10

Team Building

This chapter is contributed by Hans J. Thamhain, Bentley College.

A castle is only as strong as the people who defend it.

Sun Tzu—The Art of War

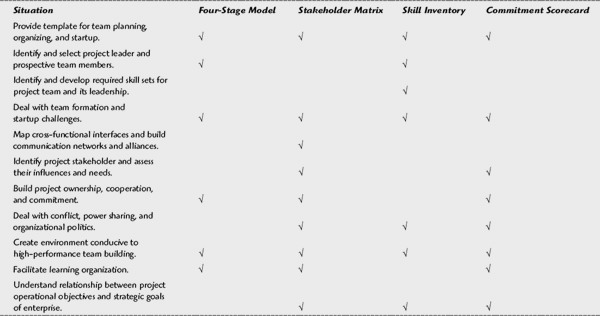

This chapter focuses on the tools for identifying, organizing, and developing the project team:

- Four-Stage Model of Project Team Building

- Stakeholder Matrix

- Skill Inventory

- Commitment Scorecard

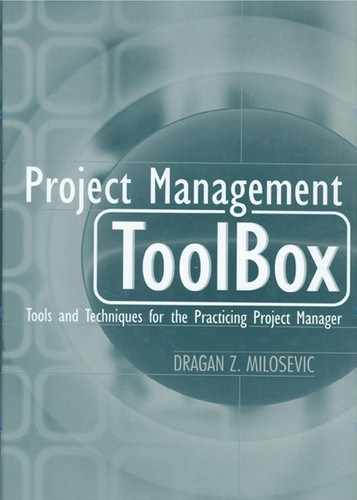

Figure 10.1 The role of team-planning tools in the standardized project management process.

These tools focus specifically on the human side of project planning, helping to analyze the resource requirements, and to identify, recruit, and build the people needed into a unified, high-performing project team. In addition, many of today's projects require team building as a continuing process throughout their life cycles. Therefore, consistent with the broad concept of stakeholder management and the need for developing learning organizations, these tools overlap other phases of the standardized PM process shown in Figure 10.1. The purpose of this chapter is to help practicing and prospective PM professionals to

- Understand and build the skills needed to function effectively on their project teams.

- Select project leaders and team members.

- Build cross-functional communication networks and alliances.

- Deal with conflict and power sharing.

- Build project ownership and commitment.

- Develop a learning organization.

Mastering these tools is part of the core competencies of PM and is necessary for effectively leveraging company resources toward established business objectives.

Four-Stage Model of Project Team Building

What Is the Four-Stage Model of Project Team Building?

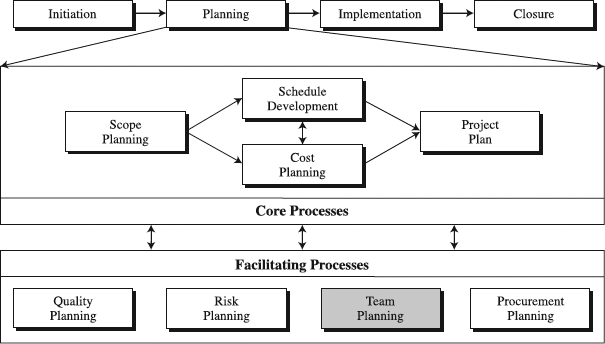

The Four-Stage Model is a tool for organizing and systematically developing project teams. The concept was originally suggested by B.W. Tuchman in 1965 [2], who identified four stages that all teams have to pass through in their transformation to a unified, effective work team: Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing. Each stage is associated with specific characteristics, team activities, and managerial guidance. The concept has been refined and developed by many, most noticeably by P. Hershey and K. Blanchard [3]. Today, the Four-Stage Model enjoys wide acceptance as a powerful tool for team planning and development. It often becomes the starting point for identifying critical success factors, skill profiles, and potential team members. It also serves as a roadmap for project team development. The model shares a “phase-based” philosophy as part of contemporary PM approaches, such as the rolling wave concept, phased developments, phase reviews, voice–of–the customer, and stage-gate developments. The basic structure of the Four-Stage Model is shown in Figure 10.2. Inputs to each stage come from both the organizational and project environment. These inputs affect the team formation process and its subsequent development. They also affect the team dynamics, measured in critical success factors, decisions, action items, and resource requirements.

Figure 10.2 Four-stage model of project team building.

Constructing the Four-Stage Model

As shown in Figure 10.2, the team development model is typically presented as a series of four serial steps: forming, storming, norming, and performing. However, its application is for both serial and parallel work processes, including concurrent engineering, design-builds, fast tracking, rolling wave developments and multiorganizational joint developments. The labels for each step can be chosen differently and the number of steps can be varied. For each stage, a set of management parameters should be defined. At the minimum, these parameters should include (1) critical success factors, important for the team to perform effectively, (2) decisions to be made by management, the team and joint decisions, with responsible individuals and timelines clearly defined, (3) action items to be taken by management, the team and joint actions, with responsible individuals and timelines clearly defined, (4) resources required and their approval process, and (5) specific results to be delivered during, or toward the end of the stage.

Preparing Information Inputs. Involvement of all stakeholders is important! To be meaningful and realistic, inputs for these stage/management parameters should come from a broad spectrum of stakeholders, including team members, functional support groups, company management, contractors, partners, and customers. However, at the formation of the project and its team, the known stakeholder population is small, but it increases with the progression of the project through its life cycle. Efforts should be made at any stage to reach into the various groups of stakeholders to cast the widest possible net for input gathering. Specific group communication tools, such as brainstorming, focus teams and nominal group technology, can support the input data gathering process and help in organizing the information into a meaningful and reliable set of management parameters as a basis for organizing and developing the project team.

Communicating the Team Organization. The evolving project team organization should be documented as part the project plan, and updated as the project moves through its life cycle. Conventional tools such as (1) task roster, (2) task matrix or responsibility matrix, (3) N-square interface chart, and (4) Project Charter can be useful to document and communicate task responsibilities and their organizational interfaces.

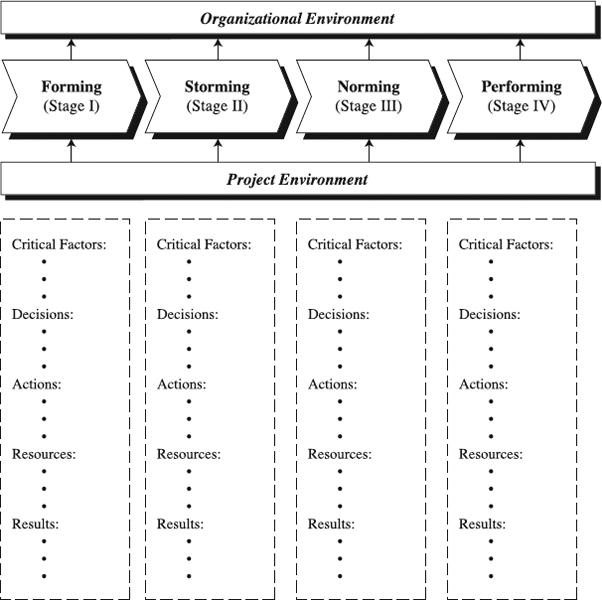

Team Characteristics and Leadership during Team Development. The characteristics of the workgroup changes as it goes through the stages of development. Therefore, team leadership style and effectiveness depend on the project situation and stage. At the beginning of the team formation, a more directive management style is needed than during the later stages when the team is approaching maturity. To provide additional guidelines for developing the inputs for the Four-Stage Model, following are descriptions of each stage, together with some leadership perspective shown in Figure 10.3 that summarizes Hershey and Blanchard's [3] popular model of team leadership:

Figure 10.3 Leadership style versus team integration level.

- Forming stage. At this stage, core team members are being defined and introduced to the project and its mission. Communication flows by and large one way, from the designated project leader, senior management or the project sponsor, to the emerging team members. The emerging workgroup is not yet a team, but just a collection of people from different organizations and functional backgrounds. Anxieties, confusions, and role ambiguities are predictably high in this stage, while mutual trust, respect, task involvement, and commitment are very low. This stage requires a leadership style that relies on clear directions, guidance, strong image building, vision sharing, close supervision, and considerable top-down decision making.

- Storming stage. At this stage, also called the startup stage, many of the project team members have been defined and signed on to the project. Members of the workgroup begin to get involved with the project assignment, try to understand the project scope and requirements, and sort out specific roles and responsibilities. As projects success often depends on innovation, cross-functional teamwork, member-generated performance norms, and decision making, the team must work out highly complex processes of work integration and deal with the issues of self-direction and control. At this stage, the team usually experiences very high degrees of anxieties and conflict, while mutual trust, respect, task involvement, and commitment are lowly evolving. Typical questions that should be expected to be asked by team members and addressed by team leaders are listed in the box that follows, “Typical Questions to Be Addressed During Storming Stage”). However, in addition, project leaders must pay much attention to the human side, dealing effectively with the high levels of conflict, facilitating interactions among team members, building cross-functional interfaces, providing feedback, and fostering an environment conducive to mutual trust and respect, buy-in, and purpose. Hershey and Blanchard [3] define this mixture of “directive and relationship-oriented leadership” as “selling style.”

- Norming stage. At this stage, which is also called the “partial performing stage,” most team members have been signed on and are working as an integrated work team toward the project objectives. Team members begin to feel comfortable with their roles and assignments, and rely on other members’ expertise. The team as a whole starts to unify and enjoys the team environment. Mutual trust, respect, task involvement, and commitment to established goals strengthen during this stage together with communication effectiveness throughout the project organization and its interfaces. Expertise-based decision making and leadership begin to emerge, allowing the project manager to share power with the team members and to encourage a broad range of self-direction and control. However, project leaders must still pay strong attention to the human side, building confidence in the team capability, dealing effectively with issues of workload, performance measures, interfaces, and integration. The project manager must continue the team building process toward the performing stage that characterizes the fully integrated, high performing team.

- Performing stage. At this stage, the team is highly unified and committed to achieve the established project objectives. By definition, a team that reached the performing stage becomes “self-directed” as described in the box that follows. Leadership evolves from within the team based on trust, respect, and credibility. The need for external supervision and administrative support is minimum. Yet maintaining this very delicate balance of power and control requires highly sophisticated PM skills and leadership, and active support by senior management.

Utilizing the Four-Stage Model of Project Team Building

When to Use. The model is useful for project team development at any point during the project life cycle. However, its benefits are especially leveraged during the early phases of project and team formation. This is the time period of “forming” and “storming,” which is by-and-large ineffective with regard to producing any useful deliverables, a time period that should be minimized to benefit cost, time to market, and strategic focus. From yet another perspective, the model is especially recommended for organizing and developing teams of large, more complex, and technology-intensive projects. However, regardless of project size and complexity, the use of the model will expedite the team formation and ultimately improve overall project performance. The final output from the Four-Stage Model is a team development plan.

Typical Questions to Be Addressed During Storming Stage

- What are the specific objectives to be achieved with this project?

- Who is in charge?

- Whom do I report to? What kind of dual accountabilities do I have?

- What is the priority of this project and the management commitment to it?

- What communication channels exist?

- What type of project procedure, plan, or protocol do we follow?

- What type of project reviews are being expected and when in the project cycle should they occur?

- What factors are critical for project success?

- What are our roles and responsibilities regarding tasks and interfaces with other functions?

- How is our performance being evaluated and who does the evaluation?

- Is this project work part of my career path or a diversion?

- What kind of conflict should be expected and who will resolve it?

- How can problems be escalated?

- What kind of training and help is available?

- How do we deal with risks and uncertainties?

Time to Develop. The Four-Stage Model can be used at different points in the project life cycle, each one with a different purpose and different time requirement.

Self-Directed Teams

Definition. A group of people chartered with specific responsibilities for managing themselves and their work, with minimal reliance on group-external supervision, bureaucracy and control. Team structure, task responsibilities, work plans, and team leadership often evolve based on needs and situational dynamics.

Benefits. Ability to handle complex assignments, requiring evolving and innovative solutions that cannot be easily directed via top-down supervision. Widely shared goals, values, information, and risks. Flexibility toward needed changes. Capacity for conflict resolution, team building, and self-development. Effective cross-functional communications and work integration. High degree of self-control, accountability, ownership, and commitment toward established objectives.

Challenges. A unified, mature team does not just happen, but must be carefully organized and developed by management. A high degree of self-motivation, and sufficient job, administrative, and people skills must exist among the team members. Empowerment and self-control might lead to unintended results and consequences. Self-directed teams are not necessarily self-managed, they often require more sophisticated external guidance and leadership than conventionally structured teams.

- Initial modeling of team formation and startup. This could be a single-handed effort by the project manager, thinking through the issues, and writing down critical issues and requirements. Time required: 30 minutes.

- Detailed modeling of team formation and startup. This can be accomplished by a small group of initially available team members or core team members, including the project manager and functional support managers. Brainstorming, focus grouping, and benchmarking of previous team developments will lead to a team development plan. Time required: 2 to 4 hours.

- Team-generated development plan. This is the most effective, most beneficial, but also most time-consuming use of the tool. All team members participate in brainstorming, focus grouping, and benchmarking of previous team developments, which will lead to a team development plan. Time required: 3 to 6 hours.

Benefits. With today's demands on high efficiency, speed, and quality, project teams have become increasingly more important for dealing with the technical complexities, cross-functional dependencies, and need for innovative performance. The Four-Stage Team Development Model is often being used by managers as a framework for analyzing the team development process. It has become an important tool for supporting the organization and development of multifunctional teams that can effectively deal with these challenges.

Advantages and Disadvantages. Advantages include the following:

- Provides a template for visual summary of the team organization and development process.

- Involves team members and management in critical thinking about needs, processes, and requirements for effective teamwork and project execution.

- The team involvement itself provides a vehicle for building mutual trust, respect and commitment.

- Helps in understanding of project objectives, requirements, challenges, and benefits.

- Provides a tool for continuing team development and organizational learning.

Disadvantages include the following:

- Considerable time and leadership skills required for developing team-generated inputs.

- Potential for conflict and power struggle during team sessions.

- Differences in organizational culture and value may emerge and need to be dealt with.

- Implementation of team development plan may be impossible, leading to frustration and disillusion.

Variations. Many variations of the Four-Stage Team Development process exist. For the template, a different number of stages may be used, and input-output parameters can vary to accommodate the specific needs of the project organization. A common variation is the “merger” of stages, combining “forming and storming,” “norming and performing,” or both. Also, the process of information gathering, team involvement, and plan implementation varies a great deal among organizations to accommodate special organizational needs.

Customize the Four-Stage Model of Project Team Building. An effort should be made to make the model consistent with both the business process of the company and any established PM process. The model, its team development process, and resulting plan will be more readily accepted by the project team and company management if it is relevant to the business environment. Especially sensitive to company culture are the number of stages and their labels. For example, the change of Stage II from “storming” to “clarifying” or “starting” can make a big difference regarding participants’ perception of purpose, expected behavior, and results. Similar to any other organizational development, the basic framework and process, the four-stage model should be carefully defined by senior project personnel and management, and tested in pilot runs, before it is endorsed as a formal team-building tool. However, project leaders can take the initiative of using the principle components of the four-stage process in support of their team formation and development efforts, although the process has not yet been formally established.

Four-Stage Model of Project Team Building Check

Make sure that the Four-Stage Model is properly structured and effectively applied. With it, you should be able to

- Develop the basic model framework and process with senior management and project professional involvement.

- Initially, run model in pilot mode, fine-tune, and issue a simple procedure.

- Ensure consistency of the model and its process with the business environment and established project system.

- For each stage input, involve as many team members and their interfaces as possible.

- Make the team part of the resulting team development plan; obtain buy-in to process and results.

- Focus increasingly on cross-boundary relations, delegation, and commitment.

- Facilitate continuous organizational learning and improvement, and fine-tune the model and its process.

Summary

The Four-Stage Model supports project team startup and development efforts. It helps to deal with the enormous managerial challenges of organizing, directing, and controlling teamwork in our increasingly complex project environments. The model helps in identifying the resources needed and creating the involvement necessary for unifying the workgroup toward an effective, objective-focused team. In addition, effective project leaders use the model to take preventive actions early in the project life cycle, and the model fosters a work environment that is conducive to team building as an ongoing process. Customizing the model for a specific organization requires leadership and inputs from both the PM system and top management.

Stakeholder Matrix

What Is the Stakeholder Matrix?

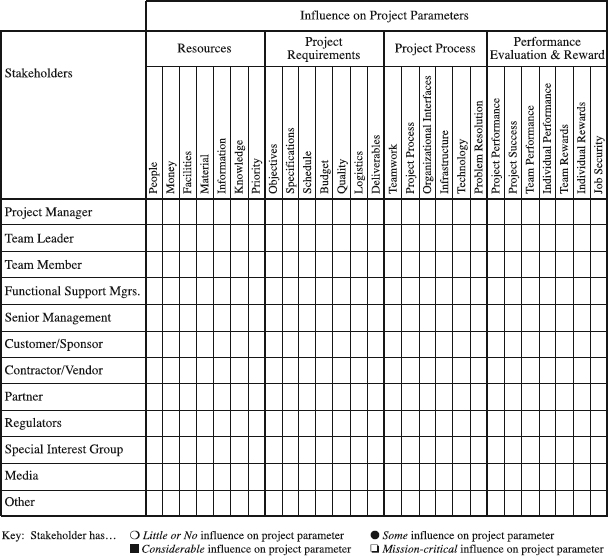

The Stakeholder Matrix is a tool for systematically identifying and developing the total project team. The matrix recognizes the complexity of project communities that include many stakeholders, ranging from host organizations to support groups, experts, vendors, customers, special interest groups, and regulators [4]. It provides a framework for profiling the broad spectrum of stakeholders and the degree to which they influence project success. Project success and performance often depends on factors that exceed the boundaries of traditional contracts and PM [5]. These factors include the goals, needs, and ambitions of the many parties and individuals that hold an interest in the project and its outcome. To be successful, project leaders must understand the needs and influences of these stakeholders and be able to leverage their resources most favorable toward the goals and ultimate success of the project. The matrix provides a framework for assessing the needs and expectations of all major project stakeholders, and thus helps in managing potential contributions and customer relations of the project community. The Stakeholder Matrix has its conceptional roots in the task matrix with contemporary extensions to Affinity Diagrams such as the KJ methodology (for discussion and applications of the KJ method, see Zien and Buckler [6]). Its topology is shared by many other interface management tools, such as project interface definitions, project management readiness plan, voice of the customer, quality function deployment, and customer relations management. The basic structure of the Stakeholder Matrix is shown in Figure 10.4.

Constructing the Stakeholder Matrix

As shown in Figure 10.4, the Stakeholder Matrix is a two-dimensional grid. One side of the matrix lists the project stakeholders, while the other side lists the various influence factors to project success. Figure 10.4 shows typical examples of stakeholders and success factors and provides a good template for data collection. However, project leaders must determine the actual and specific stakeholders, influence factors, and their degree of associations.

Figure 10.4 Stakeholder Matrix.

Preparing Information Inputs. To be meaningful and realistic, inputs for the Stakeholder Matrix should come from a broad spectrum of senior personnel who understand specific segments of the stakeholder community. After the set of stakeholders and influence parameters has been identified, the degree of stakeholders' influence on project success should be determined and recorded for each interface point. A simple three or four-point scale, such as shown in the legend of Figure 10.4, is suggested to record the degree of influence on each project parameter. Group communication tools, such as brainstorming, focus groups, and Delphi techniques, can help in supporting the input data gathering process.

Communicating Stakeholder Influences. The Stakeholder Matrix should be documented, either separately or as part the project plan and updated as the project moves through its life cycle. It is important to ensure that the Stakeholder Matrix is consistent with other interface documents, such as the task roster, task matrix, N-square interface chart and customer relations management tools, used within the project organization. In addition to simply showing stakeholder influences, a stakeholder influence grid can be generated to support the management of stakeholder relations, as shown in the box that follows, “Stakeholder Influence Grid.”

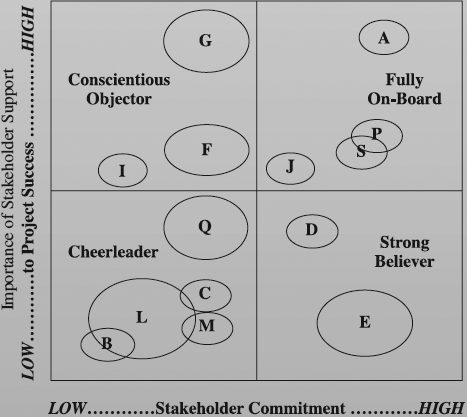

The influences of various stakeholders on project parameters can be mapped from the Stakeholder Matrix into the stakeholder influence grid (see Figure 10.5). The grid shows for each stakeholder (a) the importance of support and (b) level of commitment. In the example on the left, the A, B, and C bubbles indicate different stakeholders, and the bubble size indicates the degree of influence the stakeholder is perceived with. The grid divides stakeholders into four principle categories:

- Fully on board. Stakeholders who are very important to project success and are fully committed.

- Conscientious objector. Stakeholders who are very important to project success but are not committed.

- Strong believer. Stakeholders who are very committed but are not too important for project success.

- Cheerleader. Stakeholders who are neither important nor committed.

As a refinement, the grid map can show the “current” and “desired” position.” The grid can be used to manage stakeholder relations.

Figure 10.5 Stakeholder influence grid.

Utilizing the Stakeholder Matrix

When to Use. The Stakeholder Matrix is especially useful during the early stages of project team formation and team planning. It provides a tool for identifying the diverse set of key players of the project organization, their influences on the various project parameters and success criteria. The Stakeholder Matrix becomes the framework for developing project interface plans and stakeholder relation management plans as part of the overall team development plan, the guiding document for optimizing team integration and effectiveness throughout the project life cycle.

Time to Develop. The Stakeholder Matrix can be developed in two stages:

- Initial matrix setup. This could be accomplished single-handedly by the project manager, defining the key stakeholders and their impact on principle project parameters. Time required: 30 minutes.

- Detailed matrix setup. This includes the fine-tuning and validation of the diverse spectrum of stakeholders and an in-depth assessment of the influences on project parameters. This can be accomplished by a small group of senior people familiar with the project interfaces. The involvement of stakeholders from the outside of the core team can be especially beneficial in getting a realistic perspective. These stakeholders include functional support groups, customers, contractors, and community interest groups. Brainstorming, focus grouping, Delphi, and benchmarking of similar previous projects will lead to a detailed Stakeholder Matrix. Time required: 2 to 4 hours.

Benefits. Successful project teams know how to build cooperative networks and mutually beneficial alliances among all project stakeholders. The Stakeholder Matrix provides a simple tool for the project team to identify and assess the stakeholder influences on specific project parameters. The matrix also provides a framework for the team to identify the conditions necessary for obtaining stakeholder cooperation and commitment in exchange for fulfilling certain needs and wants, a contemporary management concept described as “currency exchange” [7]. The Stakeholder Matrix has become an important contemporary tool for dealing effectively with the intricate web of relations involved in today's project situations, and to build a unified, committed project team that includes all stakeholders.

Advantages and Disadvantages. Advantages include the following:

- Provides a template for summarizing the stakeholders and their influences on project parameters.

- Provides a framework for mapping project interfaces and organizational currencies.

- Provides a framework for building the total project team and for managing stakeholder relations.

- Provides a framework for managing projects in the context of company strategy.

- Helps in dealing with project stakeholders proactively to resolve potential problems, conflicts and contingencies.

- The Stakeholder Matrix development and its application creates an environment conducive to team building and organizational learning.

Mapping Organizational Dependencies

The Stakeholder Matrix can be helpful in mapping dependencies among project team members, support organizations, customers, and other project stakeholders. This is an important step in building the social network necessary for effective interaction of all players toward project success. The Stakeholder Matrix helps to address the important questions such as:

- Whose support and cooperation do we need?

- What organizational conflicts exist between stakeholders?

- Do we have the necessary commitment from a critical support group?

- Who will resolve certain problems?

- What lines of communications exist among interfaces?

- What currencies do we have to influence our stakeholders?

- Do we involve the right people from the ABC special interest group?

- How can we help to build the influence of the KLM team?

- How can we build the influence over resource Q?

- How can we strengthen communications across interface ITF?

- Whose agreement do we need to proceed?

- Who are the key decision makers for this release?

- Whose opposition should we expect?

- What relationship do we have with PQR?

- What alternatives do we have to resource X?

- How do we share these responsibilities with XYZ?

- How do these people evaluate our performance?

Disadvantages include the following:

- Some time and leadership skills are required for developing matrix inputs.

- Considerable time and leadership are required for mapping Stakeholder Matrix data into stakeholder influence grid, team development plan, or project success factor analysis [8].

- Potential for conflict over different perception of stakeholder profile.

- Overreliance on the Stakeholder Matrix for PM.

- The matrix may lose relevancy in changing project environment unless continuously updated.

Variations. Many variations exist in the structure and application of the Stakeholder Matrix. For example, matrix entries can be shown in a more or less quantitative way, such as using alpha or numerical weights, or graphical symbols. Stakeholders can be described “generically,” as shown in Figure 10.4, or listed individually. The task matrix format is often being used to summarize stakeholder information. The largest variations are being seen in the graphical presentation of stakeholder relations, such as the stakeholder influence grid (shown previously in the chapter in the box) that derive from the matrix. These charts and graphs map stakeholder influences, management actions, project success criteria, currencies, and other parameters of the project environment in an attempt to build a project success model and to build a winning team. Yet another common variation is the rank ordering of stakeholder parameters [8, 9].

Customize the Stakeholder Matrix. The matrix should be structured to be conducive for capturing the most relevant information for developing the total team, its interfaces, and its stakeholder relations. A thorough understanding of the project environment and business strategy is necessary to define the most relevant matrix parameters that impact project performance. The value of the Stakeholder Matrix is in its application as a team-building tool. To be effective as a team development tool, members of the project community must see themselves as critical players in the project execution. The matrix and its derivative documents must highlight the visibility of these team members and help them to interact and solve problems.

Summary

The Stakeholder Matrix supports team planning and development effort with an emphasis on cross-functional interfaces and relationship building. The matrix helps in identifying the project stakeholders and their influence on the various project parameters, and as such, it becomes a catalyst for developing more comprehensive interface maps and team development plans. In addition, project leaders use the matrix to benchmark team interface performance and organizational development needs.

Stakeholder Matrix Check

Make sure that the Stakeholder Matrix is properly structured and effectively applied. With it, you should be able to

- Identify the elements for each matrix axis: (1) stakeholders and (2) project parameters; then group the elements into categories.

- Mark the degree of stakeholder influence on various project parameters.

- Indicate the degree of influence symbolically or numerically, without “micro-detailing.”

- Develop the matrix in multiple steps: first a single-handed, broad overview of stakeholders and project parameters, then involvement of core team members and project interface personnel.

- The axes of the Stakeholder Matrix should be consistent with the actual project organization. Customization of the template shown in Figure 10.5 is absolutely necessary.

- Use the matrix as an information source and catalyst for developing more comprehensive interface maps and team development plans.

- Involve the total project team in the Stakeholder Matrix development and share the final document with all team members.

- Focus the matrix application on cross-boundary relations management, organizational learning, and improvement.

Skill Inventory

What Is the Skill Inventory?

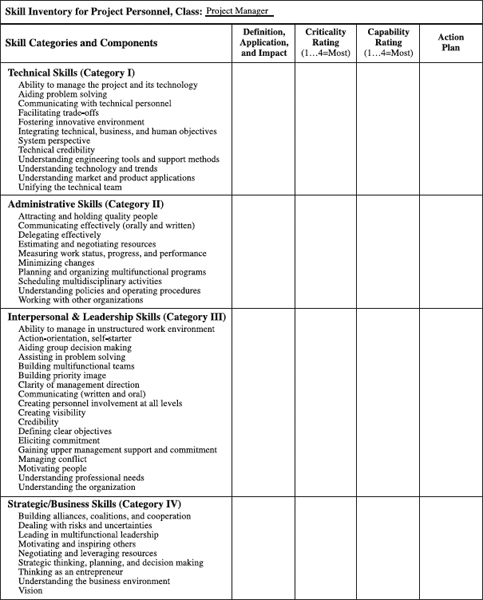

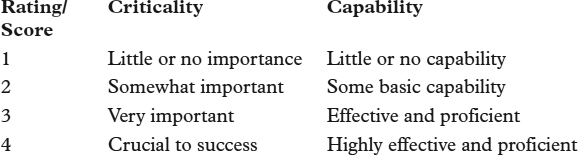

The Skill Inventory is a tool for systematically identifying the skill sets needed by project team members and their leaders. The concept can be used for identifying or benchmarking work skills of any job category or organizational level. It can also be used for personnel assessment and development, team building and broad-scale organizational development. Skill Inventories are an effective starting point for project team planning, staffing, and startup. They span across the strategic domain of PM, connecting the operational area of teamwork with the resource infrastructure of the organization. The basic structure of the Skill Inventory is shown in Figure 10.6.

Figure 10.6 Sample Skill Inventory for a project manager.

Constructing a Skill Inventory

As shown in Figure 10.6, the Skill Inventory is a listing of skill set components for one particular class of personnel. The skill components are grouped into categories, breaking down the complexity of the listing and providing a better overview and analysis of the skill sets. For each skill component, the table provides space for recording a criticality rating and a capability rating. These are judgment factors of (1) how important each skill component is to team performance and project success and (2) the level of current capability with the particular class of personnel or person under consideration. While under special circumstances elaborate rating schemes can be developed, it is suggested to keep the rating scale simple. A four-point Likert-type scale, as shown in the following, may be sufficient for rating the skill criticality and capability level respectively, and is often more effective than an “over-designed” scoring system:

In addition to the criticality/capability scoring, the Skill Inventory table provides two columns for recording references to other documents, such as skill definitions, impact assessments and action plans for skill development.

First-Time Construction. When the Skill Inventory template is constructed for the first time, the specific skill categories and components must be defined for each class of personnel, such as project manager, senior designer, marketing specialist, and so on.

Subsequent Applications. Once established, the template can be used with a minimum of fine-tuning to fit a new project situation. As a guideline, it is recommended to use the four skill categories listed in the sample inventory of Figure 10.6 as a framework for defining the specific skill sets required for a given personnel class and project situation:

Skill Category I: Technical Skills

Skill Category II: Administrative Skills

Skill Category III: Interpersonal & Leadership Skills

Skill Category IV: Strategic/Business Skills

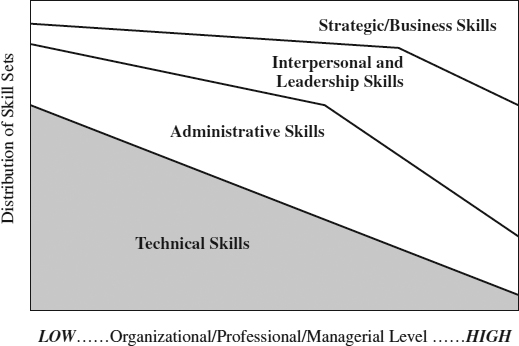

A general description of the four skill categories is given in the box that follows, “Grouping Skill Sets into Categories.” In addition, Figure 10.7 illustrates the relative distribution of skills with increasing managerial responsibilities. The focus, dominance, and criticality of skills shifts from “technical” to “administrative” and eventually to “interpersonal/leadership” and “strategic/business” skills, as the person assumes increasing managerial responsibilities and moves to higher organizational levels. Taken together, the Skill Inventory shown in Figure 10.6 for a project manager, and also fitting for a typical project team, provides a good overall format and convenient starting point for developing or customizing the Skill Inventory, and developing project managers toward the high-performance profile as shown in the text sidebar “Leadership Profile of Project Managers.”

Preparing Information Inputs. Both the skill set definition and scoring can be done individually or in groups. To be most meaningful and realistic, however, inputs for the Skill Inventory should come from a broad spectrum of the project community, from people who understand the specific skill requirements and can judge the current level capabilities. After the skill sets have been defined (or fine-tuned) under each of the four categories, the rating of each skill component and action planning can begin.

Inventory for Individual and Group Resources. Skill Inventories can be generated for and applied to

- Individual resources such as project managers

- Groups, such as R&D, product development group, or the whole project team.

Figure 10.7 Relative distribution of skill sets.

Grouping Skill Sets into Categories

Today's complex, multifaceted, and technology-oriented projects require sophisticated skills in project planning, organizing, and integrating multidisciplinary activities. Organizations are changing into flatter, more flexible structures with higher degrees of power-sharing, distributed decision making, intricate communication channels, and a self-directed workforce. All of this requires more sophisticated skill sets at all organizational levels. Further, project leaders must be competent both technically as well as socially, understanding the culture and value system of the organization in which they work. The days of managers who get by with only technical expertise or pure administrative skills are gone.

There is no magic formula that guarantees success in managing technology-based organizations. But research shows consistently [10, 11] that high-performing PM professionals have specific skills that can be grouped in four principle categories:

- Technical skills

- Administrative skills

- Interpersonal skills and leadership

- Strategic/business skills

Technical Skills. Most projects involve specialized multifunctional work. Project leaders rarely have all the technical expertise involved in the project execution. Nor is it necessary or desirable that they do so. It is essential, however, that project managers and team leaders understand the associated technologies, their trends, the markets, and the business environment so they can participate effectively in the search for integrated solutions. Without this understanding, the consequences of local decisions on the total program, the potential growth ramifications, and relationships to other business opportunities cannot be foreseen by the manager. Furthermore, technical expertise is necessary to communicate effectively with the work team, to assess risks, and to trade off on cost, schedule, and technical issues.

Administrative Skills. Administrative skills are essential. Project leaders must be experienced in planning, staffing, budgeting, scheduling, performance evaluations, and control techniques. While it is important that project leaders understand the company's operating procedures and the available tools, it is often necessary for these senior people to free themselves from the administrative details.

Interpersonal Skills and Leadership. Effective leadership involves a whole spectrum of skills and abilities: clear direction and guidance; ability to plan and elicit commitments; communication skills; assistance in problem solving; dealing effectively with managers and support personnel across functional lines often with little or no formal authority; information-processing skills, the ability to collect and filter relevant data valid for decision making in a dynamic environment; and ability to integrate individual demands, requirements, and limitations into decisions that benefit the overall project. It further involves the manager's ability to resolve intergroup conflicts and to build multifunctional teams.

Strategic/Business Skills. These skills involve the ability to see the business as a whole and to direct and monitor its overall performance. It includes components such as understanding the nature of the industry and having a general manager's perspective and business sense. These skills relate to policy decisions, strategic thinking, and long-term objectives. These skills are critical for shaping organizational directions and leveraging organizational resources. Knowledge in the area of systems theory, strategic planning, and general business management provides the foundation and supporting tools of this skill area.

Leadership Profile of Project Managers

- Bringing together the right mix of competent people which will develop into a team

- Building lines of communication among task teams, support organizations, upper management, and customer communities

- Building the specific skills and organizational support systems needed for the project team

- Coordinating and integrating multifunctional work teams and their activities into a complete system

- Coping with changing technologies requirements and priorities while maintaining project focus and team unity

- Dealing with anxieties, power struggle, and conflict

- Dealing with support departments; negotiating, coordinating, integrating

- Dealing with technical complexities

- Defining and negotiating the appropriate human resources for the project team

- Encouraging innovative risk taking without jeopardizing fundamental project goals

- Facilitating team decision making

- Fostering a professionally stimulating work environment where people are motivated to work effectively toward established project objectives

- Integrating individuals with diverse skills and attitudes into a unified workgroup with unified focus

- Keeping upper management involved, interested, and supportive

- Leading multifunctional task groups toward integrated results in spite of often intricate organizational structures and control systems

- Maintaining project direction and control without stifling innovation and creativity

- Providing an organizational framework for unifying the team

- Providing or influencing equitable and fair rewards to individual team members

- Sustaining high individual efforts and commitment to established objectives

How Many Skill Inventories Do We Need? To minimize proliferation of forms and plans, usually only a small number of Skill Inventories are being used, covering broad segments of the project community. Often only one Skill Inventory is being generated and maintained for the entire project team. Alternatively, Skill Inventories are being generated for the project leader and each of the major team segments, such as R&D, development, and operations. For first-time users, a single Skill Inventory, covering the entire project team, is recommended to simplify the process, optimize user benefits, and minimize frustrations over administrative overhead and personal conflict. A simple four-point scale, such as shown in Figure 10.6, is suggested to record the skill criticality and current capability level as a basis for team development planning. Group communication tools, such as brainstorming, focus groups, and Delphi techniques can help in supporting the data gathering process.

Communicating the Skill Inventory. The Skill Inventory should be documented, either separately or as part the project plan, and updated as the project moves through its life cycle. It is important to ensure that the Skill Inventory is consistent with other documents, such as the project charter, task roster, task matrix, and customer relations management tools, used within the project organization.

Utilizing the Skill Inventory

When to Use. Skill Inventories are useful tools for identifying, assessing, and developing the project team and leveraging its resources. The tool can be especially beneficial during the early stages of project team formation and team planning. It provides a framework for identifying the skill sets and capabilities needed for effective teamwork with perspective on the criteria for project success. The Skill Inventory helps in the process of identifying and selecting team members, and in developing their skill sets as needed. The Skill Inventory also connects the team's capabilities with the business requirements, and as such, it provides a strategic link between the operational and strategic components of the company. In this context, the Skill Inventory provides additional perspective for developing project interface plans and stakeholder relations, and becomes an important part of the overall team development plan for optimizing team performance throughout the project life cycle.

Time to Develop. The Skill Inventory can be developed in two modes:

Mode I: First-Time Construction. When the Skill Inventory template is constructed for the first time, the specific skill categories and components must be defined for each class of personnel. This includes determining the skill sets for each skill category, evaluating the skill components for importance and capability, plus skill development planning. Time required for developing one Skill Inventory: 3 to 4 hours.

Mode II: Subsequent Applications. This includes fine-tuning of skill sets in the established template and evaluation of the skill components for importance and capability, plus skill development planning. Time required for each Skill Inventory: 2 to 3 hours.

Benefits. The Skill Inventory is an important tool for supporting the organization and development of multifunctional teams. Specifically, the Skill Inventory can be used as a tool for assessing actual skill requirements and proficiencies. For example, a list can be developed, for individuals or teams, to assess the following for each skill component or set:

- Criticality of this skill to effective job performance

- Existing level of proficiency

- Potential for improvement

- Required support systems and managerial help

- Suggested training and development activities

- Periodic reevaluation of proficiency

Therefore, the Skill Inventory is useful in developing professional training programs and training methods. It also provides a framework for the team to identify the conditions necessary and critical for project success and has become an important contemporary tool for project team-building.

Advantages and Disadvantages. Advantages include the following:

- Provides a template for summarizing the skill sets needed for effective teamwork and project success.

- Provides a scorecard for assessing the criticality and capability of skill sets.

- Provides a framework for building the total project team and for managing stakeholder relations.

- Provides a framework for connecting operational resources with business strategy.

- Helps in identifying project stakeholders.

- Creates an environment conducive to team building.

- Leads to organizational learning.

Disadvantages include the following:

- Considerable time and leadership required for constructing initial Skill Inventory template.

- Some time and leadership are required for developing an inventory update.

- Difficulty of standardizing skill sets, criticality, and capability measures.

- Potential for conflict over different perception of skill sets and scoring.

- Misuse of the Skill Inventory for resource and priority negotiations.

Variations. Many variations exist in the structure and application of the Skill Inventory, ranging from the selection of different skill categories to scoring schemes that are more quantitative or more descriptive. Six major variations stand out regarding their applications and will be referenced more specifically.

- Single Skill Inventory. One single Skill Inventory is often used for the entire project organization. This is primarily done for keeping the process simple and for saving tool development time. However, a single inventory also minimizes the risk of “micro-analyzing” skill requirements, instead providing a more integrated, unified picture of what “we as the project team stand for and need to succeed.”

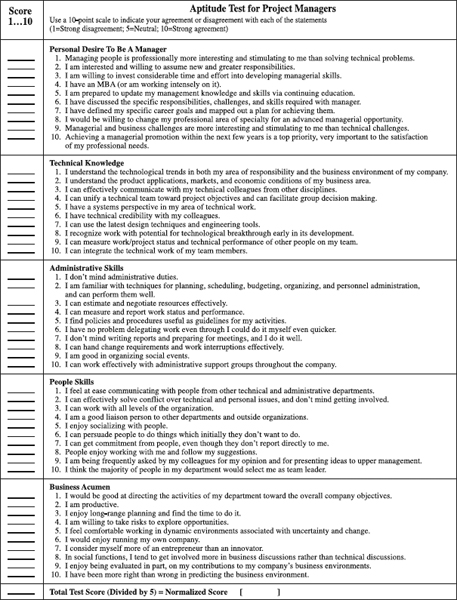

- Aptitude testing. The Skill Inventory format can be applied for team and professional development. The example in Figure 10.8 shows a modified skill inventory, formatted as an Aptitude Test for Project Managers.

- Team readiness. The Skill Inventory format, such as the template shown in Figure 10.6, can be modified for conducting a team readiness test (for specific discussions and formats, see [12, 13]).

- Team performance measures. The Skill Inventory template, such as the template shown in Figure 10.6, can be modified for conducting a team readiness test.

- Post project review. The Skill Inventory format (shown in Figure 10.6) can be modified for conducting postmortem reviews, comparing startup against closeout criticality of skill sets and their developments.

- Project Management Maturity Model. The Skill Inventory can be integrated as part of a broader organization development effort. Templates such as shown in Figure 10.7 can be modified to become part of the Project Management Maturity Model (PM3) and its testing schemes toward PM success (for specific discussions and self-assessment formats see Kerzner [14]).

Customize the Skill Inventory. The template shown in Figure 10.6 provides a good general format and convenient starting point for customizing the Skill Inventory. When the Skill Inventory template is constructed for the first time, the specific skill categories and skill components must be defined for each class of personnel, as previously discussed in the “Constructing a Skilled Inventory” section. Additional customizing can be undertaken by integrating skill sets suggested by stakeholders peripheral to the operational core team, such as customers, contractors, and support groups. However, caution should be exercised not to expand the skill sets beyond 50 items. In the same context, an effort should be made to keep the measurements simple, following the guidelines suggested in the “Constructing” section.

Figure 10.8 Aptitude test for project managers.

Summary

The Skill Inventory is a powerful organization development tool. It helps to identify, recruit, and develop the skills sets needed for bringing together high-performing project teams that can execute projects effectively according to established plans. The Skill Inventory can be customized to provide templates for extended PM developments, such as managerial aptitude testing, team readiness reviews, team performance measures, post project reviews, and PM maturity model assessments. The Skill Inventory offers business leaders a tool for going beyond the obvious and simple methods of developing PM talent. It helps them to recognize the highly multidisciplinary nature of skill requirements and the need for integrating professional skill developments into the business process.

Make sure that the Skill Inventory is properly structured and effectively applied. It should include the following components:

- The structure should list skill components grouped into skill categories.

- The skill components should be customized for the given project situation.

- Skill components should be judged/scored regarding their criticality and current capability.

- Senior project personnel should participate in the development of the inventory and its scoring.

- Skill requirements should not be micro-analyzed.

- The inventory should be used as an information source and catalyst for creating the team development plan.

- Skill Inventory development should involved the total project team, and the final document should be shared with all team members.

- The Skill Inventory application should focus on organizational learning and improvement.

Commitment Scorecard

What Is the Commitment Scorecard?

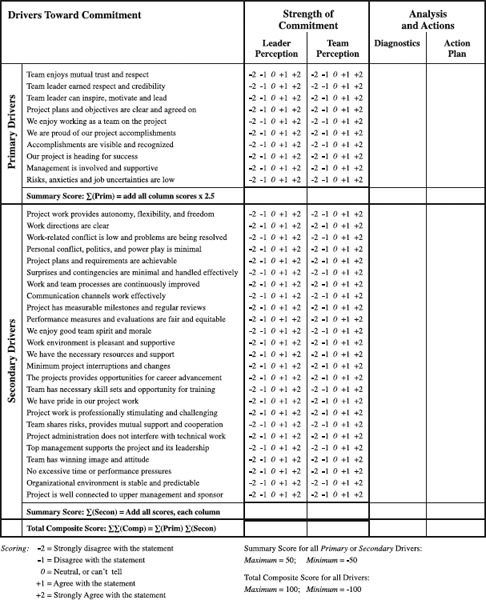

The Commitment Scorecard is a tool for systematically identifying the level of team commitment and buy-in to the project and its established objectives. The Commitment Scorecard is a powerful tool for diagnosing commitment deficiencies and developing stakeholder commitment throughout the project organization. It is especially effective for building commitment during the early stages of team formation and for maintaining commitment over the project life cycle. While virtually all managers recognize the critical importance of commitment for effective teamwork and project performance [15], only one in eight managers feels capable of effectively building and sustaining commitment from the various stakeholders of the project environment [16]. The concept of the scorecard is similar to other performance assessment tools, such as the business scorecard, team scorecard, or project performance scorecard. The specific measurements and their application to project team building were developed by the author, based on extensive field studies over the past ten years [16, 17]. The basic structure of the Commitment Scorecard is shown in Figure 10.9.

Constructing a Commitment Scorecard

As shown in Figure 10.9, the Commitment Scorecard is structured for ready use. It utilizes pretested statements for measuring the level of commitment to a project and its objectives. The statements are divided into 10 primary and 25 secondary, or derivative, drivers, identifying the most common components that support and drive individual, as well as team commitment. For each statement, the scorecard provides space for recording a judgment score of agreement from project stakeholders. The sample scorecard of Figure 10.9 provides two score sections: (1) project leader perception and (2) team perception. The number of columns can be expanded to include additional stakeholders and their judgments. A five-point Likert scale is suggested for scoring the statements, as shown in the following:

−2 = Strongly disagree with the statement

−1 = Disagree with the statement

0 = Neutral or can't tell

+1 = Agree with the statement

+2 = Strongly agree with the statement

Figure 10.9 Commitment scorecard.

Commitment Is a Natural Characteristic of Project Teams and Can Be Developed!

The components that drive commitment do readily exist in many project environments. They are embedded in the project management process, such as planning, tracking, and reporting. The desire for commitment is stimulated by the work, its challenges, visibility, and accomplishments. Yet, this desire must be carefully cultivated, highlighted, and connected to the team's motivation [1]. Understanding the drivers and barriers to commitment, their sources and secondary influences, is an important prerequisite for gaining and maintaining commitment from the team and, hence, for leading project teams effectively toward desired results.

In addition to the judgment of agreement, the Commitment Scorecard provides two columns for (1) analyzing commitment problems and (2) action plans for strengthening commitment and team performance. Since space in the scorecard is limited, these two columns are reserved just for summary statements and references to other documents that articulate the diagnostics and action plans in further detail. The methods of calculating and interpreting commitment score points are discussed in the section that follows.

Preparing Information Inputs. Regardless of its application for assessing individual or team commitment, the first step is completing the questionnaire portion of the scorecard. Next, the summary scores need to be calculated and interpreted as a basis for further discussion, analysis, and development.

Completing the questionnaire. An individual or group judgment should be obtained on each scorecard statement. Especially for the assessment of team commitment, the involvement of task groups or the entire project team in interactive group sessions will produce the most meaningful and realistic results. It also helps to clarify and to build confidence, trust, and respect—factors that ultimately help to strengthen commitment. A simple five-point scale, such as shown in Figure 10.9, is suggested for recording the judgment directly on the scorecard. These scores, together with the composite calculations, become the basis for analysis and action planning. Flip charts, white boards, or Post-it notes are recommended for recording the diagnostics and action plans.

Calculating Commitment Scores. After all statements have been judged, a composite score can be calculated by adding up all individual statement scores. Primary drivers weigh 2.5 times the value of secondary drivers. Specifically, calculate for each column:

- Summary score for all primary drivers. Σ (Prim) = Σ (all absolute primary scores) × 2.5

- Summary score for all secondary drivers.Σ (Secon) = Σ (all absolute secondary scores) × 1.0

- Total composite score for all drivers. Σ (Comp) = Σ (Prim) + Σ (Secon).

Interpreting Commitment Scores. Given the weighting, the judgment scores range between −50 and +50 for both primary and secondary drivers, and between −100 and +100 for the composite score. The following interpretation of the numerical composite score provides a guideline for the established level of commitment:

- Composite scores are negative. Virtually no commitment has been obtained from the people surveyed. Unclear project plans, fear of failure, and lack of incentives and interest are often the reasons for lack of commitment.

- Composite score of 0-50 points. Some commitment has been established, with much room for improvement. The situation is typical for a team that is in the storming stages of development or that has just entered the norming stage.

- Composite score of 51-75 points. This indicates a reasonably strong level of commitment. Yet further improvements via team development should be targeted.

- Composite score above 75 points. This indicates very strong commitment to the project and the team. Only 10 percent of all project teams (15 percent of all project leaders) tested reach this level of commitment. Effective leadership is required to refuel and maintain this high level of commitment.

Communicating the Commitment Scorecard. The Commitment Scorecard should be documented separately from the project plan and shared with the project team and stakeholders in management. The template of Figure 10.9 provides a convenient format for “quantitatively” summarizing the commitment status. A memo-report, together with the tabulated results of Figure 10.7, is suggested for communicating the survey findings, including analysis and recommendations for team development toward unified, committed high project performance. This report, together with its action plan, becomes a roadmap for developing commitment during the early stages of team formation. It also serves as a tool for continuing team development, helping to maintain, refuel, and sustain high levels of commitment.

Utilizing the Commitment Scorecard

When to Use. The Commitment Scorecard is a useful tool for assessing and developing the commitment of a project team and other members of the organization throughout the project life cycle. The tool is especially beneficial during the early stages of project team formation and team planning. It provides a framework for clarifying the issues associated with gaining and maintaining buy-in to established project plans and objectives, and for identifying and removing the barriers that impede individual or team commitment.

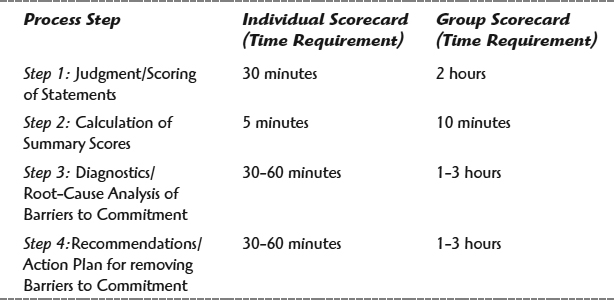

Time to Develop. The Commitment Scorecard development is a four-step process that can be completed by individuals or in groups:

Benefits. The Commitment Scorecard facilitates the systematic identification of commitment by individuals and teams to the project and its established objectives. It provides a framework for diagnosing commitment deficiencies and developing commitment throughout the project organization. The Commitment Scorecard also helps in unifying the team behind the project goals and objectives, and helps to focus the organization on the conditions critical for project success, hence providing a bridging mechanism between the operational focus of the project environment and the strategic focus of the business enterprise. In addition, the Commitment Scorecard provides perspective for developing project interfaces and stakeholder relations, and becomes an important part of the overall team development plan for optimizing team performance throughout the project life cycle. In summary, the Commitment Scorecard provides

- Insight into to drivers and barriers toward commitments

- A framework for project stakeholders identification

- Quantitative measures of commitment

- A framework for systematically diagnosing deficiencies and developing commitment

- An opportunity for benchmarking and organizational learning

- Measures for the Project Management Maturity Model

- A focus on strategic goals and organizational objectives

- Perspective for developing project interfaces and stakeholder relations.

Advantages and Disadvantages. Advantages include the following:

- Provides a scorecard for assessing strength of commitment, including all of the above benefits.

- Provides a template for summarizing commitment analysis and development plan.

- Offers a low-cost and low-risk organization development process.

- Helps in identifying project interfaces and stakeholders.

- Creates an environment conducive to team building.

- Leads to organizational learning.

Disadvantages include the following:

- Time and considerable leadership is required for applying scoreboard to project team development.

- Standardized statements don't fit all project situations; a need for customization often exists.

- Potential for conflict over different perception of statements and scoring.

- Inability to solve all commitment problems with a scorecard.

Leadership Implications

Project leaders must understand the criteria and organizational dynamics that drive people toward commitment. Building commitment requires a leadership style that relies to a large degree on shared power and earned authority. An effective team leader is a social architect who understands the interaction of organizational and behavioral variables and can foster a can-do climate that is high on active participation and professionally stimulating interactions but low on anxieties and dysfunctional conflict. This requires skills in leadership, administration, organization, and technical expertise. It further requires the project leader's ability to involve top management and to build alliances with support organizations, ensuring organizational visibility, resource availability, and overall project support throughout its life cycle. These are some of the important criteria for gaining and sustaining commitment with project teams and other stakeholders of the project environment.

Recommendations for Obtaining and Sustaining Commitment

Despite the complexities of the commitment process and the differences among companies, certain characteristics of leadership and work environment appear to be most favorably associated with obtaining and maintaining commitment in team-based organizations. These conditions serve as bridging mechanisms for overcoming fears and anxieties that are normal and predictable when commitment is requested from an individual or project team. Some recommendations are discussed with focus on three categories; people-oriented influences; organizational process, tools, and techniques; and work- and task-related influences.

People-Oriented Influences. Factors that satisfy professional interests and needs seem to have the strongest effect on the ability to obtain commitment and eventually sustain commitment over the project life cycle. The most significant drivers are derived from the work itself, including personal interest, pride an d satisfaction with the work, professional work challenge, accomplishments and recognition, as well as the trust, respect, and credibility placed in the team leader. Other important influences include effective communications among team members and support units across organizational lines, good team spirit, mutual trust, low interpersonal conflict, and personal prides, plus opportunities for career development advancement and to some degree, job security. All of these factors help in building a unified project team that can leverage the organizational strengths and core competencies effectively. These are the factors that seem to create an environment conducive to team commitment and uitimately high project performance.

Organizational Process, Tools, and Techniques. These influences include the organizational structure and technology transfer process that relies on modern project management techniques. Field research specifically points at effective project planning and support systems, clear communication, organizational goals and project objectives, and overall managerial leadership as important conditions for effectively gaining and sustaining commitment. An effective project management system also includes effective cross-functional support, joint reviews and performance appraisals, and the availability of the necessary resources, skills and facilities. Other crucial components that affect the organizational process, and ultimately commitment, are team structure, managerial power and its sharing among the team members and organizational units, autonomy and freedom, and most importantly, technical direction and leadership. Many of the variables related to organizational process are primarily under the control of senior management. They are often a derivative of the company's business strategy developed by top management. It is important for management to recognize that these variables affect the team's perception of the work environment, such as organizational stability, availability of resources, management involvement and support, personal rewards, organizational goals, objectives, and priorities, and they therefore have a direct effect on commitment.

Work- and Task-Related Influences. Commitment also has its locus in the work itself. Variables associated with the personal aspects of work, such as interest in the project, ability to solve problems, minimize risks and uncertainties, job skills, and experience, are significant in driving commitment. Hence, it is important for management to understand the personal and professional needs and wants of their team members and to foster an organizational environment conducive to these needs. Proper communication of organizational vision and perspective is especially important. The relationship of managers to staff and people in their organizations, mutual trust, respect, and credibility all are critical factors toward building an effective partnership between the project team and its management and sponsor organization.

Taken together, project leaders must be able to attract and hold people with the right skill sets, appropriate for the work to be performed. Managers must invest in maintaining and upgrading job skill and support systems, and promote a project climate of high interest and involvement, in order to influence the commitment process favorably.

Make sure that Commitment Scorecard is properly structured and effectively applied:

- The set of questions and their weights, as shown in Figure 10.7, should be considered as a “standard,” and modified only as an exception, not a rule.

- The questionnaire should contain statements in two groups: primary and secondary drivers to commitment, each with different weights.

- Each survey instrument should contain only one score column to avoid confusion and bias.

- Each question should be carefully judged/scored after thoughtfully considering the question in the context of the given project situation.

- The survey findings, including analysis and recommendations, should be summarized in a standardized format.

- The scorecard survey results should be shared with all project team members.

- The scorecard survey results should be used as a roadmap and catalyst for continuing team development and organizational learning throughout the project life cycle.

Customize the Commitment Scorecard. The template shown in Figure 10.9 provides a good general-purpose format of the Commitment Scorecard. Customization of the questionnaire statements is recommended only after careful consideration, because the questionnaire and score weights suggested in Figure 10.9, are based on extensive field research (e.g., the statements explain over 70 percent of the variance of commitment in project teams; [16]). The probability of covering a larger spectrum of commitment variables with substitute statements is low. However, if the scoreboard user is willing to invest more time in the generation of the score-board, a larger set of statements will likely cover more commitment variables and provide further insight into the drivers and barriers of commitment for a given situation. In a different context, two suggestions for customization are being made. First, the scoreboard that is given to an individual or team as survey instrument should contain only one score column (that is the column with the numbers) to avoid confusion and bias. The summary board can contain all columns of all parties surveyed or just their composite scores. Second, the format of the memo-report, which summarizes the survey findings and includes analysis and recommendations for team development, should be specified regarding its structure, contents, and length. Such report standardization will benefit benchmarking and management actions, along with the overhead required for team development effort.

Taken together, the effective use of the Commitment Scorecard involves many organizational and managerial issues with considerable leadership implications, as summarized in the Text Sidebar. Part of these challenges involve the proper understanding of the criteria and organizational dynamics that drive commitment, and the managerial skills of negotiating commitments that align project requirements with the professional and personal needs of the team members. Specific recommendations for obtaining and sustaining commitment are summarized in the final Text Sidebar of this section.

Summary

The Commitment Scorecard is a powerful tool for assessing and developing commitment of a project team and other members of the organization. While most frequently applied during the early stages of project team formation and team planning, the scorecard is a useful and effective organization development (OD) tool for developing and sustaining commitment throughout the project life cycle.

Concluding Remarks

Four tools were covered in this chapter: Four-Stage Model of Team Building, Stakeholder Matrix, Skill Inventory, and Commitment Scorecard. All four tools support team planning, the process of identifying, organizing, and developing project teams.

Effective teamwork is a critical determinant of project success and the organization's ability to learn from its experiences and position itself for future growth. To be effective in organizing and directing a project team, the leader must not only recognize the potential barriers to high team performance work but also know when in the life cycle of the project they are most likely to occur. Effective project leaders take preventive actions early in the project life cycle and foster a work environment that is conducive to team building as an ongoing process.

The Four-Stage Model of Team Building provides an effective framework for team formation and development. It also provides an umbrella for integrating many of the tools and concepts that support team planning via customer relations management, skill building, interface management, and commitment. Building effective project teams involves the whole spectrum of management skills and company resources. Most importantly, managers must pay attention to human side. They must understand the complex interaction of organizational and behavioral variables. Through the interaction with all stakeholders, managers can gain insight into the critical functions and cultures that drive project performance and can identify those components that could be further optimized. Effective project leaders are social architects who understand the interaction of organizational and behavioral variables and can foster a climate of active participation and minimal dysfunctional conflict. They also build alliances with support organizations and upper management to ensure organizational visibility, priority, resource availability, and overall support for the multifunctional activities of the project throughout its life cycle. The tools presented in this chapter should help in the process of team planning and proactively facilitating control of the project startup process.

A Summary Comparison of Team Planning Tools

References

1. Burgess, R. and S. Turner. 2000. “Seven Key Features for Creating and Sustaining Commitment.” International Journal of Project Management 18(4): 225–233.

2. Tuchman, B.W. and M. C. Jensen. 1977. “Stages of Small Group Development Revisited.” Groups and Organizational Studies 2: 419–427.

3. Hershey, P. and K. Blanchard. Organization and Behavior. 1995, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

4. Olson, E.M., et al. 2001. “Patterns of Cooperation during New Product Development among Marketing, Operations and R&D.” Journal of New Product Development 18(4): 258–271.

5. Keller, R. 2001. Cross-Functional Project Groups in Research and New Product Development. Academy of Management Journal 44(3): 547–556.

6. Zien, K. A. and S. A. Buckler. 1997. “From Experience: How Canon and Sony Drive Product Innovation.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 14(4): 274–287.

7. Cohen, A. R. and D. L. Bradford. 1990. Influence without Authority. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

8. Tuman, J. 1993. “Models for Achieving Project Success through Team Building and Stakeholder Management” The AMA Handbook of Project Management. Edited by P. Dinsmore. New York: AMACOM.

9. Gray, C. and E. Larson. 2000. Project Management. New York: Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

10. Shenhar, A. and H. J. Thamhain. 1994. “A New Mixture of Project Management Skills.” Human Resource Management Journal. 13(1): 27–40.

11. Shuman, J. and H. J. Thamhain. 1996. “Developing Technology Managers” Chapter 21 in Handbook of Technology Management. Edited by G.H. Gaynor. New York: McGraw-Hill.

12. Wellins, R. S., W. C. Byham, and J. M. Wilson. 1991. Empowered Teams. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

13. Robins, H. and M. Finley. 2000. Why Teams Don't Work. San Francisco: Berrett-Kohler.

14. Kerzner, H. 2001. The Project Management Maturity Model. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

15. Berman, S., et al. 1999. “Does Stakeholder Orientation Matter? The Relationship between Stakeholder Management Models and Firm Financial Performance.” Academy of Management Journal 42(5): 488–506.

16. Thamhain, H. J. 2002. “Building Project Team Commitment” at PMI-2002 Conference. San Antonio, Tx.

17. Thamhain, H. J. and D. L. Wilemon. 1999. “Building Effective Teams for Complex Project Environments.” Technology Management 5(2): 203–212.