6. Perfect Portraits

ISO 100 • 1/640 sec. • f/2.8 • 108mm lens

Settings and Features to Make Great Portraits

Some of my favorite things to photograph are environmental portraits. I enjoy tying a person to the context in which they exist. Environmental portraits, though, are only one kind of portrait photography. Taking pictures of people is one of the great joys of photography, and portraiture is one of the most important types of photography. In this chapter, we will explore some camera features and techniques that can help you create great portraits.

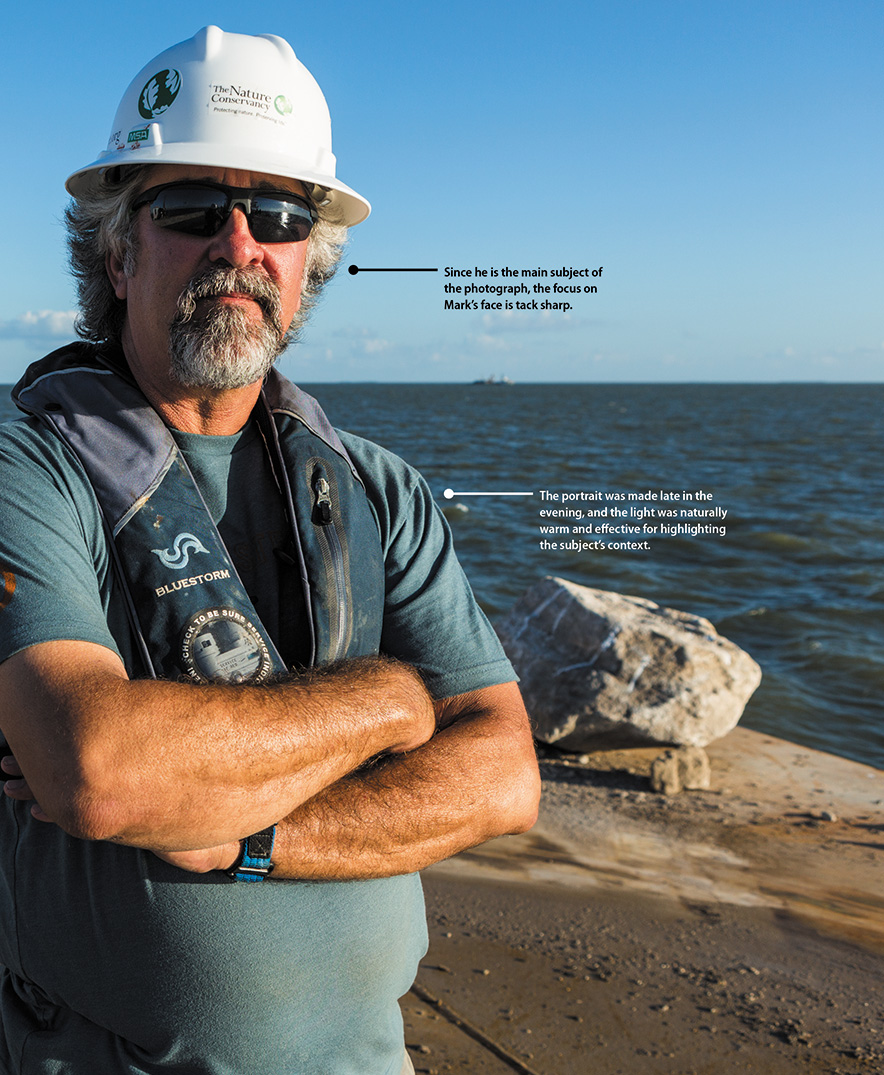

Poring Over the Picture

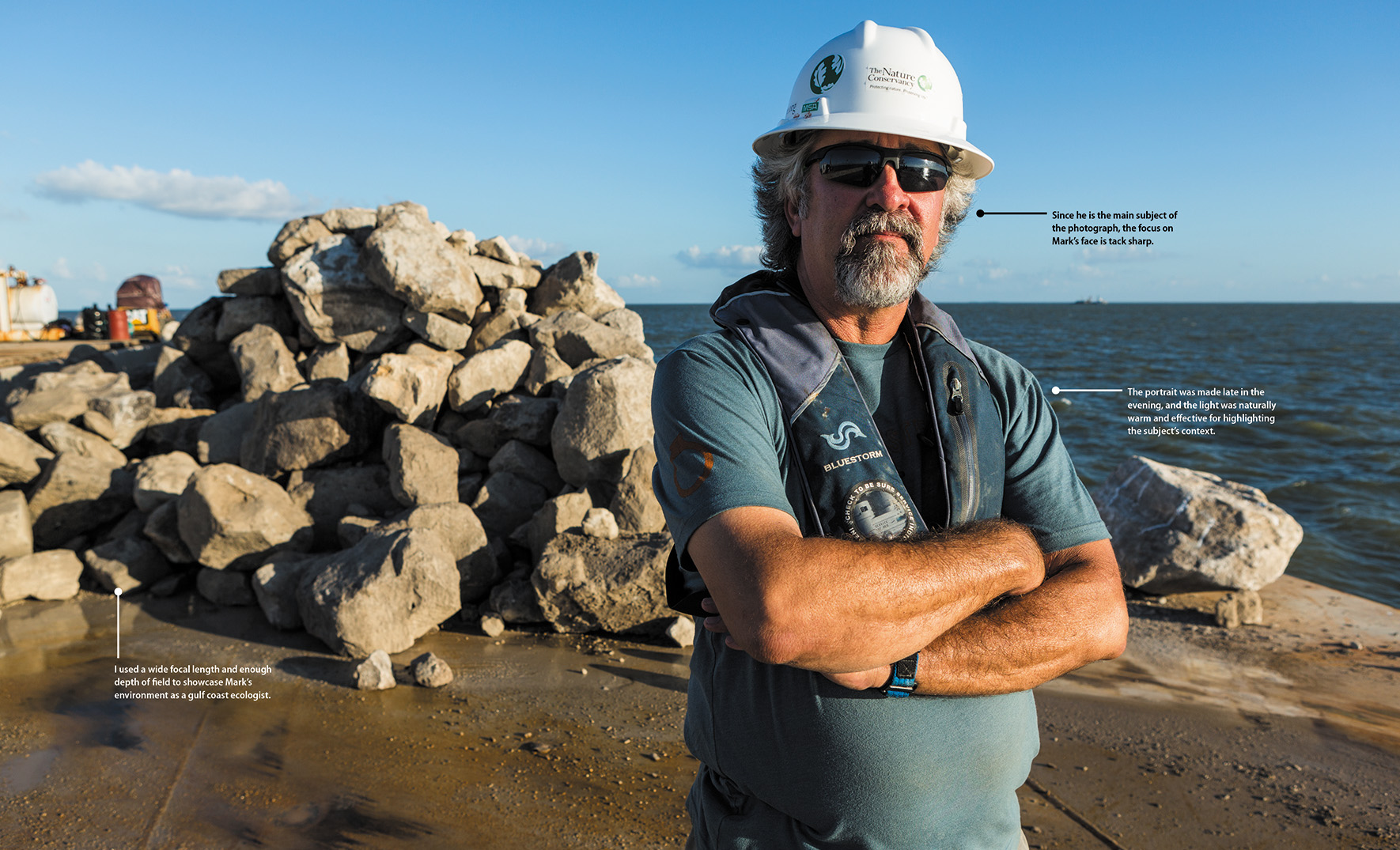

My friend Mark Dumesnil is a project manager for The Nature Conservancy along the Texas Gulf Coast. I recently photographed him aboard a barge loaded with stones that were to be placed in the gulf to restore an oyster reef. Although I was on assignment to photograph the work on the coast, I always take the opportunity to make environmental portraits when the setting and light are right. We happened to meet on the barge, and I took advantage of having the “boss” onboard.

ISO 100 • 1/500 sec. • f/5.6 • 24mm lens

Automatic Portrait Mode

In Chapter 3, we reviewed the automatic scene modes. One of them, Portrait mode, is dedicated to shooting portraits. While this is not my preferred camera setting, it is a great jumping-off point for those who are just starting out. The key to using this mode is to understand what is going on with the camera so that when you venture further into portrait photography, you can expand on the settings and get the most from your camera and, more importantly, your subject.

Whether you are photographing an individual or a group, the emphasis should always be on the subject. Portrait mode uses a larger aperture setting to keep the depth of field very narrow, which means that the background will appear slightly blurred or out of focus. To take full advantage of this effect, use a medium- to telephoto-length lens. Also, keep a pretty close distance to your subject. If you shoot from too far away, the narrow depth of field will not be as effective.

Using Aperture Priority Mode

If you took a poll of portrait photographers to see which shooting mode was most often used for portraits, the answer would certainly be Aperture Priority (A, for short) mode. Selecting the right aperture is important for placing the most critically sharp area of the photo on your subject while simultaneously blurring all of the distracting background clutter (Figure 6.1). Not only will a large aperture give the narrowest depth of field, but it will also allow you to shoot in lower light levels at lower ISO settings.

ISO 100 • 1/160 sec. • f/2.8 • 70mm lens

Figure 6.1 Using a wide aperture, especially with a longer lens, blurs distracting—albeit colorful—background details.

This isn’t to say that you have to use the largest aperture on your lens. An aperture of f/1.4 may be too large, thus creating an extremely shallow depth of field. A good place to begin is f/5.6. This will give you enough depth of field to keep the entire face in focus, while providing enough blur to eliminate distractions in the background. This isn’t a hard-and-fast setting; it’s just a good all-around number to start with. Your aperture might change depending on the focal length of the lens you are using and on the amount of blur that you want for your foreground and background elements. Remember that a portrait is all about the eyes, so focus first on the eyes and then recompose the frame if needed (Figure 6.2).

ISO 640 • 1/500 sec. • f/2.8 • 115mm lens

Figure 6.2 Try to connect with the person when you’re taking their photograph. You don’t want them looking away; you want to maintain a good focus on the eyes.

Go wide for environmental portraits

There will be times when your subject’s environment is of great significance to the story you want to tell. This might mean using a smaller aperture to get more detail in the background or foreground. Once again, by using Aperture Priority mode, you can set your aperture to a higher f-stop, such as f/8 or f/11, and include the important details of the scene that surrounds your subject.

Using a wider-than-normal lens can also assist in getting more depth of field as well as showing the surrounding area. A wide-angle lens requires less stopping down of the aperture (making the aperture smaller) to achieve an acceptable depth of field. Wide-angle lenses cover a greater area, so the depth of field appears to cover a greater percentage of the scene.

A wider lens might also be necessary to relay more information about the scenery (Figure 6.3). Select a focal length that is wide enough to tell the story but not so wide that you distort the subject. Few things in the world of portraiture are quite as unflattering as giving someone a big, distorted nose (unless you are going for that sort of look). When shooting a portrait with a wide-angle lens, keep the subject away from the edge of the frame. This will reduce the distortion, especially in very wide focal lengths. As the focal length increases, distortion will be reduced.

ISO 100 • 1/100 sec. • f/16 • 17mm lens

Figure 6.3 I used a wide-angle lens to capture more of the environment surrounding Julie, a biologist focusing on oyster reef restoration in the Gulf of Mexico.

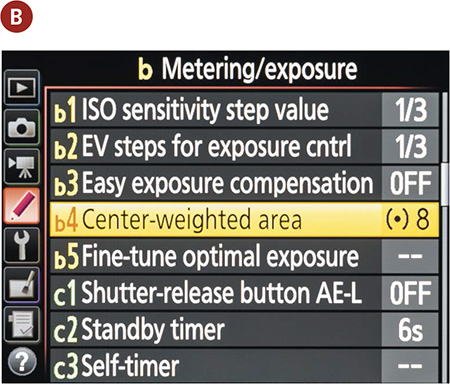

Metering Modes for Portraits

For most portrait situations, Matrix mode will work great. (For more on how metering works, see the “Metering Basics” sidebar.) This mode measures light values from all portions of the viewfinder and then establishes a proper exposure for the scene. The only problem that you might encounter when using this metering mode is when you have very light or dark backgrounds in your portrait shots.

In these instances, the meter might be fooled into using the wrong exposure information because it will be trying to lighten or darken the entire scene based on the prominence of dark or light areas (Figure 6.7). You can deal with this in one of two ways. You can use the Exposure Compensation feature, which we cover in Chapter 7, to dial in adjustments for over- and underexposure. Or you can change the metering mode to Center-weighted. Center-weighted mode uses only the center area of the viewfinder (about nine percent) to get its exposure information. This is the best way to achieve proper exposure for most portraits; metering off skin tones, averaged with hair and clothing, will often give a more accurate exposure (Figure 6.8). This metering mode is also great to use when the subject is strongly backlit.

ISO 400 • 1/60 sec. • f/3.5 • 24mm lens

Figure 6.7 The extremely bright light coming in the window fooled the meter into choosing an underexposed setting for this already contrasty photo.

ISO 400 • 1/30 sec. • f/3.5 • 24mm lens

Figure 6.8 When I switched to Center-weighted mode, my camera was able to ignore much of the window light and add a little more time to the exposure.

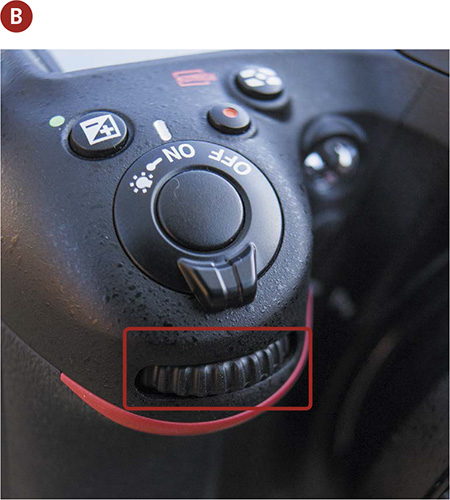

Setting your metering mode to Center-weighted

1. Press and hold the meter button located at the top right side of your camera.

2. While holding the meter button, rotate the main Command dial to locate the Center-weighted Metering icon, and release the meter button once you’ve selected it (A).

3. By default, your camera is set to calculate your center weight with an emphasis on an 8mm center circle. You can reduce or expand that center circle via the Custom Setting menu B4 (B).

Using the AE Lock (Auto Exposure Lock) Feature

Often, your subject won’t be in the center of the frame but you’ll still want to use the Center-weighted Metering mode. So how can you get an accurate reading if the subject isn’t in the center? Try using the Autoexposure Lock feature to hold the exposure setting while you recompose.

AE Lock lets you use the exposure setting from any portion of the scene that you think is appropriate, and then lock that setting in regardless of how the scene looks when you recompose. An example of this would be when you’re shooting a photograph of someone and a large amount of blue sky appears in the picture. Normally, the meter might be fooled by all that bright sky and try to reduce the exposure. Using AE Lock, you can establish the correct metering by zooming in on the subject (or even pointing the camera toward the ground), taking the meter reading and locking it in with AE Lock feature, and then recomposing and taking your photo with the locked-in exposure.

Shooting with the AE Lock feature

1. Find the AE-L/AF-L button (which we’ll call AE-L for short) on the back of the camera and place your thumb on it.

2. While looking through the viewfinder, place the focus point on your subject, press the shutter release button halfway to get a meter reading, and focus the camera.

3. Press and hold the AE-L button to lock in the meter reading. You should see the AE-L indicator in the viewfinder.

4. While pressing the AE-L button, recompose your shot and take the photo.

5. To take more than one photo without having to take another meter reading, just hold down the AE-L button until you are done using the meter setting.

Remember that if you’re using autofocus, the focus and the meter reading will be locked simultaneously.

Focusing: The Eyes Have It

It has been said that the eyes are the windows to the soul, and nothing could be truer when you are photographing someone (Figure 6.9). You could have the perfect composition and exposure, but if the eyes aren’t sharp the entire image suffers. While there are many focusing modes to choose from on your D7200 for portrait work, you can’t beat AF-S (Single-servo AF) mode while using a single focusing point. AF-S focusing will establish a single focus for the lens and then hold it until you take the photograph; the other focusing modes continue focusing until the photograph is taken. The single-point selection lets you place the focusing point right on your subject’s eye and set that spot as the critical focus spot. Using AF-S mode lets you get that focus and recompose all in one motion.

ISO 100 • 1/125 sec. • f/1.8 • 85mm lens

Figure 6.9 When photographing people, you should almost always place the emphasis on the eyes.

Setting your focus to a single point

1. Press and hold the Focus Mode selector, near the lens on the front of the camera (A).

2. While holding the button, rotate the Sub-command dial (B) with your index finger.

3. Select Single Point (S) on the control panel, and release the Focus Mode selector button.

Setting up for AF-S focus mode

1. Press and hold the Focus Mode selector, near the lens on the front of the camera.

2. While holding the button, rotate the main Command dial with your thumb.

3. Release the Focus Mode selector when AF-S is displayed in the control panel.

4. When you are back in shooting mode, use the Multi-selector to move the focus point to one of the 51 available positions. The AF points are visible while looking through the viewfinder.

Now, to shoot using this focus point, place that point on one of your subject’s eyes, and press the shutter button halfway until you hear or see the focus indicator chirp. While still holding the shutter button down halfway, recompose if necessary and take your shot.

I typically use the center point for focus selection. I find it easier to place that point directly on the location where my critical focus should be established and then recompose the shot. Even though the single point can be selected from any of the focus points, it typically takes longer to figure out where other points should be in relation to my subject. By using the center point, I can quickly establish focus and get on with my shooting.

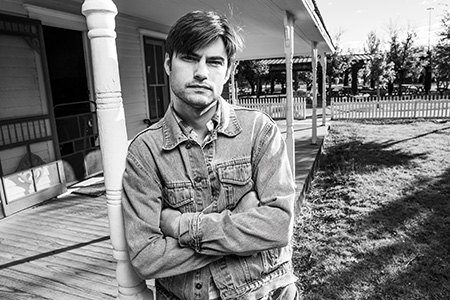

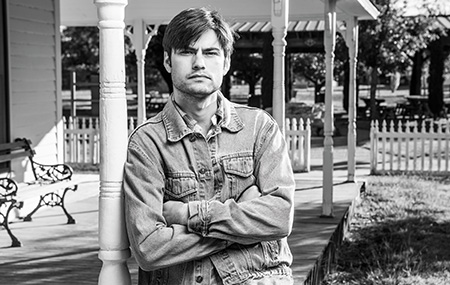

Classic Black-and-White Portraits

There is something timeless about a black-and-white portrait. It eliminates the distraction of color and puts all the emphasis on the subject. To visualize in black and white without having to resort to any image-processing software, set your picture control to Monochrome (Figure 6.10).

ISO 400 • 1/220 sec. • f/2 • 35mm lens

Figure 6.10 Getting high-quality black-and-white portraits is as simple as setting the picture control to Monochrome.

The picture controls are automatically applied when shooting with the JPEG file format; this means the black-and-white image will be created in camera. If you are shooting in RAW, the picture that displays on your rear LCD is a low-resolution JPEG file that mimics what the RAW file will look like once converted in software. Keep in mind, the RAW file that you import from your camera will always contain the color information recorded at time of capture. The RAW file will need to be converted into a black-and-white image using an application such as Adobe Lightroom or Adobe Photoshop. The advantage to shooting in RAW is that you’re able to produce a color image from the original RAW file when desired, plus you now have the ability to produce a black-and-white image. Additionally, you maintain the ability to use color channels to make further adjustments to the black-and-white image. I could go on and on because I love black and white, but to learn more about the process, consider picking up a copy of John Batdorff’s Black and White: From Snapshots to Great Shots.

When shooting RAW, the real value to using the Monochrome picture control is to help you visualize what your image will look like once it’s converted to black and white. Another advantage to using the camera’s built-in Monochrome setting is the ability to create filter effects, even if you don’t have a lens-mounted filter. A red filter will typically lighten skin tones, a yellow filter will darken skies, an orange filter will create contrast in many landscape images, and a green filter will darken reds and lighten greens such as grass.

The Portrait Picture Control for Better Skin Tones

As long as we are talking about picture controls for portraits, there is another control on your D7200 that has been tuned specifically for this type of shooting. Oddly enough, it’s called Portrait. To set this control on your camera, simply follow the same directions as earlier, except this time, select the Portrait control (PT) instead of Monochrome. There are individual options for the Portrait control that, like the Monochrome control, include sharpness and contrast. You can also change the saturation (how intense the colors will be) and hue, which lets you change the skin tones from more reddish to more yellowish.

My recommendation is that you do most of your adjustments to contrast, saturation, and hue in post-processing. Once again, this is not an issue for RAW file shooters, because a RAW file is the digital equivalent of a negative and can be manipulated over and over without any harmful effects. However, if you are a JPEG shooter, tinkering is risky because the in-camera settings are permanently applied to the image. That doesn’t mean that you can’t convert a JPEG file to black and white or reduce sharpening during the post-processing state. You can, but not with the same level of quality that you get with a RAW file.

Detect Faces with Live View

Facial detection is becoming commonplace in digital cameras. Your D7200 has four autofocus modes for Live View: Wide Area AF, Normal Area AF, Subject Tracking AF, and Face Priority AF. These modes are different from the standard modes like AF-S, AF-C, and AF-A. Face Priority mode is probably the slowest of the Live View focusing modes, so use it with a tripod or when your subjects are going to remain fairly still. When you turn on Live View with Face Priority focusing, the camera does an amazing thing: It zeroes in on any face appearing on the LCD and places a box around it. I’m not sure how it works; it just does.

Setting up and shooting with Live View and Face Priority focusing

1. Activate Live View by pressing the LV button. Next, Press the AF mode button and rotate the Sub-command dial to the desired AF-area mode.

2. Point your camera at a person and watch as the yellow frame appears over the face in the LCD.

3. Depress and hold the shutter release button halfway to focus on the face and wait until you hear the confirmation chirp.

4. Press the shutter button fully to take the photograph.

Use Fill Flash for Reducing Shadows

A common problem when taking pictures of people outside, especially during the midday hours, is that the overhead sun can create dark shadows under the eyes and chin. You could have your subject turn his or her face to the sun, but that is usually considered cruel and unusual punishment. So how can you have your subject’s back to the sun and still get a decent exposure of the face? Try turning on your flash to fill in the shadows (Figure 6.11).

ISO 800 • 1/60 sec. • f/1.8 • 24mm lens

Figure 6.11 I used fill flash here to fill in the shadows covering my daughter’s face as she curiously explored a fake bear rug in the dark corner of a large room. I turned the camera vertically so that the light from the flash lit one side of her more than the other, creating a nice transition from light to shadow across her face and body.

This also works well when you are photographing someone wearing a cap. The bill of the hat tends to create heavy shadows over the eyes, and the fill flash will lighten up those areas while providing a really nice catchlight in the eyes.

The key to using the flash as a fill is to not use it on full power. If you do, the camera will try to balance the flash with the daylight, and you will get a flat and feature-less face.

Setting up and shooting with fill flash

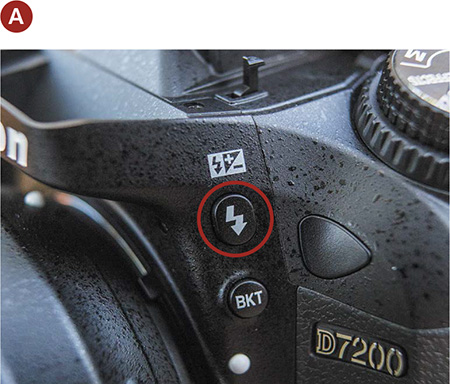

1. Press the pop-up flash button to raise your pop-up flash into the ready position (A).

2. Press and hold the flash button while rotating the Sub-command dial until it reads –0.3 on the control panel and the monitor (B).

3. Release the flash button.

4. Take a photograph and check your playback LCD to see if it looks good. If not, try reducing power in one-third stop increments.

One problem that can quickly surface when using the on-camera flash is red-eye. Not to worry, though—we will talk about how to remedy that in Chapter 8.

Portraits on the Move

Not all portraits are shot with the subject sitting in a chair, posed and ready for the picture. Sometimes you might want to get an action shot that says something about the person, similar to an environmental portrait. Children, especially, just like to move. Why fight it? Set up an action portrait instead.

For the photo in Figure 6.12, I used the Portrait picture control and set my camera to Shutter Priority mode. I knew that there would be a good deal of movement involved, and I wanted to make sure that I had a fairly high shutter speed to freeze the action, so I set it to 1/1000 of a second. I set the focus mode to AF-C and the drive mode to Continuous and just let it rip. There were quite a few throwaway shots, but I was able to capture one that conveyed the energy and action of the subject.

ISO 400 • 1/1000 sec. • f/2.8 • 200mm lens

Figure 6.12 A high ISO and a large, open aperture allowed me to use a fast shutter speed to stop the action.

Tips for Shooting Better Portraits

Before we get to the assignments for this chapter, I thought it might be a good idea to leave you with a few extra pointers on shooting portraits that don’t necessarily have anything specific to do with your camera. Entire books cover things like portrait lighting, posing, and so on. But here are a few simple tips that will make your people pics look a lot better.

In general, avoid the center of the frame

This falls under the category of composition. Instead of plunking your subject smack-dab in the middle for what I like to call the “mug shot” pose (Figure 6.13), position them toward the side of the frame (Figure 6.14)—it just looks more interesting.

ISO 400 • 1/30 sec. • f/4 • 17mm lens

Figure 6.13 When shooting wide-angle environmental portraits, I sometimes unknowingly place the subject in the center of the frame, which doesn’t allow the eye to move toward or away from the subject.

ISO 400 • 1/30 sec. • f/4 • 17mm lens

Figure 6.14 Create a more interesting portrait by placing your subject off to the side. Notice how the eye is drawn more strongly to the subject by the heavier weighting of the lines (seats) in the foreground.

On occasion, though, centering your subject works to your advantage in creating a mood. My best advice is to change it up and see which portrait conveys the message you’re looking for, because there’s no hard-and-fast rule, just options!

Choose the right lens

Choosing the correct lens can make a huge impact on your portraits. A wide-angle lens can distort the features of your subject, which can lead to a portrait with a distorted perspective (Figure 6.15). I typically use a wide-angle lens only when I’m trying to capture more of the environment or when I’m photographing larger groups. Select a longer focal length for up-close and personal shots of the face. This helps fill the frame and reduce distortion (Figure 6.16).

ISO 100 • 1/125 sec. • f/8 • 24mm lens

Figure 6.15 A wide-angle focal length at this camera-to-subject distance pushes songwriter Kenneth O’Meara toward the camera.

ISO 100 • 1/125 sec. • f/8 • 70mm lens

Figure 6.16 I used a longer focal length to maintain a more appropriate perspective and to keep Kenneth’s form (his face, especially) from distorting.

Use the frame

Have you ever noticed that most people are taller than they are wide? Turn your camera vertically for a more pleasing composition (Figure 6.17).

ISO 100 • 1/4000 sec. • f/2.8 • 24mm lens

Figure 6.17 Get in the habit of turning your camera to a vertical position when shooting portraits. This is also referred to as portrait orientation.

Sunblock for portraits

The midday sun can be harsh and can do unflattering things to people’s faces (Figure 6.18). If you can, find a shady spot out of the direct sunlight. You will get softer shadows, smoother skin tones, and better detail. This holds true for overcast skies as well. Alternatively, you can place a transparent diffusion screen (commonly found as part of many reflector kits) between the harsh sun and the subject to soften the light (Figure 6.19). Just be sure to adjust your white balance accordingly.

ISO 100 • 1/2000 sec. • f/1.8 • 85mm lens

Figure 6.18 Harsh shadows from direct sunlight in the middle of the day are typically considered unflattering, especially the shadows cast across the eye sockets by eyebrows.

ISO 100 • 1/1600 sec. • f/1.8 • 85mm lens

Figure 6.19 I diffused the sun using a transparent diffusion screen. The screen allows light through, but the direct rays are scattered more, reducing the depth of the shadows.

Give them a healthy glow

Nearly everyone looks better with a warm, healthy glow. Some of the best light of the day happens just a little before sundown, so shoot at that time if you can (Figure 6.20).

ISO 100 • 1/400 sec. • f/2.8 • 200mm lens

Figure 6.20 You just can’t beat the glow of the late afternoon sun for adding warmth to your portraits—or to their background.

Keep an eye on your background

Sometimes it’s so easy to get caught up in taking a great shot that you forget about the smaller details. Try to keep an eye on what is going on behind your subjects so they don’t end up with things popping out of their heads (Figures 6.21 and 6.22).

ISO 640 • 1/60 sec. • f/2.8 • 35mm lens

Figure 6.21 When photographing some wide shots of champion diver Jennifer Mangum, I noticed the yellow air duct emerging from behind her head. It is important to slow down and notice these details.

ISO 640 • 1/60 sec. • f/2.8 • 35mm lens

Figure 6.22 Shifting my perspective a bit solved the distracting issue without sacrificing the storytelling environment.

Frame the scene

Using elements in the scene to create a frame around your subject is a great way to draw the viewer in. You don’t have to use a window frame to do this. Just look for elements in the foreground that could be employed to force the viewer’s eye toward your subject (Figure 6.23).

ISO 1250 • 1/60 sec. • f/7.1 • 23mm lens

Figure 6.23 The window to the small shop in which this New Zealand locksmith worked was the perfect frame for his street portrait.

More than just a pretty face

Most people think of a portrait as a photo of someone’s face. Don’t ignore other aspects of your subject that reflect his or her personality—hands, especially, can go a long way toward describing someone (Figure 6.24).

ISO 800 • 1/60 sec. • f/4 • 24mm lens

Figure 6.24 I enjoy photographing the hands of artists. My friend James has always served as a great portrait subject.

Get down on their level

If you want better pictures of children, don’t shoot from an adult’s eye level. Getting the camera down to the child’s level will make your images look more personal (Figure 6.25).

ISO 100 • 1/100 sec. • f/8 • 70mm lens

Figure 6.25 A child’s first birthday is a big occasion, and so is the cake! I wanted to get on this one-year-old’s level since it was his day!

Eliminate space between your subjects

One of the problems you can encounter when taking portraits of more than one person is that of personal space. What feels like a close distance to the subjects can look impersonal to the viewer. Have your subjects move very close together, eliminating any open space between them (Figure 6.26).

ISO 100 • 1/100 sec. • f/8 • 70mm lens

Figure 6.26 Getting your subjects close together tells a better story. This group of my photography students grew close over a study-abroad trip to New Zealand. Moving them closer together with Milford Sound in the background was a strong way to visualize their friendship.

Chapter 6 Assignments

Depth of field in portraits

Let’s start with something simple. Grab someone you like and start experimenting with using different aperture settings. Shoot wide open (the widest your lens goes, such as f/2.8 or f/4) and then really stopped down (like f/22). Look at the difference in the depth of field and how it plays an important role in placing the attention on your subject. (Make sure you don’t have your subject standing against the background. Get some distance so that there is a good blurring effect of the background at the wide f-stop setting.)

Discovering the qualities of natural light

Pick a nice sunny day and try shooting some portraits in the midday sun. If your subject is willing, have them turn so the sun is in their face. If they are still speaking to you after you have blinded them, have them turn their back to the sun. Try this with and without the fill flash so you can see the difference. Finally, move them into a completely shaded spot and take a few more.

Picking the right metering method

Find a very dark or light background and place your subject in front of it. Now take a couple of shots, allowing a lot of space around your subject for the background to show. Now switch metering modes and use the AE Lock feature to get a more accurate reading of your subject. Notice the differences in exposure between the metering methods.

Street portraits

Approach a stranger and practice your street photography. Find a busy, public place and ask someone if you can take their picture. If they decline, find someone else. Remember to smile and act comfortable. Offer your business card or email address so they can email you to get the portrait. Then, practice taking some shots that use environmental data to tell a story.

If this is the first time you’ve done this, it’s natural to be nervous. Just remember that it becomes easier with practice.

Share your results with the book’s Flickr group!

Join the group here: flickr.com/groups/nikond7200_fromsnapshotstogreatshots