chapter five

A framework for

empowering employees

Introduction

We saw in Chapter 2 that empowerment is an essential component of internal marketing, particularly in the area of services marketing. Whilst a great deal has been written on the subject of empowerment (also referred to as job involvement, and as employee participation) in the manufacturing industries, its application in the services area is surprisingly, as yet, still relatively underdeveloped. However, any rigorous examination of the literature shows that empowerment is not suitable for all occasions or all types of employees, as it can have both positive and negative consequences for employees and the organization. This chapter outlines a contingency framework for the empowerment of contact service employees. It is argued that the appropriate levels and the types of empowerment given to employees depend upon a combination of the complexity (or variability) of customer needs and the degree of task complexity (or variability) involved in delivering the services. It is also argued that, in any empowerment framework, it is essential that the degree and the type of empowerment be explicitly incorporated.

Background

The special nature of services, and in particular the simultaneity of production and consumption, is one of the major reasons that many services marketers argue that contact employees should be allowed a degree of discretion when dealing with customers. For instance, Grönroos argues that the interactive nature of services provides empowered employees an opportunity to rectify mistakes and an opportunity to increase sales:

‘Ideally, the front-line employee...should have the authority to make prompt decisions. Otherwise, sales opportunities and opportunities to correct quality mistakes and avoid quality problems in these moments of truth are not used intelligently, and become truly wasted moments of opportunity to correct mistakes, recover critical situations and achieve re-sales and cross-sales.’1

However, other authors argue that service employees should have little or no discretion. For instance, Smith and Houston2 propose a 'script-based’ approach to managing customer and employee behaviour to control behaviour and process compliance. That is, Smith and Houston envisage little or no room for participation by employees. Levitt3 forcefully argues for a ‘production line’ approach and the ‘industrialization’ of services in order to improve the productivity of services. One of the key elements in this approach to services is that it leaves little room for discretion for service employees.

Mills4 argues that the degree of management control over service employees (or conversely the degree of employee empowerment) should depend on the structure of the service system: for low contact standardized services behaviour can be controlled by mechanistic means such as rules and regulations. For high contact, highly divergent services (that is, those requiring a high degree of customization), Mills suggests that employee self-management and peer-reference techniques are more successful. Even Grönroos recognizes that not all decision making can or should be decentralized as ‘chaos may follow in an organization if strategic decisions, for example, concerning overall strategies, business missions and service concepts, are not made centrally’5.

The foregoing suggests that the approach to participation is a contingent one. Before outlining the proposed framework, we begin with a discussion of the nature of empowerment, the rationale for it, and the differences in degree and types of empowerment that can be given to employees.

The nature of empowerment

Empowerment has been defined in numerous ways, but most authors agree that the core element of empowerment involves giving employees discretion (or latitude) over certain task-related activities6. Empowerment implies that front-line employees are allowed to exercise a degree of discretion during the service delivery process. Three types of discretion can be distinguished, namely routine, creative and deviant discretion7. Routine discretion is exercised where employees select an alternative from a list of possible actions in order to do their job (e.g. investment counsellors recommending a product from a list of the organization's products). Creative discretion is exercised where employees themselves have to develop alternative methods of performing a task (e.g. a professor's discretion over the content of a lecture). Creative behaviours are not specified by the organization, but are regarded positively by the organization. Deviant discretion, on the other hand, is negatively regarded by the organization, as it involves behaviours that are not part of the employee's formal job description and outside the area of the employee's authority.

Whilst discretion is regarded as perhaps the most important feature of employee empowerment, there are a number of other features of empowerment that are essential for the effective implementation of service delivery strategies. For instance, in addition to employee discretion, Bowen and Lawler8 also include in their definition of empowerment the sharing of information regarding the organization's performance, rewards based on organizational performance, and knowledge that enables employees to understand and contribute to organizational performance. Berry goes further and argues that:

‘Empowerment is a state of mind. An employee with an empowered state of mind experiences feelings of 1) control over how the job shall be performed, 2) awareness of the context in which the work is performed, 3) accountability for personal work output, 4) shared responsibility for unit and organizational performance, and 5) equity in the rewards based on individual and collective performance.’9

The important point to note is that both these sets of authors regard as important the sharing of information so that the employees understand the context in which they work. They also regard as important that empowered employees are remunerated appropriately and in the case of Berry that these rewards are based on individual and collective performance.

Reasons for empowering employees

It has already been intimated that one of the major reasons for empowering front-line service employees is so that they can take advantage of sales opportunities and cross-selling opportunities resulting from the interactive nature of the service delivery process. More generally, the reasons for empowering employees can be divided into those that improve the motivation and productivity of employees and those that improve service for the customer and market the service products more effectively.

In services marketing empowerment of the front-line can lead to both attitudinal and behavioural changes in employees. Attitudinal changes resulting from empowerment include increased job satisfaction, reduced role stress and less role ambiguity.

Empowerment also has important behavioural consequences. For instance, empowerment can increase the self-efficacy of employees as discretion allows them to decide the best way to perform a given task. Empowerment leads to employees becoming more adaptive. Empowerment also leads to quicker response by employees to the needs of customers, as less time is wasted in referring customer requests to line managers. In situations where customer needs are highly variable, empowerment is crucial in allowing employees to customize service delivery.

From a marketing perspective, because of the simultaneity of the production and consumption of services and the frequent involvement of the customer in the production process, there is far more scope and opportunity for customization of service products than manufactured products. Customization of the service during delivery can also be used as a source of differentiation and competitive advantage, and increase customer satisfaction. This, obviously, suggests the need to empower contact employees appropriately contingent upon the type of service product being provided.

Service recovery is another area where empowerment plays a vital role, as service failures are inevitable. Speedy service recovery is essential when service failures occur. Otherwise, if service failures are not rectified quickly and satisfactorily, customers may lose faith in the overall reliability of the service. Schlesinger and Heskett10, for instance, note that empowerment of front-line employees is one of the key components in breaking the ‘cycle of failure’ in services. It is also a vital component in a service firm's strategy of maintaining customer satisfaction.

Degree and types of empowerment

Bowen and Lawler11 suggest that the degree of empowerment varies from control oriented at one end and involvement orientation at the other. Control orientation is typified by the production line approach, where there is no empowerment of employees. Suggestion involvement is the next level of involvement in Bowen and Lawler's schema, followed by job involvement, and finally leading to high involvement.

Suggestion involvement need not involve any changes to the basic production line management approach, as it basically only allows employees to suggest changes in the service delivery and product changes, which may or may not be adopted. This type of involvement of employees includes activities such as employee attitude surveys, problem solving groups and quality circles (which have been widely used in the manufacturing sector). These techniques are designed basically to elicit information from employees. Other techniques, such as house journals and team briefing, are used to impart information to employees (in order to empower them) so that they are more effective in the performance of their jobs.

Job involvement involves a significant departure, as it gives employees discretion over various aspects of their jobs and how they organize their work. Such discretion can be given either to individuals or to groups of individuals (i.e. workgroups). Discretion given to workgroups may lead to them becoming semi-autonomous workgroups or self-managing teams. Self-managing teams are allowed to organize how they undertake tasks within the group.

Even higher levels of involvement occur where employees are involved not only in the performance of their jobs, but also in the organization's performance. According to Bowen and Lawler, high involvement occurs where:

‘Business performance information is shared. Employees develop skills in teamwork, problem solving, and business operations. They participate in work unit management decisions. There is profit sharing and employee ownership.’12

At the service delivery level, high involvement in the Bowen and Lawler sense is not relevant, as it does not directly empower contact service employees. High involvement in Bowen and Lawler's schema is an indirect method of empowering employees. Hence, in what follows Low Empowerment describes situations where employees are encouraged to make suggestions regarding the way in which services are delivered but management is not bound to act on the suggestions. High Empowerment, on the other hand, is used to describe situations where employees have a high degree of autonomy and discretion over the way in which they undertake service delivery tasks. Obviously, intermediate situations occur where moderate degrees of discretion are allowed to employees and thus are moderately empowered.

In any discussion of empowerment it is also important to distinguish between the types of discretion exercised. In fact, as mentioned above, the degree of empowerment that is appropriate for different types of services provided can be described by the level of creative and routine discretion exercised by employees. Clearly, a high degree of routine discretion is not the same as a high degree of creative discretion.

A framework for empowering service employees

Whilst the contingent nature of empowerment is implied by a number of authors, the only existing contingency framework for empowering service employees is that of Bowen and Lawler. According to Bowen and Lawler, there are five contingencies of empowerment, namely business strategy, tie to the customer, technology, business environment and types of employees. Before proposing an alternative framework, a brief discussion of these contingencies follows below.

![]() Business strategy. Firms undertaking a differentiation business strategy or a strategy that involves high degrees of customization and personalization of services should empower their employees. However, firms pursuing a low cost, high volume strategy should use a production line approach to managing employees.

Business strategy. Firms undertaking a differentiation business strategy or a strategy that involves high degrees of customization and personalization of services should empower their employees. However, firms pursuing a low cost, high volume strategy should use a production line approach to managing employees.

![]() Tie to the customer. Where service delivery involves managing (long-term) relationships with customers rather than just performing a simple transaction, then empowerment is essential. This is particularly important in the case of industrial/organizational customers, where relationships are not only long term but the value of individual transactions is high.

Tie to the customer. Where service delivery involves managing (long-term) relationships with customers rather than just performing a simple transaction, then empowerment is essential. This is particularly important in the case of industrial/organizational customers, where relationships are not only long term but the value of individual transactions is high.

![]() Technology. If the technology involved in service delivery simplifies and routinizes the task of service personnel, then a production line approach is more appropriate than empowerment. However, where the technology is non-routine or complex, then empowerment is more appropriate.

Technology. If the technology involved in service delivery simplifies and routinizes the task of service personnel, then a production line approach is more appropriate than empowerment. However, where the technology is non-routine or complex, then empowerment is more appropriate.

![]() Business environment. This relates to the relative predictability/variability of the business environment and that of customer needs. Bowen and Lawler illustrate this with examples of airlines who serve customers with a ‘wide variety of special requests’, which makes it impossible to anticipate many situations and therefore to ‘program’ employees to handle them. This is contrasted with a fast-food restaurant, where customer requirements are simpler and more predictable, and a production line approach is more appropriate.

Business environment. This relates to the relative predictability/variability of the business environment and that of customer needs. Bowen and Lawler illustrate this with examples of airlines who serve customers with a ‘wide variety of special requests’, which makes it impossible to anticipate many situations and therefore to ‘program’ employees to handle them. This is contrasted with a fast-food restaurant, where customer requirements are simpler and more predictable, and a production line approach is more appropriate.

![]() Types of employees. Bowen and Lawler recognize that empowerment and production line approaches require different types of employees. Employees most likely to respond positively to empowerment are those that have high growth needs and those that need to have their abilities tested at work. Where empowerment requires teamwork, employees need to have strong social and affiliative needs and good interpersonal and group skills. Empowerment requires Theory Y type managers, who allow employees to work independently to the benefit of the organization and its customers. The production line approach requires theory X type managers, who believe in close supervision of employees.

Types of employees. Bowen and Lawler recognize that empowerment and production line approaches require different types of employees. Employees most likely to respond positively to empowerment are those that have high growth needs and those that need to have their abilities tested at work. Where empowerment requires teamwork, employees need to have strong social and affiliative needs and good interpersonal and group skills. Empowerment requires Theory Y type managers, who allow employees to work independently to the benefit of the organization and its customers. The production line approach requires theory X type managers, who believe in close supervision of employees.

Whilst Bowen and Lawler's classification scheme is helpful in describing some of the situations in which service employees should be empowered, it is difficult to see what the underlying dimensions are behind these contingencies. The major weakness of Bowen and Lawler's contingency framework is that it does not distinguish between customerand employee-related contingencies. Bowen and Lawler also seem to suggest that the decision to empower employees is, in part, a consequence of engaging employees with high growth, social and interpersonal needs, rather than vice versa. In fact, the type of employees is not a contingency but controllable factor in the delivery of services.

We propose that the appropriate levels and the types of empowerment given to employees depend upon a combination of the complexity (or variability) of customer needs and the degree of task complexity or variability involved in delivering the customer needs. The major reason for this is the fact that in services the degree and type of interaction between customer and contact employees can have a major impact on the degree of complexity of the task that a contact employee has to perform in order to satisfy customer needs. Complexity of customer needs includes, amongst other things, product complexity, complexity of relationship (tie to the customer) and variability in the needs of customers. Task complexity or variability is partly determined by, amongst other things, the type of technology employed and partly by the service product. Both of these are determined by the basic business strategy that is employed by the organization.

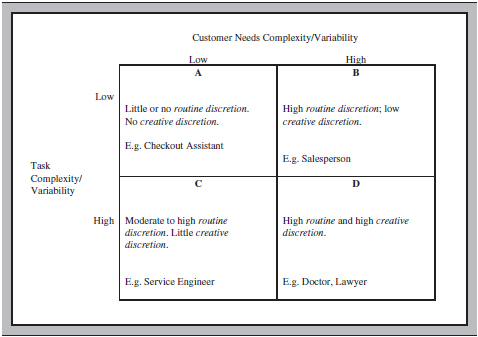

This is shown in the two-by-two matrix in Figure 5.1, together with the type of discretion exercised in each of the different situations. In Figure 5.1, Box A describes a situation where the variability in the needs of the customer is low and the complexity of the task performed is also low. An example of such a situation is the service provided by a checkout assistant in a supermarket. Employees in such situations have little or no routine or creative discretion in the way they perform their tasks or the service that they offer to customers. In some situations, customers may be allowed to customize the product by choosing from a limited amount of options. For instance, Burger King's ‘Have It Your Way’ allows customers to have their burgers with or without cheese. However, whilst option personalization increases the discretion of the customer, it does not affect the discretion that the employee has over the performance of his or her job.

Box B describes a situation where the task is still relatively simple, but the needs of the customer are more complex or variable. The situation is typical of one that is often faced by salespeople. The salesperson is allowed in this situation to offer different options to the customer in order to meet the needs of the customer. However, the options that the salesperson offers to the customer must be those that the salesperson has been authorized to offer and no other. The salesperson is not allowed to (or required to) create new options that may meet the customers needs. However, the options that the salesperson chooses to offer to the customer depend upon an assessment and an understanding of the needs of the customer and therefore requires a certain amount of creativity (or adaptiveness) on the part of the salesperson. Hence, salespeople may be allowed to exercise a small amount of creative discretion. Salespersons are also allowed a certain amount of discretion in how they perform their job. For instance, salespeople may be allowed to schedule their own calls on prospective customers rather than having to follow a prescribed routine. Salespersons also have discretion as to how they make the sales pitch.

Figure 5.1 The relationship between customer needs, task complexity and discretion. Source: based on Willman, P. (1989). Human resource management in the service sector. In Management in Service Industries (P. Jones, ed.), Chapter 14, pp. 209–22. London: Pitman.

Box C describes a situation where customer requirements are relatively simple, but the task is complex. An example of such a situation is where a service engineer is required to repair a photocopier, for instance. The task required to perform the service is complex in that it requires technical expertise. The organization therefore relies on the expert judgement of the employee to perform the task and allows the employee a high degree of discretion in how they perform the required tasks. However, this discretion is usually limited to alternative (usually approved) methods of working to provide the required service. The service engineers do not have any creative discretion. That is, they do not normally provide customized solutions to the customers. In any case, as the customer needs are fairly simple, creative discretion is not required.

Box D describes a situation where the needs of the customers are highly variable and the solutions required to meet the needs of the customer are also highly variable and complex. Such situations inevitably require customized solutions. The relationship between a doctor and a patient is typical of such a situation. Typically, the doctor has a great deal of latitude in the treatment of patients. Even here, there are limits to the degree of discretion, as the degree of latitude is limited to the area of expertise of the doctor or, in more general terms, the expert.

In all the above cases, when employees go beyond the degree of discretion allowed them, they are exercising deviant discretion. Such behaviour can be detrimental to the organization and most organizations would regard such behaviour as a disciplinary matter.

Dimensions of customer needs and task complexity

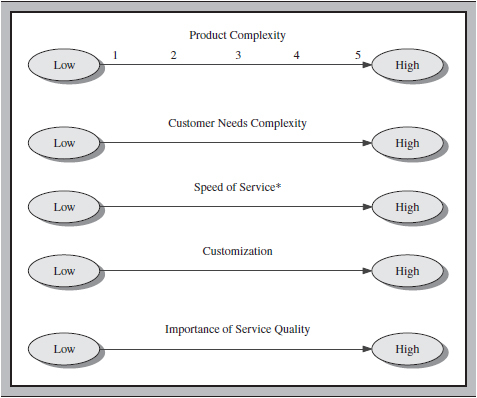

The matrix above provides organizations a fairly high level view of empowerment issues. In order to make decisions regarding the degree of empowerment that is appropriate for the specific context that an organization faces, it is necessary to specify more precisely the dimensions of the contingencies of task complexity and customer needs complexity/variability. For instance, in order to understand the degree of customer needs complexity, the organization needs to examine its service product from a customer perspective and identify the essential features that are important to customers. Review of the literature suggests that the major facets of customer needs complexity for services are service product complexity, customer needs complexity/variability, importance of speed of service, customization and the importance of service quality (see Figure 5.2). The links between these features of service and empowerment are discussed below.

1 Service product complexity. With complex products, customers expect a high level of expertise from contact employees. Hence, the greater the product complexity (from the customer's perspective), the greater the need to empower employees. High levels of empowerment give customers greater confidence in the ability of the contact employee (and the organization) to deliver the service. For instance, management consultancy and education are highly complex products, and customers of these products expect a high level of autonomy on the part of consultants and college professors in the delivery of the service.

2 Customer needs complexity/variability. The more complex or variable the needs of the customer, the greater the need for empowerment. Customers do not wish to be held up whilst the employee consults with a line manager, because the customer's needs vary from the standard service product.

Figure 5.2 Features of customer needs complexity. *Speed of service is a reversed scored item. That is, the faster the speed of service needs to be, the more likely it is that a production line approach will be employed.

3 Importance of speed of service. The speed with which customers expect a service delivery to be completed is an important aspect of any service product. The greater the importance of speed of service, the less appropriate is empowerment of contact employees, as speed is often gained by standardizing service delivery routines.

4 Customization. The degree to which customers expect products to be tailored to their specific needs. The greater the requirement for customization, the greater the need for empowerment.

5 Importance of service quality. Service quality is a complex area of service products. Berry et al.13 have shown that customers assess service quality on five main dimensions, namely reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy and tangibles (in that order of importance). The responsiveness, assurance and empathy variables are obviously heavily dependent upon contact employees. Hence, the higher the level of responsiveness, empathy and assurance (and hence the service quality) expected by the customer, the greater is the need to empower contact employees.

Dimensions of task complexity

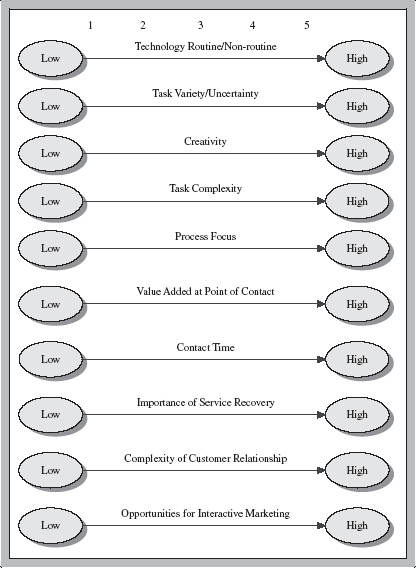

Similarly, organizations need to identify the key determinants of taskrelated activities which determine the features of the service product and the service delivery process (see Figure 5.3). The discussion above and an examination of the literature suggests the following major task-related contingencies for empowerment (see Figure 5.3).

1 Technology (routine versus non-routine). This refers to the degree to which technology routinizes service tasks. The greater the nonroutine nature of tasks, the greater the need for empowerment. The technology dimension also captures the extent to which services are equipment rather than people focused. The greater the people-oriented (and, hence, non-routine) nature of the service, the greater the need for empowerment.

2 Task variety/uncertainty. The extent to which an employee needs to be flexible and to perform non-routine tasks in order to meet non-routine needs of customers. This does not necessarily require the employee to be creative. That is, employees may be able to cope with task variety by being given routine discretion (rather than creative discretion). Generally, the greater the task variety, the greater is the need to empower employees. Otherwise, employees would need to constantly liaise with their line managers before undertaking the required tasks.

3 Creativity. The degree to which an employee is required to be creative (that is, required to generate specific solutions for specific customer needs) or innovative in order to meet customer needs. The greater the requirement for employees to be creative, the greater is the need for empowerment. In this case, it is obvious that employees need to be given creative discretion.

4 Task complexity/difficulty. The degree of complexity of the task depends on the number and sequence of steps required to perform the task or the knowledge intensity. Generally, the greater the complexity of the task, the greater will be the requirement for formal training of employees. The need for empowerment varies directly with task complexity.

5 Process versus product focus. The degree to which the service delivery process is important compared with the product itself. Process orientation requires greater empowerment, whereas product focus requires more of a production line orientation.

Figure 5.3 Features of task complexity.

6 Value added at point of contact. This refers to the proportion of value added by contact employees (front office) compared with back office employees. This is usually reflected in the relative proportion of front and back office employees. The greater the value added by contact employees, the greater is the need for empowerment.

7 Contact time. The duration of time per transaction spent by an employee in delivering a service compared with the total time spent by the customer in receiving the service. The greater the contact time, the greater is the interaction between the customer and the contact employee. As a consequence, high contact services increase the uncertainty in the delivery process and, hence, the need for empowerment varies directly with the contact time between the service provider and the customer.

8 Importance of service recovery. The degree of importance placed on rapid service recovery. The greater the need to recover service quickly, the greater the need to empower employees to take remedial action.

9 Complexity of customer relationship with the organization. This refers to the extent to which transactions are part of an ongoing multi-faceted relationship rather than simple transactions. The longer the relationship and the greater the multi-faceted nature of the relationship, the greater is the complexity of the relationship (compare with Bowen and Lawler's ‘tie to the customer’ contingency). The greater the complexity of the relationship, the greater is the need to empower employees. Key account managers may be appointed where the particular relationships are complex and financially important in order to manage the relationship.

10 Opportunities for interactive marketing. The extent to which opportunities exist for selling additional services to customers to meet their wider needs. The greater the extent of opportunities for interactive marketing, the greater is the need to empower employees to take advantage of the opportunities.

The schema above is partly based on Silvestro et al.'s14 six-point service delivery process classification schema. The variables in Silvsetro et al.'s schema are equipment versus people focus, customer contact time, degree of customization, degree of discretion, value added by front office activities versus value added by back office activities, and product versus process focus.

Silvestro et al.'s equipment versus people focus variable is incorporated under the technology variable in our schema. The discretion (or empowerment) variable is excluded, as it is an outcome in our model and not an input variable as it is in the Silvestro et al. schema. Customization is excluded under the task complexity dimension, since it would involve double counting, as it already appears under the customer needs complexity dimension. It is also excluded because task variety, creativity and complexity are determined to a large extent by the degree of customization that employees are asked to perform. The business strategy variable has also been excluded, as its implementation should be reflected in all the variables that make up task complexity. Its inclusion would, therefore, involve double counting. The other variables in our schema are included as a result of the previous discussion on empowerment.

Developing indices of customer needs and task complexity

In order to make the determination of the level of task complexity and customer needs complexity more systematic, the identified attributes of each of these dimensions can be rated on a scale and all the ratings summed to give an index for the dimension. For instance, the attributes identified for customer needs complexity can be rated in terms of their importance to the customer and the individual ratings summed to give an index of the overall importance of all the identified attributes.

In Figure 5.2, for example, each attribute of customer needs complexity is rated on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = Low, 5 = High) and the score on each attribute is used to form an index of complexity by summing across all the identified attributes. The total score (or index) can then be broken down into intervals which match the degree of empowerment. In the example above, with five identified attributes, the possible scores range from 5 to 25. Scores between 5 and 10 suggest a production line approach. Suggestion involvement is appropriate for scores between 11 and 15, job involvement with moderate degrees of routine and creative discretion for scores between 16 and 20, and job involvement with a high degree of creative discretion for scores between 21 and 25. The assumption above is that all attributes are equally important. If this is not the case, then appropriate weights need to be attached to each variable and the index recalculated. Also, each of the attributes above needs to be rated on the level of routine and creative discretion that is required to implement it. This information can then be used to help with the classification of the index scores.

Similarly, using a five-point scale system similar to that for customer needs complexity above, an index can be calculated for task complexity (see Figure 5.3) by summing across the variables and categorizing the scores into intervals, also similar to the above. The only difference is that, because of the different number of variables, the index ranges from 10 to 50 points rather than 5 to 25 points. As with the customer needs complexity variable above, each of the task complexity attributes needs to be rated on the level of routine and creative discretion that is required to implement it. This information can then be used to help with the classification of the index scores. Scores between 10 and 20 suggest a production line approach. Suggestion involvement is appropriate for scores between 21 and 30, job involvement with moderate degrees of routine and creative discretion for scores between 31 and 40, and job involvement with a high degree of creative discretion for scores between 41 and 50. Once again, the assumption above is that all attributes are equally important. This is unlikely in most cases and therefore appropriate weights will need to be attached to each variable and the index recalculated.

The final requirement is to plot the customer needs complexity scores against the task complexity scores to obtain the right degree of empowerment. The actual level of empowerment chosen will be a compromise between customer needs and task requirements. The scores on routine and creative discretion help to decide the type of empowerment that employees should be given.

The general application of the model outlined above may be illustrated by looking at two examples of highly successful organizations from the airline industry, namely Singapore Airlines and Southwest Airlines. Southwest Airlines specializes in short haul flights (less than 90 minutes) in the USA. It offers the lowest fares in specific markets. The airline provides a ‘no-frills’ service, that is, no meals, no assigned seats or baggage transfer between airlines. Southwest places a great deal of emphasis on cost reduction. For instance, Southwest can turn its aircraft around in 17 minutes compared with an average of 45 minutes for competing carriers. Southwest pays its employees average salaries plus profit sharing15. Budget airlines similar to Southwest Airlines, such as EasyJet and Go, have also emerged in Europe and follow roughly similar strategies and practices as the pioneer Southwest Airlines.

Singapore International Airlines (SIA), on the other hand, specializes in long haul flights, particularly for the business executive market. SIA is one of the most profitable international carriers. It is regularly nominated as best airline, particularly for service. In fact, it aims to be ‘the airline for fine service’. Its philosophy is that the customer comes first and that staff have to be flexible in dealing with customers. Employees are highly trained and paid above-average salaries.

From the limited information above, using the customer needs complexity and task complexity as outlined in Figures 5.2 and 5.3, one would expect the score for Southwest Airlines on the customer needs complexity to be between 5 and 10 (or perhaps slightly higher), and the score on task complexity to be between 10 and 20. That is, in the main, one would expect that Southwest Airlines would employ a production line approach in its people policies and that employees would be given very little discretion in their work.

In contrast, for SIA one would expect the score on the customer needs complexity to be between 31 and 40, and the score on task complexity to be between 41 and 50 (or lower). That is, in the main, one would expect that SIA would employ a human resource management (HRM) policy of job involvement with moderate to high levels of routine and creative discretion given to its employees.

The application of the model at the job level can be illustrated with the example of the different levels of empowerment given to different employees in hospitals when dealing with patients. The level of discretion given to receptionists and orderlies, for instance, is extremely low. This is because the customer needs and job requirements are relatively simple. However, the discretion given to nurses is higher because of the variability in the needs of customers, although the jobs that nurses are required to do are still relatively simple. On the other hand, the job of the radiographer may be complex, but the needs of the patient are relatively simple, that is, to be X-rayed. Hence, radiographers, because of their technical knowledge, are likely to have a high degree of routine discretion but little creative discretion. Doctors and consultants, on the other hand, because of their expertise and the complex nature of their patients’ needs that they must deal with, have high levels of creative discretion.

Zones of empowerment

Within each of the quadrants of empowerment framework (Figure 5.1), there is a specific level of empowerment that is consistent with the specific task being performed. However, the multi-faceted nature of jobs that employees are asked to perform means that, whilst the majority of tasks fall within the parameters of the discretion allowed to them, there may be others where management wishes to limit the discretion allowed to employees.

To further enhance the operationalization of empowerment within organizations, employees need to be guided as to when they can exercise discretion and when they cannot. One simple method of doing this is to group tasks into empowerment zones16. Safe (Green) zones are situations where employees are allowed and expected to make decisions independently. Low-risk (Amber) zones are situations where the employee may consult their manager, and high-risk (Red) zones are situations where consultation with a manager is mandatory.

The zoning is determined by the degree of potential cost or loss the organization may incur as a result of a wrong decision being made by an employee. Hence, in the case of a doctor for instance, in the safe zone (for instance, prescribing medication for a cold), he or she is allowed full discretion. However, where surgery is involved, for instance, the doctor may be required to seek a second (or third) opinion from another colleague, or even to refer the patient to a specialist. In this particular case, there is also a high risk to the patient as well as the organization, hence the curtailment of discretion. In service recovery situations, a limit on the degree of discretion may be linked more directly to costs by placing a financial ceiling on the costs that can be incurred to rectify mistakes. For instance, Federal Express allows its employees to spend up to $100 to rectify customer-related problems17.

Costs of empowerment

Empowerment is not without its costs. One of the consequences of empowerment is that it increases the scope of employees’ jobs. This requires that employees are properly trained to cope with the wider range of tasks required of them. It also impacts on recruitment, as it is necessary to ensure that employees recruited have the requisite attitudinal characteristics and skills to cope with empowerment. Research conducted by Hartline and Ferrell18 shows that empowerment can have both positive and negative outcomes for employees. They found that, although empowered employees gained confidence in their abilities (self-efficacy), they also experienced increased frustration (role conflict). This is because empowerment leads to employees taking on extra responsibilities. Additionally, the increased responsibilities and improved skills required from empowered employees often means that employees must be better compensated, thus adding to the labour costs.

Empowerment can also slow down the service delivery process as the empowered employee attempts to individualize the service for customers, thereby reducing the overall productivity of the service. This can be frustrating for customers waiting to be served. In addition, individualization of a service could potentially be perceived to be unfair in situations where employees are observed not to be adhering strictly to procedures. Another downside occurs in situations where employees are empowered to rectify service failures by give-aways. The obvious danger is that employees give too much away.

Another major dysfunctional aspect of empowerment is that employees may consciously or unconsciously use their discretion disproportionately to bestow a better service on customers who are similar to them. In other words, customers who are similar in terms of age, gender, ethnicity and other personal characteristics receive higher levels of service than those customers who do not share similar characteristics to the employee19.

Summary

This chapter has outlined a framework for the empowerment of contact service employees based on customer needs complexity and task complexity. It has further outlined a methodology for determining the levels and type of empowerment that employees should be given. We believe that the distinction between creative and routine discretion is an important one and have, therefore, incorporated it into the model outlined. The chapter also suggests a system of grouping or zoning tasks, which defines the limits of employee discretion more precisely and guides employees in their day-to-day tasks. It must be emphasized here that the lessons learned with respect to services can be easily transferred to non-service environments.

The framework developed addresses three important elements in empowerment decisions, namely when to empower employees, how much discretion should be given and what type of discretion should be given to them. The indexing and zoning systems provide a practical methodology for operationalizing empowerment within organizations. Used correctly, empowerment can offer considerable competitive advantages to service firms.

The effective implantation of empowerment within an organization requires, in addition to discretion over service tasks, that employees have the requisite information to perform their tasks and understand their role in the service delivery process. Appropriate recruitment procedures and training are also necessary to ensure that the front-line employees have the requisite personal characteristics and skills to cope with empowerment, as not all employees can cope with the extra responsibilities associated with empowerment. It is also essential that empowered employees are remunerated according to the level of responsibility and skills required of them.

References

1. Grönroos, C. (1990). Service management: a management focus for service competition. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 1 (1), 6–14. Quotation from p. 9.

2. Smith, R. A. and Houston, M. J. (1983). Script-based evaluation of satisfaction with services. In Emerging Perspectives on Services Marketing (L.L. Berry et al., eds). Chicago: American Marketing Association, pp. 59–62.

3. Levitt, T. (1972). Production line approach to service. Harvard Business Review, September/October, 41–52. Levitt, T. (1976). The industrialization of service. Harvard Business Review, 54 (September/October), 63–74.

4. Mills, P. K. (1985). The control mechanisms of employees at the encounter of service organizations. In The Service Encounter (Czepiel, J. A. et al., eds). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

5. Grönroos, C. (1990). Op. cit., p.10.

6. Bowen, D. E. and Lawler, E. E. III (1992). The empowerment of service workers: what, why, when, and how. Sloan Management Review, Spring, 31–9. Conger, J. A. and Kanungo, R. N. (1988). The empowerment process: integrating theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 13 (July), 471–82. Schlesinger, L. A. and Heskett, J. L. (1991). Breaking the cycle of failure in services. Sloan Management Review, 17–28.

7. Kelley, S. W. (1993). Discretion and the service employee. Journal of Retailing, 69 (1), Spring, 104–26.

8. Bowen, D. E. and Lawler, E. E. III (1992). Op. cit., p. 32.

9. Berry, L. L. (1995). On Great Service, p. 208. New York: The Free Press.

10. Schlesinger, L. A. and Heskett, J. L. (1991). Breaking the cycle of failure in services. Sloan Management Review, 17–28.

11. Bowen, D. E. and Lawler, E. E. III (1992). Op. cit.

12. Bowen, D. E. and Lawler, E. E. III (1992). Op. cit., p. 36.

13. Berry, L. L., Parasuraman, A. and Zeithamel, V. A. (1994). Improving service quality in America: lessons learned. Academy of Management Executive, 8 (2), 32–52.

14. Silvestro, R., Fitzgerald, L., Johnston, R. and Voss, C. (1992). Towards a classification of service processes. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 3 (3), 62–75.

15. Hallowell, R. (1996). Southwest Airlines: a case study linking employee needs satisfaction and organizational capabilities to competitive advantage. Human Resource Management, 35 (4), 513–34.

16. Berry, L. L. (1995). On Great Service. New York: The Free Press.

17. Berry, L. L. (1995). Op. cit.

18. Hartline, M. D. and Ferrell, O. C. (1996). The management of customer contact service employees: an empirical investigation. Journal of Marketing, 60 (October), 52–70.

19. Martin, C. L. (1996). Editorial: How powerful is empowerment. The Journal of Services Marketing, 10 (6), 4–5.