16

Selecting and Customizmg Project Management Toolbox

You are unique, and if that is not fulfilled then something has been lost.

Martha Graham

Which of All These Tools Do You Really Need?

Now that we finished our review of 50+ project management tools in the previous chapters, a natural question comes to mind: “Which of all these tools and in which form do I really need?” The goal of this chapter is to answer this question by developing a framework for selecting and adapting a project management toolbox that supports the SPM process that we discussed in Chapter 1. Specifically, the framework should help customize the use of the toolbox while accounting for the specific situation of various companies and projects.

Process for Selecting and Adapting Project Management Toolbox

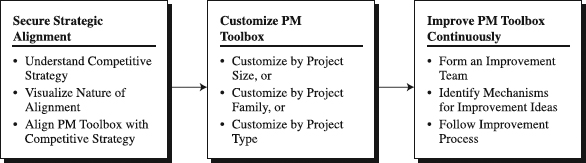

There are three major steps, each including several tasks, in selecting and adapting a project management toolbox for specific projects (see Figure 16.1):

- Secure strategic alignment

- Customize the project management toolbox

- Improve continuously

Aligning the project management toolbox with the organization's competitive strategy tells us in broad terms what categories of project management tools to select and adapt. This alignment drives the next step—customization of the project management toolbox by selecting specific project management tools. The deployment of the project management toolbox in real-world projects will reveal its glitches and generate new learning, resulting in a need for the toolbox's continuous improvement, the third step. Details about each step follow.

Figure 16.1 Process for selecting and adapting a project management toolbox.

Secure Strategic Alignment

The purpose of the project management toolbox is to enable the implementation of projects that will effectively support an organization in pursuing its competitive strategy and goals. To make the purpose happen, you need to fully align the project management toolbox with the competitive strategy. This can be achieved through the following steps:

- Understand the organization's competitive strategy.

- Visualize the nature of alignment.

- Align the project management toolbox with the organization's competitive strategy.

Understand the Organization's Competitive Strategy. In Chapter 1 we showed that an organization's project management toolbox has to be aligned with its competitive strategy. To be successful in designing the toolbox, therefore, project managers must understand the strategy. However, many of them do not. Why? Among many reasons for this, two matter here. First, in many organizations, strategy formulation and implementation is viewed as the executives' domain of work—they are tasked to chart a competitive strategy course in an organization—to which mere mortals such as project managers have no access. Second, because of such a view many project managers do not show or show a very little interest in learning about the competitive strategy. As a result, neither is the strategy communicated to project managers nor do they work to understand it. Project managers should be tenacious, probing and digging to comprehend the strategy, even if the strategy is not communicated.

These two reasons create substantial obstacles for project managers. To remove the obstacles, project managers need to talk to senior managers and convince them that competitive strategy is the guide to planning and implementing projects, the SPM process, and the project management toolbox, and that project managers need to know it in order to secure expected returns on their projects Therefore, our mandate is clear: Understand the strategy or designing the toolbox will be like shooting in the fog—we neither know where the target is nor whether we hit it.

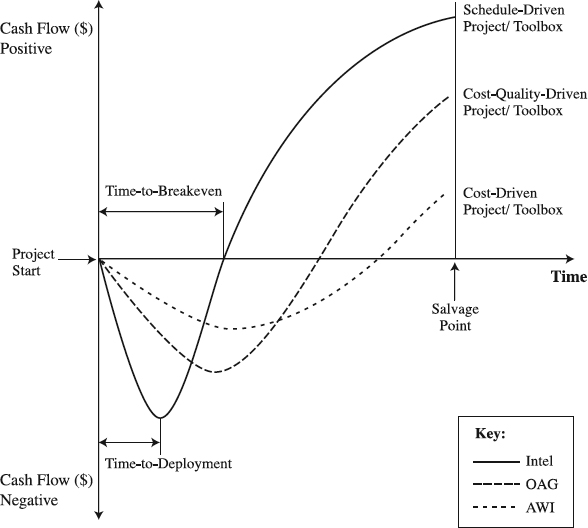

Visualize the Nature of Alignment. Part of convincing the senior managers is the ability to clearly visualize the nature of the alignment between the toolbox and the competitive strategy. In Chapter 1 we laid the foundation for the alignment. In particular, we used examples of three companies—Intel, AWI, and OAG—to illustrate how the project management toolbox can be focused to support competitive strategies. To support its differentiation strategy, Intel pursues a schedule-driven toolbox. A cost-focus toolbox is what AWI does to back its cost leadership competitive strategy. OAG uses cost-quality focus in its toolbox to sustain its competitive strategy of best cost. Obviously, the focus in each company's toolbox is aligned with their competitive strategy. This is summarized in Figure 16.2.

To keep our focus pragmatic, we will illustrate how these examples of the project management toolbox work in real-world projects. For that purpose, in Figure 16.3 we show what we conveniently call investment curves—a more precise term is the Net Present Value curves—for three comparable projects performed in tune with the competitive strategies of Intel, AWI, and OAG. Each curve shows four important points: project start, time-to-deployment (TTD), time-to-breakeven (TTB), and salvage point. Project start is the time when the project is launched and begins to spend resources; therefore, the cash flow becomes negative. Investment and negative cash flow continue to increase until the project is completed. At that time the project product can be deployed, or in other words used by customers. Instead of TTD, project managers in product and software development use the term time to market. Most of other project managers prefer the term project cycle time or, simply, project completion time. Note that negative cash flow usually reaches its peak at the TTD point. After that, the use of the project product begins to generate the returns, and as a result, the curve turns up until it reaches TTB. This is the point where all investments in the project are equal to returns generated by the use of the project product. Beyond that point, the cash flow turns positive and typically continues to do so until the project product is salvaged.

Figure 16.2 Examples of the alignment of project management toolbox with competitive strategies.

Figure 16.3 Each project curve uses different project management toolbox.

We will use the curves to explain the nature of the project management toolbox's alignment with the competitive strategy for each of the three companies. Consider, for example, Intel's case. One element of Intel's differentiation strategy is speed in projects. Figure 16.3 illustrates that point; TTD and TTB in Intel's curve are reached much sooner than for other two companies. For this to be possible, Intel needs to use a schedule-driven toolbox in which the central role and priority belong to tools that can help accomplish as fast TTD and TTB as possible. These are schedule planning and control tools that set the tone for company's projects—Gantt Chart, Time-scaled Arrow Diagrams, CPM Diagrams, Milestone Chart, and so on. Simply, most of the management time and attention goes to these tools, and they also serve as the primary basis in crunch times of making key decisions. This does not mean that other components of the typical project management toolbox such as cost and quality tools are ignored. Quite to the contrary, they are important and have their role in the toolbox. That importance and role are dictated by the importance and role of cost and quality goals in Intel's competitive strategy. Obviously, Intel cares about building quality products to keep customers happy and uses Control Charts, Flowcharts, and Affinity Diagrams for that purpose. In efforts to keep cost goals as low as possible, Intel deploys Cost Estimates and Baselines.

But in Intel's hierarchy of goals, quality and cost goals are lower than schedule goals. That is why Intel's curve has more negative cash flow at TTD than the other two curves; speed, apparently, has its cost [1]. As a result, the driving force of project management toolbox are schedule tools. Quality, cost, and other tools are subjugated to schedule tools.

The case is different in the toolbox of AWI, a company bent on cost leadership. Logically, then, its projects are cost-driven, searching to minimize project cost whenever possible. This logic is apparent in Figure 16.3. The AWI curve has a lower point of the most negative cash flow than those of Intel or OAG. Not by accident! It is the intended goal and realized outcome of project actions. To accomplish such project goals, AWI is willing to take the longest time to reach TTD and TTB. Crucial in this effort is a cost-driven toolbox. Its emphasis is on cost, cost, and cost. Correspondingly, cost estimates and cost baselines are carefully prepared, as is the assessment of return on investment, even for small cost-cutting projects. Obviously, the primary attention and management time are devoted to cost planning and control tools in order to lower the cost and sustain AWI's strategy of cost leadership. Even schedule and quality tools are adapted to support the low cost goals. Gantt Charts, known for their simplicity and low cost of development, are the schedule tools of choice, shooting for project durations that offer the lowest cost of project execution. CPM Diagrams, which take time and, hence, cost to train people and prepare are used infrequently, primarily in large projects. Control Charts, Flowcharts, and other quality tools are focused on making the project management process fully standardized and built on templates for each tool from WBS to Cost Estimate to Risk Response Plan. Other tools are applied with the same low cost reasoning. Risk Response Plan is focused on cost risks. Meeting agendas are standardized to lessen the cost of meetings. A similar approach is with the WBS development—stick with the minimum number of levels that enable cost-effective management.

The intent of aligning the project management toolbox with the competitive strategy is aggressively pursued in OAG as well. The driving force is the best-cost strategy that is also translated to the project level. As can be seen from Figure 16.3, TTD and TTB are shorter than AWI's but longer than Intel's. This means that cost focus is lower than AWI's but higher than Intel's. Such cost philosophy is closely intertwined with the need for the project to emphasize quality goals more than the other two companies. Given this situation, how does one shape a quality-cost driven project management toolbox?

A combination of well-balanced quality and cost tools has the priority. It is so much so that management pays the highest attention to them, giving them most of their time and relying on them for major decision making. Formal or informal customer voice tools and quality control programs are crucial for hitting the customer-set quality level, as are Cost Estimates and Baselines. Schedule tools, generally simpler and less costly such as Gantt Charts, are part of the game. To OAG and its customers, delivery on schedules matters, because keeping customers is not possible without being punctual. Nevertheless, schedule goals are not overly ambitious, resulting in not so fast schedules. Clearly, in OAG's food chain of project goals, schedule tools are on the lower level than the quality-cost combination. Other tools such as scope or risk tools are also adapted to support the combination. For example, it is usual to prepare the Risk Response Plan focused on cost, rather than on schedule (as a schedule-driven toolbox would stress).

As you can see from our discussion, the nature of alignment of the toolbox is reflected in the balance of two issues. First, most of the tool types show up in all three toolboxes. Obviously, this is where the one-size-fits-all approach makes sense. The second issue concerns the situational approach, adapting tools to account for the character of the three toolboxes. With this knowledge in mind, we are now ready to offer a few guidelines for the alignment of the toolbox.

Align the Project Management Toolbox with the Organization's Competitive Strategy. Four tasks are important in achieving the alignment:

- Set the desired level of the alignment.

- Establish the current level of the alignment.

- Identify gaps between the current and desired alignment.

- Act to provide the desired alignment.

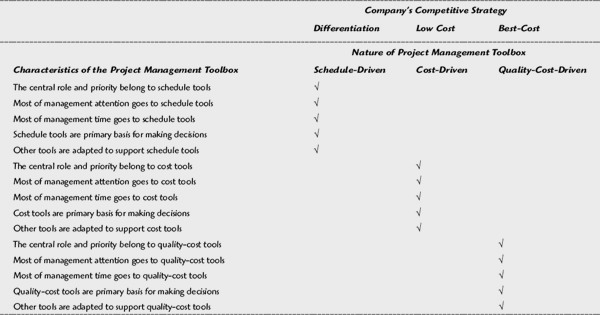

In many companies, the process team responsible to manage the project management process (or specially appointed teams) sets the desired level of the toolbox alignment. For example, refer to Table 16.1. This table identifies the characteristics that each of the three types of the project management toolbox—schedule driven, cost driven, and quality-cost driven—should have. Earlier in this section, we described the nature of these characteristics in examples of Intel, AWI, and OAG.

In setting the desired level, the team may decide to go for an incremental implementation of the schedule-driven toolbox. Accordingly, they can choose to give simple schedule tools the central role and priority, while leaving the adaptation of other tools (e.g., cost or risk planning tools) to support schedule tools for some later time.

If the process team understands the issue of the alignment, the path is clear. Lots of discussion may be needed to build a consensus about the level, especially if many of the involved people who have a say are busy. Good planning, leadership, and communication will certainly help in accomplishing the task. Add to this good change management skills and endless patience, when there is a need to first educate the process team about the alignment substance.

Table 16.1: Characteristics of the Strategically Aligned PM Toolboxes

Interviewing project customers, managers, and sponsors is very helpful in obtaining information about the current level of the alignment. Observing and auditing key projects will further improve the knowledge of the actual alignment. Skipping these tasks and assuming that we know where the current notch for the alignment is may result in serious problems.

Once the desired and current levels of alignment have been known, the time has come to clearly identify the gaps between them. The significance of the gaps—whether they are major or minor—will be a basis for the decision to what extent the gaps will be acted on and closed.

In this section we explained how to go about securing strategic alignment of the toolbox. Necessary for this are understanding of the organization's competitive strategy, visualizing the nature of the alignment, and performing the alignment. Note that the alignment act is truly strategic. It provides a broad strategic direction for the toolbox customization of a coarse granularity. To use the toolbox in real-world projects, you need to customize the toolbox with fine granularity. That is the focus of our next step.

Customizing the Project Management Toolbox

There are multiple options for customizing a strategically aligned project management toolbox. Three of them are perhaps the most viable:

- Customization by project size

- Customization by project family

- Customization by project type

The three options are three different ways to select and adapt the toolbox. Each option has the purpose of showing which specific project management tools to select and adapt for the project management toolbox. For this to be possible, each option is based on the SPM process, which actually dictates the choice of the tools. As discussed in Chapter 1, each tool in the toolbox is chosen to support specific managerial deliverables in the SPM process. Also, the PM toolbox is constructed to include all tools necessary to complete the whole set of the SPM process's managerial deliverables. Therefore, in any of the options the first step is to lay down the SPM process—that is, its phases, project management activities, and managerial deliverables (technical activities and deliverables are beyond the scope of the book). Then comes the selection of individual tools to support the deliverables.

An in-depth knowledge of individual tools is a prerequisite to each of the options, because you need to understand how each tool can support a managerial deliverable. We will describe the options in turn and offer guidelines for selecting one of them for the implementation. Whichever option has been chosen, for those who select individual project management tools or design toolboxes relying on A Guide for Project Management Body of Knowledge (popularly called PMBOK), Appendix A provides linking of the tools covered in this book to PMBOK.

Customization by Project Size. Some organizations use project size as the key variable when customizing a project management toolbox that is already strategically aligned. Their view is that larger projects are more complex than smaller ones. Or, the size is the measure of the SPM process complexity. The reasoning here is that as the project size increases, so does the number of project management activities and resulting managerial deliverables in a project, and so does the number of interactions among them. Worst of all, this number of interactions grows by compounding, rather than linearly [3]. Such increased complexity, then, has its penalty—larger projects require more managerial work and deliverables to coordinate the increased number of interactions. This translates into SPM processes and project management toolboxes for larger projects.

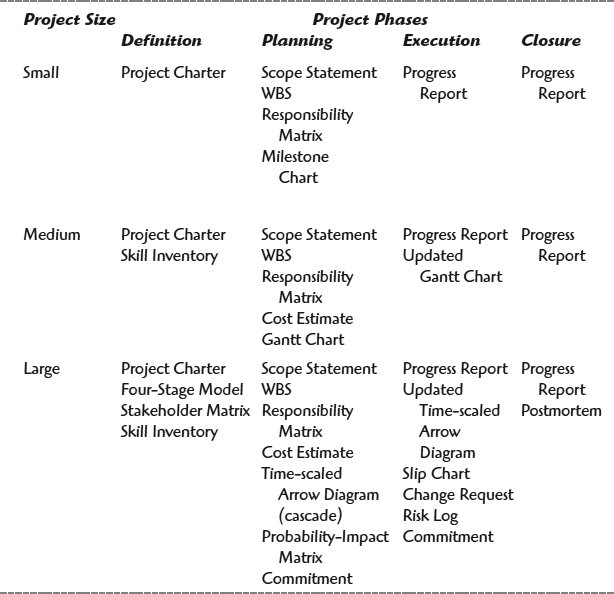

Since different project sizes require different SPM process and project management toolboxes, we first need a way to classify projects by size and then customize their toolboxes. For size classification we will draw on the experience of some companies. In Table 16.2 we present three examples. All companies created three classes of project size: small, medium, and large. The units to measure the size are dollars or person-hour budgets. On the basis of the size, the companies determined the managerial complexity of its project classes and SPM processes. The complexity, further, dictated the project management toolbox, a simplified example of which is illustrated in Table 16.3 (for more examples, see Appendix B). For the sake of simplicity, only the toolbox is shown, leaving out technical deliverables.

As Table 16.3 indicates, some of the tools in the toolboxes for projects of different size are the same, others different. For example, all use the Progress Report because all projects need to report on their performance. Since managerial complexity of the three project classes and their SPM processes call for different tools, some of the tools differ. A Risk Log, for example, is needed only in large projects. To be successful, the process team designing the toolbox should carefully balance the one-size-fits-all tools with those that account for the specific situation of the SPM process.

Table 16.2: Examples of Project Classification per Size in Three Companies

Experience of these companies offers several guidelines for customizing the project management toolbox by project size:

- Identify few classes of projects and their SPM processes.

- Define each class by the size parameter.

- Match the class complexity with the proper toolbox, each tool supporting a specific managerial deliverable.

Note that while customization by project size offers advantages of simplicity, it also carries a risk of being generic, disregarding other situational (contingency) variables. To some, these other variables may be of vital importance, as will be pointed in the next section on customization by project family.

Customization by Project Family. When the project management toolbox is strategically aligned, you can opt to customize it by family types in their industry. Many companies choose such options in a belief that project families in their industry are sufficiently unique to merit a family-industry-specific SPM process and toolbox [4]. Such an approach can be easily understood with the help from the situational (contingency) view [2].

Table 16.3: Example of Customization of PM Toolbox by Project Size

As a group of organizations that compete directly with each other to win in the marketplace [5], an industry is characterized by the nature of its environment and business task. For example, companies in a high-technology industry face an environment of dynamic technology change. Because of this, their business task abounds with fast time-to-market projects [6]. Combined, the described nature of environment and business task work to create similar challenges in families of projects. For example, a project family of new product development projects in high-tech industries faces similar challenges. So do facilities management projects, manufacturing projects, marketing projects, and information technology projects in the high-tech industry. These same project families also exhibit similarities in other industries.

A resulting phenomenon is, then, that SPM processes and related project management toolboxes to resolve the challenges of a project family in a certain industry tend to converge. This creates a situation in which several essentially similar models of the SPM process and toolbox are perceived as dominant family-industry standards. In response, some companies tend to select toolboxes per family-industry standards, typically exploiting the opportunity of benchmarking these dominant models. One of such models was illustrated in Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1.

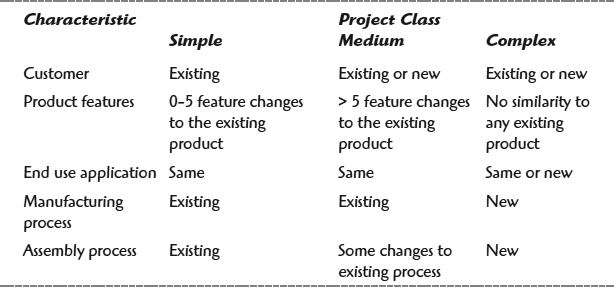

Many organizations take this customization by project family-industry standards further. In particular, they recognize that each family has multiple project classes of different technical novelty, each calling for a customization of the toolbox. Consider, for example, the case of a low-tech manufacturer (Table 16.4).

This company classifies all projects of its new product introduction project family into three groups: simple, medium, and complex. To distinguish them, the company uses 11 characteristics, mostly related to the project technical novelty. Some of them include customer, product features, end use application, manufacturing process, and assembly process.

Table 16.4: Example of Classifying Projects in a Project Family by Technical Novelty

Generally, the more highly technical the novelty, the more complex the projects are [7]. This is because the increasing technical novelty in projects leads to more uncertainty, elevating the need for more flexibility in the SPM process and supporting toolbox. In particular, as the technical novelty of projects increases, the SPM process

- Takes more iterations and time to define the project scope.

- Requires higher technical and managerial skills.

- Deepens communication.

- Calls for more effective management of change.

Adapting to such SPM process, you also need to adapt the project management toolbox. As technical novelty grows

- The more evolving the Scope Statement and WBS are.

- The Gantt Chart or CPM Diagram become more fluid, often updated to account for scope changes.

- The Cost Estimates are as fluid as the schedules are.

- The risks increase.

A simple example reflecting these trends in adapting the toolbox for the three classes of new product introduction project family from Table 16.4 is illustrated in Table 16.5 (for more examples, see Appendix C).

As the table shows, the toolboxes of the three classes of projects are similar in some and different in other aspects. For example, all use schedules and Progress Report, clearly an offshoot of the one-size-fits all approach. Still, the schedules differ in that simple projects rely on a simple Milestone Chart, while complex projects use a rolling wave type of the Time-scaled Arrow Diagram. Obviously, the variation in the technical novelty of the project is the source of the differences.

In customizing by family type, you need to be aware of certain advantages and risks. The advantages include the following:

- Simplicity. Because it is built on one variable (technical novelty), this customization type is simple.

- Easy to understand. This customization relies on the technical aspects of projects, the center of the professional background of project managers. Obviously, this makes the customization easy for project managers.

This customization also creates risks in the following:

- Projects light on technology. In these projects, technical novelty is not a relevant issue, rendering the customization irrelevant.

- Introducing too many models. The application of the customization in a company with multiple project families generates as many project management toolboxes, reducing the ability to integrate the families into a coherent company system.

In summary, here are several deployment guidelines when customizing a project management toolbox by project family:

- Classify your projects and their SPM processes into few classes.

- Define each class with a few technical parameters.

- Support each class with the proper toolbox, each tool backing a specific managerial deliverable.

Table 16.5: Example of Customization of PM Toolbox in Project Family Type by Technical Novelty

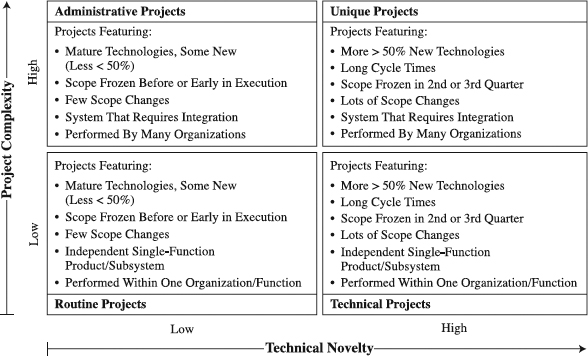

Customization by Project Type. While the previous two options of customization rely on one dimension (variable) each—project complexity (measured by size) and technical novelty, respectively—customization by the project type uses both of the variables, once the toolbox is strategically aligned. We call such a two-dimensional model by the name of its creator—the Shenhar's model [8]. To make it more pragmatic, we will simplify the model, while maintaining its comprehensive nature. Three steps will be used to describe the model:

- Define project types.

- Describe how the two dimensions impact the SPM process of the project types.

- Describe the project management toolbox for the four project types.

Each of the two dimensions includes two levels:

- Technical novelty (levels: low, high)

- Project complexity (levels: low, high). Note that here we use the system scope (very similar to project size) as the measure of project complexity.

This helps create a two-by-two matrix that features four major types of projects (see Figure 16.4):

- Routine

- Administrative

- Technical

- Unique

Figure 16.4 Four types of projects.

Reprinted by permission, Shenhar, J. Aaron, “One Size Does Not Fit All Projects: Exploring Classical Contingency Domains,” Management Sci. 47(3) 394-414, 2001. Copyright (c) 2001, The Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS), 901 Elkridge Landing Road, Suite 400, Linthicum, Maryland 21090-2909, USA.

Routine projects have a low level of technical novelty and assembly type of system scope. At the time of project initiation, these projects mostly use the existing or mature technologies or adapt the familiar ones. Sometimes, some new technology or feature may be used, but not to exceed more than 50 percent of the total number of technologies used. Because of the known technologies, scope is frozen before or early in the execution phase, and few scope changes may occur. Essentially, these are low- to medium-tech projects. The system scope—the assembly type—means that the project can produce a product that is a subsystem of a larger system or a standalone product capable of performing a single function. Typically, the project is performed within a single organization or organizational function (e.g., engineering or marketing function) [8]. Because it takes the routine to deal with the existing technologies and modest scope, we dubbed these projects routine. Examples include the following:

- Continuous improvement project in a department

- Upgrading an existing software package or existing product

- Adding a swimming pool to an existing hotel

- Developing a new model of the traditional toaster

- Expanding an established manufacturing line

Administrative projects are similar to routine projects in terms of the technical novelty—they are low- to mid-tech. Therefore, these projects also use less than 50 percent of new technologies, enjoy an early scope freeze, and have the benefit of few scope changes. However, they differ in the system scope domain. Unlike the routine projects, they produce project products consisting of a collection of interactive subsystems (assemblies) that are capable of performing a wide range of functions [9]. As a result, many organizations or organizational functions are involved, generating a strong need for the integration of both the subsystems and organizations. Such integration will call for more administrative work, which is why we termed these projects administrative. Some examples are as follows:

- Corporate-wide organizational restructuring

- Deploying a standard information system for a geographically dispersed organization

- Building a traditional manufacturing plant

- Developing a new automobile model

- Upgrading a new computer or upgrading a software suite.

The major property of technical projects is their technical content, hence, their name. In particular, more than 50 percent of the technologies that these projects use are new or not developed at the project initiation time. This naturally makes them high-tech and tends to create a lot of uncertainty, requiring long project cycle times. Because of the challenging nature of new technology deployment or development, scope often changes and is typically frozen in the second or third quarter of the project implementation period. Like routine projects, the technical projects build single-function independent products or subsystems of larger systems. For this reason, they are of a low complexity level, calling for a single organization to execute the project. Here are some examples:

- Reengineering a new product development process in an organization

- Developing a new software program

- Adding a line with the latest manufacturing technology to a semiconductor fab

- Developing a new model of computer

- Developing a new model of a computer game.

Like technical projects, unique projects feature high-technology content. What makes them unique is that they push to the extreme on both system complexity and technological uncertainty. More than 50 percent of their technologies are new or nonexistent at the time of the project start. This level of uncertainty, combined with high system complexity, is destined to prolong project cycle times and cause a lot of scope changes. Adding to this challenge is the need for integration of the multiple uncertain technologies. In such an environment, normally the scope would freeze in the second or third quarter of the project cycle time. Further complications are instigated by the involvement of many performing organizations that also need to be managerially integrated. Among such projects:

- Building a city's transportation system

- Developing a new generation of microprocessors

- Building a new software suite

- Constructing the latest technology semiconductor fab

- Developing a platform product in an internationally dispersed corporation.

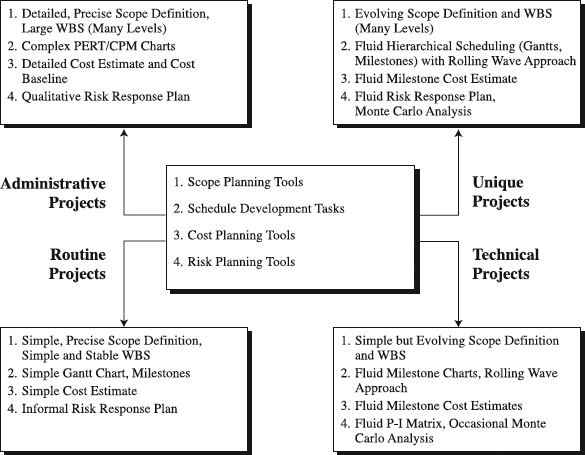

Now that we have defined the four project types, we can move on to the next step—describe how the two dimensions impact the SPM process of these project types. Taken overall, the growing technical novelty in projects generates more uncertainty, which consequently requires more flexibility in the SPM process. As a result, the SPM process [9]

- Takes more cycles and time to define and freeze the project scope

- Needs to make use of more technical skills

- Intensifies communication

- Requires more tolerance toward change

System scope as a measure of the project complexity also has a unique impact on the SPM process. In summary, an increasing system scope leads to an increased level of administration, requiring the SPM process to feature [9]

- More planning and tighter control

- More subcontracting

- More bureaucracy

- More documentation

To support these features of the SPM process, you need to adapt the project management toolbox accordingly. In Figure 16.5 we show examples of several project management tools that have to be adapted to account for different SPM processes in these four types of projects. Detailed explanations about how these tools differ are provided in Appendix D, along with more examples of toolboxes for the four project types.

A summary comparison of the tools for the four project types reveals that they use very similar types of the tools. For example, all use WBS. Still, when the same type of tool is used, there are differences in their structure and the manner how they are used. Consider, for example, Gantt and Milestone Charts. Both are used in the routine and unique projects, but terms of use are significantly different. This is the situational approach—as the nature of the SPM process changes, so does the project management toolbox. In other words, there may be as many toolboxes as SPM processes and the project types they support (we simplified this to four project types, SPM processes, and toolboxes).

Figure 16.5 Customizing project management toolbox by the project type.

Customization of the toolbox by the project type has its advantages and risks. The advantages are that this customization approach is

- Sufficiently comprehensive. It includes two dimensions that account for major sources of contingencies.

- Unifying. This approach may be used for the large majority of projects, providing a unifying framework for all projects in an organization.

Risks from using the approach of customizing the toolbox by the project type need to be recognized as well:

- Not entirely comprehensive. To make this approach relatively easy to use, we built only two dimensions into it, leaving out others. For example, speed in implementing projects is another such dimension that could be a source of variation.

- May be difficult to implement. The demanding framework with two dimensions may be difficult to apply in certain corporate cultures. Examples are companies that are not mature in project management or have a long tradition with their industry's dominant project management models.

In summary, when customizing the project management toolbox by project type, follow these guidelines:

- Use the two dimensions we described or adapt them to your needs.

- Classify your projects and their SPM processes into four types.

- Match each SPM process with the proper toolbox, supporting each managerial deliverable with specific tool(s).

Which Customization Option to Choose?

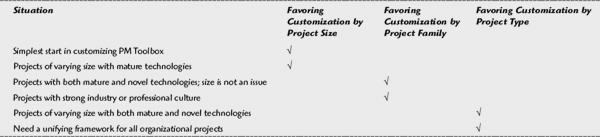

We offered three options for the customization of the project management toolbox. Each has its advantages and risks and fits some situations better than the others. To decide each one to select, refer to Table 16.6. Customization by project size is the right option when an organization has projects of varying size and needs a simple start toward more mature forms of the toolbox customization. In addition, projects of varying size characterized by mature technologies lend themselves well to this customization. If an organization has a stream of projects that feature both mature and novel technologies but project size is not an issue, customization by project family may be the first option. This is also the option to go for when projects are dominated by a strong industry or professional culture.

Table 16.6: Project Situations That Favor Each of the Three Options for Customizing PM Toolbox

Customization of the project management toolbox by project type is also favored in certain situations. One of those situations is when an organization has lots of projects that significantly vary in size but also in technical novelty, spanning from low-tech to high-tech. Organizations searching for a unifying framework that can provide the customization for all types of their projects—from facilities to product development to manufacturing to marketing to information systems—may find customization by the project type an appropriate choice for this purpose.

Once one of the customization options has been selected, there is a need to plan for its implementation. Here are steps for it:

- Set the desired level of the customization

- Establish the current level of the customization.

- Identify gaps between the current and desired customization.

- Act to provide the desired customization.

These steps are very similar to those for strategic alignment of the project management toolbox. They require a clear definition of where the company wants to go with the customization and a shared knowledge of where the current toolbox is.

Then establishing the gaps between the two is possible, prompting the development of a management action plan to guide the customization as described in each of the options. When the toolbox has been customized, it will be more effective if continuously improved.

Improve Project Management Toolbox Continuously

The purpose of this task is to put in place the rules for continuous maintenance and improvement of the customized toolbox. Without such improvement, the toolbox will gradually deteriorate, losing the ability to support the SPM process, project management strategy, and eventually, the competitive strategy of the organization [10]. Avoiding such a predicament and instead sustaining an effective toolbox can be achieved through the following steps:

- Form a project management toolbox improvement team.

- Identify mechanisms for improvement ideas.

- Follow improvement process.

Form an Improvement Team. The toolbox improvement team is usually part of the process team responsible for designing and managing the project management process. This team has the total responsibility for simplifying, improving, and managing the implementation of the project management toolbox. Each team member owns a piece of the toolbox, and overall, the responsibility should be distributed as evenly as possible across the team. When forming a team, it is important to understand that management enforces, while the team operates and owns the toolbox. Because it is mostly project managers that must use the toolbox, we recommend that the majority of the toolbox team members should come from the ranks of project managers.

Identify Mechanisms for Improvement Ideas. Ideally, there should be a continuous stream of suggestions and ideas to improve the customized toolbox. To secure such a stream, you can require that project teams at the end of the project perform postmortem reviews. If the reviews find a need to change the toolbox, the team should submit a change request. Besides, change requests may come at any time from anyone involved in projects. Note that requests are not the only way to collect the toolbox improvement ideas. A survey or management's periodic talk with members of the organization or small focus groups may serve this purpose as well.

Follow Improvement Process. This process defines steps in acting upon change and deviation requests, as well as an escalation procedure, in case the requests are turned down and those proposing them want them to be evaluated by management. Change requests are suggestions for making changes to the toolbox, most frequently coming from project teams. Quickly collecting and responding to them is of vital importance. Also significant are requests to deviate from the customized toolbox. If appropriate, the deviation requests should be allowed in order to make sure the toolbox is flexible. These are requests to deviate one time only from some part of the project management toolbox. Since they are submitted while the project is in progress, it is important to respond as soon as possible. Later, the requests can be evaluated to determine if the toolbox should be adjusted.

Final Thoughts

When it comes to managing projects, the toolbox has been one of the most critical things to learn. We would like to point out a few lessons we believe are most important from this book.

First, companies adopt project management to support the company's competitive strategy, which, in turn, has the task of creating competitive advantages that are so vital in outperforming their rivals in the market place. However, this support is often delivered through the SPM process, a disciplined and interrelated set of phases, deliverables, and milestones that each project goes through.

Second, companies can use project management tools to produce specific managerial deliverables in the SPM process. As a matter of fact, this is what the conventional purpose of each of the tools was. Examples, of course, can help get the point across. If we need to define the project scope, we can use the Scope Statement and WBS tools for this purpose. Similarly, faced with the problem of speeding up the project schedule, we can enlist the help of the Schedule Crashing tool or perhaps the Critical Chain Schedule. This, of course, calls for good knowledge of the individual tools, a reason for our decision to cover so many tools in this book.

Third, companies can use the tools to build the project management toolbox. In this manner, the tools become basic building blocks of the SPM process. Conceived as a set of predefined tools that are capable of completing the whole set of SPM process's managerial deliverables, the toolbox helps us go the full circle—the toolbox supports the SPM process that helps deliver project management strategy to support the competitive strategy that generates competitive advantages.

We have argued in this book that companies have a clear choice in using project management tools: They can go for the tools one at a time, or they can use the toolbox. Project managers can reach a certain managerial deliverable with one tool at a time, or they can attempt to leverage the toolbox through SPM process across all their projects. There are organizational costs to the project management toolbox as we have described it. This mode of operation calls for making a conscious choice of tools for the toolbox and aligning it with the competitive strategy of the company. It also requires making a smart decision on how to customize the toolbox—by project size, family, or type. In addition, companies need to be smart in how they continuously improve the toolbox.

But these are no more than details, as important as they may be. On a fundamental level, companies need to decide whether they want to think and manage in a project management toolbox mode. To us, the choice is clear. Individual tools used one at a time provide an outstanding systematic procedure that organizations have used to produce individual deliverables. But such a focus may no longer be suitable for organizations to win in the marketplace. The demands have changed as organizations manage more and more projects—faster, cheaper, better. Such changes necessitate new best practice; one that puts a strategically-aligned and customized project management toolbox in the center of the company's competitive stage.

References

1. Cooper, R. and E.J. Kleinschmidt. 1994. “Determinants of Timeliness in Product Development.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 11(5): 381–396.

2. Shenhar, A. J. 2001. “Contingent Management in Temporary, Dynamic Organizations: The Comparative Analysis of Projects.” The Journal of High Technology Management Research 12: 239–271.

3. Smith, P. and D. Reinertsen. 1990. Developing Products in Half the Time. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

4. Pinto, J. K. and J. G. Covin. 1989. “Critical Factors in Project Implementation: A Comparison of Construction and R&D Projects.” Technovation 9: 49–62.

5. Harrison, J. S. and C. H. S. John. 1998. Strategic Management of Organizations and Stakeholders. St. Paul, Minn.: South-Western College Publishing.

6. Brown, S. L. and K. M. Eisenhardt. 1997. “The Art of Continuous Change: Linking Complexity Theory and Time-Paced Evolution in Relentlessly Shifting Organization.” Administrative Science Quarterly 42: 1–34

7. Tatikonda, M.V. and R. S. Rosenthal 2000. “Technology Novelty, Project Complexity, and Product Development Project Execution Success: A Deeper Look at Uncertainty in Product Innovation.” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 47(1): 74–87.

8. Shenhar, A. J. 2001. “One Size Does Not Fit All Projects: Exploring Classical Contingency Domains.” Management Science 47(3): 394–414.

9. Shenhar, A. J. 1998. “From Theory to Practice: Toward a Typology of Project-Management Styles.” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 45(1): 33–48.

10. Juran, J. M. 1992. “Managing for World-Class Quality.” PM Network 6(4): 5–8.