Equal Employment Opportunity Laws

The laws that affect HR issues can be divided into two broad categories: (1) equal employment opportunity laws and (2) everything else. We will spend the bulk of this chapter on the EEO laws because these are the ones that most affect a manager’s day-to-day behavior. In addition, the EEO laws cut across almost every other issue that we discuss in this text. The other laws tend to be more specifically focused, and we discuss them in the context in which they apply. For instance, we discuss the laws governing union activities in Chapter 15 and the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) in Chapter 16.

The major EEO laws are the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 has been amended through the years, most recently in 1991. The theme that ties these laws together is simple: Employment decisions should not be based on characteristics such as race, sex, age, or disability.

The Equal Pay Act of 1963

The first of the civil rights laws was the Equal Pay Act , which became law in 1963. It requires that men and women who do the same job in the same organization should receive the same pay. “Same pay” means that no difference is acceptable.

Determining whether two employees are doing the same job can be difficult. The law specifies that jobs are the same if they are equal in terms of skill, effort, responsibility, and working conditions. Thus, it is permissible to pay one employee more than another if the first employee has significant extra job duties, such as supervisory responsibility. Pay can also be different for different work shifts. The law also specifies that equal pay is required only for jobs held in the same geographic region. This allows an organization to make allowances for the local cost of living and the fact that it might be harder to find qualified employees in some areas.

The law contains several explicit exceptions. First, it does not prohibit the use of a merit pay plan. That is, an employer can pay a man more if he is doing a better job than his female coworker. In addition, companies are permitted to pay for differences in quantity and quality of production. Seniority plans also are exempted; a company that ties pay rates to seniority can pay a man more if he has been with the company longer than a female employee. Finally, the law indicates that any factor other than sex may be used to justify different pay rates.11

When the Equal Pay Act was passed, the average female employee earned only about 59 cents for each dollar earned by the average male worker. While this gap has narrowed in the intervening years, to about 83 cents in 2010,12 this average differential remains troubling, and in some jobs it is much higher. For instance, 30-year-old male sales representatives earned an average of $60,000 in 2001, whereas their female counterparts in sales, doing the same amount and same kind of work, earned only an average of $36,000 at the same age.13 Some states, such as Washington and Illinois, have responded to this issue by requiring that civil service employers pay equally for work of comparable worth.14 Understanding equal pay and comparable worth requires more knowledge of compensation decisions, so we will return to these issues in Chapter 10.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Although not the oldest of the civil rights laws, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is universally seen as the most important passed to date. This law was enacted in the midst of the seething civil rights conflicts of the 1960s, one year after the civil rights march on Washington at which Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Before passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, open and explicit discrimination based on race, particularly against African Americans, was widespread. Jim Crow laws legalized racial segregation in many southern states. The act itself had several sections, or titles, all of which aim to prohibit discrimination in various parts of society. For instance, Title IX applies to educational institutions. Title VII applies to employers that have 15 or more employees, as well as to employment agencies and labor unions.

General Provisions

Title VII prohibits employers from basing employment decisions on a person’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. The heart of the law, Section 703(a), is reprinted in Figure 3.2. Note that employment decisions include “compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment.”

Title VII clearly covers persons of any race, any color, any religion, both sexes, and any national origin. However, as court cases and regulations have grown up around this law, so has the legal theory of a protected class . This theory states that groups of people who suffered discrimination in the past require, and should be given, special protection by the judicial system. Under Title VII, the protected classes are African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and women. Although it is not impossible for a nonprotected-class plaintiff to win a Title VII case, it is highly unusual.

Section 703. (a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer—

to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or applicants for employment in any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

FIGURE 3.2

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Discrimination Defined

Despite the negative connotation the word has acquired, discrimination simply means making distinctions—in the HR context, distinctions among people. Therefore, even the most progressive companies are constantly discriminating when they decide who should be promoted, who should receive a merit raise, and who should be laid off. What Title VII prohibits is discriminating among people based on their race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Specifically, Title VII makes two types of discrimination illegal. The first type of discrimination, disparate treatment , occurs when an employer treats an employee differently because of his or her protected-class status. Disparate treatment is the kind of treatment that you probably first think of when considering discrimination. For instance, Robert Frazier, a bricklayer’s assistant and an African American, was fired after quarreling with a white bricklayer. However, Frazier’s employer did not discipline the white bricklayer at all, even though he had injured Frazier by throwing a broken brick at him. A federal court judge ruled that Frazier had been treated more harshly because of his race and thus suffered from disparate treatment discrimination.15

The second type of discrimination, adverse impact (also called disparate impact), occurs when the same standard is applied to all applicants or employees, but that standard affects a protected class more negatively (adversely). For example, most police departments around the United States have dropped the requirement that officers be of a minimum height because the equal application of that standard has an adverse impact on women, Latinos, and Asian Americans (that is, any given height standard will rule out more women than men, and more Latinos and Asian Americans than African Americans and nonminority individuals).

The adverse impact definition of discrimination was confirmed in a very important 1971 Supreme Court case that we have already discussed, Griggs v. Duke Power.16 Griggs was an African American employee of the Duke Power Company in North Carolina. He and other African American employees were refused promotions because Duke Power, on the day that Title VII took effect, had implemented promotion standards that included a high school diploma and passing scores on two tests, one of general intellectual ability and one of mechanical ability. The Supreme Court ruled that such standards, even though applied equally to all employees, were discriminatory because (1) they had an adverse impact on a protected class (in this case, African Americans) and (2) Duke Power was unable to show that the standards were related to subsequent job performance.

Griggs v. Duke Power has some important implications. Under the Griggs ruling, courts may find that a company is acting in a discriminatory manner even though it works hard to ensure that its HR decision processes are applied equally to all employees. If the outcome is such that a protected class suffers from adverse impact, then the organization may be required to demonstrate that the standards used in the decision process were related to the job. In October 1993, Domino’s Pizza lost a case in which it attempted to defend a “no-beard policy.” The appellate court ruled that the policy had an adverse effect on African Americans because almost half of male African Americans suffer from a genetic condition that makes shaving very painful or impossible. Almost no white men suffer from this malady. Therefore, African Americans are more adversely affected by this requirement than whites are.17 Domino’s could have won this case if it had shown that not having a beard was necessary for good job performance. It could not, so the court ruled the no-beard policy a violation of Title VII.

In an earlier (1975) case, Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, the Supreme Court established procedures to help employers determine when it is appropriate to use employment tests as a basis for hiring or promoting employees. The Court ruled that employers can use an employment test only when they can demonstrate that the test is a valid predictor of job performance. Thus, Albemarle places the burden of proof on the employer to prove that a contested test (for example, a test that has an adverse impact on a protected class) or other selection tool is a valid predictor of job success.18

Defense of Discrimination Charges

When a discrimination case makes it to court, it is the responsibility of the plaintiff (the person bringing the complaint) to show reasonable evidence that discrimination has occurred. The legal term for this type of evidence is prima facie, which means “on its face.” In a disparate treatment lawsuit, to establish a prima facie case the plaintiff only needs to show that the organization did not hire her (or him), that the plaintiff appeared to be qualified for the job, and that the company continued to try to hire someone else for the position after rejecting the plaintiff. This set of requirements, which originated from a court case brought against the McDonnell-Douglas Corporation, is often called the McDonnell-Douglas test.19 In an adverse impact lawsuit, the plaintiff only needs to show that a restricted policy is in effect—that is, that a disproportionate number of protected-class individuals were affected by the employment decisions.

One important EEOC provision for establishing a prima facie case that an HR practice is discriminatory and has an adverse impact is the four-fifths rule . The four-fifths rule comes from the EEOC’s Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures, an important document that informs employers how to establish selection procedures that are valid and, therefore, legal.20

The four-fifths rule compares the hiring rates of protected classes to those of majority groups (such as white men) in the organization. It assumes that an HR practice has an adverse impact if the hiring rate of a protected class is less than four-fifths the hiring rate of a majority group. For example, assume that an accounting firm hires 50 percent of all its white male job applicants for entry-level accounting positions. Also assume that only 25 percent of all African American male job applicants are hired for the same job. Applying the four-fifths rule, prima facie evidence indicates that the accounting firm has discriminatory hiring practices because 50 percent × 4/5 = 40 percent, and 40 percent exceeds the 25 percent hiring rate for African American men.

Once the plaintiff has established a prima facie case, the burden of proof switches to the organization. In other words, the employer is then placed in a position of proving that illegal discrimination did not occur. This can be very tough to prove. Suppose that a sales manager interviews two applicants for a sales position, a man and a woman. Their qualifications look very much the same on paper. However, in the interview the man seems to be more motivated. He is hired, and the rejected female applicant files a disparate treatment discrimination suit. She can, almost automatically, establish a prima facie case (she was qualified, she was not hired, and the company did hire someone else). Now the sales manager has to prove that the decision was based on a judgment about the applicant’s motivation, not on the applicant’s sex.

Although these cases can be difficult, employers do win their share of them. There are four basic defenses that an employer can use:

-

▪ Job relatedness The employer has to show that the decision was made for job-related reasons. This is much easier to do if the employer has written documentation to support and explain the decision. In our example, the manager will be asked to give specific job-related reasons for the decision to hire the man for the sales job. As we noted in Chapter 2, job descriptions are particularly useful for documenting the job-related reasons for any particular HR decision.

-

▪ Bona fide occupational qualification A bona fide occupational qualification (BFOQ) is a characteristic that must be present in all employees for a particular job. For instance, a film director is permitted to consider only females for parts that call for an actress. An airline company must apply a compulsory age ceiling for pilots, according to Federal Aviation Agency rules, so that age is a BFOQ for airline pilots.

-

▪ Seniority Employment decisions that are made in the context of a formal seniority system are permitted, even if they discriminate against certain protected-class individuals. However, this defense requires the seniority system to be well established and applied universally, not just in some circumstances.

-

▪ Business necessity The employer can use the business necessity defense when the employment practice is necessary for the safe and efficient operation of the organization and there is an overriding business purpose for the discriminatory practice. For example, an employee drug test may adversely impact a disadvantaged minority group, but the need for safety (to protect other employees and customers) may justify the drug-testing procedure.

Of these four defenses, the job-relatedness defense is the most common because of the strict limitations courts have placed on the BFOQ, seniority, and business-necessity defenses.

When an employer requires employees to speak only English at all times on the job, this speak-English-only rule may violate EEOC law, unless the employer can show that the rule is necessary for conducting business.21 Similarly, an employer may not deny an individual an employment opportunity, such as a job or promotion, if the individual speaks with an accent, unless the employer can show that speaking with an accent has a detrimental effect on job performance.

Title VII and Pregnancy

In 1978, Congress amended Title VII to state explicitly that women are protected from discrimination based either on their ability to become pregnant or on their actual pregnancy. The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 requires employers to treat an employee who is pregnant in the same way as any other employee who has a medical condition.22 For instance, an employer cannot deny sick leave for pregnancy-related illnesses such as morning sickness if the employer allows sick leave for other medical conditions such as other illnesses that cause nausea. The law also states that a company cannot design an employee health benefit plan that provides no coverage for pregnancy. These are strict requirements, as evidenced by the following cases.

In one case that applied the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, a woman who worked at the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) claimed she was subjected to pregnancy discrimination when she was not reappointed after she had served a one-year appointment. The USPS cited her absences from work and that she was considered a high-risk pregnancy and should be doing only light-duty work. However, the EEOC found the complainant was treated less favorably than comparative employees based on her pregnancy. The basis of the EEOC’s ruling was that the law requires the employer to treat pregnant employees just as it treats other employees with temporary impairments.23

A female police officer in Pinellas Park, Florida, claimed she experienced pregnancy discrimination when she was demoted to dispatcher after becoming pregnant and requesting light duty. She showed evidence that her male supervisor informed her that he was forced to hire women, and he specifically gave women the least desirable shifts and days off to punish them if they became pregnant. The city settled in favor of the complainant and reinstated her as a police officer.24

Sexual Harassment

The Title VII prohibition of sex-based discrimination has also been interpreted to prohibit sexual harassment. In contrast to protection for pregnancy, sexual harassment protection was not an amendment to the law but rather a 1980 EEOC interpretation of the law.25 The EEOC’s definition of sexual harassment is given in Figure 3.3. Also shown in the figure is the definition of general harassment that the EEOC issued in 1993. The majority of harassment cases filed to date have dealt with sexual harassment, but this may change in the future.26 Courts appear to be extending sexual harassment definitions to other protected classes, such as race, age, and disability.

There are two broad categories of sexual harassment. The first, quid pro quo sexual harassment , covers the first two parts of the EEOC’s definitions. It occurs when sexual activity is demanded in return for getting or keeping a job or job-related benefit.27 For instance, a buyer for the University of Massachusetts Medical Center was awarded $1 million in 1994 after she testified that her supervisor had forced her to engage in sex once or twice a week over a 20-month period as a condition of keeping her job.28

The second category, hostile work environment sexual harassment , occurs when the behavior of coworkers, supervisors, customers, or anyone else in the work setting is sexual in nature and the employee perceives the behavior as offensive and undesirable.29

1980 Definition of Sexual Harassment

Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitute sexual harassment when:

submission to such conduct is made either explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment;

submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as a basis for employment decisions affecting such individual; or

such conduct has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.

1993 Definition of Harassment

Unlawful harassment is verbal or physical conduct that denigrates or shows hostility or aversion toward an individual because of his or her race, color, religion, gender, national origin, age or disability, or that of his/her relatives, friends, or associates, and that:

has the purpose or effect of creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment;

has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual’s work performance; or

otherwise adversely affects an individual’s employment opportunities.

FIGURE 3.3

EEOC Definitions of Harassment

Consider this example from a Supreme Court case decided in 1993.30 Teresa Harris was a manager at Forklift Systems, Inc., an equipment rental firm in Nashville, Tennessee. Her boss was Charles Hardy, the company president. Throughout the two and one-half years that Harris worked at Forklift, Hardy made such comments to her as “You’re a woman, what do you know?” and “We need a man as the rental manager.” He suggested in front of other employees that the two of them “go to the Holiday Inn to negotiate her raise.” When Harris asked Hardy to stop, he expressed surprise at her annoyance but did not apologize. Less than one month later, after Harris had negotiated a deal with a customer, Hardy asked her in front of other employees, “What did you do, promise the guy . . . some [sex] Saturday night?” Harris quit her job at the end of that month.

The issue the Court had to decide was whether Hardy violated the sexual harassment regulations based on Title VII. Lower courts had held that Hardy’s behavior was certainly objectionable, but that Harris had not suffered serious psychological harm and that Hardy had not created a hostile work environment. The Supreme Court disagreed, holding that the behavior only needed to be such that a “reasonable person” would find it to create a hostile or abusive work environment. Figure 3.4 lists the tests that the Supreme Court said should be considered by judges and juries in deciding whether certain conduct creates a “hostile work environment” and is thus prohibited by Title VII.

The Supreme Court listed these questions to help judges and juries decide whether verbal and other nonphysical behavior of a sexual nature create a hostile work environment:

How frequent is the discriminatory conduct?

How severe is the discriminatory conduct?

Is the conduct physically threatening or humiliating?

Does the conduct interfere with the employee’s work performance?

FIGURE 3.4

Do You Have a Hostile Work Environment?

Some cases of sexual harassment have involved groups of employees who have lodged hostile work environment claims. In 1998, Mitsubishi Motor Manufacturing of America paid out $34 million to settle a sexual harassment case brought by the EEOC on behalf of more than 300 female employees. Among their complaints were their being groped, gestured to, urged to reveal their sexual preferences, and exposed to sexually explicit pictures.31 In 1999, Ford Motor Company achieved a settlement with women in two Chicago area factories in regard to their sexual harassment complaints. The female employees claimed a long-term pattern of groping, name-calling, and partying with strippers and prostitutes. The carmaker agreed to set aside $7.5 million to compensate victims of harassment and $10 million more to provide diversity training to managers and male workers.32 Mitsubishi changed its image from a leader in corporate forgiveness of sexual harassment in 1998 to a model corporate citizen four years later in 2002. Mitsubishi made improvements that included a zero-tolerance policy for sexual harassment and providing training for all employees about the illegality of harassment and how to investigate complaints when they arise.33

Sexual harassment cases are not only expensive, but they also can be highly disruptive to business and political organizations. Consider the disruption to the executive branch of the U.S. government when Paula Jones sued President Clinton for sexual harassment. She alleged that the president made an unwanted sexual advance toward her in 1991 while he was the governor of Arkansas and she was a state employee. In 1999, President Clinton paid $850,000 to settle the suit.34

More recently, in 2007 a jury found that Madison Square Garden and New York Knicks coach and president for basketball operations Isiah Thomas sexually harassed and discriminated against Anucha Browne Sanders, a former senior vice president of the Knicks, and ordered that the company pay her $11.6 million in punitive damages.35

Anucha Brown Sanders, former senior vice president of the Knicks, settled her sexual harassment lawsuit against the organization and former coach Isiah Thomas for $11.6 million.

Source:Julie Stapen/Newscom.

Although most sexual harassment cases involve women as victims, the number of cases in which men are the victims is increasing.36 In 1995, a federal judge awarded a man $237,257 for being sexually harassed by a female supervisor at a Domino’s Pizza restaurant. The female supervisor made unwelcome sexual advances to the male subordinate, creating a hostile work environment. When the man threatened to report the supervisor’s inappropriate conduct to top management, he was fired.37

Courts also consider same-sex harassment improper work-related behavior. Joseph Oncale, an oil-rig worker who alleged that fellow male workers physically and verbally abused him with sexual taunts and threats, was allowed to bring a sexual harassment lawsuit against his employer. Despite arguments to the contrary, a court reviewing the Oncale case ruled in 1998 that same-sex harassment, not just harassment occurring between the sexes, can be the basis for a sexual harassment lawsuit.38

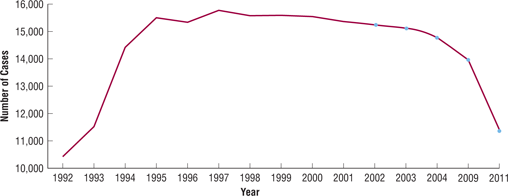

As Figure 3.5 indicates, sexual harassment is a major EEO issue for employers. An ABC News/Washington Post poll found that 25 percent of women and 10 percent of men reported that they had been sexually harassed in the workplace.39 According to the EEOC, plaintiffs filed 11,364 cases of sexual harassment with federal and state agencies in 2011 (Figure 3.5). Men filed approximately 16 percent of those cases.

FIGURE 3.5

Number of Sexual Harassment Charges in the United States from 1992 to 2011

Source:The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2012).

www.eeoc.gov/

The Manager’s Notebook titled “Reducing Potential Liability for Sexual Harassment” spells out some ways to prevent or correct instances of sexual harassment.

MANAGER’S NOTEBOOK Reducing Potential Liability for Sexual Harassment

![]() Customer-Driven HR

Customer-Driven HR

To reduce the potential liability of a sexual harassment suit, managers should:

-

▪ Establish a written policy prohibiting harassment.

-

▪ Communicate the policy and train employees in what constitutes harassment.

-

▪ Screen potential employees before hiring to make sure they do not have a history of sexually harassing others.

-

▪ Establish an effective complaint procedure.

-

▪ Quickly investigate all claims.

-

▪ Take remedial action to correct past harassment.

-

▪ Make sure that the complainant does not end up in a less desirable position if he or she needs to be transferred.

-

▪ Follow up to prevent continuation of harassment.

Recent U.S. Supreme Court sexual harassment rulings directly affect employer liability in sexual harassment cases. First, an employer may be held liable for the actions of supervisors toward their subordinate employees even if the offense is not reported to top management. Second, the Supreme Court has established an employer defense against sexual harassment claims. The employer must prove two items: (1) It exercised reasonable care to prevent and correct sexual harassment problems in a timely manner,40 and (2) the plaintiff failed to use the internal procedures for reporting sexual harassment.41

If the employee reasonably believes that reporting the offensive conduct is not a viable option, then the employer cannot take advantage of the defense. The internal procedures, then, must consist of fair investigations.42 The Manager’s Notebook entitled “How to Handle a Sexual Harassment Investigation ” provides some guidelines.

MANAGER’S NOTEBOOK How to Handle a Sexual Harassment Investigation

![]() Customer-Driven HR

Customer-Driven HR

Failure to investigate a sexual harassment complaint can result in an employer liability if the case goes to court. Here are some guidelines for conducting an investigation into sexual harassment:

-

▪ Timeliness Managers should respond quickly, within 24 to 48 hours of a complaint of sexual harassment. Reacting later than that risks a charge of negligence.

-

▪ Documentation Managers should ask open-ended questions to get as much detail as possible about the harassment. Notes taken during the interview should be rewritten or typed after the meeting is concluded. The manager should write the report based on notes from the interview with the complainant.

-

▪ Employee agreement After documenting the facts in the report, the manager should go over the events with the complainant and document the employee’s agreement with the report.

-

▪ Resolution Managers should ask what end result the employee is seeking. Those with a genuine complaint usually say they want the harassment to stop. Those with a personal vendetta are often looking to have the alleged perpetrator fired.

-

▪ Findings of fact The manager should interview witnesses who can corroborate or discredit the allegations of sexual harassment. The manager should then interview the alleged harasser. The accused should have the opportunity to defend himself or herself. A “findings of fact” document should be recorded to represent all the facts in the complaint; when this document is completed, the investigation is considered completed.

-

▪ Remedy The employer is obligated only to take steps reasonably likely to stop the harassment and has the right to determine an appropriate course of action. An effective sexual harassment policy gives managers the flexibility to choose from a range of various sanctions, from a written warning to the harasser to stop, to a transfer or demotion, to termination of the harasser.

To safeguard against sexual harassment claims, experts recommend that employers develop a zero-tolerance sexual harassment policy, successfully communicate the policy to employees, and ensure that victims can report abuses without fear of retaliation.43 Furthermore, proactive companies schedule sexual harassment training workshops with mandatory attendance required for all employees. Sexual harassment workshops explain what sexual harassment behaviors look like with role plays or video clips, explain how the company policy works for reporting sexual harassment incidents, and offer opportunities for employees to ask questions. For example, a state law in California requires all employees with supervisory responsibilities in firms with more than 50 employees to take two hours of sexual harassment training at two year intervals.44

The Civil Rights Act of 1991

In 1991, believing that the Supreme Court was beginning to water down Title VII, Congress passed a comprehensive set of amendments to it. Together, these amendments are known as the Civil Rights Act of 1991. Although the legal aspects of these amendments are fairly technical, their impact on many organizations is very real. Among the most important effects of the 1991 amendment are:

-

▪ Burden of proof As we noted earlier, the employer bears the burden of proof in a discrimination case. Once the applicant or employee files a discrimination case and shows some justification for it, the organization has to defend itself by proving that it had a good job-related reason for the decision it made. This standard was originally established in the Griggs v. Duke Power decision in 1971. Then a 1989 Supreme Court case, Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Antonio, had the effect of placing more of the burden of proof on the plaintiff.45 The 1991 law reinstates the Griggs standard.

-

▪ Quotas To avoid adverse impact, many organizations (including the Department of Labor) had developed a policy of adjusting scores on employment tests so that a certain percentage of protected-class applicants would be hired. The 1991 law amending Title VII prohibits quotas , which are employer adjustments of hiring decisions to ensure that a certain number of people from a certain protected class are hired. Thus, quotas, which had received mixed reviews in Supreme Court decisions before 1991, are now explicitly forbidden. Employers that have an affirmative action program giving preference to protected-class candidates have to walk a very fine line between “giving preference” (which is permissible) and “meeting a quota” (which is forbidden).

-

▪ Damages and jury trials The original Title VII law allowed successful plaintiffs to collect only back pay awards. However, racial minorities were also able to use an 1866 law to collect punitive and/or compensatory damages. Punitive damages are fines awarded to a plaintiff to punish the defendant. Compensatory damages are fines awarded to a plaintiff to compensate for the financial or psychological harm the plaintiff has suffered as a result of the discrimination. The 1991 law extended the possibility of collecting punitive and compensatory damages to persons claiming sex, religious, or disability-based discrimination. Such damages are capped at $50,000 to $300,000, depending on the size of the employer.46 In addition, the law allows plaintiffs to request a trial by jury.

Some believe that by expressly forbidding quotas, the Civil Rights Act of 1991 has prohibited a very useful mechanism for reducing discrimination in employment decisions. Many organizations had found that the best way to prevent adverse impact was to use a combination of quotas and cognitive ability testing. That is, the employer would select a certain percentage of applicants from various groups, and then choose the highest performers on cognitive ability tests from each group. This employment strategy resulted in both the maintenance of a high-quality workforce and greater participation of minorities in that workforce. Yet, by outlawing quotas, the Civil Rights Act of 1991 has prohibited this option.47

Executive Order 11246

Executive orders are policies that the president establishes for the federal government and organizations that contract with the federal government. Executive Order 11246 (as amended by Executive Order 11375) was issued by President Johnson in 1965 and is not part of Title VII. It does, however, prohibit discrimination against the same categories of people that Title VII protects. In addition, it goes beyond the Title VII requirement of no discrimination by requiring covered organizations (firms with government contracts over $50,000 and 50 or more employees) to develop affirmative action programs to promote the employment of protected-class members. For instance, government contractors such as Boeing and Lockheed Martin are required to have active affirmative action programs.

The Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967

The Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) prohibits discrimination against people who are 40 or older. When first enacted in 1967, it protected people aged 40 to 65. Subsequently, it was amended to raise the age to 70, and in 1986 the upper age limit was removed entirely.

The majority of ADEA complaints are filed by employees who have been terminated. For instance, a 57-year-old computerized-control salesman for GE Fanuc Automation was the only employee terminated during a “reduction in force”; he was replaced by six younger sales representatives. He brought a lawsuit, claiming that he was fired because of his age, and a Detroit jury awarded him $1.1 million in damages and lost wages and benefits.48 Employers can also lose lawsuits as a result of ill-informed workplace humor. Employers have lost several age discrimination cases because terminated employees had evidence that supervisors had told jokes about old age.49 One age-discrimination case involved 1,697 former employees laid off by Sprint Nextel and was settled in 2005 for $57 million for the plaintiffs. In 2012, the EEOC received 22,857 complaints of age discrimination.50

An important amendment to the ADEA is the Older Workers Protection Act (OWPA) of 1990, which makes it illegal for employers to discriminate in providing benefits to employees based on age. For example, it would be illegal for employers to provide disability benefits only to employees who are age 60 or younger or to require older employees with disabilities to take early retirement. Another OWPA provision makes it more difficult for firms to ask older workers in downsizing and layoff situations to sign waivers in which they give up their right to any future age-discrimination claims in exchange for a payment.51

Some companies value older employees and develop policies that help older workers extend their working lives. One such company is Deere & Company, an industrial-equipment manufacturer based in Moline, Illinois. About 35 percent of its 46,000 employees are older than 50 years of age and a number are in their 70s. Deere & Company spends a lot of effort incorporating ergonomics into its factories, making jobs less tiring, which enables older employees to stay on the job longer.52 With longer life expectancies, there will be greater numbers of employees who will prefer to keep on working beyond their mid-sixties when they qualify for Social Security retirement income and Medicare benefits. Companies will need to rethink how they design careers for older workers who plan to postpone retirement and remain employed. One approach being used to manage older employees is to treat retirement as a process rather than a sudden event and offer older workers “bridge jobs” that provide a transition between full-time employment and retirement. Mercy Health Systems uses such an approach by giving older employees the opportunity to work on jobs during seasonal periods of high demand and then offer long periods of unpaid leave during which these older employees can retain their benefits.53

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

The most recent of the major EEO laws is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) . Signed into law in 1990 and gradually implemented since then, ADA has three major sections. Title I contains the employment provisions; Titles II and III concern the operation of state and local governments and places of public accommodation such as hotels, restaurants, and grocery stores. The ADA applies to all employers with 15 or more employees.54

The central requirement of Title I of the ADA is as follows:

Employment discrimination is prohibited against individuals with disabilities who are able to perform the essential functions of the job with or without reasonable accommodation.

Three parts of this requirement need definition.

Individuals with Disabilities

For the purposes of ADA, individuals with disabilities are people who have a physical or mental impairment that substantially affects one or more major life activities. Some examples of major life activities are:55

-

▪ Walking

-

▪ Speaking

-

▪ Breathing

-

▪ Performing manual tasks

-

▪ Sitting

-

▪ Lifting

-

▪ Seeing

-

▪ Hearing

-

▪ Learning

-

▪ Caring for oneself

-

▪ Working

-

▪ Reading

Obviously, persons who are blind, hearing impaired, or wheelchair bound are individuals with disabilities. But the category also includes people who have a controlled impairment. For instance, a person with epilepsy is disabled even if the epilepsy is controlled through medication. The impairment must be physical or mental and not due to environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantages. For example, a person who has difficulty reading due to dyslexia is considered disabled, but a person who cannot read because he or she dropped out of school is not. Persons with communicable diseases, including those who are HIV-positive (infected with the virus that causes AIDS), are included in the definition of individuals with disabilities.

The ADA Amendments Act (ADAAA) of 2008 is a law that added amendments to the ADA and broadened the definition of a disability so that it is considered to be less than substantially limiting and more than moderately limiting to one or more major life activities. The ADAAA adds more life activities for consideration and includes activities such as bending and communicating, and also includes bodily functions such as immune system, bladder, circulatory, endocrine, neurological, and digestive functions.56 Under the ADAAA, AutoZone was taken to court when it failed to provide a reasonable accommodation for a disabled sales manager who was unable to perform what the court deemed as non-essential job functions (mopping floors and other cleaning tasks) due to back and neck impairments. Even after AutoZone was provided evidence of these impairments, it refused to provide an accommodation and ordered the employee to continue performing cleaning activities that led to additional injury and the need for medical leave. The court awarded the employee a $600,000 settlement and the possibility of obtaining additional back pay.57

In addition, the ADA protects persons who are perceived to be disabled. For instance, an employee might suffer a heart attack. When he tries to return to work, his boss may be scared that the workload will be “too much” and refuses to let him come back. The employer would be in violation of the ADA because he perceives the employee as disabled and is discriminating against him on the basis of that perception.

Two particular classes of people are explicitly not considered disabled: individuals whose current use of alcohol is affecting their job performance and those who use illegal drugs (whether they are addicted or not). However, those who are recovering from their former use of either alcohol or drugs are covered by ADA.

Individuals who are considered morbidly obese, defined as weighing 100 or more pounds above their ideal body weight, may or may not be covered under the ADA. Currently, 9 million U.S. adults are morbidly obese, and many suffer from medical conditions such as hypertension, heart disease, stroke, cancer, depression, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and diabetes. Recent court cases do not consider morbid obesity to be an inherently ADA-eligible condition. To be eligible for ADA coverage, an individual’s morbid obesity would require a physiological cause. The individual making a case for ADA coverage would need to provide medical evidence to the employer that he or she was overweight due to physiological causes. For example, if a medical examination revealed that a person was morbidly obese because of overeating and lack of exercise, the employer would be able to deny ADA coverage to the employee seeking it.58

Intellectual Disabilities

In 2005, the EEOC provided guidelines to address challenges faced by employers in hiring, accommodating, and preventing harassment of employees with intellectual disabilities. The EEOC estimates that within the United States about 2.5 million individuals have intellectual disabilities that occur when: (1) the person’s intellectual function level (IQ) is below 70–75; (2) the person has significant limitations in adaptive skill areas as expressed in conceptual, social, and practical adaptive skills; and (3) the disability originated before the age of 18. Adaptive skills are the basic skills needed for everyday life. They include communication; self-care; home living; social skills; leisure; health and safety; self-direction; functional academics (reading, writing, basic math); and work.59

Not everyone with an intellectual impairment is covered by the ADA. An individual’s intellectual impairment must substantially limit one or more major life activities, such as walking, seeing, hearing, thinking, speaking, learning, concentrating, performing manual tasks, caring for oneself, and working. The following is an example of someone who has an intellectual impairment that would be covered under the ADA:

An individual with an intellectual impairment is hired as part of a crew of employees that works at a concession stand at a movie theater. He helps stock the counter with candy and snacks; at closing time, he cleans the counters and equipment and restocks the concession stand with supplies. However, he cannot perform the function of accurately counting money at closing time, nor is he capable of accurately making change for customers from the cash register. This individual is limited in his intellectual ability to perform basic math skills and therefore has a disability that qualifies for ADA coverage.

Essential Functions

The EEOC separates job duties and tasks into two categories: essential and marginal. Essential functions are job duties that every employee must do or must be able to do to be an effective employee. Marginal functions are job duties that are required of only some employees or that are not critical to job performance. The following examples illustrate the difference between essential and marginal functions:

-

▪ A company advertises a position for a “floating” supervisor to substitute when regular supervisors on the day, night, and graveyard shifts are absent. The ability to work any time of the day or night is an essential job function.

-

▪ A company wishes to expand its business with Japan. In addition to sales experience, it requires all new hires to speak fluent Japanese. This language skill is an essential job function.

-

▪ In any job requiring computer use, it is essential that the employee have the ability to access, input, or retrieve information from the computer terminal. However, it may not be essential that the employee be capable of manually entering or visually retrieving information because technology exists for voice recognition input and auditory output.

-

▪ A group of chemists working together in a lab may occasionally need to answer the telephone. This is considered a marginal job duty because if not every one of the chemists can answer the phone, the other chemists can do so.

ADA requires that employers make decisions about applicants with disabilities solely on the basis of their ability to perform essential job functions. Thus, an employer should not make preemployment inquiries about a job candidate’s disability, although an employer may ask questions about the job candidate’s ability to perform essential job functions.

Reasonable Accommodation

Organizations are required to take some reasonable action to allow employees with disabilities to work for them. The major aspects of this requirement are:

-

▪ Employers must make reasonable accommodation for the known disabilities of applicants or employees so that people with disabilities enjoy equal employment opportunity.60 For example, an applicant who uses a wheelchair may need accommodation if the interviewing site is not wheelchair accessible.

-

▪ Employers cannot deny a person with disabilities employment to avoid providing the reasonable accommodation, unless providing the accommodation would cause an “undue hardship.” Undue hardship is a highly subjective determination, based on the cost of the accommodation and the employer’s resources. For instance, an accommodation routinely provided by large employers (such as specialized computer equipment) may not be required of small employers because the small employers do not have the large employer’s financial resources.

-

▪ No accommodation is required if the individual is not otherwise qualified for the position.

-

▪ It is usually the obligation of the disabled individual to request the accommodation.

-

▪ If the cost of the accommodation would create an undue hardship for the employer, the disabled individual should be given the option of providing the accommodation. For instance, if a visually impaired person applies for a computer operator position in a small company that cannot afford to accommodate the applicant, then the applicant should be given the option to provide the accommodating technology. (Note, though, that the President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities reports that 20 percent of accommodations do not cost anything at all, and less than 4 percent cost more than $5,000.61)

A wide variety of accommodations is possible, and they can come from some surprising sources. For example, Kreonite, Inc., a small family-owned business of about 250 employees that manufactures specialized photographic film, has been committed to employing persons with disabilities and has several employees who are deaf. Kreonite turned to a local not-for-profit training center for someone to teach sign language to its hearing employees. The training was free, and 30 Kreonite employees volunteered to attend.62

Some additional examples of potential reasonable accommodations that the EEOC has suggested are reassigning marginal job duties, modifying work schedules, modifying examinations or training materials, providing qualified readers and interpreters, and permitting use of paid or unpaid leave for treatment.63 An accommodation the EEOC has suggested for people with intellectual disabilities is to provide a job coach on a temporary basis to assist in training the employee to perform the essential functions of the job.64

As we noted earlier in the chapter, the main focus of the ADA and its accompanying regulations is the hiring process. However, the majority of complaints filed so far involve situations in which current employees have become disabled on the job. According to the EEOC, the total number of disability cases filed under the ADA in 2009 was 21,451. The two largest categories of cases were emotional and psychiatric impairments and back injuries, both of which are difficult to diagnose and treat.65 Managers need to be prepared to deal with a set of issues not anticipated by the lawmakers and regulators who created and passed the ADA.

The Vocational Rehabilitation Act of 1973

The Vocational Rehabilitation Act is the precursor to the ADA. However, this act applies only to the federal government and its contractors. Like Executive Order 11246, the Vocational Rehabilitation Act not only prohibits discrimination (in this case, on the basis of disability), but also requires that the covered organizations have an affirmative action plan to promote the employment of individuals with disabilities. Familiarity with this law is useful to organizations attempting to comply with the ADA because it has led to over 30 years’ worth of court and regulatory decisions based on the same central prohibition against disability-based discrimination.

The Vietnam ERA Veterans Readjustment Act of 1974

One additional EEO law deserves brief mention. The Vietnam Era Veterans Readjustment Act of 1974 prohibits discrimination against Vietnam-era veterans (those who served in the military between August 5, 1964, and May 7, 1975) by federal contractors. The law also protects the rights of military veterans who served on active duty during a war, campaign, or expedition for which a campaign badge has been authorized, which includes subsequent military campaigns such as the Gulf War (1991), the war in Iraq (2003–2011), and the war in Afghanistan (2001–2015). It also requires federal contractors to take affirmative action to hire Vietnam-era veterans and those from more recent campaigns.