chapter seven

Innovation and internal

marketing

Introduction

New products are central to corporate growth and prosperity. An estimated 40 per cent of sales come from new products1. Providing value and winning customers has, over time, remained the major challenge. To do this, companies must quickly and accurately identify changing customer needs and wants, develop more complex products to satisfy those needs, provide higher levels of customer support and service, while also utilizing the power of information technology in providing greater functionality, performance and reliability. Improved innovation is one of the major strategic ways of making this happen.

Unfortunately, as Cooper et al.2 note:

![]() one product concept out of seven becomes a commercial success, and only one project in four results in a winner;

one product concept out of seven becomes a commercial success, and only one project in four results in a winner;

![]() roughly half of the resources that industry devotes to product innovation is spent on failures and killed projects;

roughly half of the resources that industry devotes to product innovation is spent on failures and killed projects;

![]() 63 per cent of executives are 'somewhat’ or ‘very disappointed’ in the results of their firms’ new product development (NPD) efforts;

63 per cent of executives are 'somewhat’ or ‘very disappointed’ in the results of their firms’ new product development (NPD) efforts;

![]() new products face a 35 per cent failure rate at launch.

new products face a 35 per cent failure rate at launch.

This highlights the need to take great care when attempting to implement a product development system within an organization. It is important to ensure that the NPD framework interfaces well with existing processes and that it is designed to meet the objectives for which it is being implemented. Also, as organizations evolve, it is imperative that their NPD framework also evolves in a manner that continues to support strategic repositioning and growth objectives.

Notwithstanding the problems, the potential for large benefits from innovation has led it to be increasingly perceived as one of the most important processes within organizations3 . For many companies, success in innovation is through development of a superior NPD framework4. This reliance and focus on a strong innovation capacity is reinforced by research that shows a strong correlation between new product success and a company's health5. Indeed, NPD frameworks are increasingly seen as an important source of competitive advantage6. However, the development and implementation of an NPD framework is by no means simple, nor a guarantee for new product success. In fact, no one best way has been found to organize innovation7, so it comes as no surprise that the causes of new product success and failure often can be traced back to the NPD framework.

Research studies8 have found that:

![]() the technical knowledge, motivational abilities and skills of the project manager are correlated with NPD success and failure;

the technical knowledge, motivational abilities and skills of the project manager are correlated with NPD success and failure;

![]() project manager styles and authority patterns (degree of delegation, formality, etc.) affect product success and failure;

project manager styles and authority patterns (degree of delegation, formality, etc.) affect product success and failure;

![]() proficiencies in executing the various stages of NPD processes (concept, development, prototyping, etc.) frequently affect outcomes;

proficiencies in executing the various stages of NPD processes (concept, development, prototyping, etc.) frequently affect outcomes;

![]() the amount and quality of the technical, marketing and management skill applied to the NPD process are also important;

the amount and quality of the technical, marketing and management skill applied to the NPD process are also important;

![]() the degree of ‘integration’ between the commercial and technical entities is correlated with new product success and failure.

the degree of ‘integration’ between the commercial and technical entities is correlated with new product success and failure.

Further clarification around success factors in NPD was offered by Cooper9 and is summarized below:

![]() a strong market orientation;

a strong market orientation;

![]() an in-depth understanding of user needs and wants;

an in-depth understanding of user needs and wants;

![]() a unique or superior product, i.e. a product with a high performance to cost ratio;

a unique or superior product, i.e. a product with a high performance to cost ratio;

![]() a strong market launch, backed by significant resources devoted to the selling/promotion effort;

a strong market launch, backed by significant resources devoted to the selling/promotion effort;

![]() an attractive market – a high demand and a large growing market;

an attractive market – a high demand and a large growing market;

![]() synergy in a number of areas, including technology and marketing;

synergy in a number of areas, including technology and marketing;

![]() top management support;

top management support;

![]() good internal and external communications.

good internal and external communications.

In a more recent analysis, Griffin10 identified successful firms from lower performers in their:

![]() execution of a commonly agreed to and disciplined NPD process;

execution of a commonly agreed to and disciplined NPD process;

![]() cultivation of a supportive organization and infrastructure for NPD;

cultivation of a supportive organization and infrastructure for NPD;

![]() setting of a clear innovation agenda and management of the portfolio of projects in aggregate.

setting of a clear innovation agenda and management of the portfolio of projects in aggregate.

Proficiency in the performance of NPD activities increases the likelihood of new product success. Proficiency in development and marketing produces the largest increase in project success. By improving performance of key NPD activities under hostile environmental conditions, a company greatly increases the likelihood of success for a new launch.

Benefits of managing for improved innovation

Three major benefits are derived from improving the new product development process. These are outlined below.

Reduced product development costs

Over the course of a new product development project, costs generally increase at an accelerated rate as the product moves towards commercialization11. Due to accelerating costs over the NPD process, it is important to eliminate failures early before they lead to a major loss in investment12

It is estimated that, between the design and manufacturing stage, about 85 per cent of a product's costs can be determined at a point when only 10 per cent of the cost is expended13. This corresponds closely with the work by Pawar et al.14, who found that 80 per cent of a product's cost is committed during the design phase, whereas design itself only absorbs 8 per cent of incurred costs. Managing this process properly means ensuring only those products that stand a reasonable chance of being commercially successful will receive funding. This capability was demonstrated by Colgate-Palmolive, who saw a drop in the number of products that reached the prototype stage from 50 to 20 per cent once an NPD framework had been adopted and implemented. Consequently, the levels of funding applied to programmes which are killed later is reduced, resulting in an improved return on the overall R&D available.

The likelihood of missing key steps, which may require expensive rework or have an impact on cycle time, can also be avoided by providing a roadmap defining tasks and deliverables. With improved clarity of purpose comes the ability to more effectively plan activities and allocate resources. This helps in identifying and allowing opportunities for concurrent activity, while also avoiding any potential functional bottlenecks. The introduction of significant functional improvements offering operational efficiencies (such as DFX techniques) also helps in this effort.

New product development frameworks also contribute to improved levels of planning and decision making by encouraging information to be gathered from all key functions and forcing an evaluation at key milestones within the project to focus the attention on the quality of execution.

The whole focus of the reduction in product development cost is to drive out any unnecessary cost of quality. This is achieved primarily through improved execution, achieved by providing greater stability to the organizational linkages or offering accurate information to guide planning and decision making. Additionally, improved product development productivity is achieved through shorter development cycles and reduced levels of waste. As a consequence, projects with a decreased development lead-time are less expensive (-33 per cent), while those products with higher development lead-time are more expensive to develop (+400 per cent)15

Time to market

Product development, if accelerated, can give rise to benefits such as establishing dominant designs, jumping ahead of the learning curve, realizing higher profit margins, incorporating new technical advances sooner, or influencing and setting industry standards16

The time employed in new product development is determined by the efficiency of the information process, the levels of uncertainty in development and the amount of effort needed to combine all information elements17. It is therefore not enough to automate the shop floor. For effective NPD, the entire design–manufacturing process must be addressed. A faster but inefficient organization is likely to produce a large volume of wastage with defective goods and poor service, resulting in a devastating effect on the bottom line of the organization18

Apart from the external advantages, companies adopting NPD frameworks can realize a number of internal benefits19

![]() rapid generation of economies of learning with lower overhead and labour costs;

rapid generation of economies of learning with lower overhead and labour costs;

![]() more information sharing and problem solving across the organization;

more information sharing and problem solving across the organization;

![]() higher quality of goods and services;

higher quality of goods and services;

![]() lower requirements of working capital;

lower requirements of working capital;

![]() less need for engineering and design changes due to environmental variations.

less need for engineering and design changes due to environmental variations.

New product advantages

The ability to satisfy identified customer needs and wants, by definition, requires an organization to be capable of developing new products effectively and efficiently. Regardless of the types of new products introduced by a company, one thing is clear: the rewards for the development and successful launch of a new product can be significant. For example:

![]() Seven hundred US organizations between 1976 and 1981 stated that 22 per cent of profits and 28 per cent sales growth came from new products.

Seven hundred US organizations between 1976 and 1981 stated that 22 per cent of profits and 28 per cent sales growth came from new products.

![]() Fifty-six per cent of all products that actually get launched are still on the market 5 years later. Other studies estimate the long-term success rate of new products at 65 per cent.

Fifty-six per cent of all products that actually get launched are still on the market 5 years later. Other studies estimate the long-term success rate of new products at 65 per cent.

![]() The companies that lead their industries in profitability and sales growth get 49 per cent of their revenues from products developed over the past 5 years. The least successful get only 11 per cent from new products.

The companies that lead their industries in profitability and sales growth get 49 per cent of their revenues from products developed over the past 5 years. The least successful get only 11 per cent from new products.

![]() According to a 1982 study by Booz, Allen & Hamilton, successful organizations are likely to derive one-third of their profits from new products20

According to a 1982 study by Booz, Allen & Hamilton, successful organizations are likely to derive one-third of their profits from new products20

Those firms that do not keep their NPD practices up to date suffer marked competitive disadvantage. To remain competitive, ‘Best In Class’ firms employ the basic attributes of an effective NPD framework, but continue to show evolutionary improvements on multiple fronts to retain their lead. Consequently, the following advantages can be gained:

![]() improved productivity through upgrades and advancements in technology;

improved productivity through upgrades and advancements in technology;

![]() improved competitive positioning (allowing a thought leadership profile);

improved competitive positioning (allowing a thought leadership profile);

![]() improved ability to penetrate new markets, set rules for existing markets and adjust segmentation criteria, thus adversely affecting competitive reaction;

improved ability to penetrate new markets, set rules for existing markets and adjust segmentation criteria, thus adversely affecting competitive reaction;

![]() improved defence against competitive attacks (shoring up defences through offering flexible configurations or a full product family, thus preventing weaker opponents building up a distribution capability);

improved defence against competitive attacks (shoring up defences through offering flexible configurations or a full product family, thus preventing weaker opponents building up a distribution capability);

![]() ensuring a highly skilled work force is retained and motivated to proceed;

ensuring a highly skilled work force is retained and motivated to proceed;

![]() reducing business risks by having less dependence for revenue and margins on outdated components;

reducing business risks by having less dependence for revenue and margins on outdated components;

![]() stimulating an environment of creativity and innovation that allows companies to compete;

stimulating an environment of creativity and innovation that allows companies to compete;

![]() reduced inventory required (and costs) due to the ability to apply new technology (replace rather than fix).

reduced inventory required (and costs) due to the ability to apply new technology (replace rather than fix).

Evolution of innovation process management systems

Diverse approaches to managing innovation have been attempted over the years, beginning with rudimentary efforts to grapple with technology to sophisticated and encapsulating complex systems of management. Fortunately, these approaches can be categorized into fairly distinct evolutionary phases or generations of development. Rothwell21 distinguishes five generations in the evolutionary development of innovation systems. These development phases are informative in that they help to define the likely trajectory for future progress in the management of innovation.

The first-generation innovation process (1950s to mid 1960s)

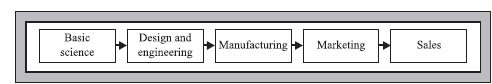

This first generation, or technology push, concept of innovation (Figure 7.1) assumed that ‘more R&D in’ resulted in ‘more successful new products out’. With one or two notable exceptions, little attention was paid to the transformation process itself or the role of the marketplace in the process.

Figure 7.1 Technology push (first generation). Source: Rothwell, R. (1994). Towards the fifth-generation innovation process. International Marketing Review, 11 (1), 7–31.

The second-generation innovation process (mid 1960s to early 1970s)

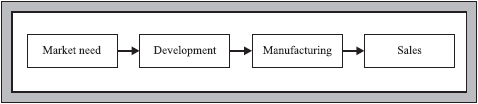

Perceptions of the innovation process began to change as the business environment began to move toward emphasizing demand side factors, i.e. the marketplace. This resulted in the emergence of the second generation or ‘market pull’ (sometimes referred to as the ‘need pull’) model of innovation shown in Figure 7.2. This is a simple sequential model, in which the market is the source of ideas for directing R&D. R&D merely plays a reactive role in the process.

One of the primary dangers of following this model was that it could easily lead companies to neglect long-term R&D programmes and become locked in to a regime of technological incrementalism. Companies using this approach were being directed to adapt existing products to meet changing user requirements along maturing performance trajectories. By doing so, they ran the risk of being outstripped by radical innovators.

The third-generation innovation process (early 1970s to mid 1980s)

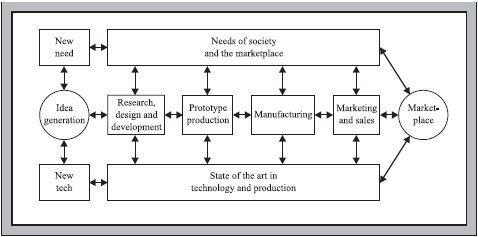

The technology push and need pull models of innovation are polar examples of a more general process. This led to the development of a third interactive or ‘coupling’ generation. The coupling model (Figure 7.3), according to Rothwell, can be regarded as:

‘A logically sequential, though not necessarily continuous process, that can be divided into a series of functionally distinct but interacting and interdependent stages. The overall pattern of the innovation process can be thought of as a complex net of communication paths, both intra-organisational and extra-organisational, linking together the various in-house functions and linking the firm to the broader scientific and technological community and to the marketplace. In other words the process of innovation represents the confluence of technological capabilities and market-needs within the framework of the innovating firm.’ 22

The third-generation innovation model was seen by most western companies, certainly up to the mid 1980s or so, as presenting best practice. It was still essentially a sequential process, but with feedback loops.

Rothwell23 notes two sets of issues for success, namely project execution and corporate level factors:

Figure 7.2 Market pull (second generation). Source: Rothwell, R. (1994). Towards the fifth-generation innovation process. International Marketing Review, 11 (1), 7–31.

Project execution factors

![]() good internal and external communication – accessing external know-how;

good internal and external communication – accessing external know-how;

![]() treating innovation as a corporate-wide task – effective inter-functional co-ordination, good balance of functions;

treating innovation as a corporate-wide task – effective inter-functional co-ordination, good balance of functions;

![]() implementing careful planning and project control procedures – high equality up-front analysis;

implementing careful planning and project control procedures – high equality up-front analysis;

![]() efficiency in development work and high quality production;

efficiency in development work and high quality production;

![]() strong marketing orientation – emphasis on satisfying user needs, development emphasis on creating user value;

strong marketing orientation – emphasis on satisfying user needs, development emphasis on creating user value;

![]() providing a good technical and spares service to customers – effective user education;

providing a good technical and spares service to customers – effective user education;

![]() effective product champions and technological gatekeepers;

effective product champions and technological gatekeepers;

Figure 7.3 The ‘coupling’ model of innovation (third generation). Source: Rothwell, R. (1994). Towards the fifth-generation innovation process. International Marketing Review, 11 (1), 7–31.

![]() high quality, open-minded management – commitment to the development of human capital;

high quality, open-minded management – commitment to the development of human capital;

![]() attaining cross-project synergies and inter-project learning.

attaining cross-project synergies and inter-project learning.

Corporate level factors

![]() top management commitment and visible support for innovation;

top management commitment and visible support for innovation;

![]() long-term corporate strategy with associated technology strategy;

long-term corporate strategy with associated technology strategy;

![]() long-term commitment to major projects (patient money);

long-term commitment to major projects (patient money);

![]() corporate flexibility and responsiveness to change;

corporate flexibility and responsiveness to change;

![]() top management acceptance of risk;

top management acceptance of risk;

![]() innovation-accepting, entrepreneurship-accommodating culture.

innovation-accepting, entrepreneurship-accommodating culture.

These factors show that success or failure can rarely be explained in terms of one or two factors only. Rather, explanations are usually multifaceted. In other words, success is rarely associated with performing one or two tasks brilliantly, but with doing most tasks competently and in a balanced and well co-ordinated manner. At the very heart of the successful innovation process are ‘key individuals’ of high quality and ability, people with individual flair and a strong commitment to innovation.

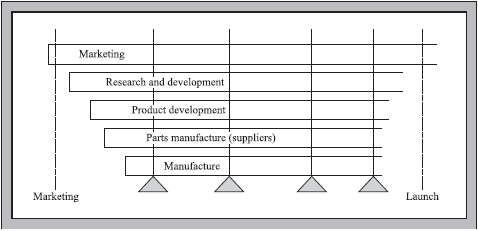

Fourth-generation innovation process (early 1980s to early 1990s)

With shortening product life cycles, speed of development became an increasingly important weapon in competitive battles. It was during this period that Western companies began to notice the remarkable performance of Japanese innovators in world markets. It soon transpired that the Japanese innovators possessed system characteristics that enabled them to innovate more rapidly and efficiently than their Western counterparts. Two striking features of Japanese innovation (the basis of the fourth-generation innovation model) were integration and parallel development. The Japanese not only integrated suppliers into the new product development process at an early stage, but also were able to simultaneously integrate the activities of the different functional parties, working on the innovation (in parallel) rather than sequentially (in series). This came to be called the ‘rugby’ approach to new product development. An illustrative example of the fourth generation as practised in Nissan is given in Figure 7.4. Many leading Western companies are even today grappling to come to terms with the essential features of this fourth-generation process.

Figure 7.4 Example of the integrated (fourth-generation) innovation process. Source: Rothwell, R. (1994). Towards the fifth-generation innovation process. International Marketing Review, 11 (1), 7–31.

The fifth-generation innovation process

By the late 1990s, there was a strong trend toward the practice of speed to market. Organizationally faster development speed and greater efficiency mean creating tighter internal and external linkages and using a higher level of sophisticated electronic toolkits to facilitate the innovation process. Taken together, these changes of practice represent a shift towards the fifth-generation innovation process. The fifth generation involves enhanced systems integration and networking. It is essentially a development of the fourth-generation (parallel, integrated) process via higher utilization of technology to induce integrated and networked product development.

The characteristics of the fifth generation (5G), in terms both of underlying strategic elements and the primary enabling factors, are:

Underlying strategy elements

![]() time-based strategy (faster, more efficient product development);

time-based strategy (faster, more efficient product development);

![]() development focus on quality and other non-price factors;

development focus on quality and other non-price factors;

![]() emphasis on corporate flexibility and responsiveness;

emphasis on corporate flexibility and responsiveness;

![]() customer focus at the forefront of strategy;

customer focus at the forefront of strategy;

![]() strategic integration with primary suppliers;

strategic integration with primary suppliers;

![]() strategies for horizontal technological collaboration;

strategies for horizontal technological collaboration;

![]() electronic data processing strategies;

electronic data processing strategies;

![]() policy of total quality control.

policy of total quality control.

Primary enabling features

![]() greater overall organization and systems integration:

greater overall organization and systems integration:

– parallel and integrated (cross-functional) development process;

– early supplier involvement in product development;

– involvement of leading-edge users in product development;

– establishing horizontal technological collaboration where appropriate;

![]() flatter, more flexible organizational structures for rapid and effective decision making:

flatter, more flexible organizational structures for rapid and effective decision making:

– greater empowerment of managers at lower levels;

– empowered product champions/project leaders/teams;

![]() fully developed internal databases:

fully developed internal databases:

– effective data sharing systems;

– product development metrics, computer-based heuristics, expert systems;

– electronically assisted product development using 3D-CAD systems and simulation modelling;

– linked CAD/CAE systems to enhance product development flexibility and product manufacturability;

![]() effective external data link:

effective external data link:

– co-development with suppliers using linked CAD systems;

– use of CAD at the customer interface;

– effective data links with R&D collaborators.

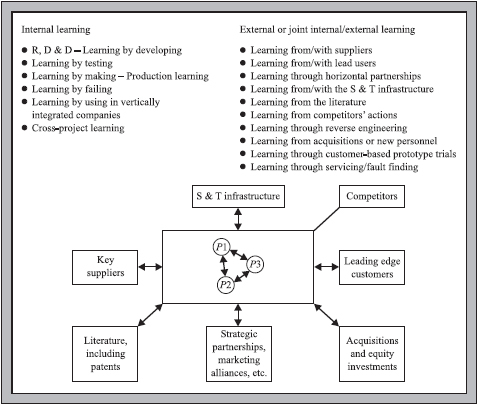

The most radical feature of 5G is that it represents a more comprehensive process of electronification of innovation across the whole innovation system. The electronification process has a positive side-effect: it increases the potential for know-how accumulation and learning (Figure 7.5). Electronic product development tools allow efficient real-time handling of information across the whole system of innovation. In sum, 5G is a process of parallel information processing, which brings together the traditional informal face-to-face human interaction with electronic information processing and interaction. In general, electronic systems help to leverage knowledge.

Whatever the outcome, it seems probable that it is those companies that invest in mastering the 5G process today who will be the leadingedge innovators of tomorrow.

Figure 7.5 Innovation as a process of know-how accumulation. Source: Rothwell, R. (1992). Successful industrial innovation: critical factors for the 1990s. R&D Management, 22 (3), 221–38.

New product development – a generic framework

Having sketched the evolutionary trajectories, we present a detailed discussion of a generic model that constitutes the foundation of modern day practice.

A number of NPD frameworks have been developed to satisfy the needs of different organizations operating in different markets. Their goal is to bring products to market on time, to optimize business results by reducing cycle-times and costs, and to manage the programmes according to agreed business plans over the products’ life cycle. The majority of these NPD frameworks possess a number of similar important characteristics, which when executed in a balanced and effective manner can significantly improve NPD performance. These characteristics generally include:

![]() Use of a ‘Structured Development Process’, providing the ‘rules of the game’ and describing entry and exit criteria between key programme milestones, primary tasks, schedules and resource assignments.

Use of a ‘Structured Development Process’, providing the ‘rules of the game’ and describing entry and exit criteria between key programme milestones, primary tasks, schedules and resource assignments.

![]() A team of senior executives, called a ‘Review Board’, who provide oversight of the programmes by resolving cross-project issues, setting project priorities, resolving issues and make GO/KILL decisions.

A team of senior executives, called a ‘Review Board’, who provide oversight of the programmes by resolving cross-project issues, setting project priorities, resolving issues and make GO/KILL decisions.

![]() Use of ‘Realization Teams’ (cross-functional execution teams), operating under a product ‘champion’ and reporting to the assigned senior management oversight board.

Use of ‘Realization Teams’ (cross-functional execution teams), operating under a product ‘champion’ and reporting to the assigned senior management oversight board.

![]() ‘Phase or Stage/Gate Reviews’ at major development milestones, when funding, resources and project schedules are approved or rejected by the Review Board.

‘Phase or Stage/Gate Reviews’ at major development milestones, when funding, resources and project schedules are approved or rejected by the Review Board.

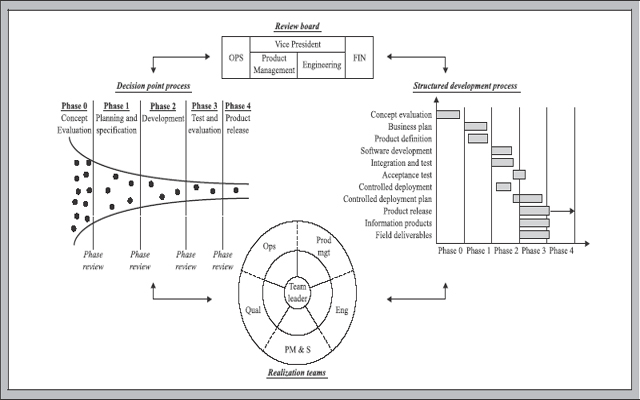

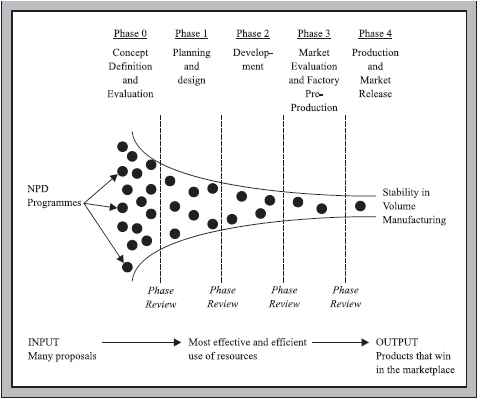

The activities are generally organized into distinct phases that are carried out sequentially by the Realization Teams and separated by ‘Stage/Gate’ reviews held by the Review Board. This is illustrated below using a ‘Best in Class’ NPD Framework called ‘PACE’ (Product And Cycle-time Excellence) devised by the consultants PRTM24 (see Figure 7.6).

Each component is discussed in more detail next.

Structured Product Development Process (SDP)

In many companies, the way products are developed is completely unstructured. There is no consistent terminology; each project team uniquely defines its activities, even though many are similar. This need for additional structure is demonstrated by an associated high cost of quality demonstrated by the following symptoms25

![]() Inconsistent terminology and definitions, leading to garbled or confused hand-offs (up to 39 per cent has been estimated), causing wasted effort, misdirected work and demanding increased numbers of clarification meetings.

Inconsistent terminology and definitions, leading to garbled or confused hand-offs (up to 39 per cent has been estimated), causing wasted effort, misdirected work and demanding increased numbers of clarification meetings.

![]() Inability to estimate resource requirements and schedules, resulting in sub-optimal planning and execution in support of programmes considered vital to the company.

Inability to estimate resource requirements and schedules, resulting in sub-optimal planning and execution in support of programmes considered vital to the company.

![]() Excessive task interdependence, resulting in complex and inefficient communication channels, and plans being made disjointedly between groups and a poor understanding of responsibilities. In some instances, 42 per cent of work has been repeated because of upstream changes, which have occurred due to late customer input, something being overlooked or errors in specifications.

Excessive task interdependence, resulting in complex and inefficient communication channels, and plans being made disjointedly between groups and a poor understanding of responsibilities. In some instances, 42 per cent of work has been repeated because of upstream changes, which have occurred due to late customer input, something being overlooked or errors in specifications.

![]() Attention focused on fire fighting. In some cases, at least 48 per cent of development work has been identified as fire fighting and caused by unplanned work, which appears unexpectedly but requires immediate attention.

Attention focused on fire fighting. In some cases, at least 48 per cent of development work has been identified as fire fighting and caused by unplanned work, which appears unexpectedly but requires immediate attention.

Figure 7.6 PRTM's PACE NPD framework. Source: Anthony, Shapiro and McGrath (1992). Product Development: Success Through Product & Cycle-time Excellence (PACE). London: Butterworth-Heinemann

Structured Development Processes (SDP) offers a framework consisting of terms that describe what needs to be done in development and allows them to be consistently applied across all projects. For this, the SDP must be used uniformly across the company and compliance must be mandatory. In this way, it forms part of the organizational culture. ‘Best in Class’ companies create guidelines around the SDP to ensure major tasks are performed across all projects and ensure mistakes, once identified, are not repeated. The clarity offered in these documents concerning key cross-functional linkages and responsibilities ensures an effective overlap of activities, improved hand-offs between functional groups, setting of realistic and more achievable schedules, and improved planning and control.

The major activities commonly seen to be executed within a typical NPD framework, after the original idea has been screened and accepted by management, are to:

![]() develop and test the product concept;

develop and test the product concept;

![]() formulate a marketing strategy;

formulate a marketing strategy;

![]() analyse the impact on the business in terms of sales, cost and profit projections;

analyse the impact on the business in terms of sales, cost and profit projections;

![]() develop the concept into a product;

develop the concept into a product;

![]() market test the product and time its design and market strategy;

market test the product and time its design and market strategy;

![]() build and launch the product.

build and launch the product.

The SDP offers the guidance to execute these activities in the company in an effective and co-ordinated fashion.

Realization Teams

The secret to successful product development teams lies in organizing them to achieve effective communication, co-ordination and decision making. Many different organization structures exist in support of different companies’ business objectives. Predominantly, organizations employ hierarchical and bureaucratic structures to implement. Unfortunately, with extensive rules and procedures in place, many of the different departments operate almost independently of each other. With the increased importance placed in better developing new products, many companies attempt to impose their functional organization onto the NPD framework, resulting in such models as the serial ‘Relay Race’, iterative ‘Ping-Pong’ and parallel ‘Rugby’ approaches – with varying degrees of success.

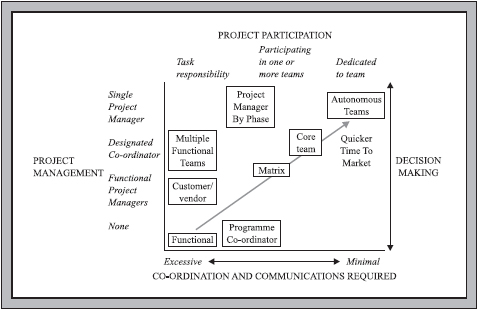

A number of studies have been conducted to identify the most effective team structure to support NPD activities, resulting in the identification of many different approaches to team composition and the associated authority which can be employed (see Figure 7.7).

Work by Corey and Starr26, in their survey of 500 manufacturing firms, reported that core teams or autonomous (Realization) teams operating in a matrix organization were most successful amongst all other alternatives. Use of traditional functional teams produces the lowest success in controlling cost, meeting schedules, achieving technical performance and overall results27. The value in using empowered senior cross-functional teams to drive such programmes is one that is not lost on the majority of companies. Trygg28 found ‘96 per cent of all groups who had halved product development times employed the use of crossfunctional teams’. A further contributing factor to the success of these teams was the extent to which leadership is provided by a ‘product champion’29.

These teams are key enablers of the NPD framework. They facilitate a change in focus within the company away from functional and towards project-specific goals – something which is supported by the high level of budget control they are assigned. Their accountability and responsibility for project-related goals fosters a greater sense of ownership and commitment, and the improved communications result in a highly effective and dedicated team.

Figure 7.7 Project team construction: empowerment and effectiveness. Source: Anthony, Shapiro and McGrath (1992). Product Development: Success Through Product & Cycle-time Excellence (PACE). London: Butterworth-Heinemann.

The important message to take from this is that team approaches produce lower production and labour costs and more committed employees. Indeed, self-managed cross-functional teams are seen as the keystone to leaner and more flexible organizations capable of managing intensifying competitive pressures and the inexorable acceleration of technology. This is also seen as the logical means to generate more creative, less problem-riddled solutions, faster.

Review Boards

Senior management involvement is generally channelled through formally designated Review Boards. These bodies can also be referred to as Product Approval Committees (PAC), Resource Boards or New Product Executive Groups. This group is designated within the company to approve and prioritize new product development investments. Specifically, it has the authority and responsibility to:

![]() initiate new product development projects;

initiate new product development projects;

![]() cancel and re-prioritize projects;

cancel and re-prioritize projects;

![]() ensure that products being developed fit the company's strategy;

ensure that products being developed fit the company's strategy;

![]() allocate development resources.

allocate development resources.

Because this is a decision-making group, it should remain small, and typically include the ‘Chief Executive Officer’ (CEO), ‘Chief Operating Officer’ (COO) or General Manager, and the Heads of the Marketing, Engineering, Finance and Operations areas. In this capacity, each would be expected to dedicate around 10–15 per cent of their time on oversightrelated activities. The specific roles expected to be performed by these members generally include:

![]() Establish the vision. Setting strategy by establishing a vision for their company's products. With this clear vision, the entire company can execute development activities to achieve it.

Establish the vision. Setting strategy by establishing a vision for their company's products. With this clear vision, the entire company can execute development activities to achieve it.

![]() Make decisions. Senior management needs to review the right information at the right time to make the right decisions.

Make decisions. Senior management needs to review the right information at the right time to make the right decisions.

![]() Cultivate the product development process. A superior process can be a source of competitive advantage. Supporting a common process smoothens the execution of product development activities.

Cultivate the product development process. A superior process can be a source of competitive advantage. Supporting a common process smoothens the execution of product development activities.

![]() Motivate. Successful motivation and leadership in product development require that senior management has already achieved respect in the three previous roles.

Motivate. Successful motivation and leadership in product development require that senior management has already achieved respect in the three previous roles.

![]() Recruit the best development staff. This is especially important when trying to secure individuals with specific technical skill or expertise.

Recruit the best development staff. This is especially important when trying to secure individuals with specific technical skill or expertise.

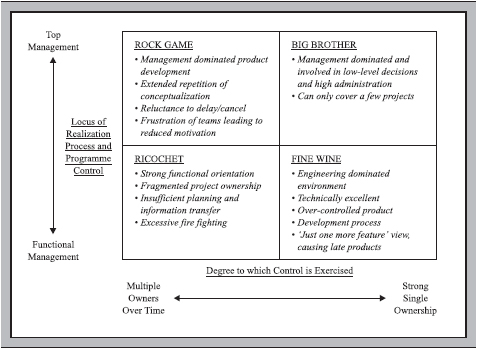

It is important that the balance is achieved between the Review team's authority and the empowerment exercised by the Realization Teams. This is a view supported by Anthony and McKay30, who state: ‘the foundation for leadership in NPD is based on balancing product development and process control and its associated information needs between top management (responsible for the strategic direction and resource allocation) and the development teams (responsible for conceptualizing, designing, testing, manufacturing, launching and screening new products)’. The issue of project and resource management in NPD is an important one and can lead to the control of an NPD framework being unbalanced (being either insufficient), overbearing, inappropriate or based on incomplete information. Two dimensions in determining this balance are:

![]() locus of control between top management and cross-functional execution teams;

locus of control between top management and cross-functional execution teams;

![]() degree to which the control is exercised.

degree to which the control is exercised.

The symptoms that can be expected from an unbalanced NPD framework, by applying these two dimensions, are shown in Figure 7.8

Anthony and McKay found that improvements due to balancing the NPD framework can be dramatic – frequently a 50 per cent reduction in cycle-time can be achieved within the first year. Other benefits include better products, lower development costs, improved predictability and the ability to handle more development projects concurrently.

Phase review process

All companies have a decision-making process for new products, although some may not recognize it as an explicitly defined process. In this instance, decision making can become unreliable and consequently introduce significant delays to product development programmes. This can be overcome by applying a well-defined and effective phase review process.

The phase review process drives the other product development processes. It is the process whereby the Review Board:

Figure 7.8 New product development balance (locus of control and degree to which it is exercised. Source: Anthony, M. T. and McKay, J. (1992). ‘FROM EXPERIENCE: balancing the product development process: achieving Product and Cycle-time Excellence in high technology industries. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 9, 140–7.

![]() makes the difficult strategic-level product decisions;

makes the difficult strategic-level product decisions;

![]() allocates resources to product development efforts;

allocates resources to product development efforts;

![]() provides direction and leadership to the project teams; and

provides direction and leadership to the project teams; and

![]() empowers the Realization Teams to develop the programme on a phase-by-phase basis.

empowers the Realization Teams to develop the programme on a phase-by-phase basis.

These decisions are made through approval at the conclusion of specific phases in the development effort, and are generally guided by a list of deliverables and milestones that are expected to be completed in support of a GO/NO-GO decision.

The phase review process is intended to cover all significant product development efforts, including all major new product development opportunities. In addition, projects that have a significant impact on multiple functional areas, such as manufacturing, support, sales and marketing, should be included in this process. Very small projects such as minor enhancements are usually managed by a simpler process or grouped and managed as a package.

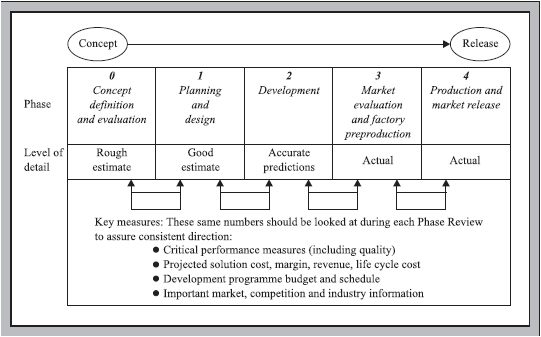

While the NPD process is conceptualized in different ways, many conceptualizations incorporate project review points. Review Boards use these review points to examine projected technical, marketing and financial performance of programmes to determine whether to proceed with developing the new product or to terminate it prior to commercialization. The stage/gate model shown in Figure 7.9 has five stages, although more or less may be employed by different companies. The phase review process can be viewed as a funnel with many ideas entering at the concept phase and, through a series of screenings over the course of development, narrowed to a few appropriately resourced projects with high likelihood of market success. At the conclusion of each phase, a review is held to determine the direction of the project: proceed, cancel or redirect (see Figure 7.9).

In each phase, a number of activities are executed concurrently across a number of different functions. At specific points, these are brought together in the form of specific phase review deliverables that are presented to the Review Board. On the basis of the information provided, the innovation programme will be permitted to proceed to the next phase (with commitments in funding and resources given), given instructions to refocus, or cancelled. This review activity ensures that funded programmes are consistent with the company's strategic and financial goals, and are supported and resourced in a manner that increases the likelihood of success.

Figure 7.9 Funnel approach of new product development frameworks. Source: Anthony, Shapiro and McGrath (1992). Product Development: Success Through Product & Cycle-time Excellence (PACE). London: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Clearly, at the front of this funnel, very little may be known about a concept or the target market to which it is to be applied. As a result, the information to support the opportunity is somewhat rough and incomplete. However, over time and as the programme moves through the funnel, the levels of completeness and accuracy of the supporting information improve. As a result, the Review Board will be able to approve increasing levels of resource to support an opportunity as the quality of information improves over time (see Figure 7.10).

This ability to review programmes and commit resources based on increasing understanding of the opportunity offers an important risk abatement mechanism by allowing undesirable programmes to be cancelled prior to the development phase, when most resources are expended. This is supported by the finding that 80 per cent of a product's cost is committed during the design phase, whereas design only absorbs 8 per cent of incurred costs31

Figure 7.10 Risk abatement in NPD decision points. Source: Pittiglio, Raban, Todd and McGrath (1992). Product and Cycle-time Excellence (PACE) – Revision C, NCR SSSD, February.

Clearly, the contribution NPD frameworks can make to a company is determined by the effectiveness of its decision-making process to identify what opportunities to pursue. This also requires some insight into the interdependencies between programmes and the associated resource allocations. As a result, the definition and application of an effective phase review process should exhibit the following major characteristics:

![]() provide a clear and consistent process for making major decisions on new products and enhancements;

provide a clear and consistent process for making major decisions on new products and enhancements;

![]() empower project teams to execute a project plan;

empower project teams to execute a project plan;

![]() provide the link for applying product strategy to product development;

provide the link for applying product strategy to product development;

![]() provide measurable checkpoints to monitor progress;

provide measurable checkpoints to monitor progress;

![]() establish milestones that emphasize a sense of urgency.

establish milestones that emphasize a sense of urgency.

In fact, current practices indicate that the highest attrition of programmes in the funnel takes place at concept screening, with the second largest number of cancellations taking place in the next, business planning, phase. Consequently, programmes are eliminated much earlier in the NPD process than in the past, resulting in less time and money being spent on a particular idea32. Modern day corporate portfolios of NPD projects are therefore wasting less money on unsuccessful products33

Weaknesses in the innovation management methods

Regardless of the gains to be achieved through an effective NPD framework, there still appears to be much room for improvement. Recent analysis of various NPD frameworks and the programmes being executed within them indicated weaknesses which give cause for concern, and in some cases result in the NPD programmes having a negative impact on the success of the organization34

![]() around 24 per cent of companies who have implemented an NPD framework have reported worse ‘Time to Market’ performance;

around 24 per cent of companies who have implemented an NPD framework have reported worse ‘Time to Market’ performance;

![]() 63 per cent of company executives have stated that they are 'somewhat’ or ‘very’ disappointed in their firms’ new product efforts;

63 per cent of company executives have stated that they are 'somewhat’ or ‘very’ disappointed in their firms’ new product efforts;

![]() additionally, it has been identified that 46 per cent of resources invested in new product programmes are wasted on technical and commercial failures.

additionally, it has been identified that 46 per cent of resources invested in new product programmes are wasted on technical and commercial failures.

Consequently, it is not surprising that this less than startling rate of success has resulted in many studies aimed at identifying associated problems and inefficiencies. In support of this, some studies have shown new product success not to have improved over the last 30 years35

According to work performed by Cooper and Kleinschmidt36, potential problems may arise with the implementation of a new product development process. More bureaucracy and tighter controls can thwart creativity, and slower decision making is a deadly plague for the introduction of any formal process. Indeed, many of the problems identified appear to be caused by implementation-related issues rather than any fundamental failing of the NPD framework.

New developments in managing the innovation process

The discussion thus far has presented a structured innovation process system that currently represents the state-of-the-art process. However, new developments are taking place that are taking the innovation process on towards a more advanced stage. One of the most interesting developments is the iterative model of Hughes and Chafin37. Hughes and Chafin propose a value creation model, which they call the Value Proposition Process (VPP). Such developmental models show great potential to become the new generation approaches to innovation management.

The Hughes and Chafin model of new product development

One means of making this transformation is the Value Proposition Process (VPP). The objectives of this development approach are continuous learning, identifying the certainty of knowledge used for decision making, building consensus and focusing on adding value.

Value Proposition Process

The VPP was designed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of multifunctional project teams through continuous learning, identifying the certainty of knowledge, building consensus, and focusing on adding value to customers and end-users. To fully leverage this process, the organization in which the team operates must have a culture that supports improvement and innovation, is flexible and encourages change.

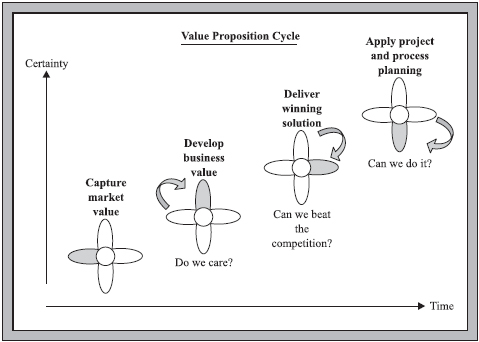

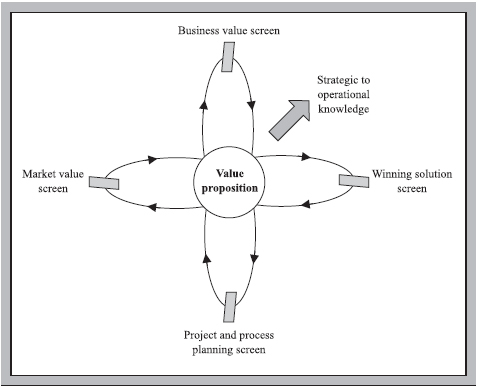

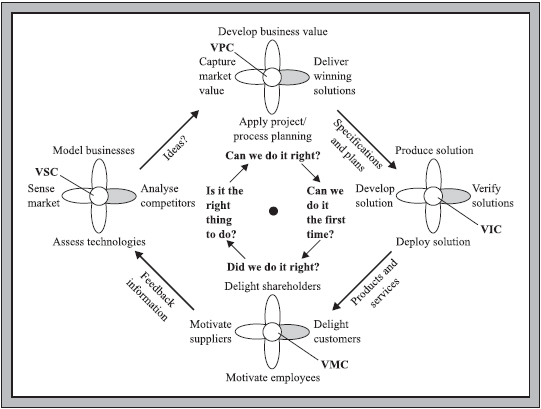

The objective of the VPP is to determine if the organization can convert an idea or an opportunity into a proposition that adds value to the end-users, the company and the value chain. In short, the team must answer a basic question: can we do it right? The VPP consists of a framework of continuous planning cycle, called the Value Proposition Cycle (VPC), and an integrated screening methodology, called the Value Proposition Readiness Assessment (VPRA).

Overview of the Value Proposition Cycle

The VPC comprises four iterative loops, addressing the following activities: capturing the market value of the proposition (does the customer care?); developing the business value (do we care?); delivering a winning solution (can we beat the competition?); and applying project and process planning (can we do it?).

Only a few companies have focused on modelling the relationships between value measures. For example, how is customer satisfaction related to economic value added? How is employee motivation linked to added shareholder value? These questions need to be part of a company's plan for understanding how it adds value. Critical questions to be answered at each loop are as follows:

Figure 7.11 Value Proposition Cycle. Source: Hughes, G. D. and Chafin, D. C. (1996). Turning new product development into a continuous learning process. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 13, 89– 104.

![]() Capture market value – does the customer care?

Capture market value – does the customer care?

![]() Develop business value – do we care?

Develop business value – do we care?

![]() Deliver winning solutions – can we beat the competition?

Deliver winning solutions – can we beat the competition?

![]() Apply project/process planning – can we do it?

Apply project/process planning – can we do it?

The VPC also provides a logical framework for the VPRA methodology. This methodology is based on a series of screens along each loop in the VPC, as shown in Figure 7.12. These screens summarize the success factors for the company. The number of success factors will vary according to the product newness, the amount of risk and the number of product ideas to be screened. New and risky products with a high cost of failure will require more items in the screen. A large line extension can use a reduced set. For a large number of product ideas, a reduced set of items is appropriate for the first screening and then a larger list for the final screening.

Figure 7.12 Integrating VPRA with VPC. Source: Hughes, G. D. and Chafin, D. C. (1996). Turning new product development into a continuous learning process. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 13, 89–104.

The VPP, as a multifunctional teaming methodology to screen ideas, is part of a more encompassing life cycle process. The VPP described focuses on answering the question: can we do it right? However, there is an even more basic question that should be answered first: is it the right thing to do? After the VPP, there is another question: can we do it right the first time? And once the product or service begins to be commercialized, there is an ongoing evaluation question: did we do it right? This question must be answered from the point of view of the four stakeholders: the customer, the employee, the suppliers and the stockholders. A four-loop iterative process can be used to answer each of these questions, forming the portfolio life cycle.

Value Sensing Cycle

The portfolio life cycle process can begin at any point in the life cycle if a product already exists. A really new product would begin at the idea generation stage, known as the Value Sensing Cycle (VSC), which appears in the left in Figure 7.13. This cycle continuously scans the market, the business environment, competition and technology to identify new ideas or opportunities. These ideas are screened and reduced to a manageable few, which are then passed along to the VPC.

Figure 7.13 Continuous life cycle process. Source: Hughes, G. D. and Chafin, D. C. (1996). Turning new product development into a continuous learning process. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 13, 89–104.

Value Introducing Cycle

Once the team and the organization have used the VPC and agreed that they can do it right, the proposition is translated into the final specifications and plans, and fed into the Value Introduction Cycle (VIC). This cycle consists of the fully characterized and highly disciplined process to develop, produce, verify and deploy the solution initially to all target market segments and, over time, any additional market segments. The output of this cycle is products and services, and the required support infrastructure that provides the input for the Value Management Cycle (VMC).

Value Management Cycle

The VMC, at the bottom of Figure 7.13, continuously screens market and business performance to answer the question: did we do it right? The monitoring is from the point of view of our customers, our employees, our suppliers and our stockholders. Critical questions must be answered at each of the four loops in the VMC. Do our customers perceive that they are paying a fair price for the benefit received? Do the project team members feel motivated by what they accomplished? Do we have strong supplier partnerships that will assure our receiving a favoured customer treatment from them? Are we profitable and adding shareholder value? Metrics from each of these four loops are an important part of the CEO's dashboard. Critical feedback from the VMC is linked and fed into the VSC to complete the life cycle.

Macro-models of innovation in organizations

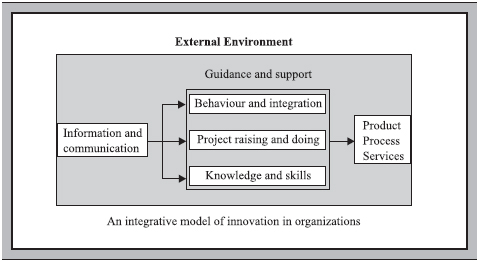

So far, we have looked essentially at micro-level structuring of innovation. Moving to a look at innovation from a higher level of abstraction it is possible to discern the key features of importance. Tang38 captures this overview in suggesting that there are four basic problems. These are:

![]() a human problem of managing attention to the need to innovate;

a human problem of managing attention to the need to innovate;

![]() a process problem in managing new ideas into good currency;

a process problem in managing new ideas into good currency;

![]() a structural problem of managing part–whole relationships;

a structural problem of managing part–whole relationships;

![]() a strategic problem of institutional leadership.

a strategic problem of institutional leadership.

From this, six constructs of innovation are identified:

![]() information and communication;

information and communication;

![]() behaviour and integration;

behaviour and integration;

![]() knowledge and skills;

knowledge and skills;

![]() project raising and doing;

project raising and doing;

![]() guidance and support;

guidance and support;

![]() external environment.

external environment.

Table 7.1 shows the linkage of these constructs to the key concepts. From the six constructs, the associated key concepts and their interactions, a picture of innovation emerges. This is captured in the integrative model of innovation in organizations shown in Figure 7.14.

Table 7.1 Constructs and Concepts for the Model of Innovation in Organizations

Construct: information and communication

Concepts: flow of information and technology, use of information technology, information as source of knowledge and stimulus for innovation.

Construct: behaviour and integration

Concepts: behaviour traits, creative behaviours, motivation to innovate, team roles, cross-functional integration.

Construct: knowledge and skills

Concepts: creativity, intelligence, insights, bisociation, domain-related knowledge and skills, tacit and explicit knowledge, knowledge creation, learning and training.

Construct: project raising and doing

Concepts: opportunity and problem finding, problem solving, product and process development stages, uncertainty reduction.

Construct: guidance and support

Concepts: organization's mission, task, structure, strategy, resources, operation systems. Shared values, leadership style.

Construct: external environment

Concepts: economic rules and innovation, national innovation system, industry structure, culture.

Figure 7.14 Integrative model of innovation.

Accordingly, an organization is encompassed by its external environment. The organization interacts with its external environment through exchanges of information, ideas, goods and services, which include the organization's innovation outputs. At the centre of innovation is the core process of project raising and doing. The results of project raising and doing are new products, processes and services. There are two enablers for this core process. The first is knowledge and skills, and the second is behaviour and integration of individuals, teams and functions. The enablers and the core process influence each other. Positive outcome and progress in the project foster teamwork, whereas a long period of negative results will have the opposite effect. Knowledge is created through doing a project and knowledge so created will reinforce future projects. Information from the external environment, as well as from within the organization, provides inputs and stimulates project raising and doing through the staff of the organization. Availability of information, knowledge and skills, together with creative behaviour and the integration of people in the organization, determine the ability and inclination of staff to raise projects and find innovative solutions. How innovative an organization is depends on the guidance and support, which are defined in terms of the mission, tasks, strategy, systems and resources of the organization. Ultimately, top management underpins the entire innovation process by providing the proper guidance and support in response to the external environment.

Thus far, we have examined thoughts on how innovation management processes have evolved into their current state of being. This is instructive in that it highlights a trajectory of continuous improvement in the approaches and also because it emphasizes the need to build upon the current legacy of systems in place. The effectiveness of the approaches/frameworks is very much contingent upon the specific context a company faces. This means that generic and unquestioned adaptations of frameworks and associated tools are likely to result in failure. Success requires careful understanding of the specific constraints and opportunities, both internal and external to the organization, and a selection and adaptation of an innovation framework that best capitalizes on this context.

In highlighting Hughes and Chafin's model, we present a possible trajectory of development. The Hughes and Chafin model presents an attempt to improve on the currently popular stage/gate system, which is atypical of the 5G innovation systems. The model highlights the need to capture iterative and learning features more thoroughly than earlier innovation processes. It is also driven by a stronger focus on delivering value, and using this as a yardstick of decision making. In contrast, Tang's model highlights the generic challenges facing management of innovation. Taken individually, the models represent moderate improvement on current understanding of the innovation process. Taken together, however, the models are highly representative of the evolutionary trajectory for the next generation of innovation management processes.

Problems in innovation

The major problems to surface in managing innovation are outlined as follows.

Inadequate resources

Shortage of resources (time, money, people) occurs because often:

![]() Too much attention is given to current activities, leading to insufficient efforts for long-term and radical activities. The present versus future conflict is a central source of contradiction on resources.

Too much attention is given to current activities, leading to insufficient efforts for long-term and radical activities. The present versus future conflict is a central source of contradiction on resources.

![]() Resources are too thinly spread out. There is a tendency to consider too broad a range of development directions with limited resources. It is better to focus on fewer directions for better results.

Resources are too thinly spread out. There is a tendency to consider too broad a range of development directions with limited resources. It is better to focus on fewer directions for better results.

![]() Excessive projects. This occurs when there are too many programmes in the innovation product development portfolio. Consequently, people work on too many projects, leading to a tendency to pull expert individuals off one project to fix another one. This can cause serious disruptions in project progress.

Excessive projects. This occurs when there are too many programmes in the innovation product development portfolio. Consequently, people work on too many projects, leading to a tendency to pull expert individuals off one project to fix another one. This can cause serious disruptions in project progress.

Not knowing the customer

Customer orientation is particularly important in successful innovation. It is surprising that many employees, not only scientists and engineers but even marketers, do not understand their customers. The problem is not just a lack of market research making the organization unsure of customer needs, but largely a result of the company's inability to effectively transmit the ‘voice of the customer’ internally. This requires the company to devise ways of correctly exposing employees to customers’ needs.

Unsupportive top management

Lack of commitment from top management strongly dampens innovation. Leadership that leans toward excessive retrospection and possesses attitudes that reinforce ‘we have always done it this way’ deadens radical innovation. Management by signalling and reinforcing the norms of behaviour either encourages or stifles innovation. Innovation begins and ends at the top.

One way to try to combat negative tendencies and turn them into positive ones is to introduce initiatives for creativity. Encouraging open communication and providing creativity training are good techniques for doing just this. However, at times it may be necessary to mandate sharing activities across functional disciplines, for instance through events such as get-together lunches, etc.

Poor decision policies

Poor decision making hinders innovation. This can arise from several sources:

![]() Lack of explicit criteria, which makes justification difficult.

Lack of explicit criteria, which makes justification difficult.

![]() Too many good ideas, which makes setting priorities difficult.

Too many good ideas, which makes setting priorities difficult.

![]() Biases of senior management, especially if toward a single dominant functional area such as marketing or engineering, can actually be very troublesome for well-rounded decisions to be reached.

Biases of senior management, especially if toward a single dominant functional area such as marketing or engineering, can actually be very troublesome for well-rounded decisions to be reached.

![]() Delayed decision making usually builds frustration. Good companies make quick decisions and provide rapid feedback. Decisions that take longer than 2 months often deflate the energy to get things done. The net result – frustration in the recipients.

Delayed decision making usually builds frustration. Good companies make quick decisions and provide rapid feedback. Decisions that take longer than 2 months often deflate the energy to get things done. The net result – frustration in the recipients.

Lack of co-operative behaviour in the project management process

Problems in project management cover areas such as competitive behaviours within the innovation portfolio. These lead to individual teams in the portfolio fiercely battling for resources. One or two individual teams may end up winning out, but the organization as a whole loses.

Additionally, poorly developed and poorly understood organizational goals produce focus on narrow individual team gains. This leads to a lack of synergistic actions and behaviours.

Poor management planning and direction

Vagueness resulting from poor planning leads to frequent changes in priorities. This compounds the problems that already may exist from the chopping and changing of personnel from one project to the next. Consequently, scarce resources are wasted by running in many and often wrong directions.

Internal marketing's role in managing the company for innovation

The role of IM in innovation is multi-faceted, and in this section we will focus discussion on the following areas that directly or indirectly affect a company's success or failure in innovation:

![]() organizational culture

organizational culture

![]() structures, process and context

structures, process and context

![]() employee communications

employee communications

![]() people

people

![]() core competency

core competency

![]() integration.

integration.

Internal marketing plays a role in these because it can reinforce and emphasize aspects that help innovation to take root.

Organizational culture and leadership

Organizational culture embodies a set of deep-seated beliefs and basic assumptions that are shared by members of an organization. Culture works mainly at the unconscious level. It is the lens through which employees and the organization view themselves and their environment. Organizational culture is a representation of the artefacts, actions and norms of the organization. It captures the ‘way of the organization’: how its people dress; how they greet one another; how they interact; how they make decisions; what is important to them; what is not and so on. Organizational culture encompasses symbols, cues and actions, both physical and intangible. Thus, it is possible for astute leadership to emphasize some values and de-emphasize others. This opens up the possibility of moulding cultures that are more conducive to innovation. Whilst the possibility exists, it is nevertheless difficult.

Through its focus on ‘employees’, IM helps the process of identifying current behaviours and probes why they are occurring. Once specific employee behaviour patterns have been established, it is then possible to create specific IM programmes to induce behaviours for enhanced innovation.

Internal marketing indicates to leadership what kind of messages and cues they need to amplify and communicate to get innovation embedded throughout the organization. Internal marketing is a tool that can be used to build in-depth understanding of the workplace environment. Through this understanding, it is possible to identify different employee segment needs. Internal marketing provides managers with insight and tools to customize internal strategies to enhance and improve programme implementation. Internal segmentation is made on the basis of employee behaviours and needs. Clearly, encouragement and direction take on greater meaning if they are focused and more appropriate, rather than one pill for all symptoms. Internal marketing identifies the type of things leadership personally need to promote. For example, if a CEO attends all major meetings, personally gives out awards and tells stories about major sales successes, but does not visit the shop-floor at all, then it suggests a top-down emphasis that places low value on its workers, despite the masquerade of personal involvement. Internal marketing can engage in 360-degree assessments of leadership involvement and objectively assess the weaknesses or contradictions that leadership/managerial actions and behaviours are causing. In this way, IM helps identify gaps in the leadership's armoury. Internal marketing does this by its internal research antennae, which allow it to listen to the pulse of the internal organization.

Internal marketing identifies and compiles stories that exist within the organization of innovation successes and role model individuals. After compiling the critical stories that stress the desired attributes of behaviour for innovation, IM can then package the stories in an appropriate format so that they can be retold throughout the organization. In so doing, IM penetrates the unconscious mind and moves it toward sought-after innovative behaviours. For example, companies like 3M and Hewlett-Packard abound with stories of innovators and innovations. Such stories become part of the organizational folklore, and inventive individuals become heroes and legends. The stories typically make a clear point about a company's culture and are often told to almost every newcomer to the company. This socialization helps to pass on the culture and acts as a powerful guide to actions. Another important feature of culture is that it transcends functional boundaries and its impact. It may look rather nebulous but it is organization-wide and endures over long periods of time.

To the extent that IM can strengthen or change cultural elements that favour innovation, then it can move the company toward innovation.

Structures, processes and context

Internal marketing can be used to examine hierarchies, processes, subprocesses and interfaces, and to assess whether innovation activities are hindered or given priority. For example, it is difficult for a company to successfully pursue ideas to successful commercial outcome if its culture requires multiple levels of approval for all expenditures, and favours strict observance of all rules and procedures. Innovative companies like Hewlett-Packard allow workers up to 15–25 per cent of their work time to pursue innovative projects on their own. This one practice speaks volumes about Hewlett-Packard's cultural attitude to innovation. It signals the importance that the company places, which is stronger than any programmes of ‘forced’ action.

Internal marketing is an approach and a force for empowerment, which attempts to unleash the inventive energy of each and every employee. The culture of a company, coupled with structure, act as primary facilitative agents in this task. Clearly, structures, processes and culture have a far-reaching impact on innovation success. For example, employees may have many excellent innovative ideas, but if the firm's structures and processes discourage or prohibit such ideas from reaching those with the power to evaluate and implement them, then ideas rarely bear fruit.

Internal marketing examines what needs to be done, and by whom. Internal marketing can be used to identify the type of role that innovation agents need to play to execute innovation strategies. These roles can vary from plant (who creates the infectious enthusiasm for a new idea) or sponsor (encouraging ideas from below and nurturing their development) to commander (giving orders and expecting obedience). Each is appropriate under different organizational circumstances and situations. Which role is appropriate for whom is dependent upon the individual's orientation towards the desired goal at that specific moment in time. This links strategic implementation to the specific skills and capabilities of the individual. By implication, this necessitates first knowing the skills and capabilities of each employee before they can be usefully deployed. Some individuals are naturally good at sponsorship, because of their ability to network at many different levels within the organizational hierarchy. Others may be more gifted in development and idea generation. Internal marketing helps in the assessment of these skills for specific innovation projects. This assessment is made more visible because IM looks at a deployment of individual competence from an opportunity cost point of view, which is taken from the organizational viewpoint as well as from the employee's perspective. Moreover, IM is important because it links specific individuals to the strategic context by assessing the strategic sense of specific competence deployment. For instance, while it is usually advocated that the role of sponsor is more appropriate than that of commander in fostering a culture of innovation, this may not necessarily be so. Situations may arise at times of acute crisis when the leader has to push forcefully a particular course of action to ensure survival or break a bottleneck that is unwilling to yield to participative management and sponsorship. Internal marketing assesses the internal context and then assesses the appropriateness of strategic actions and the likely side-effects that may arise. Internal marketing also prepares appropriate internal PR to lessen and ameliorate negative consequences of a specific course of action.

Internal marketing builds an understanding of the organization environment, organizational hierarchy, organization politics and structures. Through this understanding, IM plays an important role in the nurturing of the right environment for innovation. Internal marketing helps reflect on concrete practical experiences. People's behaviour (both managers and employees) has to be evaluated in terms of agreements, guidelines and envisaged objectives, and expectations by others.

Internal marketing helps companies to approach innovation as an ‘open’ system, whereby innovation participants are given control over initiatives and employees are entrusted to organize themselves efficiently39.

In environments of trust, employees are more prepared to do what is necessary, even where it entails breaking existing conventions, rules and routines. The simple maxim used by the US store Nordstrom, ‘use your good judgement in all situations’40, is simple yet a very powerful reminder of the impact that trust can have in energizing the organization toward motivated action.

Employee communication, personalization and space for improvisation

Communication is an indispensable activity in the functioning of all processes, but it is critical in highly cross-functional ones such as innovation. Based on communication, problematic situations can be analysed and interpreted, and solutions can be sought and developed. It is, of course, imperative that the relevant stakeholders are involved in the communication process.