing Many organizations outsource business functions, including IT services. To our surprise, a number of top Fortune 50 companies outsource the vast majority of their IT services. We’ll discuss this trend and its implications to a successful IR in a later chapter.

• Mandated by regulatory or certification authorities An example of an external party that can dictate how you respond is the PCI Security Standards Council. If your company works with or is involved in the payment card industry, the Council may require that “approved” firms perform the investigation.

• Inexperience in investigations Hiring the services of an experienced consulting firm may be the best way to bootstrap your own IR team. Running investigations is a highly experiential skill that improves over time.

• Lack of or limited in-house specialization Investigations, particularly intrusion investigations, require a wide range of skills, from familiarity with the inner workings of operating systems, applications, and networking, to malware analysis and remediation processes.

With the exception of the situation where a company has virtually no internal IT capabilities, we have found that organizations that assemble an IR team on their own, however informally, stand a better chance of a successful investigation and timely resolution. This is true, even if the IR team is set up to handle only the initial phases of an investigation while external assistance is engaged.

When hiring external expertise to assist in your investigation, it is oftentimes advantageous to set up the contract through counsel, so that communications are reasonably protected from disclosure. |

How to Hire IR Talent

Hiring good people is a difficult task for most managers. If you have a team in place and are growing, identifying good talent can be easier: you have people who can assess the applicant’s skills and personality. Additionally, a precedent has been set, and you are already familiar with the roles you need filled and have in mind the ideal candidates for each. If you are in the all-too-common situation of an information security professional who has been tasked with creating a small IR team, where do you start? We suggest a two-step process: finding candidates, then evaluating them for qualifications and fit within your organization.

Finding Candidates Recruiting individuals from other IR teams is the obvious option. Posting open positions on sites such as LinkedIn is a good but passive way to reach potential candidates. Proactively targeting technical groups, related social networking sites, and message boards will yield quicker results, however. Many IR and forensic professionals of all skill levels lurk on message boards, such as Forensic Focus.

If you have the resources to contact the career offices of local universities, entry-level analysts and team members can be recruited from those with reputable computer science, engineering, or computer forensic programs. From our experience, the programs that begin with a four-year degree in computer science or engineering and have computer forensic minors or certificates produce the most well-rounded candidates, as opposed to those that attempt to offer everything in a single major. The fundamental skills that provide the greatest benefit to this field are the same as in most sciences: observation, communication, classification, measurement, inference, and prediction. The individuals possessing these skills typically make the best IR team members. If you can find a local university that focuses first on basic science or engineering skills and provides seminars or electives on forensic-related topics, you will be in good shape.

Assessing the Proper Fit: Capabilities and Qualities What capabilities do you require in your incident response team? Generally you want a team full of multitaskers—people with the knowledge and abilities to move between the different phases of an investigation. Looking across our own consulting group, we can come up with a number of relevant skill sets we would suggest. If you are hiring experienced candidates, you’ll want to consider people with the following qualifications:

• Experience in running investigations that involve technology This is a wide-spectrum ability that encompasses information and lead management, the ability to liaison with other business units, evidence and data management, and basic technical skills.

• Experience in performing computer forensic examinations This includes familiarity with operating system fundamentals, knowledge of OS and application artifacts, log file analysis, and the ability to write coherent documentation.

• Experience in network traffic analysis This includes experience with examination of network traffic and protocol analysis and the technology to put the information to use in a detection system.

• Knowledge of industry applications relevant to your organization Most companies have specialized information systems that process data on industry-specific platforms (for example, mainframe-hosted financial transactions).

• Knowledge of enterprise IT In the absence of an enterprise IR platform, nothing beats an administrator who can come up with a two-line script for searching every server under their control.

• Knowledge of malicious code analysis Malware analysis is an important skill to have on the team; however, most IR teams can get by performing basic automated analysis in a sandbox. If you have three positions available, hire multitaskers who have basic triage skills.

What qualities do we look for in an IR team member? During our interviews we attempt to discover whether the potential candidate has the following characteristics:

• Highly analytical

• Good communicator

• Attention to detail

• A structured and organized approach to problem solving

• Demonstrable success in problem solving

We are often asked about the applicability or relevance of the various industry certifications that dominate the IR and computer forensic fields. Generally, certifications that require periodic retesting and demonstration of continuing education serve as a nice indication that the person is actively interested in the field. When an applicant’s resume is low on experience, it can help us determine what areas in their background should be discussed in detail during interviews. In addition, if the papers written for the certification are available online, they give an indication to the application’s communication skills and writing style. It does not, however, appear to be a consistent indicator of the applicant’s true abilities. In fact, we have found there to be an inverse relationship between the depth of an applicant’s knowledge and the number of certifications they have pursued, when their employment history is sound. Vendor certifications are generally irrelevant to the hiring process because they demonstrate tool-specific skills as opposed to sound theory and procedural skills.

THE INCIDENT RESPONSE PROCESS

The incident response process consists of all the activities necessary to accomplish the goals of incident response. The overall process and the activities should be well documented and understood by your response team, as well as by stakeholders throughout your organization. The process consists of three main activities, and we have found that it is ideal to have dedicated staff for each:

• Initial response

• Investigation

• Remediation

Initial response is an activity that typically begins the entire IR process. Once the team confirms that an incident is under way and performs the initial collection and response steps, the investigation and remediation efforts are usually executed concurrently. The investigative team’s purpose is solely to perform investigatory tasks. During the investigation, this team continually generates lists of what we call “leads.” Leads are actionable items about stolen data, network indicators, identities of potential subjects, or issues that led to the compromise or security incident. These items are immediately useful to the remediation team, whose own processes take a significant amount of time to coordinate and plan. In many cases, the activity that your team witnesses may compel you to take immediate action to halt further progress of an intrusion.

Initial Response

The main objectives in this step include assembling the response team, reviewing network-based and other readily available data, determining the type of incident, and assessing the potential impact. The goal is to gather enough initial information to allow the team to determine the appropriate response.

Typically, this step will not involve collecting data directly from the affected system. The data examined during this phase usually involves network, log, and other historical and contextual evidence. This information will provide you the context necessary to help decide the appropriate response. For example, if a banking trojan is found on the CFO’s laptop, your response will probably be quite different than if it is found on a receptionist’s system. Also, if a full investigation is required, this information will be part of the initial leads. Some common tasks you may perform during this step are:

• Interview the person(s) who reported the incident. Gather all the relevant details they can provide.

• Interview IT staff who might have insight into the technical details of an incident.

• Interview business unit personnel who might have insight into business events that may provide a context for the incident.

• Review network and security logs to identify data that would support that an incident has occurred.

• Document all information collected from your sources.

Investigation

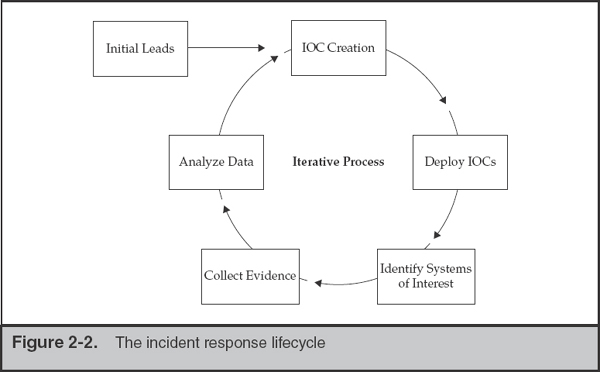

The goal of an investigation is to determine facts that describe what happened, how it happened, and in some cases, who was responsible. As a commercial IR team, the “who” element may not be attainable, but knowing when to engage external help or law enforcement is important. Without knowing facts such as how the attacker gained access to your network in the first place, or what the attacker did, you are not in a good position to remediate. It may feel comforting to simply pull the plug and rebuild a system that contains malware, but can you sleep at night without knowing how the attacker gained access and what they did? Because we value our sleep, we’ve developed and refined a five-step process, shown in Figure 2-2, that promotes an effective investigation. In the following sections, we cover each of the five steps in detail.

Maybe It’s Best Not to Act Quickly

During an investigation, you will likely come across discoveries that you feel warrant immediate action. Normally, the investigation team immediately reports any such critical findings to the appropriate individual within the affected organization. The individual must weigh the risk of acting without a sufficient understanding of the situation versus the risk of additional fact-finding activities. Our experience is that, in more cases than not, it is important to perform additional fact-finding so you can learn more about the situation and make an appropriate decision. This approach certainly has risk because it may provide the attacker with further opportunity to cause harm. However, we have found that taking action on incomplete or inaccurate information is far more risky. There is no final answer, and in each incident, your organization must decide for itself what is acceptable.

An investigation without leads is a fishing expedition. So, the collection of initial leads is a critical step in any investigation. We’ve noticed a common investigative misstep in many organizations: focus only on finding malware. It is unlikely that an attacker’s only goal is to install malware. The attacker probably has another objective in mind, perhaps to steal e-mail or documents, capture passwords, disrupt the network, or alter data. Once the attacker is on your network and has valid credentials, they do not need to use malware to access additional systems. Focusing only on malware will likely cause you to miss critical findings.

Remember, the focus of any investigation should be on leads. We have responded to many incidents where other teams completed investigations that uncovered few findings. In many cases, the failure of prior investigations was due to the fact that the teams did not focus on developing valid leads. Instead, they focused on irrelevant “shiny objects” that did not contribute to solving the case. There are numerous incidents where we found significant additional findings, such as substantial data loss, or access to sensitive computer systems, simply by following good leads.

Often overlooked is the process of evaluating new leads to ensure they are sensible. The extra time you spend evaluating leads will help the investigation stay focused. In our experience, there are three common characteristics of good leads:

• Relevant The lead pertains to the current incident. This may seem obvious, but is often overlooked. A common trap organizations fall into is categorizing anything that seems suspicious as part of the current incident. Also, an incident prompts many organizations to look at their environment in ways they never have before, uncovering many “suspicious activities” that are actually normal. This quickly overwhelms the team with work and derails the investigation.

• Detailed The lead has specifics regarding a potential course of investigation. For example, an external party may provide you with a lead that indicates a computer in your environment communicated with an external website that was hosting malware. Although it was nice of them to inform you, this lead is not very specific. In this case, you need to pry for more details. Ask about the date and time of the event and IP addresses—think who, what, when, where, why, and how. Without these details, you may waste time.

• Actionable The lead contains information that you can use, and your organization possesses the means necessary to follow the lead. Consider a lead that indicates a large amount of data was transferred to an external website associated with a botnet. You have the exact date, time, and destination IP address. However, your organization does not have network flow or firewall log data available to identify the internal resource that was the source of the data. In this case, the lead is not very actionable because there is no way to trace the activity to a specific computer on your network.

Indicators of Compromise (IOC) Creation

IOC (pronounced eye-oh-cee) creation is the process of documenting characteristics and artifacts of an incident in a structured manner. This includes everything from both a host and network perspective—things beyond just malware. Think about items such as working directory names, output file names, login events, persistence mechanisms, IP addresses, domain names, and even malware network protocol signatures. The goal of IOCs is to help you effectively describe, communicate, and find artifacts related to an incident. Because an IOC is only a definition, it does not provide the actual mechanism to find matches. You must create or purchase technology that can leverage the IOC language.

An important consideration in choosing how to represent IOCs is your ability to use the format within your organization. Network indicators of compromise are most commonly represented as Snort rules, and there are both free and commercial enterprise-grade products that can use them. From a host perspective, some of the IOC formats available are:

• Mandiant’s OpenIOC (www.openioc.org)

• Mitre’s CybOX (cybox.mitre.org)

• YARA (code.google.com/p/yara-project)

For two of these formats, OpenIOC and YARA, there are free tools available to create IOCs. Mandiant created a Windows-based tool named IOC Editor that will create and edit IOCs based on the OpenIOC standard. For YARA, there are a number of tools to create and edit rules, or even automatically create rules based on a piece of malware. We talk more about what makes up a good IOC and how to create one in Chapter 5.

GO GET IT ON THE WEB

IOC Deployment

Using IOCs to document indicators is great, but their real power is in enabling IR teams to find evil in an automated fashion, either through an enterprise IR platform or through visual basic (VB) and Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) scripting. The success of an investigation depends on your ability to search for IOCs across the enterprise and report on them in an automated way—this is what we mean by “IOC deployment.” Therefore, your organization must possess some capability to implement IOCs, or they are not much use. For network-based IOCs, the approach is straightforward—most solutions support Snort rules. However, as discussed earlier, there is not yet an accepted standard for host-based IOCs. Because of this, effectively using host-based IOCs in your investigative process may be challenging. Let’s take a look at some current options.

Industry and IOC Formats

There is a major deficiency in the computer security industry when it comes to host-based indicators of compromise: there is no accepted standard. Although Snort was created and accepted as the de-facto standard for network-based IOCs, there is no free host-based solution that includes an indicator language and the tools to effectively use it in an enterprise. Without a solution, incident responders will continue to face significant challenges looking for host-based IOCs on investigations.

At the time we wrote this book, the three dominant host-based IOC definitions were Mandiant’s OpenIOC, Mitre’s CybOX, and YARA. Let’s take a quick look at each one. YARA provides a language and a tool that is fairly mature; however, the scope of artifacts covered by YARA is primarily focused only on malware. Mandiant’s OpenIOC standard is much more comprehensive and has a publicly available IR collection tool called Redline to use with the OpenIOCs. However, OpenIOC is not yet mature or widely accepted. Mitre’s CybOX standard is also comprehensive, but no tools are available other than IOC format conversion scripts. And for all three of these options, no enterprise-grade or mature solution is freely available, as there is with Snort.

You don’t need a large budget to use IOCs, although your ability to effectively use them across an enterprise will likely require significant funding. There are both free and commercial tools that can use the YARA and OpenIOC standards to search for IOCs. On the free side, the YARA project provides tools to search for YARA rules. Also, a number of open source projects can use YARA rules, some of which are listed in the YARA tools link we provided earlier. Mandiant provides a free tool, Redline, that you can use to search for OpenIOCs on systems. These free tools are quite effective on a small number of systems, but do not scale up very well. To effectively search for an IOC in an enterprise, you will need to invest in a large-scale solution. For example, FireEye can use YARA rules, and Mandiant’s commercial software offerings can use OpenIOCs. Keep in mind, though, that the software and processes that support using IOCs are still not very mature. This aspect of the security industry is likely to change in the coming years, so stay tuned for developments.

Identify Systems of Interest

After deploying IOCs, you will begin to get what we call “hits.” Hits are when an IOC tool finds a match for a given rule or IOC. Prior to taking action on a hit, you should review the matching information to determine if the hit is valid. This is normally required because some hits have a low confidence because they are very generic, or because of unexpected false positives. Sometimes we retrieve a small amount of additional data to help put the hit in context. Unless the hit is high confidence, at this point it’s still unknown whether or not the system is really part of the incident. We take a number of steps to determine if the system is really of interest.

As systems are identified, you should perform an initial triage on the new information. These steps will help to ensure you spend time on relevant tasks, and keep the investigation focused:

• Validate Examine the initial details of the items that matched and determine if they are reliable. For example, if an IOC matches only on a file’s name, could it be a false positive? Are the new details consistent with the known time frame of the current investigation?

• Categorize Assign the identified system to one or more categories that keep the investigation organized. Over the years, we’ve learned that labeling a system as “Compromised” is too vague, and investigators should avoid using that term as much as possible. We have found it more helpful to use categories that more clearly indicate the type of finding and the attacker’s activities, such as “Backdoor Installed,” “Access With Valid Credentials,” “SQL Injection,” “Credential Harvesting,” or “Data Theft.”

• Prioritize Assign a relative priority for further action on the identified system. A common practice within many organizations is to prioritize based on business-related factors such as the primary user or the type of information processed. However, this approach is missing a critical point in that it does not consider other investigative factors. For example, if the initial details of the identified system’s compromise are consistent with findings from other systems, further examination of this system may not provide any new investigative leads and could be given a lower priority. On the other hand, if the details suggest something new, such as different backdoor malware, it may be beneficial to assign a higher priority for analysis, regardless of other factors.

Preserve Evidence

Once systems are identified and have active indicators of compromise, the next step is to collect additional data for analysis. Your team must create a plan for collecting and preserving evidence, whether the capability is in house or outsourced. The primary goals when preserving evidence are to use a process that minimizes changes to a system, minimizes interaction time with a system, and creates the appropriate documentation. You may collect evidence from the running system or decide to take the system down for imaging.

Because any team has limited resources, it does not make sense to collect large volumes of data that may never be examined (unless there is good reason). So, for each new system identified, you must make a decision about what type of evidence to collect. Always consider the circumstances for each system, including if there is anything different about the system or if a review of live response data results in new findings. If you believe there is some unique aspect, or there is another compelling reason, preserve the evidence you feel is necessary to advance the investigation. The typical evidence preservation categories are live response, memory collection, and forensic disk image, as detailed next:

• Live response Live response is the most common evidence collection process we perform on an incident response. A live response is the process of using an automated tool to collect a standard set of data about a running system. The data includes both volatile and nonvolatile information that will rapidly provide answers to investigative questions. The typical information collected includes items such as a process listing, active network connections, event logs, a list of objects in a file system, and the contents of the registry. We may also collect the content of specific files, such as log files or suspected malware. Because the process is automated and the size of the data is not too large, we perform a live response on most systems of interest. A live response analysis will usually be able to further confirm a compromise, provide additional detail about what the attacker did on the system, and reveal additional leads to investigate.

• Memory collection Memory collection is most useful in cases where you suspect the attacker is using a mechanism to hide their activities, such as a rootkit, and you cannot obtain a disk image. Memory is also useful for cases where the malicious activity is only memory-resident, or leaves very few artifacts on disk. In the majority of systems we respond to, memory is not collected, however. Although some may find this surprising, we have found that analyzing memory has limited benefits to an investigation because it does not provide enough data to answer high-level questions. Although you may be able to identify that malware is running on a system, you will likely not be able to explain how it got there, or what the attacker has been doing on that system.

• Forensic disk image Forensic disk images are complete duplications of the hard drives in a system. During an incident response, it is common for us to collect images in a “live” mode, where the system is not taken offline and we create an image on external media. Because disk images are large and can take a long time to analyze, we normally collect them only for situations where we believe a disk image is necessary to provide benefit to the investigation. Forensic disk images are useful in cases where an attacker performed many actions over a long time, when there are unanswered questions that other evidence is not helping with, or where we hope to recover additional information that we believe will only be available from a disk image. In incidents that do not involve a suspected intrusion, full disk image collection is the norm.

Analyze Data

Analyzing data is the process of taking the evidence preserved in the previous step and performing an examination that is focused on answering the investigative questions. The results of the analysis are normally documented in a formal report. This step in the incident response lifecycle is where we usually spend most of our time. Your organization must decide what analysis you will perform on your own, and what portions, if any, you will outsource. There are three major data analysis areas:

• Malware analysis During most investigations, we come across files that are suspected malware. We have a dedicated team of malware analysts that examines these files. They produce reports that include indicators of compromise and a detailed description of the functionality. Although having a dedicated malware team doesn’t fit into most budgets, organizations should consider investing in a basic capability to triage suspected malware.

• Live response analysis Examining the collected live response data is one of the more critical analysis steps during an investigation. If you are looking at live response data, it’s normally because there is some indication of suspicious activity on a system, but there are limited details. During the analysis, you will try to find more leads and explain what happened. If details are missed at this stage, the result could be that you overlook a portion of the attacker’s activity or you dismiss a system entirely. The results of live response analysis should help you understand the impact of the unauthorized access to the system and will directly impact your next steps. Every organization performing IT security functions should have a basic live response analysis capability.

• Forensic examination A forensic examination performed on disk images during an incident response is a very focused and time-sensitive task. When bullets are flying, you do not have time to methodically perform a comprehensive examination. We normally write down a handful of realistic questions we want answered, decide on an approach that is likely to uncover information to answer them, and then execute. If we don’t get answers, we may use a different approach, but that depends on how much time there is and what we expect to gain from it. This is not to say we don’t spend a lot of time performing examinations—we are just very conscious of how we spend our time. If the incident you are responding to is more traditional, such as an internal investigation that does not involve an intrusion, this is the analysis on which you will spend most of your time. There is a degree of thoroughness applied to traditional media forensic examinations that most IR personnel and firms have no experience in.

When performing intrusion analysis, remember that you may not “find all the evidence.” We’ve worked with organizations that suffer from what we sometimes call the “CSI effect,” where the staff believes they can find and explain everything using “cool and expensive tools.” We collectively have decades of experience performing hundreds of incident response investigations, and during all of these investigations, we have yet to come across such a magic tool. Granted, there are tools that can greatly benefit your team. However, some of the best tools to use are ones you already have—you are using them now, to read and understand this sentence.

Other types of investigations rely on a very methodical process during forensic examinations. The goal is to discover all information that either supports or refutes the allegation. If your team’s charter includes other types of investigations, be aware of how to scale your effort appropriately and maintain the skills necessary to answer other types of inquiries. In this edition we are focusing on taking an intrusion investigation from detection to remediation in a rapid but thorough manner on an enterprise scale. |

Remediation

Remediation plans will vary greatly, depending on the circumstances of the incident and the potential impact. The plan should take into account factors from all aspects of the situation, including legal, business, political, and technical. The plan should also include a communication protocol that defines who in the organization will say what, and when. Finally, the timing of remediation is critical. Remediate too soon, and you may fail to account for new or yet-to-be-discovered information. Remediate too late, and considerable damage could occur, or the attacker could change tactics. We have found that the best time to begin remediation is when the detection methods that are in place enter a steady state. That is, the instrumentation you have configured with the IOCs stop alerting you to new unique events.

We recommend starting remediation planning as early in the incident response process as possible so that you can avoid overtasking your team and making mistakes. Some incidents require significantly more effort on remediation activities than the actual investigation. There are many moving parts to any organization, and undertaking the coordination of removing a threat is no easy task. The approach we take is to define the appropriate activities to perform for each of the following three areas:

• Posturing

• Tactical (short term)

• Strategic (long term)

Posturing is the process of taking steps that will help ensure the success of remediation. Activities such as establishing protocol, exchanging contact information, designating responsibilities, increasing visibility, scheduling resources, and coordinating timelines are all a part of the posturing step. Tactical consists of taking the actions deemed appropriate to address the current incident. Activities may include rebuilding compromised systems, changing passwords, blocking IP addresses, informing customers of a breach, making an internal or public announcement, and changing a business process. Finally, throughout an investigation, organizations will typically notice areas they can improve upon. However, you should not attempt to fix every security problem that you uncover during an incident; make a to-do list and address them after the incident is over. The Strategic portion of remediation addresses these areas, which are commonly long-term improvements that may require significant changes within an organization. Although strategic remediation is not part of a standard IR lifecycle, we mention it here so that you are aware of this category and use it to help stay focused on what is important.

Tracking of Significant Investigative Information

We mentioned earlier in this chapter that many of the challenges to effective incident response are nontechnical. Staying organized is one of those challenges, and is an especially big one. We hate to use the term “situational awareness,” but that’s what we are talking about here. Your investigations must have a mechanism to easily track critical information and share it with the ancillary teams and the organization’s leadership. You should also have a way to refer to specific incidents, other than “the thing that started last Tuesday.” Establish an incident numbering or naming system, and use that to refer to and document any information and evidence related to a specific incident.

What is “significant investigative information”? We have found a handful of data points that are critical to any investigation. These items must be tracked as close to real time as possible, because team members will use them as the “ground truth” when it comes to the current status of the investigation. This data will also be the first thing that team members will reference when queries come in from management.

• List of evidence collected This should include the date and time of the collection and the source of the data, whether it be an actual person or a server. Ensure that a chain of custody is maintained for each item. Keep the chain of custody with the item, and its presence in this list is an indicator to you that an item has been handled properly.

• List of affected systems Track how and when the system was identified. Note that “affected” includes systems that are suspected of a security compromise as well as those simply accessed by a suspicious account.

• List of any files of interest This list usually contains only malicious software, but may also contain data files or captured command output. Track the system the file was found on as well as the file system metadata.

• List of accessed and stolen data Include file names, content, and the date of suspected exposure.

• List of significant attacker activity During examinations of live response or forensic data, you may discover significant activities, such as logins and malware execution. Include the system affected and the date and time of the event.

• List of network-based IOCs Track relevant IP addresses and domain names.

• List of host-based IOCs Track any characteristic necessary to form a well-defined indicator.

• List of compromised accounts Ensure you track the scope of the account’s access, local or domain-wide.

• List of ongoing and requested tasks for your teams During our investigations, we usually have scores of tasks pending at any point. From requests for additional information from the ancillary teams, to forensic examinations, it can be easy to let something fall through the cracks if you are not organized.

At the time we wrote this book, we were in a transition phase from our tried-and-true Microsoft Excel spreadsheet with 15 tabs to a streamlined multiuser web interface. We decided to build our own system, because we could not find an existing case and incident management solution that met our needs. It was a long time coming, and was extremely challenging because Excel provides flexibility and ease of use that is hard to replicate in a web interface. Whatever you decide to use at your organization, it needs to be as streamlined as possible into your processes.

GO GET IT ON THE WEB

Incident management systems

A few years back, we performed an investigation at a small defense contractor that had a network consisting of about 2,000 hosts. Compared to some of our larger investigations, tipping the scales at environments with 100,000+ hosts, this investigation seemed like it would be easy. We started to ask ourselves if completing all of our normal documentation was necessary, especially because the organization was very cost sensitive. However, one thing led to another, and the next thing we knew, we uncovered almost 200 systems with confirmed malware, and even more that were accessed with valid credentials! Some were related to the incident we were hired to investigate, and some were not. Without our usual documentation, the investigation would have lost focus and wasted much more time than it took to create the documentation. The lesson that was reinforced on that incident was to always document significant information during an incident, no matter how large or small.

Reporting

As consultants, our reports are fundamental deliverables for our customers. Creating good reports takes time—time you may think is best spent on other tasks. However, without reports, it is easy to lose track of what you’ve done. We’ve learned that even within a single investigation, there can be so many findings that communicating the totality of the investigation would have been difficult without formal, periodic reports. In many investigations, the high-level findings are based on numerous technical facts that, without proper documentation, may be difficult to communicate.

We believe reports are also a primary deliverable for incident response teams, for a few reasons. Reports not only provide documented results of your efforts, but they also help you to stay focused and perform quality investigations. We use a standard template and follow reporting and language guidelines, which tends to make the reporting process consistent. Reporting forces you to slow down, document findings in a structured format, verify evidence, and think about what happened.

Nearly everyone has experienced an interesting consequence of documentation. It’s similar to what happens when you debate writing a task on a to-do list. If you don’t write the task down, there’s a higher chance you will forget to do it. Once you perform the physical process of writing, you likely don’t even have to go back and look at the list—you just remember. We’ve found that writing, whether it consists of informal notes or formal reports, helps us remember more, which in turn makes us better investigators.

We cover report writing in detail in Chapter 17.

In this chapter we’ve presented information that we hope managers will find useful in establishing or updating their incident response capabilities. The following checklist contains the tasks we believe you should consider first as you go through the process:

• Define what a “computer security incident” means in your organization.

• Identify critical data, including where it is stored and who is responsible for it.

• Create an incident tracking process and system for identifying distinct incidents.

• Understand the legal and compliance requirements for your organization and the data you handle.

• Define the capabilities you will perform in house, and what will be outsourced.

• Find and train IR talent.

• Create formal documentation templates for the incident response process.

• Create procedures for evidence preservation on the common operating systems in your environment.

• Implement network-based and host-based solutions for IOC creation and searching.

• Establish reporting templates and guidelines.

• Create a mechanism or process to track significant investigative information.

QUESTIONS

1. List the groups within an organization that may be involved in an incident response. Explain why it is important to communicate with those groups before an incident occurs.

2. Your organization receives a call from a federal law enforcement agency, informing you that they have information indicating a data breach occurred involving your environment. The agency provides a number of specific details, including the date and time when sensitive data was transferred out of your network, the IP address of the destination, and the nature of the content. Does this information match the characteristics of a good lead? Explain why or why not. What else might you ask for? How can you turn this information into an actionable lead?

3. Explain the pros and cons of performing a live response evidence collection versus a forensic disk image. Why is a live response the most common method of evidence preservation during an IR?

4. During an investigation, you discover evidence of malware that is running on a system. Explain how you would respond, and why.

5. Explain why creating and searching for IOCs is a critical part of an investigation.

6. When does the remediation process start, and why?

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.