7.

CREATING A TIMELY AND EFFICIENT ACCOUNTING SYSTEM

Resolving the special problems concerning your bookkeeping requirements is an essential first step in developing an efficient system. As demonstrated in Chapter 5, these problems include allocating expenses to specific properties; managing expenses that are partially investment related and partially personal in nature; breaking down expenses, based on the use of a property as a rental for part of the year; and allocating expenses in a property that has both personal and investment use.

Once you have resolved these problems and identified the most efficient method for dividing up expenses and documenting how that is done, you next need to formalize your bookkeeping so that entries can be made in a timely and efficient manner. It is essential to keep your books current; at the same time, you want to spend as little time as possible to maintain your records, while creating an efficient and complete system.

SETTING UP YOUR ACCOUNTS

Every bookkeeping system consists of a series of accounts—records for each specific type of transaction. In your real estate bookkeeping system, you must keep track of several different types of accounts:

![]() Assets. By definition, assets are the value of property you own, including cash, property improvements, and land (adjusted for depreciation), as well as equipment used in your investment activity.

Assets. By definition, assets are the value of property you own, including cash, property improvements, and land (adjusted for depreciation), as well as equipment used in your investment activity.

![]() Liabilities. The most obvious and important liability is going to be the mortgage balance you owe on one or more investment properties. This liability is reduced each month as you make payments. There are current liabilities (the sum of payments due over the next twelve months) and long-term liabilities (the balance owed on each mortgage).

Liabilities. The most obvious and important liability is going to be the mortgage balance you owe on one or more investment properties. This liability is reduced each month as you make payments. There are current liabilities (the sum of payments due over the next twelve months) and long-term liabilities (the balance owed on each mortgage).

![]() Income. The rents you receive from tenants have to be tracked by property.

Income. The rents you receive from tenants have to be tracked by property.

![]() Expenses. These accounts are used to record your deductible investment expenses. You need to track expenses both by category and by property.

Expenses. These accounts are used to record your deductible investment expenses. You need to track expenses both by category and by property.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ASSETS AND LIABILITIES

The difference between assets and liabilities represents your equity in properties. For example, if you buy a $125,000 property with $29,000 down and you finance $96,000, your equity is $29,000—the difference between the asset value and the liability.

In the initial transaction of purchasing a rental property, you must make a series of entries in your books. If you finance your $96,000 loan, your current liability will be the principal portion due over the next twelve months (which changes each year). This can be estimated and updated periodically; absolute accuracy will become important only when you present a summary of assets and liabilities to a lender. You also need to break out the value of land separately because you are allowed to depreciate improvements but not the land itself. (See Chapter 8 for an explanation of how to determine land and improvement values.) For the purpose of the initial entry, let’s assume that land is worth $40,000 and improvements are worth $85,000.

WHAT TO RECORD In this situation, you need to record (a) the asset, broken down between land and depreciable improvements, and (b) the liability, broken down between current (what you owe over the next twelve months) and long-term liability.

The entry for the initial transaction would involve setting up account values for all of the components of the purchase: cash paid out, asset accounts, and liability accounts. In the double-entry system, the entry looks like the summary in Table 7-1.

TABLE 7-1. DOUBLE-ENTRY SYSTEM ($)

In this example, the cash down payment is equal to your equity in the property. The sum of land and improvements minus the sum of the mortgage liabilities (current and long-term) equals $29,000, or your equity in the property.

WHY EQUITY DECLINES EACH YEAR

The equity as recorded in your books will decline each year as depreciation is recorded. The depreciation expense is offset by a reduction in the “improvements” asset. So depreciation accumulates over the period that you own the property, and the equity your books show in the property declines. This is one of the ironies of accounting. In real terms, your property is probably growing in value over the years, but the accounting rules show it falling. The reporting of assets, liabilities, and equity is unrealistic because it does not show the real current value. It shows the depreciated value of the asset, which is a basis for calculating tax liabilities, but it does not reflect the true value of your investment.

TRACKING ASSETS AND LIABILITIES

The formal recording of assets and liabilities is only required as part of a double-entry bookkeeping system. However, even if you do not use such a system, you still need to keep track of asset and liability values. For example, if you were to apply for financing on another property, the lender would want to know your liability as well as an estimate of the market value of properties. In an informal bookkeeping system, you need to track rental income and expenses paid, as well as asset values and liabilities. That can be done on a card system or simply by recording the breakdowns (between land and improvements, as well as between current and long-term mortgage liabilities). Then annual depreciation is figured out on a predetermined schedule, and the book value of the asset is recorded on the depreciation worksheet. So there are simplified and uniform ways to track these items without using double-entry bookkeeping.

RECORDING EXPENSES

A simple way to record expenses is by using a single-entry method. You track receipts and payments through your checkbook and calculate adjustments for interest and principal at the end of each month, or only a few times per year. A single-entry bookkeeping system is usually enough to track day-to-day expenses, and if you need to formalize your system beyond that, the adjustments can be done separately. If you use an online accounting and bookkeeping system, you do not even need to be concerned with which system you use; you simply enter information into the accounts, and the program does the rest for you.

YOUR INVESTMENT BALANCE SHEET

Your accounts are divided into two primary areas. The balance sheet accounts include assets you own, liabilities you own, and net worth (the difference between assets and liabilities). The income accounts include rents received and expenses paid. When you subtract expenses from rents, you end up with a profit or loss.

The assets, liabilities, and equity accounts represent your investment balance sheet. If you were to include information about your real estate investments on a loan application, you would report the balance sheet items in addition to showing activity in your rentals in terms of income, expense, and net profit or loss. These accounts are collectively referred to as “profit and loss” or, on a loan application, as an “income statement.”

You report rental income, expenses, and profit or loss in a specific sequence on your tax return; you also break down this information by property. Thus, your books have to include not only the breakdown by category but also a series of subaccounts for each property. If you maintain your books manually, you are likely to maintain subaccounts on one side of each account page, with a summary on the other. Figure 7-1 shows how this type of account appears. The debits and credits refer to the summary of all transactions, and the subaccounts break these down by property.

RENTAL INCOME

Figure 7-2 shows a typical form of account with both subaccount breakdowns (on the left side) and summarized entries (on the right side). This filled-in example also shows how entries are broken down using an account with subaccounts. In this example, rental income is reported for four different properties. Because income is a credit-balance account, the accumulated rents are shown as a growing credit balance through the year.

Why are rents reported as credits? Many people who have not been trained in bookkeeping find such rules confusing. Expenses are reported without parentheses, and income is reported with parentheses. The designation of rental income as a credit does not mean there is a loss, only that the values are reported in credit-balance accounts. This makes sense when you trace a transaction. When you receive rent, it increases your cash balance (a debit) and, at the same time, increases your rental income (a credit). The cash account reports additions as debits or plus accounts and payments as credits or deductions. A bookkeeper treats these debits and credits in a manner that keeps both sides the same. So every plus (debit) has a corresponding minus (credit) entry. The accumulation of income is accounted for on the credit side while expenses show up as charges on the debit side. Therefore, a typical rental-receipt entry would involve a debit to cash and a credit to rent income, as in Table 7-2.

TABLE 7-2. RENT RECEIPT ENTRY ($)

SINGLE-ENTRY BOOKKEEPING

Fortunately, you do not need to become an expert in bookkeeping and accounting to keep a simple set of books for your rental activity. However, it helps to understand some of the basic concepts. If you maintain your books on an automated system or spreadsheet, you can simply enter the information in the preset formats. If you keep books by hand, it helps to have a formalized entry system. Double-entry bookkeeping helps avoid errors, but it is not essential. In a single-entry system, you record all cash transactions in a single ledger, showing additions as plus values and payments as minus values. So a single-entry system operates just like your checkbook. The single-entry record can be summarized at the end of each month by tallying the totals for each account. Remember to keep track of all income and expenses by property as well.

In a typical single-entry system, a series of entries also tracks what is taking place in your checking account. If you maintain your checking account with adequate detail, you can use it as your primary bookkeeping source, without needing to duplicate information elsewhere. The entries in a single-entry bookkeeping journal would look like the example in Table 7-3.

This example can be set up in your checking account record. Because you need to track the type of transaction as well as identify each by property address, it makes sense to use the journal-format checking account, in which checks come three to a page and the running totals are maintained on a ledger sheet.

TABLE 7-3. SINGLE-ENTRY BOOKKEEPING JOURNAL ($)

![]()

KEY POINT Whether you use the simplified single-entry system or a more elaborate version of double-entry bookkeeping, the goal is to capture all of the information you need as entries occur. Make your bookkeeping as easy as possible, make sure it is complete, and to the extent it is practical, keep the activity separate from your personal records.

BREAKING DOWN LOAN PAYMENTS IN YOUR BOOKS

Each month’s mortgage payment presents special problems for you if your lender does not show how much goes to interest and principal. Most lenders do not provide you with a monthly breakdown, so you need to estimate the totals yourself.

Chapter 5 explained how a typical year’s payments would be broken down between interest and principal. Recalling the formula, the breakdown involves the following five steps:

1. Multiply the balance forward by the annual interest rate.

2. Divide the result in the previous step by 12 to arrive at this month’s interest.

3. Subtract the interest from the total payment you are making.

4. Subtract any impounds that you are required to pay from the total payment.

5. The result (total payment less interest and impounds) is this month’s principal.

Subtract this amount from the previous balance to arrive at the new balance forward.

You may need to apply this formula to each payment on a monthly basis in order to properly break down the various items. This is important because it enables you to track not only your profit and loss but cash flow as well. These are not the same. Interest payments and impounds affect your profits; however, the entire payment—including principal—affects overall cash flow. In real estate investments, cash flow may be more critical than actual profits. Because most people buy real estate for the long term, future profits may be expected and year-to-year profits may not be as important. For purposes of tax calculations, month-to-month profits do not reflect depreciation expenses, and depreciation itself is a noncash expense. So profitability has to be distinguished in two different ways: immediate profits and long-term profits.

IMMEDIATE PROFITS

Immediate profits refer to the monthly and annual reported profits. This number affects your federal tax liability. For example, you may have an after-tax positive cash flow while still reporting a net loss for tax purposes. This occurs because depreciation is calculated as an expense, although it does not involve a cash outlay. The tax benefits of investing in real estate are one of

many features that make it a desirable investment; however, most people are going to be far more concerned with net cash flow from month to month.

To demonstrate how you can have the combination of positive cash flow and a tax loss, consider this example: Your rental income is $6,800 for the year, and cash expenses come up to a total of $5,700 (interest on your mortgage, utilities, property taxes, and insurance). Depreciation is calculated as a deductible expense, but you don’t pay out cash. In this example, if depreciation is $2,000 per year, you will show a net loss of $900, which is calculated in Table 7-4.

TABLE 7-4. CALCULATED NET LOSS

Rent receipts |

6,800.00 |

Less: Cash expenses |

−5,700.00 |

Positive cash flow |

1,100.00 |

Less: Depreciation |

−2,000.00 |

Net loss |

− 900.00 |

This calculation has to be adjusted to allow for the principal portion of your mortgage payment. Although this is not a deductible expense, it is money being paid out, so it affects cash flow. For example, if this year’s principal payment came to $600, you would report positive cash flow of $500 ($1,100 predepreciation profit minus $600 for principal payments). The net loss of $900 remains unaffected.

![]()

KEY POINT In this example, the difference between cash flow and tax-reported loss is significant. It makes our point that you can achieve both, and, in fact, that is not uncommon. Depreciation is a major expense, and it has “tax savings value” in the sense that the expense reduces your taxes. A $2,000 annual depreciation for someone in the federal 39.6 percent tax bracket plus 4 percent state tax (total 43.6 percent) translates to a tax reduction of $872 per year (43.6 percent of $2,000).

LONG-TERM PROFITS

Long-term profits from real estate investments refer to the difference between your net purchase and net sales prices on each investment. As long as property values rise, you will want to continue holding onto properties. This assumes that (a) you are able to create a breakeven or positive cash flow each month and (b) you are willing to continue working with tenants. You are able to defer taxes on profits from real estate investments by selling property and exchanging it for later purchases of equal or greater net value, subject to some limitations (see Chapter 9). You may also avoid taxes by later converting a rental property to your primary residence. As long as you use the property as your primary residence for at least twenty-four months during the five years preceding the sale, profits will be free of tax. The exception: You have to pay taxes on profits equal to the amount of depreciation that was claimed during the period you used the property as a rental, which is called the recapture of depreciation.

ACCOUNTING FOR PREPAID INSURANCE AND TAXES

Impounds for property taxes and insurance may be added onto your payments. As a general rule, these expenses are payable twice a year; your lender collects the impound each month and then makes timely payments on your behalf.

If impounds are included in your monthly payment, it is not necessarily accurate to just assign those deductions to the taxes and interest expense accounts for each property. The applicable period may be different from the timing of impounds.

![]()

EXAMPLE: Your lender begins taking impounds when your loan is originated in September. However, property taxes are not payable until the following April for the first half of the calendar year.

![]()

TIMING DIFFERENCES

In this example, there are two timing differences. First, the impounds are withheld beginning in September, although the taxes relate to the following year. Second, the payment is not due until the following April, even though the expense applies from January onward. While this is a confusing problem, it is not difficult to manage in your books. Table 7-5 breaks down the timing differences for you, based on the example of a $1,200 annual property tax bill.

TABLE 7-5. TIMING DIFFERENCES, IMPOUND ACCOUNTS ($)

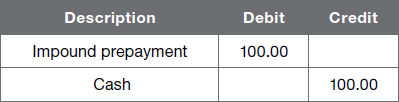

In this situation—where you have two separate timing problems to track—the easiest solution is to treat impounds as prepayments and to report the actual liability in the correct month. So, as each impound is withheld, the bookkeeping entry is shown in Table 7-6.

TABLE 7-6. IMPOUND PAYMENTS ($)

SPECIAL MONTHLY ENTRIES

When the liability is properly reported, the impound account is reduced, and the proper expense shown in that account. For example, in each month of the new year, the entry would be made as shown in Table 7-7.

TABLE 7-7. PROPERTY TAX IMPOUNDS ($)

This entry is made as a noncash transaction. The cash is paid out with each month’s mortgage payment, even though the impound amount is automatically placed into the prepayment account. Under this system, you would need to make a special monthly entry to show the adjustment. The overall result of making these entries is shown in Table 7-8.

TABLE 7-8. IMPOUND ACCOUNT ENTRIES ($)

GETTING THE TIMING RIGHT

This series of entries places the correct expense of $100.00 per month at the right time. The impound account has a perpetual balance of $400.00 because the original series of entries in this example began four months before the end of the year. Mortgage lenders invariably try to collect impounds in advance of the payment due dates. If you begin your mortgage term midway through a payment term such as this, part of your closing costs will include the liability for either taxes or insurance.

The point in making these adjustments is to make sure that the expense ends up in the correct month. The example of property taxes makes this point; the liability applies equally throughout the year. Impounds do not necessarily correspond to the applicable month. Even if you pay property taxes or insurance directly, some adjustment needs to be made.

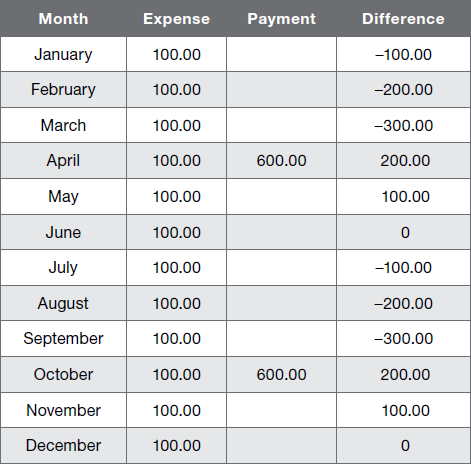

For example, you would reflect a debit to the expense each month throughout the year and offset that with payments, as shown in Table 7-9.

TABLE 7-9. MONTHLY CALCULATIONS ($)

MAKING SPECIAL ADJUSTMENTS FOR PROFIT AND LOSS

In this case, the expense occurs and applies to each month in advance of the payment date of the taxes that are due in April and October. Thus, the payments represent an effect on cash flow in those two months. However, to accurately report the profit or loss on real estate activity, you need to show one-twelfth of the total expense each month. A similar situation arises when dealing with insurance. The premium is probably due twice a year or quarterly, but the expense for each property should be shown each month as well.

IMPORTANT Timing differences can distort both profit and cash flow if not properly adjusted in your system. You need to track cash flow by property and in total so that you can know throughout the year what your actual after-tax net profit is, as compared to your original estimates. To compute the after-tax number, you need to include monthly taxes and insurance, even if you have not paid those bills yet.

ADJUSTING THE BOOKS MONTHLY

Real estate investors who are not well versed in accounting have to struggle with problems such as this unless they can come up with a simple and consistent method for adjusting the books. Reflecting each expense in the proper month helps make monthly and year-to-date profit analysis possible with accuracy. For most people, the problem involves knowing how to make the adjustments. If you want to keep your books simple but still make the adjustments, and if you know the monthly liability for periodically paid or impounded expenses, you can perform the adjustments on a worksheet as follows:

1. Write down a summary of income received and expenses paid for the month.

2. Calculate the estimated adjustments for property taxes and interest expenses.

3. Make an additional adjustment for the allowable depreciation, based on the annual allowance (see Chapter 8). Apply one-twelfth of the annual depreciation to each month’s profit number to get the true profit or loss.

4. If the results show a loss after adjusting for property taxes, interest, and depreciation, subtract the tax savings to arrive at the after-tax profit or loss.

5. To calculate federal tax savings, divide your total income tax by the taxable income on your latest year’s tax return. The resulting percentage is your effective tax rate. Multiply your net loss by this rate to arrive at the tax savings.

A worksheet for calculating after-tax net loss for both the current month and year-to-date totals is shown in Figure 7-3.

State Taxes, too. You may also need to adjust the effective tax rate to account for state taxes that you pay. As long as you receive a tax benefit from state taxes, that should be a part of the calculation. When your allowable deductions are figured differently for state tax purposes, the calculation may be more complicated. Since the purpose is to show the savings, simply recalculate what your tax liability would have been if real estate investment losses had been included. The combined federal and state tax liability is the amount to include on the worksheet.

DOCUMENTING SPECIAL RENTAL SITUATIONS

You are going to need additional documentation in three situations: mixed use of property, allocations between properties, and cash expenses.

MIXED USE OF PROPERTY

When a specific property is a rental for only part of the year, or if you rent out part of the home you use as your primary residence, you must divide expenses between the two types of use. For taxes and interest, the personal portion is reported on Schedule A (Itemized Deductions) and the investment portion is shown on Schedule E as an investment expense. The calculation between personal and investment use is worth making if your itemized deductions are marginal. For example, reporting a portion of your taxes and interest as rental expense could reduce itemized deductions enough so that you reduce your taxes more by claiming the standard deduction.

![]()

KEY POINT You might discover that you are better off claiming the standard deduction rather than itemizing. This will be true if your itemized deductions add up to a dollar value that is lower than the standard deduction.

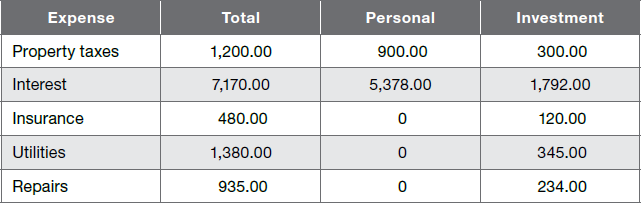

For all other expenses—utilities, insurance, and repairs, for example—you are not allowed to claim any personal expenses. However, the portion that applies to rental use is deductible as an investment expense. For example, if you use a property 25 percent as an investment and 75 percent for personal use, your expenses would be broken down as shown in Table 7-10.

TABLE 7-10. ALLOCATED EXPENSES ($)

In this example, the personal portion assigned as itemized deductions is only $6,278. This is less than the allowable standard deduction if your filing status is married filing jointly or head of household. So you would pay less tax by claiming a standard deduction unless you are able to claim additional itemized deductions. Whichever way this comes out, keep your calculations in order to justify how you break out the expense.

Breaking Down Personal vs. Investment Use: Part of your worksheet should be the precise calculation between personal and investment use of the property. If the entire property was used as a rental but for only a portion of the year, the calculation should be based on the number of days or months. For example, if you lived in the house from January 1 through September 30 and then rented it out from October 1 through December 31, the rental period was 25 percent (three months out of twelve). If you permanently rent out part of your property, the breakdown should be based on the square footage of rental space as a portion of total square footage. For example, if your total living space is 3,000 square feet and you rent out 750 feet, then the rental portion is 25 percent.

ALLOCATIONS BETWEEN PROPERTIES

Some expenses are properly allocated to a specific property. In the case of utilities, insurance, property taxes, and interest, it is easy to make this allocation. In the case of expenses that are not specific to a single property (e.g., legal or accounting fees, office supplies, or telephone), you can allocate a portion to each property or show nonallocated expenses as a separate category on your tax return.

![]()

KEY POINT If you decide to allocate expenses to each property, the most reliable method is to divide nonallocated expenses on the same percentage as total rents you collected. For example, if your total rents for the year were $22,600 and one property’s rents were $7,232, its share of the total would be 32 percent.

ACCOUNTING FOR CASH EXPENSES

The easiest way to get cash expenses into your system is to reimburse yourself based on receipts you save up. Simply write a check to yourself showing the breakdown by type of expense and for each property. If you have lost receipts, write a memo receipt noting the date, amount, property, and amount you spent. Try to avoid excessive expenses without proper receipts. The more documentation you keep, the better your bookkeeping system.

MAKING YOUR ACCOUNTING SYSTEM WORK

Even if you have to make a lot of cash transactions, you can ensure that your system captures all of your legitimate deductions, that every transaction can be proved and traced through your system, and that it does not become too time-consuming. Here are some guidelines for making your system work:

![]() Consider the practical over system requirements. No system is going to work for every possible situation. You may simply need to use cash a lot of the time based on the way you work, the kind of expenses you have, and your personal preference. So, even if your “rule” is that you do not use cash when you can write a check or use a credit card, there are going to be times when cash works better for you. This is a practical reality, and you can’t be expected to change your style just because the system would be more efficient, easier, and more consistent.

Consider the practical over system requirements. No system is going to work for every possible situation. You may simply need to use cash a lot of the time based on the way you work, the kind of expenses you have, and your personal preference. So, even if your “rule” is that you do not use cash when you can write a check or use a credit card, there are going to be times when cash works better for you. This is a practical reality, and you can’t be expected to change your style just because the system would be more efficient, easier, and more consistent.

![]() Remember to balance time against bureaucracy. If you are spending way too much time working on your books, you probably need to streamline your procedures. You want to spend as little time as necessary to get the best possible system. However, it often is the case that—in the interest of making the system thorough—a person who is not experienced in bookkeeping may create a system that is overly complex. Efficiency often means reducing the paperwork as much as possible. Reevaluate your procedures and look for ways to cut back on the time and paperwork requirements.

Remember to balance time against bureaucracy. If you are spending way too much time working on your books, you probably need to streamline your procedures. You want to spend as little time as necessary to get the best possible system. However, it often is the case that—in the interest of making the system thorough—a person who is not experienced in bookkeeping may create a system that is overly complex. Efficiency often means reducing the paperwork as much as possible. Reevaluate your procedures and look for ways to cut back on the time and paperwork requirements.

![]() If you need help, ask for it. Don’t let yourself get buried in the bookkeeping system. If you are overwhelmed and don’t know how to fix it, ask your bookkeeper or accountant to show you a better way. At times, the solution is automation.

If you need help, ask for it. Don’t let yourself get buried in the bookkeeping system. If you are overwhelmed and don’t know how to fix it, ask your bookkeeper or accountant to show you a better way. At times, the solution is automation.

![]() If you simply don’t enjoy bookkeeping, pay someone else to do it. There is no absolute rule that you have to do your own books. You may save money by not paying a professional, but that economy is worthwhile only if you are not having fun. To paraphrase the popular bumper sticker: “Friends don’t let their friends keep their own books.” You might enjoy the task and find it easy and fast. Or you may dread it and end up frustrated and buried in complexity.

If you simply don’t enjoy bookkeeping, pay someone else to do it. There is no absolute rule that you have to do your own books. You may save money by not paying a professional, but that economy is worthwhile only if you are not having fun. To paraphrase the popular bumper sticker: “Friends don’t let their friends keep their own books.” You might enjoy the task and find it easy and fast. Or you may dread it and end up frustrated and buried in complexity.