9.

UNDERSTANDING THE TAX RULES FOR REAL ESTATE

Everyone who pays taxes knows that the rules seem to change continually and that forms, record-keeping requirements, and calculations can all be complex. In addition to having to contend with the same tax rules as everyone else, real estate investors have to be aware of some rules that apply just to them.

The good news is that most of these special rules are beneficial to real estate investors. For example, a sweeping tax reform in 1986 did away with the majority of tax shelters. Before that date, investors could deduct losses without specific limitations and were able to avoid taxes altogether in some instances. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 established new rules. Since that date, any loss on a passive investment—one in which other people manage your investment property for you or make the day-to-day decisions—can no longer be deducted. Such losses have to be carried forward and applied against future passive gains. The one exception to this reform was real estate investing. Unlike other investors with passive losses, real estate investors can deduct passive losses.

PASSIVE AND ACTIVE INCOME

By definition, passive activity is an investment that simply provides income or loss to you. If you do not “materially participate” in running an operation, it is a passive activity. For real estate investors, this distinction is not difficult to make. If you invest by buying units in a limited partnership, it is a passive activity. As a limited partner, you do not participate in selecting properties, maintaining them, and making decisions from one day to the next. The general partners take care of those activities, and limited partners are provided passive gain or loss for their investment.

ACTIVE PARTICIPATION

If you purchase a house and rent it out, selecting tenants yourself, setting rental amounts, performing maintenance work (or hiring someone to do it for you), and deciding which properties to buy or sell, then you are actively participating in the investment. Even if you hire a manager to run the properties, as long as you are involved in tenant selection, maintenance and other decisions, you are actively involved in the property. So, even though real estate investing (by way of direct ownership of properties) is a passive activity, you are allowed to claim a deduction for losses if you materially participate in operating the investment properties.

MATERIAL PARTICIPATION

To qualify for the “material participation” rule, you have to own at least 10 percent of the property. So if you buy investments with a family member or friend, you have to be able to demonstrate that you are at least a 10 percent owner and that you materially participated in managing the investments.

These rules prevent the creation of tax write-offs for individuals who need the deductions but do not really take part. For example, a parent whose income consists of dividends, interest, and Social Security may not need the deductions from investment properties or has excess levels of losses, and a son or daughter who is earning a salary but has little or no deductions may benefit from a tax loss. In this situation, the ownership and participation have to be bona fide to be allowed. A family cannot simply assign a portion of ownership to a member who needs the deductions.

EXCESS LOSS

Any unused excess loss is carried forward and applied to future years, or, when you sell property, the loss is applied against the capital gain. If you have several properties, you can apply the entire passive loss carryover to offset the gain, even though those losses are not specifically incurred on the sold property. If the passive loss carryover exceeds the gain on property, you can deduct the entire loss that applies to that property.

![]()

KEY POINT Carrying excess losses forward is not beneficial in many instances. Deductions from one year to the next are fully deductible up to the $25,000 limit. However, if losses are eventually deducted from profits and long-term capital gains are realized, you only benefit one-half of the dollar value, since the long-term rate is calculated on only 50 percent of the net gain.

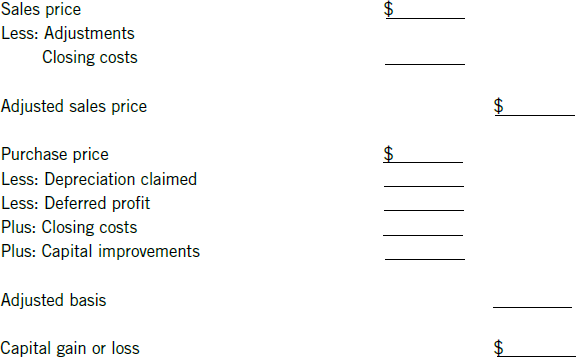

ADJUSTED GROSS INCOME

The definition of adjusted gross income (AGI) has to be modified for this calculation. Normally, adjusted gross is all reported income, minus student loan interest, IRA investments, moving expenses, one-half of self-employment tax, and alimony, for example. In calculating adjusted gross income for computation of maximum real estate deductions, you cannot include IRA contributions, any taxable Social Security benefits, interest on student loans, deductions for one-half of self-employment tax, or tuition and fees deductions. In other words, most of the popular adjustments to adjusted gross income are disallowed.

![]()

EXAMPLE: Your adjusted gross income last year was $87,500. This included deductions for IRA contributions, student loan interest, and tuition deduction totaling $22,000. You also had net losses from real estate investments of $27,000. If the modified adjusted gross income was less than $100,000, you would be allowed to deduct $25,000 in real estate investment losses, and the excess of $2,000 would be carried over and applied to future years. However, your adjusted gross income has to be modified for the $22,000 in adjustments that are disallowed as well. This alters your AGI for this purpose to $109,500. Your maximum real estate deduction is reduced by one-half of the excess over $100,000. The computation is as shown in Table 9-1.

![]()

TABLE 9-1. MAXIMUM LOSS DEDUCTION

In this example, you would have to carry forward the excess loss of $6,750 ($27,000 minus $20,250) to use in future years. You calculate the maximum deductible losses and carry-forward on Form 8582 (Passive Activity Loss Limitations), which becomes a part of your tax return (see Chapter 10).

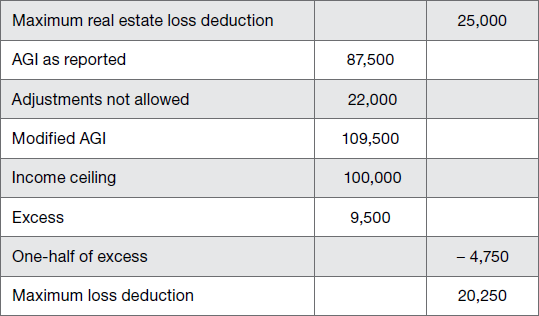

RULES FOR THE SALE OF REAL ESTATE

When investment real estate is sold, the net proceeds are treated as a capital gain or loss. The transaction is listed on Form 4797, where depreciable property is reported. Calculation of the gain itself and of the taxable portion involves adjustments to both purchase and sales price.

LONG-TERM CAPITAL GAINS

Qualified long-term capital gains are taxed at a special rate below the usual tax rate, so you benefit from favorable tax treatment for property held longer than twelve months. The calculation of taxable gain or loss includes closing costs at the point of purchase and sale, additional capital improvements made while you owned the property, recapture of depreciation, and adjustments in the basis of the property if you deferred a gain on investment property previously.

Deferred gain works in this way: If you own a rental property and you sell it reporting a gain, you can defer that gain if you replace the investment property with a similar property that costs as much or more, within a specified period of time. (This exchange rule is explained in more detail later in this chapter.)

![]()

EXAMPLE: You purchased a rental property for $135,000 and, a few years later, sold it for an adjusted price of $160,000. You had a gain of $25,000 and you met the rules for deferring the gain. The profit of $25,000 is carried over, and the basis in the new property is reduced by that amount. You purchased a new property for $175,000 for use as a rental. With the deferred gain from the first property, your adjusted basis is reduced to $150,000.

A worksheet for calculating net gain or loss on investment property is shown in Figure 9-1.

![]()

SELLING YOUR PRIMARY RESIDENCE

The rules for selling your primary residence are different. A married couple can exclude up to $500,000 of gain from the sale of their house, and a single person can exclude $250,000. You are required to use your home as your primary residence for at least two years during the five years prior to sale, and you cannot claim this exemption more than once during a two-year period. Beyond that, the exemption of gain can be claimed as many times as possible.

The profit or loss on your real estate investments is separate from the reporting of gain on a primary residence. However, the special exclusion of tax on gain for your residence raises an interesting planning point. You can avoid or defer taxes on capital gains from real estate investing in one of two ways. First, you can execute a “like-kind” exchange, buying a new investment property upon the sale of an older one (see “Like-Kind Exchanges” later in this chapter). Second, you can convert a rental property to your primary residence. In this case, you would need to meet the two-year rule and would still have to pay taxes for the recapture of all depreciation claimed.

CONVERTING A RENTAL PROPERTY

When you convert, it simply means that you move into the house you have been using as a rental and live there for at least two years before selling it. If you then have a gain upon sale, the only portion that would be taxed would be depreciation recapture. Of course, this requires considerable advance planning. You have to put in the two-year period as primary residence over a five-year term. For example, let’s say that you have been living in your current house for at least two years. If you convert it to a rental for the next three years and then sell it, you will be able to claim the primary residence exclusion—as long as you did not sell another property within two years and make a similar claim.

SOME TAX RULES TO NOTE

The depreciation recapture cannot be avoided, even upon conversion from rental to primary residence. You are always required to pay capital gains tax upon sale of any property for which a depreciation expense has been claimed.

Similarly, you have to pay taxes on any deferred gain, even if a rental property is later converted to a primary residence. For example, if you bought a rental property for $125,000 and later sold it for $150,000, you could defer the $25,000 profit by going through a like-kind exchange. However, if you later converted the new property to your primary residence and then sold it, you would have to divide the profit into two segments. The first segment is the taxable portion, consisting of the deferred gain and depreciation recapture; the second segment is the remaining profit that is qualified for exclusion under the primary residence rule. (This includes the requirement that you use the property at least two years during the five-year period before the sale and the limitation that you have not claimed the exemption on another property within the last two years.)

IMPORTANCE OF TIMING

This limitation—that you can claim the residential exemption only once in a two-year period—has to be kept in mind when you are timing your decisions to sell property, especially when it is property used as a primary residence or that has been converted.

![]()

EXAMPLE: You own two properties. The first one was your primary residence until thirty months ago, at which time you converted it to a rental. The second is your current primary residence, which you purchased thirty months ago. You have decided to sell your properties and move from the area, so both properties are placed on the market.

![]()

Which property should you claim? In this example, both properties would qualify for the exemption of gain because you lived in each as a primary residence for at least two years over the past five years. However, you can claim only one property within a two-year period. So it would be wise to claim the exemption for the property with the higher capital gain in order to reduce your tax burden. The only other choice would be to defer selling your current primary residence for two years, so that you would be able to avoid taxes on that property as well. By converting it to a rental and waiting two years, you would still qualify for the two-year/five-year rule and could exempt all gain, except depreciation recapture.

You could not make the same move on the property you converted thirty months ago. By waiting the two years, you would no longer meet the requirement that you used it as a primary residence for at least two out of the last five years. You have lived in your present primary residence for thirty months; an additional twenty-four months would take the total up to fifty-four months, during which time the property was not a primary residence. That leaves only six months during the last five years, disqualifying it for the two-year/five-year restriction.

Does conversion make practical sense? Converting property from an investment to a primary residence is a wise tax-saving move, as long as it also makes practical sense. However, you may not view a rental property as meeting your requirements for a primary residence, so it may be impractical to move your family into a property that is simply not suitable. You may also be unwilling to wait two full years before selling the property. Investors often need to cash out as soon as possible, which is one of the most common reasons for wanting to sell an investment property. Considering the personal preferences for your primary residence and your need for cash, it may not make sense to convert rental property just to avoid capital gains taxes.

How do you establish a primary residence when you convert a property? This is a record-keeping and documentation problem that has to be thought through. Your mailing address is usually your primary residence, although many people use post office boxes or mail drops instead of receiving mail at their homes. You can establish primary residence by keeping copies of paid utility bills, subscriptions, and other mail showing that you were present at the property. You use your primary residence address in most cases when you file your income tax return. Your employer also keeps records of your primary residence to mail out tax information forms at the end of the year. Once you begin thinking about it, establishing the location of your primary residence, as well as the dates you lived there, is not difficult.

LIKE-KIND EXCHANGES

As a real estate investor, you can defer taxes on gains from property indefinitely, as long as you invest proceeds in properties that are equal or greater in value, and as long as you reinvest within 180 days from the sale date. That means a subsequent purchase has to be closed within that period. The tax deferral of gain from investment property is known as a 1031 exchange (named after IRC Code Section 1031).

This election is more commonly called a like-kind exchange because qualified property has to be of the same type. If you have one rental and you exchange it for another, that is like-kind property. You can trade a house for a duplex or apartment or switch between residential and commercial, but as long as it remains rental property, the gain can be deferred. You can even exchange improved property for raw land, or vice versa, and have it qualify as a like-kind exchange. The one exception regarding real estate is that both properties in the exchange have to be within the United States. Foreign properties do not qualify.

WHERE TO LOOK RS Publication 544, “Sales and Other Dispositions of Assets,” includes the specific rules for 1031 exchanges. It can be downloaded from the Internal Revenue Service’s Web site at https://www.irs.gov/publications/p544.

SPECIFIC RULES FOR THE EXCHANGE

The rules to qualify for the exchange are specific. When you sell one property, you are required to identify and complete the purchase of another property within 180 days from sale. As part of this timing requirement, you need to identify property you intend to purchase as a like-kind exchange within forty-five days from sale; this is known as the identification period. Because of this requirement, it may be necessary to identify more than one potential property, so that if a sale falls through, you will not be precluded from completing a 1031 exchange.

HIRING A QUALIFIED INTERMEDIARY

You cannot execute a like-kind exchange yourself. You need to hire a facilitator, or a “qualified intermediary,” to complete the paperwork and to act as go-between for both sides of the transaction (you as exchanger and the seller of the new property). Even though you have to pay a facilitator for the services, it is a wise idea. You want to ensure that the like-kind exchange is not disallowed because you didn’t file in time or provide the proper notification. For example, when you make a written offer on a property, you need to include a statement advising the seller that you are purchasing the property as part of a 1031 exchange, and the seller needs to agree to cooperate in that exchange. A facilitator can help in phrasing this notification properly, as well as in making sure all deadlines are met.

The facilitator is necessary in the transaction because you, as seller, are not allowed to receive money or property before the transfer has been completed. The facilitator has to take legal title to the new property and then transfer it to you, or else the deferral will not be allowed. The facilitator enters into a written agreement with you specifying the terms and conditions of the exchange; therefore, the individual cannot be related to you. Furthermore, the facilitator cannot have been an employee, accountant, attorney, or broker working for you for at least two years before the transaction.

WHEN TO ELECT THE 1031 EXCHANGE

The 1031 exchange is a useful election when you want to continue investing in real estate and when you want to upgrade from one property to another. For example, if you have one or more single-family houses and you want to exchange them for a single apartment house, a 1031 exchange can be executed so that all of your profits are deferred. Electing the 1031 exchange does not mean you escape liability for the taxes, only that the tax is put off until you sell the exchanged property.

The timing limitation of 180 days can be a problem when you are trying to sell several properties. Unless your local market is very strong, you may have a problem disposing of several properties within that relatively short window. You may require the help of a skilled real estate agent, working in cooperation with your 1031 exchange facilitator, to ensure that you meet your deadlines.

If you want to dispose of a rental property but you do not want to invest in another, a 1031 exchange makes no sense because it keeps you tied into the market. One exception is when you don’t want to sell because you need the money but you want to defer the taxes. You can exchange a rental property for raw land and qualify for the exchange. Because it will have no tenants, raw land is low maintenance. You must pay property taxes, of course, but you could defer taxes on your profit by trading out of a rental situation.

The alternative discussed previously—turning investment property into your primary residence—is easier to execute and also may help you to avoid taxes. Unlike the 1031 exchange, in which taxes are merely deferred, the transfer from investment property to primary residence allows you to sell tax free for the entire profit, except depreciation recapture and any previously deferred gain.

WATCH THIS In any matters involving tax avoidance or deferral, you should consult with an expert tax adviser before making any decisions. An error in timing, filing the wrong form, or not being aware of changes in the rules can all cause expensive tax consequences. Because tax rules change from time to time, you need to make sure that the rules in effect when this book was published continue in effect when you are making decisions about your property.

RULES FOR PROPERTIES USED PARTLY AS RENTALS

When your primary residence is partially rented out, you must break down the tax deductions between personal expense and rental expense. This rule applies when (a) you rent out a portion of your home or (b) the property is a rental for part of the year and your primary residence for the remainder.

When you use your primary residence in this manner, you need to keep good records to document your calculation of the division of expenses. The portion assigned to personal use includes mortgage interest and property taxes. The portion assigned to rental use includes deductions for depreciation, utilities, mortgage interest, and property taxes, plus any other rental expense. However, you can deduct only the portion of those expenses that applies to the rental.

![]()

EXAMPLE: You rented out a room in your home for nine months last year. The size of the area rented out was 900 square feet, and the total square footage of your house is 3,100. By this calculation, 29 percent of expenses can be deducted. This includes 29 percent of the full-year depreciation, utilities, property taxes and mortgage interest, and all other expenses that apply to the rental. (If you advertise the rental, for example, you can deduct 100 percent of the cost of advertising, since it applies solely to rental investment and not to personal use.)

![]()

In this example, 29 percent of property taxes and mortgage interest are listed as rental expense; therefore, the remaining 71 percent would be listed as itemized deductions. If your deductions are marginal between itemizing and claiming a standard deduction, this calculation could result in tax savings. For example, if the standard deduction is higher than the total of your calculated itemized deductions (after deducting the portion applicable to rental), then your taxes will be lower by claiming the standard deduction instead of itemizing your deductions.

LESS THAN CLEAR-CUT DIVISION OF USE

The precise calculation of rental division is relatively easy when you rent out an in-law unit with its own kitchen and bath. However, when you rent out a room and allow a tenant access to your kitchen, living room, bathroom, laundry room, and other areas, you need to arrive at a reasonable calculation of the rental portion of total expenses.

Several possible methods of calculation are worth exploring. These include:

![]() Number of People Living in the Home. This calculation assumes that all people residing in the home make about the same degree of use of common areas: kitchen, living room, and bathroom. It has two parts. First, you calculate the rented square feet as a percentage of total square feet; second, you calculate the percentage of people renting (versus total residents) and apply that to the remaining square feet.

Number of People Living in the Home. This calculation assumes that all people residing in the home make about the same degree of use of common areas: kitchen, living room, and bathroom. It has two parts. First, you calculate the rented square feet as a percentage of total square feet; second, you calculate the percentage of people renting (versus total residents) and apply that to the remaining square feet.

![]()

EXAMPLE: Your home has 3,100 square feet and you rent out a room of 900 square feet. Your family contains four people, so a total of five people live in the home. Your common areas (those areas accessible to all household members) are calculated at 1,050 square feet. The calculation of the percentage that applies to rents is:

1 ÷ 5 = 20% (the percentage of people renting)

1,050 × 20% = 210 (square feet of common areas shared with the renter)

900 + 210 = 1,110 (total square feet assigned to rental)

1,110 ÷ 3,100 = 36% (percentage of shared-space expenses that apply to renter)

![]()

In this example, you are allowed to deduct 36 percent of interest, property taxes, insurance, utilities, and depreciation as rental expenses; the remaining 64 percent of interest and property taxes are listed as itemized deductions.

![]() Rental Income as a Percentage of Mortgage Payment. An alternative method for making the calculation is to treat rental income as a percentage of your total mortgage payment. In this example, let’s assume that the rental income you receive each month is $400, and your total mortgage payment is $1,314. In this case, 30 percent would be the applicable percentage of expenses you would be allowed to deduct against rental income.

Rental Income as a Percentage of Mortgage Payment. An alternative method for making the calculation is to treat rental income as a percentage of your total mortgage payment. In this example, let’s assume that the rental income you receive each month is $400, and your total mortgage payment is $1,314. In this case, 30 percent would be the applicable percentage of expenses you would be allowed to deduct against rental income.

![]() Rent Charged as a Percentage of Overall Market Rent. A third method is to calculate the fair market rent for a house such as yours. For example, in your city, the typical four-bedroom, two-bath home may rent for $1,200 per month. Since you are collecting $400 in rent, it is reasonable to assume that the applicable percentage of deductions is 33 percent, or one-third of the fair market rent you could collect if you rented out the entire house.

Rent Charged as a Percentage of Overall Market Rent. A third method is to calculate the fair market rent for a house such as yours. For example, in your city, the typical four-bedroom, two-bath home may rent for $1,200 per month. Since you are collecting $400 in rent, it is reasonable to assume that the applicable percentage of deductions is 33 percent, or one-third of the fair market rent you could collect if you rented out the entire house.

WHERE TO LOOK Check IRS Publication 527 to study rules concerning mixed-use residential rental property. This publication can be downloaded from the IRS’s Web site at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p527.pdf.

As long as you apply a method consistently from one year to the next to calculate rental expenses, you can use the one that yields the most advantageous outcome. In the earlier example, breaking down the square footage provided the most advantage because you can deduct the largest percentage (36 percent) of total expenses as rental expenses. The higher the percentage assigned to rental activity, the higher your deductible expenses. You cannot deduct anything beyond interest and property taxes as part of your itemized deductions. Therefore, it is advantageous to assign a larger percentage to rental activity, as long as your assumptions are fair and supportable. And if you end up using the standard deduction instead of itemizing as a result of assigning a higher portion of interest and taxes to the rental portion, your taxes will be lower.

As far as interest and property taxes are concerned, you are allowed to deduct the entire amount regardless of how much is assigned to personal use and how much to rental investment. The difference in how much you pay in taxes is the result of the percentage of other expenses you can deduct.

STATE TAX LIABILITIES

The rules for state income taxes vary considerably. Treatment of real estate income, expenses, depreciation, and deductibility of losses depends on current state law. Even tax rates on the state level are inconsistent.

A few states assess no income tax. The remaining states impose either a flat rate or a graduating rate. Each state’s tax requirements are different because of state-level economics and legislative policy.

WHAT TO DO To determine the impact of real estate rental activity on your state income tax rates, check with your state’s tax agency or with your tax adviser. Tax forms for each state can be downloaded on several Web sites, including the Tax Foundation at http://taxfoundation.org/article/state-individual-income-tax-rates-and-brackets-2016.

If a particular state imposes rules that are different from the federal rules for the treatment of losses, you will need to recalculate your deductions and taxable income. Some states further require you to include a copy of your federal tax return with the state return that you file and to reconcile any differences in reported income and deductions. This extra burden makes the record-keeping rules more difficult for you as a real estate investor.

You may also need to recalculate depreciation that you claim on your real estate investments. A state does not necessarily adopt the federal depreciation rules for the purpose of calculating state taxes. Therefore, it may be necessary to keep two different records of depreciation, one each for federal and state calculations. When you eventually sell an investment property, the taxable gain will be different because of these inconsistencies.

![]()

KEY POINT In assessing the tax benefits of real estate investment, the state implications have to be reviewed carefully. Federal rules allow deductions of passive activities and tax-deferred exchanges of investment property (and tax-free sale of primary residence), all as incentives for real estate investors. The states do not automatically provide the same benefits.

The tax rules for real estate are complex and include many special provisions. Consult with a tax adviser for tax planning, especially if you have high income from non–real estate investments, wages, or self-employment. The many questions concerning how to position yourself to reduce taxes legally are complicated when you add in the state tax issues. The state rules do not always conform to the federal rules, so elections you make this year could have an effect on both federal and state liabilities. This is where the help of an expert can be useful; you want to follow all of the rules, reduce your overall taxes within the law, and ensure that you have not missed any potential deductions.