17

Production Strategies

There is a need for discipline, structure, and coverage in almost any kind of production. Decisions need to be made about the goal of the project, form and content, point of view, methodology, and aesthetics. Depending on the kind of production, physical preparation involves research, scripts, outlines, shot lists, storyboards, meetings, location scouting, test footage, permissions, clearances, call sheets, schedules, or rehearsals. Entire books can be written on any one of these aspects of preproduction. This chapter discusses a few selected strategies and relevant production aids for palm-sized production of non-fiction, fiction, student exercises, and experimental media. Let’s start with thematic production outlines built into the camcorder itself.

Story Creator

The G10/XA10 comes with a built-in Story Creator tool that provides shot recommendations and outline structures for certain types of productions and themes. It also offers a way to tag shots to points in the Story Creator outline for later grouping for review or playback. Because this feature is primarily for amateurs, Story Creator is one of the few menu items available in full AUTO mode in addition to the M and CINEMA modes.

The first three Story Creator themes relate entirely to home video:

![]() Travel

Travel

![]() Kids & Pets

Kids & Pets

![]() Party

Party

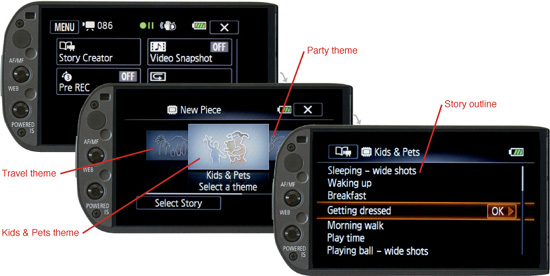

When you select a theme, the touchscreen outlines categories of shots relevant to that theme and presents them in a coherent order. (See Figure 17.1.) Under Travel, for example, the outline starts with introducing the travelers, planning the trip, shopping for the trip, packing, expectations, taking off, and so on. The middle contains entries for eating, landmarks, visits, adventure, funny situations, and making friends. The end has categories for a sunset (or if you take this metaphorically, a concluding shot), memories, thinking about the next trip, and additional scenes. In a similar fashion, the Kids & Pets theme, suggests shots like waking up, breakfast, getting dressed, morning walk and playtime (see Figure 17.1). Story Creator helps completely inexperienced media makers think more fully about the kinds of shots they could be taking for home movies on travel, kids, pets, and parties.

Figure 17.1 Story Creator. To tag a clip that you intend to shoot, press OK next to the outline entry.

The last three themes on the list are also basic:

![]() Ceremony. Ceremony is designed for the amateur, but it could help someone starting out in event videography. It is the most developed outline and is obviously based on a wedding, but could be adapted to other events. The outline suggests interviews with the main character(s) and covering pre-event details like planning, invitations, dress, and rehearsal. It moves on to recording thoughts from the main character(s) or someone else just before the event, backstage activity, and the ceremony itself. The outline includes guest interviews, the dinner, toasts, speeches, and concluding items like last comments, the exit of the main character(s), guests leaving, and a place to tag additional scenes.

Ceremony. Ceremony is designed for the amateur, but it could help someone starting out in event videography. It is the most developed outline and is obviously based on a wedding, but could be adapted to other events. The outline suggests interviews with the main character(s) and covering pre-event details like planning, invitations, dress, and rehearsal. It moves on to recording thoughts from the main character(s) or someone else just before the event, backstage activity, and the ceremony itself. The outline includes guest interviews, the dinner, toasts, speeches, and concluding items like last comments, the exit of the main character(s), guests leaving, and a place to tag additional scenes.

![]() Blog. The Blog theme prompts you to identify main characters, identify what is at stake, and do interviews, but is much less detailed than the other themes in providing a model or in recommending a structure (except to suggest obtaining establishing shots and getting both wide views and close-ups).

Blog. The Blog theme prompts you to identify main characters, identify what is at stake, and do interviews, but is much less detailed than the other themes in providing a model or in recommending a structure (except to suggest obtaining establishing shots and getting both wide views and close-ups).

![]() Unrestricted. The Unrestricted theme simply offers a way to tag shots. No internal structure is provided. It would have been much more useful if the Unrestricted theme had numbered or lettered sub-choices to sort shots more individually. A set of blank A, B, C, D, and E options could have been tags for five separate unrestricted projects, or selective parts within a single unrestricted category. Or this section could have had generic categories like Interviews, Dialogue, Action, Establishing Shots, Extra Scenes, and B-Roll. But unfortunately, the only capability of Unrestricted is to tag shots into a whole undifferentiated category. The easier way to put shots for a single project into one location is to dedicate a separate memory chip to a particular project. The only meaningful use of Story Creator in Unrestricted mode is to differentiate shots from other material on the same memory chip, possibly when shooting a long-term project off and on among other projects, or to identify B-roll from everything else. But then these other clips would have to be one of the other five themes or else go unidentified.

Unrestricted. The Unrestricted theme simply offers a way to tag shots. No internal structure is provided. It would have been much more useful if the Unrestricted theme had numbered or lettered sub-choices to sort shots more individually. A set of blank A, B, C, D, and E options could have been tags for five separate unrestricted projects, or selective parts within a single unrestricted category. Or this section could have had generic categories like Interviews, Dialogue, Action, Establishing Shots, Extra Scenes, and B-Roll. But unfortunately, the only capability of Unrestricted is to tag shots into a whole undifferentiated category. The easier way to put shots for a single project into one location is to dedicate a separate memory chip to a particular project. The only meaningful use of Story Creator in Unrestricted mode is to differentiate shots from other material on the same memory chip, possibly when shooting a long-term project off and on among other projects, or to identify B-roll from everything else. But then these other clips would have to be one of the other five themes or else go unidentified.

To use Story Creator, choose FUNC and scroll down to Story Creator. Then select a theme and tap the appropriate entry on its outline before taking shots that belong in that category. If you select the Travel theme and a sub-category such as Landmarks, a storybook icon appears on the upper part of the touchscreen and the word Landmarks appears across the bottom of the screen as indicators that the camcorder is in Story Creator mode and is tagging shots for this category.

Remember to close Story Creator when you are no longer shooting that particular item on the outline. To do so, choose FUNC > Story Creator and select Yes to end Story Creator mode. When you close and reopen Story Creator, which could be a few seconds later or even months later, the outline will list how many clips were taken in each category. This feature is useful for instantly knowing you have seven shots of landmarks but no shots of eating, scenery, or new friends. To move onto another item in the outline, you must close Story Creator and re-open it. To make this practical in ongoing situations, you can set one of the re-assignable buttons to toggle Story Creator on and off. This saves having to press FUNC and scrolling down to Story Creator. To do so, choose FUNC > MENU > Tool icon > Assign Button 1 or 2 > Story Creator.

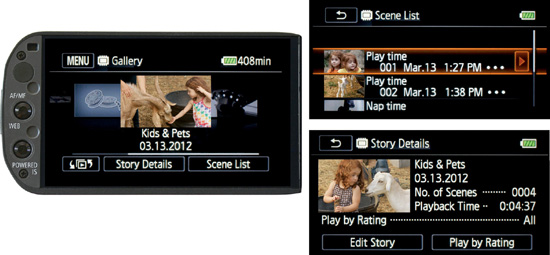

Where Story Creator can have some professional use is in reviewing your footage. To do so, toggle the Camera/Playback button to Playback, touch the Index icon (lower left), select Gallery, and horizontally scroll to and select one of the six story theme icons. To play the entire outline of clips within a story, tap the theme icon. When a clip plays, the on-screen controls for pause, stop, fast forward, and reverse are similar to controls for regular playback. Instead of directly playing the clips, tapping Story Details (at the bottom center of the Gallery screen) displays information about date, number of clips already shot, total playback time, and provides the ability to play clips by rating. This becomes a way to review culled selections of shots while in the field to see if you have covered everything acceptably.

Tapping Scene List (instead of Story Details) opens a vertical list that displays the icon of each clip, its play time, date, and rating. (See Figure 17.2.) There are also some editing options, including the ability to rate scenes. To access these, scroll to a clip in the Scene List and press the orange arrow to the right of the entry. The Edit Scene window opens; touch the desired rating (zero to four stars) or an editing function (delete, copy, or move the clip within or between stories).

Figure 17.2 Scene List and Story Details allow you to review the clips you have taken for a particular story theme. The orange arrow to the right of the selected entry in the Scene List leads to a screen for rating and editing.

A story’s default thumbnail image is the first frame of the first clip in the outline. To change this image, start at the main Gallery screen, choose Story Details > Edit Story > Story Thumbnail, and select the desired thumbnail. A story’s default title is its date. To change this to a title of up to 14 characters, start at the main Gallery screen, choose Story Details > Edit Story > Edit Title, and use the virtual keyboard that appears on the screen to type a title. To enter your changes and exit any of these editing functions, tap OK, and then tap the return arrow twice.

Non-Fiction

Non-fiction can include news, event videography, narrated visual essays (typically seen as television documentaries), interviews, historical documentaries with archive footage, ethnographic documentaries, activist media for social change, personal diaries, cinéma vérité, and the observational style of direct cinema, to mention a few examples. A production strategy for one kind of non-fiction production would be considerably different from another.

A difference between documentary and TV news is that documentary is usually a more developed form, treating its subject in greater depth than a typical one- to three-minute news clip, and is more interested in the human condition than in the latest development of a current event that specifically categorizes something as news.

News

News gets documented not simply because a camera happens to be present—although this happens more frequently as a vast number of people carry video-capable cell phones and other devices. Professional news gets videoed because the news organization casts a net of assignments to look for news in expected places and reporters cover individual beats like city hall, the courthouse, police, emergency, fire, and anticipated special events. If a station casts a different kind of net, it gets a different story or a different slant on the news. Unfortunately, most commercial news stations present nearly identical news, often with the same lead story. News stories and commercials interweave seamlessly with each other in a pre-planned balance of airtime— until something truly out of the ordinary happens, such as the assassination of President Kennedy, the resignation of Richard Nixon, the Challenger disaster, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina.

Somewhere in between the catastrophic event and the routine news net (which generates routine news) is space for a more varied approach to the news for a news organization, public television, public access cable, and particularly for those who post on the Internet. Increasingly, it is the viral news story on the Internet that scoops the multi–billion dollar networks. This happens with one-shot postings and with individual blogs that provide ongoing news or commentary.

Camcorders with run-and-gun capabilities like the G10/XA10 have a role in this kind of news gathering, but the G10/XA10 could also pass muster on a commercial news show. Being at the right place and the right time with a well-positioned camcorder is often more possible with a highly versatile 1.7-pound camcorder than a 25-pound rig.

In 1972, a collective called Top Value Television (TVTV) covered the Republican National Convention with 5-pound cameras tied to 20-pound porta-pak video-recording units strapped on their backs. They provided a completely different slant on the convention by showing rehearsals for so-called spontaneous events and extensively examined the mainstream press, which covered the highly scripted convention yet never looked below the surface.

Direct Cinema

I want to go into one approach to documentary in detail, Direct Cinema, because the G10/XA10 lends itself perfectly to its observational style. Direct Cinema filmmakers include Ricky Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker, Robert Drew, Fred Wiseman, and the Maysles brothers. Landmark films include Crisis: Behind a Presidential Commitment, Quint City U.S.A., Don’t Look Back, Salesman, Grey Gardens, Titicut Follies, High School, Seventeen, and The War Room.

Direct Cinema is an observational slice of life that tells its own story without needing narration or explanation. It is accomplished by shooting a real-life event with an unobtrusive handheld camera in available light within an event’s circle of action and paying attention to human interactions, personal values, ideology, and natural drama. For the footage to tell its own story, the filmmaker looks for conflict or at least contrasts and opposing forces within the naturally occurring event. Even within everyday events, the filmmaker tries to find Aristotelian elements of plot structure: exposition, initiating action, complication, foreshadowing, crisis (moment of decision), anagnorisis (moment of truth, discovery, recognition, realization, or revelation), peripeteia (turning point, reversal, gain or loss, or moment that cannot be easily undone), climax (the height of verbal or visual conflict), and denouement (unraveling or settling).

Direct Cinema as a documentary genre is interested in the human experience: social actors in situations that would occur even if the camera were not there. Characters are tested through conflict—in particular when pressed to make decisions in a moment of crisis. Characters are conveyed through their moments of discovery and revelation, the decisions they are pressed to make, and their moments of change— particularly those that result in a gain or loss. The Direct Cinema filmmaker looks for such moments.

Let’s contrast this with an event videographer. Shooting a wedding, an event video-grapher will want to get each element of the ceremony as well as ample footage of the bride, groom, and their closest friends and relatives having a good time. The video will be celebratory and will contain idealized memories of the high points of the occasion, similar to the outline provided in Story Creator. Conversely, a Direct Cinema documentary maker would look for natural drama, conflict, tension, stress, things that went wrong, last-minute decisions, character-revealing moments, the human story behind the ceremony—a completely different documentation of the same event.

Direct Cinema observational video is characterized by the following:

![]() A central interest in human character (words and actions that reveal inner values)

A central interest in human character (words and actions that reveal inner values)

![]() A story or event that tells itself

A story or event that tells itself

When shooting in the Direct Cinema style, you’ll want to keep these points in mind:

![]() Gain access to private space and privileged intimacy. (For this, you have to gain trust.)

Gain access to private space and privileged intimacy. (For this, you have to gain trust.)

![]() Do not stage the subjects or ask them to repeat anything.

Do not stage the subjects or ask them to repeat anything.

![]() Do not interview.

Do not interview.

![]() Look for naturally occurring Aristotelian elements (conflict, crisis, revelation, discovery, character, and plot).

Look for naturally occurring Aristotelian elements (conflict, crisis, revelation, discovery, character, and plot).

![]() Look for relationships—people-to-people, people-to-environment, people-to-objects.

Look for relationships—people-to-people, people-to-environment, people-to-objects.

![]() Look for value-laden behavior and psychologically revealing detail (actions, objects, mannerisms, and gestures). Seek “truth in detail.”

Look for value-laden behavior and psychologically revealing detail (actions, objects, mannerisms, and gestures). Seek “truth in detail.”

![]() Look for existential complexity of characters, including their contradictions.

Look for existential complexity of characters, including their contradictions.

![]() Position the camera (and consequently the spectator) intimately within the circle of action.

Position the camera (and consequently the spectator) intimately within the circle of action.

![]() Use the unobtrusive hand-held camera as an active, mobile witness.

Use the unobtrusive hand-held camera as an active, mobile witness.

![]() Shoot in structured long takes. Do not shut the camera off too soon.

Shoot in structured long takes. Do not shut the camera off too soon.

![]() At appropriate moments, physically move to meaningful new positions instead of always zooming or panning (which creates a static position for the spectator).

At appropriate moments, physically move to meaningful new positions instead of always zooming or panning (which creates a static position for the spectator).

![]() Do not overreact with the camera. Resist the tendency to pan to everything. Determine when major adjustments are occurring and pan or move accordingly.

Do not overreact with the camera. Resist the tendency to pan to everything. Determine when major adjustments are occurring and pan or move accordingly.

![]() Some moments of dialogue and action may occur off frame. This is acceptable if represented by sound or on-screen reaction.

Some moments of dialogue and action may occur off frame. This is acceptable if represented by sound or on-screen reaction.

![]() Be selective with the frame. Use close-ups and medium shots to focus attention; over-the-shoulder and line-of-sight shots to share a view; and occasional full shots, group shots, or establishing shots to show overall relationships.

Be selective with the frame. Use close-ups and medium shots to focus attention; over-the-shoulder and line-of-sight shots to share a view; and occasional full shots, group shots, or establishing shots to show overall relationships.

![]() Use a high shooting ratio.

Use a high shooting ratio.

Making a Direct Cinema documentary is something like novelist Norman Mailer’s definition of American existentialism: “the entrance into a situation where you don’t know how it is going to turn out.” Be open to what you actually find instead of shooting only what fills your preconceived notions. Shoot a lot of footage (like 20:1, 40:1, or even 100:1) and organize it into a coherent story in the editing.

In Direct Cinema, the camera is unacknowledged. Some erroneously call this a “fly-on-the-wall” approach, but this metaphor implies a kind of aloof and stand-offish approach (like a bank surveillance camera) and does not capture the element of trust that allows the mobile Direct Cinema camera to intimately and actively move within the center of things as they happen. Rather that an inert housefly, the Direct Cinema camera is more like an unnoticed butterfly or firefly that moves in and around the subjects, who are preoccupied with the event at hand. Various other kinds of documentaries may involve more passive observation outside the circle of action or even more intimate first-person observation, or might involve media makers and participants who acknowledge the filmmaking process in what might be called a reflexive mode. The non-intervention of the Direct Cinema observational media maker is quite different from a Michael Moore provocateur or catalyst, which would lead to a completely different set of assumptions and strategies.

I have described one approach in detail, but all of these approaches to non-fiction are viable, and each deserves a well-considered strategy. You need to think out potential relationships between form, content, the documentary process, and the ultimate goal, which in documentary is to say something meaningful and relevant about the factual world.

Interviews

Research your subject. People are used to giving routine, self-serving answers, and what you end up recording in an interview is often their public mask. If you ask a well-known sculptor, “Why did you become a sculptor?” you will get the response he or she gives everyone. Stock questions get stock answers. If you ask, “Why did you become a sculptor instead of a plastic surgeon?” you might get a moment of introspection and a different kind of answer.

Certain formal decisions need to be made before an interview. Should every interview for the production be set up identically or should each have a noticeably different composition and environment? Should the environment reflect the values and personal space of the subject? Should the interview be a static sit-down session, or while walking, driving in a car, or engaged in an activity? Will the interviewer interact with the subject on any level other than asking questions? Will there be an on-camera, off-camera, or behind-the-camera interviewer? Will the subject address the questioner, the camera operator, or the camera itself? Will questions be asked that require a story to answer or simply a yes or no? Will the camcorder be handheld or on monopod or tripod for the interview? Will the interview be recorded with a lava-liere, boom mic, hand-held mic, or camera-mounted mic (in which case the camcorder needs to be relatively close)?

Fiction

One of the most important approaches to shooting scripted material is marking up the script with notes and arrows for camera setups. For example, a dramatic scene might have 20 shots taken from three different setup positions plus an additional coverage angle as backup. These three setup positions could be called A, B, and C and the coverage angle could be D. The footage expected from these positions might be drawn as vertical lines down the script to indicate the in point and out point of each shot within a setup and where overlaps should occur. The coverage angle may cover major portions or all of the scene. In addition to being identified as A, B, C and D, the lines might be drawn in different colors. You are now better prepared to set up the camera and efficiently take those 20 shots from four positions without missing important angles.

Whether it is marked in the dialogue script or exists separately, a shot list is usually preconceived before shooting. This might simply be a list of shots with references back to dialogue cues or could be written down with complete dialogue and descriptions of action to form a detailed shooting script. This too would be particularly helpful if it is further broken down into setups and organized for ease of shooting.

The shot list can also be visualized in the form of a series of storyboard panels, where the opening frame or a significant moment from each shot is hand drawn, photographed, extrapolated from rehearsal video, or computer generated. Not every production storyboards, but most scenes can benefit from the kind of thinking and previsualization that go into storyboards. There are a number of things you can tell by looking at a storyboard, including whether there is a significant compositional change from shot to shot. (There usually should be—otherwise, why change the shot?) A storyboard represents the overall visual flow or shape of a sequence—for example, an establishing shot, a two shot, several waist-high reverse angles, a shift to head and shoulder close-ups at a significant beat within the scene, a two shot in depth as one character leaves, and a concluding reaction shot of the remaining character.

A call sheet is a daily schedule for cast and crew that lists times and locations and is keyed to script pages and eighths of pages. (Call sheets are traditionally based on eighths of a script page.) Based on a thorough breakdown of the script, the shot list, and an analysis of the shooting schedule, the call sheet lists the elements on call for each scheduled scene: actor, stunt, extras, props and set objects, costumes, vehicles, animals, make-up and hair, special equipment, et cetera. There are standard versions of call sheets and computer programs for making call sheets with color coding and with certain kinds of items circled, boxed, underlined, and asterisked. They can also be posted online.

This is simply a hint at the kind of organization you might want to consider for scripted productions. There are numerous books on production planning.

Experimental

Many experimental works attempt to see the world with fresh eyes by inventing a new form/content relationship or by altering or recontextualizing the subject matter. Defamiliarization is a concept from Russian formalism that pervades 20th and 21st century aesthetics. Theorist Viktor Shklovsky claims defamiliarization is the essence of all art. A palm-sized camcorder offers endless possibilities for experimenting with how we represent the world, and human experience can be presented in media in numerous ways.

As a professor at the Danish National Film School, Jørgen Leth used the formalist concept that creativity is spurred and challenged by setting limitations. Jørgen’s film exercises for his students would set obstructions on each exercise that would pose a difficulty that would need to be creatively solved. In 2003, Danish filmmaker Lars von Trier, who had become an internationally known filmmaker, turned the tables on his mentor at the Danish National Film School and made a feature film about the process called The Five Obstructions. Von Trier had his former professor remake The Perfect Human (a short film that Leth had made 35 years earlier) five different ways, with von Trier imposing a nearly impossible condition on each new version. The challenge was in each case to make the film as effective or more effective than the original while being prohibited from doing anything the same way. Each time, the imposed obstacle would cause Leth to have to rethink the whole process. The first obstruction was that every shot in the film had to be 12 frames long (a half second). The second obstruction involved setting up difficult social conditions in “the worst place in the world” under which the new version is shot. Another version involved reconceiving the film as an animation, a form that neither Leth nor von Trier like. Sometimes, artificially imposing obstacles forces the filmmaker to break out of old habits and discover new creative solutions.

B-Roll

B-roll is secondary or supplemental footage. The concept is useful for news, documentary, event videography, and even works of fiction. Part of the production process involves the discipline of getting the additional shots for cutaways, inserts, establishing shots, and background details that may ultimately be needed in the editing stage. A preparatory B-roll shot list or outline can be useful. Do not limit yourself to only preconceived ideas; you should also be open to finding unique and unexpected details on location at the spur of the moment.

The Video Snapshot function is convenient for taking a series of very short B-roll clips that are 2, 4, or 8 seconds in length. You can turn on this function fairly quickly by pressing FUNC > Video Snapshot, and can exit it just as quickly. I will discuss Video Snapshot in greater detail near the end of this chapter.

Comparable to the importance of B-roll for visuals, audio can be just as significant. Plan to record distinctive ambient sounds, wild sound, wild lines, and potential Foley sounds while on location. Here, too, a list can be useful. As part of your audio B-roll footage, record room tone for each location. Room tone is a 30-second recording of the “silence” of an interior location that captures its unique acoustic presence and its sense of space while no other sounds are being made. “Air” is the term for an equivalent 30 seconds of “silence” at an exterior location. The audience can hear the difference between absolute silence, which is perceived as an empty hole in the sound track, versus room tone, which has the character of an actual acoustical environment when it is quiet. Air and room tone are used in the editing process to fill in pauses, clean up noisy moments, and make sound bridges for audio recorded at each particular location. The steps for recording room tone and air are described in Chapter 7, “Improving Sound.”

Teaching and Learning

With its unprecedented range of professional features in its price class, the XA10 is a perfect teaching tool for media production. It is capable of operating in full AUTO and program modes like a consumer model, but offers students the opportunity to learn professional techniques with its XLR balanced-line sound inputs, phantom power, waveform monitor, 70-percent and 100-percent zebra patterns, multiple frame rates including 24p, and complete manual control of focus, exposure, and color balance. There is a lot of video technology that can be taught and learned with this camcorder.

Its ergonomic design, portability, and relative ease of use allow the teaching/learning situation to go beyond technology to concentrate on concepts. As a means of teaching yourself, or as assignments for a media class, it is possible to derive assignments from the production strategies discussed in this chapter. Here are some suggestions:

![]() Shoot an observational, slice-of-life Direct Cinema exercise. Tape approximately one hour of intimate hand-held observational video of a human-centered activity or event that would occur on its own. Edit it into a coherent five-minute Direct Cinema mini-documentary so that we feel we know the person(s) involved. It should be shot in such a way that the event itself engages us and tells its own story directly with no narration or interview as intermediaries.

Shoot an observational, slice-of-life Direct Cinema exercise. Tape approximately one hour of intimate hand-held observational video of a human-centered activity or event that would occur on its own. Edit it into a coherent five-minute Direct Cinema mini-documentary so that we feel we know the person(s) involved. It should be shot in such a way that the event itself engages us and tells its own story directly with no narration or interview as intermediaries.

![]() Shoot an interview portrait or an interview oral history documentary with B-roll on an assigned or self-selected topic. Use a similar ratio: an hour of video for a five-minute finished piece.

Shoot an interview portrait or an interview oral history documentary with B-roll on an assigned or self-selected topic. Use a similar ratio: an hour of video for a five-minute finished piece.

![]() Video Snapshot lends itself to short exercises and media assignments on the nature of montage. Classic montage is the process of making a statement through the dynamic juxtaposition and sequencing of images, constructing meaning by stringing a series of shorter shots together. What happens if you preset the camcorder for 2-second video snapshots but assign (or choose to shoot) completely different strategies for creating a metric montage of an event? If this is done as a class exercise, each person might be assigned the same topic or event. The differences will reveal how each has used metric montage. One person might construct a montage based on Eisenstein’s sense of collision, where each shot is considerably unlike the previous shot in composition, rhythm, or action. When a sequence is composed of opposing or contrasting elements, we feel the rhythmic change of every cut. Another person might shoot entirely in jump cuts by always keeping the same subject in frame for a sequence of 2-second discontinuous clips that jump from moment to moment. Another might try to build an action/reaction/insert/cutaway sequence while still being limited to 2-second shots.

Video Snapshot lends itself to short exercises and media assignments on the nature of montage. Classic montage is the process of making a statement through the dynamic juxtaposition and sequencing of images, constructing meaning by stringing a series of shorter shots together. What happens if you preset the camcorder for 2-second video snapshots but assign (or choose to shoot) completely different strategies for creating a metric montage of an event? If this is done as a class exercise, each person might be assigned the same topic or event. The differences will reveal how each has used metric montage. One person might construct a montage based on Eisenstein’s sense of collision, where each shot is considerably unlike the previous shot in composition, rhythm, or action. When a sequence is composed of opposing or contrasting elements, we feel the rhythmic change of every cut. Another person might shoot entirely in jump cuts by always keeping the same subject in frame for a sequence of 2-second discontinuous clips that jump from moment to moment. Another might try to build an action/reaction/insert/cutaway sequence while still being limited to 2-second shots.

The G10/XA10’s built-in Video Snapshot mode can pre-set an automatic limit of 2-, 4-, or 8-second shot lengths. As long as you are in Video Snapshot mode, which you enter by choosing FUNC > Video Snapshot > ON, your shots will be a predetermined length. As an indicator, a blue border appears on the touchscreen. (See Figure 17.3.) At the end of each snapshot, the screen momentarily blinks (an imitation of a shutter closing) to inform you that the shot has ended. You can turn off Video Snapshot by choosing FUNC > Video Snapshot > OFF. Changing the camcorder’s AUTO/M/ CINEMA switch also turns off Video Snapshot. To set the length of the snapshot, choose FUNC > MENU > Film Clip icon > Video Snapshot Length and select 2, 4, or 8 Seconds. It is also possible to assign a programmable button to turn on Video Snapshot. To do so, choose FUNC > MENU > Tool icon > Assign Button 1 or 2 and select Video Snapshot.

Figure 17.3 After activating Video Snapshot, the blue border remains on screen as a reminder you are in snapshot mode.

![]() A set of variations of this would be to produce a complete 30-second dramatic, documentary, event video, or experimental scene composed of exactly 15 clips of 2 seconds each. This could be shot in sequence, which for all practical purposes is “editing in the camera,” and the challenge would be to completely preconceive the project before shooting. Approached or assigned differently, the project could be edited, which will allow for a combination of production planning along with final shot selection and sequencing of images in postproduction. The project could be an entirely visual exercise with only silence or continuous music or ambience on the sound track. Alternatively, it could be accompanied by the original 2-second sound of each clip as recorded with the video, or a completely developed sound score with sync moments and Foley.

A set of variations of this would be to produce a complete 30-second dramatic, documentary, event video, or experimental scene composed of exactly 15 clips of 2 seconds each. This could be shot in sequence, which for all practical purposes is “editing in the camera,” and the challenge would be to completely preconceive the project before shooting. Approached or assigned differently, the project could be edited, which will allow for a combination of production planning along with final shot selection and sequencing of images in postproduction. The project could be an entirely visual exercise with only silence or continuous music or ambience on the sound track. Alternatively, it could be accompanied by the original 2-second sound of each clip as recorded with the video, or a completely developed sound score with sync moments and Foley.

![]() Create a video storyboard for a short fiction script shot with 2-, 4-, or 8-second video snapshots instead of stills. The shots can be viewed silently to show the visual flow of the storyboard, or can have a one-phrase or one-sentence voice-over description summarizing the dialogue or action in each shot.

Create a video storyboard for a short fiction script shot with 2-, 4-, or 8-second video snapshots instead of stills. The shots can be viewed silently to show the visual flow of the storyboard, or can have a one-phrase or one-sentence voice-over description summarizing the dialogue or action in each shot.

![]() What happens if the 2-second video snapshot is assigned or self-imposed as an obstruction for shooting or redoing a short dramatic script that was not intended for short fragments? Every shot will be of identical length, as predictable as a metronome. The challenge is to make this work effectively. See The Five Obstructions, where filmmaker Jørgen Leth had to do it with half-second shots.

What happens if the 2-second video snapshot is assigned or self-imposed as an obstruction for shooting or redoing a short dramatic script that was not intended for short fragments? Every shot will be of identical length, as predictable as a metronome. The challenge is to make this work effectively. See The Five Obstructions, where filmmaker Jørgen Leth had to do it with half-second shots.

![]() Use the camcorder to defamiliarize. Through cinematic means, transform a banal, commonplace experience by seeing it in a new way. Part of the challenge here is to create an engaging, coherent, and rewarding experience with a beginning, middle, and end. Macro videography is one way to enter a sensually visual and tactile world that goes beyond everyday experience. Infrared is another, provided you avoid imitations of the Blair Witch Project and cable TV stories of haunted houses and try to explore genuinely fresh possibilities with infrared. The defamiliarization exercise can be just as challenging in normal operating modes. Even without special devices, a palm-sized camcorder that you can take almost anywhere offers ways to explore the world with fresh eyes.

Use the camcorder to defamiliarize. Through cinematic means, transform a banal, commonplace experience by seeing it in a new way. Part of the challenge here is to create an engaging, coherent, and rewarding experience with a beginning, middle, and end. Macro videography is one way to enter a sensually visual and tactile world that goes beyond everyday experience. Infrared is another, provided you avoid imitations of the Blair Witch Project and cable TV stories of haunted houses and try to explore genuinely fresh possibilities with infrared. The defamiliarization exercise can be just as challenging in normal operating modes. Even without special devices, a palm-sized camcorder that you can take almost anywhere offers ways to explore the world with fresh eyes.

Production Apps for iPhone, iPod, and iPad

The iPhone, iPod, iPad and Android have become essential as aids for planning, organization, and various aspects of field production. Their size and mobility are perfectly suited to palm-sized production. Following are some selected apps that are particularly useful:

![]() DSLR Slate. Even though it is called “DSLR Slate,” this app works equally well with the G10/XA10. The slate provides a way to display for the camera essential information such as director, producer, project, scene, take, memory card, and date, as well as technical information such as exposure, aperture, shutter speed, and white balance. Recorded clips of this information are useful for continuity notes, retakes, future reference, and organizing. When there is more than a full frame of information to display, the slate will cycle info so that items can be viewed on successive video frames over a 2-second time span. When shooting double system sound or with multiple cameras, DSLR Slate provides a precise audio/video sync mark. It also includes a color chart and selectable timecode.

DSLR Slate. Even though it is called “DSLR Slate,” this app works equally well with the G10/XA10. The slate provides a way to display for the camera essential information such as director, producer, project, scene, take, memory card, and date, as well as technical information such as exposure, aperture, shutter speed, and white balance. Recorded clips of this information are useful for continuity notes, retakes, future reference, and organizing. When there is more than a full frame of information to display, the slate will cycle info so that items can be viewed on successive video frames over a 2-second time span. When shooting double system sound or with multiple cameras, DSLR Slate provides a precise audio/video sync mark. It also includes a color chart and selectable timecode.

![]() Easy Release. A release is a legal agreement between the media maker and the performer, documentary subject, crew member, or property owner giving permission for their recognizable image or other contribution to be used in the production. A release usually dissuades frivolous legal actions and can be used as evidence that consent had been given. It is a good practice to obtain releases for any production that will have exposure to venues other than a limited private audience. If you were to license, sell, distribute, or broadcast a production, you may be asked to demonstrate that it was produced with consent. Easy Release allows you to complete the entire release process on your iPhone, iPad, or Android. You can customize the wording of various kinds of standard releases and add your own data including contact information, personal signature, and even a logo. The app is then used on location to take contact information, a photo, and a signature of the subject(s) directly on the iPhone, iPad, or Android. Easy Release assembles these items into a well-formatted PDF document and automatically emails it to both the media maker and the subject.

Easy Release. A release is a legal agreement between the media maker and the performer, documentary subject, crew member, or property owner giving permission for their recognizable image or other contribution to be used in the production. A release usually dissuades frivolous legal actions and can be used as evidence that consent had been given. It is a good practice to obtain releases for any production that will have exposure to venues other than a limited private audience. If you were to license, sell, distribute, or broadcast a production, you may be asked to demonstrate that it was produced with consent. Easy Release allows you to complete the entire release process on your iPhone, iPad, or Android. You can customize the wording of various kinds of standard releases and add your own data including contact information, personal signature, and even a logo. The app is then used on location to take contact information, a photo, and a signature of the subject(s) directly on the iPhone, iPad, or Android. Easy Release assembles these items into a well-formatted PDF document and automatically emails it to both the media maker and the subject.

![]() Movie Slate. This app doubles as a clapper board and a digital slate for displaying production information, shot logs, and notes for shooting by the camera at the head or tail of a shot. It is useful for creating an audio/visual sync mark for slating double system sound with a separate video and audio recorder or providing a synchronization point when shooting with multiple cameras. You can customize its appearance, colors, and fonts. During production, it can also be used as an off-camera note pad for text, voice, photos, logging, and rating shots. This information can be later exported as a production log.

Movie Slate. This app doubles as a clapper board and a digital slate for displaying production information, shot logs, and notes for shooting by the camera at the head or tail of a shot. It is useful for creating an audio/visual sync mark for slating double system sound with a separate video and audio recorder or providing a synchronization point when shooting with multiple cameras. You can customize its appearance, colors, and fonts. During production, it can also be used as an off-camera note pad for text, voice, photos, logging, and rating shots. This information can be later exported as a production log.

![]() ProPrompter. In ProPrompter, scripts can be imported or typed within the application and then paused or scrolled at controllable speeds as a teleprompter. An iPhone or iPad can be held next to the camcorder for simple teleprompter operation, mounted on a bracket, or incorporated into a professional two-way mirror and anti-reflection hood (which the company also sells) for reading a script while looking directly into the lens.

ProPrompter. In ProPrompter, scripts can be imported or typed within the application and then paused or scrolled at controllable speeds as a teleprompter. An iPhone or iPad can be held next to the camcorder for simple teleprompter operation, mounted on a bracket, or incorporated into a professional two-way mirror and anti-reflection hood (which the company also sells) for reading a script while looking directly into the lens.

![]() Storyboard Composer. Cinemek Storyboard Composer is compatible with iPhone, iPod Touch, and iPad. To pre-visualize your production, you can import photos or drawings or take photos within the application itself. The app also supplies a library of pre-existing graphic figures if you need them. Storyboard Composer allows you to crop, scale, rotate, and arrange the visuals with various panel options to which you can add zooms, pans, shot numbers, arrows, labels, notes, and audio. It provides a mobile reference that can be used on location while setting up shots. The storyboards can be exported to PDF, sent by email, or viewed on the mobile device as individual panels, multiple panels, or an animatic (a real-time storyboard slide show with a sound track).

Storyboard Composer. Cinemek Storyboard Composer is compatible with iPhone, iPod Touch, and iPad. To pre-visualize your production, you can import photos or drawings or take photos within the application itself. The app also supplies a library of pre-existing graphic figures if you need them. Storyboard Composer allows you to crop, scale, rotate, and arrange the visuals with various panel options to which you can add zooms, pans, shot numbers, arrows, labels, notes, and audio. It provides a mobile reference that can be used on location while setting up shots. The storyboards can be exported to PDF, sent by email, or viewed on the mobile device as individual panels, multiple panels, or an animatic (a real-time storyboard slide show with a sound track).

![]() Teleprompt+ for iPad. Teleprompt+ turns the iPad into a professional teleprompter that can import, type or edit scripts, and format them for being read aloud. It provides a countdown, cues, arrows, highlighted text, and controllable scrolling speeds. Like ProPrompter, text can be read directly from an iPad held or mounted near the camcorder. Alternatively, Teleprompt+ can display in mirror mode for speaking directly on–axis toward the lens if used with a two-way mirror rig (a beam splitter) available from other sources.

Teleprompt+ for iPad. Teleprompt+ turns the iPad into a professional teleprompter that can import, type or edit scripts, and format them for being read aloud. It provides a countdown, cues, arrows, highlighted text, and controllable scrolling speeds. Like ProPrompter, text can be read directly from an iPad held or mounted near the camcorder. Alternatively, Teleprompt+ can display in mirror mode for speaking directly on–axis toward the lens if used with a two-way mirror rig (a beam splitter) available from other sources.

Green Media Making

Within production planning, you should also examine alternative materials and environmentally friendly practices. These include looking into recycling, reducing waste, purchasing locally made products, donating unused or unwanted items, and offsetting the carbon dioxide and pollutants we generate in making a production.

Working with a palm-sized camcorder and the minimal support equipment it needs is a step in this direction. Using augmented available light instead of 2,000–20,000 watts for each scene is a considerable energy savings. LED lights are highly efficient per watt. They last 20,000 to 50,000 hours and do not contain mercury as fluorescents do. Exhibiting productions online or uploading copies via the Internet (even if this is simply limited to preview copies) uses far fewer resources than individual copies burned onto DVDs that are shipped in plastic cases surrounded by padding and cardboard mailers. Media distributors themselves have turned to online as a major delivery system for the digital age.