6 From personal to professional development Creating space for growth

6.1 Personal development: a historical perspective

For the purposes of this chapter ‘personal’ development is taken to be synonymous with self-development1 and means that learners take the primary responsibility for choosing what, when and how to learn.2 What and how they choose to develop may or may not be related to their organisation’s needs. But organisations themselves need to understand the power and implications that accrue from personal development so that they can reap its benefits.

Self- or personal development emerged in the 1970s and 1980s as an antidote to the ‘systematic’ training approach that was adopted by the Industrial Training Boards (ITBs) (following the Industrial Training Act 1964). The rationale of ‘systematic training’ was that each organisation be required to specify the skill requirements of its workforce, identify who needed to be trained/developed to meet necessary standards, plan and implement appropriate training as required and finally evaluate whether identified needs had been met.

But while such an approach was appropriate to specific jobs where knowledge and skill could be specified, it was less easily adapted to the fields of supervisory and management development. The appearance in 1978 of Pedler, Burgoyne and Boydell’s A manager’s guide to self-developmen3 was the first of a number of works which provided companies with alternatives to the ‘systematic’ approach which was organisation-led and mediated by training officers.4,5,6 The key shift was from trainer/manager-led training to learner-led development. In the 1980s the UK government recognised the need for individual development and made funds available for the development of open learning materials which enabled individuals to choose and learn what they wanted to learn.

By the 1990s the UK government’s Investors in People scheme was going to capitalise on the development of the individual in relation to the needs of the business as a whole and although this has led to a more strategic approach to development (in contrast to the rather piecemeal way training for individual jobs was rewarded earlier by the ITBs), the focus for development is still organisation/management rather than individual-led. This highlights the differences in interpretation which persist as to the meaning of ‘personal development’ as a comparison of two journal extracts, appearing virtually concurrently has shown: Training Officer, September 1995: ‘Personal Development programmes should be inextricably linked to the needs of the organisation. No organisation can afford to waste time and resources on unfocused development.’7 Contrast this statement with the following from Personnel Today, June 1995 (quoted from Peter Heriot of Institute of Employment Studies): ‘You can no longer specifically target training and development now that organisations have fewer layers and people don’t stay long enough to target them for development.’8

These contrasting themes emerged from an Institute for Employee Studies (IES) survey of the practice of ‘personal development plans’ by eight national companies,9 the majority of whom saw ‘personal development’ in the context of an employee’s current or future job skills rather than a function of the ‘whole person’. ‘From the employee’s perspective it can be seen as a contradiction in terms to be encouraged to think about their own development in their own way but then be told to concentrate only on those needs in relation to the current job.’10 Is it reasonable that an organisation should pay for its employees to develop themselves in whatever way they like? This is a principle Tom Peters11 has long supported, in so far as, if it leads to more motivated staff who are encouraged to take responsibility for their own learning, it has got to be good for the business too. Similarly, in the UK John Harvey-Jones12 has identified the need for companies to cater for ‘people’s true inner needs which they may even be reluctant to express to themselves’.

Before examining some practical ways open to organisations to facilitate personal development, below are three principles which I would argue need to be applied if real personal development is to be promoted.

6.2 Principles underpinning personal development

Principle 1

There can be no ‘personal’ development without an individual taking ownership for his/her own development and choosing how such development will take place.

In his best-seller The seven habits of highly effective people: powerful lessons in personal change, Steven Covey throws new light on what the word ‘responsibility’ means: he suggests it literally means ‘response-ability’, i.e. the ability to be able to choose the response to make to a particular stimulus or experience.13 It is salutary, perhaps, to reflect that much of the rationale for ‘effective’ training derives from the behavioural psychology of the 1950s and early 1960s14 which sought to build a world around ‘shaping’ correct responses to given stimuli — choice didn’t come into it.

But it is also true, as the IES survey points out, that ‘taking ownership for one’s own development’ does not fit comfortably within the UK culture in that it ‘is not merely by self but also of self’.15 On the one hand, Knowles argues that all individuals are naturally self-directed learners, albeit needing help to get started16 while Abbot and Dahmus17 are of the view that individuals will vary as to their ‘preparedness’ for self-directed learning. But either way the individual is the only person who can take responsibility for his/her learning — however it occurs.

Over the last decade there has been increasing interest by companies in ‘personal development plans’ but these very often are seen as but an extension to the training plan whereby an individual’s ‘personal’ needs are as prescribed by others as is the training programme to meet the company’s objectives,18 or they are an add-on at the foot of the appraisal form with little time given by the appraiser to address them.19 A personal development plan must start and finish with the individual.

Another recent trend has been increasing recognition of learning from experience and accreditation of prior learning (APL).20,21 These initiatives have moved the focus of attention away from the trainer and the company towards an individual’s own experience and the learning derived from that. However, when assessing APL, all too often the main attention is given to the evidence of the experience itself rather than the learning derived from it and where that leads.

Huxley (quoted in Pye)22 maintained that ‘experience is not what happens to a man, it is what a man does with what happens to him’. Pye makes the point that learning is an active and essentially integrative process continually trying to make sense of experiences in a context within which the learner is both patient and agent. While we tend to think of reflection as a very individual and private process, the fact is that reflection only makes sense with reference to action or context which is located at a time in history. Thus, reflection is a social process. This takes us on to principle 2.

Principle 2

If learning is a ‘social’ process, individual and personal development plans can only be realised in and through developing with others.

the individual is necessarily enmeshed in a world of others. The eternal dilemma for individuals is that, once they embark upon social relationships, this very act demands the surrender of their individuality — to some degree.23

The paradox here is that ‘Persons can only be persons in relation’.24 Heron goes on to say:

Following the path of self-development is not simply to take an inward turning, it is to go in and to go out. The clear implication is that an organisation will not be responsive, innovatory and self-renewing on the outside unless we are able to nurture and release the energy of those on the inside. This is the vision of the learning organisation.

Unfortunately it is a vision that few organisations which aspire to be ‘learning organisations’ have fully realised. Most have the right intentions — to provide the necessary support and resources to ‘facilitate’ individual development — but what they fail to do is to become fully enmeshed in and identified with the kind of development they seek to promote. Adlam and Plumridge25 sought to simulate just how an organisation might come to terms with ‘self-developers’. At a conference on self-development they created two groups: one group was encouraged to focus on issues of self-development while the other was to consider itself as the parent organisation who had to find ways to accommodate and support the self-development group. Though they devised appropriate strategies of support, nothing prepared them for the reality of coming to terms with the very personal nature of the experiences the self-development group enjoyed. This led them to this basic premise: ‘Unless those responsible for supporting the growth and development of others in the organisation are themselves actively engaged in their own self-development, they cannot actually tune in to the quality of the experiences of self-developing others.’ Organisations trying to come to terms with the dilemma between supporting individual development (in whatever direction that might lie) and development to achieve corporate goals might well reflect upon the following:

It is in the very act of trying to help others that we are likely to be allowed a sense of their inner selves — of their thoughts, values and feelings; and that process unlocks for us many insights into our own selves … This opening of others to self and self to others is a perquisite for reciprocal behaviour and therefore the foundation stone of our own growth and development. Opportunities for such behaviour are constantly with us if we choose to take them.

This leads on to principle 3.

Principle 3

In opening up our own development to and with others a reciprocal process takes over whereby others are drawn to us in ways we had not previously anticipated.

Not so many years ago such a notion might have been thought to border on the mystical but in the 1990s what Jung called ‘Synchronicity’26 appears as a central theme in a range of works both populist27 and of the more ‘management guru’ kind.28,29 Covey observes:

the more authentic you become, the more genuine in your experience, particularly regarding personal experiences and even self-doubts, the more people can relate to your experience and the safer it makes them feel to express themselves. That expressing in terms in turn feeds back on the other person’s spirit and genuine creative empathy takes place, producing new insights and learnings and a sense of excitement and adventure that keeps the process going.

Such a sentiment is not new. It is embedded in existentialist philosophy and psychology30,31 but though ‘tacitly’ understood it has not really been translated into best practice. Carl Rogers tried to break the mould in 1969 with the publication of Freedom to Learn32 and in 1987 Roger Harrison took a great risk (for the time) by publishing a paper sub-titled ‘a strategy for releasing love in the workplace’.33

The current preoccupation with the concept of an organisation as a learning organisation might be thought to provide a context for such a principle to be put to the test but there is little evidence of this happening. I would argue that the main reason is that in seeking to envisage and espouse something ‘out there’ called a learning organisation we have lost sight of what, at heart, an organisation actually is — relationships between individuals. If, as we have suggested, personal development can only take place in relationship with others might this not be a start on the learning organisation journey?

6.3 Translating principles into practice

A personal development plan for all

The starting point must be for each individual to put together their own personal development plan which needs to cover:

1. Goals and aspirations.

2. An indication of resources/methods/support needed to achieve these goals.

3. An indication of a time in the future when the goals will be realised.

4. An indication of how these goals will be recognised by others.

Though organisations tend to reserve PDPs for managers and high-flyers, David Clutterbuck makes the point that there should be ‘a personal development plan for every citizen’34 which should include goals and achievement that are not confined to the workplace but encompass domestic, leisure, sport, community and long-term career prospects.

It is also in keeping with what has been called ‘organisational citizenship behaviour’35 which draws attention to the breakdown of the ‘normal contractual relationship between employer and employee’. In its place they suggest the growth of a ‘covenantal relationship which is characterised by open-ended commitment, mutual trust and shared values’. Perhaps this is the ‘new bonding agent’ Simon Caulkin is seeking:

Put brutally, individuals are asking themselves: if the company no longer represents a career, a pension or a ‘safe job’ what am I doing here? If the organisation can’t provide a satisfactory answer to this existential question – if it hasn’t found a new bonding agent to replace the deferred gratification of the next job or a secure old age … it will fall apart at the first touch of pressure.36

Caulkin envisages a new kind of organisation called ‘ME plc’ where ‘the workers’ take control of all that is left to them to control – their own development. He quotes Robin Linnecar, partner at KPMG Career Consultancy: ‘The only way to keep them [employees] is to risk losing them. You have to give them more room to develop, which at the same time makes them more marketable. But, ironically, that’s how you create loyalty’.

A question for managers to address, then, is what scope can they give every employee to develop themselves in whatever way they choose? There is a tendency for many PDPs to be too narrowly focused, reinforced by a work ethic which is reflected in the way they are encouraged to think that ‘personal’ relates to personal behaviour in the workplace. If we are really serious about expanding individuals’ horizons in the hope that they may contribute to expanding an organisation’s horizons too (at least while they are still employed there), we must encourage employees to ‘dig deeper’: ‘Our task is to encourage people to think as widely as possible about their attributes’.37 One way of doing this is through the creation of a ‘personal portfolio’.

Portfolios for development

As we shall see when we review trends in professional development, the use of the portfolio as a vehicle for recording evidence of an individual’s continuing professional development (CPD) has become widespread. But in my experience there is often an underlying assumption that putting together a portfolio is simply a matter of following a few guidelines. In my work with healthcare practitioners,38 despite there being a number of ‘do-it-yourself’ portfolios on the market, they were unable to answer two fundamental questions: why am I putting together this portfolio and where do I start?

Besides being used for charting professional development, the portfolio is also a useful vehicle for exploring one’s personal development. But where do you start? Warren Redman has a very useful five-stage approach to building up a portfolio starting with the creation of what he calls ‘The Index’.39 ‘The aim of this is to begin to establish the range of experiences that a person has … These are brief reminders of a whole range of things that someone has done, or events that have taken place that have some significance for the portfolio-builder.’ This is a different approach from the usual one of starting by encouraging an individual to identify their strengths and weaknesses. Redman suggests that it is often difficult for individuals to look objectively at their strengths and weaknesses and suggests we take a more ‘neutral’ approach by enabling them to focus on their ‘experience before we can usefully get them to recognise what their qualities are’.

By first jotting down three or four significant experiences (e.g. ‘the birth of my son’, ‘being made redundant’, ‘running a training course for trainers’), Redman argues that an individual can get ‘some insights into their own abilities and how they can extend themselves’. The next part of this first stage is to take each experience and describe what happened, to tell a story. Various other techniques can help an individual focus on significant areas of life’s experiences which can be a basis for a portfolio’s ‘index’: producing a biography; charting ups and downs on a ‘lifeline’; domain mapping; repertory grid.40,41 Stage two is to discover what is to be learned from this experience. Redman suggests that this be done in conjunction with others. Again, the summary should be written down. Stage three is at the heart of the portfolio: producing evidence of what was learned from the experiences described. Evidence may be in the form of photos, certificates, letters, reports, notes, designs. Producing evidence is a critical part in anyone’s personal development as it externalises an internal process to enable it to be recognised and corroborated by others.42 Thus our perception of ourselves is reinforced by the way others see us.

In many schemes of accreditation of prior learning and certainly in so far as assessment of National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs) is concerned, stage three must be the ultimate aim of the portfolio – to produce evidence able to be assessed by others in recognition of a claim for accreditation against vocational, academic or professional standards. But Redman adds two other steps to justify his claim that portfolios can be used for development purposes as well as vehicles for accreditation. Having derived learning from a particular experience and provided evidence of this, stage four asks, ‘What do I still need to improve in this area?’ Redman describes it as taking ownership for development needs for the future. Finally, stage five brings us back to the personal development plan. First, what action am I going to take to improve in the way I have identified in stage four and what resources and support will I need to do it and by when? Second, stage five reviews whether ‘I have taken up the learning opportunities identified’ and asks what has been the outcome/consequence of that learning. It follows that this might lead on to another cycle of development.

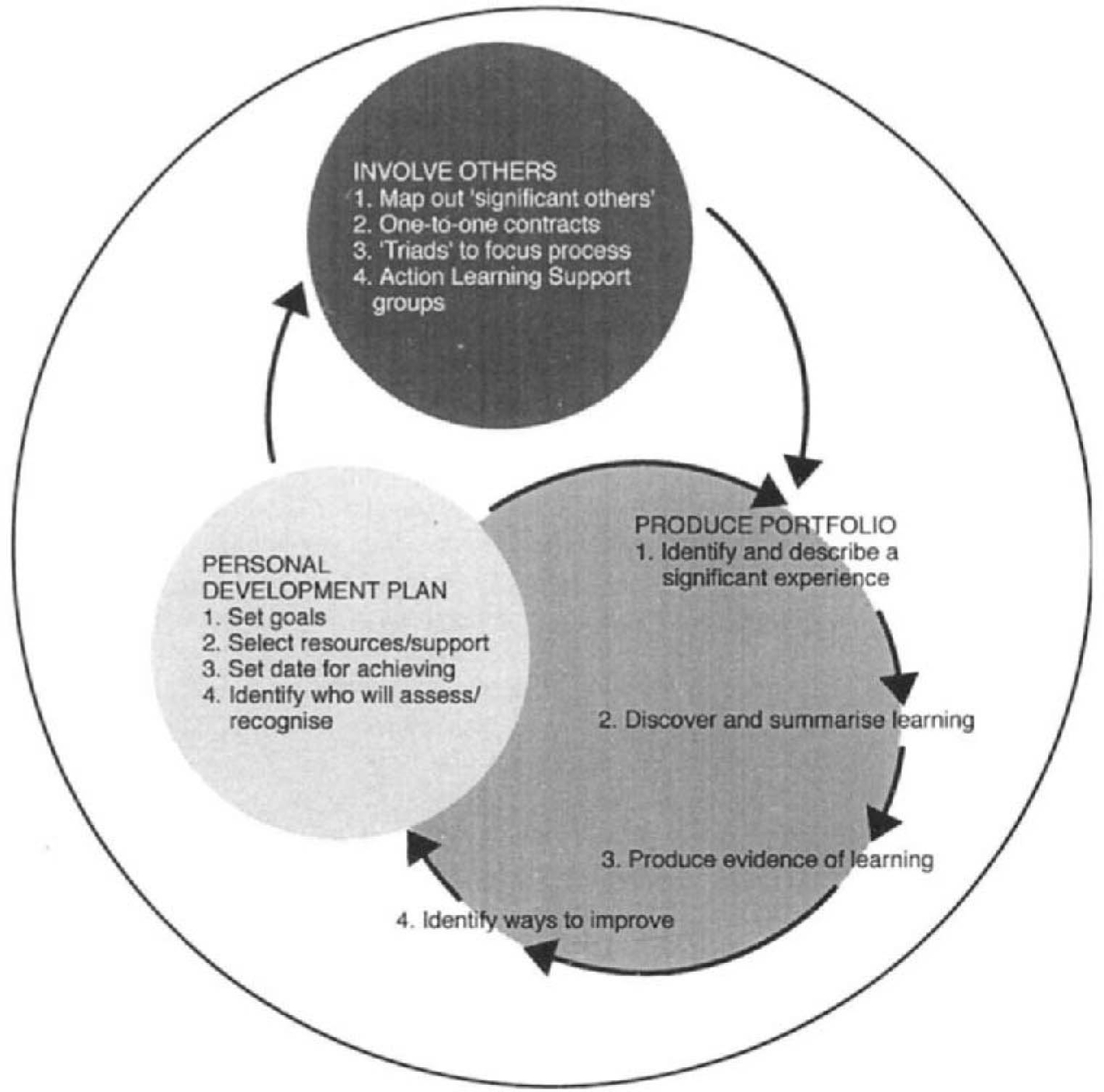

Although I have suggested that the production of a PDP is the starting point, others have recognised the need to help individuals ‘engage’ in a personal planning process which the creation of a portfolio in the way Redman describes helps to facilitate. We can summarise the two stages so far identified in helping individuals’ personal development as two interlinking routes the starting point for which could either be a PDP or a portfolio, as shown in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 Stage 1 of a personal development plan

Involving others

Principle 2 stated that learning is a social process and that individual and personal development plans can only be realised in and through developing with others. Thus the development manager has a role in trying to help individuals create the kind of support network around them which will not only help them develop but will also enable others to develop with them. Personal development has to be part of reciprocal relationships. ‘Persons can only be persons in relation’.43

But just as it is not always easy to sit down and produce a personal development plan without going through some of the exercises we have explored, so it is advisable that individuals first do some personal reflections about the kind of people who have influenced them in the past so that they can better identify the kind of person who will be helpful in the future. A simple way of doing this is to put oneself in a circle in the middle of a page and then identify ‘significant’ other people that have been of help to you in the past and the present: e.g. your partner; particular colleagues; tutor on a training programme, etc.

The next stage is to identify who can help with what. A useful way of doing this is to select the objective to be worked on, list appropriate individuals on the left and the kind of help/support being sought on the right. Here’s an example:

| OBJECTIVE: | To have submitted and had approved budget by end of financial year |

| WHO CAN HELP | HOW |

| Mary from Central Services | By installing new spreadsheet package and coaching me until I can produce report from input data |

| Tom in Accounts | By giving me feedback on first draft |

Finally, negotiate with each person and perhaps arrive at individual learning contracts. Some people may be able to act as mentors.44 But colleagues can support other colleagues in a variety of ways. The aim is to encourage dialogue and ‘learning conversations’.45 Individuals can come together on a regular basis for no other purpose than to support each other’s development. But there must be clear objectives which each person is trying to achieve — so individual PDPs would be useful data on which the group can plan how to help one another.

Depending on just how task or process oriented the group is, it could be classified as a learning support group or an action learning group. Action learning has received considerable attention in recent years, mainly in relation to management training, 40 years after its founder Reg Revans first introduced the idea of building up a degree of trust between a group of professionals, each of whom wished to solve particular problems. The idea was that the group encouraged each person to articulate their problem and take on board comments and criticism from the others before committing themselves to action which would then be reviewed at the next meeting.46,47

Support groups of this kind usually begin by drawing up ground rules to govern the way they will work with each other. Some commonly accepted principles underpinning action learning are:

• respect for each other;

• trust in each other;

• non-competitive;

• take risks;

• confidentiality;

• listen and give full attention;

• say what you feel;

• value each other’s contribution;

• all members to participate;

• be honest;

• don’t interrupt;

• feel free to challenge.

Such groups are ideal for self-development because there is no formal theory or content to shape their course. They exist solely to help individuals achieve their task and in the process become aware of the learning needed to fulfil the task.

We can now add the various ways of ‘involving others’ to the first two ways of going about self-development. It provides a third route which can start with the PDP and be reflected upon in the portfolio (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Stage 2 of a personal development plan

6.4 Professional development – a historical perspective

Having sought to explore reasons for managers to promote personal development — not least because of the consequences for interpersonal as well as organisational learning, we now turn to what might be thought a safer area, professional development. This is a typical dictionary definition of ‘profession’: ‘A vocation or calling, especially one that involves some branch of advanced learning or science (the medical profession).’48

The Standard Occupational Classification regards a professional as someone with a degree and post-graduate qualification.49 Defined thus, ‘professionals’ would currently represent about 15 per cent of the workforce. By the end of the decade it has been estimated there will be over 10 million people classified as managers, professionals or associate professional, and involved in knowledge-intensive work and requiring a high level of education and continual professional development throughout their careers.

In recent years most professional bodies have recognised that merely ‘having’ qualified at a given time to meet the knowledge requirements imposed by a profession is not sufficient for a practising professional in a constantly changing world. Hence the emphasis on CPD — continuous professional development — whereby each profession requires its members to demonstrate that they have kept themselves abreast of changing theory and practice.50 Unless a member seeks upgrading of membership it is difficult to monitor the success of such a policy but at least it is becoming a recognised policy. More and more professions are providing their members with the means of recording such development (e.g. Institute of Personnel & Development 1995; Institute of Management 1996) as evidence of their CPD.

Implicit in the Standard Occupational Classification definition of ‘professionalism’ is that a professional will have not only a first degree but also a post-graduate qualification (appropriate to a particular profession’s domain of knowledge/expertise). Therefore ‘professionalism’ implies a degree of academic ability being recognised. This is in contrast to the notion of ‘vocational’ competence which seems to be aligned with a perception of a level of skill that falls below that of professional. This perception has done much to colour the debate about another UK government initiative, the establishment of NVQs. Is there a way of bridging this divide?

To find out, we need to understand a little more about the nature of professional knowledge and the context within which it can be acquired. As in the first section, we will explore three principles we believe underpin the nature of ‘professionalism’ and then suggest a framework within which such principles can be put into practice, building on the guidelines already proposed for facilitating personal development.

6.5 Principles underpinning professional development

Principle 1

The professional is continually developing his/her practice by reflecting on experience of new and changing contexts.

There is a paradox here which Richard Winter explores.51 On the one hand, just what the professional does may be difficult to verbalise but, on the other hand, unless the process is made explicit in some way, how can the professional and other professionals learn?

Donald Schon has done much to focus attention of academics and managers alike on the way professional people actually learn to become professional.52,53 He contrasts the way colleges ‘teach’ would-be professionals against ‘validated’ rules with the way the professional learns his/her trade in practice, building up a ‘repertoire’ of past examples as precedents to deal with any particular situation. In this sense the would-be professional draws as much upon intuition as to what feels right in a particular context. In examining how architects, musicians, psychoanalysts and counsellors learn their profession Schon feels that the context in which they learn is more akin to a ‘studio’ than a classroom.54 He sees two processes at work: ‘knowing-in-action’ and ‘reflection-in-action’. ‘Knowing-in-action’ would describe the knowledge implicit in being able to carry out some skilled performance (e.g. driving a car; carrying out an operation) but which the professional wouldn’t normally be able to ‘verbalise’ at the time: ‘The knowing is in the action’.55

Schon would argue that we are unable to explain what it is we are doing or why we do it until something happens to make us question and reflect on what we are doing. This could be as the result of a surprise remark, action or error or somebody simply asking ‘Why?’ or ‘What if?’. This leads to what he calls ‘reflection-in-action’: ‘the rethinking of some part of our knowing-in-action leads to on-the-spot experimentation and further thinking that affects what we do in the situation at hand and perhaps also in others we shall see as similar to it’.56 It is this ‘iterative’ process of engaging in a dialectical process of learning which characterises the nature of professional ‘knowing’ as we build up a body of knowledge appropriate in a particular context. Winter produces a list of ten propositions which together form ‘a unified process linking professional practice, knowledge, understanding, skill, commitments and self-knowledge’ which I would suggest provide a useful framework within which managers can recognise and actively promote professional development.57 These ten propositions on the nature of professional work are reproduced below:

1. The nature of professional work is that situations are unique, and knowledge of these situations is therefore never complete.

2. It follows that, for professional workers, a given state of reflective understanding will be transformed by further experience of practice.

3. Professionals will draw upon a repertoire of knowledge derived from comparison of a multitude of different contexts and the way their practice has changed.

An implication that follows from such principles is that, regardless of whether a manager has or has not got a particular management qualification, for example, there should be something new for him/her to learn from every situation involving management decisions and judgements. How are your managers or any other ‘professional’ encouraged to ‘reflect’ on their practice and record such ‘continuing development’?

4. Professional work involves commitment to a specific set of moral purposes, and professional workers will recognise the inevitably complex and serious responsibilities which arise when attempting to apply ethical problems to particular situations.

5. The responsibility for equitable practice which characterises the professional’s role commits professional workers to the comprehensive, consistent, conscious, and effective implementation of ‘anti-oppressive’ non-discriminatory principles and practices.

This has particular implications for managers responsible for the development of all their staff, some of whom may seek development which you, as their manager, consider inappropriate. How do you help managers come to terms with such decisions and how can they be helped to learn from them?

6. Authoritative involvement in the problem areas of clients’ lives inevitably creates a complex emotional dimension to professional work, and professional workers therefore recognise that the role involves understanding and managing the emotional dimension of professional relationships.

7. Consequently, professional workers recognise that the understanding of others (on which their interpersonal effectiveness depends) is inseparable from self-knowledge, and consequently entails a sustained process of self-evaluation.

Again, what support do you give to managers, fellow professionals, to cope with situations in which they have become ‘personally engaged’? How do you help them to use the situation (for example, having to break the news to someone that they have been made redundant) to enhance their own learning?

8. The incompleteness of professional knowledge (see l. and 2.) implies that the authoritative basis of judgements will always remain open to question. Hence, for professional workers, relationships with others will necessarily be collaborative rather than hierarchical.

9. Professional workers will be aware of available codified knowledge — e.g. concerning legal provisions, organisational procedures, resources and research findings — but they will recognise that the relevance of the knowledge for particular situations always depends on their own selection and interpretation.

Underpinning both of these principles is the recognition that, contrary to what the text books may say, there are no right, absolute answers to all situations. The professional has to look at each situation differently although it is the hallmark of professionalism that the professional draws on his/her experience to make the most appropriate decision in a given context. Again, how are your staff encouraged to identify such situations and learn from them?

10. The process of analytical understanding which professional workers will bring to their practice involves creative tension between making sense of different contexts, synthesis of varied experiences into a ‘unified overall pattern’, ability to relate a situation to its context, understanding of a situation in terms of its tensions and contradictions.

Common to all of these skills is the capacity to make sense of a variety of changing and often conflicting situations.

I wonder how many professional bodies take these propositions into account in their recommendations for CPD. The emphasis has tended to be on what Winter calls ‘codified knowledge’ rather than on ‘the relevance of the knowledge for particular situations’ which will always depend on the manager’s ‘own selection and interpretation’. Hartog used the same argument to comment on IPD’s modular professional education scheme.58 She argues that there isn’t sufficient scope for developing individuals’ ‘capability’ which can only come from some kind of ‘Action Learning’ in the company of fellow professionals. Similar views about the need for ‘reflection-in-action’ have been put forward to develop professional practice amongst teachers59 and physiotherapists.60

This brings us to a key criterion of ‘professionalism’ which underpins Principle 2.

Principle 2

To be recognised as ‘having’ professional expertise requires that one’s knowledge and competence are recognised by others themselves recognised to be professionals in a particular context.

‘A professional’s knowing-in-action is embedded in the socially and institutionally structured context shared by a community of practitioners.’61 It is the ‘context shared by a community of practitioners’ which is at the core of professional knowledge and an area where managers can play a key role in helping create the kinds of networks in which professionalism can be nurtured. In a previous work Schon referred to this as ‘public knowing’62 but it is also a form of ‘public testing’. Only when you are prepared to test out your ideas and have them validated (or refuted) by the wider ‘academic’ community can you be said to be a professional researcher, for example. Again, it is the professional context which gives your work meaning.

In the final principle we examine the nature of ‘transferability’ of the core knowledge and experience which underpin all professional activity irrespective of context.

Principle 3

Underpinning professional competence are a core set of values which, whilst being needed to demonstrate professional competence in a particular context, have universality of application wherever professionalism is required.

The paradox is that, on the one hand, professional evidence needs to be related to a particular context from and within which it is given credibility and validated but, on the other hand, the professional learning derived from that evidence goes beyond the present and has a universality, the essence of which can be transferred to other situations.

This was a basic principle which led Richard Winter to evolve what he calls a ‘general model for practice-based professional education’63 in what is known as the ASSET programme (Accreditation for Social Services Experience and Training). This was a programme which resulted from a collaboration between Anglia Polytechnic University and Essex Social Services Department to provide a qualification for social workers which reflected both academic standards (through getting a degree through Anglia) and professional standards as recognised by the Central Council for Education and Training in Social Work (CCETSW) (now replaced by the Social Care Council).

The model developed was based on the evolution of competences through the NVQ-preferred route of functional analysis. This involves starting with the ‘purpose’ of an occupation and continually asking the question ‘What needs to happen for this purpose to be achieved?’ For a full explanation of the role of functional analysis in the development of NVQs, see Mansfield and Mitchell.64 But Winter felt that the normal process of assessment against performance criteria of separate elements did not reflect the ‘holistic’ way that professionals worked; nor did it meet the kind of criteria we have examined under Principle 1. Winter therefore decided to arrive at a set of what he called ‘Core Assessment Criteria’ which social workers used in judging qualities of their professional colleagues.

As a result, seven additional criteria were derived:

1. commitment to professional values;

2. continuous professional learning;

3. affective awareness;

4. effective communication;

5. executive effectiveness;

6. effective grasp of a wide range of professional knowledge;

7. intellectual flexibility.

In demonstrating their competence, social workers had to show evidence of their meeting each of the competences (as they would under any NVQ assessment) but, in addition, they had to choose one core competence and show how their evidence met that criteria also.

As Winter acknowledges, his model is not the only one to be concerned about the emphasis on ‘lists of specific behaviour’ rather than taking a more ‘holistic’ approach to assessment of underpinning core values. The Management Charter Initiative (MCI)’s management standards, for example, have a ‘Personal Competence Model’ over and above the functional units, which covers processes of ‘optimising results’ by planning, managing others and managing oneself, and ‘using intellect’. But because they are a separate unit they are not automatically integrated within the assessment process though assessors are required to take account of them. This has led to calls for their integration.65

The Care Sector Consortium’s standards for care include what they call a ‘Value Base Unit’ which are the basic standards of good practice which all healthcare practitioners should observe in their professional work: e.g. anti-discriminatory practice, confidentiality of information, individual rights and choice, etc. But again, though assessors are reminded of appropriate values to be taken into account in assessment of each element, Winter’s point is that no other scheme has made assessment of core values such an integral feature to the extent that they provide a framework within which evidence is selected in the first place.

It is perhaps ironic that although NVQ standards are presented as long lists of performance criteria against each of which a candidate has to provide evidence in practice (as anyone who has assessed NVQs would confirm), an assessment is made of overall performance using the criteria as exemplars of the kind of behaviour the assessor should be looking for.

We have covered a wide range of theoretical principles in this chapter. At the beginning of the chapter we speculated about how to bridge the divide between what is perceived as vocational and what is perceived as professional. To illustrate just how the three principles we have discussed might help managers do just this, I include an example based on a manager helping colleagues better manage their teams.

Let us suppose you are asked to help a manager develop their team of staff. A starting point might be using the Management Charter Initiative’s NVQ accredited standards for managers, a unit of which focuses on how to ‘Develop and improve teams through planning and activities’. This specifies separate ‘performance criteria’ against which managers would be required to demonstrate competence at being able to develop their team. Equally, you may have your own company criteria for team development. Either way there are criteria against which competence can be assessed.

But Winter would argue that ‘professionalism’ is more than meeting pre-designated criteria. Using the three principles we’ve introduced we can see ways in which professionalism might be developed and accredited.

According to Principle 1, professionals develop and refine their expertise in a range of situations from each of which they would be expected to learn and review their practice (‘reflection-in-action’). You might therefore require your managers to keep a log of situations where they contributed to their team’s development and how reflection on what they achieved has informed their practice. Furthermore, taking account of Winter’s ten propositions characterising professional work, you might also want them to identify particular situations where they have had to cope with ethical and personal dilemmas (e.g. having to negotiate with a group to ‘include’ a member of staff they are seeking to ‘exclude’).

According to Principle 2 there is a requirement that their professional behaviour is recognised by other professionals. Thus you might stipulate that the achievement of your managers in developing their respective teams is recognised by other managers in other departments and by the HRM department.

Finally, according to Principle 3 you might want to check out the extent to which skills in one situation can be transferred to others. For example, ‘affective awareness’ was one of the core professional competences Winter identified. What evidence is there of your manager being able to ‘empathise’ with others — a quality which should be evident to staff in his own team but which also becomes a part of his ‘professional’ behaviour which is demonstrated in a variety of contexts?

I hope this gives you a feel for how professionalism can be fostered amongst your staff. Now let’s look at some other practical ways of putting these principles into practice.

6.6 Translating principles into practice

Creating professional groups

A key principle for professional development is that professionalism is not just about acquiring what Winter calls ‘codified knowledge’ but depends on ‘refiection-in-action’ in the company of other professionals. What role, if any, has a manager in facilitating such a process?

In the first section we argued that helping individuals to become aware of and take ownership of their personal development can create a different kind of trust between employees and the organisation which goes far beyond the job for which they are employed. Though there is a risk – as there is with any form of development — that individuals will take their new knowledge and expertise elsewhere, the very engagement in such a process cannot but add value not only to the individual but to the organisation as a whole because, if the development takes place at work, the individual’s development must take place in an organisational context. It is up to the organisation if it chooses to see personal development as an altruistic act or as adding value to the organisation as a whole.

If investment in personal development is a risk which may be difficult to evaluate at the level of the organisation, then investment in professional development has a more immediate pay-off. But, I would argue, you cannot have one without the other.

In personal development the individual is primarily learning from and with others for their own development. In professional development the individual is also learning from and with others but this time is able to give something back such that the professional group and wider community as a whole benefit. Once we see professional work as going beyond the traditionally recognised boundaries set within ‘codified knowledge’, we are in a position to explore new connections between an individual’s work and contribution to the organisation as a whole.

Within the ten propositions there are five key themes which, I would suggest, give us a clue as to how to recognise professional work when we see it. The same principles could be used to create professional groups within the organisation. Work that is professional will demonstrate the following characteristics:

1. It will involve a unique situation in which knowledge within a group is pooled but recognised as incomplete and requiring the collaboration of the whole group.

2. Through a process of reflection relating to the issue/problem under review the group arrives at an extension of/addition to the knowledge it possesses.

3. The group recognises the responsibilities and rights of all parties involved.

4. The group is sensitive to and able to manage inherent contradictions and tension in the situation and emotional consequences.

5. The group possesses recognised knowledge and expertise which members are able to draw from a wide range of separate experiences.

Put thus, you might well wonder if a Quality Control Group, a Learning Support Group or an Action Learning Group might not be considered to be a ‘professional group’. The answer is undoubtedly yes, if it can be seen to meet the above criteria. Professional development in the past has been too much focused on ‘content’ (codified knowledge) rather than the context within which that codified knowledge can be given shape.

One way of changing the balance would be for development managers to recognise what groupings potentially could give rise to such work. It is likely that in the majority of organisations work is organised according to functions and accountability largely within a hierarchical framework. Suppose now that you were to create alternative groupings which are built around individuals’ contributions to an organisation’s objectives. It is likely that the nature of an organisation’s business will determine the kind of professional development it would seek to encourage. Thus, a marketing company would be likely to encourage CPD leading to membership of the Institute of Marketing, an engineering company would look to accreditation of professional engineers. It is also likely that such professional routes would only be open to employees with appropriate technical background who have appropriate jobs and positions in the hierarchy within which such knowledge can be applied and developed.

Thus the proper CPD route for a Sales Manager might be to get accreditation for a management competence and/or recognition through the Institute of Marketing. On the other hand, an employee who merely ‘sells’ to the public (either a retail assistant in a shop or a catering assistant serving up chips in the company’s restaurant) is unlikely to be a member of a professional group designated as ‘selling’. If they do get development it is more likely to be seen to be ‘vocational’, an NVQ level 1 or 2, for example. But may they not also be considered ‘professional’ according to the criteria listed above and be developed as such? We would argue that the route from vocational to professional is a function of being recognised as having a contribution to make which is recognised within a group of professionals.

So, when the chef leaves his kitchen he leaves his ‘whites’ behind, dons a suit and joins a group of fellow professionals who are not discussing menus but company-wide services. The technical assistant leaves her workshop and joins a professional group exploring new ways of improving manufacturing design. The ‘secretary’ switches off his PC and joins fellow professionals to help design a company-wide communication system.

I suggest that every employee in any organisation could become a member of a ‘professional’ group which cuts right across the job they happen to be in at any one time. Despite attempts to create the ‘flexible firm’ and ‘organic networks’,66 most organisations reflect principles of management and control appropriate to a different age.67 My suggestion is that development managers have a role in not just encouraging CPD within the familiar professional groupings (Accounting, Marketing, Personnel, etc.) but across vocational boundaries so that everyone can work towards a profession, even when the jobs they were trained for no longer exist.

Creating a context within which professionalism can grow in the company of other professionals is the first step. The next step is to ensure that the group engages in what Schon calls ‘reflection-in-action’ in such a way that reflection on practice leads not only to improved practice but genuinely new knowledge which both adds value to the organisation and can potentially contribute to the profession as well.

Facilitating ‘reflection-in-action’ that leads to new knowledge

In his book Portfolios for development Redman has chapters on the use of portfolios for both team development and for organisation development.68 In the latter case he reports on work carried out at Sutcliffe Catering in which I was also involved. The objective was to ‘create a culture of learning within one particular profit centre’ involving all 1000 staff.

To do this we designed a portfolio in which everyone, from the Operations Director down to catering assistants, was asked to record evidence of learning from a customer. As Sutcliffe was a ‘Service’ business it was thought appropriate to use this as the focus for learning. But in order to demonstrate how individual learning could be picked up by respective groups in the hierarchy, individual employees were encouraged to share their learning with colleagues at a number of levels: unit level staff shared with each other and their manager who in turn took ideas on to a meeting of unit managers chaired by an Area Manager (as well as sharing his/her own learning). The Area Catering Supervisor then reported upwards, and so on.

In retrospect, the aim of ‘creating a learning culture’ by this means was extremely optimistic69,70 but the method of using a portfolio to record not just individual learning but also group learning, I suggest, can be used to help groups of professionals (as described above) collect and have their own learning corroborated.

In the Sutcliffe project each individual was asked to identify what it was that others could learn from what he/she had learned. This is what was shared with the work group. The group then commented on the outcome, as a result of which an original idea was likely to be modified in some way, leading to the building up of new knowledge which the group as a whole could own and take responsibility for developing further. In this way what may have begun as personal development can become the basis for professional development depending on the group involved (see Principle 1) and extent to which the group engages in reflection-in-action which in turn leads to new knowledge (Principle 2).

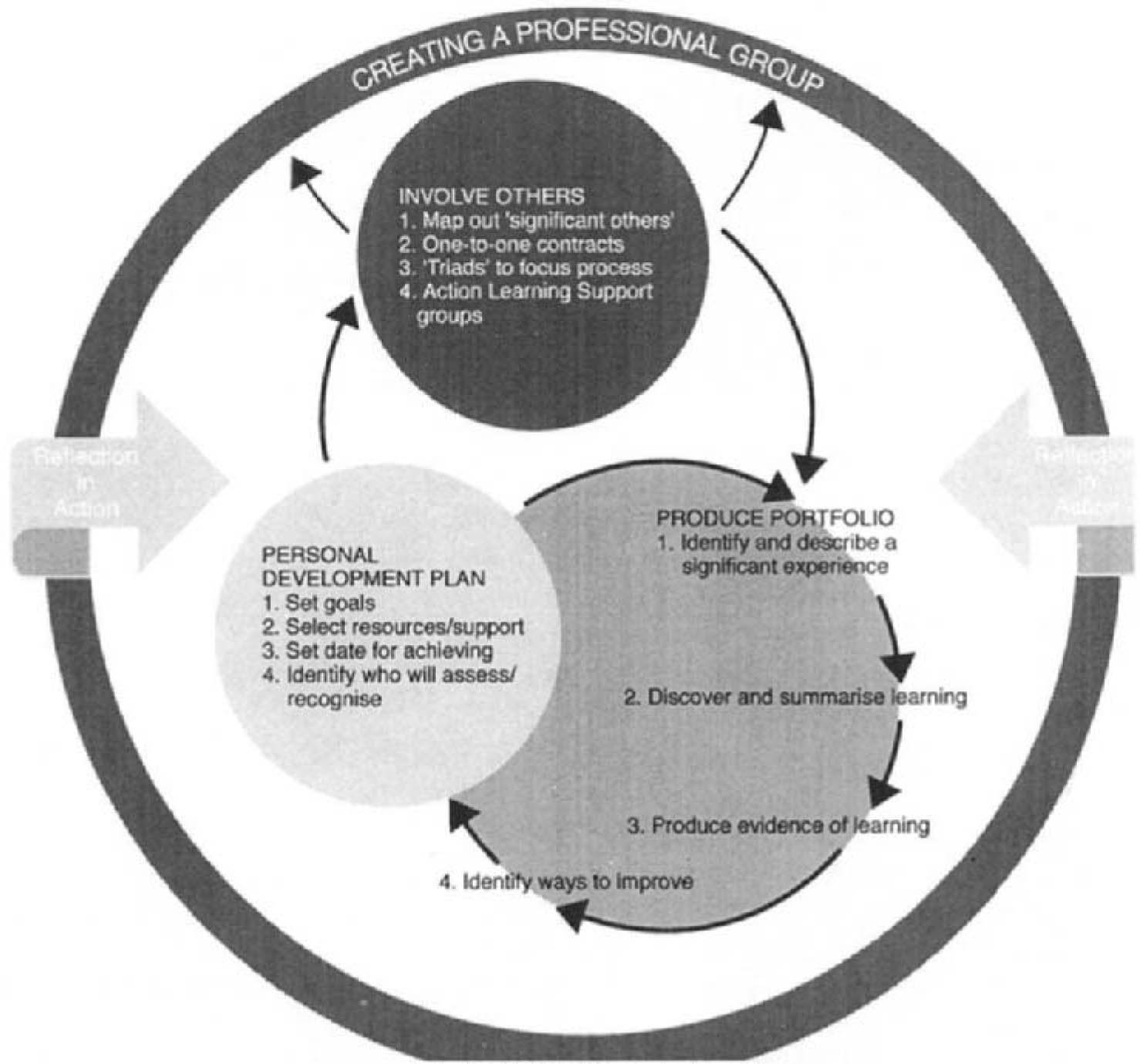

So, a lesson for the development manager might be that it is not enough to create a professional grouping in the way suggested above; the group must also be seen to be ‘reflecting’ on their practice in such a way that the outcome can in some way add knowledge to the organisational bank. We can now add this dimension to our model (see Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3 Stage 3 of a personal development plan

6.7 Conclusions

In this chapter I have suggested some ways in which development managers can help facilitate the process of personal development. I have argued that by taking care of personal and professional development the conditions are created whereby learning can be recognised and facilitated that will lead not only to a learning organisation but to a learning society. By following the kinds of practice suggested in this chapter, the development manager will be helping employees of the future adjust to a different view of their jobs, their career and their development which is well expressed in this final extract:

Perhaps we need to develop a new orientation, a new psychology of aspiration that fits better with the harsher, more competitive conditions. Rather than assuming each new job is ours until we choose to leave it, we should assume it is temporary until it proves permanent. Rather than assuming a lifetime of corporate ascent we should seek a lifetime of interesting experiences. Rather than planning personal development in relation to a defined coherent career path, we should perhaps ensure we remain flexible and develop skills and abilities in relation to the best map we can draw of society’s future rather than follow an extrapolation of our own past.71

6.8 References

1. Pedler M, Boydell T. Managing yourself. London: Collins, 1985.

2. Megginson D, Pedler M. Self-development: a practitioner’s guide. London: Kogan Page, 1992.

3. Pedler M, Burgoyne J, Boydell T. A manager’s guide to self-development. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1986.

4. Pedler, Boydell, Managing yourself.

5. Reeves T. Managing effectively: developing yourself through experience. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1994.

6. Anderson A, Barker D, Critten P. Effective self-development: a skills and activity-based approach. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

7. Young C. Personal development: part of a happy family. Training Officer 1995; September: 202–203.

8. Hagerty S. Self-service Personnel Today 1995; 6 June: 25–6.

9. Tamkin P, Barber L, Hirsch W. Personal development plans: case studies of practice. London: Institute for Employee Studies, 1995.

10. Tamkin et al., Personal development plans.

11. Peters T. Thriving on chaos. New York: AA Knopf, 1987.

12. Harvey-Jones J. Making it happen. London: Pan, 1989.

13. Covey S. The seven habits of highly effective people: powerful lessons in personal change. London: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

14. Skinner BF. Analysis of behaviour. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961.

15. Tamkin et al. Personal development plans.

16. Knowles M. The adult learner: a neglected species. London: Gulf, 1978.

17. Abbott J, Dahmus S. Assessing the appropriateness of self-managed learning. Journal of Management Development (UK) 1992; 11(192): 50–60.

18. Young, Personal development.

19. Tamkin et al. Personal development plans.

20. Kolb D. Experiential learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1984.

21. Simosko S. APL (Accreditation of Prior Learning): a practical guide for professionals. London: Kogan Page, 1991.

22. Pye A. Past, present and possibility — an integrative appreciation of learning from experience. Management Learning 1994; 25(1): 155–173.

23. Adlam R, Plumridge M. Organisational effectiveness and self-development: the essential tension. In Pedler M, Burgoyne J, Boydell T, Welshman G eds. Self-development in organisations. London: McGraw-Hill, 1995.

24. Heron J. Catharsis in human development. Human Potential Research, Surrey: University of Surrey, 1977.

25. Adlam, Plumridge, Organisational effectiveness.

26. Vaughan A. Incredible coincidence: the baffling world of synchronicity. New York: J B Lippincott, 1979.

27. Redfield J. The Celestine philosophy. London: Bantam Books, 1994.

28. Covey, Seven habits: 267.

29. Jaworski J. Synchronicity: the inner path of leadership. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1996.

30. Macquarrie J. Existentialism. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973.

31. Maslow A. The farther reaches of human nature. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

32. Rogers C. Freedom to learn. Columbus, OH: C E Merrill, 1969.

33. Harrison R. Organisation culture and quality of service: a strategy for releasing love in the workplace. London: Association of Management and Education Development, 1987.

34. Clutterbuck D. A personal development plan for every citizen. People Management 12 September 1996: 23.

35. Van Dyne L, Graham J, Dienesch R. Organisational citizenship behaviour: construct redefinition, measurement and validation. Academy of Management Journal 1994: 37(4): 765–802.

36. Caulkin S. The New Avengers. Management Today November 1995: 48–52.

37. Redman W. Portfolios for development: a guide for trainers and managers. London: Kogan Page, 1994.

38. Critten P. Developing your professional portfolio. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1995.

39. Redman, Portfolios.

40. Pedler, Boydell, Manager’s guide.

41. Critten, Developing your professional portfolio.

42. Critten, Developing your professional portfolio.

43. Heron, Catharsis.

44. Clutterbuck D. Everyone needs a mentor: fostering talent at work. London: IPD, 1991.

45. Harri-Augstein S, Thomas L. Self-organised learning for personal and organisation growth. Training and Development UK 1992; 10(6): 19–21.

46. Revans R. The origins and growth of action learning. Bromley: Chartwell Bratth, 1982.

47. Wynstein K. Action learning: a journey in discovery and development. London: HarperCollins, 1995.

48. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English. 9th edition, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

49. Clyne S. Continuing professional development: perspectives on CPD in practice. London: Kogan Page, 1995.

50. Clyne, Continuing professional development.

51. Winter R, Maisch M. Professional competence and higher education: the ASSET programme. London: Falmer Press, 1996.

52. Schon D. The reflective practitioner. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

53. Schon D. Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987.

54. Schon, Educating the reflective practitioner.

55. Schon, Educating the reflective practitioner.

56. Schon, Educating the reflective practitioner.

57. Winter, Maisch, Professional competence.

58. Hartog M. Shortfalls in professional education for the personnel and development practitioner. Paper given at HEC Conference on Capability and Professionalism, London, January 1996.

59. Fish D. Reflection on theory and practice — a holistic approach to professional education. BDA Conference Papers 1991.

60. Titchen AC. Design and implementation of a problem-based continuing education programme. a guide for clinical physiotherapists. Physiotherapy 1987; 73(7): 318–323.

61. Schon, Educating the reflective practitioner.

62. Schon D. Beyond the stable state. London: Temple Smith, 1971.

63. Winter, Maisch, Professional competence.

64. Mansfield B, Mitchell L. Towards a competent workforce. Aldershot: Gower, 1996.

65. Fowler B. Management Charter Initiative personal competence model: use and implementation. Sheffield: Employment Department, 1994.

66. Handy C. The age of unreason. London: Hutchinson, 1989.

67. Taylor FW. The principles of scientific management. New York: Harper & Row, 1911.

68. Redman, Portfolios.

69. Redman, Portfolios.

70. Critten P. Investing in People: towards corporate capability. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993.

71. Inkson K. Managerial careers: facing the new reality. Professional Manager 1993; July: 14–15.