7

Managing the Effort

“Six Sigma works if you follow the process. If Six Sigma is not working, you’re not following the process.”

—AlliedSignal Manager

In the previous chapters, we discussed why the holistic improvement paradigm is needed, examined its building blocks, looked at case studies of its implementation, and shared tips on how to get started. In this chapter, we address how to manage the effort over time to realize its promised improved performance and to sustain it for the long term. This phase is of critical importance because, without it, your improvement initiative will dissipate over time, perhaps as soon as within two years. The elements of this phase are introduced and discussed here.

Your improvement initiative is now underway, initially focusing on Lean Six Sigma. The Executive and Champion workshops have been held. A deployment plan has been drafted, and an implementation plan is in place. The initial projects and Black Belts have been selected, and the first wave of training has been held. The initial wave of enthusiasm likely has carried the Lean Six Sigma effort this far. You are now reaching a critical transition point.

Once the first set of projects has been completed and the initiative begins to expand rapidly, you need to make the transition from a short-term launch to a well-managed long-term effort. The initiative will simply become too large to manage informally. You need a formal infrastructure to properly manage improvement deployment from this point onward. Otherwise, the initiative will become just another short-lived fad. You also need top talent in key leadership roles to implement the infrastructure and manage the effort.

We refer to this next step in the deployment process as managing the effort. Our guiding principle follows:

If you want something to happen on a regular and sustained basis, you need to have a management system in place to guide and sustain the effort.

Wikipedia (2011) defines a management system as a framework of processes and procedures used to ensure that an organization can fulfill all tasks required to achieve its objectives.

This phase goes roughly from completion of the initial wave of Black Belt training until we have trained everyone we originally intended to train and completed projects in all the areas mentioned in the deployment plan. It typically lasts a minimum of 18 months, although organizations must continue to manage Lean Six Sigma deployment in subsequent phases.

It is now time to put in place those systems and processes that will enable you to effectively manage the effort. You will have worked on many of these systems in the Executive and Champion workshops, and they are part of the deployment plan. At this point, you not only create systems to manage Lean Six Sigma, but you also begin to think about how to make these systems part of your culture—how you do things in your organization. This will help you sustain the benefits and make Lean Six Sigma “the way we work” (see Chapter 9, “The Way We Work”). Furthermore, during this phase, it is important to begin adding more elements of a holistic improvement system so that you expand beyond Lean Six Sigma to Lean Six Sigma 2.0, holistic improvement.

The following list, adapted from Snee et al. (1998), notes the key types of leadership support needed for successful Black Belt projects. Clearly, Black Belts cannot succeed on their own, and there is too much here to manage informally. Fortunately, your deployment plan can help you with each of these infrastructure elements. This chapter focuses on the elements of the deployment plan that are most needed at this point. Specifically, we discuss the following:

![]() Management project reviews

Management project reviews

![]() A project reporting and tracking system

A project reporting and tracking system

![]() A communications plan

A communications plan

![]() A reward and recognition plan

A reward and recognition plan

![]() A project identification/prioritization system

A project identification/prioritization system

![]() Project closure criteria

Project closure criteria

![]() Inclusion of Lean Six Sigma into budgeting processes

Inclusion of Lean Six Sigma into budgeting processes

![]() Deployment processes for Champions, Black Belts, MBBs, and so on

Deployment processes for Champions, Black Belts, MBBs, and so on

Implementation of these systems and processes is the key deliverable for this phase. Each of these infrastructure elements is an aspect of good management. When done well and integrated with your current management system, Lean Six Sigma becomes part of your culture. The goal is to make Lean Six Sigma part of how you do your work, not an add-on—eventually, it should not be something extra that you have to do (see Chapter 9). Before we discuss each of the listed elements and provide examples and guidance for its implementation, we comment on the role of managerial systems and processes to set the stage.

Leadership Support Needed for Successful Black Belt Projects

![]() Chartered project

Chartered project

![]() Identified, approved, and supported by management

Identified, approved, and supported by management

![]() Important to the organization—aligned with priorities

Important to the organization—aligned with priorities

![]() High impact (for example, more than $250,000 annual savings)

High impact (for example, more than $250,000 annual savings)

![]() Scope that can be completed in 3–6 months

Scope that can be completed in 3–6 months

![]() Clear quantitative measure of success

Clear quantitative measure of success

![]() Time for Black Belt to work on the project

Time for Black Belt to work on the project

![]() Recommend 100 percent dedicated, absolute minimum of 50–75 percent

Recommend 100 percent dedicated, absolute minimum of 50–75 percent

![]() Time for Black Belt to do the training and project work

Time for Black Belt to do the training and project work

![]() Reassignment of current workload

Reassignment of current workload

![]() Directions to form project team: typically 4–6 team members

Directions to form project team: typically 4–6 team members

![]() Access to people working on the process and others to be team members

Access to people working on the process and others to be team members

![]() Access to other specialists and subject matter experts

Access to other specialists and subject matter experts

![]() Guidance to keep the team small, to speed up progress

Guidance to keep the team small, to speed up progress

![]() Training for team members as needed

Training for team members as needed

![]() Priority use of organizational services such as lab services and access to the manufacturing line.

Priority use of organizational services such as lab services and access to the manufacturing line.

![]() Regular management reviews of the project

Regular management reviews of the project

![]() Weekly by Champion

Weekly by Champion

![]() Monthly by leadership team

Monthly by leadership team

![]() Help with data systems to collect needed process data on a priority basis

Help with data systems to collect needed process data on a priority basis

![]() Create temporary and manual systems as needed

Create temporary and manual systems as needed

![]() Communications—inform all persons affected by the project of:

Communications—inform all persons affected by the project of:

![]() Project purpose and value

Project purpose and value

![]() Need to support work of Black Belts

Need to support work of Black Belts

![]() Finance assistance in estimating and documenting bottom-line savings (in dollars)

Finance assistance in estimating and documenting bottom-line savings (in dollars)

![]() System to recognize, reward, and celebrate the success of the Black Belt and team

System to recognize, reward, and celebrate the success of the Black Belt and team

Managerial Systems and Processes

Most of this chapter discusses the implementation of managerial systems and processes. Because these terms are often used loosely in business circles, clarification is in order. All work is done through a series of processes. By process, we simply mean a sequence of activities that transform inputs (raw materials, information, and so on) into outputs (a finished product, an invoice, and so on).

There will always be a process, even if it cannot be seen and even if it is not standardized. In manufacturing, identifying the process is easy—just follow the pipes! Seeing the process is much more difficult in soft areas such as finance or legal. Understanding processes is critically important to making any improvement, however, because we improve outputs by improving the process. As noted earlier, process thinking is a fundamental aspect of Lean Six Sigma.

By managerial processes, we mean those that help us manage the organization, as opposed to making, distributing, or selling something. These typically include budgeting, reward and recognition, business planning, and reporting processes. Design and management of these processes generally define the core responsibilities of middle managers. Ideally, these processes help align all employees with strategic direction, such as by communicating or rewarding Lean Six Sigma successes. Poor managerial processes usually produce a dysfunctional organization, whereas effective managerial processes usually produce an effective and efficient organization.

Figure 7.1 illustrates what IBM considers to be its core business processes (IBM-Europe, 1990). The diagram separates the core processes into three major categories: product processes that involve design, production, and delivery of the organization’s products; general business processes that interact with the external marketplace, such as sales and marketing; and enterprise processes, which are the internal support processes that the customer does not usually see but that are required to keep the company running. Producing the company payroll is one example. Most of the managerial processes we discuss in this chapter fall into the category of enterprise processes, although the two other categories also have managerial processes.

Figure 7.1 IBM core processes

Often you will need to integrate several processes together to form a system. By system, we mean the collection of all relevant processes needed to complete some specific work. For example, your body has a cardiovascular system that performs the work of circulating blood. The beating of your heart is one process that is part of the cardiovascular system, but it cannot circulate blood effectively without the action of other muscles or the use of veins and arteries. All muscles, veins, and arteries, along with other parts of the cardiovascular system, must work in harmony for our blood to properly circulate. To return to the business world, most organizations have an overall reward and recognition system. Annual performance appraisal is typically one process in this system, but other processes are also needed to form an overall system.

An understanding of systems is important because you need to make sure that all processes are properly integrated for overall system optimization. It is common in the business word for people to optimize one process at the expense of others, resulting in poor overall system performance. For example, in a company’s sales system, four regional managers might compete with each other to land a national account; the net result could be a less profitable contract for the company. Each regional manager might have attempted to optimize his or her regional sales process, but did so to the detriment of the overall corporate sales system. This is called suboptimization, and it has been one of the central themes of management author Peter Senge’s work (Senge, 2006).

Improving systems can have a profound impact on entire organizations. It institutionalizes change because systems and their processes define how you do your work. It goes without saying that top talent in leadership roles is required to properly design, implement, and manage these systems.

In the discussion of Lean Six Sigma deployment, instances will undoubtedly arise when we use the word system but the reader feels process might be more accurate, and vice versa. This distinction is often gray. The key point is that we need a formal infrastructure, whether a process, a system, or some other mechanism, to effectively manage the effort. The specific term we use is not critical.

The key infrastructure elements are discussed in roughly the order in which they are typically considered in deployment.

Management Project Reviews

Management review is a critical success factor for Lean Six Sigma. Regular management review keeps the effort focused and on track. We know of no successful Lean Six Sigma implementation in which management reviews were not a key part of the deployment process. We refer to management reviews as the “secret sauce”—done regularly and at numerous levels, they significantly enhance the probability of success. I heard one CEO encourage his staff in this way: “Schedule reviews and show up. You don’t have to say anything. Good things will happen.”

We focus here on management project reviews, and we address management reviews of the overall implementation in Chapter 8, “Sustaining Momentum and Growing.” Project reviews should be done weekly and monthly; reviews of the overall initiative are preferably done quarterly or at least annually. We begin with management project reviews because you should already be reviewing the status of the initial wave of projects by this time.

Lean Six Sigma projects are most successful when Champions review them weekly and the business unit and function leaders review them monthly. Such a drumbeat prevents projects from dragging on and gives leadership early warning of any problems. A useful agenda for the Champion review follows:

![]() Activity this week

Activity this week

![]() Accomplishments this week

Accomplishments this week

![]() Recommended management actions

Recommended management actions

![]() Help needed

Help needed

![]() Plan for next week

Plan for next week

This review is informal and is not time consuming—it should take approximately 30 minutes. The idea is to have a quick check to keep the project on track by finding out what has been accomplished, what is planned, and what barriers need to be addressed. Typically, Champions guide only one or two Black Belts, so the time requirements are not great. These reviews help Champions fulfill their role of guiding the project and addressing barriers. Master Black Belts (MBBs) also attend these reviews as needed, and the MBB and Black Belt meet separately to resolve any technical issues that might have arisen.

All current projects are typically reviewed each month as well. This monthly review with the business unit or function leader is shorter than the weekly review, no more than 10 to 15 minutes per project. The purpose is to keep the project on schedule with respect to time and results, and to identify any problems or roadblocks. This review helps the business unit and functional leaders stay involved in Lean Six Sigma and directly informs them of any issues they need to address. A useful agenda for these reviews follows:

![]() Project purpose

Project purpose

![]() Process and financial metrics—progress versus goals

Process and financial metrics—progress versus goals

![]() Accomplishments since the last review

Accomplishments since the last review

![]() Plans for future work

Plans for future work

![]() Key lessons learned and findings

Key lessons learned and findings

Notice that this agenda is similar to the agenda for the weekly review with the Champion. In the monthly review, much more emphasis is placed on performance versus schedule, progress toward process and financial goals, and key lessons learned and findings.

As Lean Six Sigma grows, the number of projects could become large, requiring a lot of time for reviews. The review time can be reduced by rating projects as Green (on schedule), Yellow (in danger of falling behind schedule if something isn’t done), or Red (behind schedule and in need of help), and then reviewing only those rated as Red and Yellow.

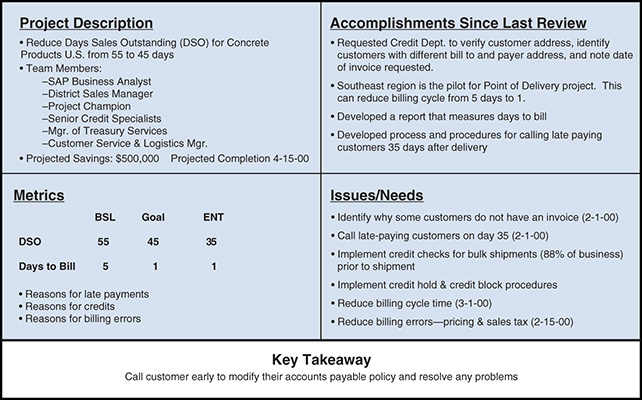

One way to increase the speed, clarity, and understanding of the review process is to use a common reporting format, such as the one in Figure 7.2. This format is similar to templates that GE, AlliedSignal, DuPont, and other companies use. An overall project summary is shown on one page using the four headings of Project Description, Metrics, Accomplishments, and Needs. Additional backup slides to support the material in the summary can be added as needed.

Figure 7.2 Example project status reporting form

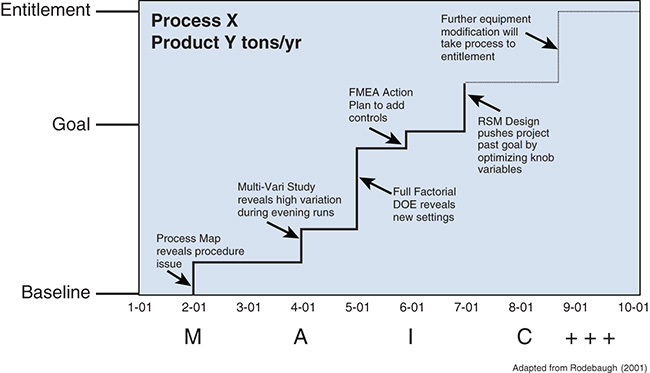

A good way to show progress toward entitlement is to use the graph in Figure 7.3 (Rodebaugh, 2001). A separate graph is used for each process measure impacted by the project.

Figure 7.3 Progress toward process entitlement for sample project

We all need feedback so that we know how we’re doing and how we can improve. Former New York City Mayor Ed Koch used to ask at every opportunity, “How am I doing?” The Beatles also needed feedback. The rock group’s last outdoor concert was held in Candlestick Park (San Francisco) in 1966. The crowd noise was extremely loud, so they knew their music was appreciated, but because of the noise, they couldn’t hear themselves sing; they had no direct feedback of their voices.

Without this feedback, the Beatles couldn’t monitor their own performance and improve it where necessary. This led them to discontinue outdoor concerts. Feedback provided during reviews is an important aid to improvement. Black Belts want and need feedback, and management reviews are one important form of providing it. Also, knowing that their projects will be reviewed by management provides significant motivation to Black Belts.

In all project reviews, it is important to ask questions to identify the methods, logic, and data used to support decisions. It is also important to pay attention to both social and technical issues. Sometimes the social concerns, such as interpersonal and interdepartmental relationships, as well as leadership skills, are more important than the technical issues.

It is also important to do a lot of listening. Open-ended questions (ones that cannot be answered yes or no) generally lead to more informative answers. Two helpful questions are, “Could you explain that in more detail?” and “Could you help me understand how you arrived at that conclusion?”

When you want to learn how the project—or any activity, for that matter—is progressing, ask two questions: “What’s working?” or “What are we doing well?” and then “What do we need to do better?” The answers will take you a long way toward understanding what is going on in the project or activity. A more detailed list of good questions to ask appears in Appendix A, “Ensuring Project and Initiative Success.”

The Black Belts, Champions, or a combination of Black Belts and Champions can present the project reports at the monthly reviews. Having the Champions give the reports involves them more deeply in the Lean Six Sigma initiative and increases understanding and ownership. When appropriate, Champions can report on several projects, reducing the amount of time required for the reviews. Project reviews are critical to success. Infrequent review of projects is a good predictor of a Lean Six Sigma initiative in trouble, as in the case studies of Royal Chemicals and Diversified Paper (Snee and Hoerl, 2003).

As noted previously, typically 30 to 50 percent of projects produce improvements that have bottom-line results even before the project is completed. Champions and other leaders should be on the lookout for such situations and make sure that the project, the Black Belt, and the Lean Six Sigma initiative get credit for the results as soon as possible. The weekly and monthly reviews are a good place to identify these opportunities and will speed up the impact of the Lean Six Sigma initiative.

Project Reporting and Tracking

As noted, it is important to have a regular drumbeat of reporting on the progress and results of projects. Developing a formal reporting and tracking system should therefore be an early priority during this phase of Lean Six Sigma deployment. The reporting system provides electronic or paper documents to back up and facilitate the project reviews.

The best reporting structure for Lean Six Sigma projects depends on the needs of the organization. A target frequency follows:

![]() Weekly highlights from the Black Belt to the Champion. A summary of the weekly review is usually sufficient for this purpose.

Weekly highlights from the Black Belt to the Champion. A summary of the weekly review is usually sufficient for this purpose.

![]() Monthly reports for the business or function leader, typically using information provided by the Champions.

Monthly reports for the business or function leader, typically using information provided by the Champions.

![]() Quarterly reports for corporate leadership, typically using information provided by the business and function leaders.

Quarterly reports for corporate leadership, typically using information provided by the business and function leaders.

The purpose of the reporting system is to keep the various levels of management informed of progress and results of the initiative. These reports also become the raw material for internal and external communications (see the upcoming “Communications Plan” section).

The reports should, of course, be designed to meet the needs of the organization. A good way to report on a project is to create a short summary of the project, analogous to the review template. Such a summary typically contains three parts: the problem/issue description, work done, and the results/impact/implications. Depending on the required length, it is usually appropriate to include a two- or three-sentence description for each of the three areas, plus relevant metrics and graphs. Your summary must include the results obtained in terms of improvement of process performance and bottom-line results. Lean Six Sigma is about getting results.

Typically, the Black Belt enters the project-level information into a computer system that can roll up the results across projects, functions, and business units, and drill down to greater detail on individual projects. Using workflow software, users can track the status of a project portfolio at a high level and also find links to additional, more detailed information, such as PowerPoint presentations or statistical analyses.

A key element of this reporting system is the financial tracking system. Leadership needs to know how the total bottom-line savings are progressing. By tracking the projects, leadership not only knows how the Lean Six Sigma initiative is performing, but also communicates the importance of the initiative to the organization. Recall the old saying: “What we measure and pay attention to gets done.”

Project tracking is typically led by finance because of the need to validate the financial data. Some key measures (English, 2001) that are typically tracked follow:

![]() Hard and soft dollar savings

Hard and soft dollar savings

![]() Number of projects completed

Number of projects completed

![]() Savings per project

Savings per project

![]() Projects per Black Belt and Green Belt

Projects per Black Belt and Green Belt

![]() Time to project completion

Time to project completion

![]() Number of Black Belts and Green Belts

Number of Black Belts and Green Belts

Leaders want reports of these measures for the whole organization, as well as the ability to drill down by business unit, function, plant or site, region of the world, country, and so on. Keeping track of a few projects is easy; an Excel spreadsheet usually does the trick. As the projects grow in number and as Lean Six Sigma moves throughout the organization, a more sophisticated system is needed. This system can be a database such as Lotus Notes, Microsoft Access, or Oracle, or software specifically designed for tracking Lean Six Sigma projects. We also know of instances when an existing project tracking system (such as for R&D projects) was enhanced to track Lean Six Sigma projects, thereby integrating Lean Six Sigma with existing management systems.

When tracking projects, people commonly ask, “How do I calculate the financial impact of a project?” Although the answer depends on the financial rules of each organization, we can provide some general guidance.

Financial impact is typically divided into hard and soft dollars (Snee and Rodebaugh, 2002). Hard dollars are dollars that clearly flow to the bottom line and will show up on the income statement and balance sheet. Examples include dollars from cost reductions, increased capacity that is immediately sold (because the product is in a sold-out condition), and decreased holding costs from increased inventory turns. As a general rule, companies report only the hard dollars as Lean Six Sigma savings because these are the funds that indisputably affect the profitability of the organization. For example, W. R. Grace reported a $26 million bottom-line impact in 2000 and an additional $7 million in cost avoidance (Snee and Hoerl, 2003).

Soft dollars are improvements in operations that do not directly affect the bottom line, but typically do so indirectly. Some examples are improving meeting efficiency so that less time is wasted in meetings, preventing problems that typically occur in new product introduction, and simplifying accounting processes so that fewer resources are needed to close the books. In each case, we could calculate a theoretical savings (in soft dollars) from the reduction of either the effort required or typical waste and rework levels. However, we cannot clearly demonstrate how these soft savings will show up on the balance sheet.

To clarify the difference between hard and soft dollars, consider a process that is improved and now requires three fewer people to operate it. If these three people are reassigned to other work, we have a cost avoidance (soft dollars). They are now freed to do more value-adding work to the benefit of the organization elsewhere. However, they are still employed and are still a cost to the organization, so we cannot claim hard dollar savings. On the other hand, if three positions are removed from the employee rolls after reassignment, we have a cost reduction (hard dollars) because we will clearly see this savings on our payroll expenses.

It is not unusual for a project to have both hard and soft dollar savings. It is also not unusual for the financial impact of a project to come from several different places. Black Belts and the financial organization should search for all possible sources of project impacts and capture the true savings, to make sure that no tangible savings are missed. Typically, the finance organization makes the final decisions about what qualifies as hard savings.

Communications Plan

We noted in Chapter 5, “How to Successfully Implement Lean Six Sigma 2.0,” that clear communication of the vision and strategy for Lean Six Sigma is a critical responsibility of leadership. Communication has a huge impact on the organization’s perception of Lean Six Sigma and, subsequently, on everyone’s receptiveness to it. We also noted that many organizations wait until they have achieved some tangible success before making major pronouncements about the initiative, so we did not address the communications plan until this chapter. The information provided here is relevant whenever leadership wants to begin formal communications about the effort.

The project reporting for management described in the previous section is one form of communication. In this section, we discuss communications more generally. We need to answer the following six questions to move toward designing an effective communications plan for Lean Six Sigma: Who? What? When? Where? Why? and How? The answers to these questions follow:

Question |

Answer |

Who? |

Different target audiences |

What? |

Lean Six Sigma need, vision, strategy, and results |

When? |

Continual, ongoing |

Where? |

In a variety of media |

Why? |

Set the tone, keep the organization informed |

How? |

Clear, concise, continual using a variety of media |

An informed organization will produce a more rapid, effective implementation of Lean Six Sigma. Many studies of change initiatives have demonstrated that people are more likely to embrace change when they understand the rationale, vision, and strategy of the change (Weisbord, 1989).

Fundamental to communicating well is recognizing that a lot of variation exists in both the information to be communicated and the target audiences. For example, the information that we need to communicate to the investment community is likely much different than the information we need to communicate to rank-and-file employees. The communications plan should take this type of variation into account. Communication is a process just like any other process used to run the business. Organizations have a variety of target audiences, each with different needs, wants, and desires. People are individuals who take in, process, and understand information in different ways. Their differences dictate that we utilize different media to communicate the message, even to the same target audience.

Note that leaders communicate by their actions—both what they do and what they say. Each contact, in person or otherwise, is an opportunity to communicate. Communication is a key responsibility of leaders, and they need to communicate their message over and over again, and in different ways, for it to be understood and internalized by the organization. People might have to hear something new at least five times before they internalize it. A message delivered only one time will likely go unnoticed.

The design of the communications plan depends on the organization. We summarize some communication principles here:

![]() We communicate by what we do and by what we say.

We communicate by what we do and by what we say.

![]() Use a variety of communication vehicles: face-to-face interaction, video, newsletters, memos, emails, skits, tweets, and pocket cards, among others.

Use a variety of communication vehicles: face-to-face interaction, video, newsletters, memos, emails, skits, tweets, and pocket cards, among others.

![]() Leaders must be seen and heard, as well as read.

Leaders must be seen and heard, as well as read.

![]() Communication has these characteristics:

Communication has these characteristics:

![]() An on-going process, not an event

An on-going process, not an event

![]() A two-way process—talk top-down, listen bottom-up

A two-way process—talk top-down, listen bottom-up

![]() A key aspect of leadership and a job responsibility

A key aspect of leadership and a job responsibility

![]() Also horizontal, employee to employee

Also horizontal, employee to employee

![]() Each contact is an opportunity to communicate.

Each contact is an opportunity to communicate.

![]() Leaders clarify complex issues.

Leaders clarify complex issues.

The following are communication methods:

![]() IT systems that share information throughout the organization, including customer views

IT systems that share information throughout the organization, including customer views

![]() Employee meetings to discuss strategic direction and initiatives

Employee meetings to discuss strategic direction and initiatives

![]() Periodic reports on the progress of projects and initiatives

Periodic reports on the progress of projects and initiatives

![]() Periodic reviews at all levels

Periodic reviews at all levels

![]() Act of connecting all initiatives to the strategic plan

Act of connecting all initiatives to the strategic plan

![]() Use of the strategic plan to guide work processes

Use of the strategic plan to guide work processes

![]() Behaviors that match the values of the organization

Behaviors that match the values of the organization

![]() Horizontal: employee to employee

Horizontal: employee to employee

![]() Visual management and measurement

Visual management and measurement

![]() Process management

Process management

![]() Communicates how we serve our customers

Communicates how we serve our customers

The next two lists illustrate specific examples of awareness training from one company (first list) and the outline of an overall communications plan in another company (second list). The first company decided to do a two-hour awareness training to introduce the organization to Lean Six Sigma.

Two-Hour Awareness Training for the Organization

![]() Creation of a standard script and visual aids for use by all managers

Creation of a standard script and visual aids for use by all managers

![]() Agenda: presentation followed by a question/answer session

Agenda: presentation followed by a question/answer session

![]() Feedback and follow-up

Feedback and follow-up

![]() Barriers and issues identified in question/answer session were collected and reviewed by senior management team, and needed actions were taken

Barriers and issues identified in question/answer session were collected and reviewed by senior management team, and needed actions were taken

Overall Communications Plan

![]() Plan covers the first 6–9 months

Plan covers the first 6–9 months

![]() Themes to be communicated

Themes to be communicated

![]() Lean Six Sigma tie to business strategy

Lean Six Sigma tie to business strategy

![]() Building on what was done before

Building on what was done before

![]() Goals

Goals

![]() Roles of individuals

Roles of individuals

![]() Media to be used

Media to be used

![]() Corporate and plant newspapers, Lotus Notes, bulletin board postings, staff meetings, corporate television, Lean Six Sigma website

Corporate and plant newspapers, Lotus Notes, bulletin board postings, staff meetings, corporate television, Lean Six Sigma website

![]() Topics for first 9 weeks

Topics for first 9 weeks

![]() Lean Six Sigma strategy and goals

Lean Six Sigma strategy and goals

![]() Meet the Lean Six Sigma Champions

Meet the Lean Six Sigma Champions

![]() How other companies are using Lean Six Sigma

How other companies are using Lean Six Sigma

![]() Customer feedback surveys

Customer feedback surveys

![]() Lean Six Sigma improvement process

Lean Six Sigma improvement process

![]() How projects are being selected

How projects are being selected

![]() How Lean Six Sigma is different

How Lean Six Sigma is different

![]() Executive, Champion, and Black Belt training

Executive, Champion, and Black Belt training

![]() How Lean Six Sigma will affect the organization

How Lean Six Sigma will affect the organization

![]() Periodic communications as needed

Periodic communications as needed

![]() Answers to frequently asked questions

Answers to frequently asked questions

![]() Comments from the president

Comments from the president

![]() Results of Lean Six Sigma projects

Results of Lean Six Sigma projects

![]() Success stories and celebrations

Success stories and celebrations

![]() Lean Six Sigma financial updates

Lean Six Sigma financial updates

Note that the awareness session followed the principles that communication is a process and is two-way: delivering and receiving. An awareness session usually answers these questions:

![]() What is Lean Six Sigma?

What is Lean Six Sigma?

![]() Why are we pursuing Lean Six Sigma?

Why are we pursuing Lean Six Sigma?

![]() How will we deploy Lean Six Sigma?

How will we deploy Lean Six Sigma?

The answers are intended to communicate the organization’s rationale for deploying Lean Six Sigma, its vision, and its overall strategy. This is a critically important message and should be an integral part of any communication plan. Our experience is that it usually takes two to four hours for a group of any size to develop a useful awareness of Lean Six Sigma.

The second plan had a time frame of the first six to nine months of deployment. Note that the plan did not contain any awareness training. Those participating in the Executive and Champion workshops were told to do awareness training for their organizations using the materials they had received in the workshops. This unique approach illustrates how organizations differ in their deployment of Lean Six Sigma.

Some organizations prepare presentations for the managers to use to communicate Lean Six Sigma. Other companies ask the managers to prepare their own awareness materials. Both approaches have pros and cons. A common presentation helps ensure a consistent message. However, managers who prepare their own awareness training will develop a deeper understanding of Lean Six Sigma in the process. Because first impressions often last, we recommend using common materials to hit the rationale, vision, and strategy, combined with tailored materials for each organization developed by its own management.

Reward and Recognition Plan

As we noted in Chapter 5, we believe that the most effective motivation is intrinsic motivation—that is, people doing something because they believe in it or want to do it. For example, history shows that mercenary armies have never performed well against armies that believed in what they were fighting for. On the other hand, if there are no tangible rewards for accomplishments in Lean Six Sigma, this omission will essentially be a demotivator. People might say, “I would love to be involved in Lean Six Sigma, but I’m concerned about what it might do to my career.”

We must balance intrinsic motivation with extrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation means providing a carrot or stick to motivate someone to do something they would not do otherwise, such as rewarding children for cleaning their rooms. Providing extrinsic motivation helps ensure that there are no barriers to top talent getting involved in Lean Six Sigma.

We are all motivated to work on those things that will be beneficial to our career. This fact leads us to consider what reward and recognition system we will use to support Lean Six Sigma. In fact, some companies have the reward and recognition plan for Lean Six Sigma designed even before deployment. Jack Welch said about GE, “As with every initiative, we backed Lean Six Sigma up with our rewards system” (Welch, 2001). This included basing 40 percent of the annual managerial bonus on Lean Six Sigma results, providing stock option grants for MBBs, and requiring Green Belt certification for promotion.

Every successful implementation of Lean Six Sigma we are familiar with has developed a special reward and recognition system to support Lean Six Sigma. Conversely, during previous improvement initiatives (such as TQM), leadership might have stated that it wanted one behavior (such as quality improvement) but rewarded something totally different (such as meeting the financial numbers). Such disconnects between leadership’s words and actions are immediately obvious to employees and can lead to cynicism.

The reward and recognition system is a statement by leadership about what it values and is a much more important document than a printed values statement. Leaders must think carefully about the message they want to convey.

As with communications, the form of the reward and recognition plan is greatly dependent on the culture and existing plan of the company involved. Some companies choose to use their existing system because they feel it has the capability to adequately reward the contributions of those involved in Lean Six Sigma. This can be the case in some instances, but in general, a special reward and recognition system should be developed. The following list summarizes the Black Belt recognition program for one company we have worked with. This plan recognizes that Black Belts are critical to our success and that special rewards are needed to ensure that top performers are eager to take this role. Unfortunately, this plan makes no mention of rewarding others involved in Lean Six Sigma work.

![]() Base pay

Base pay

![]() Potential increase at time of selection

Potential increase at time of selection

![]() Retain current salary grade

Retain current salary grade

![]() Normal group performance review and merit pay

Normal group performance review and merit pay

![]() Incentive compensation

Incentive compensation

![]() Special plan for Black Belts

Special plan for Black Belts

![]() Target award at 15 percent of base pay

Target award at 15 percent of base pay

![]() Performance rating on 0–150 percent of scale

Performance rating on 0–150 percent of scale

![]() Measured against key project objectives

Measured against key project objectives

![]() Participation ends at end of Black Belt assignment

Participation ends at end of Black Belt assignment

The Lean Six Sigma reward and recognition plan for another company is summarized next. Note the completeness of this plan, including recognition of Green Belts and team members (including MBBs and Champions), as well as an annual celebration event complete with leadership participation.

![]() BB Selection: Receive Lean Six Sigma pin

BB Selection: Receive Lean Six Sigma pin

![]() BB Certification: $5,000 certification bonus, plus plaque

BB Certification: $5,000 certification bonus, plus plaque

![]() BB project completion

BB project completion

![]() $500 to $5,000 in cash or stock options for first project

$500 to $5,000 in cash or stock options for first project

![]() Plaque with project name engraved for first and subsequent projects

Plaque with project name engraved for first and subsequent projects

![]() BB Lean Six Sigma activity awards

BB Lean Six Sigma activity awards

![]() Recognizes efforts and achievements during projects with individual and team awards (cash, tickets, dinners, shirts, and so on)

Recognizes efforts and achievements during projects with individual and team awards (cash, tickets, dinners, shirts, and so on)

![]() Green Belt recognition

Green Belt recognition

![]() Similar to Black Belt recognition

Similar to Black Belt recognition

![]() No certification bonus

No certification bonus

![]() Project team member recognition

Project team member recognition

![]() Similar to BB and GB recognition

Similar to BB and GB recognition

![]() No certification awards

No certification awards

![]() Annual Lean Six Sigma celebration event

Annual Lean Six Sigma celebration event

![]() Presentation of key projects

Presentation of key projects

![]() Dinner reception with senior leadership

Dinner reception with senior leadership

Note also that not all rewards have to be monetary. For many people, peer and management recognition, such as an opportunity to present their project, is a greater reward than money.

In evaluating these reward and recognition plans, as well as those of other organizations, we conclude that the most appropriate plan is company dependent. What works for one company, or even one employee, will not necessarily work for another. Reward and recognition plans are also not static. The points listed here will likely change over time as experience with Lean Six Sigma grows and the reward and recognition needs become clear. The one constant is to make sure you are rewarding the behavior you want to encourage.

Lean Six Sigma goals and objectives should be part of performance plans for all those involved in the Lean Six Sigma initiative. If the company intends for Lean Six Sigma to involve the entire organization, then these goals and objectives must be included in the performance plans for the entire organization. This is consistent with our earlier recognition that we are all motivated to work on the things that will be beneficial to our career. Lean Six Sigma responsibilities should be part of people’s individual goals and objectives, and their performance should be evaluated relative to these goals and objectives. Once again, what management measures and pays attention to gets done.

Project Identification and Prioritization

Improvement project management has many aspects. A system is needed for project identification and prioritization to effectively manage the many moving parts.

We discussed initial project selection in Chapter 5. When the Black Belts have completed their first projects, they are ready to take on another project. You don’t want to lose any momentum. After this new project has gotten underway, full-time Black Belts will be ready to take on a second project simultaneously. This ramp-up will continue until fully operational Black Belts are handling three or four projects at a time.

Clearly, with a lot of Black Belts working in an organization, you need to plan carefully to ensure that you have important, high-impact projects identified and ready to go when the Black Belts are ready. A frequent mistake companies make is waiting for the Black Belt to finish a project before looking for another one. Such a strategy wastes the time of the Black Belts, a valuable resource. A Black Belt without a project is a sin in the Lean Six Sigma world. Lack of planning also often results in mediocre projects because insufficient thought had been put into the selection process. Good project selection is a key to success.

Now that you have numerous projects and Black Belts, you cannot rely on ad-hoc project selection, but instead must implement a formal selection and prioritization system. Figure 7.4 shows a schematic of an ongoing project selection process and its associated project hopper (Rodebaugh, 2001). Project selection should be an ongoing process that ensures we always have a collection of projects ready for Black Belts to tackle. One strategy for keeping the project hopper “evergreen” is to require that a new project be added to the hopper each time a project is removed and assigned to a Black Belt or Green Belt.

Figure 7.4 Project selection and management process system

The project hopper can be thought of as an organizational to-do list and should be managed in much the same way. Projects are continually being put into the hopper, the list is continually being prioritized, and prioritized projects are assigned to Black Belts or Green Belts as these resources become available. By continually searching for projects and reprioritizing the list of projects in the project hopper, you ensure that problems most important to the organization are being addressed using Lean Six Sigma.

When considering project identification, two important sources are often overlooked in Lean Six Sigma but should be considered: Big Data and risk management. A Big Data project (see Chapter 3, “Key Methodologies in a Holistic Improvement System”) typically produces several subprojects that should be addressed using Lean Six Sigma. As previously noted, Big Data analytics provide important opportunities for improvement that should be integrated with other improvement efforts instead of creating an isolated “island of improvement” or even becoming a “competitor” to the Lean Six Sigma initiative. Utilizing input from Big Data projects for Lean Six Sigma project selection provides an early opportunity for integration. Similarly, risk management (discussed further in Chapter 9) is a business need that is relevant to all processes and business functions. The associated risk assessments result in several opportunities for improvement that generate projects to be added to the project hopper.

Each business or functional unit should have a project hopper. It is also appropriate to have a corporate project hopper to handle projects that do not naturally fit into the hoppers of the business and functional units. For example, a project to improve integration of business units or functions does not fit squarely within any one business or function. The hopper should always be full, containing at least a six-month supply of projects (a year’s supply is even better) and at least one project that would naturally fit into the work of each individual Black Belt. As noted earlier, Black Belts should never be without a full load of projects. It is important to review the hopper contents as part of the quarterly Lean Six Sigma initiative review (discussed further in Chapter 8).

The discussion of initial project selection in Chapter 6, “Launching the Initiative,” provided most of the guidelines for project selection. These apply to the ongoing project selection and prioritization system as well. We recommend focusing projects strategically on business priorities and also wherever the organization is experiencing significant pain, such as responding to critical customer issues. Information that is helpful in selecting specific projects is contained in the baseline and entitlement database. This data tells you how the processes are performing today and how they could be performing in the future; it also identifies the sources of important improvement opportunities.

Process baseline and entitlement data should be maintained and updated for all key process performance metrics associated with the manufacturing and nonmanufacturing processes used to run the organization. The job of creating and maintaining this database is typically assigned to an MBB or experienced Black Belt. Depending on the level of complexity, the information technology group might actually develop the system or might assume long-term responsibility to maintain it. This database should be updated every six months or so and be included in at least every other quarterly Lean Six Sigma initiative review (see Chapter 8).

The development and maintenance of such databases is simply good management practice, but our experience is that typically they don’t exist at all or they focus solely on accounting information and, therefore, are inadequate for improvement purposes. Lack of good data is probably the greatest challenge Black Belt teams face. This is one reason evaluation of the measurement system is a key element of the Measure phase of DMAIC projects.

When you have spent time and effort developing an adequate measurement system for improvement purposes, you should make sure it is properly integrated with existing information systems and is maintained so that you don’t have to re-create the system for future projects.

Project Closure: Moving On to the Next Project

Project closure is an important event. It is the signal that the project is completed, that the Black Belt can move on to the next project, and that you can “ring the cash register” with money flowing to the bottom line. Project closure criteria form an important part of the project identification and prioritization system because they help Black Belts and others move on to their next projects promptly. They should neither linger on projects too long nor leave prematurely before critical controls are in place.

Some perfectionists will not want to move on until they have reached entitlement, even though they have met their original objectives and bigger issues are emerging elsewhere. Other Black Belts or Green Belts might be eager to tackle the next problem and want to leave before critical controls are in place. The key players in this event are the Black Belt or Green Belt, the Champion, the finance representative, and the person who owns the process. The process owner is needed because the process improvements developed by the Black Belt or Green Belt will become standard operating procedure for the process in the future.

The key to project closure is verification of the process improvements and associated financial impact (determined by finance), completion of the process control plan, completion of the training associated with the new way of operating, and completion of the project report that summarizes the work done and the key findings. When this work is done, the Black Belt or Green Belt often makes a presentation to management; the rest of the organization is informed through the project reporting system or other methods of communication (newsletters, websites, storyboards, and so on).

You can manage project closure by having a standard set of steps to close out a project, a project closure form that is an integral part of the project tracking system, and a method for electronically archiving the project in the reporting system so the results are available to the whole organization. This last item is important because Black Belts working in nonstandard areas such as risk management find documentation of previous projects in this same area extremely helpful. The specific closure steps and form should be tailored to each organization, but we recommend that the following steps be required:

![]() Successful completion of each phase of the DMAIC (or DFSS) process

Successful completion of each phase of the DMAIC (or DFSS) process

![]() Finance sign-off on the savings claimed

Finance sign-off on the savings claimed

![]() A control plan in place and being used by process owner

A control plan in place and being used by process owner

![]() Any needed training implemented

Any needed training implemented

![]() Final Champion and management reviews

Final Champion and management reviews

Lean Six Sigma Budgeting

Most organizations that implement Lean Six Sigma do not have the implementation costs or benefits in their budget at the time they decide to launch. This happens simply because most didn’t realize in the previous year, when the current year’s budget was developed, that they would be implementing Lean Six Sigma now. Therefore, Lean Six Sigma is generally launched with special funding allocated by senior leadership. This is certainly acceptable to get started, but as organizations begin to formally manage the effort, it is critically important that Lean Six Sigma be included in their key budgeting processes.

This inclusion is important for several reasons. First, leadership needs to make sure that Lean Six Sigma receives the same degree of financial scrutiny as any other budgetary area. Virtually all public corporations, and most private and even nonprofit organizations, have existing budgeting and financial control systems in place, so they can simply include Lean Six Sigma in these instead of having to create a new infrastructure.

Second, inclusion into the budget helps Lean Six Sigma move from being viewed as a separate, potentially short-term initiative, to being a normal part of how you work.

Third, this budget documents and formalizes leadership expectations of all layers of management. These expectations are clear when each business unit budget shows a line item for financial benefits from Lean Six Sigma, in addition to a line item for expenditures for Lean Six Sigma. Leadership is providing financial resources to implement Lean Six Sigma, but it expects a payoff. Ideally, business unit managers will be intrinsically motivated to enthusiastically deploy Lean Six Sigma because they believe in what it can do. However, just in case some managers are not, knowing that they are accountable for obtaining financial benefits through Lean Six Sigma will provide significant extrinsic motivation to succeed.

Deployment Processes for Leaders

After you have selected your first group of Champions, Black Belts, and other roles in this phase of launching the initiative, these team members will begin working on their initial projects. We explained in Chapter 5 how to go about initial project and people selection. During the phase of managing the effort, however, the number of projects will be growing too quickly to pick Black Belts and others on an ad hoc basis. You need to develop a formal process for selecting Black Belts and other roles and then assigning them to projects.

This process will become even more important later, as Black Belts begin rotating out of their assignments and need to be replaced. It might be appropriate for some Black Belts to remain in their role for many years. However, the world is dynamic, and Black Belts will leave the initiative for a variety of reasons, just as people leave other assignments over time. A few will leave because they are not suited for the work; others will leave because of a transfer or promotion. A few will become MBBs; some will move on to other companies and other careers.

A formal process, typically led by human resources (HR) personnel, must continually look at the improvement needs of the organization (for example, strategy and project hopper contents) and the career development needs of the top performers in the organization, and then select the ones who should take Champion, Black Belt, MBB, or other Lean Six Sigma roles.

This process also looks to move top Green Belts into Black Belt roles, Black Belts into MBB roles, and so on. After about two years into the initiative, Black Belts and others will begin to rotate out of Lean Six Sigma roles and will be looking for big jobs. It is important to have a placement process ready to properly place them into important roles.

As noted in our discussion of reward and recognition, people need tangible evidence that making the commitment to Lean Six Sigma will help their careers. Seeing others get big and important jobs after their Lean Six Sigma assignment is one way to make this happen. Conversely, if you do not place these resources in important positions, you will be wasting the significant leadership development they have received.

HR might primarily manage the people selection process, or this could be managed by a business Quality Council with support from HR. Most organizations soon see the need for an active, formal Lean Six Sigma organization to effectively manage many of these systems and processes (see Chapter 8). The people selection process should follow the criteria given in Chapter 5 for the selection of Black Belts and others. The process of assigning these resources to projects should be based on the project identification and prioritization system. In other words, you should first select the projects and then select the appropriate Black Belts to work on them. Such an approach simplifies the process of assigning Black Belts after they have been selected.

The placement process for those rotating out of Lean Six Sigma roles often presents a greater challenge because big jobs are few in number; there might not be a suitable job waiting for each Black Belt or MBB rotating out. Therefore, many companies make the timing flexible, allowing Black Belts and others to begin looking for their next job after about 18 months, while still in their Lean Six Sigma position. This enables them to wait until they find a good fit and still complete their current project.

Initially, HR might need to help those leaving Lean Six Sigma roles obtain the job they desire. After a while, managers will be actively seeking Black Belts and MBBs with no prompting from HR because they will see how these assignments have grown and matured the people in them. Recall from Chapter 3 that a key benefit of Lean Six Sigma is that it becomes an excellent leadership development system for top talent.

Integrating Lean Six Sigma with Current Management Systems

Organizations should look for every opportunity to integrate Lean Six Sigma management systems with their current management systems. Integration will help make Lean Six Sigma part of their culture, reduce bureaucracy and the amount of effort needed to manage the initiative, and increase its impact. This approach to integration is discussed in detail in Chapter 9, which shows how to make the transition from Lean Six Sigma being an initiative to holistic improvement being the way you work. However, you should begin integrating Lean Six Sigma now, at the point when you implement Lean Six Sigma management systems. The more integration you do now, the less you will have to do later.

For example, Lean Six Sigma reviews can become part of normal staff and management meetings, as long as they are given adequate time on the agenda. As noted, Lean Six Sigma should be part of your budgeting processes, not a standalone item. In some companies, Lean Six Sigma identifies a gap in the communications process that has to be filled by creating new media. We noted previously that the reward and recognition system usually has to be revised to support the needs of Lean Six Sigma, but there will eventually be only one reward and recognition system. Most organizations will need to create a project tracking system. In some instances, existing project management systems can be enhanced to enable Lean Six Sigma project tracking.

In most cases, project closure procedures and supporting forms have to be created and integrated with the project tracking system. The project selection process and its associated project hopper also have to be created in most organizations. Whenever possible, the project selection process should be integrated with the capital project system and other, similar systems. Early focus on integrating Lean Six Sigma managing processes with current systems greatly speeds up acceptance of the methodology and its bottom-line impact, not to mention simplifying the final transition to the way you work.

Summary and Looking Forward

We define the phase of managing the effort to be the period between completion of the initial wave of Black Belt training and the point when you have trained everyone originally intended and implemented all projects identified in your original deployment plan. This phase typically lasts about 18 months, although management of the effort lasts indefinitely.

The critical transition that occurs here is from a new launch to a formal long-term initiative. The effort will become too large to manage informally and will require the implementation of formal management systems and processes. These systems and processes are all infrastructure elements of the deployment plan discussed in Chapter 5.

The key deliverable is implementation of these infrastructure elements, which typically include the following:

![]() Management project reviews

Management project reviews

![]() A project reporting and tracking system

A project reporting and tracking system

![]() A communications plan

A communications plan

![]() A reward and recognition plan

A reward and recognition plan

![]() A project identification and prioritization system

A project identification and prioritization system

![]() Project closure criteria

Project closure criteria

![]() Inclusion of Lean Six Sigma into budgeting processes

Inclusion of Lean Six Sigma into budgeting processes

![]() Deployment processes for Champions, Black Belts, MBBs, and so on

Deployment processes for Champions, Black Belts, MBBs, and so on

Obtaining top talent for key Lean Six Sigma roles and implementing this key infrastructure are key success factors in this phase. Top talent is needed to properly design, implement, and manage these systems and processes. Designing management systems is not easy work, and a poor system can negatively impact the entire organization. Other important success factors in this phase include the following:

![]() Making improvement opportunities possible with a good process baseline and entitlement database.

Making improvement opportunities possible with a good process baseline and entitlement database.

![]() Using Lean Six Sigma assignments as a leadership development system.

Using Lean Six Sigma assignments as a leadership development system.

![]() Integrating Lean Six Sigma management processes into normal operating procedures. This reduces the effort required to manage the initiative, reduces bureaucracy, and sets the stage for making Lean Six Sigma the way we work.

Integrating Lean Six Sigma management processes into normal operating procedures. This reduces the effort required to manage the initiative, reduces bureaucracy, and sets the stage for making Lean Six Sigma the way we work.

In the next chapter, we discuss how to sustain the momentum of the improvement initiative over time and expand to a more holistic approach: Lean Six Sigma 2.0. This enables the improvement initiative to grow in its effectiveness, maintaining the bottom-line improvements established by the improvement projects and extending the improvement initiative to new problems and improvement opportunities.

References

English, W. (2001) “Implementing Lean Six Sigma: The Iomega Story.” Presented at the Conference on Lean Six Sigma in the Pharmaceutical Industry, Philadelphia, PA, November 27–28, 2001.

Rodebaugh, W. R. (2001) “Lean Six Sigma in Measurement Systems: Evaluating the Hidden Factory.” Presented at the Penn State Great Valley Symposium on Statistical Methods for Quality Practitioners, Malvern, PA., October 2001.

Senge, P. (2006) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. Revised ed. New York: Doubleday/Currency.

Snee, R. D., and R. W. Hoerl. (2003) Leading Six Sigma: A Step-by-Step Guide Based on Experience with GE and Other Six Sigma Companies. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Snee, R. D., K. H. Kelleher, and S. Reynard. (1998) “Improving Team Effectiveness.” Quality Progress (May): 43–48.

Snee, R. D., and W. F. Rodebaugh. (2002) “Project Selection Process.” Quality Progress (September): 78–80.

Weisbord, M. R. (1989) Productive Workplaces. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Welch, J. F. (2001) Jack, Straight from the Gut. New York: Warner Business Books.