chapter eight

Knowledge management,

learning and internal

marketing

Introduction

More than a decade ago, Peter F. Drucker foretold the coming of the age of the knowledge worker. Workers, in this age, were the critical capital. Whereas machines stay in the factory floor, knowledge goes with the person. The knowledge era began in the 1970s with the advent of IT. It took shape with the birth of personal computers. This technological revolution has given rise to more changes in management practice than any other previous period. With each passing generation, computers have become more powerful, making information storage, processing and transfer widely available. The knowledge economy has made information, and the knowledge of how to use it, more powerful than ever. At the same time, unfortunately, it has reduced the 'shelf-life’ of each piece of new knowledge. Knowledge is the source of competitive advantage, because it is a vessel of human experience and insight capable of potential action.

With the development of the global economy, knowledge management and learning (KM&L) has risen to higher prominence. In this new era, the approach to employees has changed from one treating them as machine-like appendages to intellectual capital possessing strategically valuable and renewable experience.

While clearly knowledge is an asset, it is often not treated as such and is hardly ever consolidated into corporate accounts. Because of such neglect, intellectual capital often walks out of the company and suddenly reappears in the offices of competition. The market value of some corporations can be multiplied several fold. The difference between these and other organizations is in their employees. Individual skills, know-how, relationships and contacts add value and generate wealth. The way organizations tap into their intangible assets can increase the value of these assets to the organization. Employees may possess certain knowledge, but organizations do not benefit from that knowledge unless they put in place an adequate structure and processes to capture, support and enhance it.

In a survey in Fortune magazine1, executives were found to be searching for a new business paradigm. In the 1980s, over 50 per cent of the Fortune 500 underwent some form of restructuring exercise. Executives, however, were not convinced that these new ‘decentralized, lean and mean’ structures were likely to meet the challenges ahead. They believed that they would not be:

![]() Fast enough to match foreign competitors’ product development or identify an opportunity in the marketplace.

Fast enough to match foreign competitors’ product development or identify an opportunity in the marketplace.

![]() Keen enough to deliver higher levels of customer service or achieve leaps in productivity.

Keen enough to deliver higher levels of customer service or achieve leaps in productivity.

![]() Smart enough or sensitive enough to manage a polyglot workforce or satisfy the needs of its best employees.

Smart enough or sensitive enough to manage a polyglot workforce or satisfy the needs of its best employees.

While these companies were busy disfranchising their employees (people with the knowledge) with poorly thought out changes (downsizing, rightsizing and re-engineering), technology was increasing the power of knowledge and information. The emerging knowledge economy was about ideas first, services second and products third. Companies that were busy with de-layering failed to appreciate what the employee actually brings ‘to the table’ in today's workplace. For instance, when older employees are dispensed rather than retrained, it is quite possible that the company is losing persons who hold the experience and share the values that a company desires. Teaching a new young replacement the same can be a costly task. Consequently, the cost of getting ‘lean’ often shows up in poor financials. Why? Because many companies have found they need to re-hire the same employees as expensive external consultants. One of the causes for this myopia is the 500-year-old Venetian ‘double entry’ accounting system, which is unable to assign a value to knowledge that employees possess. Treating people as an undifferentiated resource can levy a heavy penalty. The problem is that companies have yet to come to terms with intellectual capital (IC).

Knowledge management and learning

Knowledge management and learning offer ways to harness the potential of employees. Knowledge and learning are intertwined concepts. New knowledge is the outcome of learning, and new knowledge when it is applied feeds into the building of a higher level of insight and learning.

Organizational learning is a process in which an organization's members actively use data to guide behaviour in such a way as to promote the ongoing adaptation of the organization2. It is a process by which managers become aware of the qualities, patterns and consequences of their own experiences, and develop mental models to understand these experiences3. Knowledge, on the other hand, is closely linked to organizational memory, which allows the organization to call up past events, remember what was done – what worked and what did not work – and avoid the‘reinvent the wheel’ syndrome.

Peter Senge highlighted the link between learning and knowledge in stating: ‘Learning in organizations means the continuous testing of experience, and the transformation of that experience into knowledge – accessible to the whole organization, and relevant to its core purpose’4. Not only does experience need to be continuously tested (with an aim, not just to test), but also the relevant parts of that experience must be shared with appropriate people in the company. Companies renew themselves through processes of organizational learning5. Implanting new knowledge involves innovative behaviour, and learning is the means through which change occurs. Knowledge management (KM) is intertwined with learning. Learning is an essential aspect in examining organizational change processes. Companies are routine-based, historydependent systems that respond to experience. In other words, they are experiential learning systems6. The company's past affects its future capability of change. Learning brings about changes in current routines and institutes new capabilities7.

Change and learning reinforce each other. Change tends to invalidate known answers and so demands continuous learning. New knowledge is attained through learning. Learning generates change, which in turn can again lead to learning, etc. The knowledge–learning cycle can lead to continuous improvement if utilized properly. Learning is more than getting everyone to understand systems and their architectures8. It is also about discerning and managing interrelations. To really embed knowledge and learning in the workplace involves not just developing new capabilities, but also making fundamental shifts in the mindsets of the individual and collective units.

The learning organization is built upon four pillars9:

1 Philosophy (in which vision, values and purpose are important).

2 Attitudes and beliefs (in which there is genuine caring and commonness of aims, and the willingness to change and learn).

3 Skills and capabilities (in which systems thinking is developed, along with a shared commitment).

4 Tools (systems tools) that can be used to learn throughout the organization.

Developing knowledge and learning foundations requires companies to share beliefs, attitudes and vision. In a study of successful learning organizations, it was found that the first principle is the need for a vision, upon which organizational members can base their future learning requirements10. Secondly, this vision must be shared throughout the organization. Peter Senge11notes that one ‘cannot have a learning organization without shared vision’. Without a strong pull toward a common goal, the forces in support of the status quo can be overwhelming. Shared perspectives provide focus and energy for sharing knowledge and learning. ‘It's not what the vision is, it's what the vision does’ that is important12.

Barriers to learning

Barriers to learning or disabilities are an ingrained part of all organizations. Common barriers that can debilitate the transition into a learning organization are13:

![]() ‘I am my position’ (the manager or employee who places loyalty to the job before loyalty to the firm – ‘functional myopia’).

‘I am my position’ (the manager or employee who places loyalty to the job before loyalty to the firm – ‘functional myopia’).

![]() ‘The enemy is out there’ (when the true enemy is almost invariably ‘inside’ the organization).

‘The enemy is out there’ (when the true enemy is almost invariably ‘inside’ the organization).

![]() Illusion of taking charge (when proactivity is really ‘reactiveness’ in disguise).

Illusion of taking charge (when proactivity is really ‘reactiveness’ in disguise).

![]() Fixation on events rather than processes.

Fixation on events rather than processes.

![]() Delusion of learning from experience (is commonplace because we rarely directly suffer the consequences of many of our decisions; there is usually a separation between decision and consequence, allowing us to live the delusion that learning has taken place).

Delusion of learning from experience (is commonplace because we rarely directly suffer the consequences of many of our decisions; there is usually a separation between decision and consequence, allowing us to live the delusion that learning has taken place).

![]() The myth of the management ‘team’.

The myth of the management ‘team’.

Five statements that serve as guideposts as to what a learning organization is and is not are14:

1 It is not just a collection of individuals who are learning.

2 It demonstrates organizational capacity for change.

3 It accelerates individual learning capacity, but also redefines organizational structure, culture, job design and assumptions about the way things are.

4 It involves widespread participation of employees – and often customers – in decision making and information sharing.

5 It promotes systemic thinking and building of organizational memory.

It is a fact that all organizations learn, but only learning organizations consciously learn.

Knowledge management directs and enhances organizational decisions as to how, where and when to create and account for new knowledge. Knowledge management prevents the loss of critical knowledge due to retirement, rightsizing and employee mobility to other firms. When proactively supported by senior management, knowledge management encourages the employee to create, share and benefit from knowledge. The business problem that knowledge management attempts to solve is that often knowledge acquired through experience isn't reused because it isn't shared in a formal way. The ultimate goal of knowledge management is to give the organization a capacity to be more effective every passing day by the gathering of institutional memory, very much like human beings who possess a capacity to become more effective and mature every day with the accumulation of thoughts and memories15.

The implementation of knowledge management is an organizational change process that involves learning and often requires an extensive cultural change. In this process, managers are responsible for shaping organizational culture by advancing knowledge management awareness and values, for the development and deployment of strategy for knowledge, for the development and communication of knowledge management policy, for setting knowledge management goals, and putting in place knowledge management systems and processes.

Different types of KM

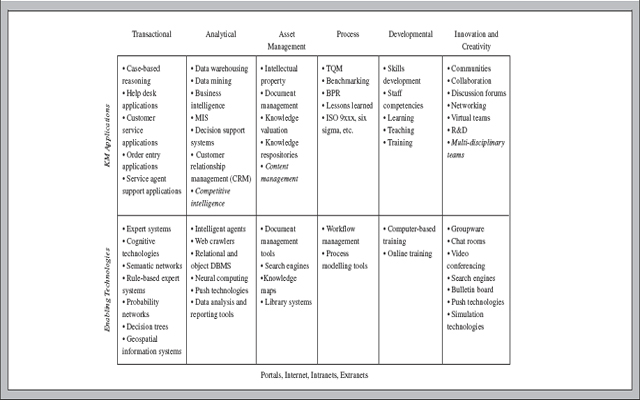

Over time, many different varieties of knowledge management have appeared on the scene. Binney16 puts forward a KM spectrum that usefully covers an extensive range of KM approaches and applications (Figure 8.1).

Transactional KM

In transactional KM, the use of knowledge is embedded in the application of technology. Knowledge is presented to the user of a system in the course of completing a transaction or a unit or work, e.g. entering an order or handling a customer query or problem. An example of transactional KM is case-based reasoning. ‘Case-based reasoning provides a method for representing past situations (cases) and retrieving similar cases when a new problem is input. Given a description of a problem, the system searches for similar known cases. The system asks the user questions (proactively) about the problem to narrow the search for similar problems’17. Other examples of transactional KM include help desk, customer service, order entry and field support applications.

Figure 8.1 Spectrum of knowledge management. Source: Binney, D. (2000). The knowledge management spectrum –understanding the KM landscape. Journal of Knowledge Management, 5 (1), 21–32.

Analytical KM

Analytical KM provides interpretations of, or creates, new knowledge from vast amounts or disparate sources of material. In analytical KM applications, large amounts of data or information are used to derive trends and patterns – uncovering that which is hidden due to the vastness of the source material. It turns data into information, which, if acted on, can become knowledge.

Traditional analytical KM applications such as management information systems and data warehousing analyse the data or information that are generated internally in companies (often by transactional systems). Traditional analytical KM applications focus on customer-related information to assist activities such as product development functions. These are now being complemented by a range of competitive or business intelligence applications that incorporate external sources of knowledge or information. Such competitive intelligence applications are being used to analyse and understand what is happening in their marketplace and assess competitive activity.

Asset management KM

Asset management KM focuses on processes associated with the management of knowledge assets. This involves either:

![]() The management of explicit knowledge assets which have been codified in some way; or

The management of explicit knowledge assets which have been codified in some way; or

![]() The management of intellectual property (IP) and the processes surrounding the identification, exploitation and protection of IP.

The management of intellectual property (IP) and the processes surrounding the identification, exploitation and protection of IP.

Once captured, the assets are made available to people. This element of the spectrum is directly analogous to a library, with the knowledge assets being catalogued in various ways and made available for unstructured access and use.

Knowledge assets are often created as a by-product of ‘doing business’ and are kept for future use. What differentiates this element from analytical systems is that the assets are often more complex and less numerous. They may also require some level of intervention in order to codify them.

For example, capturing project or product development history, experiences or work products often requires some intervention.

Process-based KM

The process-based KM element covers the codification and improvement of processes. Process knowledge assets are often improved through internal ‘lesson’ sessions and internal and external best practice benchmarking.

Developmental KM

Developmental KM applications focus on increasing the competencies or capabilities of an organization's knowledge workers. This is also referred to as investing in human capital18. The applications cover the transfer of explicit knowledge via training or the planned development of tacit knowledge through developmental interventions such as experiential assignments or membership in a community of interest.

Innovation/creation KM

Innovation/creation-based KM applications focus on providing an environment in which knowledge workers, often from different disciplines, can come together in teams to collaborate in the creation of new knowledge. The innovation/creation of new knowledge is the one receiving the greatest attention currently. The focus in this element is on providing an environment in which knowledge workers of various disciplines can come together to create new knowledge.

An alternative method of classification is in terms of knowledge strategies. Hansen et al.19 suggest that businesses followed two mutually exclusive knowledge management models, called codification and personalization.

1 Codification strategy – the approach by which knowledge is carefully extracted from people, codified into documents and stored as knowledge objects or products in databases, from which it can be accessed and used easily by many staff within a given organization. People gain insight from documents.

2 Personalization strategy – this is an approach that focuses on knowledge sharing via person-to-person contact. People gain insight from other people.

For the codification approach, significant IT support is required. For the personalization model, IT is much less important than social interaction. Fundamentally, KM has much wider implications than data management and information management. Many commentators observe that KM is not new. What is new is the phenomenal growth of technologies that make it easier to implement KM systems. Technology is simply a catalyst in the KM movement. As technologies continue to evolve rapidly, especially in the areas of collaboration and search engines, they will enable more sophisticated KM. Notwithstanding its importance; technology is not the biggest challenge in implementing effective KM. Indeed, there is some evidence that there is no direct correlation between IT investments and KM, or business performance20. The bigger challenge is of organizational cultural issues, such as departmentalism, that often divide allegiances and block the transfer of knowledge from individual minds into the organization at large. Another barrier is the poverty of far-sightedness of senior management, who often fail to support knowledge and learning behaviours.

Internal marketing and knowledge management and learning

The metamorphosis of an organization into a knowledge-led organization can be aided by internal marketing. Internal marketing enhances the correct performance of knowledge management.

Internal marketing allows the organization to enhance customer service and customer care. It does this by building internal competencies and understanding of who the customers are and what they want. Knowledge and learning is driven by an appreciation to improve customer outcomes through continually building and upgrading organizational insight. Knowledge and learning are the capacity to pass that learning on from one individual to the next, from one department to the next, and from one generational time period onto the next. It is easy to see that internal marketing can be used as a tool to help knowledge management and learning.

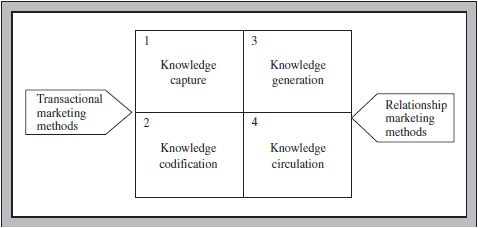

Ballantyne21 links knowledge management and internal marketing by first putting forward two methods of internal marketing:

1 Transactional marketing (aiming to satisfy customers’ needs profitably)

(a) To capture new knowledge.

(b) To codify knowledge.

2 Relationship marketing (aiming to create mutual value with customers or other stakeholders)

(a) To generate new knowledge (through cross-functional project groups, creative approaches, innovation centres, quality improvement teams, etc.).

(b) To circulate knowledge (through team-based learning programmes, skills development workshops, feedback loops, etc.).

In each case, the marketing methods are internally directed. These can be depicted as a matrix of internal marketing activity (see Figure 8.2).

In terms of knowledge management, the role of internal marketing is knowledge renewal and occurs in two main ways:

1 Knowledge generation – the creation or discovery of new knowledge for use within the organization, with external market intelligence as input.

2 Knowledge circulation – the diffusion of knowledge to all that can benefit, through the chain of internal customers to external customers.

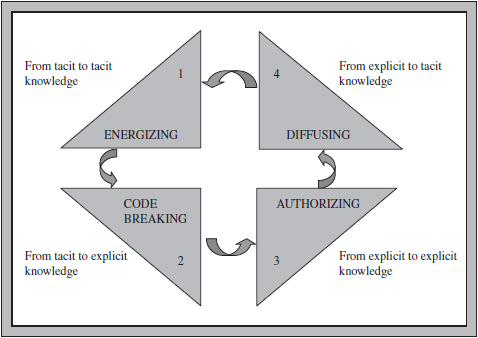

In terms of learning, Ballantyne proposes four distinct modes. These modes are:

Figure 8.2 Internal marketing and knowledge management. Source: Ballantyne, D. (2000). Internal relationship marketing: a strategy for knowledge renewal. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 18 (1), 274–86.

1 Energizing – learning how to work together on useful marketplace goals that are broader than the bounds of any individual job description. What people feel explains a great deal of the what and how and by what means they want to achieve. To energize employees, it is necessary to be able to touch their deeper values and motivations in some way or another. Energizing is the energy of renewal that comes directly from doing an act22.

2 Code breaking – learning how to apply personal resources of ‘knowhow’ in working together to solve customer problems, create new opportunities and change internal procedures. The primary source of knowledge is the individuals themselves. Learning to trust is fundamental. Companies ‘learn’ through their employees. Employee insights are tested by action, in which it becomes possible to observe what works and what doesn't work. To find out whether the insight has wider application, it becomes necessary to test the personal know-how in group settings. Such wider demonstrations also serve to provide confidence to challenge entrenched internal policies and procedures.

3 Authorizing – learning to make choices between options on a costbenefit basis and gaining approvals from the appropriate line authority. To change any particular process or policy it is necessary to get support through a well-documented argument. An understanding of the broader context is helpful in this. This also requires advocacy and listening skills, as well as support of senior management who possess the power to influence.

4 Diffusing – learning how to circulate and share new knowledge across managerial domains in new ways. The diffusion of ‘new’ knowledge is more than one-way communication. It requires dialogue. ‘Can we trust them?’ is the question staff often ask themselves. Trustworthy actions from management are the secret of gaining staff buy-in.

Feedback from each activity helps to adjust the direction of the cycle as a whole and the activities it comprises. This action and feedback pattern acts as a reinforcing circle. Each learning mode is complementary to the whole. Working in this way, the whole becomes more than the sum of the parts.

Generating new organizational knowledge is closely intertwined with dialogue. The process of organizational learning is not the same as having a knowledge repository. Even more importantly, learning does not occur just through the capture and processing of information from the market and adapting to it. It requires actively reshaping the assumptions on which existing knowledge is built. This reconstruction of meaning is central to knowledge renewal.

Mapping the four learning modes onto Nonaka and Takeuchi's23 fourphase theory of knowledge creation, Ballantyne highlights the concept of knowledge renewal (see Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3 Internal marketing as knowledge renewal. Source: Ballantyne, D. (2000). Internal relationship marketing: a strategy for knowledge renewal. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 18 (1), 274–86.

1 Energizing – developing common knowledge (socialization: knowledge interactions from tacit to tacit). What is at issue at this phase in knowledge renewal is the willingness of employees to pass on to each other their hard won know-how. The processes involved in capturing new knowledge can be quite subliminal. We may be able to do certain things without really understanding what we are doing and how we are doing them. This makes the task of transfer more difficult. This phase is ‘energized’ by the sharing of tacit knowledge, a tacit to tacit process, thus amplifying common knowledge under conditions where trust is present.

2 Code breaking – discovering new knowledge (externalization: knowledge interactions from tacit to explicit). This phase is about moving tacit knowledge to explicit through creative dialogue. Creating staff overlaps between departments helps to create a climate for knowledge discovery. This underpins frequent and higher quality interaction between departments. In ‘overlapping’ work situations, managers and other employees are challenged to reexamine what they take for granted. This leads to ‘code breaking’. By using their common knowledge, workers in teams can convert insights generated in dialogue into possible new solutions to customer problems. Teams expand the scope of alternative options and thereby widen the source of new knowledge creation. In a supportive environment, mutual obligation soon develops, which feeds back into the process. This phase is characterized by interaction in the discovery of new knowledge.

3 Authorizing – obtaining cost-benefit knowledge (combination: knowledge interactions from explicit to explicit). The transfer of knowledge in this phase is from explicit to explicit. Two-way dialogue between departments based on trust contributes to readiness to make decisions. Readiness feeds back into further dialogue. Obtaining cost-benefit knowledge is an analytical task familiar to every organization and yet it is a difficult one to make. There are always competing agendas in large organizations and often insufficient knowledge of the impact on current or proposed policies. This phase is characterized by bringing together explicit knowledge on costs and benefits.

4 Diffusing – integrating knowledge (internalization: knowledge interactions from explicit to tacit). The final knowledge transfer is from explicit to tacit. Managing knowledge is not just a matter of processing information. There is a need to circulate, test, integrate and codify new knowledge into new designs, policies, processes and training programmes.

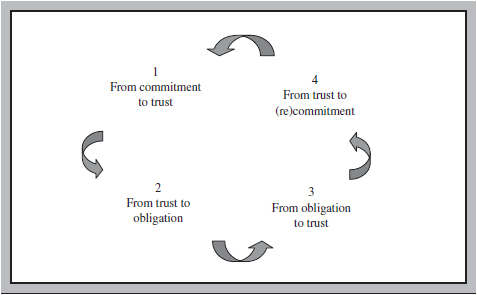

According to Ballantyne, underlying this knowledge renewal process is a cycle that moves from commitment to trust, trust to obligation, obligation to trust, and from trust back to (re) commitment.

Figure 8.4 The cycle of trust and commitment.

Personal commitment is of two types:

1 Commitment to achieve something or to behave in a certain way involves a personal view of the likely beneficial outcomes of internal marketing.

2 Commitment inspired by obligation to others. This involves consideration of reciprocal benefits in order to get things done.

Ballantyne suggests trust is a precondition for obligation but not for personal commitment. Trust means that reliance was placed on another person (or happening) in relation to an expectation. There was some risk involved, or even faith (as in ‘blind’ trust), and certainly some confidence in others as a consequence of past experience. The strength of internal marketing is its intent, coupled with trusting employees and being trustworthy. The much neglected fact is that organizational knowledge is created through interaction and dialogue. The traditional marketing mindset based on the competitive premise blinkers companies to the fact that collaboration is central to much of, if not most, knowledge creation. It is therefore at the heart of creating competitive advantage. Collaboration means the involvement of multiple participants. Marketing departments may play a leading role but the cycle of activity demands collaboration between many different units. For instance, ‘energizing’ and ‘diffusing’ involve new learning behaviours and thus may require high input from HRM, and ‘code breaking’ and ‘authorizing’ require more support from operational departments. Rather than dominance and dictat, internal marketing works best under conditions of equal partnership, in which the leading role is rotated as each department or actor takes the more active role.

For knowledge and learning management not to become a passing fad, it must really take hold in the minds of practising managers. It has to move out of the realm of an ‘interesting idea’ to become a ‘usable idea’. This means getting managers to recognize that knowledge and learning is something they should and could be doing. The role of internal marketing in this is to help give knowledge and learning personal relevance, i.e. engage managers’ motivations. Internal marketing helps to turn the 'should and could do’ to ‘want to and will do’. If this can be done, then KM becomes a usable idea: notably one whose value is recognized and therefore motivated into realization.

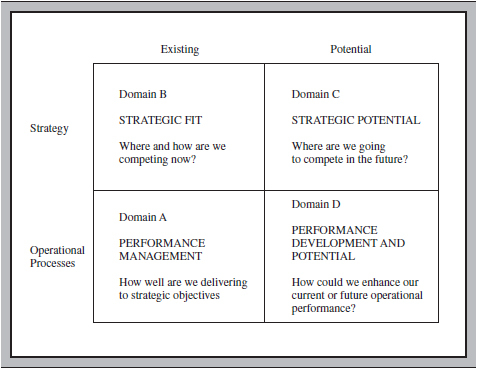

Bailey and Clarke24 are very insightful in developing the notion of personal relevance, which we transpose to the IM context. They suggest that managers can appreciate the relevance of KM by relating the knowledge to be managed into four distinct domains of managerial focus (see Figure 8.5).

Figure 8.5 Managerial knowledge domains. Source: Bailey, C. and Clarke, M. (2001). Managing knowledge for personal and organizational benefit. Journal of Knowledge Management, 5 (1), 58–67.

1 Domain A: The Performance Management Arena – prompts decisions and actions to influence performance.

2 Domain B: The Strategic Fit Arena – prompts decisions and actions about customer management, product portfolio, marketing, competence requirements, etc.

3 Domain C: The Strategic Potential Arena – prompts decisions about investment and development of organization, people, markets, technology and competencies.

4 Domain D: The Performance Development and Potential Arena – prompts decisions and actions to develop products, processes and competencies.

Bailey and Clarke point out that knowledge management is about the generation, communication and exploitation of ideas. Managers can understand the actionability of knowledge management by locating normal managerial activities in terms of generating, communicating and exploiting ideas in one of the four managerial knowledge domains.

Personal relevance is important because:

1 Knowledge starts and finishes with individuals. Knowledge and learning cannot take hold without employees since it occurs through them.

Employees are central agents who surface, share and exploit tacit knowledge. Managing knowledge relies on individual effort and co-operation. Without a high trust environment, individuals place themselves at considerable risk in performing knowledge activities. So unless individuals are able to see the personal relevance (‘what's in it for me?’), then the knowledge and learning initiative will suffer. Internal marketing is a key tool for addressing this challenge. By looking at the employees as customers, it explicitly attempts to examine the cost-benefit for the employee in making the knowledge transaction (sharing, surfacing, etc.).

2 Sharing is not a natural activity.

Examples of this are highlighted in the many failures of knowledge repositories, despite large amounts of investments in technology for sharing. The reason is that companies make assumptions that employees have an innate desire to share information. They could not be further from the truth. Sharing has to be induced through careful management. Even if an employee has a positive attitude toward sharing, the grind of daily pressures works against the time-consuming effort of updating information and sharing knowledge. Consequently, the motivation to share is low.

Put simply, knowledge management and learning will not work if people are unable to see the personal value of KM activities. Without personal motivation, it is unlikely that KM will become integrated sufficiently to create bottom line results.

3 Perceived personal relevance is a precondition for the motivation to think and act differently.

Questions of how to incentivize, reward and recognize knowledge management and learning are preceded by important questions about how the adoption of a KM frame of reference actually benefits the individual. In other words – why should any manager or employee adopt knowledge and learning perspective?

Clearly, knowledge and learning requires managers to think differently about organizational work and KM activities require managers to change how they invest their effort and time.

Personal relevance is critical when people are considering doing something they do not have to do, especially if it incurs considerable personal expense and is not easily recompensed. To gain and sustain commitment to valuing KM, personal relevance needs to tap into something more fundamental than immediate extrinsic gain. For example, why should a senior executive risk investing organizational resource and personal reputation to create favourable conditions for knowledge management? Changing the culture may fail and therefore damage his reputation or the positive effects occur so far into the future so as not to be of any benefit to him. Similarly, why should a line manager invest his already pressured time in knowledge-sharing activities outside of his or her immediate area of operational concern? Something more than extrinsic reward is required to motivate and engage in KM activities. Managers need to see how KM can enhance their personal effectiveness in achieving what they want to do, in a way that would not otherwise be possible relying on their current way of thinking.

By paying specific attention to the issue of real personal relevance, in getting involved in a specific set of activities, it becomes possible to:

1 Bring clarity to where and with whom individuals need to focus their effort in order to gain maximum organizational and individual benefit.

2 Highlight to employees and managers alike what ideas to use to enhance their personal influence in their organizations.

Both these issues are critical for organizations and individuals. Relevance is achieved if people in every role can see how knowledge management and learning enhances their effectiveness.

Employees can increase their personal effectiveness if they are able to focus their expert knowledge in a way that naturally contributes to organizational success. In turn, this enhances the visibility of their personal contribution and enables personal influence to grow. Internal marketing is a highly useful activity in this. If internal marketing can help to bring the right ideas, at the right time to the right people, then it enables effective knowledge management. More than this, if internal marketing can help people see the relevance of why they should engage in knowledge activities it becomes a true enabler of knowledge management. Internal marketing's adoption of a cost-benefits transactional approach for employees tackles the very heart of the notion of personal relevance: what is the gain to the employee for engaging in a specific organizationally directed action and what is the cost of doing so. Internal marketing explicitly attempts to address these two questions.

Understanding role differences

Bailey and Clarke also note that the distribution of organizational responsibilities through managerial roles has a significant impact on the management of organizational knowledge. In most organizations, the responsibility for the domains in Figure 8.5 rests with particular managerial roles. Due to the effects of organizational hierarchy, managerial roles are differentially positioned to generate, communicate and exploit information. They provide access to different realms of ideas, different groups of people and different opportunities for utilizing ideas. For example:

![]() Senior executives – are positioned to take an external focus and possess an internal overview. They have shareholder insight and the organizational power and visibility to influence the communication and exploitation of ideas. Because of this, they are able to generate ideas about future direction (domain C), communicate this to senior colleagues for implementation and ensure that this information is exploited for organizational gain.

Senior executives – are positioned to take an external focus and possess an internal overview. They have shareholder insight and the organizational power and visibility to influence the communication and exploitation of ideas. Because of this, they are able to generate ideas about future direction (domain C), communicate this to senior colleagues for implementation and ensure that this information is exploited for organizational gain.

![]() Functional managers – are well placed organizationally to understand strategic direction as well as operational performance. They are able to generate information about gaps in current strategic capabilities (domain B) and work with managers to improve performance in these key areas.

Functional managers – are well placed organizationally to understand strategic direction as well as operational performance. They are able to generate information about gaps in current strategic capabilities (domain B) and work with managers to improve performance in these key areas.

![]() Front-line managers – are well placed organizationally to understand strategically relevant performance requirements as well as operational issues. They know about current performance levels (domain A) and work to improve alignment and productivity.

Front-line managers – are well placed organizationally to understand strategically relevant performance requirements as well as operational issues. They know about current performance levels (domain A) and work to improve alignment and productivity.

![]() Technical specialists – are well placed to understand technical problems and possibilities, such as know-how to enhance products, services or competencies (domain D) and work with managers to exploit these ideas.

Technical specialists – are well placed to understand technical problems and possibilities, such as know-how to enhance products, services or competencies (domain D) and work with managers to exploit these ideas.

Explicitly recognizing that each manager has unique access to generate, communicate or exploit is an important condition of effectiveness. However, faced with multiple tasks, competing agendas, pressures of time, change and ambiguity, it is all too easy for managers to become disconnected from how they can really add value. Under these conditions, managers easily lose sight of their unique focus. They begin to under-utilize or, worse still, undermine others’ contributions. As Bailey and Clarke state: ‘Senior executives can find themselves in domain B, ‘‘Shooting from the hip’’ – generating short-term reactive strategic shifts, without apparent relation to future strategy or current capability. Functional managers can find themselves ‘‘hands on’’, ‘‘lost in operational detail’’ in domain A, ‘'seizing the reins’’ – taking control. Meanwhile, front-line managers, ‘‘head down’’ in domain A, just get on with the job – turning the handle – and technical specialists resort to producing quick fixes expensively or ‘‘divorced from reality’’, ‘‘indulging in ivory tower thinking’’ in domain D. And as for domain C – strategic potential – it appears that there's no one there!’

If a company is to become a high performer, then it must focus managers on their unique role and learn how to leverage it for organizational benefit. This comes from the ability to direct the right ideas to or from the right people in the right way from one knowledge domain to another. This is the hallmark of effective, influential and organizationally valuable individuals. Appropriate change comes about when the right knowledge is made available, shared and used to organizational advantage. In other words, to be effective, managers need to keep a focus on their own role but be active in other knowledge domains by communicating relevant information within and across domains.

Effectiveness is about the successful flow of ideas. It hinges on where individuals get ideas from, to whom they communicate them to, and how successful they are in getting them exploited when they are not in a position themselves to get ideas directly or to exploit them. This is the fundamental issue of managerial influence – how to get someone to act on an idea they would not otherwise do.

To illustrate this notion of greater personal effectiveness, each of the roles is elaborated next.

Front-line managers

Performance management (domain A) is the essential focus for front-line managers. Front-line managers’ focus of knowledge is about the operations that enable the delivery of strategic goals. Their prime activity is to establish, monitor and manage the operational processes using that knowledge. However, to add value they need to look beyond this domain. They need to seek and communicate ideas gained through their work activity to others who can exploit them in other domains. It is this activity which leverages tacit knowledge and potentially creates value, and enables effective change. Success in this provides the individual with personal credibility, influence and visibility.

What this highlights is that for front-line managers to be organizationally effective and enhance their personal status they need to:

![]() Understand and work with the bigger organizational picture.

Understand and work with the bigger organizational picture.

![]() Have a view about wider business issues, to enable them to better position their ideas about performance, competence and technical issues in context.

Have a view about wider business issues, to enable them to better position their ideas about performance, competence and technical issues in context.

![]() Know who in their organization has a managerial interest in the different domains.

Know who in their organization has a managerial interest in the different domains.

![]() Understand what is actionable by people in these other roles.

Understand what is actionable by people in these other roles.

![]() Think and act outside the box so as to influence others who can take action around issues of significant organizational currency.

Think and act outside the box so as to influence others who can take action around issues of significant organizational currency.

The personal motivation for front-line managers to adopt a KM perspective lies in understanding exactly how, by generating, communicating and exploiting information from within domain A, they can increase their visibility and credibility. The use of internal marketing can help in all of these areas.

Senior functional or operational managers

Senior and operational managers’ role is to co-ordinate and implement strategy through the expertise and activities of their own specialist disciplines. They have access to information about functional requirements, performance expectations, resource, and technical capability and potential. Their activities focus on using that information to ensure continuing strategic fit (domain B). To add value, these managers need to combine their knowledge with that of other managers in domain B. In this way, they facilitate co-ordinated business effort. These managers need to use their knowledge to align operations with strategy and be informed of any newly emerging trends or organizational competencies. They also need to know about how and where to invest in development activities (technical, product, people) to create the greatest organizational benefit.

Managers in these roles need to work with peers across the organization on the issues in domain B to:

![]() Generate and share ideas about how well the organization is performing against current strategic aspirations.

Generate and share ideas about how well the organization is performing against current strategic aspirations.

![]() Understand new strategy requirements against the company's internal competency profile.

Understand new strategy requirements against the company's internal competency profile.

![]() Exploit ideas through agreed changes to maintain strategic fit.

Exploit ideas through agreed changes to maintain strategic fit.

Managers in these senior roles are often trapped in functional mindsets. They narrowly optimize operational performance, forgetting how the pieces of functional expertise come together to create overall performance. This leads to optimizing parts but sub-optimizing the whole. Unfortunately, it is common for managers in these roles to find themselves dragged down into the minute details of their own operational responsibility. Often, they end up focusing on areas of past success and strength rather than rejuvenating and building for the future. The net result: they put all their energies in a narrow area of knowledge leverage, ignoring other alternatives which in the long run may hold higher potential and impact. In this way, they seriously under-leverage the potential of knowledge.

To be more influential, these managers need to be able to think and act more from a general management viewpoint, not just their own specialist perspective. They need to:

![]() Know which managerial knowledge is critical to future strategic direction and operational performance.

Know which managerial knowledge is critical to future strategic direction and operational performance.

![]() Appreciate what others uniquely bring to the table.

Appreciate what others uniquely bring to the table.

![]() Be clear about what and how they really add value to their organization, so that their contribution to the strategic fit arena can be properly put in context.

Be clear about what and how they really add value to their organization, so that their contribution to the strategic fit arena can be properly put in context.

![]() Be critical about how their own specialism makes a difference to others.

Be critical about how their own specialism makes a difference to others.

The motivation for managers in these roles to adopt a knowledge and learning perspective is to be able to understand and use the real added value of their specialism, overcome frustrations in getting co-operation from their peers and be able to extend their sphere of influence in getting things done.

Senior executives

Top management ask and address the question of ‘Where are we going to compete in the future?’ (domain C). They are positioned to develop and exploit strategic ideas and to set conditions for the flow of knowledge around the business to ensure that managerial decisions are taken effectively to address continual change requirements. To add value, they need to leverage external knowledge that others are not party to, make informed judgements about trends in the uncertain future so that they can create clarity of direction. They then need to communicate well and widely that which is fundamental and critical to organizational success.

All too easily, senior executives become stuck in current strategic, or even operational, issues in domain B and lose sight of the need to generate the questions about domain C issues. Senior executives have to step up from managing to leading. They must use their organizational visibility to convey what is strategically important. They must focus their activities to create knowledge cultures that value creating, sharing and leveraging knowledge. Their value-adding activity is to develop a clear vision of strategic potential. This requires a deep grasp of the external business and industry environment to spot opportunities. Visions in themselves are insufficient. Senior executives must devote time to communicate them in ways that are relevant to those around the organization who are best placed to implement them.

Senior executives’ motivation to adopt a KM perspective lies in being able to:

![]() Understand where to focus their time to maximize organizational impact.

Understand where to focus their time to maximize organizational impact.

![]() Know where and how to promote better utilization of other managerial resources.

Know where and how to promote better utilization of other managerial resources.

![]() Know what to focus on in communicating to people throughout the organization so as to influence culture and performance.

Know what to focus on in communicating to people throughout the organization so as to influence culture and performance.

Technical specialists

The task of enhancing operational performance (domain D) is the primary focus of ‘technical’ specialists (e.g. R&D experts, IT specialists). Typically, these roles bring specialist knowledge to bear upon the processes, products and challenges of the company.

The major knowledge management challenge for this group is how they can really leverage their specialist know-how for organizational advantage and not become ivory tower thinkers disconnected from the real world of business. The emphasis for this group is to be able to communicate and exploit ideas with the rest of the business, particularly with front-line managers in domain A and senior executives in domain C. There is the need to translate specialist knowledge in managerially relevant terms. This means getting beyond technical jargon and overcoming the tendency to communicate technicalities at the expense of explaining how something works in a language others can comprehend.

Overall, internal marketing's role is to help the process of establishing personal relevance. Internal marketing can do this by:

1 Establishing status (of current engagement).

2 Establishing focus and energy. Where are people spending their energy and time?

3 Establishing effectiveness. How well are people performing in these knowledge tasks/domain areas?

4 Establishing conduciveness. How good is the company in creating the conditions for employees to create and share knowledge in and across domains?

5 Establishing improvement areas. What are the improvement areas and how can improvements be made?

6 Establishing actions. What can be done to improve their influence and benefits?

7 Establishing accountability. Who needs to do what and when?

8 Establishing communication. How effective is the company at helping the individual to generate, communicate and exploit ideas for organizational benefit? What could increase this effectiveness?

9 Establishing individual cost-benefits. In what ways are people benefiting in carrying out knowledge activities?

10 Establishing relevance. Are knowledge activities relevant to them? Do they enhance their influence, position, etc.?

11 Establishing leverage. What knowledge should the company be seeking to leverage? With whom? What are the benefits of this to those involved?

12 Establishing organizational cost-benefit. In what way and to what extent does the organization benefit from these activities?

Internal marketing can be used to conduct an internal audit to define the personal relevance, current status and actionability of engaging in knowledge activities. Internal marketing can also be used to tackle a host of other interpersonal and organizational factors, especially the issues of power and politics. Managers, when they begin to generate, communicate and exploit knowledge in their own and across domains, inevitably begin to challenge the status quo. This sets in motion changes that start to alter power balances. Often, such shifts lead to power and political strife. Not only does internal marketing play a role in communicating change and channelling relevant information, the way the communication is managed influences the social and political context. Internal marketing, if used properly, can also be used to understand and manage the socio-political context.

Internal marketing communications for knowledge management and learning

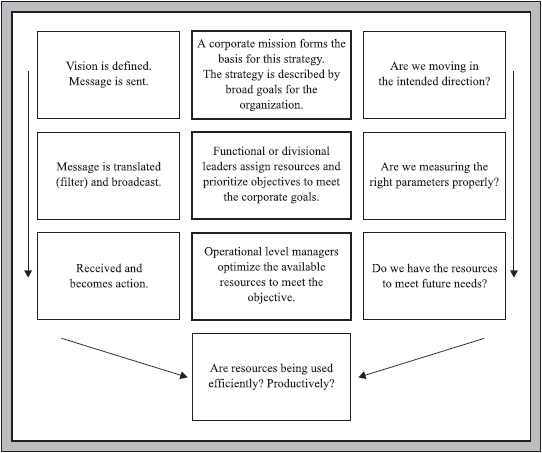

Communication is a critical factor to the successful implementation of any change in an organization. This is even more critical for a knowledge and learning organization. What is often missing in workplace communications is the listening aspect. Listening is critical in understanding what the other person heard and perceived. This is especially critical when a message (e.g. strategy) is passed through many layers of the organization. Each layer filters the information through its own bias before passing it on to the next. Appelbaum and Gallagher25 propose a model of how the communication loop needs to be closed for an organization to progress in the intended direction (see Figure 8.6).

As we noted earlier, knowledge management and learning organization is very much about dialogue. The flow of ideas throughout the organization plays an important role in knowledge creation. Communication is not just verbal. A company communicates not just through explicit messages, but also by its measurement system, its reward system and through its structure. This includes actions such as training and development and any other artefact that is created. Particularly powerful is the communication that occurs through the articulation of objectives. The power of objectives is often underestimated. Once decisions concerning objectives are cascaded into the company, they can have a profound impact. Once defined by a list of objectives and a set of measurements and rewards, an organization will perceive that everything not on the list is unimportant.

Figure 8.6 Closing the communications loop. Source: Appelbaum, S. H. and Gallagher, J. (2000). The competitive advantage of learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 12 (2), 40–56.

Measurement and communication

Vision and strategies of a company dictate what needs to be measured. Measurement must be linked to goals and cannot be mutually exclusive.

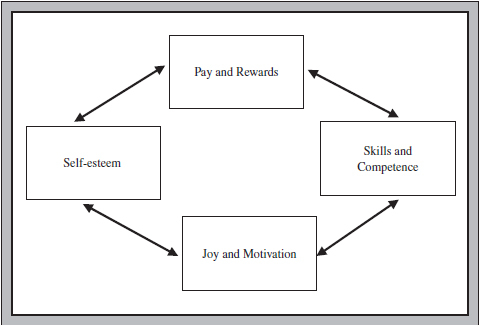

Once a company has devised its plans, the next step is to communicate it to its employees. Measuring non-financial indicators is an important step in communicating (what is important), training (what to look at, what to train for) and organizational development (how performance in one area impacts upon the group). Selecting the appropriate measurement metrics is critical. Kaplan and Norton26 suggest the use of a balance of performance drivers and outcome measures to determine if an organization is making progress toward its goals. The balanced scorecard, by incorporating a broad set of measures, adopts a holistic view of an organization. As Kaplan and Norton note: ‘flying an airplane with the altimeter is fine, until you run out of fuel’. This contrast holds well for companies whose sole preoccupation is the monthly bottom line. If measurement is narrow then it drives a very narrow set of behaviours. The risk in this approach is one of gaining in a single area but sub-optimizing the totality, especially so if the company ignores critical variables27. Vision and strategies of a company dictate what needs to get measured and the measurement must be linked to goals, and the two cannot be mutually exclusive. To measure an employee it is necessary, likewise, to take a holistic view. One way of doing this is to construct an employee balanced scorecard (see Figure 8.7). An employee scorecard should be constructed not simply to reflect efficiency and productivity (as is typically reflected in rewards and pay), but also include less tangible factors, such as how does the job enhance a person's skills and competence, how does it bring joy and motivation, and how does it enhance the self-esteem of the individual. Taking an encompassing view of the employee and his job allows for a more balanced assessment of what to do and how to move an individual toward customer consciousness.

A knowledge and learning organization must have an appropriate measurement system. Without measurement systems and tools, it is difficult to move from theory to reality because there is no reliable feedback to build improvements upon. Measurements assess the current, in order to determine which actions must be taken to manage the progression towards a learning organization28. Metrics must be:

1 Meaningful.

2 Manageable.

3 Measurable.

Each of the three Ms indicates why it is so difficult to find examples of learning organizations.

Knowledge management is concerned with which knowledge should be available where, when and in what form within an organization. Internal marketing is concerned with assembling, synthesizing and packaging knowledge to enable effective transfer and action. Internal marketing is therefore a fundamental enabler of KM. Internal marketing attempts to improve the processes and systems used to transfer and manage knowledge, and does it as an ongoing, continuous critical function. Internal marketing in this respect works like a proposal to its employees, to engender specific types of actions and behaviours. Proposals are, first and foremost, ‘products’ that include a host of information and education. Through a choreographed process of generation, transfer and congealment, the internal marketing proposal is designed to sell both the benefits derived from implementing desired actions from the employee, and also training and tools to accomplish all required activities. In addition, the proposal must convey not just tangibles but speak to the intangible values of the individual.

Figure 8.7 Employee balanced scorecard.

One of the most important aspects of internal marketing is communication with employees. Internal communication lets employees know what is going on so that they can do their jobs effectively and efficiently. This is the basis for serving external customers and internal customers well. Internal cues and communications signal to employees which activities are acceptable and which are not. Pronouncements issued from senior management in company reports are not very good at dispersing and internalizing strategic knowledge throughout the company. Getting people to share their knowledge requires new processes but, more importantly, it requires setting a new covenant between employer and employees. Workers have to be reassured that they will still be valued after they give up their know-how. In short, it involves treating the employees as partners in the firms.

Leadership and internal marketing communication

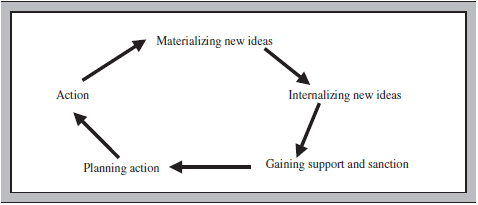

Top management play a visible role. Senior managers act as knowledge and learning champions. Their actions are very important cues in supporting implementation. What they do and how they facilitate programmes lends support to the idea of knowledge management. Their actions can help to overcome resistance, help the sharing of ideas and enhance involvement in activities that promote learning. They can trigger a positive learning cycle, which embeds new concepts and ideas via a process of materialization and internalization. Subsequently, action is created.

Figure 8.8 illustrates the example of the promotion of learning through materialization, internalization, support and commitment, and practical activity. In the case of a positive cycle, ideas are actively transformed into action in the implantation of knowledge management thinking. Learning functions as a mechanism by which new ideas and thinking are implanted. Applied to the process of organizational implementation, learning occurs through the stages of materializing ideas, internalizing ideas and concepts, gaining support to the idea, preparing a plan of action and, finally, activity. This cycle of four stages represents an ideal framework for a cyclical learning process. Through participation in continuous organization-wide training, people learn the idea of knowledge management and resistance is gradually overcome. In the course of the process, people also learn new working methods. Mental integration of organization members increases involvement and supports implementation.

Figure 8.8 The positive implementation cycle.

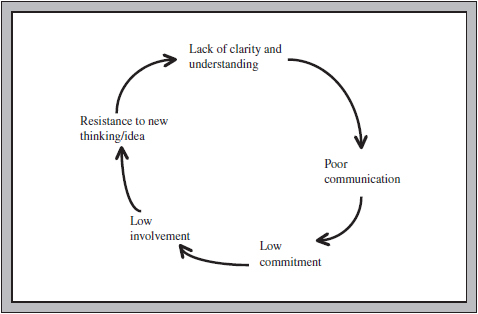

Figure 8.9 shows a negative cycle of implementation. This leads the organization to avoid effective learning. When managerial perceptions are unclear, employee commitment is adversely affected. Vagueness and low commitment have an unfavourable effect on the progress of the KM programme. Ideas are not shared and sufficient support to the knowledge and learning effort is not gained. As a consequence, the effort falters and ends up failing to prosper across the organization.

Figure 8.9 The negative implementation cycle.

Nucor's Chairman's Kenneth Iverson notes in reference to the company's learning efforts: ‘We've tried a lot of technologies, and our success is probably 30 per cent the result of new technology – and 70 per cent due to our people’29. Clearly, employees are the primary factor driving the success of his firm. This is an important aspect of the knowledge economy: as companies invest in technology they overlook the fact that the payback is dictated by people using equipment and systems, not the machines themselves. Indeed, as Sheridan30 goes on to suggest, there are two fundamental ingredients: I think you need a good strategy, but you also need to do the dailies well. Building an effective global company is 10 per cent strategy and 90 per cent implementation of the daily requirements.

The implications of this for organizational learning are:

1 Companies making decisions based only on financials will not fully utilize all of the assets that they have at their disposal.

2 Investment in technology, although important, is not the final answer. Developing a company that captures the ideas and knowledge of the people that engineer the system brings a greater return.

Knowledge management implementation is an incremental process. It needs to start by the development of a common language for knowledge management. This occurs through materialization of ideas. Adopting and internalizing knowledge management thinking is a major challenge of learning. If this is not tackled adequately, unclear perceptions will develop and lead to a weak common foundation. This results in insufficient support for the knowledge initiative, which weakens commitment to it. Low commitment generates resistance to the adoption. This is a challenge for top management, in particular. In order to avoid transient knowledge management efforts, top management must internalize and communicate the values and vision to create a common language and increase commitment. This is one of management's most significant tasks in creating a knowledge management culture. Promotion of concepts, values and principles cannot be overstated.

Language is a very important aspect of communication. And ‘languaging’ is the art of word choice31. To ensure that knowledge is understood and shared effectively and efficiently, companies must develop and implement an enterprise-wide vocabulary. Great care is needed in defining or redefining the images employees hold and the language the organization uses. Language exerts a profound influence on perceptions of ourselves, our companies, products and indeed our entire world view. Consequently, language impacts the way we manage and the way we behave.

In this role, it is important to remember to use metaphors and transformed iconography (or ‘word pictures’), because they expand the domain of possible and realizable interactions and approaches. They are rich transporters of information. ‘Metaphors allow the transfer of bands of information where other means only transfer smaller bits’32. New metaphors and words create not just new linguistic domains, but enable capture and promotion of new concepts, thoughts, discourse and behaviours. Used properly, these can help guide business actions. They offer senior managers a multidimensional mode of understanding and transfer mechanisms.

The implications of communication for organizational learning are:

![]() Communication, sending and receiving, ties pieces of the learning jigsaw together.

Communication, sending and receiving, ties pieces of the learning jigsaw together.

![]() Managers need to realize that they are communicating in everything that they say and do, and they communicate most clearly when the two align.

Managers need to realize that they are communicating in everything that they say and do, and they communicate most clearly when the two align.

![]() There are filters everywhere; just because your message was clear in your mind does not mean that it is clear for everyone to whom it may have been intended.

There are filters everywhere; just because your message was clear in your mind does not mean that it is clear for everyone to whom it may have been intended.

Undoubtedly, the most common internal marketing application is in the crafting of internal communication strategies. When this is done in parallel with external marketing communications, advertised promises stand a better chance of being fulfilled to the required level of performance, because staff are better prepared to perform them.

A story that has become part of IBM folklore describes how a young engineer who was responsible for a very risky project that cost $10 million went to Thomas Watson, president of IBM, after it was found that the project could not be implemented. ‘I guess you want my resignation,’ said the engineer to Watson. Watson replied: ‘You can't be serious. We just spent 10 million dollars educating you.’ Watson's behaviour influenced the IBM members’ willingness to take risks, especially in the area of new ideas and development.

Leaders influence organizational values relevant to the functioning of the organization. Even more, just as leaders influence values, they also influence the forms of thinking, the level of motivation and the behaviours relevant to organizational learning. They exert this influence through several channels. Jan Carlzon33, CEO of Scandinavian Airlines (SAS), coined the phrase ‘moments of truth’ to refer to those critical episodes of behaviour that transmit clear messages about ‘what is important here’, ‘how to behave’, ‘who is important’, ‘ who is a role model in the company’ and so forth. These actions become behavioural co-ordinates for others in the organization. Popper and Lipshitz34 highlight three channels of leadership influence:

1 Time devoted by the manager. There is a saying that ‘the urgent tends to take precedence over the important’. The daily tasks, the need to meet short-term schedules, often take precedence over dealing with important long-term issues. Allocating ‘manager time’ is thus a clear signal to the staff as to what is more important and what is not. The fact that managers who are extremely busy with urgent tasks invest ‘manager time’ (which is a very expensive resource) in some actions and not in others influences employees’ order of priorities. The fact of allocating precious ‘manager time’ to an issue conveys an unmistakable message concerning the importance of that value.

2 Managers’ attention. Managers’ attention has an effect similar to the investment of ‘manager time’. Managers who consistently pay attention to certain subjects send a clear message about its importance. For instance, a manager of a company wishing to convey the message that client satisfaction was more important than profits didn't let a day pass without asking every local manager what the clients said about them and their service. This consistent interest conveyed a message that eventually became internalized.

3 Reward and recognition. Channels of reward and recognition are the most common means of influence in organizations. They establish criteria regarding the desired behaviours. These channels include various bonuses, letters of appreciation, promotion, attractive assignments, allocation of resources, and punishment.

Managers who value and reward learning activities reward people who contribute to organizational learning. They use aspects of learning as part of the process of evaluating employees, and make learning activity a criterion for promotion. By doing so, they reinforce the behaviours required for knowledge creation and learning. On the other hand, punishment for mistakes and impatience reduces the likelihood of sharing and transfer. Even worse, they can totally stop the behaviours of sharing, dialogue and communication that are so essential for learning and knowledge management.

The channels of influence described above affect people's actual willingness to put organizational learning on the organizational agenda. However, even if learning becomes part of the agenda, that in itself is not enough. To manage knowledge and learning the company must root it deeply in the culture of the organization.

The main problem in creating and maintaining learning organizations lies in the tendency of people to safeguard their ‘positive image’ (this is why most people tend to report successes and try to avoid reporting failures and mistakes, even though there might be important lessons to be learnt from failures)35. One major challenge in building learning organizations is to reduce the impact of ‘defensive routines’. Since ‘defensive routines’ are the natural tendencies of people, there is a need to create psychological conditions that change these tendencies and encourage people to be more accountable, more willing to be transparent, more facts (or issue) oriented: in short, less defensive. In this sense, leadership's actions are highly influential because they have high impact in creating an atmosphere that affects learning processes in organizations. The aspects of leadership that generate values conducive to learning are36:

![]() Transparency (i.e. relating to facts without defensive routines).

Transparency (i.e. relating to facts without defensive routines).

![]() Issue orientation (focusing on performance).

Issue orientation (focusing on performance).

![]() Accountability (freedom from the tendency to avoid personal responsibility).

Accountability (freedom from the tendency to avoid personal responsibility).

Indeed, ‘eliminate fear from the organization’ was one of the principles formulated by Deming for introducing TQM to organizations. This principle came from an understanding that ‘improvement teams’ become mere ritual if those involved in them do not feel the psychological safety that allows them to bring up facts and discuss them openly even if the facts were unpleasant. Psychological safety is a state in which people feel safe to candidly discuss their mistakes: what they think and how they feel37. Behaving in new ways and doing things differently can involve some degree of unlearning. This can be emotionally difficult, and often raises anxiety due to feelings of incompetence38. People act transparently and investigate their own mistakes with integrity when they are psychologically safe rather than under threat. Leaders facilitate organizational learning if they are able to inspire trust: trust in their leadership and trust in the processes and system, and specifically, trust in the ‘rules of the game’ maintained in the organization.

The importance of trust to organizational learning has been demonstrated in some studies39. Establishing ‘conditions of trust’ is no less than establishing ‘psychological conditions for effective organizational learning’. Gambetta40 suggests that building of trust requires:

![]() Consistency.

Consistency.

![]() Keeping promises.

Keeping promises.

![]() Discretion.

Discretion.

![]() Morality.

Morality.

![]() Fairness.

Fairness.

![]() Openness.

Openness.

![]() Accessibility.

Accessibility.

Corporate leaders who are able to inspire trust possess four key characteristics41:

1 Idealized influence. Words reinforced by behaviours form a collective and social orientation. Leaders influence by role modelling their behaviour to match their words.

Example: CEO Ralph Larsen of Johnson & Johnson explained his readiness to lose $240 million in earnings in the Tylenol case because ‘if we keep trying to do what is right, at the end of the day we believe the market will reward us’. Senior executives of the company consistently devote considerable time and energy to maintain in practice the 50-year-old credo created by Robert Wood Johnson, son of the founder. The credo emphasizes honesty, integrity and respect for people.

2 Inspirational motivation. Leaders motivate and inspire by creating impelling visions of the organization's future in which the organization is seen to prosper. These leaders praise acts done for the common good, express optimism about the future of the organization, show enthusiasm for shared success and radiate confidence that the aims will be achieved. They exhibit clarity and commitment in thought and action.

3 Intellectual stimulation. Leaders can provide intellectual stimulation by exhibiting a willingness to constantly examine the status quo and not to see the existing situation as an immutable fact. Leaders who can stimulate their employees intellectually help their people to look at old problems in new ways, encouraging them to ‘think differently’. They legitimize creativity and innovation.

4 Individualized consideration. Leaders who are high in personalized attention are able to inspire and motivate their employees. They achieve this by treating each employee as an individual with needs, abilities and aspirations different from those of others. They help strengthen their workers’ capabilities and overcome their weaknesses through training and guidance. They don't punish mistakes but show a willingness to see mistakes as opportunities for learning. When mistakes are made, they are more concerned about asking what happened than finding out who is to blame. Success is not taken for granted but studied as part of the developmental approach.

These leadership behaviours contribute enormously to the formation of values and atmosphere that is conducive to knowledge management and learning. Such leaders are transformational leaders because they inspire high levels of trust. They are able to elicit a more idealistic and ethical level of thinking. They generate more collaboration and sharing, more openness and honesty, more credibility, more willingness to take responsibility, and higher quality performance.

Exhibit 8.1. Virgin: values and leadership as symbols for employee behaviour and action

As companies struggle to find something that gives them a competitive edge, it is no longer sufficient to energize employees through publication of bland corporate newsletters or hold annual outings. Companies have to try to use insights and strategies that they have deployed for acquiring and holding on to external customers on their employees as well. This has led many to turn their attention to internal marketing, which while it might possess the appeal and glamour of above-the-line advertising, is increasingly being perceived as a highly effective means of delivering to customer expectations.

It is a fact that in many corporations employees feel undervalued, uninvolved and lack confidence in their organizations’ leaders and vision. This sums up the challenge for internal marketing programmes. In these circumstances, as Anne Gilbert, director at the Marketing & Communications Agency (MCA), highlights: ‘Asking people to be brand ambassadors is almost like getting them to be internal customers. It means thinking like a marketer. Instead of having fizzy drinks or crisps as the product, the product is the organization, and its goals and its people are the target market. So, just as with external marketing, you have to know what makes them tick, and what motivates them. Why would they buy the goals and objectives?’

Alison Copus, general manager of marketing at Virgin Atlantic Airways, notes that this involves a lot more than coming up with mere mission and vision statements: ‘What counts are your values, and planting those values into employees’ hearts and minds: I think values are more powerful than rules or mission statements because of two things. First, whether they are employees or customers, they give you something with which to identify. And that identification is a very, very strong bond... Second, if you have one shared set of values – shared between your customers and employees – you have a sporting chance of saying what you mean and meaning what you say at every point of contact.’

Copus considers the little things to often be the most important. For instance, the last thing she would wish to lose from her marketing budget is the annual party, to which all employees and their partners and children are invited.

Virgin has a big advantage when it comes to instilling common shared identity and brand values: Richard Branson, who epitomizes and embodies these values. Branson's personal actions and behaviour in relating to employees is crucial in setting the tone of Virgin's employee-focused culture. In Virgin's case, successfully getting its employees to buy into the values of Virgin and its leader is at the heart of its success and truly defines the way it operates.

Source: Mazur, L. (1999). Unleashing employees’ true value: employees can be your company's most valuable marketing asset. Marketing, April, 22–4.

Leaders promote knowledge and learning in three key ways:

1 Putting learning on the agenda as a central issue. This they do through their ability to influence key channels (namely ‘manager's time’, ‘manager's attention’, and the organization's reward and recognition aspects).

2 Building the structural foundations needed to turn individual learning into organizational learning (processes and systems for enhanced sharing).

3 Creating cultural and psychological conditions that facilitate learning (i.e. establishing ‘conditions of trust’).

A simple template for initiating a knowledge management and learning programme is given below as a set of steps.

![]() Step 1. Organizing for KM must start off with education and training for top and upper level managers. This prepares the ground for the sharing of knowledge thinking and getting the entire organization involved.

Step 1. Organizing for KM must start off with education and training for top and upper level managers. This prepares the ground for the sharing of knowledge thinking and getting the entire organization involved.

![]() Step 2. Mapping the company's intellectual capital and competencies against strategic demands made by the external environment.

Step 2. Mapping the company's intellectual capital and competencies against strategic demands made by the external environment.