chapter three

The tools of internal

marketing

As we have seen, a central plank of internal marketing is the use of marketing-like techniques to motivate employees. The question inevitably arises as to how useful are concepts techniques such as customers, segmentation, market research, and the marketing mix for developing customer-oriented behaviour and generally motivating employees? This is a pertinent question, as motivation of employees has traditionally been the realm of human resource management (HRM). In the following discussion, we examine how and the extent to which it is possible to use marketing techniques to motivate employees. This section takes up these questions, dealing firstly with application of the customer concept internally and then moving on to the various elements of the marketing mix, segmentation and market research techniques. The final section shows how IM was used to facilitate the implementation of a marketing strategy in the financial services sector.

Internal customers

Central to the marketing philosophy are the concepts of customer and exchange, namely that customers receive products they desire in exchange for payment of some kind (that is, a price). In the external marketing exchange situation, products are bought in order to derive some form of utility or satisfaction. Applying these concepts internally, as is implied by treating ‘employees as customers’, the concepts require some care.

Firstly, one of the main problems with this approach is that the ‘products’ that employees are being sold may be unwanted or may in fact have negative utility for them; that is, they may not want them (e.g. new methods of working). In normal marketing situations, customers do not have to buy products that they do not wish to buy. This is not true for employees, as they must either accept the ‘product’ or (in the final analysis) they can be ‘forced’ into acceptance under the threat of disciplinary action or dismissal. In normal marketing situations, the consequences of non-purchase are not so severe. Additionally, in normal marketing situations customers have a range of (competing) products to choose from; this is unlikely to be the case in an internal marketing situation, where one particular policy will be on offer. That is, the marketing approach consists of non-coercive actions to induce a response in another social unit1. Therefore, the use of force or formal authority is not considered to be a marketing solution to a problem.

Another problem with the notion of the employee as customer is the idea of customer sovereignty (that is the idea of customer is king, customer is always right and so forth). For, if employees were to behave like external customers, they would make impossible demands upon the organization and its resources. It is for this reason that in this approach employees do not know they are customers even though they are treated as such!

Moreover, the idea put forward by some that ‘personnel is the first market of a service company’ appears to suggest that the employee market has primacy2. This stands on its head the most fundamental axiom of marketing that the external customer has primacy. For it is the external customer that is the raison d’être of any company. For instance, many restaurant workers would prefer not to work late hours, but nevertheless have to because that is when the customers prefer to dine out. Accommodating employee preferences in this case would lead to commercial suicide.

Given the above caveats, the marketing principle of creating products that their internal customers want is rapidly gaining ground in all types of organizations. For instance, in the British National Health Service, human resource development trainers are increasingly shifting their practices away from product orientation to a market orientation. That is, instead of putting on courses that the trainers wanted to do or enrolling candidates on courses simply to achieve targets, they are now shifting toward providing training and courses that internal customers demand, whether they are senior management, line managers or other employees3.

The problems associated with ‘employees as customers’ are largely avoided in the total quality management (TQM) concept of internal customers, as the emphasis is on relationships between employees themselves rather than between the organization and the employees. In the TQM approach, employees make demands upon each other rather than their organization. Furthermore, the types of demands that they can make upon each other are limited to ensuring that they, as suppliers, deliver ‘products’ that meet their ‘customers’ requirements and vice versa. If these requirements are met along the entire length of the production chain, then the quality of the final product will be assured.

The degree of customer orientation and co-ordination between different organizations depends on the degree and type of interdependence that exists between groups in organizations. Three types of interdependence can be distinguished, namely sequential interdependence, pooled interdependence and reciprocal interdependence4. For instance, in a manufacturing setting, where production largely progresses linearly, that is, where the output of one group is the input of another, and so on down the line, there is sequential interdependence between different groups or departments, similar to the TQM approach mentioned above. This situation is likely to be characterized by moderate levels of customer orientation and co-ordination between groups.

In situations of pooled interdependency, that is, cases where work does not flow between groups or departments, and they make separate and independent contributions to overall organizational or departmental goals (for instance, sales teams assigned to separate geographic areas of the target market), there is likely to be little concern for customer orientation or collaboration.

Reciprocal interdependence occurs where there is back and forth flow of work between groups. Such a situation requires a high level of collaboration between all the groups involved. Such a situation is typical in health care settings, where highly interdependent teamwork is required for complex patient treatment, frequently requiring multiple inputs from specialist teams and support services. In such a situation, the need for internal customer orientation is high and dominant, because the output of one group typically serves as the input for a second area, and the output of the second area might flow back as input for the first group again. In areas of high reciprocal interdependence, therefore, one would expect greater effort devoted by managers towards internal customer orientation. This is necessary in order to increase the sharing of expertise, the resolution of conflicts and priorities, and the sharing of the common goal of serving patient needs. Research evidence suggests that high level co-ordination of objectives increases both employee and patient satisfaction5.

Developing an internal marketing mix

The idea behind the internal marketing mix concept is that a number of elements under the control of management are combined and integrated in order to produce the required response from the target market. Attempts at applying the marketing mix concept to internal marketing have been structured generally around the 4Ps marketing mix (Product, Promotion, Price and Place) framework6. However, because of the intangible nature of the product being ‘marketed’ in the internal marketing context (for instance, the idea of a customer-conscious employee), we propose that the extended marketing mix for services is used7. That is, it is proposed that in addition to the traditional 4Ps of product marketing (namely Product, Price, Promotion and Place), Physical Evidence, Process and Participants need to be added. This is because the extended 7Ps marketing mix (in particular the Process and Participants concepts) explicitly recognizes inter-functional interdependence and the need for an integrated effort for effective service (or product) delivery. An integrated effort is, after all, one of the major aims of an internal marketing programme. We begin the discussion of the application of the marketing mix to internal marketing with the product concept.

Product

At the strategic level, the product can refer to marketing strategies; what is sold is those values and attitudes needed to make a plan work. At the tactical level, the product could include new performance measures and new ways of handling customers. Product can also be used to refer to services and training courses provided by HRM. At a more fundamental level the product is the job8. In order to achieve acceptance of new initiatives, managers need to concentrate on the benefits of the product rather than its features. That is, managers should concentrate on explaining the benefits of new initiatives to the customers, to the organization, and consequently the employees themselves. Treating jobs as products means looking at jobs not only from the point of view of the tasks that need to be performed, but also from the perspective of the employees and the benefits they seek from the job. This means giving consideration not only to financial remuneration, but also to training needs, level of responsibility and involvement in decision making, career development opportunities, and the working environment, amongst other factors that employees value. Treating jobs in this way will facilitate the hiring retention and the motivation of employees. Also, treating jobs as products is a reminder that jobs need to be marketed well in order to recruit the best possible employees.

Price

Price can refer to the psychological cost of adopting to new methods of working, projects that have to be foregone in order to carry out new policies (i.e. the opportunity cost), or to transfer pricing and expense allocation between departments. As opportunity costs are difficult to measure precisely (unlike the monetary price of goods and services), employees may tend to overestimate the costs of undertaking new practices and hence be inclined to resist changes. In order to avoid this, the benefits of adopting the new policies need to be clearly explained and any fears allayed by providing employees with appropriate information.

Exhibit 3.1. Internal communications at Lloyds TSB

Large corporations are increasingly realizing the importance of using internal marketing for inculcating their corporate culture brand values. This is partly due to the increasing number of mergers, which create problems of integrating different corporate and brand cultures. Such situations require a planned programme of internal communications and just a speech or two from the new CEO. This is well illustrated by the Lloyds TSB merger in 1995 and its launch as a brand in its own right in 1999.

On 1 August 1995, Cheltenham & Gloucester (C&G) became part of the Lloyds Bank Group. In December of the same year, Lloyds Bank Group merged with TSB Group to form Lloyds TSB Group plc. In September 1996, Lloyds Abbey Life became a wholly owned subsidiary of Lloyds TSB Group. The merger created a single bank with around 77 000 employees and 15 million customers. However, Lloyds TSB needed to integrate its employees and offer its customers an integrated range of products and brand propositions that the customers understood. It was not until November 1998 that a full-scale pilot was launched in Norwich, with 13 branches offering a single branded service and product range to customers of both banks under the Lloyds TSB name. On 28 June 1999, Lloyds TSB was launched on the high street. The launch was accompanied by a new advertising campaign.

The bank realized that if it were to communicate its new brand values effectively to its customers it needed to communicate these values first to its employees and to motivate them to deliver the brand. Hence, prior to the full launch the bank instigated a comprehensive and sustained internal marketing programme. A key component of the programme was a live event at the NEC in Birmingham called ‘Your Life. Your Bank’, a month before the full launch. The objectives of the event were to reveal the new blue and green corporate identity, explain the values behind the brand, and gain commitment from the employees to new culture and the new methods of working required to deliver the brand.

The problem that Lloyds TSB faced was how to get its entire workforce of 77 000 on message. The method that it hit on, with the help of the events organizer Caribiner, was to ask all its staff to nominate a ‘pathfinder’, or a brand ambassador, who would attend the event and then take the messages back to 15 of their colleagues.

A total of 5000 staff acted as pathfinders, about 2000 of whom were the senior people, with the remainder coming from all ranks.

The event comprised a 28-stand exhibition, representing all of the bank's departments. A number of presentations explored how Lloyds and TSB were coming together, whilst others focused on understanding the brand. There were contributions from all levels, from top management to the people who had put up the new signage. The event was compered by Carol Vorderman and climaxed with the arrival on stage of Irish pop band The Corrs, whose music featured in the new advertising campaign.

After the event, pathfinders passed on the knowledge that they had acquired about the new brand to their colleagues in prearranged meetings. They were equipped with packs containing summaries of key points, overhead transparencies and a video summary for this task. Research conducted among pathfinders before and after the live event showed that the pathfinders found that there was strong and positive change in their attitudes towards the impact of the changes on customers, employees and the excitement about the new company. The research also showed that the pathfinder approach had been successful in conveying the messages to staff who had not attended the event.

On the day of the full launch of the new brand, the bank's chief executive addressed the staff live on business TV and all staff received a letter welcoming them to their new bank.

Sources: Anonymous (2000). Internal communications. Marketing, 6 June, p. 19. Murphy, C. (2000). Instilling workers with brand values. Marketing, 27 January, pp. 31–2. Miller, R. (1999). Going live can put staff fears to rest. Marketing, 4 November, pp. 35–6. Anonymous (1999). Case study: Lloyds/TSB merger. Marketing, 4 November, p. 36. Lloyds TSB plc website (www.lloydstsb.com).

Internal communications/Promotion

Promotion in the context of the marketing mix refers to the use of advertising, publicity, personal selling (face-to-face presentations/communications) and sales promotions (incentives to purchase) in order to inform and to influence potential customers’ attitudes towards a firm's products.

Motivating employees and influencing their attitudes is obviously an important aspect of internal marketing and hence the importance of getting the internal communications strategies right.

Human resource managers already use a wide variety of techniques and media to communicate with employees, ranging from oral briefings and company newspapers to corporate videos. However, for effective communication what is necessary is a co-ordinated use of these various media. Interest in new policies and training courses, for instance, can be generated by publicizing them in company newspapers and on company notice-boards. This needs to be followed up with setting up of contact points and leaflets and brochures giving further information.

Personal selling

Face-to-face presentations to individuals and groups can be even more effective than in external marketing, because the presenter (manager, supervisor) has implicit authority behind what he or she is saying and is evident from the fact that face-to-face communication is regarded as having far greater impact than other communications methods9.

Incentives

It is clear from the notion of customer that employees must be offered some benefits in order to change their behaviour. The use of motivational incentives such as cash bonuses, awards, recognition programmes, prize draws and competitions directed at contact personnel in the services industry are very common. These can be used to overcome short-term resistance or to motivate employees toward consistent behaviour or to increase productivity.

Advertising

The use of mass media advertising (i.e. newspapers and television) to communicate with employees (in order to motivate them) is rare. It is only used in special circumstances such as strikes, where normal workplace methods of communications methods would be ineffective. This is because of the vast expense of these media and the fact that they are not narrowly targeted on a particular organization's employees. However, organizations need to take care of what image they are projecting of themselves and their workforce in their advertising aimed at external customers, as they are likely to be seen by their employees as well (see Exhibit 3.2). This can be turned into a positive advantage by portraying employees with positive customer-oriented attributes which employees can then attempt to emulate. An illustration of this is provided by the portrayal of enthusiastic and competent ‘Kwik Fit Fitters’ in Kwik Fit's advertisements on British television.

Exhibit 3.2. Aligning internal and external communications at Sainsbury's

In the autumn of 1998, Sainsbury's launched a major advertising campaign with the strapline ‘Value to shout about’. The ad campaign showed the actor John Cleese talking to shop staff (played by actors) about low prices and urging them to be more positive about Sainsbury's offer. One advert showed him dressed in a brash checked jacket bellowing through a megaphone into the ear of a hapless sales assistant urging her to be more upbeat about the value of Sainsbury's offer. In an another advert, Cleese is seen promising that Sainsbury's will refund twice the difference if a customer buys a can of baked beans cheaper elsewhere.

The campaign created by the advertising agency Abbott Mead Vickers BBDO appeared to signal a significant shift in Sainsbury's pricing strategy. Previous TV campaigns had positioned Sainsbury's as a more sophisticated, top end of the market food retailer. This was exemplified by a series of adverts in the early 1990s showing a number of well-known television celebrities making their favourite recipes with Sainsbury's ingredients conveying an air of indulgence. The new campaign had been launched in a response to a survey by A. C. Nielsen that had rated Sainsbury's top in choice, quality and service, but not price. The adverts were designed to challenge consumer perceptions that Sainsbury's was more expensive than its rivals.

The adverts did not go down well with the customers or the employees. The employees complained that the adverts made them look stupid. Sales figures also showed that the customers had also been turned off. Even worse, in a survey of television viewers, the adverts were voted the most irritating adverts on TV in 1998. Sainsbury's could have easily avoided the error of alienating its staff by testing the adverts internally before airing them. Sainsbury's also failed to prepare its employees for the apparent shift in its price positioning strategy. However, Sainsbury's reacted quickly in response to staff complaints by editing the advert and taking the emphasis away from the employee.

The following year, Sainsbury's did not make the same mistake when it launched its new marketing campaign ‘Making life taste better’, designed to switch emphasis back on to quality. This time, the advertising campaign was preceded by an internal marketing programme.

The programme was aimed at educating and motivating staff as part of an attempt to revive confidence in the Sainsbury's brand. The programme, called ‘One company, one agenda’, was devised by M. & C. Saatchi. It was launched at a special conference by the then Marketing Director to give it added credence.

The Sainsbury's campaign included:

![]() Posters placed at the back of shops and in corridors giving facts and figures about the changing customer using the strapline ‘When we understand our customers we can make all our lives taste better.’

Posters placed at the back of shops and in corridors giving facts and figures about the changing customer using the strapline ‘When we understand our customers we can make all our lives taste better.’

![]() An obligatory induction video for all new employees showing how every staff member contributes to the chain, from the distribution warehouse to the checkout, using the theme of a little girl waiting for food for her birthday party.

An obligatory induction video for all new employees showing how every staff member contributes to the chain, from the distribution warehouse to the checkout, using the theme of a little girl waiting for food for her birthday party.

![]() The staff magazine was revamped with the new store identity.

The staff magazine was revamped with the new store identity.

![]() Staff were also issued with company screen savers using the new ‘living orange’ logo and pictures of brightly coloured fruit.

Staff were also issued with company screen savers using the new ‘living orange’ logo and pictures of brightly coloured fruit.

The programme was a clear attempt to align internal communications with the external marketing campaign and to ensure that the brand promises were being delivered. The campaign was also designed to boost staff morale, as it coincided with the announcement of 1000 job losses. Sainsbury's main competitors, Tesco and Asda, already had successful staff motivation schemes and Wal-Mart, Asda's new owner, is well known for involving staff in company decisions.

Sources: Bainbridge, J. (1998). Are you marketing to your staff? Marketing, 8 October, pp. 20–21. Anonymous (1998). Cheesy John Cleese is top of the turn-offs. The Times, 18 December. Jardine, A. (1999). Sainsbury's motivating staff to revive image. Marketing, 17 June, p. 3. Witt, J. (2001). Are your staff and ads in tune? Marketing, 18 January, p. 21.

However, with the emergence of narrowcasting technology, organizations can now use live television to communicate with large numbers of employees simultaneously in diverse locations, in more targeted and costeffective ways. Traditionally, large multi-sited organizations have communicated with their disparate workforce through newsletters, corporate videos and annual conferences. These are very costly methods, particularly conferences, which in addition to hotel bills and travel time, take employees away from their workplace. This is why, recently, instead of holding its biannual review meeting for officers and directors in Memphis, Federal Express, which has the largest corporate television network in the world with 1200 sites able to receive transmissions, transmitted a live 3hour broadcast simultaneously to locations in the UK, Paris and Brussels, as well as the USA. All employees were able to watch the broadcast, with officers and directors participating in a phone-in session. The advantages of using such a medium for internal marketing are obvious.

Despite its potential, in the early 1990s only a handful of companies in the UK used business television and the market was worth only £3 million. In comparison, in the USA, the market for business television was estimated to be worth $350 million and estimated to be worth $1 billion by 1995. Business television was therefore predicted to be a growth area of employee communications because of the speed and reach of the medium10. However, with the widespread adoption of the Internet, business television is likely to be superseded by webcasting.

Place/distribution

Distribution refers to the place and the channels (or third parties) that are used to get products to customers. In the HRM context, place could mean meetings, conferences, etc. where policies are announced and channels could be used to refer to third parties (for example, consultants and training agencies) used to deliver training programmes.

Physical/tangible evidence

The physical evidence (also referred to as tangible evidence by some authors) refers to the environment in which a product is delivered and where interaction takes place between contact staff and customers, as well as any tangible goods that facilitate delivery or communication of the product. Physical evidence can be categorized as either essential or peripheral evidence. Peripheral evidence refers to tangible cues that a product has been delivered. Examples of peripheral evidence include such things as memos, guidelines, training manuals and so forth. Essential evidence, on the other hand, refers to the environment in which the product is delivered. In internal marketing situations, the environment in which the product is delivered is not as important as for services in general, because this will usually be the same as the normal work environment. However, special significance of particular policies may be signalled by holding conferences or by sending employees for special training to external agencies such as universities, for instance.

In contrast, tangible cues may be even more important in internal marketing than for the marketing of services in general. One of the more important tangible elements in internal marketing is documentation. Documentation of policies and changes in policies are important, because if employees are required to perform to certain standards then it is important that these standards are fully documented. Indeed, Quality Standards such as the British BS5750 and the International ISO 9000 put great emphasis on documentation in achieving quality. Other tangible elements may include training sessions to achieve required standards, for instance. The training sessions in themselves are a tangible manifestation of the commitment to the standards or particular policies.

Process

Process refers to how a ‘customer’ actually receives a product. In the internal marketing context, customer consciousness may be inculcated into employees by training (or retraining) staff. Structural changes such as the introduction of quality circles and new reporting methods may also be necessary. Process can also refer to whether new policies are introduced through negotiations with unions or imposed unilaterally. In the communications area, process can refer to the delivery method: for instance, whether circulars, videos or line managers are used to convey changes.

Participants

This refers both to people involved in delivering the product and those receiving the product who may influence the customer's perceptions. In an organizational context, communications need to be delivered by someone of the right level of authority if they are to be effective in achieving their implementation aims. Hence, in internal marketing the source of the internal marketing programmes plays a crucial role in their effectiveness. Employees in general tend to be influenced most by their immediate superiors11. One implication implicit in this is that inter-departmental or inter-functional communications are likely to be least effective. This is because they have equal status; that is, no direct authority to enforce compliance. Of greater importance is the implication that if the performance of contact staff is to be improved then the most effective means of communication is through their immediate superiors, who in turn need to be motivated by strategic management. Direct communication between strategic management and contact staff, although helpful, would not by itself be sufficient for the implementation of internal marketing programmes.

Market segmentation here is the process of grouping employees with similar characteristics and needs and wants. In services, for instance, employees may be grouped on the basis of whether they are contact employees or not. Other bases for segmentation might include type of benefits that employees want, and roles and functions that they perform. The existence of complex grading systems, departmental, functional and other organizational structures, suggests that the use of segmentation is already widespread in the HRM area. It is suggested, however, that employees need to be segmented along motivational lines rather than departmental or other lines traditionally used in HRM.

Market research involves identifying the needs and wants of employees and monitoring the impact of HRM policies on employees. This type of research has a long history in the HRM area in the form of employee attitude surveys. In the UK, for instance, employee attitude surveys date back to the 1930s, when the National Institute of Industrial Psychology started using them to study labour turnover, but nowadays are used for a wide range of issues, including attitudes held on supervision, remuneration, working conditions, specific personnel practices, incentive schemes and so forth. The number of companies that use these types of surveys are relatively small and are estimated to be around 8 per cent12. However, some companies attach great importance to them. IBM, for instance, has been using them since 1962. It has now computerized the process to make it even more effective. Obviously, these market survey type techniques are much more likely to be used by larger firms for reasons of cost effectiveness.

Employee surveys need to be handled with care, even more so than consumer surveys, because of employees’ fears of repercussions. Hence, it may be necessary to guarantee absolute confidentiality in order to ensure a good response. However, even if the response rates are high, the responses need to be interpreted carefully, as respondents are more likely to reply as they think the organization wishes them to respond rather than express their true views, because of the aforementioned fear of repercussions. Another important difference between employee and consumer surveys is that employee participation is not likely to be high if employees are not given feedback on the survey results. More importantly, management needs to show that action is taken over issues of concern uncovered by the surveys. Employees may also be suspicious of attitude surveys, as they have been used to weaken and deter unions13.

The foregoing analysis highlights the fact that it is possible to apply marketing techniques and concepts in order to create a motivated work-force working towards the implementation of corporate goals. Great care needs to taken, however, as to how these concepts and techniques are applied.

A multi-level model of internal marketing

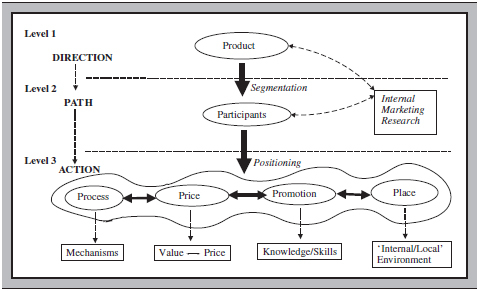

The model closely incorporates strategic elements by proposing a multilevel schema of how marketing tools and techniques can be used internally to generate commitment and effective implementation. Specifically, the model deploys six elements to constitute an internal marketing mix, as well as internal marketing research, internal segmentation, and positioning to operationalize the key parts of the model and stages. The combination of a multi-stage schema with a broader internal marketing mix provides a conceptualization able to highlight more clearly the role of segmentation and positioning in the internal context. By embedding the model within a strategic framework, it is also clearer in highlighting how implementation of strategy can be created.

The model is characterized by three strategic levels, namely Direction, Path and Action (see Figure 3.1). Level 1 is concerned with setting the general agenda of a particular mission or change, thus defining the direction in which organizational efforts are to be directed. This requires an evaluation of external opportunities and an understanding of organizational capabilities. Level 2, that of Path, requires specification of the route from the numerous alternative possibilities to achieve the set change or mission, which the organization opts to follow. Each of the alternatives needs to be examined closely. In particular, the types of barriers likely to be encountered and potential mechanisms for overcoming them need careful evaluation at this stage. The final level is that of Action. This requires a translation of a particular option into specific courses of action and activities. Detailed actions are necessary so as to make the undertaking as clear and trouble free as possible. The driving force at this level is dictated by decisions at level 2, which itself is defined by the direction set at level 1.

Figure 3.1 Multi-level model of internal marketing.

The interconnection between the strategic process and the internal marketing mix, marketing research, segmentation and positioning is depicted in Figure 3.1. The constituent activities of the internal marketing mix as defined by the internal context and how these relate to internal marketing research, segmentation and positioning are elaborated further in the discussion below.

Stage 1: Direction

At level 1 is the presence of the product element. In the internal context it is the product that sets direction. The product can be viewed as the definition and direction of change, which may simply be either in terms of changes in attitudes and behaviours of employees or in more tangible activities such as changed production activities or some other goal. Essentially, the product is any change in employee behaviour or attitudes that is required for the effective implementation of a particular corporate or functional strategy. In a strategic sense, the product dimension requires that the external environment and available opportunities are understood in relation to constraints upon the direction imposed by internal capabilities. Moreover, for true internal marketing to occur, the totality of the product package cannot solely be made up from a single vantage point, such as the owner/manager's viewpoint, but must incorporate aspects arising from the needs and requirements of employees. This is a necessary condition for efficient and effective implementation to occur. Two aspects of market research can be observed at this stage: external and internal research. External marketing research plays a role in identifying external opportunities and the changes necessary to take advantage of them, whereas internal marketing research, broadly speaking, can play a role in identifying capabilities and competencies through examination of the various sets of employees. Subsequently, this information can be fed into the process of specifying the ‘product’ for long-term success.

Stage 2: Path

Once a direction has been set by specifying the product, it leads onto the second level decision, namely that of Path. Here the general direction that has been taken needs to be broken into specific programme(s) that have to be delivered to particular groups of employees in order to achieve effective implementation. The Path level includes the Participants element, which examines ways of organizing individuals possessing particular needs against sets of organizational activities so as to facilitate the implementation process. At this level, the breakdown of the direction occurs, firstly by directing explicit attention to who (e.g. the individuals/Participants) is to be involved in the process of change and implementation, and secondly how they are to be involved. All participants, whether directly or indirectly involved, need to be explicitly defined in order to enhance effectiveness in the delivery process of the strategic change defined at level 1.

Internal segmentation

The next stage of the model's operationalization requires that internal marketing research is conducted so as to identify needs of the internal markets (e.g. employees). Numerous traditional marketing research techniques, ranging from simple surveys to indirect in-depth data collection techniques, can be usefully employed to capture a real sense of the motivations, potential fears and resistance of employees to the change programme. Once such needs and resistance have been explicated, then the next step is to examine the possibility of grouping these individuals upon their need requirements, as well as other characteristics such as demographics. Since a wealth of information, especially with respect to simple demographic information, is typically already resident in information stores such as personnel records, it can be easily complemented by further information, which may be of a psychographic nature. The first step in the internal segmentation process is to identify appropriate criteria for segmentation. It is important to note that extreme care needs to be exercised in the selection of segmentation criteria, since by definition these determine the usefulness and relevance of segments subsequently created. The second step is to apply the selected criteria to the relatively rich source of data to form segments.

The process of employee segmentation is necessary to identify whether participants form cohesive groups on the basis of some shared commonalties, by virtue of which it would be possible to create a specific package of activities that can then be directed at participant segments in order to facilitate implementation. The logic is that if specific needs and resistance can be associated with particular segments, then these needs and fears can be overcome by directing a specific package in a manner designed to satisfy employee needs and mediate their fears. As a process, this is much more effective than one that adopts a single approach for all employees, since neglecting employee differences diffuses implementation effort. Here, just as in external marketing research, a whole range of multivariate techniques such as clustering procedures, factor and conjoint analysis may be used to define needs and preferences in order to construct homogeneous groups (or segments). Moreover, given the relatively captive nature of the sampling population, it is possible to conduct depth and longitudinal studies with relative ease. At this stage, the whole process is strengthened if specific information with regard to resistance to change is explicitly incorporated into the process of grouping. This leads to a definition of homogeneous segments with regard to needs, resistances and actions required for a particular strategic course of action.

At this juncture, it is important to note that employee surveys need to be handled with care, even more so than consumer surveys, because of employees’ fear of repercussions. Hence, it may be necessary to guarantee absolute confidentiality in order to ensure valid responses. Additionally, high response rates can potentially be elicited by employing external independent organizations such as consultants to conduct the research. However, even if the response rates are high, the responses need to be interpreted carefully, as respondents are more likely to reply as they think the organization wishes them to respond rather than express their true views, because of the aforementioned fears. Another important difference between employee and consumer surveys is that employee participation is not likely to be high if employees are not given feedback on the survey results. Importantly, management needs to show that action is taken over issues of concern uncovered by the surveys.

Stage 3: Action

Once participant segmentation has been completed, then it is possible to start thinking about positioning and targeting identified segments through construction and appropriate leverage of the remaining elements of the internal mix, namely Process, Price, Promotion and Place (i.e. those occurring at level 3).

Internal positioning

In the external context, positioning requires selecting those associations that are to be built upon and emphasized, and those which are to be removed and de-emphasized. The situation is the same in the internal context. Internal positioning aims to create a tactical package of actions so as to overcome identified barriers, as well as fulfilling employee needs. This may at times involve focusing upon changing the importance that employees accord to a particular benefit and/or identifying and emphasizing benefits not previously recognized. Internal positioning involves providing an appropriate mix of differentiated benefits to a specific employee segment that will motivate it to achieve effective implementation of marketing and other strategies. Just as in external market positioning, internal positioning is segment specific and involves the leverage of the marketing mix elements, particularly those specified at level 3 of the model, in order to attain pre-specified goals. However, it is as well to note that, since all the elements of the internal marketing programme can potentially affect position, all the elements of the internal mix, not just those at level 3, are consistent and supportive. Internal positioning, due to the fact that it constitutes the specific actions necessary to facilitate implementation, acts as the focal point in the tactical development of an effective internal marketing programme.

The process of internal positioning also serves to highlight that there exist numerous possible alternatives to reach a given end. Each alternative must be assessed for its benefits relative to costs. Such an economic perspective helps to highlight two aspects, namely activity costs and the relative nature of the implementation concept. In other words, strategy implementation firstly requires planned execution of activities that incur costs and secondly its effectiveness depends on the appropriateness of these activities to the specific context. On the positive side of such an economic balance, costs will be far outweighed by the benefits if the right types of activities/actions are selected, i.e. there is a match between the actions and the organizational context. On the negative side, inappropriate activities constituting positioning are likely to yield few benefits, yet are likely to inflict significant sink costs, much like failed or poor positioning in the external context. This highlights the importance of careful selection and planned execution of internal marketing efforts. Ad hoc, half-hearted and poorly executed attempts at internal marketing are doomed to failure at the outset. To make internal marketing work requires a high level of commitment as well as time for the effects of its effort to materialize.

It is also necessary to appreciate that internal marketing outcomes are time dependent. It is likely in most instances that there is a time lag between undertaking internal marketing actions and affecting desired outcomes. This means, particularly in the case of implementing marketing strategies, that internal marketing programmes need to take place well before the launch of external marketing programmes. This is also of particular importance in considering the metrics of assessment, which are needed to capture pertinent facets of the change programme. This indicates the necessity to conduct longitudinal internal and external research in order for correct judgement to be made with regard to the effectiveness of internal marketing actions. Moreover, continuous monitoring serves not only to provide diagnostic information regarding implementation effectiveness, but also provides insights to carry forward into future actions and strategies.

Clearly then, analogous to the situation in external marketing, segmentation and positioning to the internal market (that is employees) are of critical importance. Poor internal segmentation and positioning, even with very clearly defined and precise tactical actions, leads to few, if any, productive positive results in the internal context. This perhaps accounts for the failure of many change programmes in which detailed breakdowns of activities are undertaken but with little regard for the needs of participants and/or a clear understanding of how these may either be achieved or contradicted by the processes used to achieve them in the first place. The oft-quoted statement in many reported cases of change, ‘the reward system did not encourage the change of activities’, is a rather appropriate illustration of poor understanding of, as well as the failure to match process activities to, the needs of employees in the change programme. By virtue of detailing internal segments and then bundling a specific package of process activities via positioning to meet the needs of employees it becomes possible to strive for employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction whilst simultaneously reaching out for organizational aims.

The internal marketing effort to position against internal segments leads onto the third level of the model. The third level, denoted by the term Action, requires the specification of precise actions directed at various identified segments of participants at level 2 through specific processes and systems. The delivery of such actions is captured by the remaining elements of the internal mix, namely Process, Price, Promotion and Place.

Process

The Process element is closely interlinked with the Participants element, in that it defines the context and mechanisms through which the Price, Promotion and Place elements are structured. It includes under its remit mechanisms and systems involved in the structuring of issues such as power, authority and resources14. Essentially, it defines the nature and manner of involvement, in order to deliver upon requisite duties and goals. Items such as whether meetings are to be held, where they are to be held and who is designated to run them are included here.

The Process element requires that decisions regarding the appropriate mechanisms for the ‘delivery’ of the package of actions to a specific segment are carefully evaluated. In other words, it requires designing an appropriate delivery format. The types of factors that need to be scrutinized, generally, are likely to be items such as ensuring that an appropriate organizational structure, group/team structure, reward systems, power and responsibility and leadership are set in place requisite to the ‘delivery’ that needs to be undertaken.

Price

The element of Price can be operationalized within an internal context by viewing price not simply as a cost to the employee (as depicted by terms such as opportunity cost, psychological cost, etc.), which is the traditional way of looking at price. We propose that it is better to view the Price dimension in the internal context as a balance between utility/value against cost to both the organization and the individual. This way of operationalizing Price is preferred, since it directs attention not only to what the costs to the employees are (psychological or otherwise) of the courses of the required actions of change, but also to the value/utility that can be derived from these changes by the individual employee and the organization. For instance, a change may incur cost (price on the part of the employee) in terms of having to work harder, do a different type of job and learn something new, but at the same time some utility/value may intrinsically be attendant with the new activities. The new task(s) may provide the opportunity to increase pay, access bonuses, provide a chance to excel and shine, and thereby build a route to career promotion, or through acquisition of new skills strengthen their bargaining hand in the job market. Thus, the Price element is useful in fine-tuning activities defined in the Process element by addressing both gains and losses to employees involved in the process of change.

Promotion

With respect to the Promotion element, operationalization in the internal context can be achieved by examination of how the range of promotional devices can be used to increase knowledge, skills and awareness of strategic change issues. Promotion activities, whether communications such as internal advertising or other internally directed promotional devices to elicit a response, can be used to aid the ‘buying into the programme’ process by employees. Promotion, in this sense, can be viewed as a skills and knowledge generation function. Internal communications, presentations and training via demonstrations (an external comparison of which can be things like point of sales demonstrations in industrial or retail selling) can all be used to raise awareness and skills, and thus sensitize employees to the activities required of them. Thus, promotion can be an extremely effective vehicle for letting the employees know what to do, when to do it and exactly how to do it, and thereby serves to clarify their role in the enactment of strategy.

Place

The last remaining element, Place, contains activities that can be thought to affect or be affected by the local environment of the organization. The Place element in the external context is concerned with distribution channels and reaching targeted customers; its focus is predominantly centred around the actual exchange and its environmental setting. In the internal context, Place can be taken to represent the visible and tangible, as well as invisible and intangible, aspects of work and the work environment. In other words, it represents the setting within which transactions/exchange between parties occurs, namely between the organization and its employees. Taken in totality, it captures more than the physical aspects of the environment; it includes cultural, symbolic and metaphoric aspects of the organization, from and within which setting employees form allegiance to the organization15. As such, Place can be used to further fine-tune aspects of the process, such as with whom power resides, what is the level of power within particular groups or segments of people, and how this needs to be altered and/or adapted to allow for effective strategy implementation. The external analogy that can be drawn here is the importance of having correctly co-ordinated and dovetailed channel strategies, through apt steering and co-ordination via channel captaincy, structure and power manipulation16.

The Place element can be used to draw attention to differences in culture and response arising from specific parts of the organization to the change programme. In fact, constituent activities of the Place element may be used to encourage certain types of behaviour, i.e. construct a culture change via mechanisms which alter the local environment by redistributing resources, power and responsibility away from some individuals to others more likely to champion the cause of change. This requires close scrutiny and understanding of current resources, work practices, the way the organization divides and factionalizes into groups and teams with their own identities and subcultures. Generally, we can say that the aim of the Place element is to attempt to devise an internal environment and atmosphere that is conducive to the achievement of particular goals. This may mean giving more resources, better support, changing or at least attempting to change and fine-tune organizational culture, as well as examining ways of empowering employees through structural and responsibility adjustments.

Relationship marketing and IM

The marketing mix reflects a marketing approach that is transaction based, that is, it is intended to maximize sales and profitability in the short term, and the marketing mix is used to influence consumer decision making and provide customer satisfaction. Direct contact with customers is minimal. Increasingly, however, the emphasis is away from transaction marketing and towards relationship marketing, which is regarded as more effective in today's environment.

Relationship marketing focuses not only on getting customers and generating transactions, but also on maintaining and enhancing relationships17. The emphasis is on continuous long-term relationships that lead to repeated market transaction, build loyalty and lead to profit- ability over the customer ‘lifetime’. Relationship marketing is an interactive approach to marketing. It relies on co-operation and trust rather than an adversarial approach. Building trust and commitment are crucial elements of relationship marketing. This requires delivering on promises and building financial, social and structural bonds between the firm and its customers. The relationship itself becomes the focus of marketing efforts rather than the product. In addition to the marketing mix variables, customer care/customer service initiatives and interactive marketing are central to relationship marketing. Key account management (or the designation of dedicated individuals or teams who deal specifically with key clients or accounts) is also central to developing and maintaining relationships with important customers. They are designed to foster co-operation and facilitate interaction so that the organization can respond quickly to the clients’ needs.

In the relationship marketing approach, a transaction-oriented approach to marketing heavily reliant on the traditional marketing mix approach is just a special case where simple or non-personal relationships are sufficient to satisfy customer needs. This applies to many low value consumer packaged goods, whereas for services, industrial goods and consumer durables, relationship marketing of different levels of complexity is appropriate.

Given its interactive nature and the importance of customer service, the success of relationship marketing strategies is critically dependent on attitudes, commitment and performance of employees. Hence, relationship marketing is highly dependent on an ongoing internal marketing programme for its successful implementation.

At the same time, given the long-term nature of employment, and the need for commitment and trust between employees and the organizations (or different departments, functions, etc.), the foregoing suggests that the relationship marketing approach and techniques are also appropriate for internal marketing. And, just as with external customers, the relationships per se and process are central to the building of relationships in internal marketing. Trust and commitment are also generated by delivering on promises. However, the marketing mix approach is likely to be more useful where a need for quick implementation is required, or high levels of employee turnover are common.

Barriers to implementation

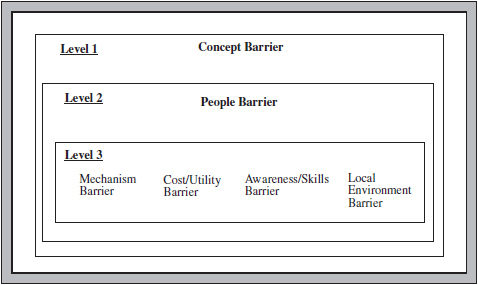

New strategies inevitably require behavioural and/or attitudinal changes on the part of employees, which can also lead to some degree of resistance and barriers to effective implementation. In recognition of this fact, we suggest that internal marketing involves a planned effort to overcome organizational resistance to change and to align, motivate and integrate employees towards the effective implementation of corporate and functional strategies. These barriers can be identified by examining resistance to change by each employee segment. The existence of such barriers leads to the emergence of implementation gaps, which have to be closed for effective strategy implementation to occur. We classify the range of barriers into the following gaps: concept, people, mechanism, cost/utility, awareness/skills and local environment (see Figure 3.2). Although the barriers could have been grouped in a number of ways, we have chosen the classification in a manner that highlights elements of the internal marketing mix likely to predominate in the removal of the identified gap.

The implementation barriers are nested to highlight interdependency. Moving from the outer (level 1) to the inner (level 3) level, the barriers move from being broad and strategic to being specific and tactical in nature. The level and nature of the barriers exemplify the types of actions necessary to remove them. For instance, any shortcomings in the change programme itself (that is, the conceptualization), because of its strategic nature and thus diffuse effects, may lead to contradictions at levels 2 and 3 or fail to produce the desired outcomes in terms of marketplace success. In other words, problems at this level can, and often do, cascade downwards and outwards into the marketplace. We observe that flaws at this level lead to two types of error, which we will refer to as Type I and Type II. Type I errors are those in which incorrect strategic actions are effectively implemented and the outcome is that expected marketplace performance either fails to materialize or even declines. Type II errors are those in which the conceptualization fails to fully/adequately take into account the internal context and needs of various stakeholders, thereby creating internal contradictions and conflicts. These in turn manifest themselves by creating a certain level of organizational dysfunction and can lead to the appearance of implementation gaps at any one or even all the levels. If the shortcoming originates from level 2, for example in the way the segments were formed, then there will be ramifications at level 3, since it is likely that wrongly directed actions and activities will be set in place, i.e. relatively poor implementation is likely to follow. Instances of relatively poor implementation, even if the product conceptualization is appropriate to the specific context, we call Type III errors. Once again, we would observe that the problems at this level would cascade downward into level 3 actions. Problems originating at level 3 have a narrower effect in that no downward cascade exists. However, since each of the internal mix elements is interlinked, there are horizontal effects of one barrier leading to or compounding problems in another. Moreover, the interlinkage of the internal mix elements also indicates that it is not possible to preclude upward ripple effects. For instance, local environment changes involving adaptations at a broad level, such as attempting to modify organizational culture, have pervasive effects with important ramifications at the strategic product conceptualization level.

Figure 3.2 Barriers to implementation: a nested approach.

Finally, working through the three stages leads on to further diagnostic research that feeds back into the product, thus acting as a homeostatic monitoring mechanism, as well as creating cybernetic closure.

Case illustration of the multilevel internal marketing model

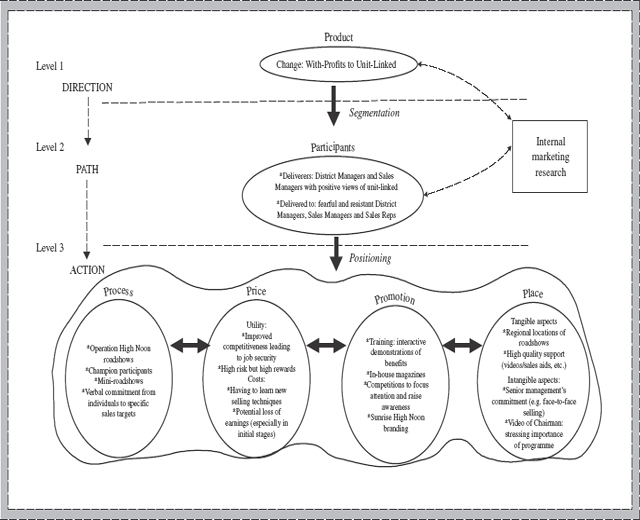

We use here a case to illustrate how the multi-level model of internal marketing can practically be used to direct attention to pertinent issues in the implementation of a change programme. The case is based on how Pearl Assurance dealt with the problem of changing the business mix of its products in face of opposition from some of its sales force. The case is an illustration of the model in directing managers’ attention to factors that need to be addressed in generating effective implementation. The case information presented is based upon primary information as well as secondary sources.

Changing the business mix at Pearl Assurance

The background

In 1990, Pearl Assurance (PA) was acquired by Australia Mutual Provident (AMP). Until then, PA specialized in selling life assurance based on ‘with-profits’ policies. These policies guarantee to pay out a minimum sum assured on maturity of the policy or the death of the policyholder. The profits or bonuses are a share of the surplus that the company may make in excess of the guaranteed payout, as a result of its investments. These policies, also known as endowments, came into great demand in the late 1980s as a result of rising popularity of endowment mortgages in the housing market. A major disadvantage of the ‘withprofits’ product is that in order to provide these guaranteed payouts a substantial amount of the company's capital is tied up in reserves. However, this period also saw the development of ‘unit-linked’ products whose performance is tied to that of the stock market. With unit-linked products, policyholders are allocated a number of units in a life insurance fund, the value of which is published daily. In addition, AMP's experience in Australia had shown unit-linked products to be more profitable whilst tying up less capital in reserves. Hence, a decision was made to move the balance of products to be sold in favour of unit-linked business.

However, PA encountered opposition from its sales force when it attempted to pursue this policy. There were several reasons for this opposition. Firstly, the sales force had been ‘turned off’ unit-linked policies since the October 1987 stock market crash, which had graphically illustrated the high potential risks. Secondly, many of the sales force and the backroom staff were unfamiliar with unit-linked products. Moreover, the change in the policy was perceived to be as a direct consequence of change in ownership, which occurred with the AMP acquisition of PA, rather than a market-driven necessity.

Life assurance is a product that the majority of customers know very little about, as it is a complex and infrequently purchased product. The benefits of life assurance are such that they cannot be fully evaluated without first purchasing the product and then awaiting for the policy to reach maturity. Hence, sales personnel play a crucial role in the choice of products (that customers make), since customers are unlikely to be fully aware of the types of products available and their relative merit. Customers thus rely heavily on the advice of salespeople, who are regarded as experts. It was essential, therefore, that PA get its sales force behind the new policy.

Pearl Assurance has around 5000 salespeople, who are geographically dispersed across the UK. PA sensed resistance to the new policy was likely and took a decision to implement the change through the use of roadshows. The first roadshow, called Operation Sunrise, was used to highlight the benefits of all forms of equity-linked investments. Although effective in raising awareness of the market for unit-linked products, the increase in sales of these products was less than expected. What follows is an account of Operation High Noon, which was launched in October 1992, illustrated in a manner designed to highlight the practical role of the internal marketing model in directing attention to activities and actions necessary for effective implementation.

Product

The product in this case was the requirement to shift the emphasis of business away from with-profits policies towards unit-linked products (see Figure 3.3). The benefit of doing this was that unit-linked policies were a growth market. Moreover, unit-linked policies also had advantages for customers compared to with-profits, in that they were more flexible and allowed a reduction in the need to keep capital reserves, which could then be used to increase benefits to the customers and/or the organization. The executive believed that adoption of the policy would help PA increase competitiveness, improve performance and hence improve job security for everyone.

Market research

Before launching Operation High Noon, PA commissioned independent research on the attitudes of the salespeople to unit-linked policies. Interviews were conducted in two of the best and two of the worst performing divisions in terms of unit-linked policy sales. All grades of management were included as well as the sales force. Based on their attitudes to unit-linked and with-profits, respondents were classified as ‘for’ or ‘against’ change. This illustrates one way of segmenting ‘the market’ in an internal context.

We can see that, on the basis of information received from internal research, two segments appeared to emerge: an ‘Enthusiastic’ segment and a ‘Resistant’ segment. Investigation of the two segments highlighted that individuals for change tended to be enthusiastic managers and aspiring sales representatives. Those against change tended to be managers unwilling to impose change on those resisting the change and included among them many unambitious sales staff. The internal research also identified that those resisting change tended to be pre-1987 staff, who had received complaints from customers after the 1987 stock market crash, whereas the segment with a more favourable attitude (Enthusiastic segment) consisted predominantly of newer (post-1990) recruits. The logic of segmentation would indicate that different stratagems would be required to effect implementation because of differences in orientation of each segment. These differences in segment orientation were likely to manifest themselves in producing different gaps/barriers to the process of strategy implementation.

Participants

Participants in the process, as indicated in the above discussion, were identified to be two groups/segments with differing orientations. From the Enthusiastic segment, key individuals were selected on the basis of

Figure 3.3 Case illustration of the multi-level model of internal marketing.

their enthusiasm and knowledge to run the Operation High Noon roadshows. These participants included both managers and sales representatives in order to ensure, and at the very least to convey an impression, that everybody's opinion was being taken into account. In other words, individuals from this segment of employees were used to drive the change to unit-linked policies (i.e. they were responsible for delivery).

Once created, the roadshows were targeted at District Managers, Sales Managers and Sales Representatives. Although all managers and representatives were included, the shows were particularly targeted at the more resistant segment of the audience. The process of segmentation was, in fact, carried one stage further, by forming sub-segments on a functional basis. And, in line with the logic of segmentation, separate seminars were designed for each of three different sub-segment groups (District Managers, Sales Mangers and Sales Representatives), with specifically targeted messages to each. On completion of internal segmentation, the next step is to move on to the third stage, which involves leverage of positioning actions and activities to facilitate tactical implementation.

Process

The mechanism through which the change was to be enacted (i.e. the Process) was the roadshow. Within this process, separate seminars were designed for delivery to different groups of people with different sets of needs. In fact, as noted above, segmentation was carried one stage further so as to create sub-segments of the initial Enthusiastic and Resistant segments on the basis of functional difference. This was deemed necessary because the functional category was considered an important parameter in defining segment needs.

The roadshows were used as a vehicle to explain the rationale behind unit-linked policies on a face-to-face basis by selected ‘enthusiastic’ managers. The enthusiastic managers themselves were provided with training for this purpose. The roadshow managers used these opportunities to point out that with-profits policies required PA to put aside capital reserves which could not be invested in the open market. Unit-linked products, on the other hand, free these reserves to be invested in the open market and thus serve their customers better than with-profits policies. The advantages of flexibility for customers of unit-linked policies were also highlighted, particularly the fact that they could alter options with their circumstances, without having to surrender their policies or drawing up new contracts, which either caused clients to be unhappy, because of losses incurred, or being levied extra charges, respectively. To reassure those representatives who were worried that the volatility of the stock market would lead to losses, it was pointed out that unit trusts were very safe because the risk was spread over numerous shares. It was further demonstrated that, whilst the stock market fluctuated in the short term, on a 15or 20-year time horizon unit-linked policies outperformed with-profits policies. Another point made was that, due to an increased customer awareness of the advantages of unit-linked policies, there was a trend away from endowments towards unit-linked policies. Financial press reports were used to provide independent evidence of this.

At the sub-segment level, seminars were specifically developed to target and train particular audiences; seminars for District Managers were used to develop business plans in order to achieve targets set for unit-linked policies, seminars for Sales Managers were designed to help them motivate their sales representatives, and seminars for the sales representatives illustrated new sales techniques for unit-linked products. Moreover, in order to maintain momentum, each District Manager was asked to organize a mini-roadshow for his or her district. Within this process, each delegate was asked to state in writing how they would assign extra resources to achieve their unit-linked goals. For instance, Divisional Managers were asked, as a minimum, to give a verbal commitment of targets that they would set for their districts and how these would be achieved.

Price

The internal marketing operationalization here calls for an understanding of the costs incurred and the utility/value that is to be gained by the participants in each segment. Firstly, we consider the costs dimension. The fact was that unit-linked products were substantially different from with-profits policies and thus required time and effort, on the part of the sales representatives, to learn new selling techniques. This was additional to the psychological costs of change. Secondly, since the unit-linked products were new to them, it was possible that the sales representatives could suffer a potential loss of commissions. Furthermore, there was also a greater element of risk associated with unit-linked policies than with-profits policies. Thus, in order to convince the participants within each segment of the advantages of the change, it was necessary firstly to understand and secondly communicate effectively to each participant the value of the changeover. Facts, such as the unit-linked market being a rapidly growing market and that PA were getting into it early, and that the prospects for high commissions were good, needed to be stressed in order to overcome resistance. This was particularly relevant for the Resistant segment. Participants from the Enthusiastic segment selected for driving the roadshows were motivated by the prospect of promotion, if their efforts proved to be successful. Other benefits stressed were that involvement with unit-linked products would enhance and extend their skills. This would allow them not only to provide a better service to their customers, but would also boost future employment prospects.

Promotion

The promotion tool was used extensively to raise awareness, as well as build competence and confidence of the sales force in unit-linked policies. The initial mechanism to impart information and build skills was the roadshow demonstrations. This constituted a face-to-face communication, which capitalized on the advantages of an interactive medium to clarify and advance the cause of the change programme, as well as providing further opportunity to understand employee fears and resistance. Numerous other promotional techniques were used in addition to such face-to-face communications (or personal selling) by managers and senior staff to the sales force. For instance, in-house magazines were used to explain the rationale behind the changes, and competitions to incentivize individuals and rapidly heighten interest and awareness. Videos were also used at the roadshow, one of which featured the Chairman of PA to emphasize that the policy change had director level support for it. Another video showed sales managers overcoming objections to unitlinked policies. Further to this, in order to concentrate effort and focus the range of events, the roadshows were also ‘branded’ ( the first roadshow was ‘Sunrise’ and the second ‘High Noon’).

An interesting point to emerge, with regard to who should actually be responsible for internal marketing, from the High Noon roadshow was that the marketing department had to take a less prominent role in the roadshows. Only then were the actions of change perceived to be acceptable to the sales force, who otherwise had been inclined to see it simply as a new sales gimmick from the marketing department. In fact, it was felt that the previous roadshow (Sunrise) had not been as successful as it could have been, because the thrust of all the literature had all originated from the marketing department. This indicates that a broader and more crosssectional involvement is required in the use of internal marketing.

Place

As the sales force was widely dispersed geographically, the venues chosen were based on the regional locations of the sales force and roadshows were tailored to match each situation. Place in the internal marketing mix refers not only to the locations where products are provided to customers, but also other tangible and intangible aspects required to effectively carry out the task, such as back-up support material and personnel.

In this respect, the videos and high quality sales aids provided tangible evidence of the commitment of the organization to the change initiative. An example of one of these high quality sales aids was The ABC Risk/Reward Presenter (where ABC stood for the Adventurous, Balanced and Cautious investor). The presenter illustrated how unit-linked products could be tailored for customers with different risk profiles, a feature not offered to with-profits customers. For instance, the adventurous customer could be sold a unit-linked product which had a high risk attached but had high potential rewards. The availability of the high quality support material and the associated training reduced the effort required from the sales force to change and therefore speeded up the support and acceptance of the unit-linked product. The sales literature was further supported by copies of speeches and overhead slides to act as a reminder and reinforcement of the principal message.

The second dimension of the Place element that requires attention is the role of intangible aspects in the implementation process. It is clearly necessary to examine the appropriateness of the organizational environment to the process of change, and if necessary amend it by effecting an appropriate cultural climate through transmission of appropriate cues. For example, the video featuring the Chairman emphasized the importance as well as the high level of commitment to the change programme. Without doubt, symbolic actions and metaphoric examples need to be carefully examined for their potential use in internal marketing. Regular exhortations as well as compliments on work well done were other simple devices to create and maintain a positive attitude to the programme.

Results

The degree of success of the programme of events can be ascertained from the fact that the Pearl Assurance 1993 Annual Report announced that whilst unit-linked business accounted for only 5 per cent in 1991, it had grown to 30 per cent by the end of 1993. The major problems encountered in this campaign were to maintain the momentum that was built up by the roadshows. The necessity of involving staff at different levels in the hierarchy led to a complicated cascading process of communication during the roadshows.

Summary

The purpose of this chapter has been to demonstrate how and to what extent marketing techniques such as segmentation, market research and the marketing mix can be used for developing customer-oriented behaviour and generally motivating employees.

The chapter began with a discussion of how the different elements of the traditional 4Ps marketing mix and the extended 7Ps services marketing can be applied to internal marketing. Application of segmentation and market research techniques are also discussed. This is followed by the elaboration of a multi-stage model which highlights how a marketing-like approach and techniques can be used internal to the organization. By expounding the concept of an internal marketing mix, internal market research, and the critical role of internal segmentation and internal positioning, we have advanced the notion that many of the concepts and frameworks which are critical in creating external marketplace success can be usefully employed, indeed need to be employed, albeit adapted to the internal context, to aid the process of strategy implementation. The model also serves to highlight the importance of an internal focus to complement an external marketplace focus. Without an effective internal focus capable of interlinking with an external focus, many potentially successful strategic visions are likely to remain just that: visions.

Another point of interest to emerge, particularly from case evidence, that needs to be highlighted is that the marketing department should not solely be charged with the responsibility of running internal marketing programmes. The dominance of a single functional department will have a tendency to lead to, in reality or simply in perception, to a sense of functional/departmental bias. The imposition, perceived or otherwise, of such a unitarist viewpoint is likely to create strong resistance. This strongly indicates the need to use cross-functional teams or task forces in the development and running of internal marketing programmes.

References

1. Kotler, P. (1972). A generic concept of marketing. Journal of Marketing, 36 (April), 346–54.

2. Sasser, W. E. and Arbeit, S. F. (1976). Selling jobs in the service sector. Business Horizons, June, 61–2.

3. Sambrook, S. (2001). HRD as an emergent and negotiated evolution: an ethnographic case study in the British National Health Service. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 12(2), 169–93.

4. Carson, K. D., Carson P. P., Yallapragada, R. and Roe, C. W. (2001). Teamwork or interdepartmental cooperation: which is more important in the health care setting? The Health Care Manager, 19 (4), 39–46.

5. See Carson et al. above.

6. See, for instance, Piercy, N. and Morgan, N. (1991). Internal marketing: the missing half of the marketing programme. Long Range Planning, 24 (2), 82– 93. Barnes, J. G. (1989). The role of internal marketing: if the staff won't buy it why should the customer? Irish Marketing Review, 4 (2), 11–21.

7. Booms, B. H. and Bitner, M. J. (1981). Marketing strategies and organisation structures for the service firms. In Marketing of Services (J. H. Donnelly and W. R. George, eds). Chicago: American Marketing Association, pp. 47–51.