5 Culture, organisation development and change

The most pressing problems facing today’s leaders are those associated with change. Government, industry, unions and professional bodies are all having to adapt to their changing environments. The fortunate ones have been able to adapt by voluntarily managing a process of incremental or fundamental change. The less fortunate ones have been forced into unpopular change decisions involving downsizing and mergers in order to survive. Today’s leaders continue to seek strategies which will enable their organisations to cope with the need to change while satisfying a range of financial and social criteria. Organisation development (OD) represents a body of knowledge to help them in this task.

Although there is a vast literature on OD, its definition and boundaries are unclear. This is all to the good, because it is a sign of a growing and dynamic field of knowledge, and one which has been adapting to new research findings and theories. What help can OD give to those managers who are trying to improve the effectiveness of their organisations in a changing environment? Or to put it another way, the competitiveness of their organisations?

This chapter attempts to answer these questions by doing the following:

1. identifying the main influences which have shaped the emergence and development of OD;

2. presenting a framework which clarifies the nature of the conceptual and methodological resources which OD makes available to the manager;

3. outlining some ways in which these OD resources can be most effectively utilised by management.

5.1 Main influences on OD

OD theorists and practitioners are continually trying to find valid answers to two basic questions: What changes do organisations need to make to their culture, and to the way in which they organise and manage themselves, in order to remain competitive? How should organisations go about introducing these changes so as to achieve their objectives efficiently and effectively? These content and process issues have been particularly influenced by the concepts and approaches outlined below.

Open socio-technical systems model

A system is an orderly grouping of different components for the purpose of achieving some given objective. The essential difference in thinking of an organisation as an open rather than a closed system is that due emphasis is given to its dependence upon the environment for its continued existence. Closed system thinking tends to encourage the adoption of a problem-solving approach which focuses attention on internal causes of stress, rather than those causes stemming from an organisation’s relationship with its external environment.

The open system model of an organisation is basically very simple. The organisation is seen as:

• importing energy from its environment (in the form of labour, materials, finance and equipment);

• transforming this energy into some product or service which is characteristic of the system (e.g., paper products, financial services);

• exporting the product or service into the environment;

• re-energising the system with further resources from the environment.

Thus the open system model highlights the need for an organisation to adapt to changes in its environment. This model has led OD theorists to research and propose those characteristics which are likely to increase the capacity of an organisation to adapt to environmental change. The term organisational effectiveness, as opposed to organisational efficiency, is often used to denote the goal of enabling organisations to grow and survive over time, rather than achieving short-term efficiency or profitability. OD is very much concerned with organisational effectiveness, and therefore with those organisational properties which are conducive to adaptability, flexibility, and innovativeness. Another term which is increasingly being used to convey a similar idea is ‘the learning organisation’.1 This highlights the capacity of an organisation to learn in the process of doing, i.e. to learn how to do things better as a result of experience.

The socio-technical component of the open system model has its origins in the pioneering work of the Tavistock Institute for Human Relations in London. Their research in British coal mines and in Indian textile mills demonstrated the interdependence of the social and technical sub-systems within an organisation.2 Mechanisation inevitably had repercussions on roles in the social system, and re-structuring had implications for the efficiency of the technical system. The main lesson to be learned was that when introducing changes to the workplace, the needs of both the technical and the social system have to be taken into account. Ignoring or misunderstanding social needs will eventually be reflected in such criteria as productivity, quality of output, accidents, absenteeism and turnover.

Subsequent research has increased our insight into the relationships between technology, organisations and their environments. In the well-documented study of the electronics industry in Scotland, Burns and Stalker3 found that while the less successful organisations tended to be ‘mechanistic’, i.e. a greater reliance placed on formal rules and procedures, narrow spans of control, and decision-making at the highest levels, the successful organisations were more ‘organic’, i.e. less emphasis on formal procedures, wider spans of supervisory control more common, more decisions taken at lower levels. The explanation for these findings was that organically structured organisations were able to adapt to change more quickly, and a better match therefore for changing times.

Similarly, in a study of 100 firms in South East Essex, Woodward4 found that as the technology changed, so certain structural characteristics changed (e.g. the span of control of the chief executive). She found also that different technologies imposed different kinds of demands on organisations, and that these had to be met by an appropriate structure. Organisations with structural characteristics close to the pattern for their particular technology tended to be more effective.

A refinement to the organic/mechanistic model came from the work of Lawrence and Lorsch,5 who further elucidated the complexity of the relationship between an organisation and its environment. They drew attention to the fact that different parts of an organisation may interact with quite different environments. Thus while an organic structure and climate may be appropriate for the R&D department, a mechanistic structure better suited the production department.

Human psychology and human relations

OD has been particularly influenced by certain values associated with humanistic psychologists such as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers which stress the importance of developing human potential, giving individuals opportunities to influence their work environment, providing them with interest and challenge in their work, and recognise their unique and complex needs. These values were very visible in the pioneering OD activities of such Americans as Chris Argyris and Douglas McGregor. They received new impetus through the almost missionary zeal of Thorsrud, Cherns and others in Europe.6 The latter found expression in the industrial democracy (ID) and quality of working life (QWL) movements. In the UK a visible sign of their success is the promotional and advisory activities of the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) whose mission statement emphasises ‘as part of our approach we seek to help organisations to become more effective by improving the quality of working life’.7

The human relations movement was influenced by the value systems referred to as well as those studies which highlighted the importance of social relationships, group membership and leadership style in determining the performance and well-being of people at work. Seminal studies included: the Hawthorne studies;8 Lewin’s studies9 of the benefits of group decision-making; Coch and French’s study10 of the superiority of a participative approach to change. Of particular importance to OD were the early group approaches to individual learning and change as developed by the National Training Laboratories, and referred to as T-groups or sensitivity training. Most of the early OD giants such as Bennis, McGregor, Argyris and Schein, were all heavily involved in T-groups.11

Force field model

One of the most enduring conceptual models in OD was originated by an American social psychologist, Kurt Lewin.12 In order to cope with various forces which can facilitate or inhibit change, Lewin formulated his 3-step model.

1. Organisations have an inherent capacity to maintain the status quo by a balance of driving and restraining forces. In order to introduce change, one must disturb this equilibrium by introducing new forces, removing old ones, or both. This unfreezing process can be achieved by making people feel dissatisfied with the present state of affairs, and motivating them to seek improvements.

2. Once the unfreezing process is well under way the changing process can be initiated, and participants encouraged to seek new solutions to old problems.

3. The final phase is to refreeze or stabilise the forces operating in the new situation. This involves ensuring that the changes are legitimised and integrated into the organisation so that their maintenance is not dependent upon temporary forces, such as the presence of an external consultant.

The value of this unfreezing/changing/refreezing model is that it encourages those responsible for managing change to identify those forces which are supporting the desired change, and those opposing it. A systematic analysis of these opposing forces is more likely to result in a successful strategy for change.

Action research

The action research approach to change was another valuable contribution made by Lewin.13 He argued that research in the behavioural sciences would have only limited impact if the researcher was involved solely in the research process (i.e. developing hypotheses and gathering information), and not in the subsequent action process (i.e. planning, implementation and evaluating subsequent actions). Pioneering studies of the action research mode include: Lewin’s work on changing food eating habits, Coch and French’s study on overcoming resistance to change, and Jaques’ studies14 in the Glacier Metal works in the UK. Many OD practitioners continue to adopt this process model when intervening in organisations.

Change agents

Initially OD change agents were the internal or external consultants who intervened in the processes of organisations in order to bring about certain changes as effectively as possible. Well versed in psychology or the behavioural sciences, their style of intervention was very much that of a joint problem-solving approach. To illustrate this pioneering style, and the reasons for it, it is helpful to compare and contrast three types of role relationships which a consultant can adopt towards a client system: the expert, the teacher and the counsellor.

The expert: The client system experiences a problem; it approaches a consultant with the expectation that the latter will diagnose and prescribe a solution. The consultant, put in the position of expert, plays a fairly directive role. Often the client prejudges the problem by approaching a consultant who is an expert in a given type of solution, e.g. management by objectives, assessment centres, autonomous work groups. This sort of relationship has many attractions: the solutions applied have usually already been researched and developed by other organisations, thus reducing cost and risk of failure; the employment of an expert generates confidence in what is being done, and provides a feeling of security; if the consultant’s solution is not attractive or is threatening, it can often be rejected or shelved with the minimum of disturbance to the client system. Possible drawbacks include:

1. Superficial diagnosis and treatment. Sometimes the function of the expert is merely to provide additional authority to introduce changes which top management see as desirable.

2. The non-participative style of many experts may arouse unnecessary resistance to change, particularly where this involves breaking social norms.

3. The expert’s terms of reference may severely limit the area of the client system within which he or she can operate. Thus the changes proposed or introduced may be incompatible or threatening to other sub-systems.

4. Solutions applied may be the result of a consultant’s sales ability or of current fashion, rather than the outcome of a proper diagnosis of the problem.

The teacher: Here the consultant is primarily concerned in bringing about change through the transmission of knowledge and skill. The immediate target for change is the individual and his or her problem-solving behaviour, rather than the structural and technological variables affecting behaviour. Learning usually takes place at internal or external formal courses where simulated rather than real life problems are tackled, although in recent years formal learning experiences are increasingly being designed to be built around actual problems. The advantages of this approach include:

1. A high degree of control can be maintained over what is learned.

2. Large numbers of individuals can be exposed to new thinking at relatively low cost.

3. It is not too difficult to design formal learning situations to which participants will react favourably.

Potential weaknesses include transfer of knowledge and skills to on-the-job behaviour often being negligible (particularly where attitudes or managerial style are concerned), and individuals can find themselves on courses, especially external courses, which neither match their needs nor those of their organisation.

The counsellor: Sometimes a consultant takes on a role very similar to that of a counsellor in a therapeutic situation, i.e. a joint problem-solving approach where the counsellor does not try to impose a particular solution on the client, but encourages the client to arrive at a joint solution for which the client shares responsibility. While the counsellor is non-directive with respect to the solution, he or she does guide the problem-solving process through its various stages: the client will be encouraged to undertake a thorough diagnosis of the problem before thinking about solutions, and to choose a solution only after exploring a range of alternatives. Where an OD consultant adopts this role in relation to a client, the mechanics of the process are different since the client is part of a larger system; thus the problem-solving stages leading to change must involve those individuals, groups, or their representatives, with vested interest in the problem and the power to implement or to frustrate a proposed solution.

It is this counselling model which comes closest to describing the typical role played by a consultant in an OD intervention. The origins of this counselling approach can be seen in the thinking of Carl Rogers, in action research and in T-groups.

Learning theory

At this point there is a strong case for learning theory to be highlighted. There are two particular theories which inform the thinking and behaviour of change agents: Skinner’s reinforcement theory15 and Bandura’s social learning theory.16 In its simplest terms the former states that it is the consequences of behaviour which determine whether the behaviour will be repeated. Thus if openness in communicating with clients results in better cooperation and less resistance to change, then change agents are more likely to display this behaviour in their future interactions with clients. Reinforcement theory explains a good deal of our learning, much of which may occur without our conscious intervention. In contrast, social learning theory recognises the role of cognitive abilities in the process of learning. This theory accounts for human learning which occurs through a process of modelling or imitation. Change agents may model their behaviour when interacting with clients on Schein’s17 process consultancy approach because they are convinced that this approach is most likely to lead to a successful intervention. Similarly, their clients may be prepared to follow ‘good practice’ by learning from the experiences of their successful competitors as the British motor industry did of the Japanese.

Kolb’s18 model of experiential learning has also influenced and been influenced by OD. He defines learning as the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. The iterative process of his model follows the sequence of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. This is very similar to Lewin’s model of action research, and Kolb acknowledges his debt to Lewin. It is now generally agreed that an active, experiential approach to learning is far more effective than other more passive alternatives. This is particularly so when OD practitioners are trying to facilitate change in the belief systems underlying moribund cultures, or overcome resistance to change.

5.2 OD interventions and technology

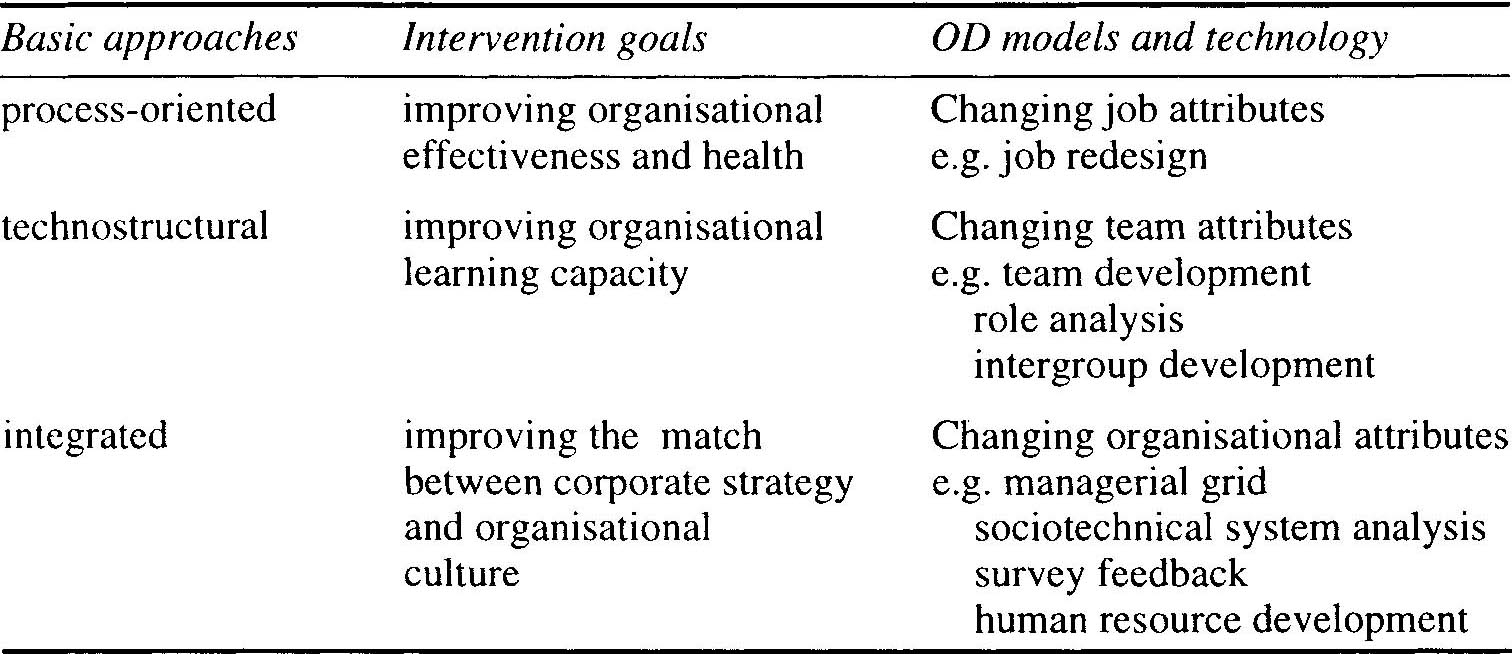

Gaining insight into the main influences on OD is the first step towards learning to use this resource for competitive gain. The next step is to become more aware of the available technology, and the situations or context in which they are likely to be valuable. Table 5.1 is a framework for exploring these issues.

Table 5.1 Intervention goals and OD technology

Intervention goals

Many of the early accounts of OD included the goals of improving organisational effectiveness or health. These terms were often used to differentiate between economic criteria applied to organisations (e.g. input-output efficiency measures), and the socio-psychological criteria which emphasised the softer variables of job satisfaction, innovativeness, flexibility, organisational loyalty and commitment, and so on. Implicit in the latter criteria was the notion that certain types of behaviour were more conducive to an organisation successfully adapting to changes and new competition in its environment. Developing these desirable characteristics became a goal of many OD programmes.

An example of an influential model of these characteristics was Likert’s System 4 or ‘participative management’.19 Key features of this ideal management system were: high performance goals; an overlapping network of cohesive teams (the linking pin structure); a climate of openness; and a supportive managerial style (individuals felt that their needs for self-esteem, etc., were being met). An extensive research programme provided the evidence which encouraged managers to develop their organisations along these lines through an appropriately designed OD programme.

One of the terms used in the OD literature is that of organisational self-renewal. This is the idea that it is not sufficient for organisations to change only in response to planned OD efforts, but that a climate for change needs to become an inherent characteristic of the organisation. This is a powerful idea given the rate and continuous nature of environmental change. As already pointed out, a similar idea is being promoted under the label of the learning organisation. An organisation which is continually able to transform itself as the need arises has an obvious competitive edge over others. From their own research and a review of the relevant literature Pedler et al.20 identify eleven characteristics of the learning organisation: learning approach to strategy; participative policy-making; information; formative accounting and control; internal exchange; reward flexibility; enabling structures; boundary workers as environmental scanners; inter-company learning; learning climate; self-development of all. Underlying this framework, and other major contributors to learning organisations such as that of Senge,21 are the OD values and systems thinking we have already mentioned.

One dimension which has aroused considerable interest in the management literature is that of organisational culture. This has been stimulated by such best-sellers as Peters and Waterman’s In Search of Excellence,22 which highlighted the key role of culture in achieving organisational success. By culture we are referring to the relatively stable and commonly held beliefs and values which underlie many aspects of behaviour displayed within an organisation. The importance of culture within the context of implementing strategic plans is clear when we consider the importance which many organisations are now attaching to quality and customer care. These attributes of products and services will only be consistently achieved if they become embedded in the culture of the organisation, hence the recent spate of organisational change programmes to bring culture into line with corporate strategy.23 Many of these programmes may be labelled ‘total quality management’ and ‘re-engineering’, and therefore may not appear to come out of the OD stable. It is true that they do not necessarily share the same value system as traditional OD (particularly when re-engineering is a euphemism for downsizing!), but many certainly draw on the proven methods of OD in the process of managing change (e.g., use of appropriate consultants as change agents, sponsorship of top management, data collection and action research, use of teams as a major driver of change).

Basic approaches

Table 5.1 lists three basic approaches: process-oriented, technostructural and integrated. Process-oriented interventions are those which are primarily directed at changing attitudes, values, norms, goals and relationships influencing behaviour. Technostructural interventions, on the other hand, are primarily directed at changing technological and structural variables influencing behaviour. Integrated interventions are those which combine both approaches. In the early days of OD the first approach dominated practice, but evaluation studies revealed its limitations and the strengths of the technostructural approaches. Now it is generally acknowledged that for effective change to take place an integrated approach is needed. Such an approach is also consistent with the principles of systems and learning theories.

Changing job attributes

Many behavioural scientists have criticised the person/job relationship which exists for the majority of people at the lower levels of organisations. These criticisms are usually based on theories of motivation, on the values underlying the quality of working life philosophy, and on certain aspects of sociotechnical systems thinking. The result is that various theorists and practitioners have arrived at certain principles of ‘good’ job design which it is argued will not only lead to greater individual job satisfaction, but to benefits to the employing organisation (e.g., better quality performance, lower turnover and absenteeism) and even to society itself in the form of improved mental health of its working citizens.24

Some OD interventions are aimed at developing the person/job relationship in the direction of normative job design principles. Thus consultants guided by Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory will seek to enrich jobs by building into them more opportunities for experiencing achievement, recognition, interesting work, responsibility, and advancement. Consultants attracted by features of sociotechnical systems thinking may want to redesign production systems along the lines of autonomous work groups, i.e. operators divided into cohesive teams which match the technology they are using, given meaningful units of work to perform (e.g. servicing all the needs of a client or assembling complete television receivers), and allowed significant autonomy in organising and monitoring their work (e.g. determine their own work pace, distribute tasks among themselves, carry out their own quality control).

There are now many examples of interventions of this nature. Buckingham25 describes a programme where job enrichment principles were successfully applied in restructuring the role of foreman in nine factories in a tobacco manufacturing firm. Most of the successful interventions reported in the UK have seen the early involvement of workers and their union representatives in the change processes.

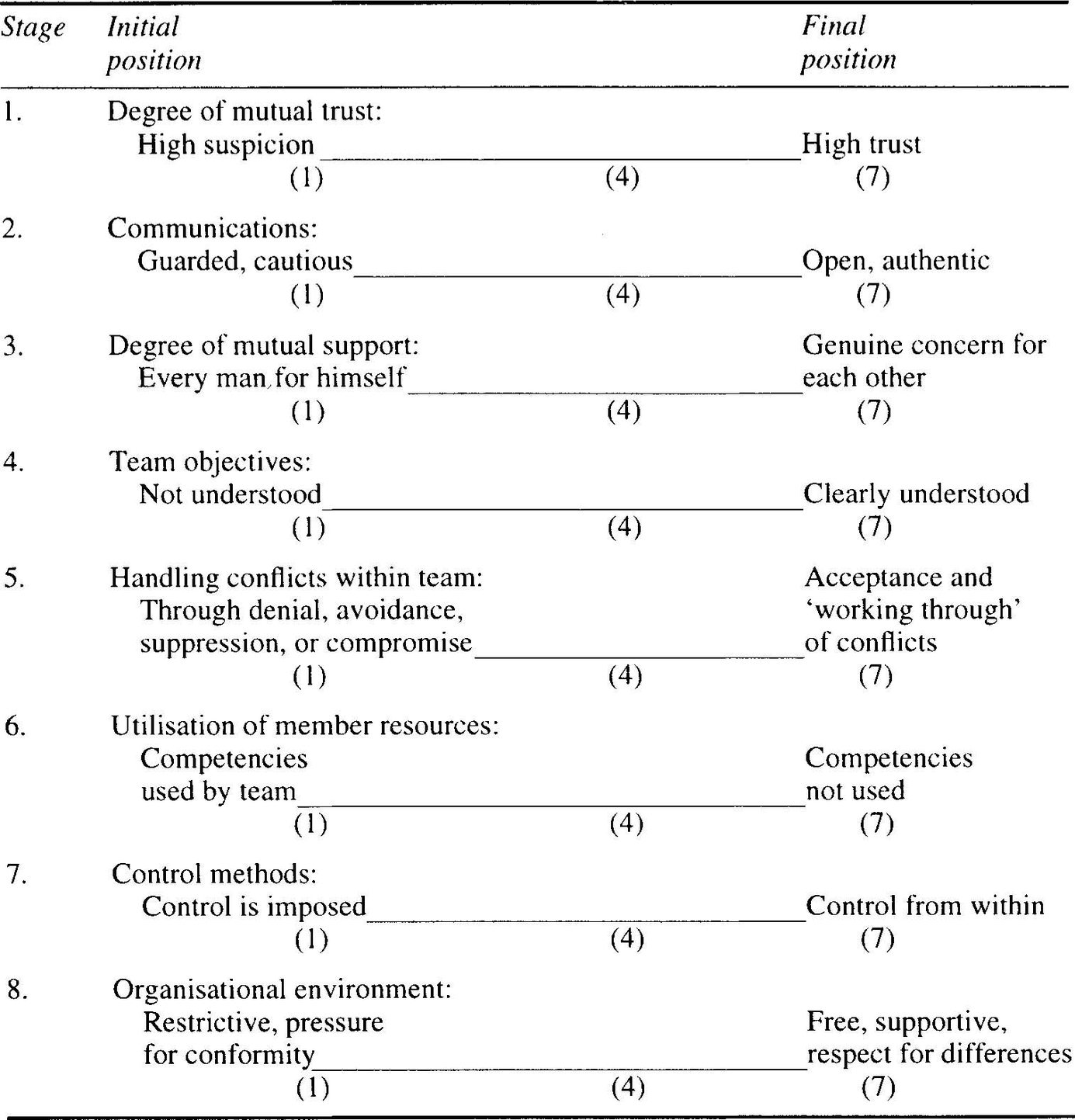

Changing team attributes

Improving team effectiveness is an important objective of organisations, since much of the work is accomplished through teams and it is recognised that work-team culture has a significant effect on individual behaviour. McGregor was typical of an early group of psychologists who tried to identify the characteristics which differentiated the more effective managerial team from the less effective team. Table 5.2 incorporates these criteria into a form which he used in an intervention activity at the Union Carbide Corporation. This form was borrowed from Bennis.26 Individuals are asked to analyse their team by rating it on a scale from 1 to 7 with respect to each of the variables. The whole team is then asked to discuss in depth the situation with respect to each variable, and to formulate ideas as to why these perceptions exist. The objective is to try and get the group to agree on those characteristics which require improvement, to formulate action plans, to implement the plans, and to evaluate the value of the team development exercise.

Table 5.2 Team development scale

Source: Bennis, Organisation development

The above is just one example of a technique used to build or develop effective teamwork. There are a host of others. Some are primarily designed to improve teamwork in an established group, some more useful for building up the effectiveness of a newly formed team. An example of the latter is the role analysis technique. This intervention is aimed at clarifying the role expectations and obligations of team members, and is particularly useful where role ambiguity or confusion exists. The assumption behind the intervention is that consensual determination of the content of roles for individual members of a team will lead to more satisfying and productive behaviour.

Often the creative and productive energy of an organisation is sapped by intergroup conflict. The factors which contribute to intergroup conflict (e.g. competition), and the consequences of conflict, are well understood in the literature and have been succinctly summarised by Schein.27 The consequences include: each group develops negative stereotypes of the other; interaction and communication between them decreases, and when it takes place, information is distorted; each thinks that it is better than the other with respect to its products, methods of work, and so on. These consequences are less likely to occur where the groups can identify a common enemy, where the nature of their tasks forces them to interact and communicate with each other frequently, or where a higher goal exists which transcends conflicting interests but is only attainable through cooperation. The problem is, how does one go about creating the conditions when intergroup conflict is the norm rather than the exception?

The development of techniques to improve sub-systems larger than single teams was a major advance within OD. The most influential model of intergroup development is that of Blake, Shepherd and Mouton.28 The following steps are typical of the process:

1. The two groups (or their leaders) meet to discuss ways of improving intergroup relations.

2. If commitment is obtained, the intervention process proceeds by asking each group to prepare two lists, working independently of each other. One list describes their perceptions of the other group; the second how they think the other group will describe them.

3. The groups come together to share the information on the four lists. Discussion is limited to questions of clarification.

4. The groups separate again, to complete two tasks: to discuss what they have learnt about themselves and the other group; to list the priority issues which need to be resolved between the two groups.

5. The groups come together to share the information on the lists, create a joint list of issues to be resolved in order of priority, generate action plans, assign responsibilities.

6. Sometimes a follow-up meeting is organised to evaluate progress on action plans and implementation.

This type of intervention has been carried out in order to improve collaboration not only between functional groups within an organisation (e.g. marketing and production), but also between representatives of head office and a field sub-system, between union and management representatives, and between representatives of merging organisations.29

Changing organisational attributes

Although the popularity of the managerial grid OD programme30 has declined, it is worth describing since it incorporates the classic features of OD. It is designed to change an organisation’s culture so that it moves from its present state to an ideal state as indicated by an influential body of knowledge. It is a good example of what may be called a ‘packaged’ OD programme, since it is mainly run by internal change agents and is structured around printed learning materials. Table 5.3 summarises the six phases of the grid; each phase consists of several days’ intensive study directed by line managers, themselves under the guidance of a skilled OD coordinator.

Table 5.3 The six phases of the managerial grid

Source: Blake et al. Managing intergroup conflict

On paper, grid OD is an excellent example of applying behavioural science knowledge to change. Attractive features of this approach are: the organisation-wide perspective; it attempts to change in a logical sequence the basic sub-systems of an organisation; it gives managers a large part of the responsibility for directing formal learning experiences; plans for change are the result of joint problem-solving; the unfreezing/changing/refreezing model underlies the structure of the learning activities; it is based on a coherent management philosophy. It is therefore not surprising that many organisations have made use of the grid. However, few have gone through all six phases, since this would involve several years of commitment for large organisations. It is perhaps significant that the most frequently quoted evaluation of the grid was published when it was first being widely marketed,31 and that apart from British-American Tobacco32 there are few examples of UK organisations having made systematic and extensive use of grid OD. It is not on methodological but on ideological grounds that the grid can be criticised. Its strong value system may be appropriate for some American companies, but not for all American companies nor for other cultures.

Survey feedback

This is an OD technique which has been in use for many years and is flexible enough to remain popular. It is an intervention technique which managers can readily comprehend since it has grown out of a fairly traditional management tool — the attitude survey. The latter is a systematic attempt to assess attitudes of organisational members to their jobs, and to existing and proposed company policies and practices. This information is used to aid management problem-solving. There are a number of reviews in the literature which amply demonstrate the potential value of attitude surveys as diagnostic instruments for throwing light on problems of morale, turnover, absenteeism and performance. On the other hand, their contributions to organisational change have often been fairly limited. It has been common practice for the full report on the survey to be treated as confidential and restricted to top management in its uncensored form. The pressure to unfreeze and change is slight, and the report can always be shelved if it threatens the status quo or criticises policies or practices which are regarded with favour by senior management.

The model which OD consultants most frequently refer to when talking about survey feedback has been described by Mann.33 The data is collected on an organisation-wide basis, fed back to top management, and then down the hierarchy through the medium of functional teams. At each feedback meeting the superior takes the chair, and together with subordinates they interpret the data, make plans for desirable changes and for introducing the data at the next level. Because of the overlapping nature of functional teams within an organisation (through the dual membership of the superior), the outcome of discussions is fed both up and down the hierarchy. Thus a head of department who is in a subordinate position at a plant meeting will report to subordinates at a departmental meeting the outcome of discussions at the plant level, and report to his or her superior at a plant meeting the outcome of discussions at the departmental level. The data fed back to a given functional team will be relevant to the problem-solving activities of that group. Thus the top management team would see the data relating to all departments and sections of the organisation, but the marketing department may only see data relating to that department and, for comparison, the average organisational responses to those questions which were also asked of other departments (comparative data can encourage the unfreezing of attitudes by creating dissatisfaction with one’s own showing).

The consultant usually attends the meetings and serves as a resource person and ‘counsellor’. Sometimes the consultant may have an important role to play in preparing a superior for a meeting, particularly if the data is critical of the management team and the superior not accustomed to joint problem-solving sessions with subordinates. The consultant may also see his or her role as encouraging the team to analyse the problem-solving processes used during the feedback sessions. This process consultation is intended to help the team learn more effective problem-solving behaviour from its own experiences — a sort of team development exercise.

There are studies to suggest that in the right cultural setting survey feedback can be a successful intervention technique.34 However, it has its limitations. The objective of survey feedback is to induce the organisation to change itself; this removes from the consultant’s shoulders the responsibility of deciding what structural and functional changes should be made. The disadvantage of this is that an organisation may reinforce its present mode of operation even if this had certain basic defects. Thus a non-union organisation is likely to remain a non-union organisation even after a survey feedback exercise. The changes made therefore are likely to be in the form of mild reform, and there are unlikely to be fundamental shifts in information flow, power handling, or basic structure. The goal of the consultant is not to suggest actions, but to enable individuals and groups to identify important problems and their solutions. This takes place in the feedback sessions. These are often voluntary; unfortunately it is the supervisors with the most problems who are least likely to hold them.

These two examples of applying OD techniques to changing organisational attributes are primarily process-led interventions. In a sociotechnical systems analysis, structural change becomes a prime target. With these and other theoretical frameworks in mind, a consultant can enter into a collaborative relationship with a client system based on the action research model. Clark describes a project of this nature.35 Over a period of three years the project was concerned with the organisational aspects of designing an advanced and technologically integrated factory that was intended to replace three semi-autonomous factories. For the most part the client consisted of a specially constituted design team drawn from R&D, production, industrial relations, finance and engineering services. The consultants did not see their task as trying to push any particular solution, but tried through jointly conducted projects in the existing factories to re-educate the client; that is, to help them to re-appraise some of the design-related beliefs they held in the light of alternative designs and their accompanying consequences.

The human resource development model

Another management model which is less clearly structured and theoretically bound than others, has been exerting considerable influence on management action and on academic research.36 This may be referred to as the human resource development model. It is characterised by renewed importance being attached to line managers becoming skilled in human resource management, by an attempt to develop human resource policies which are compatible with and reinforce corporate strategies, and by aiming to achieve high levels of employee involvement, commitment and self-development. There are many ways in which an organisation can attempt to bring about these attributes. To do it effectively in most organisations will involve changing their culture, since the changes will mean a fundamental shift in shared beliefs about the ways in which human resources are managed. Few organisations may attach the label of OD to these activities, because of the emphasis on technostructural rather than process approaches.

5.3 Effective use of OD resources

Now that we have discussed some of the intervention goals associated with OD, and some of the approaches and techniques being applied to achieve these goals, it remains to provide a few guidelines on the effective use of OD resources. The manager who is seriously interested in learning more about OD resources than is appropriate to describe here, will find it rewarding to study French and Bell37 or one of the other detailed texts on OD. By OD resources I include the conceptual models which have been developed to guide managers as to the direction in which change should be made (content issues), the tools and techniques which have been developed to effect change successfully within organisations (process issues), and the skills of OD consultants (professional change agents).

The interactive model of factors influencing planned change in Figure 5.1 is a convenient structure for this discussion.

Figure 5.1 An interactive model of factors influencing planned change

1. Mission and strategic goals: One of the weaknesses of many early OD efforts was that they tended to become an end in themselves rather than being closely linked to the organisation’s strategic plans. To indulge in OD in order to ‘make the organisation more effective’, or to follow the lead of competitors, is a luxury to be dropped as soon as finance is tight, the senior manager sponsoring the programme leaves, or the novelty value of the programme wanes. For a successful change programme to be initiated, more enduring forces need to be operating such as: agreed change objectives to support the business strategy; informed decision-making by the chief executive officer and his or her team when committing themselves to particular change objectives, and the means of achieving these objectives; adequately resourced and skilled coordinators to oversee the development and implementation of plans. Planned change must be an integral part of the strategic plans of an organisation. An OD intervention should not be seen as a means of changing the internal environment of an organisation to conform to an ideal state, but as a means of establishing a better fit between corporate strategy and the internal environment.

2. Attributes conducive to goal attainment: As we have seen in our discussion of the main influences in the development of OD; research in the behavioural sciences has led theorists and practitioners to believe that certain attributes of jobs, teams and organisations will lead to certain consequences. Accumulated research findings have meant that some of these beliefs have had to be radically modified, others have only needed fine tuning. We now know more about the conditions (e.g. dominant technology used by the organisation, national culture) under which certain types of solutions (e.g. participative management) are likely to achieve expected outcomes. Managers initiating planned change need to be well informed, or to have access to appropriate experts, before selecting given behavioural science solutions to achieve their strategic goals.

3. Methods conducive to change: Our knowledge in this area is substantial. We have some proven models to help us in managing the process of change (e.g. force field model). We have a range of reliable and valid techniques for arriving at action plans, and for ensuring commitment to implementation (e.g. action research, survey feedback). We know about the importance of giving the ownership of change to those who have to implement it and make it work, and that this relationship is more likely to hold in certain situations than others (e.g. in Western democratic cultures). We know about the techniques which will facilitate individual and group learning (e.g. modelling). We know the key role of power in bringing about change, and hence the importance of the chief executive officer leading a major change effort.

One of the factors accounting for the limited success of many of the early OD efforts was the weak power base of the external consultant, a feature which was exacerbated by the value system of many OD consultants. Considerations of ownership and power have led many current OD interventions to become more management-centred and less consultant-centred. This is particularly noticeable in current attempts to change organisational culture.38 Consultant-driven change is more likely to occur where a packaged programme such as the managerial grid is used, or where a prestigious consultant is employed to steer through the programme. The switch to more management-driven OD recognises the source of power within the client system, the need for more flexible and less value-laden change programmes, and the fact that a key task of general managers in any organisation is managing change. For change programmes to support corporate strategy, management-driven OD is essential. This is even more so where fundamental rather than incremental change is being considered. By fundamental change one is referring to situations where an organisation re-aligns its mission and strategy to cope with new external forces. As Beckhard and Pritchard39 point out, this requires a change strategy which is built around top management’s clear vision of the end state of the whole organisation. This vision must be used to diagnose what needs to be changed, and for managing and integrating the process of change. They emphasise the importance of adopting a learning mode, where both learning and doing are valued. This learning mode is more difficult to adopt than managers think, and it is here that the special process skills of the OD consultant can play a key role.

There are clear implications here for the training of senior managers and consultants. Managers must learn to use the latter in the most appropriate way. Consultants need to be trained not only to acquire the traditional process skills of the OD practitioner, but also to have an understanding of the relationship between a business and its environment and the range of applicable solutions open to the client. Nowadays the OD consultant needs to master both process and content issues if OD is to survive as a form of consultancy which is valued by client organisations.40

5.4 References

1. Pedler M, Burgoyne J, Boydell T. The learning organisation: a strategy for sustainable development. London: McGraw-Hill, 1991.

2. Trist EL, Higgin GW, Murray H, Pollock AB. Organisational choice. London: Tavistock, 1963.

3. Burns T, Stalker G. The management of innovation. London: Tavistock, 1961.

4. Woodward J. Industrial organisation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965.

5. Lawrence PR, Lorsch LW. Developing organisations: diagnosis and action. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1969.

6. Davis LE, Cherns AB. The quality of working life. New York: Free Press, 1975.

7. ACAS QWL News and Abstract 1996; 127, Summer: 2.

8. Roethlisberger FJ, Dickson WG. Management and the worker. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 1939.

9. Lewin K. Group decision making and social change. In: Swanson GE et al. Readings in social psychology. New York: Holt, 1952.

10. Coch L, French JRP. Overcoming resistance to change. Human Relations 1948; 11: 512–532.

11. Bennis WG. Organisation development: its nature, origins and prospects. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1969.

12. Lewin K. Frontiers in group dynamics: concept, method and reality in social science; social equilibria and social change. Human Relations 1947; 1(1): 5–42.

13. Lewin K. Field theory in social science. New York: Harper and Row, 1951.

14. Jaques E. The changing culture of a factory. London: Tavistock, 1951.

15. Skinner BF. About behaviourism. New York: Vintage Books, 1976.

16. Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1986.

17. Schein EH. Process consultation: volume II. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1987.

18. Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1984.

19. Likert R. New patterns of management. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961.

20. Pedler et al. Learning organisations.

21. Senge P. The fifth discipline: the art and practice of the learning organisation. London: Century Business/Doubleday, 1990.

22. Peters TJ, Waterman RH. In search of excellence. New York: Harper and Row, 1982.

23. Williams APO, Dobson P, Walters M. Changing culture: new organisational approaches. London: Institute of Personnel Management, 2nd edition, 1993.

24. Warr P. Work, employment and mental health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

25. Buckingham GD, Jeffrey RG, Thorne BA. Job enrichment and organisational change: a study in participation at Gallaher Ltd. Aldershot: Gower, 1975.

26. Bennis. Organisation development.

27. Schein EH. Organisational psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 3rd edition, 1980.

28. Blake RR, Shepherd HA, Mouton JS. Managing intergroup conflict in industry. Houston: Gulf, 1965.

29. Blumberg A, Wiener W. One from one: facilitating organisational merger. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science 1971; 7(1): 87–102.

30. Blake RR, Mouton JS. The managerial grid. Houston: Gulf, 1964.

31. Blake RR, Mouton JS, Barnes L, Greiner L. Breakthrough in organisation development. Harvard Business Review 1964; 42(6): 133–155.

32. Hutchinson C. Organisation development in BAT Ltd In: Hacon R. Personnel and organisational effectiveness. London: McGraw-Hill, 1972.

33. Mann FC. Studying and creating change. In: Bennis WG et al. The planning of change. New York: Holt, 1961.

34. Bowers DG. OD techniques and their results in 23 organisations: the Michigan ICL study. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science 1973; 9: 21–43.

35. Clark PA. Organisational design: theory and practice. London: Tavistock, 1972.

36. Storey J. The people-management dimension in current programmes of organisational change. Employee Relations 1988; 10(6): 17–25.

37. French WL, Bell CH. Organisation development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 4th edition, 1990.

38. Williams et al. Changing culture.

39. Beckhard R, Pritchard W. Changing the essence: the art of creating and leading fundamental change in organisations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992.

40. Williams APO, Woodward S. The competitive consultant: a client-oriented approach for achieving superior performance. London: Macmillan, 1994.