When éditions Eyrolles, my French publisher, asked me to write a book on panoramic photography, I accepted right away. At the time, I wasn’t sure of how much work it would entail, but I was sure about one thing: was going to speak about a subject that had fascinated me for more than 20 years. Actually, it was during my first trip to Rome at the age of 14 – equipped with the family camera, a Kodak 126 Instamatic – that I first perceived to what extent I “saw” panoramically, since I could not stop myself from wanting to crop my photos this way! It is impossible for me to say why; I simply believe that this is the natural format for me. I love to recreate the emotion that a place instills in me while viewing it.

Preparation of the Fireworks and Decoration for the Feast Given in Piazza Navona, Rome, on November 30, 1729, for the Birth of the Dauphin, on the Occasion of the Birth of the Heir Apparent, by the painter Giovanni Paolo, Louvre Museum. The painter has chosen a panoramic format to show all of the famous Roman square in turmoil.

The story behind a book starts long before a publisher’s contact, particularly with regard to certain experiences that are more important than others. Without a doubt, the first of these for me was reading the book, Marcel Proust, la figure des pays, by François-Xavier Bouchart, at the Nanterre public library when I was an adolescent. I had the strong sensation that a door had just opened wide for me. This was because a great photographer had published a book containing only panoramic photographs – and more importantly, ones that were so close to my own sensibilities – thus, permitting me to express myself more in this format than in any other.

My second important photographic encounter concerned the work of Ansel Adams. His black-and-white photographs of American landscapes and architecture, taken with a large-format camera, were unlike anything I had ever seen before (indeed, I continue to admire them). At the time, I knew that I wanted to wed the vision of panoramic photography to the richness and detail of large format. But it was only much later that I heard about a new, swing-lens panoramic camera, the Noblex 150, first produced in 1992, which is the one I used until 2004.

Two technical photo books had an effect on me as well: La Photo, by Chenz and Jean-Loup Sieff (because a sense of humor was always implicit), and La Prise de vue et le développement, by Thibaut Saint-James (for its remarkable text and the richness of the ideas expressed there). It was with the latter book that I patiently learned the Zone System, and perhaps even more, to control light. This is why continue to think that the Zone System is an important school of thought, even at a moment when automatic light meters are achieving real miracles. Why do I say this? Because without the Zone System I never would have had the idea and the requisite technique to achieve my nighttime photographs and color photographs of twilight. However, far from being a die-hard supporter of the Zone System, have just taken what was useful, and modified it to suit my working method. I like this combination of tradition and modernity.

Ever since I bought my first Noblex six years ago, I have not stopped hearing that panoramic photography is à la mode. But why should this type of photography be in fashion, and therefore, destined to disappear, when art history, notably painting, shows us that artists, albeit a minority, have never stopped expressing themselves in this format? Panoramic photography depends on a type of camera that, even in the not-so-distant past, was often cumbersome and costly. However, the recent arrival of lighter panoramic cameras, compatible with journalistic photography, and the maturity of the promising joining method have begun to change this preconception

It was during a visit to the Louvre that I first entertained this idea. While visiting the different rooms and artistic periods, I noticed that this elongated format was always present there as well. This does not seem so astonishing when one realizes that many panoramic artists have shared the opinion that this style of vision worked best because it was the most natural. How could it have been different when the Italian painter Lorenzo di Credi (ca. 1460–1537) painted the Annunciation in the fifteenth century?

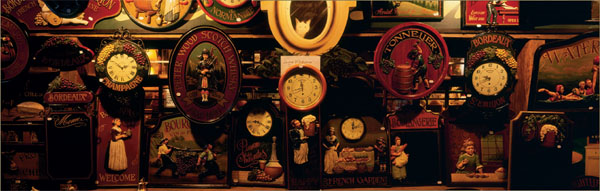

Personally, I love this format, this privileged means of providing a sense of the entire harmony and ambiance of a place rather than just an isolated detail. This is equally the case in a painting from the eighteenth century by Giovanni Paolo (1691–1765), representing preparations for a Roman fireworks display in 1729. Nevertheless, it was not until 1799 that the word panorama first appeared, coined by Robert Barker (1739–1806).

So it is hardly surprising that the first panoramic cameras should arrive shortly after the beginning of photography in 1839. As early as 1843, Joseph Puchberger of Retz, Austria, was making his first panoramas on curved plates measuring 24 inches, with the aid of a swing-lens that had a focal length of around 200 mm. The angle of view was 150 degrees, the same as a Noblex or a Widelux built 170 years later. And in the musée Carnavelet (museum of the history of Paris), one also finds a panoramic daguerreotype view of Paris, View of the Pont-Neuf, the quays of the Louvre and the Mégisserie, dating to around 1845–1850.

This laterally reversed photograph, titled View of the Pont-Neuf, the Quays of the Louvre and the Mégisserie, is attributed to Lerebours, ca. 1845–1850, Carnavalet Museum. François-Xavier Bouchart rephotographed this same scene 180 years later with the same kind of rotational camera.

Following this, a number of brilliant photographers continued to improve their cameras, taking them almost everywhere, in spite of their large size. And in 1859, the first patent was filed for a camera with a curved back; others were already using the joining method by juxtaposing mosaics of images placed one alongside the other. 1904 marks the next important date in the history of panoramic photography, because the famous Cirkut cameras using a 25 cm × 40 cm film format appeared in that year. A number of collectors own these today.

To conclude, I would like to mention two other important names in the history of panoramic photography. In the 1920s, the French photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue (1894–1986) photographed scenes of daily life with 6 cm × 12 cm glass plates that were a far cry from the contemplative tradition of certain American photographers and the French 35 mm journalistic tradition. Thirty years later, Joseph Sudek photographed the city of Prague with a swing-lens camera; some of these photographs were featured in a very beautiful book, Prague en panoramique, which unfortunately is unavailable today. This work was made in the 1950s and published for the first time in 1959, 20 years before the first modern 6 × 17 panoramic cameras.

The goal of this book is to explore different aspects of panoramic photography as practiced today, from the most traditional to the most contemporary. I will have attained my goal if I can prove that it has never been easier to make panoramas, both in terms of the light weight of the equipment and, above all, in quality. Digital photography has also brought down many barriers and opens new vistas concerning this unique way to see the world and express oneself.

In Chapter One, we will take stock of the different ways that are available to obtain images having at least a 2:1 ratio – the minimum required for a panoramic format. Then, in the second chapter, we will look at how a panoramic photograph may be affected by the type of camera being used and how this in turn influences the final composition. In the third and fourth chapters, we will make an inventory of flatback panoramic cameras, followed by rotating ones. Chapters Five and Six are devoted to the so-called joining method. This new way of making panoramic photographs can be learned without prior experience, since the results obtained are very interesting and the creative potential is unlimited. The last chapter of the book is devoted to the presentation and archival storage of panoramic photographs, and all that concerns them at this moment when digital photography is aiding a format that is finally moving away from being marginalized. An appendix of resources brings this book to a conclusion.

One final word: This book has been written with certain preconceptions in mind. To start, I have not wanted to overload the pages with comparative tables that just about any Internet site or similarly documented source could provide in greater detail (e.g., see my site, www.arnaudfrichphoto.com, which I have done my best to make a complement to this book). The source of supply and bibliographic sections at the back of the book will also aid you in your search for supplementary information. Instead, I have preferred to leave room for photographers whose reputation often exceeds their native land – something that is not completely out of place in a technical book. And by stressing their respective advantages and disadvantages, I have hoped to show the characteristics of different panoramic cameras, as well as their amazing abilities. Here, I have preferred to explain the possibilities of a camera rather than emphasize what one should not try to do with them; if I had done the latter, another photographic author would soon prove me wrong.

In closing, I believe that I truly will have attained my goal when you want to leaf through this book after panoramic photography has become very familiar to you, even to the point where it is your full-fledged manner of expression – as is the case for more and more photographers in the world today.

Photo by Josef Sudek.

Caption (on following page): Photo by David J. Osborn.

Photo by Hervé Sentucq.

Photo by Aurore de la Morinerie.

Photo by Franck Charel.

Photo by Arnaud Frich.

Photo by Macduff Everton.