5. Moving Target

ISO 100 • 0.3 sec. • f/22 • 17mm lens

How to Shoot When Your Subject Is in Motion

Now that you have learned about the professional modes, it’s time to put your newfound knowledge to good use. Whether you are shooting the action at a professional sporting event or a child on a merry-go-round, you’ll learn techniques that will help you bring out the best in your photography when your subject is in motion.

The number one thing to know when trying to capture a moving target is that speed is king! I’m not talking about how fast your subject is moving but rather how fast your shutter is opening and closing. Shutter speed is the key to freezing the moment in time—but also to conveying movement. It’s all about intentions. If you want to freeze motion, then you’ll want to use a fast shutter speed, but if you want to show motion, then you’ll want to use a slower shutter speed. There are some other considerations for taking your shot to the next level, too: composition, lens selection, and a few more items that we will explore in this chapter. So strap on your seat belt and hit the gas, because here we go!

Poring Over the Picture

I’m a huge fan of cycling, and shooting the sport is a great way to flex your action photography muscle. Criterium races (crits for short) are nice events to shoot because they take place on shorter courses. I was able to walk to many vantage points during this race and think creatively in a small space about the shots I got. As much as I like to create images of moving subjects facing the camera (more on that later in the chapter), I was struck by the energy that this shot conveyed with its shallow depth of field and composition.

ISO 100 • 1/6400 sec. • f/2.8 • 85mm lens

Stop Right There!

Shutter speed is the main tool in the photographer’s arsenal for capturing great action shots. The ability to freeze a moment in time often makes the difference between a good shot and a great one. To take advantage of this concept, you should have a solid grasp of the relationship between shutter speed and movement. When you press the shutter release button, your camera goes into action by opening the shutter curtain and then closing it after a predetermined length of time. The longer you leave your shutter open, the more your subject will move across the frame, so common sense dictates that the first thing to consider is just how fast your subject is moving.

Typically, you will be working in fractions of a second. How many fractions depends on several factors. Subject movement, while simple in concept, is actually based on three factors. The first is the direction of travel. Is the subject moving across your field of view (left to right) or traveling toward or away from you? The second consideration is the actual speed at which the subject is moving. There is a big difference between a moving sports car and a child on a bicycle. Finally, the distance from you to the subject has a direct bearing on how fast the action seems to be taking place. Let’s take a brief look at each of these factors to see how they might affect your shooting.

Direction of travel

Typically, the first thing people think about when taking an action shot is how fast the subject is moving, but the first consideration should actually be the direction of travel. Where you are positioned in relation to the subject’s direction of travel is critical in selecting the proper shutter speed. When you open your shutter, the lens gathers light from your subject and records it on the camera sensor. If the subject is moving across your viewfinder, you need a faster shutter speed to keep that lateral movement from being recorded as a streak across your image. Subjects that are moving perpendicular to your shooting location do not move across your viewfinder and appear to be more stationary. This allows you to use a slightly slower shutter speed (Figure 5.1). A subject that is moving in a diagonal direction—both across the frame and toward or away from you—requires a shutter speed in between the two.

ISO 800 • 1/500 sec. • f/2.8 • 110mm lens

Figure 5.1 Action coming toward the camera can be captured with slower shutter speeds. However, it’s always a good idea to shoot with as fast a shutter speed as possible when you want to freeze the action. My oldest daughter isn’t racing her bicycle anytime soon, but I used a shutter speed fast enough to freeze the action no matter what!

Subject speed

Once the angle of motion has been determined, you can then assess the speed at which the subject is traveling. The faster your subject moves, the faster your shutter speed needs to be in order to “freeze” that subject (Figure 5.2). A person walking across your frame might only require a shutter speed of 1/60 of a second, while a horse trotting in the same direction would call for 1/500 of a second. That same horse traveling toward you at the same rate of speed, rather than across the frame, might only require a shutter speed of 1/125 of a second. You can start to see how the relationship of speed and direction comes into play in your decision-making process.

ISO 200 • 1/4000 sec. • f/2.8 • 200mm lens

Figure 5.2 I stepped out of my hostel one early morning in Rotorua, New Zealand, only to spend the next hour watching this horse and rider make laps around the track. Even though they were a fair distance from me, I used the fastest shutter speed possible to freeze the action (and even the dirt flying up behind them).

Subject-to-camera distance

So now we know both the direction and the speed of your subject. The final factor to address is the distance between you and the action. Picture yourself looking at a highway full of cars from up in a tall building a quarter of a mile from the road. As you stare down at the traffic moving along at 55 miles per hour, the cars and trucks seem to be slowly moving along the roadway. Now picture yourself standing in the median of that same road as the traffic flies by at the same rate of speed; it appears to be moving much faster.

Although the traffic is moving at the same speed, the shorter distance between you and the traffic makes the cars look as if they are moving much faster. This is because your field of view is much narrower; therefore, the subjects are not going to present themselves within the frame for the same length of time. The concept of distance applies to the length of your lens as well (Figure 5.3). If you are using a wide-angle lens, you can probably get away with a slower shutter speed than if you were using a telephoto, which puts you in the heart of the action. It all has to do with your field of view. That telephoto gets you “closer” to the action—and the closer you are, the faster your subject will be moving across your viewfinder.

ISO 100 • 1/2000 sec. • f/5.6 • 200mm lens

Figure 5.3 Due to the distance from the camera, a slower shutter speed could be used to capture this action. Given the time of day (mid-morning) and not needing a wide depth of field, I used a fairly open aperture to achieve a fast shutter speed and freeze the parachute and passengers in tow above the mountain range.

Using Shutter Priority (S) Mode to Stop Motion

In Chapter 4, you were introduced to the professional shooting modes. As discussed there, the mode that gives you ultimate control over shutter speed is Shutter Priority, or S, mode, where you are responsible for selecting the shutter speed while handing over the aperture selection to the camera. The ability to concentrate on just one exposure factor helps you quickly make changes on the fly while staying glued to your viewfinder and your subject.

There are a couple of things to consider when using Shutter Priority mode, both of which have to do with the amount of light that is available when shooting. While you have control over which shutter speed you select in Shutter Priority mode, the range of shutter speeds that is available to you depends largely on how well your subject is lit.

Typically, when shooting fast-paced action, you will be working with very fast shutter speeds. This means that your lens will probably be set to a large aperture. If the light is not sufficient for the shutter speed selected, you will need to do one of two things: Select a lens that offers a larger working aperture, or raise the ISO of the camera.

Working off the assumption that you have only one lens available, let’s concentrate on balancing your exposure using the ISO.

Let’s say that you are shooting a baseball game at night, and you want to get some great action shots. You set your camera to Shutter Priority mode and, after testing out some shutter speeds, determine that you need to shoot at 1/500 of a second to freeze the action on the field. When you place the viewfinder to your eye and press the shutter button halfway, you notice that the f-stop blinks. This is your camera’s way of telling you that the lens has now reached its maximum aperture and you are going to be underexposed if you shoot your pictures at the currently selected shutter speed. You could slow your shutter speed down until the blinking f-stop goes away, but then you could get images with too much motion blur.

The alternative is to raise your ISO to a level that is fast enough for a proper exposure. The key here is to always use the lowest ISO that you can get away with. That might mean ISO 100 in bright sunny conditions or ISO 3200 for an indoor or night situation (Figure 5.5).

ISO 3200 • 1/400 sec. • f/2.8 • 200mm lens

Figure 5.5 Even though the city aquatic center’s lights were bright to the eye, I needed to significantly raise the ISO to freeze champion diver Jennifer Mangum as she left the platform.

Just remember that the higher the ISO, the greater the amount of noise in your image. This is the reason that you see professional sports photographers using those mammoth lenses perched atop a monopod: They could use a smaller lens, but to get a very large aperture they need a huge piece of glass on the front of the lens. The larger the glass on the front of the lens, the more light it gathers, and the larger the aperture for shooting. For the working pro, the large aperture translates into low ISO (and thus low noise), fast shutter speeds, and razor-sharp action. But you’re in luck: The D7200 has very low noise at higher ISOs, so feel free to increase the ISO so you can get those shots you might otherwise miss.

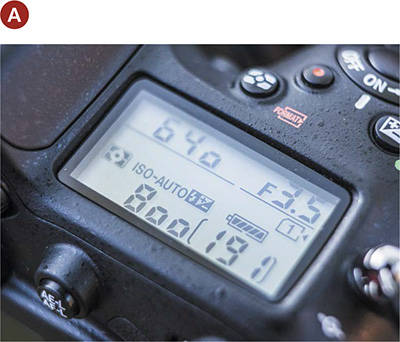

Adjusting your ISO on the fly

1. Look at the exposure values (the shutter speed and aperture settings) in the lower portion of your viewfinder.

2. If you’re unable to achieve a fast shutter speed, then it’s time to increase the ISO.

3. Select the higher ISO by observing the control panel (A) while pressing and holding the ISO button on the back of the camera and rotating the main Command dial to the right. Once the desired ISO is selected, simply release the ISO button (B).

4. Now observe the shutter speed and the Exposure indicator to determine if the desired speed and exposure have been achieved. Repeat steps 2–4 until optimum speed and exposure have been achieved.

Using Aperture Priority (A) Mode to Isolate Your Subject

One of the benefits of working in Shutter Priority mode with fast shutter speeds is that, more often than not, you will be shooting with the largest aperture available on your lens. Shooting with a large aperture allows you to use faster shutter speeds, but it also narrows your depth of field.

To isolate your subject in order to focus your viewer’s attention on it, a larger aperture is required. The larger aperture reduces the foreground and background sharpness: the larger the aperture, the more blurred the foreground and background will be.

The reason that I bring this up here is that when you are shooting most sporting events, the idea is to isolate your main subject by having it in focus while the rest of the image has some amount of blur. This sharp focus draws your viewer right to the subject. Studies have shown that the eye is drawn to sharp areas before moving on to the blurry ones. Also, depending on what your subject matter is, a busy background can be distracting if everything in the photo is equally sharp. Without a narrow depth of field, it might be difficult for the viewer to establish exactly what the main subject is in your picture.

Let’s look at how to use depth of field to bring focus to your subject. In the previous section, I told you that you should use Shutter Priority mode for getting those really fast shutter speeds to stop action. Generally speaking, Shutter Priority mode will be the mode you most often use for shooting sports and other action, but at times you’ll want to ensure that you are getting the narrowest depth of field possible in your image. The way to do this is by using Aperture Priority mode, or A.

So how do you know when you should use Aperture Priority mode as opposed to Shutter Priority mode? There’s no simple answer, but your LCD can help you make this determination. The best scenario for using Aperture Priority mode is a brightly lit scene where maximum apertures will still give you plenty of shutter speed to stop the action.

Let’s say that you are shooting a football game in the midday sun. If you have determined that you need something between 1/500 and 1/1250 of a second for stopping the action, you could just set your camera to a high shutter speed in Shutter Priority mode and start shooting. But you also want to be using an aperture of, say, f/4.5 to get that narrow depth of field. Here’s the problem: If you set your camera to Shutter Priority mode and select 1/1000 of a second as a nice compromise, you might get that desired f-stop—but you might not. As the meter is trained on your moving subject, the light levels could rise or fall, which might actually change that desired f-stop to something higher like f/5.6 or even f/8. Now the depth of field is extended, and you will no longer get that nice isolation and separation that you wanted.

To rectify this, switch the camera to Aperture Priority mode and select f/4.5 as your aperture. Now, as you begin shooting, the camera holds that aperture and makes exposure adjustments with the shutter speed. As I said before, this works well when you have lots of light—enough light so that you can have a high enough shutter speed without introducing motion blur.

The ISO Sensitivity Auto Control Trick

There is a very cool trick that can get you the best of both worlds and that won’t sacrifice your shutter speed or aperture. With the ISO Sensitivity auto control feature, you can set the camera to automatically select an ISO that keeps you at your preferred shutter speed, while using the largest aperture and lowest ISO possible. It will also put an upper limit on the ISO to keep you from getting too much noise in your images, but as I mentioned before, the D7200 has some of the best low-noise performance on the market.

Here’s the way it works. If I am shooting an activity that requires a shutter speed of 1/250 of a second, I set that as the minimum in the auto control settings. Then I decide that I can deal with the noise that is produced with an ISO up to 3200, so I set that as my maximum sensitivity. Since I would always like to use the lowest ISO, I set the low ISO sensitivity to 100. Once everything is set, the camera will now adjust my ISO without any interaction from me, letting me shoot at my desired shutter speed at the lowest possible ISO and largest aperture setting possible.

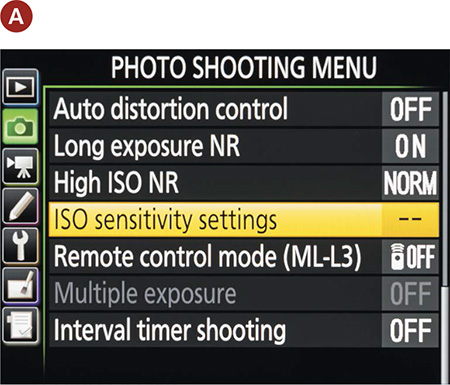

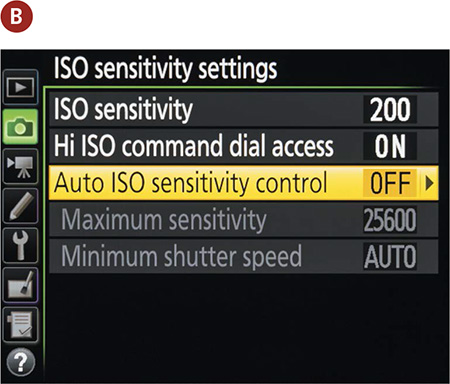

Setting up the ISO Sensitivity auto control feature

1. Press the Menu button and then use the Multi-selector to scroll down to the Photo Shooting menu.

2. Press the OK button on the Multi-selector to enter the menu and then locate the ISO Sensitivity Settings feature (A).

3. Press the Multi-selector to the right to enter the setup screen.

4. Press OK on the Multi-selector to select the lowest ISO that you wish to use (ISO Sensitivity), and press the OK button.

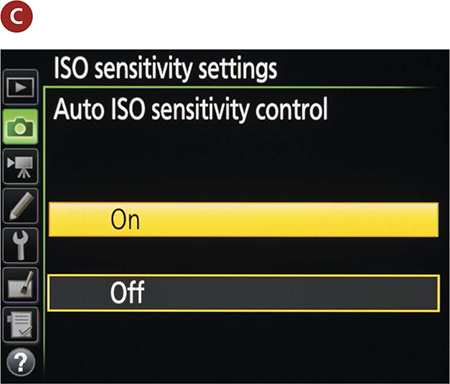

5. Press the Multi-selector down to highlight Auto ISO Sensitivity Control (B) and then select On to activate the feature (C).

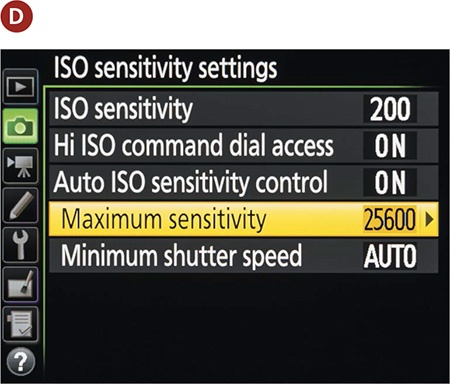

6. Use the Multi-selector to choose Maximum Sensitivity (D). This will be the upper limit of your ISO.

7. Finally, select the Minimum Shutter Speed that you want to use while shooting (E). This will be completely dependent on the speed necessary to stop the action you are shooting.

With everything set up, you can begin shooting without fear of constantly having to change the ISO. This technique is also quite helpful when working in varying light conditions. As you are shooting, you will notice the ISO-Auto warning in the lower-right portion of the viewfinder along with the adjusted ISO setting.

Keep Them in Focus with Continuous-servo Focus and AF Focus Point Selection

With the exposure issue handled for the moment, let’s move on to something equally important: focusing. If you have browsed your manual, you know that you have several focus modes to choose from in the D7200. To get the greatest benefit from each of them, it is important to understand how they work and the situations in which each mode will give you the best opportunity to grab a great shot. Because we are discussing subject movement, our first choice is going to be Continuous-servo AF mode (AF-C). AF-C mode uses all of the focus points in the camera to find a moving subject and then lock in the focus when the shutter button is completely depressed.

Selecting and shooting in Continuous-servo AF focus mode

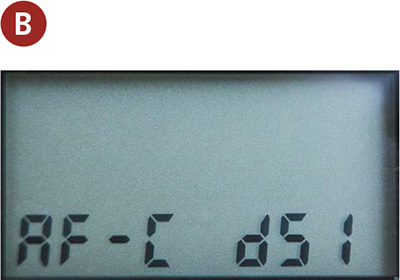

1. Ensure that the Focus-mode selector is switched to AF, and press and hold the AF-mode button while observing the control panel (A).

2. Now rotate the main Command dial while continuing to hold the AF button. Once you have selected AF-C, release the AF-mode button.

The camera will maintain the subject’s focus as long as it remains within one of the focus points in the viewfinder or until you release the shutter button or take a picture.

Note that holding down the shutter button for long periods of time will cause your battery to drain much faster because the camera will be constantly focusing on the subject.

When using the AF-C mode, you can use the AF point mode set to Dynamic Area, which makes a focus point of your choosing the primary focus but uses information from the surrounding points if your subject happens to move away from the point.

Setting the AF-area mode to Dynamic

1. To set the AF-area mode, press and hold the AF-mode button on the front of the camera while observing the control panel.

2. Now rotate the Sub-command dial while holding the AF-mode button (A). As you turn the dial, your AF modes will be displayed on the control panel. Select from one of three dynamic modes and release the AF-mode button when you have made your selection (B).

Note that the AF mode is used to select the method with which the camera will focus the lens. This is different from the AF point, which is a cluster of small points that are visible in the viewfinder and are used to determine where you want the lens to focus.

Stop and Go with 3D-tracking AF

If you are going to be changing between a moving target and one that is still, you should consider using the 3D-tracking AF mode. The 3D mode uses a color signature to help track the subject with the help of all 51 AF points. This system works very well when the subject’s color is different than that of the background.

When you have a stationary subject, simply place your selected focus point on your subject and the camera will focus on it. If your subject begins to move out of focus, the camera will track the movement, keeping a sharp focus.

For example, suppose you are shooting a football game. The quarterback has brought the team to the line and he is standing behind the center, waiting for the ball to be hiked. If you are using the 3D-tracking AF mode, you can place your focus point on the quarterback and start taking pictures of him as he stands at the line. As soon as the ball is hiked and the action starts, the camera will switch to tracking mode and follow his movement within the frame. This can be a little tricky at first, but once you master it, it will make your action shooting effortless.

To select 3D-tracking, simply follow the same steps listed for selecting Dynamic modes but instead select the 3D-tracking mode. It is important to know that the 3D-tracking AF mode uses color and contrast to locate and then follow the subject, so this mode might be less effective when everything is similar in tone or color.

Manual Focus for Anticipated Action

Although I use the automatic focus modes for the majority of my shooting, there are times when I like to fall back on manual focus. This is usually when I know when and where the action will occur and I want to capture the subject as it crosses a certain plane of focus. This is useful in racing and other sports where the subjects are on a defined path and I know exactly where I want to capture the action. I could try tracking the subject, but sometimes the view can be obscured by a curve in the track or a highly contrasting background. By prefocusing the camera, all I have to do is wait for the subject to approach my point of focus (Figure 5.6) and then start firing the camera.

ISO 3200 • 1/500 sec. • f/2.8 • 145mm lens

Figure 5.6 For this image of Jennifer Mangum, I needed to manually focus where I knew she would be in her dive. Autofocus would grab the stands in the background and possibly miss the diving action at this precise moment. Anticipating where your subject will be is a major advantage when capturing motion.

It is also a good idea to decide how much of the environment you want to show in your image. On this section of a mountain bike race, I wanted to bring attention to the vertical lines of the dormant trees surrounding the trail. I could have cropped in tighter for a more traditional sports shot of the racer, but I would have lost the essential background information (Figure 5.7).

ISO 800 • 1/8000 sec. • f/2.8 • 17mm lens

Figure 5.7 You don’t always need to crop in tight on a motion shot. By showing more of the environment, I was able to give the viewer a sense of time and place. I also pre-composed (and focused) the shot to block the bald sun with a tree.

Keeping Up with the Continuous Shooting Modes

Getting great focus is one thing, but capturing the best moment on the sensor can be difficult if you are shooting just one frame at a time. In the world of sports, and in life in general, things move pretty fast. If you blink, you might miss it. The same can be said for shooting in Single Frame mode. Fortunately, your D7200 comes equipped with a Continuous High (CH) shooting—or “burst”—mode that lets you capture a series of images at up to six frames a second (Figure 5.8). You can also select Continuous Low (CL), which allows the user to customize the desired frames per second by using the Custom Settings.

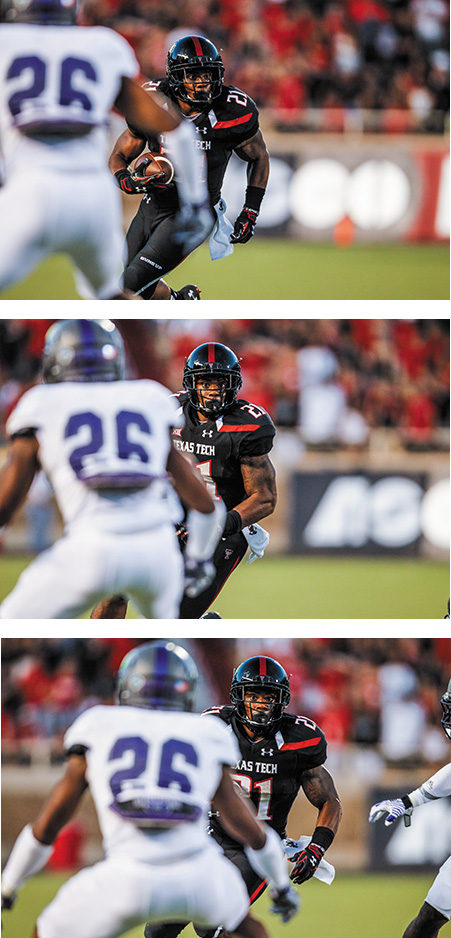

ISO 1600 • 1/1250 sec. • f/2.8 • 400mm lens

Figure 5.8 Using a continuous release mode means that you are sure to capture the peak of the action. Using the continuous shooting mode causes the camera to keep taking images for as long as you hold down the shutter release button. In Single Frame mode, you have to release the button and then press it again to take another picture.

Setting up and shooting in a continuous release mode

While pressing the Release Mode dial lock simply turn the Release Mode dial to either CL or CH. CH will provide up to six frames per second (five if you are shooting RAW), and CL will provide one to six frames per second, based upon the user’s preference. To set up CL, go to D2 in your Custom Settings menu. (For more on this, refer to page 280 of your user manual.)

Your camera has an internal memory, called a “buffer,” where images are stored while they are being processed prior to being moved to your memory card. Depending on the image format you are using, the buffer might fill up, and the camera will stop shooting until space is made in the buffer for new images. The camera readout in the viewfinder tells you how many frames you have available in burst mode. Just look in the viewfinder at the bottom right to see the maximum number of images for burst shooting. As you shoot, the number will go down and then back up as the images are written to the memory card.

A Sense of Motion

Shooting action isn’t always about freezing the action. At times you want to convey a sense of motion so that the viewer can get a feel for the movement and flow of an event. Two techniques you can use to achieve this effect are panning and motion blur.

Panning

Panning has been used for decades to capture the speed of a moving object as it moves across the frame. It doesn’t work well for subjects that are moving toward or away from you. Panning is achieved by following your subject across your frame, moving your camera along with the subject, and using a slower-than-normal shutter speed so that the background (and sometimes even a bit of the subject) has a sideways blur but the main portion of your subject is sharp and blur-free.

The key to a great panning shot is selecting the right shutter speed: too fast and you won’t get the desired blurring of the background; too slow and the subject will be too blurry and will not be recognizable. Practice the technique until you can achieve a smooth motion with your camera that follows along with your subject. The other thing to remember when panning is to follow through even after the shutter has closed. This will keep the motion smooth and give you better images.

Panning can take a lot of practice before you stumble upon the correct shutter speed. I shoot a handful of NCAA football games a year, and I wanted to create a quality pan of Texas Tech’s mascot, the Masked Rider. The horse runs down the field at a swift pace, and I knew from previous tries that I would need a shutter speed that was relatively easy to handhold but slow compared to the subject’s movement. Aided by continuous mode and Shutter Priority, I was able to achieve the perfect shot (Figure 5.9), albeit through trial and error over the course of three games that season.

ISO 100 • 1/50 sec. • f/18 • 50mm lens

Figure 5.9 Following the subject as it moves across your field of view allows for a slower shutter speed and adds a sense of motion. Panning takes practice, so it’s helpful to seek out plenty of opportunities to hone your skills.

Motion blur

Another way to let the viewer in on the feel of the action is to simply include some blur in the image (Figure 5.10). This isn’t accidental blur from choosing the wrong shutter speed. This blur is more exaggerated, and it tells a story (Figure 5.11). In Figure 5.10, I wanted to capture the circular motion of the Ferris wheel and use it as a nicely composed background subject to the foreground carousel. The motion of the Ferris wheel is a second and dynamic visual attraction, only surpassed by the attractive glow of the colors against the evening sky.

ISO 100 • 4 sec. • f/22 • 35mm lens

Figure 5.10 The movement of the Ferris wheel, made evident by a slow shutter speed, creates an engaging composition.

ISO 100 • 15 sec. • f/11 • 30mm lens

Figure 5.11 At a shutter speed of 15 seconds, the water in the marina smooths out and the boats’ masts sway and blur, but the boats stay stationary enough to hold the image’s composition.

Just as in panning, there is no preordained shutter speed to use for this effect. It is simply a matter of trial and error until you have a look that conveys the action. I try to show an area of the frame that is frozen—for instance, in the previous shot of the amusement park, the carousel did not move. In the shot of the boats, the pier and background landscape are locked in place. This helps lend visual contrast and adds to the story of the photo. The key to this technique is the correct shutter speed combined with keeping the camera still during the exposure. You are trying to capture the motion of the subject, not the photographer or the camera, so use a good shooting stance or even a tripod.

Tips for Shooting Action

Give them somewhere to go

Framing your image is as important as how well you expose it. A poorly composed shot can ruin a great moment by not holding the viewer’s attention.

One common mistake in action photography is not using the frame properly. If you are dealing with a subject moving horizontally across your field of view, give the subject somewhere to go by placing it to the side of the frame, with its motion leading toward the middle of the frame (Figure 5.12). This offsetting of the subject will introduce a sense of direction and anticipation for the viewer. Unless you are going to completely fill the image with the action, try to avoid placing your subject in the middle of the frame.

ISO 100 • 1/400 sec. • f/5.6 • 35mm lens

Figure 5.12 Try to leave space in front of your subject to lead the action in a direction. In this case, the straight Ogo paths provide a direction for the eye to travel, ultimately pulling the viewer from the bottom of the frame (and its foreground) to the top (and its background).

Ogo rides in Rotorua, New Zealand, are very popular and fun to photograph. To tell a more complete visual story of what the activity entails, I photographed the Ogo making a steady descent from its point of origin. I used the developed pathway to draw the eye from foreground to midground, indicating where the eye should travel in the frame and, more importantly, giving the spherical amusement ride somewhere to go.

Get in front of the action

Here’s another tip. When shooting action, show the action coming toward you (Figure 5.13) rather than going away from you. People want to see faces. Faces convey the action, the drive, the sense of urgency, and the emotion of the moment. So if you are shooting action involving people, always position yourself so that the action is either coming at you or is at least perpendicular to your position.

ISO 100 • 1/1000 sec. • f/2.8 • 400mm lens

Figure 5.13 Shooting from the front with a telephoto gives a feeling that the action is coming right at you, no matter how fast it is moving. Texas Tech coach Kliff Kingsbury moves toward the camera as the rest of the staff faces away, adding to the visual contrast created by his black shirt on a background of white.

Put your camera in a different place

Changing your vantage point is a great way to find new angles. Shooting from above with a wide-angle lens might let you incorporate some depth into the image. Shooting from farther away with a telephoto lens will compress the elements in a scene and allow you to crop in tighter on the action. Don’t be afraid to experiment and try new things.

Figure 5.14 is shot from inches above the trail. Shooting from this angle conveys a sense of power about the rider. This is a common approach to professional sports photographs, and it is one that can have more visual impact than a shot from the rider’s eye level. Always vary your shooting position.

ISO 200 • 1/2500 sec. • f/4 • 98mm lens

Figure 5.14 Shooting from varied and extreme angles can yield pleasing results.

I could not have achieved this viewpoint if I had not ridden the trail myself earlier that day and noted this angle as a worthy shot. It’s also worth saying, though, that shooting from a low perspective is not the only option. Move around and imagine shooting from higher angles as well. It is better to move about while you are shooting than to stay in one vantage point—it’s nice to have options when it comes to the edit.

Chapter 5 Assignments

The mechanics of motion

For this first assignment, you need to find some action. Explore the relationship between the speed of an object and its direction of travel. Use the same shutter speed to record your subject moving toward you and across your view. Try using the same shutter speed for both to compare the difference made by the direction of travel.

Wide vs. telephoto

Just as with the first assignment, photograph a subject moving in different directions, but this time, use a wide-angle lens and then a telephoto. Check out how the telephoto setting on the zoom lens will require faster shutter speeds than the lens at its wide-angle setting.

Getting a feel for focusing modes

We discussed two different ways to autofocus for action: Dynamic Area and 3D-tracking. Starting with Dynamic Area mode, find a moving subject and use the mode to get familiar with the way the mode works. Now repeat the process using the 3D-tracking AF mode. The point of the exercise is to become familiar enough with the two modes to decide which one to use for the situation you are photographing.

Anticipating the spot using manual focus

For this assignment, you will need to find a subject that you know will cross a specific line on which you can prefocus. A street with moderate traffic works well for this. Manually focus on a spot on the street that the cars will travel across. You need to set the drive mode on the camera to continuous mode. Now, when a car approaches the spot, start shooting. Try shooting in three- or four-frame bursts.

Following the action

Panning is a great way to show motion. To begin, find a subject that will move across your path at a steady speed and practice following it in your viewfinder from side to side. Now, with the camera in Shutter Priority mode, set your shutter speed to 1/30 of a second and the focus mode to Dynamic Area. Now pan along with the subject and shoot as it moves across your view. Experiment with different shutter speeds and focal lengths. Panning is one of those skills that take some time to get a feel for, so try it with different types of subjects moving at different speeds.

Feeling the movement

Instead of panning with the motion, use a stationary camera position and adjust the shutter speed until you get a blurred effect that gives the sense of motion while the subject is still identifiable. There is a big difference between a slightly blurred photo that looks like you just picked the wrong shutter speed and one that looks as if it intends to show motion. Vary your shutter speed to achieve the desired effect.

Share your results with the book’s Flickr group!

Join the group here: flickr.com/groups/nikond7200_fromsnapshotstogreatshots