4 Training The essential ingredient

‘Training is a continuing investment in the most valuable of all our national resources — the energies of our people’1 and many consider it, along with education, to be imperative to the industrial success of the UK. This chapter examines training from a number of different perspectives. First, it attempts to place the importance of training into a broader national context and to highlight its benefits to both organisations and individuals. It goes on to use a training framework to explore how organisations can systematically train their employees.

4.1 Training: the broader national perspective

The relationship between training, education and industry is one which has generated a great deal of debate and controversy. The idea that there is a relationship between education, training and industrial performance is not a new one: Baron Lyon Playfair (1851, 1870) drew attention to the comparative weakness in his reports on technical education, and by 1903, Marshall noted the insecurity of Britain’s position. In 1964, the Industrial Training Act was introduced and the Industry Training Boards were created. Further legislation in 1973 set up the Manpower Services Commission, one of whose aims was to develop human resources ‘to contribute fully to economic well being’. The MSC (later known as the Training Commission and the Training Agency) scored initial successes in improving industrial training in the UK, however, the underlying problems still remained. Education and training were once seen as vehicles for improving and enhancing organisations as well as society at large. Today, they are frequently regarded as an expensive commodity whose worth is often linked with the lack of the UK’s industrial performance.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the debate about education and training in Britain was related to the perceived need to enhance the nation’s economic competitiveness which, it was felt, had long been neglected.2 ‘We in Britain have over the years consistently under-invested in human capital3 and ‘we have not sufficiently recognised its [training] importance in the past. This we must remedy and ensure that the skills of our people are fitted for the challenge of the years ahead’.4

The contribution of education and training to Britain’s competitiveness has been accepted by both ministers and industrialists, and this has given the debate a new impetus. Britain’s poor economic performance is now firmly blamed on ‘low investment’ in education and training. There is a consensus in the growing body of competitive education and training research that Britain provides significantly poorer education and training for its workforce than its major international competitors.5

The combination of poor performance during compulsory schooling years and a high percentage of students leaving school at 16 has meant that the average British worker enters employment with relatively few qualifications. This lack of initial qualifications does not seem to be compensated by increased employer-based training. Indeed, quite the reverse seems to be true; British firms offer a lower quality and quantity of training than those of its major competitors. The ‘Training in Britain Survey’ (1989) found that of those employers that did train (1 in 5 didn’t), no more than 48 per cent of the workforce was covered. In other words, more than half the workforce did not benefit from any form of training. By 1995 of the 22 million employees in the UK about 1 in 4 received job-related training. Of those employees receiving no training, approximately 47 per cent reported that they had never been offered training by their current employer on or away from the job. This group represents 1 in 3 (34 per cent) of all employees. France and Germany have already achieved the equivalent of our (old) Lifetime Target 3 (50 per cent of the workforce qualified to at least NVQ 3 or equivalent) and are aiming for 80 per cent by the year 2000. Japan achieved this in 1986. Although it is difficult to prove a direct empirical relationship between education and training and economic performance, no-one would dispute that a qualified engineer is more likely to produce a complex piece of equipment than an unskilled employee. However, do marginal differences in the quantity and quality of education and training affect performance?

There are those who would argue that the expansion of British industry has been hindered by the failure of the education and training system to produce sufficient quantities of skilled labour (producing skills shortages). Furthermore, the ability of the British economy and organisations to adapt to longer-term shifts in international competition has been impeded by the lack of qualified personnel.

The notion of ‘skills shortages’ is not a new phenomenon. In 1968, the Donovan Commission held that ‘the lack of skilled labour has constantly applied a brake to our economic expansion since the war’.6 ‘This view was held throughout the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. A series of studies in the 1980s demonstrated the strong positive correlation between industrial productivity and skills levels.7 So why has Britain failed to train?

It is true that there was a gradual expansion of educational provision during the post-war period, but this was not reflected in training provision, due largely to the fact that training was left in the hands of industry.

4.2 Training and industry

Why did industry and organisations fail to rise to the training challenge? One explanation is that organisations consider it cheaper for them to hire already skilled workers than to train their own and risk them being poached by other companies — this is likely to be the major reason for under-investment in training.

A major study undertaken in the mid-1980s revealed that there were additional reasons why employers did not train as extensively as their international counterparts.8 Few employers felt that training was sufficiently central to their business for it to be a main component in their strategy. The majority of employers believed that the amount of training they did was about right. Training was rarely seen as an investment, there seemed to be little analysis of training needs or any subsequent evaluation of the little training that did take place. Training was not seen as a major contributor to competitiveness. The reluctance to invest in training was put down to uncertain future markets, technological developments, poaching and demarcation.

There were few external pressures for organisations to invest in training (for example, from competitors, employees, unions, external commentators, government). In Germany, by contrast, there is a strong formalised tradition of training backed by legislation monitored for content and with recognised qualifications. Likewise in France, legislation stipulates a minimum expenditure on training that each organisation must undertake, together with statutory rights for individuals to training leave. In the USA, training is less formalised — the pressure comes from individuals. Nevertheless, the recent Presidential Commission on Skills has given renewed impetus to training in core skills. The driving force for training in these countries is either strong cultural pressure or a clear legislative structure. The conclusion to be drawn from this evidence is that if Britain’s performance on training is to improve, this can only be achieved by a major change in employer and employee attitudes to training: ‘To compete internationally the UK needs a highly motivated and well qualified workforce. We need … employers who see the importance of developing the skills of their employees, and people in the labour force who take their development seriously.’9

4.3 Making the case for training: benefits for the employer and the individual

Effective training is said to contribute significantly to the improvement of competitiveness, productivity and the quality of services to customers.10 The tangible benefits of training to employers are numerous. A recent survey11 identified the following: training costs less in the long run than recruiting fully trained workers. Evidence suggests that ‘recruited fully trained workers’ tend to leave much sooner than employees the organisations had trained themselves. Training also imparts the ‘right attitude’ to employees and ‘attitudes’ are often just as important as skill and knowledge acquisition. The long-term benefits of training outweigh the short-term costs. For example, higher skill and knowledge levels, lower labour turnover, reduced recruitment costs and a greater commitment to the organisation. Improved efficiency results from savings from material costs due to reduced wastage; improved delivery performance; improved quality, reliability and range of products or services to customers; more efficient scheduling of work and improved responsiveness to specific customer requirements; a more flexible and adaptable workforce generally, with faster adaptation to new technologies in particular.12

Given the breadth of these benefits, it is hard to understand why so many organisations fail to train their employees systematically. While most employers would agree that training is ‘a good thing’, there are some factors which deter them from investing in training. These include the perceived costs of training and a real concern about employees leaving once trained.

Many individuals consider training an important aspect of their working lives. Economic and other reasons are often given for wishing to undertake training. A survey carried out in 1994 of individuals’ attitudes to learning13 found that over two-thirds of respondents thought people given training find their jobs more interesting. More than half thought that those who received training at work got promotion or better pay, and over three-quarters felt that they were more marketable and employable as a result of training. Furthermore, the Employment in Britain Survey14 found that training provision was near the top of people’s preferences about what a job should offer.

Since training provides so many benefits to both employers and employees, there is a clear need for organisations to invest in training, to harness the interests of individuals, as well as improve the operation of the training market making it easier for them to define and obtain from internal and external providers the training they require.

Thus far, ‘training’ has been referred to as a generic term but it can take a multitude of guises. Let us consider the term ‘training’ in more depth.

4.4 Towards a definition of training

Training is a subject which everyone knows something about, but it still poses problems when one attempts to provide a hard-and-fast definition. Numerous definitions of training have appeared over the years. For example, in the 1970s training was considered to be: ‘the systematic development of the attitude, knowledge and skill behaviour pattern required by an individual in order to perform adequately a given task or job’15 or ‘a sequence of experiences or opportunities designed to modify behaviour in order to attain a stated objective’16 or ‘any activity which deliberately attempts to improve a person’s skill at a task’.17

By 1981, there was already a change in emphasis:

a planned process to modify attitude, knowledge or skill behaviour through learning experience to achieve effective performance in an activity or range of activities. Its purpose in the work situation is to develop the abilities of the individual and to satisfy the current and future manpower needs of the organisation.18

a planned effort by an organisation to facilitate the learning of job-related behaviour on the part of its employees.19

the systematic acquisition of skills, rules, concepts or attitudes that result in improved performance in another environment.20

Ultimately, training includes all forms of planned learning experiences and activities whose purpose is to effect changes in performance and other behaviour through the acquisition of new knowledge, skills, beliefs, values and attitudes. Defined in this way, training reflects activities that are intended to influence the ability and motivation of individual employees. In other words, training can prepare people to work and help increase their worth to their employer and to themselves.21

While most training would fall into the broad statement above, it can include a range of activities. These include:

• Traditional training: training given to promote the learning of specific, factual and narrow range of content to facilitate or improve human performance on the job, for example, technical skills training.22

• Education: learning experiences that improve overall competence in a specific direction.23 This is typically associated with secondary and higher education in particular fields of study.

• Vocational education: a set of learning experiences that are broader in scope than training but narrower than general education, for example, apprenticeship training.

• Management development: organisationally provided educational activities focused on improving managerial performance through training in technical, human relations and organisational decision-making skills.24

• Organisational development: organisationally provided educational activities focused on changing employees’ beliefs, values, attitudes and behaviour that hinder human interactions and thus human problem solving and decision-making in various departments, divisions or the total organisation.25

Common to all these activities is the underlying assumption that organisations and the people within them develop by learning irrespective of the approach adopted. A further basic principle is that for training to be worthwhile, it is imperative that learning takes place.

4.5 Training and learning

‘Learning is a relatively permanent change in behaviour that occurs as a result of practice or experience.’26 Therefore, we can say that the learning experience goes to the heart of all training activities, and that training, if it is to be successful, depends on an understanding of the learning process.

The trainee will bring to any learning situation a range of knowledge, skills and attitudes previously acquired. The trainer must build on these attributes, which will vary from person to person, so that each trainee can gain new knowledge, skills and attitudes. However, no two trainees will necessarily learn in the same way. In practice, the trainer will try to provide a learning situation that appears to meet the needs of the greatest number of trainees. Trainees may also vary in the degree of motivation they possess and in their level of self-esteem. Those with low motivation/self-esteem will normally take longer to complete a training programme than the well-motivated trainee.

Learning theories can be complex and diverse with distinct paradigms. Common themes shared by most learning theorists are that motivation goes to the core of learning be it extrinsic motivation or intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation refers to factors ‘extrinsic’ to the job itself, but whose absence leads to job dissatisfaction, e.g. company policy, supervision, working conditions, pay, interpersonal relations, etc., sometimes known as hygiene factors. Intrinsic motivation refers to factors ‘intrinsic’ to the job itself which are strong determinants of job satisfaction, e.g. achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility and advancement.27 Ultimately, whatever the source of motivation, the individual needs to be convinced of the need for training, for without such commitment, learning will be at best a very slow process. Other individual differences such as personality, intellectual ability, age, and the learning environment also affect individual learning and the rate at which people learn.

Kolb and the learning process

People learn in different ways. People have styles of learning which influence not only how they learn in a particular situation but also how they manage, solve problems, and make decisions in their work. However, several attempts have been made to extract a general model of the learning process from the apparent diversity of learner behaviour. According to Kolb (1974),28 learning is viewed as a circular and perpetual process, whose key stages are experience, observation of and reflection on experience, analysis of the key learning points arising from experience, and the consequent planning and trying out of new or changed behaviour (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 The learning process

Source: Kolb, Rubin, Mclntyre, Organisational psychology

Honey and Mumford29 refined Kolb’s categories and used them in selecting the type of trainee (identified by learning style) most likely to benefit from a certain type of programme. They found that people’s predominant learning styles tended to fall into one of the following four categories: activists, reflectors, theorists, pragmatists. These relate to the four different learning processes described by Kolb in 1974.

Activists involve themselves fully in new experiences. They enjoy the here and now and are happy to be dominated by immediate experiences. They are open minded, not sceptical and this tends to make them enthusiastic about anything new. They revel in short-term crisis fire fighting. They often tackle problems by brainstorming. They tend to be bored with implementation and longer-term consolidation.

Reflectors collect and analyse data about experiences and events, so they tend to postpone reaching definitive conclusions for as long as possible. They prefer to take a back seat in meetings and enjoy observing other people in action. When they act, it is as part of a wide picture which includes the past as well as the present, and others’ observations as well as their own.

Theorists tend to be detached, analytical and dedicated to rational objectivity rather than anything subjective or ambiguous. Their approach to problems is consistently logical. They prefer to maximise certainty and feel uncomfortable with subjective judgements, lateral thinking and anything flippant.

Pragmatists are keen on trying out ideas, theories and techniques to see if they work in practice. They don’t like ‘beating around the bush’ and tend to be impatient with ruminating and open-ended discussions. They are essentially practical, down-to-earth people who like making practical decisions and solving problems. Their philosophy is ‘if it works it’s good’.

In any organisation there will be a mix of activists, reflectors, theorists and pragmatists: people whose way of learning and approach to problems and decision-making is primarily, even completely, characterised by the forms of behaviour described under these headings. What is important is to identify the different learning styles and approaches so that these can be matched to needs, and so that those dominated by one style more than any other can improve their effectiveness by developing a wider range of styles to suit their present and future roles and tasks.

The concept of learning styles is an important development because it helps to throw some light on how people actually learn. It indicates that there are varying approaches which can be related to different training methods.

In summary, learning theories and the application of learning principles are the cornerstone of training. Silverman (1970)30 succinctly identified ten basic generalisations from learning theory which are particularly pertinent to the training situation. These are as follows:

1. Trainees learn best by making active responses. People learn best by doing and getting involved, not just listening.

2. The responses that the trainee makes are limited by their abilities and by the sum total of their past responses.

3. Learning proceeds most effectively when the trainee’s correct responses are promptly reinforced.

4. The frequency with which a response is reinforced will determine how well it will be learned.

5. Practice in a variety of settings will increase the range of situations in which learning can be applied.

6. A motivated trainee is more likely to learn and to use what they have learned than an unmotivated trainee.

7. The trainee should be encouraged to find summarising or governing principles to help to organise what they are learning.

8. The trainee should be assisted to learn to discriminate the important stimuli in every situation so that they can respond appropriately.

9. The trainee will learn most effectively when they can learn at their own pace.

10. There are different kinds of learning and they may require different learning conditions.

These and other issues relating to learning must be borne in mind when designing training as the success of any training can only be gauged by the amount of learning that occurs and is transferred to the job. Too often, unplanned, uncoordinated and haphazard training efforts significantly reduce the learning that could have occurred.

4.6 A systematic training approach

Training and learning will take place, especially through informal workgroups, whether an organisation has a coordinated training effort or not. But without a well-designed systematic approach to training, what is learned may not be what is best for the organisation.

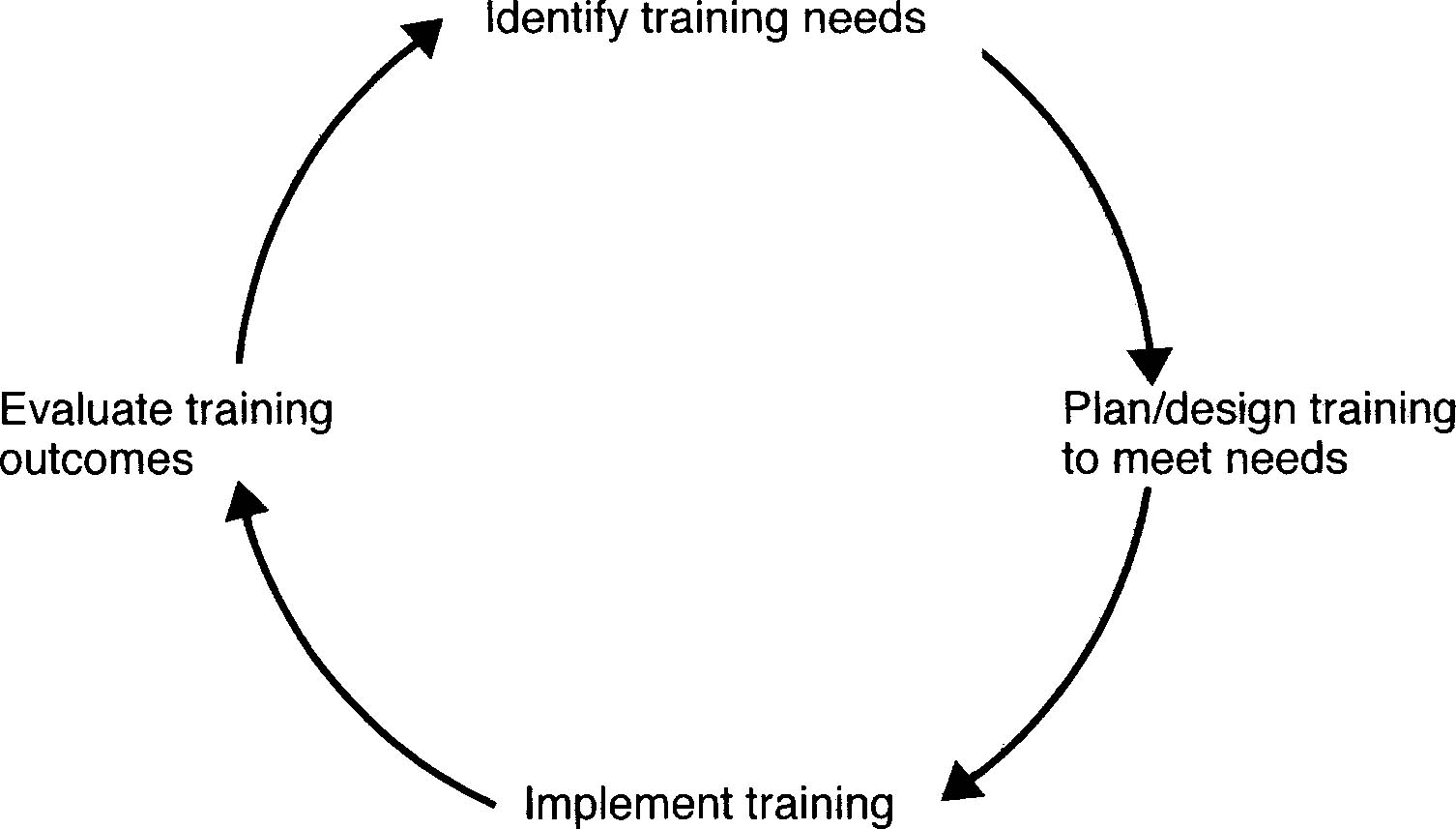

Figure 4.2 shows the relevant components of the four major phases typically adopted in a training system. This provides a useful framework for the systematic application of learning at the workplace. This crude systematic approach forms the basis of many of the subsequent models of the training process. It is simple, logical and illustrates the dependency relationship between the different steps. However, there are those who feel that this is too mechanistic and clear-cut, suggesting, for example, that needs may be identified at the evaluation stage.

Figure 4.2 Simple systematic training cycle

More comprehensive and sophisticated approaches have been developed. These are, in essence, expanded versions of the basic systematic cycle (see Figure 4.3). In the assessment phase, the need for training is determined and the objectives of the training are specified. The training is then planned, designed and implemented on the basis of these objectives. The evaluation phase is crucial and focuses on measuring how well the training accomplished what it originally intended to do.

Figure 4.3 Enhanced training process

4.7 Identifying training needs: the assessment phase

Training is largely designed to help the organisation accomplish its objectives. Determining training needs is the diagnostic phase of setting training objectives. The ability to identify areas in which training can make a real contribution to organisational success is crucial. This is a method of ‘gap’ analysis; it is aimed at determining the difference or gap between actual and required performance. The inherent assumption, which must be tested, is that the shortfall in performance is caused by deficiencies in knowledge, skills or attitude.

For over 30 years the dominant framework for identifying training needs has been McGehee and Thayer’s (1961)31 three-category needs analysis approach: organisational analysis, occupational analysis and personal analysis. In reality, costs and other resource constraints may determine a more specific interventionist strategy rather than a blanket and costly coverage. Accurate learning objectives derived from real needs should underpin blanket or ad hoc strategies.

Organisational analysis

Needs assessment should diagnose present problems and future challenges which are to be met through training and development. For example, changes in the external environment may present an organisation with new challenges and to respond effectively, employees may need training to deal with these changes. Sometimes a change in the organisation’s strategy can create a need for training; for example, the introduction of new products or services usually requires employees to learn new procedures. As part of the organisation’s strategic human resource planning, it is important to identify the knowledge, skills and abilities that will be needed for employees in the future as both jobs and the organisation change. Both internal and external forces that will influence the training of workers must be considered.

Assessing organisational needs can isolate problems which may indicate the need for training of groups of employees or of particular individuals. The first way of diagnosing training needs is through organisational analysis, which considers the organisation as a system. Goldstein (1986) described organisational analysis as the study of ‘the system-wide components of an organisation that may have impact on a training program(me) … [including] an examination of the organisational goals, resources of the organisation, climate of training, and internal and external constraints present in the environment’.32

Organisational analysis can be undertaken using a variety of sources of information: human resource data can show training weaknesses; departments or areas with high turnover, high absenteeism, low performance or other deficiencies can be pinpointed, and their specific training needs investigated. Specific sources of information for organisational level needs analysis may include grievances, accident records, observations, exit interviews, customer complaints, waste/scrap quality control data, etc.

Occupational analysis

It is generally accepted that some examination of the job itself should be carried out in order to determine what should constitute an appropriate training programme. It is also accepted that this involves a description and a breakdown of the tasks which make up a job into elements of some kind. However, no general agreement exists as to how this should be accomplished as there are a number of different approaches and techniques which may be adopted.

An examination of the training literature and discussions with people in the field reveals that genuine difficulties exist over terminology. This is perhaps most apparent in the analysis of activities to derive training content. The terms job, skills and task analysis, which might be used interchangeably, represent different processes, or even refer to different stages within the same process.

Job analysis is ‘the process of examining a job in detail in order to identify its component tasks. The detail and approach may vary according to the purpose for which the job is being analysed, for example, training, equipment design, work layout’.33 There are those who have suggested that the term ‘job’ is person-oriented34 and that for training purposes the more specific term ‘task analysis’ is preferred.

Skills analysis relates to a detailed analysis of the skilled physical movements involved in manual operations and although they are useful in some training situations, their range of application is limited, particularly in supervisory and management roles.

Task analysis is probably the most important form of analysis for training purposes. It focuses on the objectives or outcomes of the tasks that people perform and provides an extremely flexible and useful method for analysis. This includes a detailed examination of each task component of a job, performance standards of a job, methods and knowledge the employee must use in the performance of job tasks and the ways in which employees learn these methods and acquire the needed knowledge.35 In other words, task analysis ‘results in a statement of the activities or work operations performed on the job and the conditions under which the job [or group of similar tasks] is performed’.36

In order to undertake an occupational analysis (be it job, task or skills analysis) effectively, it is necessary to know what the job requirements in the organisation are. Job descriptions and job specifications provide information on the performances expected and details necessary for employees to accomplish the required work. By comparing the requirements of jobs with the knowledge, skills and abilities of employees, training needs can be identified.

Personal analysis

Personal analysis focuses on individuals and how they perform in their jobs. Such information can be obtained from a variety of sources, for example, directly observing job performance, reviewing supervisory evaluations of performance, using diagnostic tests such as written ability tests, comparing behaviour of well performing employees with those of poorly performing employees, and discussing with employees their individual job performance and factors that may inhibit that performance. The use of performance appraisal data in undertaking this individual analysis is the most common approach.

4.8 Setting training objectives: the planning phase

Once the mismatch between actual and required performance has been identified, the question Is training the answer? needs to be asked. Is the mismatch related to a learning situation? Often, if care is not taken, situations which require counselling or disciplinary action are handed over as training situations to be resolved. Training is not always the answer to every managerial problem, and should be treated as a development opportunity giving individuals time to learn, rather than remedial action. It is true, however, that there are times that retraining someone whose training has not been adequate in the first place is required. Training and development should be a part of the overall training strategy of the business and germane to those objectives. It should not be treated as a shot in the arm to deal with an immediate situation when other solutions, perhaps less palatable, are available.

When the need for training has been identified, the next stage in the systematic training process is to set training objectives. An objective is a specific outcome that the training programme is intended to achieve. These are typically set for the trainee rather than the organisation, though the outcome of training should ultimately lead to the achievement of organisational goals. Training objectives define performance that the trainee should be able to exhibit after training. They should be stated explicitly, and answer three questions:37

1. What should the trainee be able to do after training?

2. Under what conditions should the trainee be able to perform the trained behaviour?

3. How well should the trainee perform the trained behaviour?

Explicit objectives serve a number of purposes. One of the most important is that they assist in developing the criteria to be used in evaluating the training outcome.

Furthermore, these explicit objectives must be aligned to the overall strategic objectives of the business. Training is a cost centre, if only in terms of the time taken away from the job by both trainer and trainee. Therefore, it is important that any training undertaken meets individual, departmental and organisational objectives. This is also true of long-term development of staff, which should be in line with the organisation’s human resource plan.

4.9 Selecting training design and methods: the design phase

Once the question Who needs training? has been answered by conducting an analysis of training needs, and training objectives have been set, appropriate training design and methods can be selected. However, there is a need to think beyond simply sending someone on an off-the-job training course either internally or externally.

It is at this stage that thought should be given to the trainees, who they are and what they know already. What follows is a checklist of questions and activities which could be used in designing training and selecting appropriate training methods, in order both to maximise the learning experience and the cost effectiveness of the training opportunity.

In deciding the most appropriate content and design, it is important to ask the question — What is the purpose of the training? The purpose will dictate, to a large extent, the design and training methods adopted.

An introduction to a job or function (induction)

As well as following naturally from recruitment and selection, induction should also consider the initial training and development that anyone needs on joining either the new organisation or taking on a new function within it.38 As well as dealing with the initial knowledge and skills needed to do the job, in the case of a new organisation, it should also deal with the structure, culture and activities of the organisation.

Basic understanding of a job or function

Effective job analysis39 should result in a list of key tasks which are the core components of the job. Initial training of this kind would be separate from the induction process but would follow on from it immediately.

Provision of skills to carry out the job

Some jobs have key skills elements attached to them, for example, working in a customer interface situation would require not only knowledge about dealing with complaints but also the key behavioural skills of the likely interactions. This acquisition of skills is a separate entity from acquiring knowledge and should be considered as such. It is likely to be far less quantifiable and also take longer to train and practise, requiring feedback from coach or mentor to help the development process.

Developing specialist knowledge

This area could cover the specialist skills required in particular functions, for example, accounting or human resource management itself, or alternatively knowledge about particular customers who are key account holders. It is likely that this is development which will need to be acquired over a longer period and will necessitate progress checks at regular intervals.

Broadening knowledge of the business

This allows training and development into the wider context beyond an individual’s job or function. It allows for commitment to the goals and mission of the organisation as a whole and is often achieved through guided reading as well as off-the-job seminars and conferences.

Changing attitudes about a job or function

This type of training objective is becoming increasingly important as organisations go through significant changes and attempt, in line with these, to change their organisational culture.

Will both content and method be suitable for employees’ learning styles?

We have talked earlier in this chapter about the importance of establishing individuals’ learning preferences before designing and undertaking any training.40 Every time training takes place, it is important that this information is reviewed and methods used are compatible with the individual’s preferences. This will also be true of the person doing the training.

We have already looked at how people learn, and have suggested that for some learning styles, off-the-job training would not provide the best environment in which to learn. What are the alternatives to formal off-the-job training? There are several alternatives including:

• Individual coaching: To be effective this method of training needs to be planned and executed with thought. First, this means providing the person who is going to be the coach with training in coaching skills and then providing time slots in their own schedule for coaching to take place. They can then identify opportunities in their own and others’ daily work as development opportunities, helping the other person learn how to do the job and providing continuous feedback as to progress. This can also be seen as a learning opportunity for the coach.41

• Prescribed reading: Manuals or books may be available through open learning centres in organisations which cover particular facets of an individual’s job which may be helpful for individuals to be aware of. As with coaching, time needs to be set aside for individuals to complete the task outside daily work. Short pieces of text about key tasks could be created which could then be given to individuals to use and keep for future reference.

• Open learning: Open learning texts and courses are available in the marketplace, which enable people to study in their own time, and at their own pace, a subject area which both interests them and at the same time enhances their training in the workplace. This is particularly true of management and supervisory training and more and more opportunities are presenting themselves in areas such as customer service. Alternatively, organisations may have an open learning centre which either provides a library of such texts or may be able to produce material germane to the individual’s area of work if it does not exist already, or to adapt existing specific material.

• Project work: One of the ways in which new skills can be acquired is through specific project work. From time to time, opportunities will exist to move staff on a specific project which while being part of the department’s work is not necessarily normally part of the individual’s work. This gives the opportunity to acquire new skills, and to manage a whole project from start to finish.

• Job rotation: In departments where a wide variety of jobs are being done, it is possible to rotate individuals through them. This has the advantage of widening the skills base of individuals as well as ensuring that everyone is familiar both with whole tasks (if they normally work on parts of sequential tasks) and for covering when there is sickness and absence. Of course, at the same time there is a need to ensure that the right on-the-job training or coaching takes place in order that people can complete the new tasks. Principles of job design42 suggest that skills variety, task identity and task significance contribute to motivating employees. Thus having the opportunity to see whole tasks through and learn a variety of new skills and tasks through this medium not only enhances learning but also motivation.

• Job attachments: This is a similar form to job rotation, in that people are given the opportunity to learn new tasks. In this case, however, they will be attached to another department or particular job other than their own for an extended period, usually from three months to a year. During this period they would be expected to do the other job as if it were their own, thus taking advantage of other training methods in order to enhance their knowledge and skills in this new role.

• Further education courses: There are many job-related and professional courses available at universities and tertiary colleges which will enhance knowledge and skills. These can also lead to qualifications or can qualify for some professional bodies’ continuous professional development (CPD) schemes.

• Computer aided learning: Many learning packages have now been created for use on personal computers. These give people the opportunity to work at their own pace and in their own time on their training, in the same way that open learning does in a non-digital environment.

• Mentoring: Mentoring as a form of training opportunity has increased in popularity. A mentor is someone, usually a colleague, at the same or from a higher level in the organisation, but who is not in a line management relationship with the individual being mentored. They then become someone with whom the individual can go and discuss work-related issues and in particular their own career development. The advantage of this system is that it is outside the normal work relationship and so an overview can be given without prejudice. The mentor’s role is to encourage the protégé and to use their own experience to help manage difficulties which may arise. Many organisations are now investing in formal mentoring schemes, in particular for graduate trainees or highflyers. In the informal sense, individuals may have more than one mentor to whom they can go for advice dependent on the situation.43

• Sitting with Nellie: This form of training is perhaps the oldest and most common form to be found in organisations and was particularly popular in production or manufacturing organisations. The trainee is assigned to an experienced member of staff in a similar way to coaching. More often than not though they do not have the training to coach. They are expected to pass on what they know as quickly as possible in order to make the trainee effective at the job.

4.10 Conducting the training: the implementation phase

Training is a partnership between the manager, the trainer and the person being trained. Unless agreement is arranged, it is unlikely that the learner will be sufficiently motivated to undertake the training, nor will the person doing the training be clear about what needs to be achieved. Thus all parties need to sit down and agree objectives for the training as well as clarify why the training is being undertaken. This may be as a part of an annual review of training needs or part of a performance management or appraisal scheme operating in the organisation as a whole. At this meeting, agreement should be reached about the timescale under which the training is to take place as well as how the training will be monitored and evaluated.

Consideration with regard to the timing of the training should be made. When the training should start and finish and, in relation to this, what the best time of day would be to take time away from the workplace. It is important to find a venue away from the normal place of work so as to avoid interruptions. Making sure that any equipment that might be needed is available, checking that it works and changing the seating arrangements in order to make people feel more comfortable with their surroundings are also important considerations.

There are other practical issues which should be borne in mind while conducting the training, for example, ensuring that the most appropriate yet varied methods are chosen to put material across. Some 75 per cent of information is taken in visually and learning by doing is by far the best method of all. Trainers should work with methods that they are most familiar with in order to ensure that the delivery keeps people alert and interested. Preparing thoroughly and rehearsing the session before the event, particularly if the trainer is inexperienced, is essential. This should include practising any exercises included in the programme to ascertain how and why they work.

If people are coming from other than the immediate area, sending out instructions for the venue beforehand and briefing people as to the aims and objectives of the session before the event so that they have time to think about it and prepare themselves is important.

Stating the objectives clearly at the start of the session is vital so that everyone knows what is going to happen, and why they are being trained for this particular task. In good presentation style, ‘Tell them what is going to be said, say it, then tell them what has been said’.

The trainer can develop the content by expanding existing knowledge and skills through explanation and demonstration. They can check and recap for any knowledge after the session by providing trainees with the opportunity to undertake a practical exercise. The old adage ‘How do you eat an elephant?’ — ‘in bite-size chunks’ is a useful one. Little and often helps people to absorb knowledge and skills.

Trainers should look for and use feedback from learners to make sure that understanding has taken place. Watching body language and checking by asking questions helps. On the basis of this feedback, trainers may need to modify their approach. In other words, no amount of planning and design can compensate for the receptiveness of a trainee. Adapting to learners’ needs is the key to successful implementation of a training programme.

4.11 Evaluating training outcomes

Evaluating training outcomes cannot be said to be simple, since nothing which involves the measurement of human behaviour, or even the results of human behaviour, is ever simple. Evaluating training is an attempt at determining what changes take place in skills, knowledge and attitudes of employees as a result of training and how far these changes are beneficial to the organisation’s objectives.

Although there are many approaches and styles to evaluation, there is quite a high degree of consistency about what is considered to be the primary purpose underlying evaluation activities. Advocates of evaluation agree that it is an attempt to improve the quality of training, and that it might involve, therefore, mechanisms to prove that this is done as well as determining what learning has taken place.44 Emphasis of these three purposes has changed over the years and has roughly parallelled the historical development of evaluation.

Proving

Proving the worth and impact of training was historically the first primary function of evaluation.45 This form of evaluation has been popular as a mechanism for proving to the organisation that training and development add value to its strategic direction by linking back to strategic goals and contributing to the identification of training needs at an organisational level. As Shipman (1983) stated, ‘It should be telling someone whether action has been successful and where fresh investment should be made’.46

In addition, the cost-benefit analysis of the training function is important as internal training departments increasingly compete with outside providers. The ability to demonstrate that the training is not only effective but also less costly than other alternatives is important to organisations where outsourcing of peripheral functions is becoming the norm. Training and development delivery is an easy option to outsource as the number of outside providers grows.

Improving

The improving purpose has been stressed partly as a reaction to the difficulties of proving anything about the effects of training. Thus, the ‘primary purpose of gathering evaluation data is to provide the trainer with information which will help him increase their subsequent effectiveness’.47 Hamblin (1974) concurs with this sentiment and adds that the purpose of evaluation ‘is not to determine if desired changes did occur but rather determine what should happen next’.48 This is the most common form of evaluation undertaken usually by the training function itself in the form of end-of-course or post-course questionnaires. The purpose of the exercise is to ask participants in training events to comment on the provision in terms of its strengths and weaknesses in order for the training itself to be changed or improved the next time it takes place. The problem with this sort of immediate response is that it may simply be a knee-jerk reaction to the process rather than a considered approach. One would also need to consider at what point and by what response one would make changes to the provision, i.e. does what one course or group of people say necessarily constitute a representative sample?

Learning

Perhaps the most important, and in most organisations the most under-used, form of evaluation is that of measuring the learning which has taken place as a result of the training. One of the reasons for this, is that it is the most difficult to achieve. This brings into force the relationship between setting specific objectives as a result of the identification of training needs and changes in performance as a result of the training. An advantage of this type of evaluation is that it embraces the relationship between the training function and the trainee’s line manager. Strategies for accomplishing this include pre- and post-discussion. This includes setting objectives and measuring the result, often as a part of an ongoing performance management system, or the setting of specific project work which is reviewed at a distant point after the course. A potential problem with this is that it often means a somewhat subjective approach unless the training is skills-based, in which case, increases in productivity are more easily measured. More difficult is the measurement of changes in behaviour, although the increase in the use of 360 degree feedback is helping this process.

It is clear that all training and development has a purpose, thus the evaluation of that training should also have a purpose and should form an integral part of the training process.

4.12 Conclusions

Training aims to change behaviour at the workplace in order to increase efficiency and higher performance standards. In turn, learning is seen as the vehicle for this behavioural change. One of the themes running through this chapter is that the benefits and the responsibility of training rest with the organisation as well as the individual. Therefore, commitment to training is required from both.

Applying the principles of learning and adopting a systematic approach to training based on the identification of training needs as well as a programme, designed and evaluated on the basis of these needs, are all necessary commitments that the organisation needs to make. Likewise, individuals need to match this commitment with positive motivation towards training. It is only when this duality of purpose is achieved that the real benefits of training for both the organisation and the individual come into play.

4.13 References

1. Department of Employment. Training for jobs. Cmnd 9135, London: HMSO, 1984.

2. Department of Education and Science. Better schools. Cmnd 9469, London: HMSO, 1985; Department of Employment and Department of Education and Science. Working together: education and training. Cmnd 9823, London: HMSO, 1986; Department of Education and Science. Higher education: meeting the challenge. Cmnd 114, London: HMSO, 1987; Mangham IL, Silver MS. Management training: context and practice. Bath: ESRC/DTI, School of Management, University of Bath, 1986; Constable J, McCormick J. The making of British managers: a report for the BIM and CBI into management training, education and development. Corby: BIM, 1987; Handy C. The making of managers: a report on management education, training and development in the USA, West Germany, France, Japan and the UK. London: National Economic Development Office, 1987; Department of Trade and Industry. Competitiveness: helping business to win. Cmnd 2563, London: HMSO, 1994 (First Competitiveness White Paper); Department of Trade and Industry. Competitiveness: forging ahead. Cmnd 2867, London: HMSO, 1995 (Second Competitiveness White Paper); Department of Trade and Industry. Competitiveness: creating the enterprise centre of Europe. London: HMSO, 1996 (Third Competitiveness White Paper).

3. O’Brien R, Manpower Services Commission, Chairman, 1982.

4. Training for jobs.

5. Finegold S, Soskice D. The failure of training in Britain: analysis and prescription. In: Esland G ed. Education, training and employment: volume 1: educated labour: the changing basis of industrial demand. Wokingham: Addison Wesley, 1991.

6. Royal Commission on Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations. 1965-1968. London: HMSO, 1968; National Economic Development Office. Management education in the 1970s. London: HMSO, 1978; Manpower Services Commission. Skills monitoring report. Sheffield: MSC Evaluation and Research Unit, 1986; Skill needs in Britain. London: Public Attitude Surveys, 1995.

7. Daly A. Education, training and productivity in the US and Great Britain. London: NISR, no. 63, 1984; Worswick GD. Education and economic performance. Aldershot: Gower, 1985; Steedman H. Vocational training in France and Britain: the construction industry. NI Economic Review May 1986.

8. MSC. A challenge to complacency: changing attitudes to training: a report to the Manpower Services Commission and National Economic Development Organisation. Sheffield: MSC, 1985.

9. Department of Trade and Industry. Competitiveness: forging ahead.

10. Hogarth T, Siora T, Briscoe G, Hasluck C. The net costs of training to employers: initial training of young people in intermediate skills. Labour Market Trends 1996; 104(3): 121–126.

11. Hogarth et al. Net costs.

12. Hogarth et al. Net costs.

13. Park A. Individual commitment to learning: individuals’ attitudes. Sheffield: Department for Employment and Education Research Series, no. 32, 1994.

14. Gallie D, White M. Employee commitment and the skills revolution: first findings from the Employment in Britain Survey. London: PSI, 1993.

15. Department of Employment. Glossary of training terms. London: HMSO, 1971.

16. Hesseling P. Strategy of evaluation research in the field of supervisory and management training. Assen: Van Gorcum, 1971.

17. Oatey M. Economics of training with respect to the firm. British Journal of Industrial Relations 1970; 8(1): 1–21.

18. Manpower Services Commission. Glossary of training terms. London: HMSO, 1981.

19. Wexley KN, Latham GP. Developing and training human resources in organisations. London: Scott Foresman, 1981.

20. Goldstein IL. Training in organisations: needs assessment, development and evaluation. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole, 1986.

21. Bass BM, Vaughan JA. Training in industry: the management of learning. London: Tavistock, 1966.

22. Campbell JP, Dunnette MD, Lawler EE, Weick KE. Managerial behavior, performance and effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970; Laird D. Approaches to training and development. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley, 1983.

23. Campbell et al. Managerial behavior; Laird, Approaches.

24. Campbell et al. Managerial behavior; Laird, Approaches; Digman LA. Management development: needs and practices. Personnel 1980; 57, July-Aug.: 45–57.

25. French WL, Bell CH Jr, Zawacki RA eds. Organisational development: theory, practice and research. Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin, 1994.

26. Bass and Vaughan, Training in industry.

27. Herzberg F. Work and the nature of man. Cleveland: World Publishing Co., 1966.

28. Kolb DA, Rubin IN, Mclntyre JM. Organisational psychology: an experimental approach. London: Prentice Hall, 1974.

29. Honey P, Mumford A. Using your learning styles. Maidenhead: Peter Honey, 1986.

30. Silverman RE. Learning theory applied to training. In: Otto CP, Glaser RE eds. The management of training: a handbook for training and development personnel. London: Addison Wesley, 1970.

31. McGehee W, Thayer PW. Training in business and industry. New York: Wiley, 1961.

32. Goldstein, Training in organisations.

33. Department of Employment, Glossary.

34. Annet J. Learning in practice. In: Warr P ed. Psychology at work. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974.

35. Mager RF. Preparing instructional objectives. Belmont, CA: David S Lake, 1984.

36. Goldstein, Training in organisations.

37. Mager, Preparing.

38. Thompson R. Managing people. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993.

39. Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Motivation through design of work — a test of theory. Organisational Behaviour and Human Performance 1976; 16: 250–279.

40. Honey, Mumford, Learning styles.

41. Thompson, Managing people.

42. Hackman, Oldham, Motivation.

43. Clutterbuck D. Everyone needs a mentor: fostering talent at work. London: IPD, 1991.

44. Easterby-Smith M. Evaluation of management education, training and development. Aldershot: Gower, 1986.

45. Odiorne GS. The need for economic approach to training. Journal of the American Society of Training Directors 1964; 18(3).

46. Shipman MD. Parvenu evaluation. In: Smetherham D ed. Practising evaluation. Nafferton Books, UK, 1983.

47. Warr PB, Bird M, Rackham N. Evaluation of management training. Aldershot: Gower, 1970.

48. Hamblin AC. Evaluation and control of training. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1974.