chapter six

Total quality management

(TQM) and internal

marketing

Introduction

The rapid market share gains in world markets by far eastern competitors prompted many to examine how nations such as Japan have managed to build their success. The Japanese, over time, have come to represent a standard against which to measure manufacturing excellence. One of the most prominently mentioned issues in Japan's success is quality management.

Surviving in the new world of intense competition, companies have had to establish strategies that can cope with the turbulent changes in the environment. In this world, adding value is the hard work, but it is merely the entry-ticket in the battle for survival. Many companies spend their time figuring out how to provide high quality at low cost. But so do their competitors. This is the dynamic of competition. If others can mimic what you do, then what you do sums up to little differentiation value. The game-play of competition quickly erodes competitive advantage. To sustain competitive advantage, companies must build strong foundations that will not be blown away in competitive storms. This is not achievable over the long term, as the recent collapse of dotcoms illustrated, through a focus on hype and ceremony built by advertising and promotions. Rather, it requires organizational capabilities and competencies built on sound internal foundations. The foundations of competence are more important than short-term gains. Changes in the business environment can quickly alter cost structures, technologies and consumer preferences, but properly managed competencies can last a lifetime. Total quality management (TQM) in the modern world has become part of the fabric for organizational competence.

Total quality management successes

The use of TQM has, since the 1980s, become widespread. For instance, one survey found that 74 per cent of firms practise TQM1. Another survey found that 78 per cent of Fortune 1000 organizations plan to increase their use of TQM, while only 5 per cent plan to decrease their use of TQM2. There is also evidence that TQM positively impacts organizational performance, when practised correctly3.

There are many success stories of how TQM has helped transform companies. For example:

![]() Ericsson Inc. of Lynchburg, Virginia, implemented a successful TQM programme. The TQM programme, named Winshare, saved the company approximately US $60 million over 10 years. Employees were divided into 63 teams, and each team elected a coworker as a leader. Teams were used to develop improvement ideas and received US $6000 to implement them4.

Ericsson Inc. of Lynchburg, Virginia, implemented a successful TQM programme. The TQM programme, named Winshare, saved the company approximately US $60 million over 10 years. Employees were divided into 63 teams, and each team elected a coworker as a leader. Teams were used to develop improvement ideas and received US $6000 to implement them4.

![]() AT&T Wireless Services used TQM to transform its call centre. The call centre, based in Austin, Texas, was growing in business volume by 40–50 per cent. This surge in service calls caused adecline in the quality of customer service, as well as employee development and training. Employee turnover rate rose to 25 per cent due to vague goals and expectations. Deploying TQM techniques, the company tackled the problem by installing a PCbased monitoring system and hiring extra personnel to help improve the process. With the PC system, calls could be stored during specific time periods and could be accessed from any touch-tone phone. Two call-quality monitors were hired to ease the load on supervisors and allow them to concentrate on other duties. Management implemented a grading system that directly linked performance with rewards and promotions. Individualized training resulted from the automation process, as employees began to review some of their own calls. The results led to an increase in employee performance, training and a better understanding of how pay is linked to performance. Employee turnover rate dropped to 11.0 per cent in 1995, showing that TQM worked for AT&T's call centre5.

AT&T Wireless Services used TQM to transform its call centre. The call centre, based in Austin, Texas, was growing in business volume by 40–50 per cent. This surge in service calls caused adecline in the quality of customer service, as well as employee development and training. Employee turnover rate rose to 25 per cent due to vague goals and expectations. Deploying TQM techniques, the company tackled the problem by installing a PCbased monitoring system and hiring extra personnel to help improve the process. With the PC system, calls could be stored during specific time periods and could be accessed from any touch-tone phone. Two call-quality monitors were hired to ease the load on supervisors and allow them to concentrate on other duties. Management implemented a grading system that directly linked performance with rewards and promotions. Individualized training resulted from the automation process, as employees began to review some of their own calls. The results led to an increase in employee performance, training and a better understanding of how pay is linked to performance. Employee turnover rate dropped to 11.0 per cent in 1995, showing that TQM worked for AT&T's call centre5.

![]() Champion International Corporation's paper and wood pulp products plant operations were transformed through TQM. Total quality management enabled employees to break down compartmentalized departments into cross-functional teams to solve problems. Champion found that when personal satisfaction, derived from its quality efforts, increased it led to improvements in product consistency and reliability6.

Champion International Corporation's paper and wood pulp products plant operations were transformed through TQM. Total quality management enabled employees to break down compartmentalized departments into cross-functional teams to solve problems. Champion found that when personal satisfaction, derived from its quality efforts, increased it led to improvements in product consistency and reliability6.

Many other companies, such as Xerox, Motorola, DuPont, Ford and General Motors, have used a range of TQM tools and methodologies, such as benchmarking, to improve product quality and operational efficiency. These improvements resulting from TQM have been real and significant. The question then is: what is TQM? And, how can the best results be derived from it?

Total quality management: the modern paradigm of organizational success

There are probably as many definitions of quality as there are writers. The notion of quality is as old as trade and exchange itself. In the modern day, quality is fundamentally about delivering customer satisfaction. According to quality guru W. E. Deming, competitiveness comes from delivering customer satisfaction, which is created by being responsive to the customer's views and needs, and constantly improving the fulfilment of these through continuous improvement of the product and service. The fundamental touchstone of the quality philosophy is fulfilling customer requirement7.

Another quality guru, Ishikawa8, suggests that quality means quality of:

![]() Work;

Work;

![]() Service;

Service;

![]() System;

System;

![]() Information;

Information;

![]() People;

People;

![]() Process; and

Process; and

![]() Objectives.

Objectives.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), in its ISO 8402 charter, provides a series of quality definitions. According to the ISO 8402, quality is the totality of features and characteristics of a product or service that bear on its ability to satisfy stated or implied needs. Within this philosophy, quality control is an important function to ensure the fulfilment of given customer requirements. Ishikawa9 states that quality control is carried out for the purpose of realizing the quality that conforms to customer requirements.

Total quality management derives from a business philosophy that focuses on customer satisfaction. It works through the integration and co-ordination of all activities in an organization, as well as on the continuous improvement of all activities in that organization. According to Deming10, TQM is founded on three basic principles:

![]() empowered employees;

empowered employees;

![]() continuous quality improvement; and

continuous quality improvement; and

![]() quality improvement teams.

quality improvement teams.

Total quality management involves designing organizations such that they are able to please customers day in, day out. Quality proposes two points of focus:

![]() careful design of the product or service;

careful design of the product or service;

![]() ensuring that the organization's systems can consistently produce the design.

ensuring that the organization's systems can consistently produce the design.

These objectives can only be achieved if the whole organization is orientated towards them. Oakland11 emphasizes the importance of integration and involvement, stating that:

‘. . . everyone in the organization, from top to bottom, from offices to technical service, from headquarters to local sites, must play their part.’

Product and service quality improvement is an essential and critical aspect of TQM, and quality is only that which holds value for the customers who are using the products or services12. Therefore, an organization must be able to identify the customer's needs, wishes and expectations. This means that a manager has to instil the idea of customer-driven quality throughout the organization and manage all employees in the different departments/functions so that there will be continuous improvement in quality.

Total quality management focuses externally on meeting customer requirements exactly, while internally it is driven by management commitment, employee training and education. The main objective of TQM programmes is to embed quality into processes, and thus into products and services. Total quality management stresses the involvement of every-one inside an organization and related persons outside the organization, such as customers and suppliers. Total quality management uses statistical techniques such as statistical process control (SPC) and pragmatic tools such as the Cause and Effect Fishbone to ensure improvement in the firm's quality. However, TQM entails much more than statistical tools. It requires top management commitment, leadership, training and teamwork. These are the key factors in a successful implementation of TQM. As Tobin13 correctly notes, TQM is not mere techniques, it ‘is the totally integrated effort for gaining competitive advantage by continuously improving every facet of organization culture’.

Total quality management principles

Total quality management in essence comprises of a set of quality principles and values that serve to build an organizational structure that supports effective quality improvement initiatives. These principles guide the development and implementation of quality concepts, tools and practices. For quality to get a foothold, it must be fully integrated into the managerial system of the company. Without integration with the mainstream managerial system quality programmes soon begin to lose energy and fade, and often fail to last long enough to produce significant improvements.

There are several individuals (Deming, Juran, Crosby, Feigenbaum), who have commented upon the general philosophy of TQM14. From these, several principles can be drawn:

![]() TQM starts at the top. In order to succeed, TQM must be part of a company's overall business strategy. An essential factor here is that absolute commitment by top management is a must. Additionally, this commitment has to be transparent to the whole company through adequate support and continuous monitoring.

TQM starts at the top. In order to succeed, TQM must be part of a company's overall business strategy. An essential factor here is that absolute commitment by top management is a must. Additionally, this commitment has to be transparent to the whole company through adequate support and continuous monitoring.

![]() TQM focuses on the customer. Quality is based on the concept that everyone has a customer, and that the requirements, needs and expectations of all customers must be met every time. Therefore, both internal and external customers are important and should be the centre of attention.

TQM focuses on the customer. Quality is based on the concept that everyone has a customer, and that the requirements, needs and expectations of all customers must be met every time. Therefore, both internal and external customers are important and should be the centre of attention.

![]() TQM is process based. Total quality management is basically a customer-oriented paradigm that occurs through processes. The emphasis on customer focus requires a company to be process based. A process organization is simply one that is conceived as a flow of interdependent processes, which must be understood and improved. Steward15 notes:

TQM is process based. Total quality management is basically a customer-oriented paradigm that occurs through processes. The emphasis on customer focus requires a company to be process based. A process organization is simply one that is conceived as a flow of interdependent processes, which must be understood and improved. Steward15 notes:

‘In the future, executive positions will not be defined in terms of collections of people like head of sales department, but in terms of process, like senior-VP-of-getting-stuff-to-customers, which is sales, shipping, billing. You'll no longer have a box on an organization chart. You'll own part of a process map.’

Scholtes and Hacquebord16 explain how structural configuration shapes employee priorities on the job as follows:

‘If you ask someone in your work,‘‘who is important for you to please?’’ and if he or she answers ‘‘my boss’’, that person experiences the organisation as a chain of command. If the answer is ‘‘the person in the next process, my internal customer’’, that person has a systems perspective.’

Numerous process improvement frameworks and methodologies have been developed, such as the Taguchi methods17 and quality function deployment18. Complementing these are radical improvement methodologies such as Business Process Re-engineering.

![]() TQM uses teams. Employee teams are part of the ‘motivational glue’ within TQM. Total quality management uses teams as a basic building block in its effort for continuous improvement. A wide range of teams have been utilized within TQM, from quality circles to self-managed autonomous teams. Collaboration in teams is a fundamental necessity for TQM capability.

TQM uses teams. Employee teams are part of the ‘motivational glue’ within TQM. Total quality management uses teams as a basic building block in its effort for continuous improvement. A wide range of teams have been utilized within TQM, from quality circles to self-managed autonomous teams. Collaboration in teams is a fundamental necessity for TQM capability.

Team building is one of the key tasks demanded of leadership in a TQM organization. Indeed, process organization needs almost by definition to be run cross-functionally. Cross-functional teams work because they bring together people with different expertise who might never cross paths in a function-led organization, although their work might be highly interdependent.

![]() TQM requires training for everybody. Quality is built through the skills of the employees and their understanding of what is required. Educating and training provides employees with the information of what they need to do and informs them about the strategy and direction of the organization. Training builds the skills they need to secure quality improvement.

TQM requires training for everybody. Quality is built through the skills of the employees and their understanding of what is required. Educating and training provides employees with the information of what they need to do and informs them about the strategy and direction of the organization. Training builds the skills they need to secure quality improvement.

![]() TQM uses tools to measure and follow progress. In TQM culture there is an emphasis toward ‘what gets measured gets done’. Measurement and feedback are the basis for improvement activities.

TQM uses tools to measure and follow progress. In TQM culture there is an emphasis toward ‘what gets measured gets done’. Measurement and feedback are the basis for improvement activities.

![]() TQM requires continuous improvement. The concept of continuous improvement is built on the premise that ‘work’ is the result of a series of interrelated steps and activities that result in an output. Continuous attention to each of these steps in the work process is necessary to improve the reliability of the process and, hence, the output quality.

TQM requires continuous improvement. The concept of continuous improvement is built on the premise that ‘work’ is the result of a series of interrelated steps and activities that result in an output. Continuous attention to each of these steps in the work process is necessary to improve the reliability of the process and, hence, the output quality.

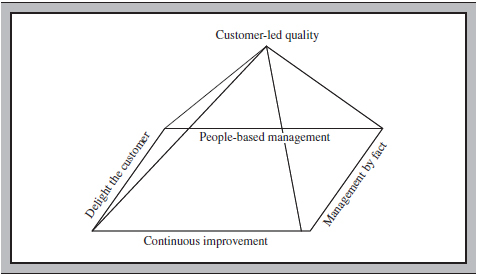

Kanji19 proposes a pyramid model of Quality Management, which is based on the proposition that to achieve a high customer satisfaction level (delight the customer), the organization has to improve continuously all aspects of its operation (continuous improvement). This needs leadership to make decisions on objective evidence of what is actually happening (management by fact), through involvement of all employees in quality improvement activities (people-based management), leading ultimately to business excellence. Kanji's model is made up of four principles: delight the customer; management by fact, people-based management and continuous improvement (see Figure 6.1).

![]() Delight the customer. Delight means being best at what matters most to customers, and this changes over time. Understanding these changes and delighting the customer now and in the future is an integral part of TQM.

Delight the customer. Delight means being best at what matters most to customers, and this changes over time. Understanding these changes and delighting the customer now and in the future is an integral part of TQM.

![]() People-based management. Knowing what to do, how to do it and getting feedback on performance is one way of encouraging people to take responsibility for the quality of their work. Involvement and commitment to customer satisfaction are ways to generate this.

People-based management. Knowing what to do, how to do it and getting feedback on performance is one way of encouraging people to take responsibility for the quality of their work. Involvement and commitment to customer satisfaction are ways to generate this.

![]() Continuous improvement. Continuous improvement or incremental change, not major breakthroughs, is the aim of all who wish to move towards total quality.

Continuous improvement. Continuous improvement or incremental change, not major breakthroughs, is the aim of all who wish to move towards total quality.

Figure 6.1 Total quality management. Source: adapted from Kanji, G. K. (1996). Implementation and pitfalls of quality management. Total Quality Management, 7, 331–43.

![]() Management by fact. Knowing the current performance levels of the products or services in the customers’ hands and of all employees is the first stage of being able to improve. Management must have the facts necessary to manage business at all levels. Giving that information to people so that decisions are based upon facts rather than ‘gut feelings’ is essential to continuous improvement.

Management by fact. Knowing the current performance levels of the products or services in the customers’ hands and of all employees is the first stage of being able to improve. Management must have the facts necessary to manage business at all levels. Giving that information to people so that decisions are based upon facts rather than ‘gut feelings’ is essential to continuous improvement.

Leadership features as a prime mover in this model. It is through leadership effort that all the principles and core concepts are resourced and communicated for business excellence. The development and implementation of quality strategies require fundamental changes in corporate culture and organizational behaviour and therefore can only be achieved through active leadership from top management. The biggest role of leadership is to motivate people.

Each of the above principles is subdivided into two core concepts, namely customer satisfaction and internal customers are real; all work is process and measurement based; teamwork and people make quality; continuous improvement cycle and prevention (Figure 6.1).

Delight the customer

![]() Customer satisfaction. Companies must uncover what is important for their customers and measure their own performance against customer targets.

Customer satisfaction. Companies must uncover what is important for their customers and measure their own performance against customer targets.

![]() Internal customers are real. The definition of quality (i.e. satisfying agreed customer requirements) relates to internal as well as external customers. This is encapsulated in the customer/supplier chain and highlights the need to get internal relationships working in order to satisfy the external customer. Whether it is supplying information, products or a service, the people you supply internally depend on their internal suppliers for quality work.

Internal customers are real. The definition of quality (i.e. satisfying agreed customer requirements) relates to internal as well as external customers. This is encapsulated in the customer/supplier chain and highlights the need to get internal relationships working in order to satisfy the external customer. Whether it is supplying information, products or a service, the people you supply internally depend on their internal suppliers for quality work.

Management by fact

![]() All work is process. A process is a combination of methods, materials, manpower, machinery, activities, etc. which, taken together, produce a product or service. All processes contain inherent variability. The approach in quality improvement is progressively to reduce variation. This is the basis of quality control.

All work is process. A process is a combination of methods, materials, manpower, machinery, activities, etc. which, taken together, produce a product or service. All processes contain inherent variability. The approach in quality improvement is progressively to reduce variation. This is the basis of quality control.

![]() Measurement. Having a measure of how the organization is doing provides guidance for improvement. Measures can focus internally or externally, i.e. on employee satisfaction, or meeting external customer needs.

Measurement. Having a measure of how the organization is doing provides guidance for improvement. Measures can focus internally or externally, i.e. on employee satisfaction, or meeting external customer needs.

People

![]() Teamwork. When people are able to perceive commonality in goals, then it becomes easier to communicate over departmental or functional walls. Teams, by working towards a common collaborative goal, help in breaking down barriers and act as agents for change.

Teamwork. When people are able to perceive commonality in goals, then it becomes easier to communicate over departmental or functional walls. Teams, by working towards a common collaborative goal, help in breaking down barriers and act as agents for change.

![]() People make quality. The role of managers within an organization is to ensure that everything necessary is in place to allow people to make quality products. This in turn starts to create the environment where people are willing to take responsibility for the quality of their own work.

People make quality. The role of managers within an organization is to ensure that everything necessary is in place to allow people to make quality products. This in turn starts to create the environment where people are willing to take responsibility for the quality of their own work.

Continuous improvement

![]() The continuous improvement cycle. The continuous cycle of establishing customer requirements, meeting the requirements, measuring success and continuing to improve can be used internally to fuel the engine of external and continuous improvement. By continually checking customers’ requirements, a company can find areas in which improvements can be made.

The continuous improvement cycle. The continuous cycle of establishing customer requirements, meeting the requirements, measuring success and continuing to improve can be used internally to fuel the engine of external and continuous improvement. By continually checking customers’ requirements, a company can find areas in which improvements can be made.

![]() Prevention. Prevention means causing problems not to happen. The continual process of driving possible failure out of the system breeds a culture of continuous improvement over time.

Prevention. Prevention means causing problems not to happen. The continual process of driving possible failure out of the system breeds a culture of continuous improvement over time.

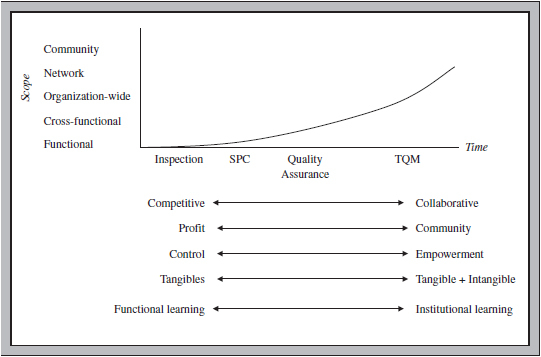

Total quality management is an evolving concept. Over time, the scope of its application has expanded and with this evolution there have been changes in perspective and a growth in the tool-bag of techniques. Garvin20 has suggested that quality has evolved across four distinct historical stages: inspection, statistical quality control, quality assurance and strategic quality management.

Figure 6.2 Evolution of the quality concept.

Stage 1. Inspection stage

In its initial phase of evolution, quality was simply about inspection, sorting and counting. The orientation was one of defect detection.

Stage 2. Statistical process control

In the next phase, statistical quality control tools and techniques were applied to narrow areas of manufacturing and engineering. During this phase, quality was confined to engineering departments. After this point, the range of involvement and application of quality control techniques expanded hugely.

Stage 3. Quality assurance

In the next phase, quality moved from a narrow manufacturing engineering activity to cover the entire production chain, from design to market. It began to involve all functional groups within the company except top management participation. Accompanying the concept's scope expansion, the range of quality techniques also expanded to include quality quality control tools and programme design. The role of all these additions was to ‘assure quality’.

Stage 4. TQM

In the TQM era, the quality notion was expanded to encompass an even broader remit. In this period, quality was adapted as a management tool, and the entire system of an organization as well as the external environment became part of quality. Quality management became ‘the tool’ for all people involved in a company. Vertically, it involved all people from top to bottom and from bottom to top, and horizontally it involved all related departments as well as external organizations. Policy deployment, quality function deployment, performance measurements, the seven management and planning tools, people management and benchmarking were added as quality techniques. In this phase, quality was linked to strategy. For the first time, quality was appreciated to be part of everyone's job and everyone's responsibility.

Each of these stages of evolution represents an expansion of the scope of quality. Hand in hand with the broadening of scope was deepening of application. As the discipline of quality matured, so more techniques were developed or adopted. Additional techniques were adopted to tackle the relevant problems being faced, over time, by the organization. In line with the diversity and greater difficulty of problems faced, richer and more sophisticated techniques were adopted. These changes can be captured as paradigmatic shifts. Dahlgaard Su Mi Park21 captured these shifts as being:

![]() Shifts in the meaning of quality as concept and philosophy. In its early stage of development, quality was related to products and the degree of conformity to specified standards was the major concern. Gradually, Juran's term ‘fitness for use’ became more important, and later on quality began to encompass ‘meeting requirements’ of customers. Subsequently, meeting requirements changed to satisfying the customers and finally this itself changed to delight the customers. With the changing meaning of quality, there was an accompanying shift from perceiving products as tangibles to include both tangible and intangible aspects and thereby capturing almost everything supplied to the customer.

Shifts in the meaning of quality as concept and philosophy. In its early stage of development, quality was related to products and the degree of conformity to specified standards was the major concern. Gradually, Juran's term ‘fitness for use’ became more important, and later on quality began to encompass ‘meeting requirements’ of customers. Subsequently, meeting requirements changed to satisfying the customers and finally this itself changed to delight the customers. With the changing meaning of quality, there was an accompanying shift from perceiving products as tangibles to include both tangible and intangible aspects and thereby capturing almost everything supplied to the customer.

![]() Shift in the understanding of the concept of quality ‘control’. In the first stages of the quality evolution, the meaning of control was understood as inspection, detection or test of the final products. In later stages, control came to represent ‘maintenance’ and latterly it has also started to include improvement. The meaning of the con-

cept of control moved from checking products to building in quality. With these developments the concept changed from backwardlooking activities to forward-looking activities, from passive and reactive to proactive, and from focusing on the results only to focusing on the processes and the interrelationships. Of significant note was the shift from ‘control’ to ‘management’.

Shift in the understanding of the concept of quality ‘control’. In the first stages of the quality evolution, the meaning of control was understood as inspection, detection or test of the final products. In later stages, control came to represent ‘maintenance’ and latterly it has also started to include improvement. The meaning of the con-

cept of control moved from checking products to building in quality. With these developments the concept changed from backwardlooking activities to forward-looking activities, from passive and reactive to proactive, and from focusing on the results only to focusing on the processes and the interrelationships. Of significant note was the shift from ‘control’ to ‘management’.

![]() Shift in the concept of managing people. The basic principle for people management has been changed from ‘control’ aspects to a building aspect. The scientific management model of people management, where people were controlled and ordered, has changed to empowerment. This corresponds to the movement from a backward-looking attitude to a forward-looking attitude, and from a preventing attitude to a creating attitude.

Shift in the concept of managing people. The basic principle for people management has been changed from ‘control’ aspects to a building aspect. The scientific management model of people management, where people were controlled and ordered, has changed to empowerment. This corresponds to the movement from a backward-looking attitude to a forward-looking attitude, and from a preventing attitude to a creating attitude.

![]() Shift in the understanding of the boundary and role of the organization. In the early phases of the quality evolution, an organization was mainly regarded as an economic entity or a profit-making ‘machine’. Gradually this changed to embrace a social function of an organization, as more and more research highlighted the importance of human aspects. In the modern TQM era, the role of an organization has become even more encompassing. Today, an organization is not just regarded as a profit-making social entity, but as an integral part of society. Under this perspective, a company must be operated as a small community within society, and it is responsible not just for its own members, but also for wider societal concerns.

Shift in the understanding of the boundary and role of the organization. In the early phases of the quality evolution, an organization was mainly regarded as an economic entity or a profit-making ‘machine’. Gradually this changed to embrace a social function of an organization, as more and more research highlighted the importance of human aspects. In the modern TQM era, the role of an organization has become even more encompassing. Today, an organization is not just regarded as a profit-making social entity, but as an integral part of society. Under this perspective, a company must be operated as a small community within society, and it is responsible not just for its own members, but also for wider societal concerns.

![]() Shift in the understanding of motivation. The evolution phases of the human motivation factors are closely allied to the evolution of the concept of an organization. In the early phases of organizational development, there was a tendency to see the organization as an economic entity, and the focus was mainly on the tangible aspects of human motivation. It was believed that people were motivated and satisfied by material rewards. However, over time, social aspects have come to be emphasized as important drivers of motivation, together with material rewards. In the TQM era, where organizations have come to be regarded as a community, the motivation aspects have embraced deeper intangible motivation factors, such as self-actualization, self-development, recognition, learning and creativity. The change from a focus on tangible aspects to intangible aspects corresponds to the movement from focusing on extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivational factors.

Shift in the understanding of motivation. The evolution phases of the human motivation factors are closely allied to the evolution of the concept of an organization. In the early phases of organizational development, there was a tendency to see the organization as an economic entity, and the focus was mainly on the tangible aspects of human motivation. It was believed that people were motivated and satisfied by material rewards. However, over time, social aspects have come to be emphasized as important drivers of motivation, together with material rewards. In the TQM era, where organizations have come to be regarded as a community, the motivation aspects have embraced deeper intangible motivation factors, such as self-actualization, self-development, recognition, learning and creativity. The change from a focus on tangible aspects to intangible aspects corresponds to the movement from focusing on extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivational factors.

![]() Shift in the appreciation of feedback and measurement. A similar phenomenon is observed in measurement areas. In the initial stages, quality was measured in defect rates, complaint rates, returns, etc. In the TQM era, two new important measurements

have been introduced. These two measurements are customer satisfaction measurements and employee satisfaction measurements.

Shift in the appreciation of feedback and measurement. A similar phenomenon is observed in measurement areas. In the initial stages, quality was measured in defect rates, complaint rates, returns, etc. In the TQM era, two new important measurements

have been introduced. These two measurements are customer satisfaction measurements and employee satisfaction measurements.

![]() Shift in the understanding of continuous improvement and learning. In the first wave of quality, the primary focus was on improving tangible work processes and changes made by front-line workers. In this stage, the initial tools were derived from statistics and other related methods for diagramming, analysing and redesigning work processes to reduce variability and to enable systematic improvements. In the second wave of quality, the focus shifted from improving work processes to improving how we work. The second wave was initiated in Japan; as early as the 1960s, leading Japanese companies began to mass deploy quality tools. Furthermore, with quality control circle activities everybody participated in quality improvements. In the third wave of quality, the learning aspects become institutionalized as an inescapable way of life for managers as well as for workers. Peter Senge22, analysing the quality movement from the learning aspects, claims that the second wave is well under way in Japan, driven by their seven new tools for management. In his opinion, with a few exceptions, the US is still in the first wave, because the basic behaviour of US managers, especially senior managers, has not really changed much.

Shift in the understanding of continuous improvement and learning. In the first wave of quality, the primary focus was on improving tangible work processes and changes made by front-line workers. In this stage, the initial tools were derived from statistics and other related methods for diagramming, analysing and redesigning work processes to reduce variability and to enable systematic improvements. In the second wave of quality, the focus shifted from improving work processes to improving how we work. The second wave was initiated in Japan; as early as the 1960s, leading Japanese companies began to mass deploy quality tools. Furthermore, with quality control circle activities everybody participated in quality improvements. In the third wave of quality, the learning aspects become institutionalized as an inescapable way of life for managers as well as for workers. Peter Senge22, analysing the quality movement from the learning aspects, claims that the second wave is well under way in Japan, driven by their seven new tools for management. In his opinion, with a few exceptions, the US is still in the first wave, because the basic behaviour of US managers, especially senior managers, has not really changed much.

The history of quality movement shows that it has been able to adapt to new circumstances continuously, and in this way it was able to integrate new ideas, tools and methods. At the same time, the history of the quality movement shows that it has also been able to reach a deeper level in each relevant area regarding its conceptual development and implementation aspects. A point of note with this evolutionary trajectory is that it can be divided into two different dimensions: the quality evolution history of implementation and the quality evolution history of TQM's conceptual development. As quality has matured conceptually, the major weakness explaining many of the failures that we are still witnessing can be said to originate mainly from weaknesses in its implementation.

The factor for TQM success: implementation

Like any programme or effort, TQM's success is affected by how well it is implemented. Gurnani23 suggests that eight essential ingredients can be discerned in TQM implementation:

1 Quality policy. It is almost a statement of human nature that people follow policy, good or bad. A clear and concise policy on quality needs to be stated to ensure that all employees understand what behaviour is expected of them from top management. For instance, in times of conflict in objectives (quantity versus quality of output), managers should not violate their commitment to quality and succumb to the temptation of delivering low quality products simply to achieve a one-off on-time delivery.

2 Senior management commitment. Strong commitment from the management is an essential ingredient. Support must be made transparent to the whole company through adequate resources, monitoring, coherence and absolute top priority to quality improvement programmes. Top management must create a ‘climate’ for quality improvement by their personal attitude if they are to encourage employees to respond favourably towards quality improvement efforts.

3 Steering committee. Steering committee members act out dual roles of ‘quality leaders’ and ‘quality guardians’. It takes deep appreciation and conviction to make the quality improvement effort sustainable over time. This means that steering committee members themselves must first become educated about the quality philosophy: its history, concepts and tools. They need not be involved in the minutiae of the effort, but it is essential that they lead and champion the effort. During the implementation stage of the TQM programmes, the role of the steering committee is to detect any deviation from the planned trajectories and to redirect everything back on track.

4 Employee commitment and involvement. Quality improvement is impossible unless it enlists the commitment of all employees at all levels in the organizational hierarchy. The ingredients for this to happen include frequent participation, enthusiasm and total involvement. Employee involvement is a process of empowering members of the organization to make decisions and to solve problems appropriate to their levels in the organization.

5 Training and problem-solving tools. Training provides a common language and a common set of tools to be used in the firm. Like quality improvement, training education about quality improvement is an ongoing process. Management must consider who must learn what, how and by when.

6 Communication. Effective and efficient two-way communication channels are a prerequisite of any quality improvement programme. Communications signal change from the top management, as well as transmit important messages up and down the vertical and horizontal implementation chain.

7 Standards and measurement. It is essential to have criteria for measuring progress towards the overall aims of the company. Standards serve to stipulate expected performance levels. To reap full benefits, standards must be complemented by other activities such as benchmarking, which help set the improvement direction and targets.

8 Reward and recognition. Recognizing people means informing individuals that their efforts are being appreciated. Teams and individuals who successfully apply the quality process must be recognized and possibly rewarded so that the rest of the organization begins to understand what is expected of them. Without clear feedback, employees tend not to adjust their performance and even become de-motivated because ‘no one seems to notice their efforts’.

To have a successful TQM effort, it is important to have solid managerial techniques in place before the programme is initiated. Employee involvement is a necessity for quality. Managers must be able to identify weak performing areas for improvement and recognize the areas that a company is performing well, so their strength can be enhanced. The summary ingredient in a successful TQM programme is the effective rewarding of employees for quality initiatives and hard work.

Successful implementations of TQM have resulted in dramatic improvements in profits and other tangible measurements. A study conducted by Tatikonda and Tatikonda24, looking at winners of the Malcolm Baldridge Quality Award, revealed that on average these companies achieved a 70 per cent increase in return on sales and a 50 per cent increase in return on assets.

Problems causing TQM failures

While there have been many corporate success stories of quality management, equally there has been an abundance of failures. A survey conducted by Arthur D. Little of 500 manufacturing and service companies found that approximately one-third felt the TQM programme had a 'significant impact’ on their competitiveness. Surprisingly, the remaining two-thirds felt that the TQM programmes did not impact their organization positively. Also, a study conducted by A. T. Kearney of 100 British organizations revealed that only one-fifth felt positive results occurred as a result of the TQM programme25.

A variety of factors impedes effective implementation of TQM programmes. These are:

![]() TQM has been implemented reactively, as a quick fix, blindly following a fad, or simply to boost some individual's ego. Accordingly, it is nothing more than a ‘technique’ that managers feel they must use because it has been adopted in one form or another in a significant number of other organizations.

TQM has been implemented reactively, as a quick fix, blindly following a fad, or simply to boost some individual's ego. Accordingly, it is nothing more than a ‘technique’ that managers feel they must use because it has been adopted in one form or another in a significant number of other organizations.

![]() TQM creates and develops a cumbersome bureaucracy. Many programmes require a significant increase in paperwork and other bureaucratic requirements that supposedly are necessary to track the programme's benefits. Many organizations appear to have created a plethora of mechanisms that demoralize employees who are trying to implement the TQM programme.

TQM creates and develops a cumbersome bureaucracy. Many programmes require a significant increase in paperwork and other bureaucratic requirements that supposedly are necessary to track the programme's benefits. Many organizations appear to have created a plethora of mechanisms that demoralize employees who are trying to implement the TQM programme.

![]() About two-thirds of companies fail in implementing TQM programmes because they create dual structures. Total quality management companies often build new structures of committees and teams in addition to the real organization structure. However, to work the TQM programme must be integrated into the way the business is run on a day-to-day basis.

About two-thirds of companies fail in implementing TQM programmes because they create dual structures. Total quality management companies often build new structures of committees and teams in addition to the real organization structure. However, to work the TQM programme must be integrated into the way the business is run on a day-to-day basis.

![]() TQM is implemented using an off-the-shelf approach. Pre-packaged programmes fail to consider the unique aspects of the company trying to implement the programme.

TQM is implemented using an off-the-shelf approach. Pre-packaged programmes fail to consider the unique aspects of the company trying to implement the programme.

![]() Many TQM efforts have tended to ignore the importance and role of measurement in the quality process. They simply jump on the ‘doing’ because it is much sexier rather than reflect adequately on the feedback and measurement process. Measurement and feed-back are long-term drivers of improvement and have very important bearing in directing behaviour. It is questionable whether adequate measurement processes, techniques and metrics have even been devised. What you measure and how you measure things reflects what you get.

Many TQM efforts have tended to ignore the importance and role of measurement in the quality process. They simply jump on the ‘doing’ because it is much sexier rather than reflect adequately on the feedback and measurement process. Measurement and feed-back are long-term drivers of improvement and have very important bearing in directing behaviour. It is questionable whether adequate measurement processes, techniques and metrics have even been devised. What you measure and how you measure things reflects what you get.

![]() Lack of proper training is another major pitfall of TQM programmes. A lot of the training has tended to be vague, diffuse and not specifically directed to create specific competences for TQM. Additionally, there is an emphasis towards mass training of shop floor employees without the training and involvement of all levels of management. Without a deep appreciation by middle and senior management of all aspects of quality, TQM programmes soon falter and grind to a halt.

Lack of proper training is another major pitfall of TQM programmes. A lot of the training has tended to be vague, diffuse and not specifically directed to create specific competences for TQM. Additionally, there is an emphasis towards mass training of shop floor employees without the training and involvement of all levels of management. Without a deep appreciation by middle and senior management of all aspects of quality, TQM programmes soon falter and grind to a halt.

The above examples represent a few of the possible reasons for failure of TQM programmes.

Examples of TQM failures

Despite its successes, many companies have experienced that simply having a quality programme does not guarantee business success. Several high profile TQM companies have fallen victim to this condition. Among them have been recipients of prestigious quality awards, such as the Baldridge, Deming Prize and EFQM award. These failures include Douglas Aircraft (a subsidiary of McDonnell Douglas Corporation), Florida Power and Light, Wallace Co., Bell Helicopter Textron, Modicon, and British Telecom.

![]() Douglas Aircraft. The company started its TQM programme by training 8000 employees using a 2-week programme and spent additional time preparing the workplace for the implementation of a TQM programme. Two years later, the company found it was no better off than before the programme.

Douglas Aircraft. The company started its TQM programme by training 8000 employees using a 2-week programme and spent additional time preparing the workplace for the implementation of a TQM programme. Two years later, the company found it was no better off than before the programme.

![]() Florida Power and Light halted its TQ programme due to extensive complaints about excessive paperwork from employees. This decision was made in spite of the fact that Florida Power and Light had won Japan's Deming Prize for quality management in 1989. The decision was made when the company's chairman found that many employees believed the quality improvement process had become a tyrannical bureaucracy. Employees believed that the mechanics of the programme were overemphasized. While there were some improvements in the quality of services, the improvements were insignificant compared with the scale of the TQM programme.

Florida Power and Light halted its TQ programme due to extensive complaints about excessive paperwork from employees. This decision was made in spite of the fact that Florida Power and Light had won Japan's Deming Prize for quality management in 1989. The decision was made when the company's chairman found that many employees believed the quality improvement process had become a tyrannical bureaucracy. Employees believed that the mechanics of the programme were overemphasized. While there were some improvements in the quality of services, the improvements were insignificant compared with the scale of the TQM programme.

![]() Wallace Co., an oil field supply company, filed for bankruptcy protection shortly after it had won the Malcolm Baldridge National Quality Award. According to CEO John W. Wallace26, many of the personnel within the organization were too busy making quality presentations after winning the 1990 award, and were not able to devote the necessary time to generate new sales.

Wallace Co., an oil field supply company, filed for bankruptcy protection shortly after it had won the Malcolm Baldridge National Quality Award. According to CEO John W. Wallace26, many of the personnel within the organization were too busy making quality presentations after winning the 1990 award, and were not able to devote the necessary time to generate new sales.

![]() Bell Helicopter Textron held a 36 per cent share of the new helicopter sales market worldwide. The company recognized the increasing need for quality and trained over 3000 people in TQM during the next few years. By July 1992, Bell had not realized any benefits from the programme. In fact, the company's share of new helicopter sales declined to 20 per cent.

Bell Helicopter Textron held a 36 per cent share of the new helicopter sales market worldwide. The company recognized the increasing need for quality and trained over 3000 people in TQM during the next few years. By July 1992, Bell had not realized any benefits from the programme. In fact, the company's share of new helicopter sales declined to 20 per cent.

![]() Modicon, a producer of industrial automation systems, began its TQM programme in the late 1980s. Modicon's senior managers expected near instant results. Needless to say, the quick results did not materialize and it was not long before resistance to the total

quality management programme arose from the senior ranks, who measured the firm's quality programme against short-term financial performance.

Modicon, a producer of industrial automation systems, began its TQM programme in the late 1980s. Modicon's senior managers expected near instant results. Needless to say, the quick results did not materialize and it was not long before resistance to the total

quality management programme arose from the senior ranks, who measured the firm's quality programme against short-term financial performance.

![]() British Telecom launched a quality programme in the late 1980s. The company is still attempting to recover from being bogged down in quality processes and bureaucracy. The company failed to focus on customers and began to dismantle most of its quality bureaucracy27.

British Telecom launched a quality programme in the late 1980s. The company is still attempting to recover from being bogged down in quality processes and bureaucracy. The company failed to focus on customers and began to dismantle most of its quality bureaucracy27.

As we noted earlier, there are many roadblocks to successful implementation of a TQM programme. The most common obstacle is lack of management commitment to the TQM concept. Top management often shift responsibility to middle management for finding solutions to central business problems. Gordon et al.28 describe the seven 'sins’ of TQM that cause the erosion of confidence of employees and management alike:

![]() Reorganization with no real reason, causing damage to people, processes and profit.

Reorganization with no real reason, causing damage to people, processes and profit.

![]() Obsessing over winning a quality award is always the wrong goal.

Obsessing over winning a quality award is always the wrong goal.

![]() Collecting data on every piece of the processes is wasteful and expensive.

Collecting data on every piece of the processes is wasteful and expensive.

![]() Customer satisfaction measurement is often overdone.

Customer satisfaction measurement is often overdone.

![]() Wasting time, effort and money when all employees are trained in SPC.

Wasting time, effort and money when all employees are trained in SPC.

![]() Workers solve non-consequential problems, thus productivity suffers because TQM places all employees above management.

Workers solve non-consequential problems, thus productivity suffers because TQM places all employees above management.

![]() When management is removed from the process of TQM, the sole focus shifts to the process.

When management is removed from the process of TQM, the sole focus shifts to the process.

It is clear that while TQM has proven to be of tremendous value for some companies, for others, approximately two-thirds of companies attempting it, TQM efforts have failed to either produce results or have stalled29. Gordon et al.30 report in a survey that 26 per cent of Fortune 500 CEOs were either ‘disappointed’ or ‘very disappointed’ in their returns on investments in TQM. Many of these programmes are currently being cancelled or have been cancelled due to the negative impact on profits. In fact, TQM is one of few managerial initiatives that began to show declines in the late 1990s31.

This raises the question of effective implementation of quality programmes. Internal marketing plays a role in facilitating the implementation of effective quality programmes. This role and importance of IM is elaborated in the discussion that follows.

Total quality management, marketing and internal marketing

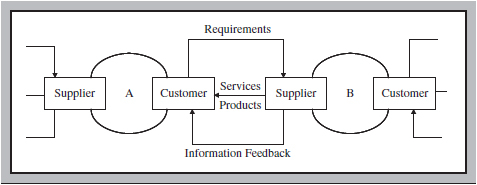

The traditional organizational approach, particularly within marketing, focuses on external customers and markets, with an emphasis upon attracting and retaining customers at a profit. However, marketing has been slow in incorporating a more encompassing interpretation of the ‘customer’, such as that employed in quality management. In quality, there has long been recognition of the importance of both external and internal customers. Indeed, Deming's famous ‘chain reaction’ portrays the organization as a system and receives its impetus from the end-consumer. The system is arranged as a process chain of customer–supplier that encapsulates within itself the external customer. The TQM concept, by adopting a systemic view, is able to shows how an internal focus can lead to positive external outcomes. This works only as long as the internal production system assigns a clear position for the external customer within its chain.

In quality management there is insistence upon the overriding importance of the customer. W. E. Deming conceptualized quality as that which attracts and captures the customer. This view persists in modern conceptualizations of TQM. What is notable in the quality conceptualization is the customer–supplier transposition, whose interlinkages connect to form the production process system. From this, it is clear that any supplier affects all subsequent customers. Initially the impact is upon internal customers, but eventually the effect will extend to external customers. Such thinking is slowly permeating into marketing, especially in the marketing practitioners’ thought-world. As we noted earlier, the internal customer is not a figment of imagination, he or she is real. With the help of TQM thinking, the concept of the internal customer is becoming increasingly accepted and established. This has helped increase the visibility to the practice of internal marketing.

Figure 6.3 The internal customer in the customer–supplier chain.

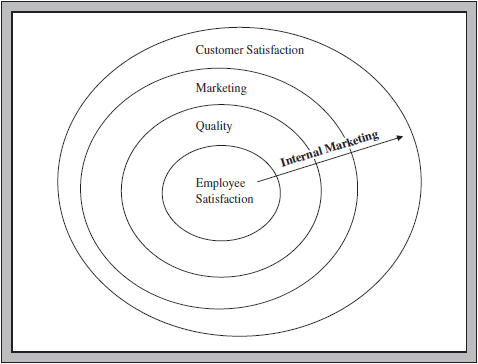

Companies are steadily coming to see the linkages that exist between quality, productivity, employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction. Mitchell32 notes: ‘You can't make happy customers with unhappy employees if the internal customers are satisfied they will love their jobs and feel a sense of pride.’ And as Neave reminds us: ‘ the whole quality of our work is affected by what is supplied to us Awareness of the substantial and involved interleaving customer– supplier structure makes us begin to realize how serious any mistake or any poorly-designed part of the productive system can be ’33

In contrast, unfortunately, many of the conceptualizations of quality by marketers have been generally unhelpful. For example, the distinction of quality by the marketing academics34into two main categories – ‘technical quality’ and ‘functional quality’ – in which technical quality provides the customer with a technical solution and functional quality represents those additional elements that have an impact on customer experiences during the customer–supplier interface process, is generally unhelpful, if not misleading. This is evidenced by the failure of the terms to enter mainstream TQM vocabulary and TQM practice.

Just like external customers, internal customers want to have their needs satisfied. Fulfilling these needs enhances employee motivation and retention. Utilizing the supplier–customer logic, internal marketingthrough its internal focus serves the cause for external customer orientation.

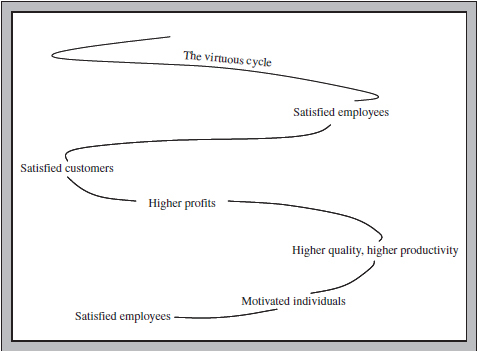

Figure 6.4 The virtuous cycle of internal marketing.

The internal marketing logic is simple: satisfied employees → motivated individuals →higher quality, higher productivity →satisfied customers →higher profits (virtuous cycle).

Internal marketing asks management to view the organization as a market, where there exists an internal supply chain consisting of internal suppliers and customers. The logic of internal marketing is that by satisfying the needs of internal customers, an organization should be in a better position to deliver the quality desired to satisfy external customers. The activation of the interaction processes between internal supplier and customer with each iteration moves the product/service along the supply chain and closer to the end-customer. The higher the degree of employee satisfaction, the higher the possibility of generating external satisfaction and loyalty. Satisfying and delighting customers triggers several bottom line and associated benefits.

Internal marketing as integrator: role of internal marketing in TQM and marketing

A persistent remnant of traditional organizational structuring is that companies continue to live in functional silos. Activities such as quality and marketing are so fundamental that they cannot be considered as separate functions. They are in fact the whole business seen from the point of view of its outcome, that is, from the customer's point of view. In this sense, marketing and quality are all pervasive and are part of everyone's job description. More than this, if we can combine marketing with quality then we are able to integrate the customer into the design of the product/service and develop a systematic process for delivering to these needs. This integration occurs through the enactment and interaction of a set of internal relationships. Companies must gain an understanding of how to develop and manage these internal relationships, with individuals and groups of individuals. This extends not just to employees, but also others who fall within the boundary of internal markets, such as suppliers and distributors. It is the management of these organizational sets of relationships that allows the ‘delivery’ to what marketing has promised externally.

A key question is how the company can develop an effective process for structuring and managing internal relationships. Our answer is that they have to install internal marketing activities. Internal marketing enables this because it is the interface between the internal process of quality and the external customer. By focusing on the management of internal processes and structuring and aligning relationships, internal marketing acts as the driving force in achieving the primary objectives of quality, efficiency, effectiveness, loyalty and profitability.

Total quality management and marketing derive from a common business philosophy that focuses on customer satisfaction for long-term profitability. Internal marketing helps bring the two together by systematically integrating activities. Internal marketing by facilitating employee motivation toward quality consciousness, and hence customer consciousness, can have a major impact upon an organization. By aligning and improving internal relationships and satisfaction, the company can reduce costs, increase profits and build a platform for competitive success.

In a well-managed company, all functions will have a clear understanding of what defines their contribution to the overall mission and objectives. In such companies, customers’ needs and wishes are not seen as the responsibility solely of the organization's marketing function or efforts. Marketing is essential, but it is not the only custodian of the customer. Marketing must co-operate with other people in the organization who perform non-marketing tasks. The case is the same for the quality function. In a large organization, for example, manufacturing, engineering, purchasing, accounting and finance are all jigsaw parts of the internal structure. For the corporate entity, no single management function is effective if it operates in isolation. Multiple operations and people with different skill-sets have to be actively involved in creating and delivering products and services. These cross-functional activities and the people who perform them all have a major influence upon the final outcome. The implication of this is that today's managers must ensure that every employee in all parts of the organization places top priority on the delivery of quality throughout the whole of the customer–supplier chain.

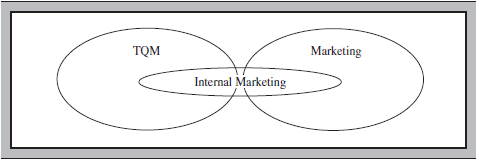

Whilst TQM's focus is on quality of product and service and marketing's focus is on the marketplace, IM is based on a more inclusive and broader perspective because it considers the ‘totality’ of internal and external functions and relationships necessary to get things done. When companies look at their business through their customers’ eyes and measure their performance against their customers’ expectations, then it is not possible to view quality narrowly, as something that the manufacturing department achieves by inspecting products for compliance with specifications and eliminating defective ones. Internal marketing helps TQM in its search for quality improvement by motivating employees toward continuous improvement. Marketing when combined with TQM also means that everyone in all parts of the organization places top priority on customer-led continuous quality improvement. This requires managing all internal and external relationships and processes. Internal marketing structures and enables the effective management of such relationships by facilitating an effective delivery process. Internal marketing is the interface between TQM and marketing (i.e. TQM is the internaldelivery agency, whereas marketing is the external delivery agency, and IM is the facilitating interface agency).

Figure 6.5 Internal marketing as interface agency.

Internal marketing generates involvement and commitment to quality. Involvement concerns not only people, but also includes all organizational resources, such as systems, equipment and information. One primary aim of internal marketing is to assess and help put in place processes to improve effort toward quality and meet the customers’ requirements and needs. To satisfy the needs of the external customers, the company has first to satisfy its internal customers. When this philosophy is applied, the barriers between departments and functions are broken down and removed. Internal marketing includes all individual and organizational functions, activities, communications and elements that a firm uses to create, develop and maintain appropriate interlinkages that result in the delivery of high quality to the final customer. Internal marketing, by helping to focus on integrating marketing with quality, leads to cost savings (i.e. machinery, inspection, testing, rework and complaints costs), which in turn leads to higher productivity through employee motivation.

Internal marketing's role is to help create, interpret, maintain and enhance positive, sustainable and close relationships within the company, thereby facilitating implementation of strategies that engender high levels of satisfaction in the external marketplace. Internal marketing focuses on and is concerned with all integrated activities within the organization (internal relationships). Whilst the focus is to manage the internal marketplace relationships, these internal marketplace relationships influence and enhance external marketplace relationships. Internal marketing complements quality management and external marketing. It melds the internal quality process to external market needs. It is through these actions, not plans and thoughts, that real sustainable competitive advantage is built. In this sense, internal marketing is emerging as a way of raising quality levels in organizations and stimulating corporate effectiveness.

Combining TQM with marketing through internal marketing can lead to optimal co-ordination and integration of operations, activities and efforts for aligned strategy implementation. Combined, the three lead to an integration between quality, employee loyalty, productivity and profits. Internal marketing's co-ordination or integration of operations, activities and efforts is merely an operational means to an end: customer orientation. Internal marketing helps focus the organization toward a customer orientation, which works internally by facilitating the process and behaviours to deliver a quality orientation. Internal marketing, TQM and marketing, when used together, result in greater customer satisfaction and allow the company to sustain a competitive edge.

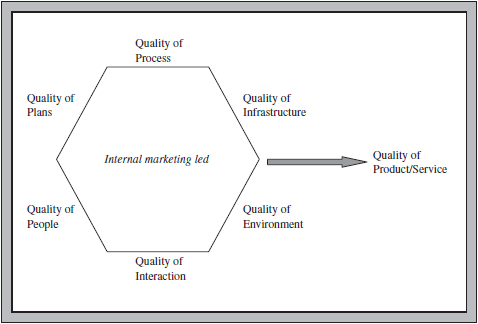

Thus, the success of a quality programme is mediated by the partnership between the employee and the company. Internal marketing works on getting quality by paying attention to:

![]() Quality of processes. Internal marketing plays a role in examining the activities of work and ensuring that the processes are effective in delivering maximum value for customer needs. Internal marketing does this by examining the process for overall aims, assessing and aligning these to strategic goals and then communicating the existence of the process, and informing how the process functions. By raising the awareness of aims and function, internal marketing improves the operational quality of the process.

Quality of processes. Internal marketing plays a role in examining the activities of work and ensuring that the processes are effective in delivering maximum value for customer needs. Internal marketing does this by examining the process for overall aims, assessing and aligning these to strategic goals and then communicating the existence of the process, and informing how the process functions. By raising the awareness of aims and function, internal marketing improves the operational quality of the process.

![]() Quality of infrastructure. Internal marketing assesses the quality of the internal structures and internal resources and activities. It examines how well these processes and activities are managed and co-ordinated.

Quality of infrastructure. Internal marketing assesses the quality of the internal structures and internal resources and activities. It examines how well these processes and activities are managed and co-ordinated.

![]() Quality of interaction. Internal marketing assesses and improves the quality of information exchange, financial exchange and social exchange. As a direct consequence of high ‘quality’ exchange, internal relationships can be improved and more effectively aligned to desired aims.

Quality of interaction. Internal marketing assesses and improves the quality of information exchange, financial exchange and social exchange. As a direct consequence of high ‘quality’ exchange, internal relationships can be improved and more effectively aligned to desired aims.

![]() Quality of environment. Internal marketing assesses the relationship and interaction process between the parties, and the impact of the environment within which the interactions occurs. The quality of the environment determines how well people co-operate and operate. The organizational atmosphere can be described as an artefact of organizational culture, and depicts its reality along dimensions such as level of dependence versus interdependence, conflict as opposed to co-operation, expectations and reciprocity, communication, trust and commitment. A high ‘quality’ environment involves high trust, commitment and reciprocity between involved business parties.

Quality of environment. Internal marketing assesses the relationship and interaction process between the parties, and the impact of the environment within which the interactions occurs. The quality of the environment determines how well people co-operate and operate. The organizational atmosphere can be described as an artefact of organizational culture, and depicts its reality along dimensions such as level of dependence versus interdependence, conflict as opposed to co-operation, expectations and reciprocity, communication, trust and commitment. A high ‘quality’ environment involves high trust, commitment and reciprocity between involved business parties.

![]() Quality of people. Internal marketing assesses current capabilities and competencies of people, and identifies the gaps that need to be filled to make strategies happen. Internal marketing assesses the

competence, experience, know-how, internal relationships, motivation and attitudes necessary for embedding the quality philosophy throughout the organization. It examines for these and formulates plans to generate appropriate reflexes.

Quality of people. Internal marketing assesses current capabilities and competencies of people, and identifies the gaps that need to be filled to make strategies happen. Internal marketing assesses the

competence, experience, know-how, internal relationships, motivation and attitudes necessary for embedding the quality philosophy throughout the organization. It examines for these and formulates plans to generate appropriate reflexes.

![]() Quality of plans. Internal marketing examines and helps the translation of strategies into tactical plans for operations. In the translation process, internal marketing considers what benefits individuals can derive from implementing these strategies, in the long as well as the short term, and then develops appropriate internal marketing strategies to engender buy-in.

Quality of plans. Internal marketing examines and helps the translation of strategies into tactical plans for operations. In the translation process, internal marketing considers what benefits individuals can derive from implementing these strategies, in the long as well as the short term, and then develops appropriate internal marketing strategies to engender buy-in.

Effective co-ordination and integration of these results in:

![]() Quality of product/service. This is what the customers receive. From product/service quality comes customer satisfaction, which is the primary reason for initiating the TQM programme or any other effort.

Quality of product/service. This is what the customers receive. From product/service quality comes customer satisfaction, which is the primary reason for initiating the TQM programme or any other effort.

The internal marketing philosophy builds an interrelationship between quality and external marketing. This it does by structuring appropriate exchanges and building employee relationships. Using internal marketing, companies can effectively interweave the customer's perspective into the quality process. Internal marketing helps build cross-functionalism, where different functions inside and outside an organization work together in teams.

Internal marketing understands that there are links and interdependencies between product/service quality, customer satisfaction, employee relationship and profitability. From this appreciation, internal marketing aids the process of helping everyone in the organization see the linkage between what they do and its impact on the eventual customer relationship. Co-ordinating the internal and external activities in a harmonious manner is essential to establish and quantify the requirements of internal customers (employees), and aids the delivery of external customer satisfaction. This is the key role of internal marketing.

In short, IM focuses on:

![]() integrating and co-ordinating activities within the organization (integrative focus) by

integrating and co-ordinating activities within the organization (integrative focus) by

![]() facilitating interlinkage between external customers (market-led focus) with

facilitating interlinkage between external customers (market-led focus) with

![]() internal quality and continuous improvement of the products/services and processes (efficiency and effectiveness focus),

internal quality and continuous improvement of the products/services and processes (efficiency and effectiveness focus),

![]() through a focus on employees in the organization, who are responsible for the execution of strategies of continuous improvement (internal focus via internal relationships).

through a focus on employees in the organization, who are responsible for the execution of strategies of continuous improvement (internal focus via internal relationships).

Figure 6.6 The internal marketing-led quality diamond.

Internal marketing as strategy and internal marketing as philosophy

Internal marketing is a co-ordinating philosophy because it considers and co-ordinates ‘all’ activities – including internal and external relationships, network interactions and collaborations – by examining all activities involved in satisfying customers throughout the quality supply chain. It is a philosophy because it focuses attention on customer satisfaction and organizational productivity through continuous attention and improvement of the ‘jobs’ that employees execute and the environment in which they execute them. Internal marketing communicates the idea that a major goal of management is to plan and build appropriate close and flexible relationships with internal parties to continuously improve quality.

Internal marketing is a strategy because it triggers appropriate actions to occur, such that strategic words become translated into actions that deliver quality-led customer satisfaction. Internal marketing therefore helps guide the overall thinking in the organization and plays a role in decision making, as well as in the execution of predetermined plans.

The main role behind internal marketing within a TQ setting is to structure and enhance appropriate internal relationships with employees and collaborators. By bringing together quality and marketing, internal marketing's main goal is to produce and deliver customer satisfaction. This allows the company to realize strategies for sustainable competitive advantage.