9

The Way We Work

“With Lean Six Sigma permeating much of what we do, it will be unthinkable to hire, promote, or tolerate those who cannot, or will not, commit to this way of working.”

—Jack Welch, former CEO, General Electric

In Chapters 7, “Managing the Effort,” and 8, “Sustaining Momentum and Growing,” we discussed managing the Lean Six Sigma initiative, sustaining the gains, expanding the initiative by incorporating additional improvement methods, and expanding to all parts of the enterprise (including suppliers and customers). A central theme was the need to integrate Lean Six Sigma activities with quality by design and quality and process management efforts.

In this chapter, we take Lean Six Sigma one step further and discuss how to integrate it into daily work processes. The changes an organization makes in its work as a result of Lean Six Sigma 2.0 comprise its control plan for the overall initiative and ensure that it maintains the gains it has achieved. The desired end game is that holistic improvement becomes such an integral part of the way the organization manages that there is no longer a need for a formal Lean Six Sigma initiative. Instead, there is a holistic improvement organization that is a stable and integral part of the company, analogous to finance, human resources, marketing, and so on.

The recognition that Lean Six Sigma 2.0 has been institutionalized into your culture is not based on a Gantt chart or a predetermined deadline. You will know that you have achieved true holistic improvement when you see the key elements of Lean Six Sigma 2.0 being used on a daily basis. Some examples include the following:

![]() Continuously working to find better ways of doing things

Continuously working to find better ways of doing things

![]() Recognizing the importance of the bottom line and finding ways to improve it

Recognizing the importance of the bottom line and finding ways to improve it

![]() Thinking of everything you do as a process

Thinking of everything you do as a process

![]() Working to reduce variation and risk

Working to reduce variation and risk

![]() Using data to guide your decisions

Using data to guide your decisions

![]() Using diverse methods and tools to make your processes more effective and productive

Using diverse methods and tools to make your processes more effective and productive

![]() Integrating quality by design activities with breakthrough improvement and quality and process management, all within one organizational umbrella

Integrating quality by design activities with breakthrough improvement and quality and process management, all within one organizational umbrella

These key elements will be clearer as we discuss ways of making Lean Six Sigma 2.0 part of daily work processes.

In our experience, the best way to make holistic improvement a reality is by integrating Lean Six Sigma with other improvement approaches, including quality by design and quality and process management. This integration results in the creation and management of an overall improvement system. This system is then responsible all types of organizational improvement. This includes ISO 9000 and the Malcolm Baldrige Award assessment, in the area of process management, as well as new product development and DFSS, in the area of quality by design.

Creating a Holistic Improvement System

As discussed previously, we often see diverse improvement activities compete for resources and management attention, resulting in unhealthy “islands of improvement.” From the beginning of Lean Six Sigma deployment, the long-term goal has been to combine all improvement initiatives into one holistic improvement system that has Lean and Six Sigma as integral components. Furthermore, the supporting management systems and structure required to sustain this system over time need to be put in place. When this work is done, true holistic improvement, or Lean Six Sigma 2.0, has been achieved. Table 9.1 re-emphasizes the needs and methods of the overall improvement system that we initially presented in Chapter 2, “What Is Holistic Improvement?”.

Table 9.1 Holistic Improvement System Needs and Sample Approaches

The intent is for improvement to become a core business function within the management system, on equal footing with finance, human resources, information technology, marketing, manufacturing, and so on. Going forward, the company would have no individual improvement initiatives, such as Lean Six Sigma and ISO 9000, but would instead have one holistic improvement system that is a permanent part of the management system. We discuss more details of this organization shortly. First, however, we discuss the lynchpin of the holistic improvement system: the improvement project portfolio.

The Improvement Project Portfolio

Key to making such a holistic improvement system work is having all improvement ideas come through one organization, to be prioritized based on their potential impact on the organization instead of based on organizational or political boundaries. During the organization’s annual planning process, all potential improvement projects are placed into one improvement project hopper, which is then prioritized based on business need and impact. Only the highest-prioritized ideas are funded and placed into the improvement project portfolio—that is, the portfolio of projects selected for implementation.

The improvement organization then selects the most promising improvement methodology for the project, which could be Six Sigma, Work-Out, Lean, or some other approach. An appropriate Black Belt who is knowledgeable in that methodology is assigned, and the company provides additional resources, including funding and team members. Note that there is still competition between potential projects, but it is a healthy competition of ideas within one organization, with all ideas on an equal planning field. Note also that the project could simply be a “Nike project” (Just Do It!), which requires only project management and not a formal improvement methodology.

The improvement project portfolio needs to be dynamic; as one project finishes, a new project is added. Of course, much can change after the annual planning is completed, so relative priorities of projects could also change as new situations occur or new information becomes available. The annual planning simply sets the stage at the beginning of the year.

Some guiding principles for developing and maintaining the improvement project portfolio follow:

![]() Improvement and growth occur project by project.

Improvement and growth occur project by project.

![]() A project is a problem scheduled for solution.

A project is a problem scheduled for solution.

![]() Projects come from many different sources and should be managed by a common system.

Projects come from many different sources and should be managed by a common system.

![]() Effective project management skills are needed for successful projects.

Effective project management skills are needed for successful projects.

![]() Projects should be linked to the strategic needs and priorities of the organization.

Projects should be linked to the strategic needs and priorities of the organization.

![]() Continual review, assessment, and evaluation of the combined list of projects will keep it up-to-date.

Continual review, assessment, and evaluation of the combined list of projects will keep it up-to-date.

![]() As in investment portfolios, the focus should be on balancing the overall portfolio to best achieve the organization’s objectives.

As in investment portfolios, the focus should be on balancing the overall portfolio to best achieve the organization’s objectives.

The organization’s improvement portfolio generally includes a mixture of projects in the three main categories shown in Table 9.1:

![]() Quality by design projects, which typically offer the potential for innovation and top-line growth

Quality by design projects, which typically offer the potential for innovation and top-line growth

![]() Breakthrough improvement projects, often intended to drive significant bottom-line improvement

Breakthrough improvement projects, often intended to drive significant bottom-line improvement

![]() Projects intended to enhance the organization’s quality and process management excellence

Projects intended to enhance the organization’s quality and process management excellence

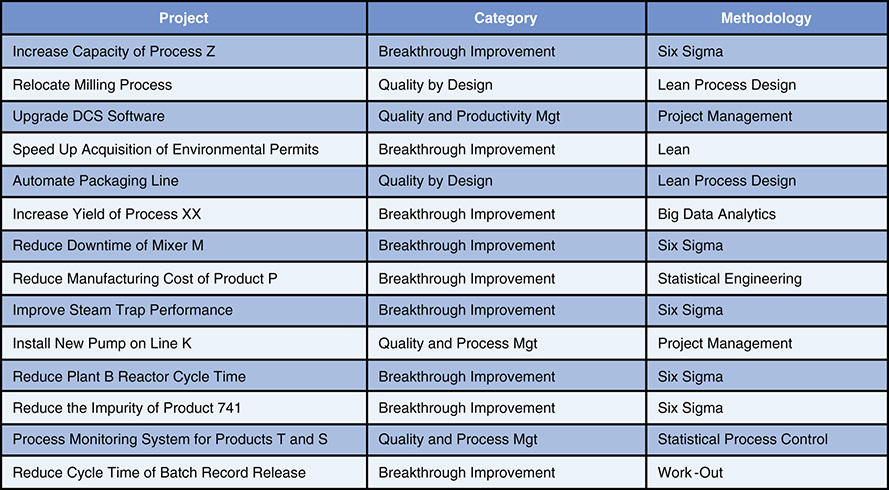

Table 9.2 shows a simple example of an improvement project portfolio of 14 projects. (Note that actual portfolios typically are much longer than Table 9.2, which is for illustrative purposes only.) Putting all improvement projects in a single list aids the budgeting process and focuses the organization on what needs to be done, given the available resources.

Table 9.2 Holistic Improvement System Needs and Sample Approaches

In some cases, planners charter a breakthrough improvement project to assess whether the solution proposed by the quality by design project (which can require significant capital) is actually the best solution. For example, a Six Sigma project could achieve the same level of improvement without significant capital investment. Planners might want to make sure the process is at entitlement before they spend significant capital to upgrade it or expand capacity.

The Improvement Organization

As noted earlier, in a holistic improvement system, all improvement projects are managed by one organization, which we refer to as the improvement organization. Some companies refer to this as the quality organization, but this term can be limiting because of how traditional quality organizations are structured. For example, most employees do not think of the quality organization being responsible for innovation or growth. Using the term improvement organization can help employees understand that this group has broader accountability than traditional quality organizations.

Typically, quality by design activities are managed by marketing or perhaps research and development (R&D), and quality and process management activities are managed by the quality or process control organizations. As previously discussed, this often leads to unhealthy competition based on politics and organizational boundaries instead of fostering a competition of ideas on a level playing field. Therefore, a new organization should be created to both provide such a level playing field and offer a strategic view of improvement across the “islands of improvement.”

In our view, the quality organization (as well as Lean or Six Sigma organizations, if they exist) needs to be incorporated into the improvement organization. We do not recommend incorporating marketing or R&D into the improvement organization, but projects and activities that are intended to drive top-line growth through innovation and new products and services should be managed within the improvement organization.

A Chief Improvement Officer (CIMO—CIO is already taken by Chief Information Officer; IM stands for Improvement), on the staff of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), should lead the improvement organization. Being on the CEO’s staff is critical because improvement work also is critical. In addition, this improvement work needs to be carefully coordinated with other functional groups, such as R&D, marketing, manufacturing, human resources (HR), and so on.

Furthermore, this coordination needs to start at the strategic level—that is, at the CEO staff level. The CIMO need not be the top technical person in the improvement group, just as the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) is not necessarily the top financial analyst. Instead, the position of CIMO requires significant vision and leadership skills, in addition to the ability to understand improvement. Several organizations, including GE and DuPont, have set a similar precedent by naming a senior Six Sigma executive who reported directly to the CEO.

The CIMO needs to have a proper leadership team, just as a CEO, CIO, or CFO needs a proper leadership team. Improvement is inherently a technical discipline, so the team needs strong technical expertise. It could be led by a Chief Master Black Belt (CMBB) or other appropriate title. This individual, with his or her own team, is then responsible for overseeing the training system and determining the proper mix of improvement methodologies to be included. Furthermore, this group determines which improvement method should be applied to each prioritized project. As discussed in previous chapters, holistic improvement does not mean that a given organization will utilize every improvement method in existence; instead, each organization needs to determine the best portfolio of methods for its own needs.

The CMBB cannot be expected to be an expert in all improvement methods within the portfolio. Therefore, he or she needs a critical mass of expertise for each methodology within the portfolio. Cross-training (that is, having individuals with expertise in multiple methods) is an obvious advantage. Furthermore, the CMBB needs to create a culture in which technical experts are open minded about improvement approaches instead of pushing each project toward the methods that they personally know best. Again, the culture needs to be one of starting with the problem and then objectively determining the best approach to solving it, not selecting favorite methods in advance.

It should be obvious that the improvement organization needs to maintain close connections with the other functional groups, including R&D, finance, marketing, HR, IT, and operations, whether the company’s operations are primarily manufacturing, banking services, hospital operations, or something else. These other functional groups no doubt will insist on having input on the decisions regarding the prioritization of improvement projects. Therefore, representatives from these groups should be regular participants at the CIMO’s staff meetings and at meetings to prioritize potential improvement projects. In this sense, the improvement organization should not have its own agenda, but should focus on the existing strategy and priorities of the company.

The proper size of the improvement organization obviously depends on the size of the company. However, keep in mind that this is the organization to maintain and improve the holistic improvement system over time, not to put it into place. That is, when the company moves from an initiative to a way of working, the level of resources needed should go down. Creating the system requires significant momentum and resourcing, which should be gradually reduced once the system is in place. As an analogy, constructing an office building requires a lot more resources than maintaining and improving it over time. Recall that the improvement organization is responsible for managing the overall improvement system, not for completing each project. All employees are expected to participate in improvement projects. Therefore, the responsibility for improvement is widely shared across the company.

Integration of Quality and Process Management Systems

Earlier chapters discussed launching a Lean Six Sigma initiative, with the intention of evolving this to a more holistic approach over time by gradually incorporating additional improvement methods. In Chapter 8, we discussed the need to expand the effort, including growing the top line by incorporating quality by design methods, such as Design for Six Sigma (DFSS). This can include other individual methods as well, such as the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ) and Quality Function Deployment (QFD). Quality and process management systems are often the last to be formally incorporated within the holistic improvement system. This is because many people do not think of quality or process management systems as “improvement” and because most companies already have a well-established quality organization.

The ISO 9000 quality system requires detailed documentation of process management and control procedures. Thus, the line between quality management and process management is often blurred. We therefore combine them into the “third leg” of the improvement stool, which we refer to as quality and process management systems. These systems include the set of procedures, methods, requirements, operating manuals, training, and so on that you use to manage a given work process. The work process itself can be an operational one, such as an assembly line, or a managerial one, such as the budgeting process. Every process has a process management system, although, in many cases, it is ad hoc, undocumented, inconsistent, and totally ineffective. Effective work processes almost always have a good process management system, which helps explain why the process is effective.

We take a strategic view of quality and process management systems, seeing them as an additional set of methods that can be used for improvement. For example, formally competing for the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA) or obtaining ISO 9000 certification can drive significant improvement. However, the investment required to do so is non-negligible. Therefore, we argue that the anticipated payoff from these investments needs to be compared with the anticipated payoff from other potential improvement efforts, such as quality by design or breakthrough improvement projects.

As discussed previously, we feel that this can best be accomplished by integrating the quality and process management organizations into the overall improvement organization. Fortunately, some natural synergies exist between major quality methodologies (particularly ISO 9000 and the Malcolm Baldrige Award), and quality by design and breakthrough improvement approaches (particularly Six Sigma). We highlight some of these natural synergies shortly.

Such synergies can produce a multiplicative rather than additive impact by implementing multiple projects in a coordinated fashion. This is why the project improvement portfolio is not simply a laundry list of projects, but should be actively managed to take advantage of such synergies. Furthermore, these synergies clarify why it is so important to house these quality initiatives within the improvement organization instead of having them sit outside as competitors to improvement.

Synergies with ISO 9000

ISO 9000 is widely used by diverse companies around the globe (ISO 9000 Standards, 2015). Many customers, particularly in the European Community, require ISO certification as a condition of doing business. Fortunately, many breakthrough improvement methods, such as Lean and Six Sigma, support ISO 9000 and help an organization satisfy the ISO 9000 requirements. In this sense, implementing Lean Six Sigma and implementing ISO are synergistic: The effort required to implement both is less than the sum of the efforts required for each individually. Furthermore, ISO 9000 is an excellent vehicle for documenting and maintaining the process management systems involving Lean, Six Sigma, and other breakthrough improvement methods. In other words, ISO 9000 can help make improvement the normal way you work.

ISO 9000 requires having a continuous improvement process in place (see Figure 9.1). However, ISO does not dictate what the process improvement system should look like. The holistic improvement system, including quality by design and breakthrough improvement methods, can provide the needed improvement process. ISO 9000-2015 requires that you measure (M), analyze (A), and improve (I). These are three phases of the Lean Six Sigma 2.0 DMAIC process improvement methodology. ISO 9000 also helps create the process mind-set that is required for holistic improvement to be successful.

Figure 9.1 ISO 9000 2015 model of a process-based quality management system

When expanded to working with suppliers, as we discussed in Chapter 8, holistic improvement also supports each of the ISO 9000 quality management principles:

1. Customer focus

2. Leadership

3. Engagement of people

4. Process approach

5. Improvement

6. Evidenced-based decision making

7. Relationship management

ISO 9000 can also provide valuable support to the holistic improvement system. ISO audits can be expanded to include monitoring the performance of processes improved via breakthrough improvement, or can be introduced through quality by design. Such monitoring should include the use of control plans developed for these improvement projects. In this manner, ISO 9000 becomes a key methodology to ensure that the overall holistic improvement system is maintained over time.

Synergies with the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award

The criteria used for selecting winners of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA) for performance excellence form a widely used tool for improving corporate performance. The Baldrige National Quality Program (2017) identifies outstanding companies in this area.

The Baldrige criteria have also been used in whole or in part to establish various state awards for performance excellence. The Baldrige criteria have seven categories of performance excellence:

1. Leadership

2. Strategy

3. Customers

4. Measurement, analysis, and knowledge management

5. Workforce

6. Operations

7. Results

Obviously, a holistic improvement system supports all the categories of the Baldrige criteria. In addition, the use of holistic improvement can significantly enhance the performance of the organization so that it better satisfies the Baldrige criteria. Conversely, as we explain shortly, pursuing the MBNQA often leads directly to identifying the most important improvement projects needed in holistic improvement. Again, there is a synergistic relationship between holistic improvement and the MBNQA.

Many companies use the Baldrige criteria to identify their best opportunities for improvement, even without formally applying for the award. Leadership typically charters a team to perform an organizational assessment; they identify, categorize, and prioritize the opportunities, and assign them to improvement teams for solution. These improvement teams generally have annual goals and report on progress monthly to leadership. Obviously, such project teams should be part of the overall improvement project portfolio. This project is intended to identify promising improvement projects that will subsequently also be part of the improvement project portfolio.

This approach can effectively turn the opportunities identified by the Baldrige assessment into projects that produce high-impact and lasting organizational improvements (Snee, 1999a). Baldrige assessments are typically done every 18 to 24 months because organizational change tends to occur slowly. When an organization uses such assessments, its outputs should be given high priority for selection into the project improvement portfolio.

A word of caution applies here: The most difficult aspect of using holistic improvement to capture the opportunities identified in a Baldrige assessment is properly defining the projects. The opportunities identified by the Baldrige criteria are frequently areas of opportunity that have a broad scope, making project definition challenging. A good approach is to perform an affinity analysis (Hoerl and Snee, 2012) to first group the areas of opportunity into logical categories and then put the resulting categories through the project prioritization process to identify good candidate improvement projects.

Synergies with Risk Management

Risk management in the form of risk identification and mitigation has become an increasingly important approach to process improvement and management. As we discussed in Chapter 1, “A New Improvement Paradigm Is Needed,” commercial organizations are faced with more significant risks than at any time in history. These include terrorism, litigation resulting from faulty products or processes, environmental disasters, computer hacking of confidential records, and allegations of social misconduct (sexual harassment, racial discrimination, utilization of overseas “sweat shops,” and so on). We consider risk management to be a key element within quality and process management systems, and we therefore feel it should be integrated into the improvement organization.

In Table 9.3, we show how holistic improvement methods and risk management are synergistic. A guiding principle is that risk increases as variation increases. This principle suggests that we should be looking for every opportunity to reduce variation. Statistical thinking and methods, in particular, are aimed at identifying, characterizing and reducing risk. ISO 9000 procedures also focus on minimizing variation in work processes.

NOTE

In Table 9.3, ISO has another standard, ISO 31000, that specifically focuses on risk management.

Table 9.3 Synergies of Holistic Improvement Methods and Risk Management

Holistic Improvement Method |

Risk Identification and Mitigation |

|

Innovation |

Creatively identifies unique approaches to reduce risk Creates robust products and processes |

|

Design for Six Sigma |

Uses formal improvement methods to take the unique approaches identified above from idea to actual deployment. Creates robust processes and products. |

|

TRIZ |

Identifies innovative problem-solving solutions for key risks. This holistic approach to problem-solving results in reduced risk. |

|

Six Sigma |

DMAIC addresses major sources of variation that increase risk. FMEA is used to identify how the process can fail. Processes are mistake-proofed. Standard operating procedures (SOPs) include use of checklists. Control plans and statistical process control methods are used to sustain improvements and reduce variation. |

|

Baldrige Assessment |

Enhances the Baldrige criteria categories for performance excellence: leadership, strategy, customers, measurement, analysis and knowledge management, workforce, operations, and results. These individually and collectively result in reduced risk Risk assessment is included in each of the Baldrige categories, enabling the identification of potential failures. |

|

Big Data Analytics |

Databases are designed to include data on all sources of variation and incorporate state-of-the-art security systems. |

|

Statistical Engineering |

Creates improvement project scope to ensure that all potential root causes are addressed by the project (big picture). |

|

ISO 9000 |

Involves ISO 9000 quality management principles: customer focus, leadership, people engagement, process approach, improvement, and evidenced-based decision making and relationship management. The individually and collectively result in reduced risk. The ISO companion standard, ISO 31000, focuses specifically on risk management. |

|

Total Productive Maintenance |

Uses predictive maintenance methods to reduce equipment failures and improve safety. Uses FMEA to identify how the process can fail. |

|

Lean |

Uses lean principles to optimize the flow of information and materials throughout the process ensuring customers receive the desired products, services, and information on time Uses FMEA to identify how the process can fail |

|

Kepner–Tregoe |

This problem-solving approach enables root cause analysis (RCA) on complex problems and enables the understanding and management of risks and opportunities |

|

Risk management can be incorporated into holistic improvement in two ways. First, and perhaps most obviously, the organization can make risk considerations part of the accepted use of each improvement method. This is accomplished in the following way:

![]() Ensuring that risk considerations, quantitative or qualitative, are identified during each improvement project.

Ensuring that risk considerations, quantitative or qualitative, are identified during each improvement project.

![]() Asking during each project, “How can this process fail?” In effect, this results in doing a formal or informal failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA). We know of a CEO who made FMEA an integral part of evaluating all strategic plans.

Asking during each project, “How can this process fail?” In effect, this results in doing a formal or informal failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA). We know of a CEO who made FMEA an integral part of evaluating all strategic plans.

Second, the company can incorporate risk management projects as candidates in the project improvement hopper, to be prioritized in conjunction with other candidate projects. These projects would specifically focus on identifying and managing risk, such as re-evaluating the organization’s computer security systems (perhaps by hiring professional “hackers” to try to break into the system) or determining the organization’s response system for a terroristic attack (perhaps from a disgruntled employee potentially bringing a gun on the premises to seek revenge for perceived mistreatment). Most universities and high schools now have formal plans for addressing active shooters on campus, for obvious reasons.

At first glance, it might seem that such risk management projects are too important to be jointly prioritized along with process improvement projects. This is our point, however. All projects should compete for selection and resourcing on an equal playing field, without organizational boundaries or politics influencing the process. We argue that such critical risk management projects will swiftly rise to the top of prioritization if there is an equal playing field. However, if risk management is a separate organization, there is a distinct possibility that it will not receive the funding it needs to be effective, while perhaps other improvement groups remain overfunded.

Don’t Forget About Process Control

Quality and process management is obviously a broad category, as we have shown. A key element of this category, and one that we have not addressed in detail up to this point, is process control. Process control makes adjustments to the process, often in real time, to maintain the performance level. It can be accomplished manually, by human intervention, or through automated control systems. Process control addresses problems that have caused deterioration in performance and returns the process to standard conditions.

Process control is often confused with process (breakthrough) improvement, which makes fundamental changes to the process itself or the way it is operated, to achieve higher levels of performance than have been achieved in the past. For example, most Six Sigma projects focus on process improvement instead of process control.

It should be clear from these definitions that excellence in process control does not, in itself, produce breakthrough improvement. However, poor process control inevitably produces a sequence of crises and unexpected problems. This results in constant firefighting, which pushes true improvement to the back burner. Process improvement works best on a solid platform of good process control, which is also required to sustain the gains of the improvement projects over time. Therefore, a holistic improvement system needs a balance of process improvement and process control, as well as new product and process innovation (quality by design).

We have already mentioned a number of tools that are often included in Six Sigma or other types of projects for use in process control. Control charts and mistake proofing are two examples. Furthermore, having employees who are trained in formal approaches to routine problem solving (using methods such as Kepner–Tregoe, for example) is helpful in ensuring good process control. When employees can handle routine problems as they occur, these routine problems don’t become serious problems.

A few guiding principles for process control are helpful:

![]() Focus control efforts on key processes.

Focus control efforts on key processes.

![]() Ensure that these key processes produce the right data to allow effective monitoring and control.

Ensure that these key processes produce the right data to allow effective monitoring and control.

![]() Obtaining the right data might require putting new measurement systems into place.

Obtaining the right data might require putting new measurement systems into place.

![]() Have people at various levels in the organization routinely analyze process data using relevant tools and take appropriate actions; improvement is everyone’s responsibility.

Have people at various levels in the organization routinely analyze process data using relevant tools and take appropriate actions; improvement is everyone’s responsibility.

![]() Often the people who work within the process understand the data best, not necessarily Black Belts or other technical resources.

Often the people who work within the process understand the data best, not necessarily Black Belts or other technical resources.

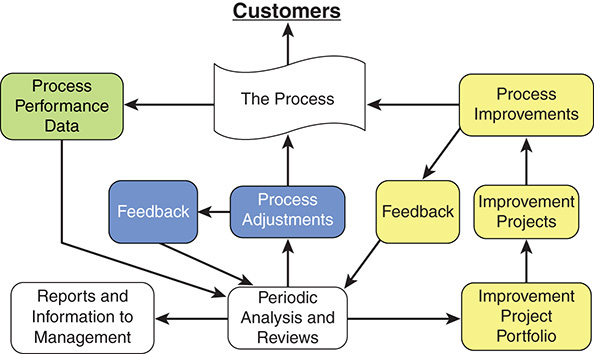

Figure 9.2 (Snee, 1999b) depicts a high-level schematic of how routine data can be utilized for process improvement and control. The organization should collect data from the process on a routine basis. Various levels of management should review this data on a regular basis to decide what, if any, process actions should be taken. Typical review groups for high-throughput environments (manufacturing, billing, hospitals, logistics, and so on) are as follows:

Review Team |

Review Timing |

Process operators |

Continuously and daily |

Process managers and staff |

Weekly |

Site manager and staff |

Monthly |

Business manager and staff |

Quarterly |

Figure 9.2 Schematic of data-based process improvement and control system

Process operators can be assembly line workers, accountants, nurses changing over beds in a hospital, or salespeople. Each should review the process performance data continuously, to look for out-of-control situations, and should review daily summaries to detect other sources of problems. Analysis tools such as run or control charts and Pareto charts are often used here.

We noted in Chapter 7 that management review is a critical success factor for holistic improvement. Regular management review keeps the effort focused and on track. We know of no successful holistic improvement deployment, or even Lean Six Sigma implementation, in which management reviews were not a key part of the deployment process. We refer to management reviews as the “secret sauce”: Done regularly and at numerous levels, they significantly enhance the probability of success. Regular reviews not only ensure the success of a particular effort at a particular point in time, but they also help sustain the effort over time.

The process control plan, developed in the Control phase of the DMAIC framework of an improvement project, documents for the operators what to look for, what actions to take, and whom to inform when additional assistance is needed. The control plan typically details the process adjustments needed to bring the outputs back to the desired target and range. Typical control tools that the operators use for troubleshooting include process maps, control charts, histograms, and Pareto charts. We discuss the proper role of the methods and tools in more detail in Chapter 10, “Final Thoughts for Leaders.”

As depicted in Figure 9.2, there is a short feedback loop between analyzing process data and making adjustments. This inner loop is intended to represent process control efforts, including routine problem solving. This activity should occur in near real time and not be based on a formal project. Examples of such process adjustments are changing the pressure setting on a piece of stamping equipment to eliminate bad stamps, calling in additional accountants to close the books on time, and having a salesperson work overtime to meet a sales quota. However, such efforts are primarily aimed at sustaining current performance levels, not improving to new levels.

Improving to new performance levels often requires involving additional people with specialized skills, such as engineers in manufacturing or experienced underwriters in insurance. True improvement is usually achieved through project teams that include process operators, technical specialists, and perhaps someone trained in the improvement methodologies we have discussed.

The improvement project feedback loop is an outer loop in Figure 9.2, in that it requires more time and is utilized only when routine problem solving will not solve the problem. Occasionally, the team determines that breakthrough improvement is not sufficient and that a fundamentally new process needs to be designed (for example, automating a manual billing process). In such cases, a quality by design project, perhaps using DFSS, needs to be chartered. Note that all of this activity is part of the holistic improvement system, so there are no organizational boundaries between process control efforts, improvement efforts, and innovation efforts, as is often the case in traditional organizations.

As we have seen, process control and routine problem solving activities should occur in real time—they generally don’t require a formal project. However, process control still fits within a holistic improvement system, for three main reasons. First, the improvement organization should oversee the use of process control and problem-solving tools. That is, the improvement organization is responsible for determining the best set of tools that should be utilized and for ensuring that a training system is in place to develop the needed skills in these tools. Second, formal projects are needed to initially put these control systems into place. For example, if an organization decides to utilize control charts for process control, the employees will need training in control charts and some help in deploying them in the workplace. This will require a project.

Third, recurring process control issues often indicate that the process control system is not working properly and needs to be upgraded. This typically requires a breakthrough improvement project, to put in place a more effective control system. Although the project focuses on process control, not improvement, fundamentally upgrading the process control system should produce true improvement: levels of performance not previously seen. Therefore, we consider this a breakthrough improvement project.

Don’t Forget About Managerial Processes

For true holistic improvement, process management and control systems must be developed for managerial processes. These can include budgeting, planning, employee selection, training and development, financial reporting, project management, performance management, communication, and recognition and rewards. Chapter 7 defined managerial systems and processes and discussed them in more detail.

The approach for developing control systems for managerial processes is essentially the same as for operational processes: integrating holistic improvement concepts, methods, and tools with the process management systems for these managerial processes. The key steps follow:

1. Recognize that all work (even managerial work) occurs through processes.

2. Identify a key managerial process.

3. Select a set of performance measurements.

4. Collect data on the process and review it at appropriate levels of management, as discussed previously.

5. Take action to make process adjustments.

6. Make fundamental improvements to the process by defining and completing improvement projects as needed.

In the ongoing effort to collect the process data, analyze the data, and take action based on this data (as well as subsequent improvement projects), holistic improvement concepts, methods, and tools become part of your daily work. Process management and control might not be the sexiest aspect of a holistic improvement system, but it is most critical in terms of making improvement a normal part of everyone’s job. This is because it defines the routine procedures that the organization will use in its daily work. Therefore, if holistic improvement concepts, methods, and tools are embedded into process management and control systems, holistic improvement will become the way we work, both in operations and in management.

Admittedly, unique challenges arise in deploying process management systems for managerial processes. Perhaps the most challenging aspect is selecting the right process metrics. As we noted in Chapter 6, “Launching the Initiative,” the key metrics for nonmanufacturing processes are typically accuracy (correctness, completeness, errors, defects, and so on), cycle time, cost, and customer satisfaction. However, many managerial processes do not have existing measurement systems that provide useful data for improvement. For example, few companies measure and analyze metrics on the effectiveness of their budgeting processes. Table 9.4 shows an example set of metrics used to measure the performance of a Lean Six Sigma training process (Snee, 2001). As in any important work activity, leadership (including regular reviews by various levels of management) is the key success factor.

Table 9.4 Lean Six Sigma Training Metrics

Participants like the training experience |

|

Participants learn the methodology |

|

Participants use the methodology |

|

Participants get results |

|

Another challenge in many managerial processes is that the data is often sparse. One company wanted to improve its annual college campus recruiting process. However, once a Green Belt got into the project she realized that the most important data for improvement purposes was generated only once a year, after each wave of campus recruiting.

A less obvious challenge is resistance to the introduction of process management and control systems for managerial processes because some people view them as threatening. As noted in Chapter 7, when we introduce formal metrics and reviews to manage these processes, the process owners, such as human resources (HR), finance, information technology (IT), and so on, might feel that Big Brother is watching them or that they will be micromanaged. As long as the emphasis remains on improving the process and not on assigning blame, this concern will be quickly seen as groundless.

Motorola Financial Audit Case

Stoner and Werner (1994) present an example of using Lean Six Sigma in the management and control systems for of a managerial process: Motorola’s internal financial audit process. The first step, and a major breakthrough in thinking, was to view each internal audit not as an event, but as a process with five key steps:

1. Schedule the audit.

2. Plan the audit.

3. Perform the audit.

4. Report the results.

5. Perform the post-audit check.

Motorola developed performance measurements for the process, including internal errors, cycle time required to complete the audit, customer feedback on the audit, and cost in terms of person-hours to do the audit. Additional audit process measures included the time and cost for the audit of the corporate books by an external auditor. Accuracy of the external audit was the responsibility of the external auditor. To maintain independence, Motorola could not be involved in evaluating accuracy.

Impressive results were obtained through this approach. The process measures led to several breakthrough improvement projects in internal auditing. Within three years, Motorola reduced internal errors from 10,000 ppm to 20 ppm (parts, or errors, per million opportunities). The company reduced its report cycle time from 51 days to 5 days. The quality of the customer feedback report was 21 times better in two years. Audit person-hours dropped from 24,000 hours to 12,000 hours, while annual sales increased from $4.8 billion to $11.3 billion during the same time period.

Clearly, higher-quality work was being done in less time and at less cost. Additionally, the external audit cycle time dropped by 50 percent because of better internal audit information from the process management system, producing $1.8 million cost avoidance per year. Unfortunately, many companies cannot achieve this same level of improvement because they still view internal auditing as an event instead of a process that can be managed and improved.

Accounting scandals at major corporations such as Enron, WorldCom, and Arthur Anderson have only reinforced the need for rigorous process management and control systems in finance in general and auditing in particular. Such systems could be considered part of the organization’s risk management system.

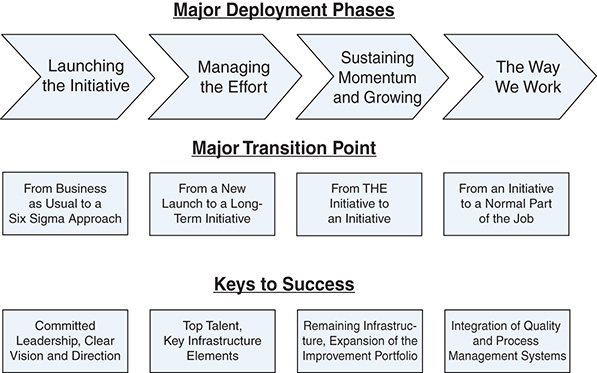

The Long-Term Impact of Holistic Improvement

Chapter 5, “How to Successfully Implement Lean Six Sigma 2.0,” presented the typical deployment phases of Lean Six Sigma 2.0, as shown in Figure 9.3, from initial deployment to expansion to holistic improvement. The first major transition is from business as usual to a Six Sigma approach. Most organizations launch Six Sigma or perhaps Lean Six Sigma in operations. Shortly thereafter, it becomes important to formally manage the initiative. This requires involving top talent and creating a formal infrastructure. Next, the organization typically expands the areas of application and the improvement portfolio in the third phase, sustaining momentum and growing the effort. New product development and other quality by design methods should also be integrated into the initiative at this point.

Figure 9.3 Roadmap for Lean Six Sigma 2.0 deployment

However, to achieve Lean Six Sigma 2.0, true holistic improvement, the organization still needs to make a major leap. This involves creating an overall organizational improvement system, incorporating multiple improvement methodologies, and integrating them within one improvement organization, as discussed earlier. Integrating quality and process management systems into this overall improvement system is typically the last major transition. Once this has been successfully accomplished, the organization has made improvement the way it works.

Top management has fueled the deployment through its leadership, evidenced by such things as clear goals, resources, breakthrough expectations, and a deployment plan. Of particular importance is the clear communication of very high expectations—what we need to do to be successful, how we are going to do it, and what will happen when we are successful. Without these expectations the organization will remain confused about what is expected and what will happen. Results rarely exceed leadership expectations. Let’s take a closer look at this gradual evolution of the Lean Six Sigma initiative as it progresses to holistic improvement, or Lean Six Sigma 2.0.

The work done in the first 12 to 18 months, in the early phases of deployment, typically produces many useful results, including some worthwhile byproducts. Most important are business results in the form of improvement to the bottom line and increased customer satisfaction. This helps Lean Six Sigma build credibility, pay for itself, and provide fuel for continued growth. The capability of the organization is thereby greatly increased, including enhanced teamwork and cross-functional cooperation. Most important, the organization begins to believe that Lean Six Sigma will work here and that each person can personally benefit from Lean Six Sigma.

At about the 18-month time point, toward the end of the second phase of deployment, a move toward holistic improvement should be underway or at least initiated. Important considerations to include follow:

![]() Work to involve all aspects and functions on the organization including operations, R&D, finance, and sales and marketing.

Work to involve all aspects and functions on the organization including operations, R&D, finance, and sales and marketing.

![]() Address all aspects of organizational performance: flow of materials and information, product quality, and customer satisfaction.

Address all aspects of organizational performance: flow of materials and information, product quality, and customer satisfaction.

![]() Put management systems in place to guide and sustain the improvement initiative over time.

Put management systems in place to guide and sustain the improvement initiative over time.

![]() Integrate systems for quality by design, breakthrough improvement, and quality and process management.

Integrate systems for quality by design, breakthrough improvement, and quality and process management.

![]() Use a more diverse portfolio of improvement methodologies, each chosen to fit the needs of particular projects.

Use a more diverse portfolio of improvement methodologies, each chosen to fit the needs of particular projects.

![]() Use improvement as a leadership development tool.

Use improvement as a leadership development tool.

When Lean Six Sigma deployment is off and functioning, the evolution toward holistic improvement should be initiated, evolved, and nurtured.

Two to three years into the initiative, typically during the phase of sustaining momentum and growing, the longer-term benefits begin to appear. The leadership team bench strength begins to increase as the Lean Six Sigma experience provides the organization with a larger number of highly skilled leaders. Organizations typically see greater use of scientific thinking in how they manage, including focusing on processes, using data to guide decisions, and understanding the effects of variation on the decision making process. The transition to one improvement organization becomes a more natural process.

Holistic Improvement Drives Culture Change

The financial benefits from holistic improvement are certainly welcome, but these will dry up gradually if the organization does not maintain a focus on improvement as a cultural value. This is analogous to someone who goes on a strict diet as a New Year’s resolution and loses 30 pounds. If that individual declares success and gradually returns to his or her normal lifestyle and eating habits, the pounds will return. Only if the person makes a permanent change in lifestyle will the pounds stay off. Nutritionists and personal trainers generally agree that no one else can force or pressure you to keep weight off; it has to be something that you believe in and commit to for the long term. In other words, it must become part of who you are—your culture.

Similarly, we argue that if holistic improvement is truly going to become how you work, it must become part of your culture. Culture change cannot be implemented by edict or driven from PowerPoint charts; it must be led (including through leading by example). Fortunately, when organizations make the changes noted in this book (especially the ones in this chapter, such as integrating holistic improvement concepts, methods, and tools into quality and process management systems), the culture naturally changes. Improvement becomes integral to how we work on a day-to-day basis.

Consider an illustration of this new type of thinking. Jack Welch, former CEO of GE, wrote a discussion of the impact of statistical variation on customer satisfaction in the 1998 GE Annual Report. This prompted people to begin working in a new way, and a new culture began to emerge. This solid foundation enhances the organization’s ability to expand and grow. The cadre of MBBs, Black Belts, and other experienced improvement leaders that has emerged, along with a focus on improving all processes, creates a better climate for rapid assimilation of new acquisitions. This climate also makes it possible to move acquired processes to new locations and get them productive in record time.

The following list summarizes some of the cultural changes seen in the organization along the way.

![]() Improvement is seen as a normal part of the job for everyone; improvement is not a special initiative.

Improvement is seen as a normal part of the job for everyone; improvement is not a special initiative.

![]() Leadership understands that financial and other desired results are produced by effective and efficient processes: The process produces the results.

Leadership understands that financial and other desired results are produced by effective and efficient processes: The process produces the results.

![]() Improvement methodologies are seen as the how, not the what. Neither leadership nor rank-and-file employees fall in love with specific methodologies.

Improvement methodologies are seen as the how, not the what. Neither leadership nor rank-and-file employees fall in love with specific methodologies.

![]() The organization never declares success; everyone understands that improvement is a permanent commitment.

The organization never declares success; everyone understands that improvement is a permanent commitment.

![]() Decision making at all levels is guided by data whenever possible: “In God we trust—all others, bring data.”

Decision making at all levels is guided by data whenever possible: “In God we trust—all others, bring data.”

![]() Data has intrinsic value; database systems are viewed as gold mines instead of nuisances to be avoided.

Data has intrinsic value; database systems are viewed as gold mines instead of nuisances to be avoided.

![]() Hiring processes search for people who will be successful in the new culture; no employee, no matter how talented, is more important than the organization.

Hiring processes search for people who will be successful in the new culture; no employee, no matter how talented, is more important than the organization.

![]() Because of ongoing opportunities to improve their workplace, employees feel empowered, respected, and energized; there is no we and they.

Because of ongoing opportunities to improve their workplace, employees feel empowered, respected, and energized; there is no we and they.

People begin to believe that a focus on process improvement is the way to improve business performance and growth. They see that this improvement comes not simply by demanding it, but by having methods and tools available to improve the processes that generate the results. Their focus remains on improvement itself, not on individual methods or tools. They realize that just as making weight loss permanent requires a fundamental change in lifestyle, organizational excellence requires a permanent commitment to improvement.

Process improvement rises to a new and higher level of importance, a part of how you run the business. Using data and facts as a guide to decision making becomes the norm. “Please show me the data that led to this recommendation” is a common request when evaluating proposals and recommendations. Instead of avoiding clunky, antiquated databases, employees have modern and agile data systems that they view as opportunities waiting to be mined. A new way of working evolves and higher levels of performance results are expected and achieved. Recruiting efforts take culture seriously, realizing that some interviewing candidates, potentially some with outstanding credentials, might not want to work in such a collaborative environment. As the president of a Silicon Valley tech company is rumored to have said, “I don’t hire jerks, no matter how smart they are.” (We substituted the word jerks here for his more vulgar term.)

Improvement As a Leadership Development Tool

Holistic improvement has another positive side effect that warrants further discussion: leadership development. This has obvious connections with making holistic improvement the way we work. Jack Welch (2005) reminds us, “Perhaps the biggest but most unheralded benefit of Six Sigma is its capacity to develop leaders.” Companies such as Honeywell, GE, DuPont, 3M, and American Standard require managers to achieve Lean Six Sigma Green Belt certification and, in some instances, Black Belt certification for management promotion.

Welch (2001) further states:

We’ve always had great functional training programs over the years, particularly in finance. But the diversity of the company has made it difficult to have a universal training program. Six Sigma gives us just the tool we need for generic management training since it applies as much in a customer service center as it does in a manufacturing environment.

Why is leadership development so important to make holistic improvement the way we work? The answer is straightforward: Today’s talent will likely become tomorrow’s leaders, and we need to ensure that these leaders fully understand and embrace holistic improvement. Having ex–Black Belts and Master Black Belts (MBBs) in senior leadership positions ensures that the culture change is permanent, which is a major element of making the transition from an initiative to the way we work.

One of the most important leadership skills that can be developed through holistic improvement is to help an organization move from one paradigm of working to another paradigm—this is cultural change. Changing how we work means changing our processes. Holistic improvement provides the concepts, methods, and tools for improving processes. Thus, holistic improvement gives leaders the strategy, methods, and tools to change their organizations. This is a key leadership skill that has been missing from most organization’s approaches to leadership development. Such change-management skills will likely be critical in addressing future organizational change. As we discussed in Chapter 1, the world is changing rapidly, and the ability to learn and change rapidly is virtually the only lasting competitive advantage.

Some other leadership skills also can be developed through holistic improvement:

![]() Linking improvement needs to business strategy and goals

Linking improvement needs to business strategy and goals

![]() Leading a team effectively

Leading a team effectively

![]() Identifying opportunities for improvement

Identifying opportunities for improvement

![]() Matching improvement methodologies to specific problems

Matching improvement methodologies to specific problems

![]() Delivering bottom-line results consistently

Delivering bottom-line results consistently

![]() Using data to guide decision making

Using data to guide decision making

![]() Using DMAIC as a general-purpose problem solving model

Using DMAIC as a general-purpose problem solving model

Summary and Looking Forward

Deploying Lean Six Sigma is a major organizational initiative that requires a lot of effort and resources. To expand to true holistic improvement (Lean Six Sigma 2.0), maintain the gains over the long term, and continuously improve, organizations need to integrate holistic improvement into the way they work. In other words, they need to institutionalize it. In this way, they can retain the benefits without retaining a separate infrastructure permanently.

Of course, without integrating holistic improvement into the way you work, the benefits will disappear with the separate infrastructure, and holistic improvement will have been just another fad that offered temporary benefits. As the old saying goes, “It’s easy to quit smoking. I’ve done it dozens of times.” Successfully transitioning is therefore the key to making the financial and organizational benefits permanent.

In this chapter we discussed ways of making the transition and integrating holistic improvement into the way we work. The three main approaches were: (1) creating and managing an overall improvement system that guides and integrates all three types of organizational improvement; (2) integrating holistic improvement concepts, methods, and tools with your quality and process management systems; and (3) changing the culture by utilizing holistic improvement as a leadership development tool.

Quality and process management systems, including process control systems, are extremely important and valuable with or without holistic improvement. They are particularly critical when transitioning from an improvement initiative to the way you work because they replace much of the holistic improvement infrastructure while maintaining the gains. If holistic improvement is embedded within the quality and process management systems, it becomes the normal way work gets done. One key aspect of any quality and process management system is the process control system, which often triggers the creation of improvement projects within the holistic improvement system.

The important role of leadership continues and becomes even more important—and, of course, leadership never ends. In our view, organizations that publically declare success with Lean Six Sigma or other improvement initiatives and then move on to something else have dropped the ball and walked away from future benefits. In the next chapter, we provide some thoughts for leaders that will enhance their abilities to provide effective leadership of holistic improvement into the future.

References

Baldrige National Quality Program. (2017) Criteria for Performance Excellence. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute for Standards and Technology.

Hoerl, R. W., and R. D. Snee. (2012) Statistical Thinking: Improving Business Performance. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Snee, R. D. (1999a) “The Impact of Six Sigma: Today and in the Future,” Presented at the Quality and Productivity Research Conference Sponsored by the American Statistical Association and American Society for Quality, General Electric Corporate R & D Center, Schenectady, NY, May 19–21, 1999.

Snee, R. D. (1999b) “Statisticians Must Develop Data-Based Management and Improvement Systems As Well As Create Measurement Systems.” International Statistical Review Vol 67, No 2: 139–144.

Snee, R. D. (2001) “Make the View Worth the Climb: Focus Training on Getting Better Business Results.” Quality Progress. (November): 58–61.

Stoner, J. A. F., and F. M. Werner. (1994) Managing Finance for Quality. Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Quality Press.

Welch, J. F. (2001) Jack: Straight from the Gut. New York: Warner Business Books.

Welch, J. F. (2005) Winning. New York: Harper Collins.