8.

HANDLING DEPRECIATION FOR RENTAL PROPERTIES

You are allowed to deduct expenses each year that pertain to your real estate investment activity. By definition, deductible expenses include interest, property taxes, utilities, legal and accounting fees, auto expenses, and any other items relating to managing and maintaining your property. As an investor, you also purchase capital assets and are entitled to deduct those costs as well; however, they cannot be deducted in a single year. They have to be depreciated over a specified number of years, called a recovery period.

The distinction between expenses and capital assets is an easy one to make. An expense, for the most part, relates specifically to the year in which money is spent. A utility bill is for services for the current month, and interest is calculated on each month’s outstanding mortgage balance. Some exceptions do occur. For example, you may have purchased business cards that last several years. The amount of such an expense is small, however, so it does not need to be treated as a capital asset.

In comparison to expenses, the cost of capital assets cannot be applied to a single year. They have value over many years, and the period is called the asset’s useful life. You are allowed to claim depreciation each year on a predetermined schedule, to write off a portion of a capital asset over several years.

The rules for depreciation are complex, and many elections, rules, and restrictions come into play in the calculation itself. Rely on your tax adviser to assist with determining the best depreciation elections to make. Remembering that your maximum real estate loss deduction is limited to $25,000 maximum per year, there are instances in which it makes sense to claim the least amount of depreciation each year, notably if your losses will be close to or over $25,000.

OVERVIEW: HOW DEPRECIATION WORKS

The depreciation system is designed to allow businesses and investors to divide capital assets into specific categories and then to claim depreciation as allowed under current federal tax law. The legal definition reads: “Depreciation is the annual deduction allowed to recover the cost or other basis of business or investment property having a useful life substantially beyond the tax year.”1

REAL ESTATE DEPRECIATION

Real estate investments cannot be deducted as an expense in the year you buy property. However, building improvements (the building itself, as well as a new roof and siding, fixtures, additions, and repairs of internal systems) are set up as capital assets and depreciated over many years. You also claim depreciation for an auto or truck and other equipment needed to manage your real estate investments, including computers, office equipment, and landscaping equipment.

Depreciation applies to all capital assets, with one exception. You are not allowed to claim depreciation for the value of land. For example, if you buy an investment property for $150,000, and the land is worth $40,000, you can deduct depreciation on the improvements of $110,000. The value of the land portion of your investment property—in this example, $40,000—is carried on your books as an asset and cannot be deducted or depreciated.

Depreciation is always calculated based on your purchase price and never on current market value. Let’s say you bought your primary residence fifteen years ago and paid $85,000 ($15,000 for land and $70,000 for improvements). If you later decide to convert this property to a rental, your depreciation will be based on the $70,000 base value of improvements. Even if values have increased significantly and the property is now worth $200,000, your depreciation has to be based on your purchase price. This is one of the flaws in the tax and accounting rules. Current valuation does not matter. Only your original cost can be used to set depreciation.

The calculation is based on the recovery period to be used. Residential real estate is normally depreciated over 27.5 years using the straight-line method (the same amount is depreciated each year). After 27.5 years, the property is fully depreciated, and no more depreciation will be allowed. Each year’s depreciation is reported as an expense, and this is where real estate investors have an advantage over most other forms of investment. Depreciation is a legitimate expense even though you do not have to spend money each year. It’s calculated based on what you paid for the property, and the expense is deductible on your tax return. This is set up as a journal entry and entered into your books. The journal entry is necessary because no cash is exchanged. An example based on annual depreciation of $2,550 is summarized in Table 8-1.

TABLE 8-1. DEPRECIATION JOURNAL ENTRY ($)

Accumulated depreciation is a reduction of the asset. So, as this is entered each year, the net asset value declines as the expense is recorded to reduce net investment income.

AMORTIZATION

Closely related to depreciation is amortization. You are allowed to amortize some assets, such as points paid on mortgage loans or the cost of starting a business, and intangible assets.

For most real estate investors, amortization expense will be limited to points charged by a lender. The points paid to acquire your mortgage loan cannot be deducted in a single year. Instead, those points are amortized over the number of years of the loan. For example, if your mortgage loan is set up to be repaid over thirty years and you paid $1,500 in points, you are required to amortize it at a rate of $50 per year.

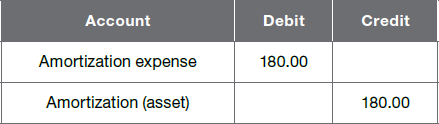

A point is equal to 1 percent of the amount borrowed and there are two types. Origination points are assessed to compensate the loan originator, and discount points are a form of prepaid interest. For primary residence loans, these are fully deductible as itemized deductions, with limitations for higher earners. However, for income property, the points have to be set up as assets and amortized over the term of the loan. For example, if you borrow $180,000 and are charged three points, the total is $5,400. You are allowed to amortize only a portion each year. For a thirty-year loan, this is $180 per year. The journal entry to record this expense is shown in Table 8-2.

TABLE 8-2. AMORTIZATION EXPENSE JOURNAL ENTRY ($)

ASSETS USED ONLY FOR INVESTMENT PURPOSES

For all assets you use exclusively for investment purposes, calculating depreciation is not complex, especially compared to the calculation for property used partly as a residence and partly as a rental. As long as you have a solid bookkeeping system and records of the dates you purchased assets, you can claim depreciation as a legitimate expense. A distinction should be made between when a capital asset is purchased and when it is placed in service. You are allowed to depreciate an investment asset from the date it is placed in service, meaning the date you began using it as part of your investment program. The distinction is further clarified by the IRS: “Depreciation starts when you first use the property in your business or for the production of income.”2

![]()

EXAMPLE: You planned to begin purchasing investment properties last year, and you bought a riding lawn mower to be used exclusively in maintaining your properties. However, you did not buy your first property until last month. Even though the lawn mower was purchased last year, it was not placed in service until you bought your first rental property.

![]()

![]()

EXAMPLE: You bought a house three months ago as a rental. In your city, there is a large university population. You did not rent it out immediately because you expected higher demand once the fall semester began. In this case, depreciation begins once you begin seeking tenants, not on the purchase date.

![]()

MIXED USE OF AN ASSET

One difficulty in calculating depreciation arises when you use an asset—a truck, for example—partly for personal use and partly for investment. In that case, you are required to keep records to establish the applicable investment use. The depreciation you claim is reduced to the percentage of investment use, and you are not allowed to claim depreciation above that level.

Part-time rental of property or renting out a portion of your house also presents special considerations when it comes to depreciation. Calculating depreciation on mixed-use property is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

ESTABLISHING AN OFFICE AT HOME

You may use a portion of your home to conduct business for managing your real estate investments. The rules are strict for claiming a depreciation deduction in this case. You have to be able to establish that you use a specific room 100 percent of the time to conduct business. For example, if you use a room as an office, you cannot also use it to store personal items or as a guest room. It has to be assigned exclusively to investment activity. The amount of depreciation claimed would be a percentage of your home’s total value (excluding land). For example, a 300-square-foot room in a 2,500-square-foot home is equal to 12 percent of the total. You could claim one-twelfth of the allowable annual depreciation, if you were able to establish the exclusive investment use of that room.

IS IT WORTH IT? Most investors find that even if they can establish an exclusive use of one room as an office, the amount of depreciation is so small that it is not worthwhile to claim depreciation. For example, if your home’s value (excluding land) is $125,000, the total annual allowance (based on the 27.5 years you are required to use for depreciation) is $4,545 per year, and one-twelfth of that is $379. Tax advisers have observed that claiming expenses for a home office may act as a red flag and could even trigger an audit. Considering the relatively small benefit to this claim, it is of questionable value. In addition, because overall net losses on investment activity are limited, you might not need this additional deduction.

CLAIMING DEPRECIATION

To report and claim depreciation, you will need IRS Form 4562 and the publication entitled “Instructions for Form 4562.” Detailed explanations for filling out forms are included in Chapter 10.

WHERE TO LOOK IRS forms and publications can be downloaded online from the Internal Revenue Service’s Web site at https://www.irs.gov.

In submitting your tax return, you are not required to provide detailed information about the assets involved. However, you need to keep permanent records in your files of (a) asset purchases and sales, including date and amount, (b) methods you use to calculate depreciation each year, and (c) calculations for depreciating assets that apply only partially to investment activity.

Because depreciation rules may change from one year to the next, it is wise to calculate depreciation at the time you begin claiming it—usually when you buy the property—and set up a summary for the entire period involved, keeping that calculation as part of your bookkeeping records. This also helps you to complete your tax return each year and to adjust for new purchases or for the sale of assets during the year. Later in this chapter, several tables are provided summarizing the percentages of depreciation allowed under specific recovery periods and using various depreciation methods. Once you identify the correct method to use, you will be able to calculate depreciation for the initial year as well as for all future years for each asset.

KEEPING THE LOSS LIMIT IN MIND

The limitation of the $25,000 maximum annual deduction of real estate losses is critical to planning how to depreciate assets. (See Chapter 9 for tax rules relating to real estate investing.)

![]()

EXAMPLE 1: Your adjusted gross income (AGI) last year was $85,000. You are entitled to claim up to a full $25,000 loss from real estate activities qualified under current IRS rules.

![]()

![]()

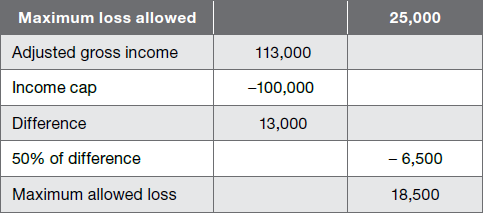

EXAMPLE 2: Your adjusted gross income last year was $113,000. Your maximum deductible loss from real estate is reduced by 50 cents for each dollar of income above $100,000. Accordingly, your maximum allowable loss deduction is $18,500, summarized in Table 8-3.

![]()

TABLE 8-3. MAXIMUM LOSS DEDUCTION ($)

The deduction for real estate losses is reduced to zero for adjusted gross income of $150,000 or more. The “adjusted gross income” used in the previous calculation is actually a modified version of the number reported; certain expenses have to be added back in to arrive at the total to be used (see Chapter 9).

Some assets you use in real estate activity can be depreciated using accelerated methods, where more depreciation is claimed in the early years and less later on. You can elect to use the straight-line method for those assets (more about this method later in this chapter). The point is an important one: There is no advantage in claiming an accelerated amount of depreciation, even when it is allowed under the rules (such as for vehicles, computer and office equipment, and landscaping tools), if you will not be allowed to claim a loss. If you have a lot of depreciation expense during the year, it is of no value if the loss is disallowed. This occurs if your reported loss is more than $25,000 or if your modified adjusted gross income is higher than $150,000. In these instances—with your deductible losses limited anyway—it makes sense to report depreciation over a longer period of time and minimize the amount claimed each year.

CALCULATING LAND VALUES

The one exception to the general rule that you can depreciate capital assets is land. You are not allowed to depreciate land under any circumstances. This raises a question for anyone who purchases investment property: How do you calculate the value of land versus the value of improvements?

CONSISTENCY

You can use any reasonable method to calculate land value. However, once you pick a method, it is a good idea to apply it consistently to all properties. As long as you can justify your calculation on some logical basis, you will be able to claim depreciation for improvements and exclude the value of land. You should select a method that you believe is most advantageous to you and use it for all properties. Because annual loss deductions are limited, “advantageous” could mean using the method with the highest land value. However, if your income is below $100,000, and your real estate expenses are fairly low, you may want maximum depreciation deductions. In that case, select a method that reflects the lowest portion of total value for land.

THREE COMMONLY USED METHODS

Here are three accepted methods for calculating land value. Notice that each one results in a quite different number:

1. Assessed Value. Your county assesses property for the purpose of calculating annual property taxes. Assessed value may approximate current market value, or it could be far lower than the realistic levels. Calculating land value based on the assessed value is simple; the property tax bill sent to you by your county shows the breakdown.

![]()

EXAMPLE 1: You purchased a property this year and paid $137,500. Your assessed value, according to your tax bill, is $90,000. This consists of $22,000 (24 percent) for land and $68,000 (76 percent) for improvements. The division is applied to your purchase price of $137,500. You would assign land a value of $33,000 ($137,500 × 0.24), while improvements, subject to annual depreciation, would be valued at $104,500 ($137,500 × 0.76).

![]()

2. Appraised Value. At the time you purchase property, it is appraised for financing and also to determine whether the purchase price is reasonable. You can use the breakdown in the appraisal report to divide land from improvements.

![]()

EXAMPLE 2: You purchased a property for $137,500. The appraisal ordered by your lender came in at $140,000 and identified land as being worth $45,000 (32 percent) and the replacement value of your home at $95,000 (68 percent). Using appraisal value to calculate value, you would calculate the value of land as $44,000 ($137,500 × 0.32) and the value of depreciable improvements at $93,500 ($137,500 × 0.68).

![]()

3. Insurance Value. You also have values assigned in your real estate insurance policy. Most policies include calculations of dwelling protection plus “other structures” protection (as well as other values). You can use these values as the basis for determining your depreciable base.

![]()

EXAMPLE 3: You purchased a property for $137,500. Based on location, age of the home, and features, your insurance company assigns a value of $80,000 to the dwelling and an additional $8,000 for the storage shed and detached garage. Total depreciable base using this method is $88,000, with the remaining $49,500 assigned to the value of land. You do not pay insurance for land, since its value would remain even if your property were lost in a fire or other damage.

![]()

DETERMINING WHICH METHOD TO USE

Each method uses a different base, and any one of them can be justified. The appraised value in Example 2 was closest to what was actually paid for the property. This will not always be the case, and it will not always be the most advantageous method to use.

If you have only one rental property, low expenses, and income below $100,000 per year, you will probably benefit by claiming as much depreciation as you are allowed, so a calculation that gives less value to land and more to improvements is preferable. However, if you have several properties—meaning higher overall reported losses due to more depreciation claimed—you will not be able to claim all of the allowed depreciation, and part of it will be deferred to later years. If your adjusted gross income is more than $100,000, your allowable annual deduction is going to be reduced as well, so claiming more depreciation has no benefit.

![]()

KEY POINT Selecting a method to value land is a matter of planning ahead. It should be based on your personal income, the number of properties you own for investment purposes, and your need for the deduction.

REPORTING A TAX LOSS

For the purpose of argument, let’s assume that you will be reporting a tax loss on your properties. This is more likely when the depreciable portion of your investment property is relatively high. For example, in comparing two investments costing $150,000 each, depreciation will be higher when the land value is small, and it will decline for a second property whose land value is much higher.

If you own a single property and want the highest possible deduction, you will do better (in terms of the deduction and after-tax cash flow) if you select properties with a low portion of land value. However, you may also own several properties, in which case you cannot use a higher deduction. In that case, you may prefer to buy properties whose land value represents a higher portion of the total investment value. In such a situation, the property may gain higher-than-average market value, especially if the land value is high because of its location. So you need to balance the desirability of depreciation deductions (or lack of need for those deductions) against the long-term investment value of the land itself.

Depreciation often creates a net loss even in situations where cash flow is positive or breakeven. This occurs because the investment is structured so that rental income covers payments and expenses, but there is little or nothing left over each month. When you then calculate depreciation, it creates a net loss. If you are able to write off $5,000 a year in depreciation on each property, once you reach five rentals, you have arrived at the maximum, so any further deductions will be of no value. Since the annual loss deduction applies, no matter how many properties you own, it makes sense to plan ahead with the loss ceiling in mind.

The $25,000 maximum applies to married couples. The law anticipated investors filing separately to increase their maximum loss, so the ceiling is even lower if you are married and filing separately. As long as you live apart from your spouse for the entire year, you are allowed to deduct only $12,500, and the deduction begins to phase out at 50 cents per dollar of income above $50,000. For example, if you are legally separated and living in an apartment by yourself, and your spouse is living in your primary residence for the entire year, then the deduction will be allowed—but the maximum loss and income ceilings are cut by one-half, so real estate investors cannot take advantage of the rules by proceeding as two single persons, each one claiming a $25,000 loss. Thus, if you are married, filing separately but you and your spouse did not live apart for the entire year, the loss on real estate investments is not available at all. The restriction is intended to discourage tax planning that uses marriage to increase deductions or to avoid a reduction in those losses during the year.

HOW TO DEPRECIATE PARTIALLY USED ASSETS

Many investors employ capital assets that also serve partially as personal property. For example, a car or truck, landscaping equipment, or a computer system may be used for personal reasons as well as for managing your real estate investments. In these situations, you need to keep careful records to establish the exact degree of nonpersonal use. Only by being able to document how assets are used will you be entitled to claim a depreciation deduction. For example:

![]() Automobiles. If you have used your car to monitor properties, meet with prospective tenants, collect rents, meet with your accountant, and other investment-related purposes, that is considered investment use. Keep a log of investment mileage showing the date, purpose of the trip, and total mileage. A sample automobile log is available in Chapter 6.

Automobiles. If you have used your car to monitor properties, meet with prospective tenants, collect rents, meet with your accountant, and other investment-related purposes, that is considered investment use. Keep a log of investment mileage showing the date, purpose of the trip, and total mileage. A sample automobile log is available in Chapter 6.

The investment usage is next divided by total miles. For example, if you drove 3,415 miles to manage your real estate investments, and total mileage for the year was 22,660, investment usage would be 15 percent (3,415 ÷ 22,660). In this example, you would calculate full-year depreciation and then claim 15 percent of the total as an investment expense. (There are special depreciation limits on cars, trucks, and vans, which are explained later in a separate section of this chapter.)

![]() Computers. In the case of computer systems, you would calculate investment usage based on an approximation of the amount of time used on investment-related matters (record keeping or online housing market research, for example). The actual time spent is the standard for this calculation, not the time the computer was available for use.

Computers. In the case of computer systems, you would calculate investment usage based on an approximation of the amount of time used on investment-related matters (record keeping or online housing market research, for example). The actual time spent is the standard for this calculation, not the time the computer was available for use.

![]() Landscaping Equipment. If you use personal assets such as lawn mowers to care for rental properties, you have to calculate a basis for depreciation. If you maintain the grounds of two properties, you could probably justify deducting two-thirds of the basis as investment expense (the remaining one-third would apply to your own residence and thus would be nondeductible personal use).

Landscaping Equipment. If you use personal assets such as lawn mowers to care for rental properties, you have to calculate a basis for depreciation. If you maintain the grounds of two properties, you could probably justify deducting two-thirds of the basis as investment expense (the remaining one-third would apply to your own residence and thus would be nondeductible personal use).

![]() Property Converted During the Year. For the purpose of calculating depreciation on property that was converted to an investment property during the year (or an investment property converted to your primary residence), the percentage should be based on the number of months it was used for each purpose. For example, if the property was a rental for three months and your primary residence for nine months, you are entitled to claim 25 percent of the full-year depreciation as an investment expense.

Property Converted During the Year. For the purpose of calculating depreciation on property that was converted to an investment property during the year (or an investment property converted to your primary residence), the percentage should be based on the number of months it was used for each purpose. For example, if the property was a rental for three months and your primary residence for nine months, you are entitled to claim 25 percent of the full-year depreciation as an investment expense.

![]() Renting Out Part of Your Home. If you rent out part of your primary residence, the depreciation should be calculated based on a breakdown of square footage. For example, if your house contains 2,200 square feet and you rent out 600 square feet, 27 percent counts as a rental, and you can claim 27 percent of the full-year depreciation. This calculation becomes more complex when it is a room rental and a tenant also has access to the kitchen and common areas of the property. In that situation, you must modify the calculation on a basis that makes sense. For example, if the common areas (e.g., kitchen, living room, and bathroom) constitute approximately 50 percent of the total living space, a portion of that space could be deductible if available to a tenant. So, if four people live in the house, you could justify claiming an additional deduction for a tenant’s access to common areas. Using all of the assumptions in this example, the calculation is shown in Table 8-4.

Renting Out Part of Your Home. If you rent out part of your primary residence, the depreciation should be calculated based on a breakdown of square footage. For example, if your house contains 2,200 square feet and you rent out 600 square feet, 27 percent counts as a rental, and you can claim 27 percent of the full-year depreciation. This calculation becomes more complex when it is a room rental and a tenant also has access to the kitchen and common areas of the property. In that situation, you must modify the calculation on a basis that makes sense. For example, if the common areas (e.g., kitchen, living room, and bathroom) constitute approximately 50 percent of the total living space, a portion of that space could be deductible if available to a tenant. So, if four people live in the house, you could justify claiming an additional deduction for a tenant’s access to common areas. Using all of the assumptions in this example, the calculation is shown in Table 8-4.

TABLE 8-4. SQUARE FOOTAGE CALCULATION.

Total square feet |

2,200 |

Rental square feet |

27% × 2,200 = 594 |

Common area in square feet |

1,100 |

Number of people living in the house |

4 |

Number of tenants living in the house |

1 (25% of total) |

Equivalent square footage value for tenant access |

25% × 1,100 = 275 |

Rental square feet, rounded to 600 |

600 + 275 = 875 |

Percentage of total |

875 ÷ 2,200 = 40% |

This calculation would allow you to claim 40 percent of the full-year depreciation as rental expense. If the rental is available for only part of the year, the percentage has to be further reduced to the applicable number of months.

FAIR CALCULATION OF THE ASSET’S USE

Any asset used partially for investment purposes should be depreciated based on a fair calculation of the portion of use. Each asset has to be calculated in its own manner, since the attributes of each (e.g., automobile, telephone, computer, and lawn mower) are different. There is no one method, so you need to keep good records of how you break down the investment portion and how you calculate depreciation for each asset.

DEPRECIATION LIMITS ON CARS, TRUCKS, AND VANS

The depreciation you claim for passenger automobiles used for investment purposes is limited, even if you use the auto exclusively for business. The IRS publishes annual limits. For example, passenger automobiles placed in service during the year 2016 are subject to the maximum depreciation limitations shown in Table 8-5.

TABLE 8-5. 2016 AUTO DEDUCTION LIMITS ($).

Year |

Limits |

1 |

3,160 |

2 |

5,100 |

3 |

3,050 |

4 onward |

1,875 |

Note that these are limits for depreciation that you are allowed to claim if the auto is used 100 percent for investment. If you use it only partially for investment, you have to reduce the limits accordingly. For example, on the basis of your auto log, if your total investment use was 15 percent, you placed the automobile into service in late 2016, and the auto has been in use for two years, the maximum allowable would be adjusted not only for the partial business use but also because it applied for only part of the year.

IMPORTANT For current information about the limits for the depreciation deduction for automobiles, trucks, or vans placed into service after 2003, refer to the updated edition of the IRS publication “Instructions for Form 4562.”

CLASSIFICATION LIVES AND RECOVERY PERIODS

All assets are classified in one of several classifications. Some of these so-called recovery periods are highly specialized, and others are more generalized. The recovery periods that apply to real estate investments are summarized in Table 8-6.

Classification |

Assets |

5-year property |

Autos and light trucks; office and computer equipment; appliances; carpets; furniture |

27.5-year property |

Residential real estate |

39-year property |

Nonresidential real estate |

Most capital assets used in your rental activity will fall into the five-year classification; your residential real estate investments belong in the 27.5-year recovery period. The calculation of depreciation under each recovery period is determined by the tax rules.

FIVE-YEAR RECOVERY PERIOD

The five-year recovery period depreciation is accelerated in the early years and reverts then to straight-line depreciation. The acceleration is at the rate of 200 percent. This means that the initial depreciation allowance is twice the amount that would be allowed using the straight-line method. (Under the straight-line method, the same deduction is allowed each year.) Depreciation in the five-year recovery period, using the General Depreciation System guidelines, is shown in Table 8-7.

TABLE 8-7, DEPRECIATION RATES PER YEAR.

Year |

Depreciation (%) |

1 |

20.00 |

2 |

32.00 |

3 |

19.20 |

4 |

11.52 |

5 |

11.52 |

6 |

5.76 |

THE HALF-YEAR CONVENTION

Under the straight-line method, the five-year depreciation term would allow 20 percent per year. Since the 200 percent accelerated depreciation applies, it would seem that the first year’s depreciation should be 40 percent; however, it is only 20 percent. The reason for this disparity is that five-year property is calculated using what is called the half-year convention. Under this convention, all property placed into service during a specific year is treated as though it were placed in service at the midpoint of the year. Thus, only one-half of the applicable depreciation is allowed in the first year.

This rule makes it easier to calculate depreciation for all assets in the first year of service. Since the rate of depreciation allowed is 200 percent of the straight-line rate, the annual depreciation declines. For example, under the straight-line rate, you would claim 20 percent per year for five years. Using 200 percent declining balance, the first year is 40 percent (reduced to 20 percent, due to the half-year convention). Therefore, if the asset were worth $1,000, you would depreciate $200 the first year. That leaves $800. The second-year calculation would be for 200 percent of a five-year rate:

($800 ÷ 5 years) = $160

Under the 200 percent method, the $160 is doubled, so you would write off $320. This is twice the straight-line rate based on the $800, which works out to 32 percent of the original $1,000 cost of the asset. Applying this same declining calculation to each remaining year’s balance, the depreciation declines rapidly in these first years. The rate reverts to the straight-line method, according to the depreciation schedule.

EXCEPTION If property placed in service during the last quarter of the year is higher than 40 percent of the total of all assets placed in service for the year in that same recovery class, the midquarter convention is used in place of the midyear convention. For example, you purchased a total of $4,000 during the year that is depreciated under the five-year recovery period. But $1,700—more than 40 percent—was purchased in the fourth quarter. So you would use the midquarter convention. Under this method, the percentage of depreciation allowed is changed from 50 percent (the half-year standard) to 87.75 percent for assets placed in service during the first quarter, 62.5 percent for the second quarter, 37.5 percent for the third quarter, and 12.5 percent for the fourth quarter.

CALCULATING DEPRECIATION FOR REAL PROPERTY

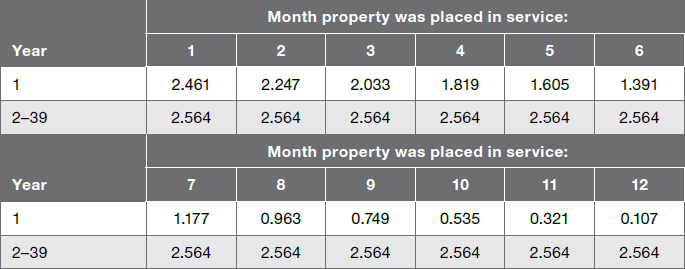

The rules are different for real property. In calculating first-year depreciation for residential or nonresidential real property, the midmonth convention is used for calculating depreciation during the first year. The first-year percentage varies depending on the month the property is placed in service.

RESIDENTIAL PROPERTY

For residential property, which is depreciated over 27.5 years under the General Depreciation System, you are required to use the straight-line method, so the value of real property (purchase price excluding land) is calculated by dividing the total by 27.5. But the actual amount of depreciation you claim each year depends on the month the property is placed in service. Table 8-8 demonstrates that for the first seventeen years, the depreciation expense varies and that from the eighteenth year onward, the depreciation expense reverts to a uniform percentage. That is 3.637 percent, the equivalent annual allowance based on 27.5 years.

In the application of the midmonth convention, the calculation varies only during the first year. In the second year through the ninth year, the annual calculation is identical. And the annual deduction increases by only one-half of 1 percent per year after that. This is summarized in Table 8-8.

TABLE 8-8. DEPRECIATION SCHEDULE, 27.5-YEAR RECOVERY PROPERTY (%)

![]()

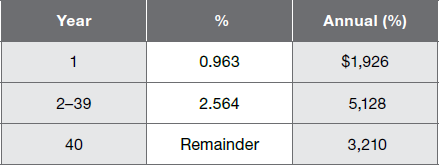

EXAMPLE: You acquired your residential investment property in August this past year. The value of property (excluding land) is calculated at $125,000. Your depreciation, based on Table 8-8 and using the midmonth convention, will be as shown in Table 8-9.

![]()

TABLE 8-9. DEPRECIATION SUMMARY

According to the midmonth convention table, the yearly depreciation from years 10 through 28 alternates back and forth between 3.636 percent and 3.637 percent. In the example given, this will make a difference of only a dollar per year. In the interest of simplicity, it is practical to continue depreciating $4,545 per year and claim the remaining balance in the twenty-ninth year.

COMMERCIAL OR INDUSTRIAL PROPERTY

The schedule for nonresidential real estate is less complicated. The full term of thirty-nine years is broken down under the midmonth convention as shown in Table 8-10.

TABLE 8-10. DEPRECIATION SCHEDULE, 39-YEAR RECOVERY PROPERTY (%)

For example, if the value of a commercial or industrial investment property (excluding land) was calculated at $200,000, and you acquired the property in August (the eighth month of the year), your allowable depreciation deduction each year would be calculated, using Table 8-10 and the mid-month convention, as shown in Table 8-11.

TABLE 8-11. DEPRECIATION SUMMARY

![]()

KEY POINT While the special calculations for half-year and midmonth conventions complicate these calculations, they apply for the most part only to the first year. They help to make the depreciation rules fair and consistent. For example, it would not be equitable to allow the same level of depreciation for a $200,000 real property acquired in December as allowed for one acquired in January, nearly a full year earlier.

KEEPING RECORDS OF DEPRECIATION CALCULATIONS

Keeping track of the depreciation you are allowed to deduct each year is not difficult. It makes sense to calculate the depreciation for each year at the beginning (when you put the asset in service) and to then maintain the schedule so that you do not have to recalculate the deduction each year.

This suggestion is especially useful for the accelerated five-year recovery period, in which the deduction changes each year. You may have a long list of assets in this classification. Beyond your computer and automobile, you could also have dozens of appliances, for example, each acquired in a different year; so keeping track of depreciation allowed for the full term of ownership is a sensible idea.

![]()

EXAMPLE: You have five rental properties. Each one contains a stove, refrigerator, and dishwasher. Four also have washers and dryers. Altogether, you own twenty-three appliances. If these were acquired in different years, calculating depreciation could be complicated.

![]()

SIMPLIFYING THE CALCULATIONS

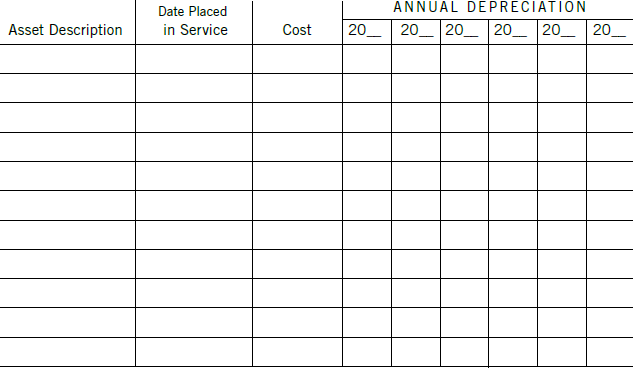

Set up a schedule like the one shown in Figure 8-1 to track annual depreciation in the five-year recovery period. (You can use the same schedule for your real property, but if the calculated deduction is identical in the second year and onward, it is not necessary to include them on the schedule.)

In filling out this schedule, you want to keep track of two separate calculations: the annual depreciation and total to date. This is necessary because, in reporting depreciation on your tax return, you are required to show both prior depreciation and current depreciation. Therefore, allow two lines per asset.

![]()

EXAMPLE: You acquired a washer/dryer and a refrigerator for Property 1 and a refrigerator for Property 2 during the past year. Using the half-year convention, the form for these acquisitions would be completed as shown in Figure 8-2.

![]()

REPORTING DEPRECIATION FOR EACH ASSET

This example provides you with the information needed to report depreciation—both current year and prior depreciation—for each asset acquired during the year through the entire term that depreciation will apply. This type of schedule can be set up using Excel or a similar spreadsheet program and extended indefinitely. Subtotals can also be calculated automatically and entered for each year, for the cost as well as for current-year depreciation and prior depreciation. (In using a spreadsheet program, placing current year and prior year subtotals in separate columns makes the calculation of subtotals easier.)

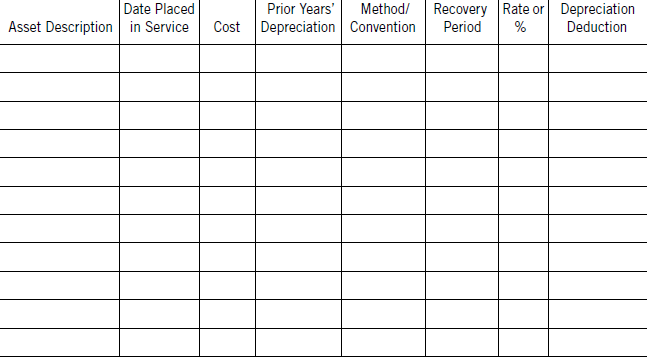

TRACKING TOTAL ANNUAL DEPRECIATION

An annual worksheet is also useful for keeping track of each year’s claimed depreciation. This worksheet can be used as part of your permanent records, or it can be attached to your tax return as a supplementary schedule. The worksheet is designed to report all assets, listed and subtotaled by property; the date placed in service; cost; prior years’ depreciation; method and convention; recovery period; rate or percentage; and the depreciation deduction. A worksheet that provides all of this information is shown in Figure 8-3.

The information gathered in your permanent records and recorded is easily transferred to this worksheet. For example, the details entered in the example shown in Figure 8-3 provide all of the information needed to complete the depreciation portion of your tax return.

MAKING DEPRECIATION ELECTIONS

If you want to calculate depreciation on a different method than the prescribed ones, you can make a tax election. There are two elections you are likely to use, both of which reduce your depreciation expense in the earlier years but increase the expense in later years. If you anticipate reaching the $25,000 maximum deduction this year and you don’t need the extra expense, you may elect to slow down the rate of depreciation. Or, if your adjusted gross income exceeds $100,000, it means your real estate investment losses are limited, so claiming depreciation does not help. Again, you may elect to depreciate under an alternate method.

A few points to remember about tax elections:

![]() They are usually irrevocable. Once you elect to use a slower depreciation rate, you cannot simply revert to the prescribed method.

They are usually irrevocable. Once you elect to use a slower depreciation rate, you cannot simply revert to the prescribed method.

![]() The election has to be made in the first year. You need to decide how to depreciate capital assets during the first year you report the asset as being placed into service.

The election has to be made in the first year. You need to decide how to depreciate capital assets during the first year you report the asset as being placed into service.

![]() The election usually applies to all assets in the same recovery period. Most elections have to be applied to all assets in the recovery class that are placed into service during the same year.

The election usually applies to all assets in the same recovery period. Most elections have to be applied to all assets in the recovery class that are placed into service during the same year.

![]() The election must be made no later than the due date of your tax return. The deadline is the due date for the year the assets were placed in service, including extensions of time to file.

The election must be made no later than the due date of your tax return. The deadline is the due date for the year the assets were placed in service, including extensions of time to file.

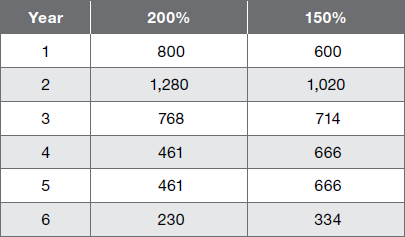

TAX ELECTION #1: 150 PERCENT DECLINING BALANCE

The calculation of depreciation under the 150 percent schedule is made according to the percentages given in Table 8-12.

![]()

EXAMPLE: You acquired five-year property this year worth $4,000. You are considering making an irrevocable election to use the 150 percent declining-balance method rather than the 200 percent method because you believe that you may benefit more from deferring the expense until later. Each of these methods would produce the annual depreciation expenses summarized in Table 8-12.

![]()

TABLE 8-12. COMPARING 200% AND 150% DEPRECIATION ($)

Expressed on a percentage basis, the 150% method calls for the breakdown by year shown in Table 8-13.

TABLE 8-13. DEPRECIATION SCHEDULE, 5-YEAR RECOVERY PROPERTY, 150%

Year |

Percent |

1 |

15.00 |

2 |

25.50 |

3 |

17.85 |

4 |

16.66 |

5 |

16.66 |

6 |

8.33 |

Given that the asset value in this example is limited to only $4,000, the difference is not significant. However, the higher the dollar amount of assets placed into service, the greater the effect of deferring part of the depreciation into the later years.

TAX ELECTION #2: STRAIGHT-LINE DEPRECIATION

Another election is to apply straight-line depreciation each year. It is irrevocable and has to be applied to all property in the same recovery period and placed into service during the year. For example, $4,000 of five-year property would be depreciated at the rate of 20 percent per year. Since the half-year convention still applies, the first and sixth year would see $400 in depreciation expense, and the second through fifth years would have $800 each.

IMPORTANT Depreciation is not difficult to calculate, but the rules are revised from time to time. Keeping track of the current rules can be difficult, so you need to refer to the instructions any time you acquire new assets as part of your real estate investments.

RECAPTURE OF DEPRECIATION UPON SALE

When you sell your investment assets, you are required to “recapture” the depreciated value. This means that you will be taxed on the amount of depreciation that you claimed during the period you owned the property.

![]()

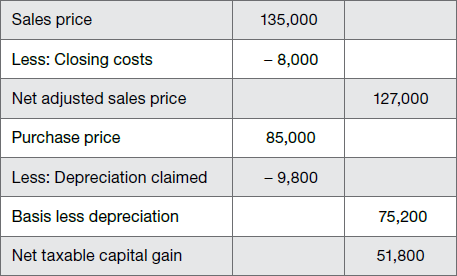

EXAMPLE: You purchased a rental residential property five years ago and paid $85,000. The value assigned to the land was $25,000 and the value of the improvements to the property was $60,000. Last year, you sold the property for $135,000, and you had closing costs of $8,000. Your net proceeds were $127,000.

![]()

In this example, your profit on the investment was $42,000 (net sales price of $127,000 less purchase price of $85,000). However, your capital gain will be adjusted to recapture depreciation. You claimed depreciation using the 27.5-year recovery period, which amounted to about $9,800. (This figure will vary depending on the month you purchased the property.) The calculation of your capital gain would be as shown in Table 8-14.

TABLE 8-14. ADJUSTED NET CAPITAL GAIN ($)

KEEPING COMPLETE RECORDS

Considering the complexities of the depreciation rules—as well as rules for calculating net capital gains—many investors require the help of a qualified tax preparer. Your task may be limited to documenting all of your transactions and maintaining records to ensure that you will be able to establish all that you are entitled to claim. A system’s effectiveness can be best judged by how easily someone else can figure out what is taking place. Your accountant or tax preparer will have an easier job to do if you keep good records of purchase dates, dollar amounts, depreciation calculations, and all other transactions.

The importance of thorough records becomes clear when you consider the tax rules that cover real estate investing. Depreciation is not the only complex topic. The next chapter explains how the rules apply to your investments.