Designing a Compensation System

An employee’s paycheck is certainly important for its purchasing power. In most societies, however, a person’s earnings also serve as an indicator of power and prestige and are tied to feelings of self-worth. In other words, compensation affects a person economically, sociologically, and psychologically.10 For this reason, mishandling compensation issues is likely to have a strong negative impact on employees and, ultimately, on the firm’s performance.11

The wide variety of pay policies and procedures presents managers with a two-pronged challenge: to design a compensation system that (1) enables the firm to achieve its strategic objectives and (2) is molded to the firm’s unique characteristics and environment.12 We discuss the criteria for developing a compensation plan in the sections that follow and summarize these options in Figure 10.2. Although we present each of these as an either/or choice for the sake of simplicity, most firms institute policies that fall somewhere between the two poles.

Internal Versus External Equity Will the compensation plan be perceived as fair within the company, or will it be perceived as fair relative to what other employers are paying for the same type of labor?

Fixed Versus Variable Pay Will compensation be paid monthly on a fixed basis—through base salaries—or will it fluctuate depending on such preestablished criteria as performance and company profits?

Performance Versus Membership Will compensation emphasize performance and tie pay to individual or group contributions, or will it emphasize membership in the organization—logging in a prescribed number of hours each week and progressing up the organizational ladder?

Job Versus Individual Pay Will compensation be based on how the company values a particular job, or will it be based on how much skill and knowledge an employee brings to that job?

Egalitarianism Versus Elitism Will the compensation plan place most employees under the same compensation system (egalitarianism), or will it establish different plans by organizational level and/or employee group (elitism)?

Below-Market Versus Above-Market Compensation Will employees be compensated at below-market levels, at market levels, or at above-market levels?

Monetary Versus Nonmonetary Awards Will the compensation plan emphasize motivating employees through monetary rewards such as pay and stock options, or will it stress nonmonetary rewards such as interesting work and job security?

Open Versus Secret Pay Will employees have access to information about other workers’ compensation levels and how compensation decisions are made (open pay), or will this knowledge be withheld from employees (secret pay)?

Centralization Versus Decentralization of Pay Decisions Will compensation decisions be made in a tightly controlled central location, or will they be delegated to managers of the firm’s units?

FIGURE 10.2 The Nine Criteria for Developing a Compensation Plan

Internal Versus External Equity

Fair pay is pay that employees generally view as equitable. There are two forms of pay equity. Internal equity refers to the perceived fairness of the pay structure within a firm. External equity refers to the perceived fairness of pay relative to what other employers are paying for the same type of labor.

In considering internal versus external equity, managers can use two basic models: the distributive justice model and the labor market model.

The Distributive Justice Model

The distributive justice model of pay equity holds that employees exchange their contributions or input to the firm (skills, effort, time, and so forth) for a set of outcomes. Pay is one of the most important of these outcomes, but nonmonetary rewards, such as a company car, may also be significant. This social–psychological perspective suggests that employees are constantly (1) comparing what they bring to the firm to what they receive in return and (2) comparing this input/outcome ratio with that of other employees within the firm. Employees will think they are fairly paid when the ratio of their inputs and outputs is equivalent to that of other employees whose job demands are similar to their own.

The Labor Market Model

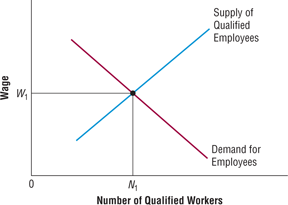

According to the labor market model of pay equity, the wage rate for any given occupation is set at the point where the supply of labor equals the demand for labor in the marketplace (W 1 in Figure 10.3). In general, the less employers are willing to pay (low demand for labor) and the lower the pay workers are willing to accept for a given job (high supply of labor), the lower the wage rate for that job.13

FIGURE 10.3

The Labor Market Model

The actual situation is a great deal more complicated than this basic model suggests. People base their decisions about what jobs they are willing to hold on many more factors than just pay. Moreover, the pay that an employer offers is based on many factors besides the number of available people with the skills and abilities to do the job. A complete exploration of this topic is beyond the scope of this book. However, the basic point of the labor market model is that external equity is achieved when the firm pays its employees the “going rate” for the type of work they do.14 For a growing number of managerial, professional, and technical occupations, the “going rate” is determined not only by local and domestic factors, but also by global forces.15

In general, salary dispersion increases for higher occupational levels and for broader geographic areas. For instance, according to [no longer online] Salary.com, in 2013 the salary range for a chief financial officer at a U.S. firm was between $179,820 (lowest 10%) and $466,341 (highest 10%). In contrast, the salary range for an administrative assistant was from $33,217 (lowest 10%) to $56,607 (highest 10%).16

Balancing Equity

Ideally, a firm should try to establish both internal and external pay equity, but these objectives are often at odds. For instance, universities sometimes pay new assistant professors more than senior faculty who have been with the institution for a decade or more,17 and firms sometimes pay recent engineering graduates more than engineers who have been on board for many years.18

Many firms also have to determine which employee groups’ pay will be adjusted upward to meet (or perhaps exceed) market rates. This decision is generally based on each group’s relative importance to the firm. For example, marketing employees tend to be paid more in firms that are trying to expand their market share and less in older firms that have a well-established product with high brand recognition.

Once a decision has been made as to which groups will be adjusted upward, one difficult challenge remains: What to do with “superstars.” In some cases, these individuals command a much higher salary than the average of those holding the same title. For instance, U.S. universities are expanding their business faculty. This has driven up business faculty salaries, which averaged more than $155,150 a year in 2014, making it one of the highest-paid occupational groups that the government tracks.19 Yet even at an elite school, a top business faculty member can earn more than double the average earnings of his or her peers of the same rank in the same department. Some compensation professionals refer to this type of pay as having individual equity , because it is based on the value to the institution of specific people rather than of the job group, position title, or class to which they belong. Individual equity decisions are becoming more important in professions where some key people can make a big difference and where there is high performance variance. These typically include such occupations as top executives, sales, scientists and engineers, software development, and the like. Individual equity decisions may be controversial because these generally require subjective judgments as to how much each employee is worth to the firm; if not justified carefully, real or perceived favoritism would tarnish the whole process.

In general, emphasizing external equity is more appropriate for newer, smaller firms in a rapidly changing market. These firms often have a high need for innovation to remain competitive and are dependent on key individuals to achieve their business objectives.20

When faced with choosing between internal and external equity, an increasing number of firms have opted to offer large “sign-on bonuses” to new employees in order to entice good candidates without disrupting the existing salary schedules. A survey of 348 large and small firms that use sign-on bonuses indicated 80 percent of them use sign-on bonuses for professional staff and executives; 70 percent for midlevel managers and information technology personnel; 60 percent for sales, lower-level managers, and technical staff; and 20 percent for clerical workers. In a sense, the new employee receives a big pay raise “up front”—in many cases 25 percent or more of annual salary—and the company avoids the need to reduce posted salary differentials between junior and senior employees.21

In recent years, another interesting twist to the balancing equity dilemma is the practice in which companies facing uncertain financial futures shower “retention bonuses” on key employees . The objective is to retain needed expertise without having to raise the entire salary schedule—which might hasten the firm’s demise. For instance, a few years back Kmart spent upward of $92 million in retention bonuses for 9,700 key employees as it filed for bankruptcy protection. Other well-publicized cases of companies that did the same include Enron, Polaroid, Bradlees Inc., and Aerovox, Inc.22 Some financial institutions bailed out by the federal government during 2008–2011 paid retention bonuses to key employees, a move that some people thought was akin to rewarding those who were responsible for the crisis in the first place. A 2013 survey indicates that 59.1 percent of companies are very concerned with losing good employees and the majority of these utilize incentives to reduce turnover.23

Firms can also provide “adds ons” or “caps,” which are renegotiable on an individual basis. Going back to the example of business faculty, one way many universities handle the individual-equity challenge is to base all professors’ salaries on a nine-month academic year schedule (usually mid-August to mid-May). Those who are exceptional contributors receive a summer stipend that often adds up to a third of the nine-month salary. They may also receive other perks, such as large travel budgets, research support, secretarial assistance, and the like. These “chairs” or “fellowships,” as they are usually called, are often renegotiated at certain fixed intervals.

Lastly, a growing number of firms have developed explicit “counteroffer” policies . This means that the organization will match or closely match the compensation offer an employee receives from a competitor, but only if certain criteria are met (for example, the offer comes from a leading-edge company). According to a recent survey, 55 percent of firms make counteroffers, but only for employees who are in key positions and those who are outstanding performers.24

Fixed Versus Variable Pay

Firms can choose to pay a high proportion of total compensation in the form of base pay (for example, a predictable monthly paycheck) or in the form of variable pay that fluctuates according to some preestablished criterion. On average, approximately 75 percent of firms offer some form of variable pay and this proportion continues to increase over the years.25

There is a great deal of variation in the way firms answer the fixed versus variable pay question. On average, 10 percent of an employee’s pay in the United States is variable. This compares to 20 percent in Japan. However, the range is huge in both countries—from 0 percent up to 70 percent. For select employee groups (such as sales), variable pay can be as high as 100 percent.26 In general, the proportion of variable pay increases as an employee’s base pay increases, indicating that those in higher-level positions earn more but their overall compensation is more subject to risk. According to most recent estimates, for employees earning more than $950,000 a year in base pay, variable compensation is close to 90 percent of base pay. For those earning less than $35,000 a year in base pay, this percentage drops to less than 5 percent.27

Fixed pay is the rule in the majority of U.S. organizations largely because it reduces the risk to employees and it is easier to administer. However, variable pay can be used advantageously in smaller companies, firms with a product that is not well established, companies with a young professional workforce that is willing to delay immediate gratification in hopes of greater future returns, firms supported by venture capital, organizations going through a prolonged period of cash shortages, and companies that would otherwise have to institute layoffs because their revenues are volatile. The Manager’s Notebook, “Compensation Entitlements Are Going Out the Window ,” gives examples of the many risks employees now bear with regard to their pay.

MANAGER’S NOTEBOOK Compensation Entitlements Are Going Out the Window

Emerging Trends

Not too long ago employers divided pay into fixed (salaries), variable (incentives), and benefits components. Except for incentive pay, which for most employees was a small percentage of their total compensation, workers could count on a promised salary and future benefits as a condition for employment. But this is changing rapidly, as the following examples demonstrate.

Shift to Variable Pay Plans Continues

In a recent survey, Perrin Watson Consulting found that 82 percent of companies have a variable pay program for nonexecutive employees and 49 percent have a variable pay plan for all employees. Furthermore, 46 percent are increasing the goals that employees are required to meet in order to earn an award.

Race to the Bottom: Mexico Lowers Wages to Snare International Auto Production

Wage concessions were apparently key to persuading Ford Motor Co. to direct many of the 4,500 new jobs involved in building its Fiestas to the Ford plant in Cuautitlan, which is on the outskirts of Mexico City. Wages for new hires were cut to about half of the standard wage of $4.50 per hour. With labor costs like these, Mexico is staying competitive with China, where an average worker at a foreign-owned factory or joint venture can make $2 to $6 per hour. In the United States, General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford have reduced salaries of nonunion staff by as much as 28 percent in an effort to boost profits.

Making Wage Concessions at Airlines

Frontier Airlines, which employs 6,000 aviation professionals, made cuts of up to 20 percent in wages and benefits for the executive management team during 2009–2011 and has asked all of its employees to make wage and benefit concessions in the upcoming years. Similarly, United Airlines has cut pilots’ pay by 12 percent and flight attendants’ pay by 9.5 percent, in addition to reducing benefits. United has joined the ranks of American Airlines, Continental (which later merged with United), Delta, and US Airways (which later merged with American), which have all made salary and benefit cuts. The wave of mergers in the industry has compounded this problem for employees as there are fewer and fewer options in alternative airlines to find another job.

Pensions Going Up in Smoke

It used to be that pensions were a sacred cow, particularly in the public sector where employees often accepted lower salaries in exchange for generous pension plans. But employees are increasingly faced with big surprises in what they thought was a sure deal. The city of Detroit is just the latest example of a municipality using bankruptcy to negotiate reduced pension payments to employees. As another recent example, The City of Stockton, California, owes $900 million to CalPERS, the state-run pension plan, and is reneging on its pension promises to employees.

Medical Doctors Being Squeezed

Not long ago medical doctors were at the top of all professions in terms of earned income. However, their enviable position has eroded over the years due to shrinking payments by private insurance companies, lower government reimbursement for patients covered under Medicaid and Medicare, and higher malpractice insurance. As a result, an increasing number of doctors are filing for bankruptcy. A recent example is that of oncologist Dr. Dennis Morgan from Enfield, Connecticut: “Revenues began to fall when reimbursements for treatment and drugs to oncologists started shrinking. I made cutbacks but began having trouble meeting expenses and my debt grew. Critical chemotherapy drug and medical supply providers eventually cut me off.”

Documenting Pay Cuts Around the World

A quick search through Google at the time of this writing (2015) shows numerous Web sites documenting hundreds of organizations in the United States and abroad that have implemented pay cuts.

Apple Inc. provides an excellent example of a firm that used variable pay to its own and its employees’ advantage. In its early years, employees were willing to work for low salaries for several years in exchange for company stock; many who persevered became millionaires after the value of Apple’s stock went sky high in the mid-1980s. Software maker Symantec saw its stock increase 150 percent during 2003–2005, and a high percentage of employees received huge gains during that period because they were all eligible for stock options.28

As we will discuss in Chapter 11, t ax regulations in effect since fiscal year 2006 are putting a damper on the use of stock options. But this has not stopped firms from experimenting with other types of variable pay. For example, Nordstrom recently gave each employee who worked at least 1,000 hours a year a profit-sharing bonus that was triple what it had been in prior years.29 Pella, a maker of windows and doors with more than 8,000 employees, has an official policy of giving employees 25 percent of its pretax profits in addition to their normal salaries. Network Appliance, a hardware and software provider, gives employees $5,000 to $10,000 for each patent they file.

Not all variable-pay plans work out well for employees, however. Employees at Enron and Global Crossing saw their stock holdings drop from $90 per share to about 50 cents per share within months, partly due to company mismanagement and partly due to corruption at the top.30 In less than a year, in response to the housing crisis, employees saw their stock options drop dramatically in value during 2008–2009 at now-bankrupt Lehman Brothers (95%), Merrill Lynch (69%), and AIG (90%). In fact, from 2009 to 2011, approximately 10 percent of salaried employees across a wide variety of firms were unpleasantly surprised to find that the wealth they thought they accumulated during years of hard work had evaporated, and in some cases had left them with a big tax bill as well.31 On the other hand, most employees have seen significant increases in their shareholdings’ value during 2012–2014, showing that the risk is real but so are the potential high returns. What is clear, however, is that fixed pay as a percentage of total compensation continues to decline, and firms are asking employees to share more risks with them.32 Those firms that treat employees fairly and that clearly communicate to them the downside and upside of the compensation risk they face are more likely to prevent a deterioration of morale in spite of the added stress. For example, Emmis Communications, a chain of magazines and radio and TV stations, recently cut pay 10 percent when faced with a profit crunch. Surprisingly, few people left, and employees accepted the bad news as well as could be expected.33

Performance Versus Membership

A special case of fixed versus variable compensation requires a choice between performance and membership.34 A company emphasizes performance when a substantial portion of its employees’ pay is tied to individual or group contributions and the amount received can vary significantly from one person or group to another. The most extreme forms of performance-contingent compensation are traditional piece-rate plans (pay based on units produced) and sales commissions. Other performance-contingent plans use awards for cost-saving suggestions, bonuses for perfect attendance, or merit pay based on supervisory appraisals. All these options are provided on top of an individual’s base pay (see Chapter 11).

Firms that emphasize membership-contingent compensation provide the same or a similar wage to every employee in a given job, as long as the employee achieves at least satisfactory performance. Employees receive a paycheck for logging in a prescribed number of hours of work per week (normally 40). Typically, salary progression occurs by moving up in the organization, not by doing the present job better.

The relative emphasis placed on performance and membership depends largely on the organization’s culture and the beliefs of top managers or the company’s founder. Most companies that emphasize performance tend to be characterized by fewer management levels, rapid growth, internal competition among people and groups, readily available performance indicators (see Chapter 7), and strong competitive pressures.35 Regardless of company size, there seems to be a trend not only in the United States, but also in many other countries, away from membership-contingent compensation.36 Global competition is likely to accelerate this trend as we progress through the second decade of the twenty-first century.37 This raises another question: should a multinational measure performance at the plant level, at the national level, or across the entire globe? IBM has decided to measure profitability for the entire corporation with the objective of focusing employees’ attention, no matter where they work, on worldwide performance. Other companies, however, believe that the “line of sight” between employee behavior and performance is more direct if rewards are based on the profitability of local units.

Most organizations struggle with the choice of criteria to reward performance. For example, some companies such as Intel consider community service as a performance criterion . As another example, teachers in many jurisdictions are being held accountable for how much students learn as well as for enhancing students’ welfare. One challenge in the choice of performance criteria is determining how much control the employee actually has over the criteria in question. The Manager’s Notebook, “Paying Teachers for Student Welfare, ” discusses how well-meaning attempts to measure important performance aspects may lead to charges of unfairness.

MANAGER’S NOTEBOOK Paying Teachers for Students’ Welfare

Ethics/Social Responsibility

There has been a major push in recent years to reward teachers for promoting the welfare of students. In one midwestern state, for instance, teachers are given bonuses for ensuring that students meet state-defined targets for physical education "such as consistently demonstrating correct skipping techniques with a smooth and effortless rhythm and strike consistently a ball with a paddle to a target area with accuracy and good technique." In many jurisdictions around the country, pay-for-performance in K–12 now translates into rewards for teachers pegged to improvements in test scores. Common complaints with these well-intentioned programs are that teachers are induced to teach students how to do well on the tests (perhaps while sacrificing critical thinking and general learning) and that the system is unfair because teachers are made accountable for variables they can’t control (such as the socioeconomic status of students, school funding, and family life).