2

What Is Holistic Improvement?

“Only the over-all review of the entire business as an economic system can give real knowledge.”

—Drucker

Chapter 1, “A New Improvement Paradigm Is Needed,” reviewed the numerous changes that have occurred in the world since the first edition of this book was published (Snee and Hoerl, 2003). These changes have occurred in all aspects of society, as well as the business world. We concluded in that chapter that a new paradigm for improvement was needed. Lean Six Sigma is no longer adequate for the improvements that organizations need to survive and, better yet, prosper. We call this new paradigm holistic improvement. This chapter sets out to accomplish the following:

![]() Define holistic improvement

Define holistic improvement

![]() Show how holistic improvement is different from and more effective than previous approaches

Show how holistic improvement is different from and more effective than previous approaches

![]() Provide a strategic structure for the use of holistic improvement

Provide a strategic structure for the use of holistic improvement

It all begins with selecting the right projects. Next, we need to select the right methods for the specific project, not rely on one method for all problems. Project selection (and, to some degree, method selection) is the Achilles’ heel of any improvement approach. We look at holistic approaches to project identification and selection, as well as method selection, in this chapter.

The Ultimate Objective: Comprehensive Improvement

The warning is wearyingly familiar, but it bears repeating: The leveling effects of globalization and information technology have enabled organizations and individuals around the world to compete successfully. All organizations need to improve continuously or face extinction. Improvement must come on all fronts—quality, cost, delivery, customer satisfaction, risk management, and more. It is in this brutally unforgiving context that attempts to integrate Lean and Six Sigma are taking place. If they are to succeed, and expand to Lean Six Sigma 2.0, they must first define the problem in terms of the ultimate objective. That objective is not to integrate Lean and Six Sigma, or perhaps other methods, but rather to improve performance as comprehensively and sustainably as possible.

Based on our more than 60 years of collective experience with improvement methodologies and improvement programs with leading companies, we believe that organizations that successfully pursue Lean Six Sigma 2.0 will do so by adopting these approaches:

![]() Taking a holistic view of the business and of business improvement

Taking a holistic view of the business and of business improvement

![]() Adopting a common improvement system

Adopting a common improvement system

![]() Establishing an integrated project management system

Establishing an integrated project management system

Guided by those three simple but powerful principles, ambitious organizations can begin to achieve the full potential of Lean Six Sigma 2.0.

A Holistic View of Improving the Business

Reducing waste and cycle time is necessary but not sufficient. Reducing variation alone will not make you a winner. A holistic approach to improvement is needed, with a broader view of how to improve business performance and a deeper understanding of the various approaches to improvement.

The characteristics of holistic improvement show that a holistic approach is more than just a methodology for conducting improvement projects. The type of culture (business, country, or ethnic), function, leadership, management systems, and other key elements of the business must be taken into account as well. The bulleted list that follows shows the characteristics of holistic improvement:

![]() Works in all areas of the business—all functions, all processes

Works in all areas of the business—all functions, all processes

![]() Works in all cultures, providing a common language and tool set

Works in all cultures, providing a common language and tool set

![]() Can address all measures of performance (quality, cost, delivery, and customer satisfaction)

Can address all measures of performance (quality, cost, delivery, and customer satisfaction)

![]() Addresses all aspects of process management (process design/redesign, improvement, and control)

Addresses all aspects of process management (process design/redesign, improvement, and control)

![]() Addresses all types of improvement (streamlining, waste and cycle time reduction, quality improvement, and process robustness)

Addresses all types of improvement (streamlining, waste and cycle time reduction, quality improvement, and process robustness)

![]() Includes management systems for improvement, based on Lean Six Sigma (plans, goals, budgets, and management reviews)

Includes management systems for improvement, based on Lean Six Sigma (plans, goals, budgets, and management reviews)

![]() Focuses on developing an improvement culture and uses improvement as a leadership development tool

Focuses on developing an improvement culture and uses improvement as a leadership development tool

No existing approach can perfectly satisfy all these characteristics, but this is the overall goal. Ultimately, a holistic approach helps develop a culture of improvement throughout the organization, including using improvement approaches as a tool for leadership development.

We define holistic improvement as follows:

An improvement system that can successfully create and sustain significant improvements of any type, in any culture, for any business (Snee, 2009).

A discussion of the key words in this definition is helpful in understanding the breadth and depth of the approach.

First, to create and sustain improvement, certain components are needed. These include an infrastructure of management systems and resources, a continuous improvement culture, and leadership development (Snee and Hoerl, 2003). Also important are long-term solutions that stick and methods that actually work and have a track record of creating improvement.

Significant improvements refers to improvements that enhance all measures of organizational performance: quality, cost, delivery, customer satisfaction, risk management, and the bottom line. The improvements must be noteworthy, as breakthrough levels of improvement instead of ones restricted to routine problem solving.

Any type refers to the specific improvement needed, such as any of the process performance measures noted earlier (for example, to speed up the process flow, reduce variation, enhance process design, improve process performance, create better process control, and optimize process output.). This also encompasses design efforts and the improvement of existing processes. It involves addressing political, legal, or people issues, not just technical issues. A holistic improvement methodology is needed to address this broad array of improvement needs.

Improvement is needed is many places, in any culture, including in any function in the business and any region or culture in the world. In our experience, individual functions within an organization often develop their own cultures, leading to silos. In this situation, an organization is split up into multiple suborganizations, each with its own culture. Cooperation is difficult in these cases.

Organizations run many different types of businesses and processes: any business refers to manufacturing, finance, high-tech organizations, and services. Holistic improvement also works in nonprofit organizations such as healthcare, humanitarian, and government organizations. Obviously, the cultures in nonprofits, Wall Street financial firms, hospitals, and manufacturing plants tend to be quite different. Holistic improvement must be effective in each.

The suggested holistic improvement approach incorporates two major elements, producing what we call Lean Six Sigma 2.0:

1. Integration of a wide set of improvement methodologies so that the most appropriate method can be used to attack a given problem. In other words, no single methodology can solve the full breadth of the problems noted; therefore, multiple methodologies must be integrated. The problem should determine the methodology, not vice versa.

2. A deployment system that provides the needed infrastructure is required to create and sustain improvement across the spectrum of the problems. In our experience, the Lean Six Sigma deployment methodology is the most comprehensive and best-developed improvement deployment system. Therefore, we borrow this deployment methodology and apply it to a much broader set of improvement methods than just Lean Six Sigma.

What would such a holistic improvement system look like? To answer this question, we first consider one real-world example that illustrates some (but certainly not all) of the attributes of Lean Six Sigma 2.0.

An Example of Holistic Improvement

In this scenario, we look at the need to improve the manufacturing organization of a biopharmaceutical product (McGurk, 2004). The organization developed a new blockbuster drug and was creating a manufacturing organization to produce the drug. It soon became clear, however, that the manufacturing process would not be able to meet the market demand. An assessment of the entire organization was performed and found that organizational development was needed in addition to process improvement. A holistic approach was required to address this broad range of issues.

Using Lean techniques, batch release cycle times were reduced by 35–55 percent, depending on the product (Snee and Hoerl, 2005), which resulted in faster product release and reduced inventory and manufacturing costs. Six Sigma techniques were used to further process understanding and increase yield by 20 percent. Within the organization, many who had developed the product had an R&D mind-set, and this needed to evolve into a manufacturing mind-set. The company hosted leadership development workshops to accomplish this. Process operator training helped improve process reliability. Overall, the holistic approach delivered a 50 percent increase in capacity, enabling the process to meet market demand.

As this brief example makes clear, Lean Six Sigma cannot sufficiently address today’s business improvement needs, even in its more modern form of Version 1.3 (Snee and Hoerl, 2017). We have reached the point at which too many problems remain unaddressed by Lean Six Sigma 1.3 for us to ignore (Kuhn, 1962). A new paradigm, or way of thinking about improvement is required to make significant progress going forward.

Six Sigma is excellent at what it was designed to do: solve medium-sized “solution unknown” problems. Version 1.3 also incorporates innovation efforts, new product and process design, and Lean concepts and methods. The supportive infrastructure developed for Six Sigma is the best and most complete continuous improvement infrastructure developed to date (Snee and Hoerl, 2003). If this same infrastructure can be applied to a holistic version of Lean Six Sigma that addresses the limitations discussed earlier, the resulting improvement system would be the most complete so far.

Addressing all the limitations previously noted would not be a minor upgrade; instead, it would be a fundamental redesign based on a much broader paradigm. It would be Version 2.0, not simply Version 1.4. What paradigm would be required to develop lean Six Sigma 2.0? The answer is clear: We need a holistic paradigm of improvement. We need a system that is not based on a particular method (whether that is Six Sigma, Lean, Work-Out, or something else); instead, the system must start with the totality of improvement work needed and develop a suite of methods and approaches with which the organization can address all the improvement work identified.

A holistic paradigm reverses the typical way of thinking about improvement. Traditionally, books, articles, and conference presentations on improvement focus on a particular method and promote that method over others, at least for specific types of problems. It’s easy to find books on Six Sigma, Lean or TRIZ, for example.

But few, if any, books focus on general improvement. Within a holistic paradigm, the focus is not on methods, but on the improvement work and the problems to be solved. Only after the problems have been identified and diagnosed are methods discussed. The individual methods can be applied to the specific problems for which they are most appropriate. In other words, holistic improvement is tool agnostic—the tools are hows, not whats. Comprehensive improvement is the fosus of our efforts.

A Strategic Structure for the Holistic Improvement System

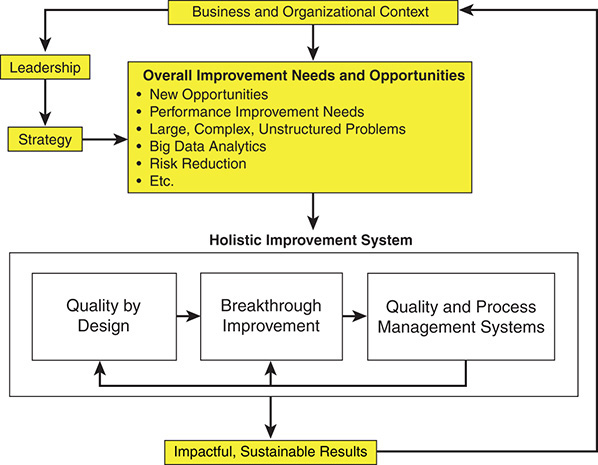

Figure 2.1 shows the high-level framework for a holistic improvement system. All improvement begins with the business and organizational context, which defines overall improvement needs and opportunities. These needs and opportunities also greatly depend on leadership, provided by the organization’s management as defined in the organization’s strategy. Clearly, holistic improvement is a strategic approach.

The holistic improvement system has three critical building blocks:

1. Quality by design, which focuses on innovation and the development of new businesses, products, and processes

2. Breakthrough improvement, which encompasses most of what traditionally is considered to be continuous quality improvement

3. Quality and process management systems, which is the defensive aspect of quality—managing processes with excellence to avoid errors and mistakes, as well as maintaining process control

These building blocks are linked and sequenced, as shown in Figure 2.1. The outputs of the building blocks are impactful and sustainable results, which then enhance the business and organizational context. The cycle continues. Clearly, breakthrough improvement assumes that we have something in place to improve. First, of course, we must identify the market opportunity and design new products and services to meet these opportunities. In addition, as noted in Chapter 1, although design and breakthrough improvements are “sexy” and exciting approaches, these is no substitute for problem prevention. Excellence in quality and process management is still critical to prevent problems and rapidly address routine problems before they become crises.

Figure 2.1 Strategic structure for the holistic improvement system

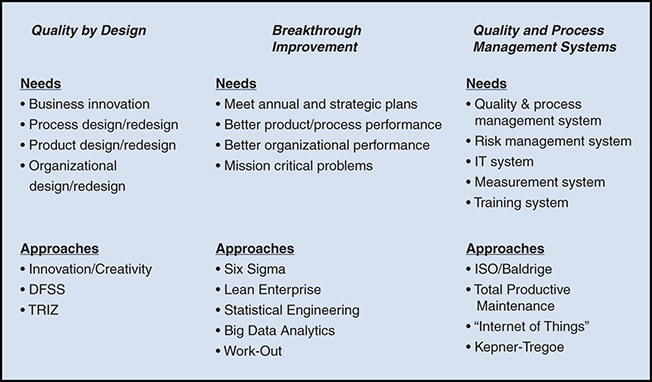

Figure 2.2 shows sample methods and approaches used within the building blocks. Addressing improvement from a holistic perspective puts the focus where it must be: on the problem and the improvement need. The methods are also important but are a secondary consideration. As a result, the impact and bottom-line results of an improvement system are increased and sustained over time.

Figure 2.2 Holistic improvement system needs and sample approaches

Note that each category in Figure 2.2 includes several methods; some or all of these might be needed to address a given issue. Of course, some methods, such as Six Sigma and Lean, incorporate numerous individual tools within their overall approach. In addition, other methods that are not listed in Figure 2.2 might be required. These are simply sample methods that we have seen effectively drive improvement and that we recommend for consideration. We discuss these individual methods further in Chapter 3, “Key Methodologies in a Holistic Improvement System.”

Creating a Common Improvement System: The Case of Lean Six Sigma

The move to holistic improvement is obviously not easy, and requires careful planning, leadership commitment, and time. There are good reasons why jumping from one “bandwagon” to another—based on the latest fads in business journals—is more common than a systematic, long term approach to improvement. We would like to point out, however, that what we propose is certainly not the first attempt at creation of a common improvement system encompassing multiple methodologies. In particular, we would like to consider the case of Lean Six Sigma, which was essentially an integration of Lean Enterprise with Six Sigma. This integration is what we referred to as Lean Six Sigma 1.2 in Chapter 1. We believe this integration provides important lessons that can be applied to the development of a holistic improvement system.

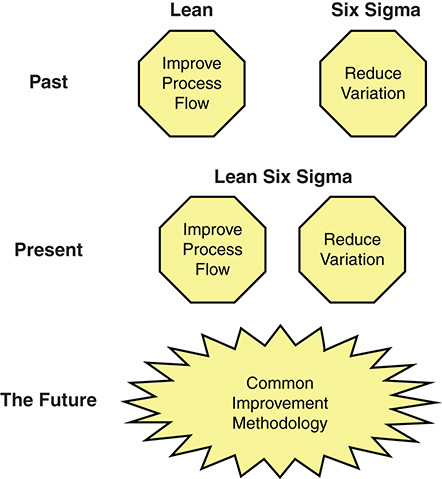

As Figure 2.3 shows, many companies traditionally have focused on Lean or Six Sigma as their overall improvement approach (Snee and Hoerl, 2007). Beginning around the turn of the millennium, some organizations began working to integrate the two under the common name Lean Six Sigma (George, 2002). This integration produced significant results at numerous organizations, including GE, as discussed in Chapter 1. The integration of Lean and Six Sigma provides a positive example, but it does not go far enough for today’s improvement challenges.

Figure 2.3 The evolution of Lean Six Sigma

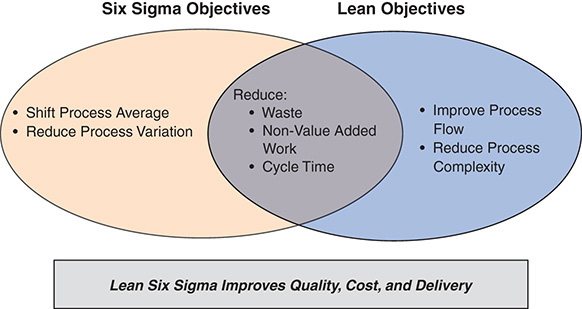

Practitioners have found that Lean principles and tools can be used to deal with issues of waste, cycle time, process flow, and non-value-added work. Six Sigma tools have effectively shifted the process average, reduced the variation around the process average, identified the operating “sweet spot,” and helped create robust products and processes while also reducing waste and cycle time.

A key development in Lean Six Sigma was the creation of a common improvement system. In GE, for example, we witnessed unhealthy competition between Six Sigma proponents and Lean proponents before the two methodologies were integrated into one system. It is a generally accepted policy that the players on a football team should not compete with each other, but should rather cooperate and work together to ensure the success of the team. The same is true within an organization: The competition is the other team, not one’s own teammates! The individual improvement methods are not competitors, but rather diverse tools in a complete toolkit.

To truly integrate Lean and Six Sigma, one infrastructure for deployment was required. That is, the Lean specialists and Six Sigma specialists needed to be in the same organization, with the same leadership direction, funding, goals, and so on. We look at the Lean Six Sigma infrastructure here because we think it is the most complete. For example, the execution of projects in this common improvement system can be guided using the familiar DMAIC approach (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control). DMAIC originated in Six Sigma, but the project management framework of DMAIC can be sharply distinguished from the Six Sigma tools with which it is typically associated and generalized to a higher level as an overall framework for process improvement. Lean projects can be effectively deployed using a DMAIC project framework.

The lesson learned for holistic improvement is that the methods that are the most appropriate to a particular problem (whether Six Sigma, Lean, or something else) can be applied through the highly structured and sequenced approach of DMAIC. A common infrastructure and project framework helps ensure true integration.

As an important aside, we think there is no such thing as Six Sigma tools or Lean tools—after all, neither methodology invented the tools. In actuality, we have only improvement tools; we use the phrases Six Sigma tools and Lean tools simply as a convenience to indicate tools typically associated with each initiative.

An Integrated Project Management System

Creating a common improvement system requires developing an integrated system for managing projects instead of using separate systems for Lean projects, Six Sigma projects, Nike projects, and so on. As Juran admonished, “Improvement happens project-by-project and in no other way” (1989). As noted earlier, improvement begins with selecting the right projects—not the right people, not the right methods, but the right high-priority projects to make the organization successful. The project management system should therefore employ a project-by-project selection and management approach.

In addition, a key element of the project management system is to identify the most appropriate method for each project. As with any effective project management system, processes should guide and sustain improvement: for example, project tracking and review, communications, recognition and reward, and training. In this chapter, we focus on selecting a project and assigning the improvement method. Chapter 7, “Managing the Effort,” covers the other elements of the project management system.

In our experience, project selection is often where the battle is won or lost. When debriefing after unsuccessful projects, it frequently becomes clear that the project was a poor choice from the start. Maybe it had a vague objective, was disconnected from management objectives, or could not significantly impact the problem due to issues beyond the team’s control. The importance of selecting a good project cannot be overemphasized.

Before the selected project starts, the selection team must identify the right improvement approach and assign the right personnel for that approach. Obviously, not every employee is an expert in every improvement methodology. Therefore, putting together a team with the right skills depends on the methodology selected. This principle not only takes project selection to a new level, but also puts the selection of both project and improvement approach ahead of personnel selection. Many organizations mistakenly begin with personnel selection.

This enhanced project selection process should identify the right projects that will deliver the following:

![]() Produce the highest value in relation to business goals

Produce the highest value in relation to business goals

![]() Improve performance of processes

Improve performance of processes

![]() Improve the flow of materials and information while reducing waste and cycle time

Improve the flow of materials and information while reducing waste and cycle time

Figure 2.4 schematically shows our recommended approach to selecting the right projects (Snee and Hoerl, 2007). It includes elements of both Six Sigma and Lean, with the ultimate goal of achieving maximum sustainable process improvements.

Figure 2.4 A novel approach to project selection within Lean Six Sigma

Within a Lean Six Sigma approach, process improvements typically result from three major types of projects, which require varying amounts of time for completion:

![]() Nike projects: Can be accomplished almost immediately. If they fail, they cost little in lost time and resources.

Nike projects: Can be accomplished almost immediately. If they fail, they cost little in lost time and resources.

![]() Lean projects: Often referred to as rapid improvement projects. These projects are typically completed in 30 days or less.

Lean projects: Often referred to as rapid improvement projects. These projects are typically completed in 30 days or less.

![]() Six Sigma projects: Typically are completed in three to six months, but can be completed even more quickly.

Six Sigma projects: Typically are completed in three to six months, but can be completed even more quickly.

Even within a Lean Six Sigma approach, numerous projects do not require the rigor of Six Sigma or Lean. These become quick hits, or Nike projects (Just Do It!). As Figure 2.4 suggests, all these types of projects are generated directly or indirectly from business goals or performance gaps. A top-down approach generates projects from business goals; a bottom-up approach addresses performance gaps that arise from within the operations of the organization. Business goals and performance gaps can directly generate Six Sigma projects, which is the customary approach for project selection in pure Six Sigma improvement systems. Note that this project selection process was specific to Lean Six Sigma. As we explain in subsequent chapters, this process needs to become much broader within a holistic improvement system. The principles stay the same, but obviously, there are many more options for types of projects.

Even in a holistic improvement system, goals and gaps can provide inputs for value stream mapping (VSM), a technique that is often employed in Lean but that can also be used to generate other types of projects (Martin and Osterling, 2013). For example, Six Sigma is typically used to address complex problems that have an unknown solution. If a VSM within a Lean project uncovers a complex problem with no known solution, a Six Sigma project might result. In the course of its execution, a Six Sigma project may uncover quick hits or generate Lean projects.

If VSM uncovers non-value-added activity for which Lean tools might be appropriate, then a Kaizen event might be convened to brainstorm solutions. (A Kaizen event is a focused project that takes place over one to three days, with improvements that are not only planned, but actually implemented.) That Kaizen event might then initiate a longer Lean project; alternatively, it might uncover a quick fix or might even find that there is no known solution, which would then generate a Six Sigma project.

Note that the category of Lean Six Sigma projects is conspicuously absent from the framework. This is because a Lean Six Sigma approach is essentially the integration of two methodologies, Lean Enterprise and Six Sigma. Individual projects are either more suited to a Lean approach, more suited to a Six Sigma approach, or perhaps quick hits (see Figure 2.4). They draw on a common toolbox that previously was separated according to methodology. Depending on the nature of the problem, of course, tools traditionally regarded as Lean tools or those associated with Six Sigma might dominate. Consider, for example, the types of commonly encountered improvement needs:

![]() Streamline process flow to reduce complexity, downtime, and cycle time, and to reduce waste

Streamline process flow to reduce complexity, downtime, and cycle time, and to reduce waste

![]() Improve product quality

Improve product quality

![]() Achieve consistency in product delivery

Achieve consistency in product delivery

![]() Reduce process and product costs

Reduce process and product costs

![]() Reduce process variation to reduce waste (such as the waste of defective products)

Reduce process variation to reduce waste (such as the waste of defective products)

![]() Improve process control to maintain stable and predictable processes

Improve process control to maintain stable and predictable processes

![]() Find the “sweet spot” in the process operating window

Find the “sweet spot” in the process operating window

![]() Achieve process and product robustness

Achieve process and product robustness

In all of these cases, as well as others, the nature of the improvement to be pursued and the root causes standing in the way of improvement help define the appropriate approach and tools to be used. When shifting the process average or reducing process variation is appropriate for the problem at hand, Six Sigma dominates. When improving process flow or reducing process complexity is appropriate, Lean tools dominate. Contrary to popular belief, however, both Lean and Six Sigma approaches can deal effectively with reduction of waste, cycle time, and non-value-added work (see Figure 2.5). This is additional proof that truly integrating Lean and Six Sigma can make available the best possible tools, regardless of their methodological origins. Hoerl and Snee (2013) provide more detail on selecting the most appropriate improvement methodology based on attributes of the problem.

Figure 2.5 Convergence of Six Sigma and Lean

Summary and Looking Forward

In this chapter, we discussed the critical principles of holistic improvement and examined how the approach works. This discussion included the following areas:

![]() Characteristics of holistic improvement

Characteristics of holistic improvement

![]() An overall strategic structure for holistic improvement

An overall strategic structure for holistic improvement

![]() Typical methodologies within each major building block of the overall strategic structure

Typical methodologies within each major building block of the overall strategic structure

![]() The case study in methodology integration provided by Lean Six Sigma

The case study in methodology integration provided by Lean Six Sigma

![]() Integrated project management systems

Integrated project management systems

In the next chapter, we discuss the key methodologies in Figure 2.1. Subsequent chapters look at the details of the infrastructure required for holistic improvement, such as systems for training, budgeting, tracking progress, and providing rewards and recognition.

References

George, M. L. (2002) Lean Six Sigma: Combining Six Sigma Quality with Lean Speed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hoerl, R. W., and Snee, R.D. (2013) “One Size Does Not Fit All: Identifying the Right Improvement Methodology.” Quality Progress (May 2013): 48–50.

Juran, J. (1989) Leadership for Quality: An Executive Handbook. New York: Free Press.

Kuhn, T. (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Martin, K., and M. Osterling. (2013) Value Stream Mapping: How to Visualize Work and Align Leadership for Organizational Transformation. New York: McGraw-Hill.

McGurk, T.L., (2014), “Ramping Up and Ensuring Supply Capability for Biopharmaceuticals”, Biopharm International, 17, 1, 38-44.

Snee, R. D. (2009) “Digging the Holistic Approach: Rethinking Business Improvement to Improve the Bottom Line.” Quality Progress (October 2009): 52–54.

Snee, R. D., and R. W. Hoerl. (2003) Leading Six Sigma: A Step-by-Step Guide Based on Experience with GE and Other Six Sigma Companies.New York: Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Snee, R. D., and R. W. Hoerl. (2005) Six Sigma Beyond the Factory Floor: Deployment Strategies for Financial Services, Health Care, and the Rest of the Real Economy. New York: Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Snee, R. D., and R. W. Hoerl. (2007) “Integrating Lean and Six Sigma: A Holistic Approach.” Six Sigma Forum Magazine (May): 15–21.

Snee, R. D., and R. W. Hoerl. (2017) “Time for Lean Six Sigma 2.0?” Quality Progress (May 2017): 50–53.

Welch, Jack. (2001) Jack Straight from the Gut. New York: Warner Books.