6.

KEEPING TRACK OF REAL ESTATE TRANSACTIONS

Many of the bookkeeping standards for rental property are different from those for other businesses. For many first-time real estate investors, the difficulty arises from the mix between personal and investment uses of property.

If you begin by converting a home that you use yourself—a vacation home, for example—you need to track personal and investment use carefully. You also need to document how you break down the usage. Probably the most reliable method is to record the number of days the property is assigned to personal use and to investment use.

A second problem arises when you convert a property during the year. Some people find themselves in the real estate business when they move from their current house to a new one. Instead of selling their existing primary residence, they convert it to a rental. This decision used to be made to avoid taxes on a sale. However, under current federal rules, you are allowed to sell your primary residence tax free. This rule applies up to $500,000 in profit (for a married couple) or $250,000 (for a single person), as long as you have used the property as a primary residence for at least twenty-four months during the past five years.

This tax-free sale provision in the law is a considerable benefit for homeowners. There is no limit on the number of times you can sell your primary residence, as long as you have used that home as your primary residence for at least twenty-four months. As you can have only one primary residence, the timing is restricted. But compared to the past, when you had to buy a home of equal or greater value to defer taxes, the current rule is more favorable. For many empty nesters, needing a smaller home once children leave home, the past requirement meant that the overly large home had to be kept or, upon its sale and relocation to a smaller home, a large tax burden had to be met.

Even with the ability to escape taxes on the profit from selling your home, you might decide to convert to a rental for extra income. For example, the current market may not be strong enough to produce a profit from the sale of your current home. Converting it to a rental is one method for delaying the decision to sell until the market price rises. Of course, given the time restriction for avoiding taxes on a profit, you could end up paying capital gains tax on the property later. If five or more years pass, you would not be allowed to enter into a tax-free sale. In that case, one solution would be to move back into the home for twenty-four months and then sell with no tax liability.

Under any circumstances in which a specific property is a combination of personal and investment use, careful documentation is essential. If you convert your residence during the year, some portion of expenses will be personal (interest and taxes, for example, will be itemized deductions), and the rest of the year will represent investment expenses.

![]()

KEY POINT Some expenses are both personal and investment related to some degree. These expenses must be broken out and documented properly. The time may come when you will need to explain how you decided to assign a portion of an expense between personal and investment use.

SEPARATING PERSONAL AND INVESTMENT EXPENSES

The solution to the mixed-use problem is documentation. You must contend with this problem in one of three circumstances:

1. When an expense includes both business and personal usage

2. When a property is used only part of the year as an investment

3. When a property is used year-round, partly as your residence and partly as a rental

BUSINESS/PERSONAL MIX

Some expenses can include both personal and rental portions. Some examples:

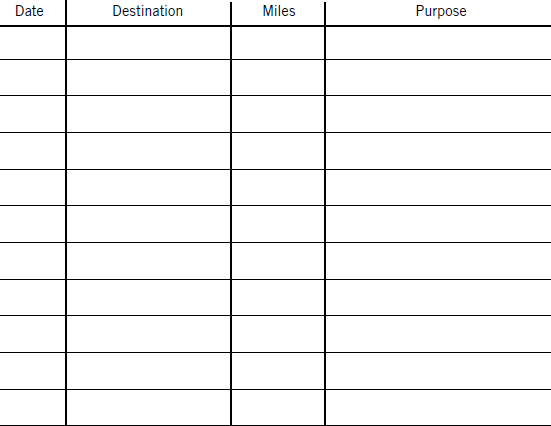

Automobile Expenses. You may use your personal automobile for rental activities. For example, you need transport to examine potential rental properties; to make trips to collect rents; to meet with prospective tenants; to take garbage to the dump; to move appliances or furniture; to keep an eye on the property; and to visit your accountant, attorney, or real estate broker. Any investment use of your automobile is deductible as an investment expense. If you use your personal car or truck in this manner, the most likely method for calculating a deduction is going to be based on the precise number of miles. You are allowed to claim a specific amount per mile as a deduction. You need to keep a log of your automotive expenses, which includes the date, destination, miles traveled, and purpose of each trip. Use an expense log such as the one shown in Figure 6-1.

To claim a deduction based on mileage, you must have owned the vehicle and used the mileage method in the first year of ownership (you cannot switch back and forth between mileage and depreciation methods). If you lease your vehicle, you have to use the standard mileage method for the entire lease period.

VALUABLE RESOURCE To read all about the tax rules for deductibility and documentation of automotive expenses, download the free IRS publication, “Travel, Entertainment, Gift and Car Expenses” at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p587.pdf.

The alternative method includes calculating the business portion and then deducting the applicable cost of gas and oil, repairs, insurance, new tires, license and registration fees, and depreciation. This method is more complex than the calculation based on mileage but could result in a higher deduction, especially if you use your automobile extensively to manage rental properties.

The standard mileage allowance changes from year to year (the IRS releases the new figure in January for the previous year). As of 2015, the standard mileage rate was 57.5 cents per mile. This mileage allowance does not include parking fees and tolls, which are added separately. Whichever method you use, if it involves more than one vehicle, you have to perform the computations and keep records for each vehicle. If you own several rental properties, it could make sense to buy a truck and use it exclusively for real estate activities.

Landscaping Equipment. Some rather simple acts can complicate your bookkeeping. For example, if you own a riding mower that cost $1,200 and you use it occasionally to mow the lawn of your rental property, a deduction has to be figured. Based on the degree of usage, this equipment is partly a personal asset and partly an investment asset. There is no deduction for personal use, but as an investment asset you are entitled to depreciation expenses. However, you can depreciate the asset only to the degree that it is used as part of your investment activity. If you have only your own lawn and the rental property lawn and you use the mower equally for each, the breakdown is probably fifty-fifty. This is a simple calculation. But the question is complicated if the circumstances are not so straightforward. For example, if your rental property is two acres but your personal property lies on a 50×100-foot lot, then your investment expense is much higher. You may need to mow 80,000 square feet of lawn at your rental property, versus only 3,000 square feet at your home. In this example, investment expense would be 96 percent of the total (80,000 feet divided by 83,000 feet). This breakdown would be easily documented, especially if you had purchased the riding mower specifically to take care of the rental property. In such a case, it would simplify your bookkeeping to purchase the riding mower as an investment asset and use a smaller, cheaper mower for your residence.

This example illustrates that some decisions you need to make in managing your real estate investments can create complexities. You could end up with a considerable investment in landscaping equipment—mowers, garden tools, soil and treatments, and more—especially if you own more than one rental property. Keeping these items separate from your personal-use items helps to keep your books clean and simple.

Cell Phone. Your cell phone expenses have to be split between personal use and investment-related activities. Due to the nature of investment business, your deductible expenses will probably be minimal. If you can document a substantial portion of investment-related phone usage, you could justify deducting a portion of the monthly service charge and data usage. If you claim investment use of your personal telephone, you must maintain a telephone log and be able to identify those calls directly related to investment activity.

Office Supplies. The office supply requirements for running your property operation are going to be limited, though your setup expenses could be considerable. These expenses include paying your bank for printing checks and purchasing a supply of paper, rent receipt forms, accounting worksheets, and other office tools. These expenses should all be paid for out of your business account and kept separate from the items you use at home.

When you buy items you use for operating your investments, you should purchase them separately from other, personal items. While the amount of money involved is probably going to be small, it is a good record-keeping habit to establish.

If you purchase a combination of business and personal items, break the purchases out on your receipt. When information is entered in the books, the portion that goes to personal use should be identified as draw (i.e., money drawn out of the investment funds for personal use) and not as an expense. However, it is cleaner and easier to document if you make separate purchases, one from a personal account and the other from your business account or credit card.

Professional Fees. Everyone needs to use the services of an accountant, a tax expert, or an attorney at some point. You need to break down combined use so that you claim only those expenses that you are allowed to as investment expenses.

For example, your attorney may advise you on tenant issues, approving the rental application, rental contract, and other forms you use to ensure that they comply with local and state laws. The attorney may also help you if you ever need to evict a tenant or go to court for other disputes. At the same time, your attorney advises you on writing your will, buying or selling property, and other issues not related to your rental activity. Therefore, the attorney’s bill must be itemized as well. The nondeductible portion has to be excluded as an expense and identified in your payment as a draw. Or, if the amounts are large enough, you can write two checks to the attorney and even request separate invoices. The payment from your investment account would pay only for deductible expenses, and your personal check would cover everything else.

The same rule applies if you use the services of an accountant. However, it gets more complicated because preparing your return includes both personal and investment schedules. You may need to ask your accountant to estimate the breakdown for you, identifying the portion of the fee that applies to real estate activities. That portion can then be paid from your investment account and the balance paid from your personal account. A similar breakdown may be necessary if you meet with your accountant during the year for any tax planning and related discussions. Ask the accountant to estimate the time that applies to real estate activities so that your payment can be applied easily.

Home Office. Rules for using an office in your home are very specific, and the terms for deducting these expenses are difficult to meet. It is also worth noting that claiming an expense for an office in your home can serve as a red flag for possible audit. Given the likelihood that the amount will be small, it may not be worth the trouble to claim this deduction.

The general rule for qualifying a home office deduction is: You must use a specific space 100 percent of the time and 100 percent for business use. Having a desk in the corner of the dining room doesn’t qualify because the dining room is used for other purposes. You would have to use a room for no purposes other than keeping track of investment properties. That means you could not use that same room as a guest room, for example.

The deduction would be limited as well. If your home office is 400 square feet and the total space in your home is 2,400 square feet, you can deduct one-sixth of home expenses, including utilities, insurance, taxes, mortgage interest, and depreciation. Considering the limitations, the total deduction is going to be quite small and probably not worth the effort or the exposure to possible scrutiny by the IRS. If you decide to deduct the home office, be prepared to carefully and thoroughly document how you arrive at the amount of expense you claim as a deduction.

VALUABLE RESOURCE Download the free IRS publication “Business Use of Your Home” to read all the rules for documentation and deductibility, at the IRS Web site, https://www.irs.gov/uac/about-publication-587.

PART-YEAR RENTALS

If you own a second home or vacation home, you may find it desirable to rent it out for part of the year. This is a sensible way to cover part of your costs and to obtain tax benefits at the same time. You need to divide all expenses on the basis of personal versus investment use. For example, if you always spend three winter months in your second home and rent it out for the rest of the year, you are entitled to a three-quarters deduction of annual investment expenses.

The property has to be available as a rental for the entire period you intend to deduct investment expenses. It is not enough that the house is empty. It has to be advertised and available. So, if you advertise the house for nine months but only rent it out for five of those months, you should still be able to claim three-quarters of the annual expenses as investment related. This relates specifically to property taxes, interest, and insurance. (Property taxes and interest are included as itemized deductions for the period of personal use, but no other expenses are deductible.)

For other expenses, such as insurance and utilities, you are allowed to deduct the portion of the total equal to the investment usage. In the case of utilities, you may also deduct the bills for the specific months that the property is rented out. Depreciation—which is an allowance each year—is deducted on a percentage basis. For example, if the property is used 75 percent of the year as a rental, you first calculate the full-year depreciation and then deduct the applicable percentage.

MIX OF RESIDENTIAL AND RENTAL USE

The division of expenses between personal use and investment use is especially complex when you use a single property in both ways at the same time. If you rent out part of your home, you can deduct a portion of all expenses of the household—property taxes, interest, insurance, utilities, repairs and maintenance, and landscaping, for example. Taxes and interest (the personal portion) are included as itemized deductions, while the rental portion of all other expenses is included as investment expense.

If you have a separate building on your property, often called an additional dwelling unit (ADU), the calculation of expenses can be quite simple. If the unit has separate utility meters, for example, division of utilities is clear. If you know the cost of constructing a separate unit, you also have an exact figure for the improvement, which serves as the basis for depreciation. It is more likely, however, that you will not have separate utility meters or a precise figure for the cost of the rental unit. If you cannot easily separate the ADU’s value from the main house, you must divide the basis using another method. The same guideline applies when you rent out part of your house. For example, a section of your house may have its own entrance and contain its own kitchen and bathroom. Even though it is in the same building, it is completely separate from your residential area.

Calculating Percentage of Square Footage. The most reliable method in this situation involves calculating square footage. The rental area, as a fraction of total square footage, is converted to a percentage of the total, and that percentage indicates the portion of expenses that can be deducted as investment expenses.

![]()

EXAMPLE: If your total area is 3,000 square feet, and 900 square feet is the size of the rental area, you can deduct 30 percent of total household expenses. The division is complicated if you rent out the area for only part of the year. If your house is 3,000 square feet, and you rent out 900 square feet, but only for nine months, you have to reduce the allowable portion to three-quarters (nine out of twelve months) as follows:

(a) $900 ÷ $3,000 = 30%

(b) 9/12 of the year x 30% = 22.5%

![]()

Figuring Depreciation. When you claim depreciation for a rental area, you have to apply the same percentages. For example, if you originally bought your house for $180,000 and the land is worth $40,000, then $140,000 is subject to depreciation (you are not allowed to depreciate land). Based on a period of 27.5 years (the depreciation period for residential real estate), you would calculate depreciation using the same percentages from the previous example, as follows:

(a) $140,000 ÷ 27.5 years = $5,091 (full-year depreciation allowance)

(b) $5,091 × 30% = $1,527 (applied to rental area)

(c) $1,527 × 9/12 = $1,145 (part-year depreciation allowance)

So there are several qualifying restrictions when claiming depreciation in these circumstances. Land cannot be included, you reduce the full-year depreciation to reflect only the portion of the home (30 percent in this example) that is rented out, and you further reduce the dollar value when the rental occurs for only a portion of the full year (here 9/12, or 75 percent, of the year).

IMPORTANT In calculating depreciation, you have to base the amount you claim on the original basis in the property. If you bought your home many years ago for $85,000 ($50,000 for the building and $35,000 for the land), you have to base your depreciation on the $50,000 value—even if your property is worth much more in today’s market.

TRACKING SPLIT EXPENSES THROUGH YOUR SYSTEM

Great care is required to keep track of any expenses that you split. Keep good records of the assumptions you use when splitting expenses between personal and investment use. A simple worksheet can be used to make your calculations, and this worksheet should be included with your permanent tax records for each year.

DO THE BREAKDOWN RIGHT AWAY Make the adjustments at the time that you enter the expenses into your records. If you are dividing a utility bill between personal and investment use, for example, calculate the breakdown when you make the payment. The least desirable method is to go back at the end of the year and calculate all of the divisions of expenses; it makes more sense to do the split as you make each payment.

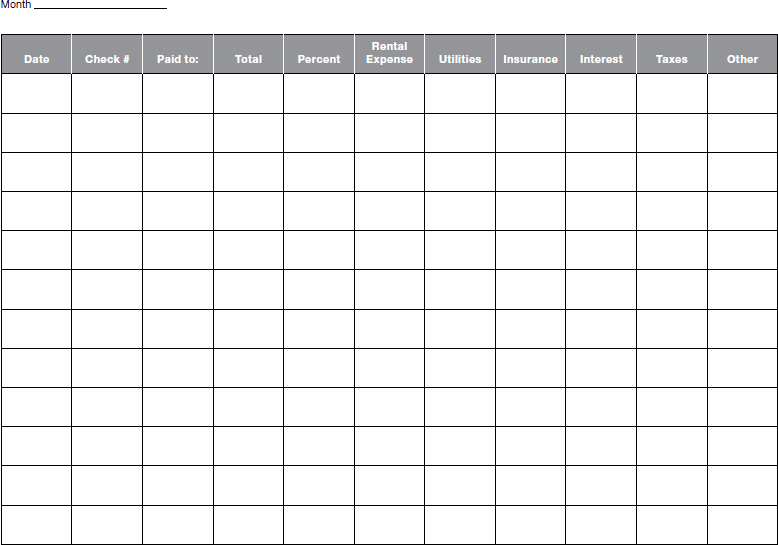

HOW TO ENTER SPLIT EXPENSES

Recalling the advice that you keep a separate checking account for investment activity, how do you make an entry for expenses that are partially investment and partially personal in nature? Since you want to be able to completely document and track all expenses that you claim as deductions, you have four choices:

1. Pay the full bill from your personal account and make a “memo” entry in your investment payments record. One simple method is to pay the bill from your personal account and, at the same time, record the investment portion in your rental activity books. Cross-reference the personal check number so that it can be traced back easily to the actual payment. While this method simplifies the transaction, it requires two steps. The key is to remember to record the investment portion. In an effective bookkeeping system, the majority of entries are tied to a cash transaction, a deposit, or a check. In this example, you need to enter an expense by making a memo entry, a transaction that is not tied to a cash transaction. The idea works as long as you remember to make the entry; it fails if you overlook that extra step.

2. Pay the full bill from your investment account and exclude a portion. As an alternative, you could pay the entire expense from your investment account and record the personal portion as a nondeductible expense. There are a couple of problems with this method. First, it violates the general guideline of keeping personal and investment expenses separate. Second, it requires you to deposit extra cash into your investment account to cover your mortgage payment, property taxes, insurance, and other expenses. To track cash flow, it is more desirable to keep the investment account strictly dedicated to investment activity, with as few exceptions as possible.

3. Pay the investment portion from the investment account. Another idea is to pay nondeductible expenses from your personal account and to pay investment expenses from your investment account. You can either transfer funds to your personal account and write a single check, which may be the most practical method, or you can write two checks each month, one for the personal portion and the other for the investment portion. This keeps the division clean and relatively simple but requires additional work, not to mention writing more than one check for each payment of utilities, insurance, and your mortgage.

4. Pay the investment portion from your business account to yourself. Write a check to record the investment expense, and deposit that into your personal account. This is cumbersome, but it solves the problem of keeping each side separate.

Using a worksheet to keep track of mixed-use expenses is an essential part of your documentation. A sample worksheet is shown in Figure 6-2.

DOCUMENTATION GUIDELINES

Each and every transaction (with few exceptions) needs to be documented by way of receipt, invoice, statement, voucher, letter, contract, or other means. In addition to being able to document all transactions, the properly maintained set of books needs to have an audit trail. That means it has to be possible for anyone to track everything through your records, from original document down to the final entry and, ultimately, onto your tax return.

How do you document all of your transactions, without getting into a time-consuming and space-consuming paper war? You need to keep your paperwork, of course. But you also need to be able to control it. You will find that as a real estate investor, you need to keep at least as much paperwork as is required by any other business, if not more. You need to keep property tax statements, tax notifications from mortgage companies, monthly statements for utilities, and invoices or statements for insurance, repairs, office supplies, and any other expenses you claim on your income tax return.

You may also need to keep detailed logs for use of a personal automobile or truck and for investment-related use of your telephone. The combination of invoices or receipts and specialized logs satisfies the need for documentation. If you spend a lot of cash, you can estimate the amount of deductible expenses; however, it is preferable to keep the receipts and record the expenses in your books. The estimate may be reasonable, but you are far more likely to miss expenses to which you are entitled when you do not keep all of your receipts.

WHAT TO DO Store your original statements, invoices, and other receipts in a folder dedicated to each year. Unless you have an exceptionally high volume of transactions, you should be able to keep expense documents for one full year in a single folder. Remember the general guideline: You should have a receipt for every expense you claim.

LEAVING A TRAIL

In addition to keeping all of your receipts, make it easy for anyone to track payments through your checking account. The easiest way is to mark your check stubs, which provides you with a double benefit. First, it explains how the payment is broken down among two or more rental properties. Second, it helps you to properly distribute a payment among those properties when you make the entry into your bookkeeping system. For example, if you pay

your property tax bill for three separate properties, break down the payment, identifying each portion by property address. Use the same system when paying insurance, utilities, and other expenses to a single source when more than one property is involved.

WHEN YOU HAVE NO RECEIPT

What do you do when you make a payment but have no receipt? For example, let’s say you spend $75 on hardware for a repair you’re taking care of at your rental property, but the receipt gets lost or thrown away. In that case, write out a record of the payment. Write down the date, the store, the approximate or exact amount of cash you spent, the merchandise you bought, and the property address. Put this paper in your system as a replacement for the lost receipt.

CHARGING YOUR PURCHASES

If you are spending a lot of money in this way and you keep losing your receipts, one possible solution is to use a credit card solely for rental-related expenses. When you charge your purchases, you get an automatic receipt at the point of purchase, and you also get a monthly statement from your credit card company. It is desirable to keep the receipt, if only to ensure that you don’t get charged any purchases in error, but if you do lose a few receipts, your record of purchases shows up on each month’s credit card bill. You can achieve the same convenience using a debit card for your investment checking account, but in that case, you also have to remember to write down the purchases you make in your checking account register. If you are prone to lose receipts, you are also likely to forget to write down your debit card purchases.

THE VALUE OF CONSISTENCY

Most systems succeed because the system itself and all of its facets are consistent. The methods employed are the same throughout, so anyone looking at the books and records can easily find what they need. The uniformity of the system is the key to efficiency.

If a system has a series of unrelated methods, or if you do things differently each time you record transactions, it becomes impossible to track the movement of money. Once you decide to do things a certain way, stay with it. If your practice is to pay all water bills with a single check and then break down the payment by property, do it the same way every month. Or if you want to write out separate checks, follow that procedure consistently throughout the year. Record items in the same manner and with the same timing so that monthly expenses show up once per month. The alternative—doubled-up expenses one month and none the next—makes the system difficult to follow and understand.

WRITING FILE MEMOS

Some circumstances make it difficult to understand your reasoning later. For example, you may enter information a specific way one month and not remember what you were thinking the following month. This is especially true with real estate, when you allocate expenses among properties, pay bills in a particular manner, or assign a payment to a specific property. When you make decisions that might not be clear later on, write a file memo, a reminder to yourself about what your reasoning was when you made the decision.

The file memo can save a lot of time and trouble later. It can become an important part of your record-keeping system and can aid in clarifying what would otherwise be a confusing or complicated transaction.

HOW LONG SHOULD YOU KEEP YOUR RECORDS?

You have to contend with a number of special accounting problems whenever you own rental real estate. In some respects, operating rental property is going to involve more paperwork and more complexity than operating many other businesses. However, you’ll be on safe ground if you make sure to keep all of your documents in a logical manner—while also minimizing the time you spend on bookkeeping chores.

Another accounting problem is that you probably need to maintain some of your records for a longer time period than for most types of business. As a general guideline, you should keep records of all deductions you claim for at least three years from the due date of your tax return. For example, your 2017 tax return was due on April 15, 2018. So you should plan to hold onto all of your documentation until April 15, 2021, three years later. If you file for an extension of time to file your tax return, that also extends the retention deadline. For example, if you defer your filing date until August 15, 2018, you need to keep your records until August 15, 2021, three years from the filing deadline.

EXCEPTION You need to maintain your records of the property cost and any subsequent improvements until at least three years from the filing deadline for the year in which you sell the property. This means that if you hold onto a rental property for twenty years, you also have to keep records of your purchase and any capital improvements throughout the entire period. This is because you will be claiming depreciation throughout the entire period, based on your original basis (usually the amount you spend) in the asset. If you will be reporting a capital gain or loss upon sale of the property, you must be able to document your original basis.

TAX-DEFERRED EXCHANGES

The record-keeping requirement can extend even further back than your purchase. If you acquire rental property through a tax-deferred exchange (see Chapter 9), you also must keep the records for the property you owned before, just to be able to show how you arrived at your basis in the new property.

![]()

EXAMPLE: You bought your first rental property for $100,000 several years ago and held it for five years. During that time, you may have claimed $14,500 in depreciation. When you sold the property last year, you received $130,000. Rather than being taxed on your profit, you deferred that profit in a tax-free exchange—selling one piece of real estate and replacing it with another of equal or greater value. You may have bought a new rental property for $145,000, for example. In this case, your basisin the new property is not $145,000; it is your purchase price minus any deferred gain on the previous property. See Tables 6-1 and 6-2.

![]()

TABLE 6-1. STEP 1: CALCULATING THE PROFIT ON THE PREVIOUS PROPERTY ($)

Sales price, previous property |

130,000 |

Minus original cost ($100,000) adjusted for depreciation ($14,500) |

−85,500 |

Net basis in the previous property |

44,500 |

TABLE 6-2. STEP 2: CALCULATING THE ADJUSTED BASIS IN THE NEW PROPERTY ($)

Purchase price, new property |

145,000 |

Minus: Net basis in the previous property (calculated in step 1) |

−44,500 |

Adjusted basis in the new property |

100,500 |

KEY POINT The purpose in explaining all of this is to demonstrate why you may need to keep your records of rental real estate for many years beyond the basic three-year requirement. To document a tax-free exchange, you may need to track basis and adjustments back for many years.

Many special rules and requirements apply to real estate investments that are not experienced elsewhere. The requirements for figuring depreciation, adjusting rental property basis, and even keeping expenses separate between rental and nonrental use (or part-year use of property as a rental) all demand special documentation and tracking. Your bookkeeping and record-keeping systems have to accommodate these special demands. If you understand the transactions and the need for such records, it will not be difficult to set up your books to meet all of these requirements. The next chapter goes to the next step: setting up your books so that you can handle all of the special transactions as efficiently as possible.