CHAPTER 6

BUILDING GUIDANCE IN SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING

Perhaps your most important design decisions involve the amount and type of guidance you provide in your scenario-based e-learning environment. Research tells us that pure discovery learning does not work. “Instructional programs evaluated over the past fifty years consistently point to the ineffectiveness of pure discovery” (Mayer, 2004, p. 17). Learning environments that lack guidance fail to manage what I call the flounder factor. Learners engage in unproductive trial-by-error explorations. The results are at best inefficient learning and, at worst, no learning and/or learner dropout. In this chapter I review some common techniques you can use to build a guided discovery (versus a discovery) learning environment through use of guidance techniques, also known as scaffolding.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

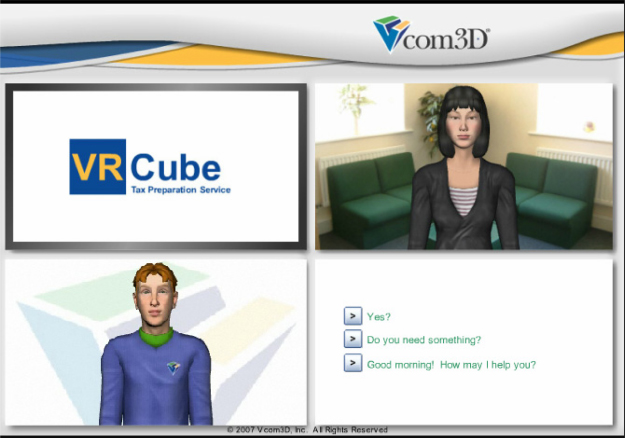

Compare Figures 6.1 and 6.2. Based on what you can see in these screen shots, answer the questions that follow. You can see my answers at the end of the chapter.

FIGURE 6.2. An Automotive Troubleshooting Scenario-Based e-Lesson.

With permission from Raytheon Professional Services.

WHAT IS GUIDANCE?

Typically, we classify overt sources of help such as online coaches or feedback as guidance. However, I use the term guidance—also called scaffolding—to designate any element in a scenario-based e-learning design that minimizes the flounder factor. In other words, any design element that converts discovery learning into guided discovery is a form of guidance. For example, an interface that offers a choice of only one response option at a time (such as Figure 6.1) is more “guided” or constrained than an open-ended environment that allows higher levels of learner control.

In this chapter I will summarize nine different design techniques you can use for guidance. These techniques don’t span all possible options. However, they will give you a rich menu of the most common support techniques that you can adapt to your own context. Which techniques you select will depend on your target audience—primarily their topic-relevant prior knowledge and your outcome goals. For Question 3 under What Do You Think?, I would select options A and B as the most important factors. Regarding target audience, novice learners will need much higher levels of guidance compared to apprentice workers. Some learning domains, such as diagnosis and repair, focus on process goals for which the desired outcome is a solution and also the process the learner uses to derive the solution. For example, in Figure 6.2 the learner has a choice of various tests, and only if the learner is given an environment in which she can select among multiple testing options and testing sequences, can that process be practiced and refined. However, offering a higher level of learner control also imposes a less structured environment. In other situations such as many compliance goals, the outcome may be more limited, for example, a yes or no decision calling for only two or three response options. In Table 6.1 I summarize nine guidance options to be described in this chapter. Feel free to peruse these techniques and dive into those most relevant to your context.

TABLE 6.1. Techniques for Guidance in Scenario-Based e-Learning

| Technique | Description | Example |

| Faded Support | Initial scenarios offer more guidance than later scenarios. | The first scenario solution is a demonstration followed by a scenario that is partially worked out for the learner. |

| Simple to Complex Scenarios | Each module includes a progression of simple to more complex scenarios. Complexity can come from the number of variables in the scenario, the amount of conflict in case data, or from unanticipated events. | Straightforward failure scenario resolvable with five tests in initial troubleshooting followed by more complex scenario requiring eight tests. |

| Open vs. Closed Response Options | On-screen response options range from limited-choice responses to open-ended responses. | A multiple-choice response option in a branched scenario is more closed than a multiple-select response option, which in turn is more closed than a role play. |

| Interface/Navigation Options | Branched scenario designs offer fewer options at one time compared to full-screen displays. Menu titles can reflect the recommended work flow. |

Figure 6.1 compared to Figure 6.2. In bank loan scenario (see Figures 5.1, 5.2), the tabs are labeled: introduction, data, analysis, facility structure price, and recommendations. |

| Training Wheels | Constrain the interface to allow only partial functionality. For example, some on-screen elements (visuals or menu items) remain inactive for a given problem or until a given state in problem solution. | The automotive shop allows only limited functionality in the beginning. Some tool options respond with “do not use for this problem” when selected. |

| Coaching and Advisors | A virtual helper that often takes the form of an on-screen agent that offers hints or feedback. As lessons progress, agent help is reduced. | In Bridezilla the coach comments on each choice made during the interview process. In later lessons, the agent comments only when selected. |

| Worksheets | For complex decisions that rely on collection and analysis of multiple data sources, a worksheet stores data and guides the analysis. | In an underwriting scenario, a series of worksheets is used to help learners assemble and analyze client data. |

| Feedback | Knowledge of results given either as the learners progress or at the end of the scenario is an essential source of guidance. | In Bridezilla the coach comments on each choice made during the interview process. In addition, the attitude meter shows client feelings based on questions asked. |

| Collaboration | Opportunities to collaborate during scenario solution with experts or other learners via synchronous or asynchronous methods supports learning. | In Bridezilla the learner can e-mail some of the expert advisors with questions not addressed in the lesson. |

OPTION 1: FADE SUPPORT FROM HIGH TO LOW

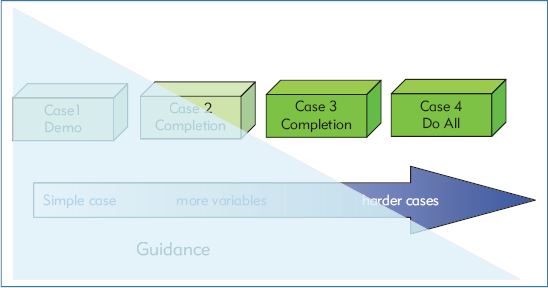

Let’s begin with a general principle for the imposition and fading of learner guidance. In Figure 6.3 I illustrate the concept of faded support. In this model, the support consists of a three-part progression starting with a solution demonstration followed by two partial assignments and ending with a full problem assignment.

FIGURE 6.3. Fade Support and Increase Complexity as Scenarios Progress.

So in a simple situation, imagine that for one class of scenarios—for example, overcoming objections—your first case would be relatively simple and would be viewed by the learner as a demonstration in which the on-screen expert describes how an objection was handled. Figure 6.4 from a pharmaceutical sales course, uses a video to demonstrate an expert performance. To encourage engagement in the demonstration, we added questions next to the example. The next scenario would be a bit more complex—perhaps involving more variables or a prescriber who is already happy with a competitor’s product. This scenario would be partially demonstrated and the learner would finish it. The final scenario would involve a complex situation requiring the learner to resolve the entire case. Initial cases might use a more structured branched scenario response format, whereas later cases might require a role-played response in a virtual classroom or face-to-face setting.

FIGURE 6.4. Following a Video Example of Responding to Objections, Questions Are Used to Promote Engagement with the Example.

For this illustration I used a fading technique of evolving from demonstration to full problem assignment. However, the basic principle—to offer higher levels of support on initial cases and gradually remove it in later scenarios—can apply to any of the guidance techniques to follow.

OPTION 2: MOVE FROM SIMPLE TO COMPLEX

This technique is also illustrated in Figure 6.3. As an experienced instructional professional, you are familiar with developing practice exercises or case studies that range from simple to complex. Similar strategies apply here. Scenario complexity may be determined by several factors, depending on your learning domain. For example, a simple case may have fewer variables and more clear-cut correct and incorrect responses. Alternatively, a simple case may have as many variables as a more complex case, but the more complex case offers conflicting variables or unanticipated obstacles that surface mid-stream. Typically, each course module will incorporate several scenarios that focus on a cross-section of the tasks. For example, in a pharmaceutical selling course you might find the following modules: (A.) Selling to a family practice; (B.) Selling to a specialty practice; and (C.) Selling to an HMO. Within each module you will include three or four scenarios, each incorporating the major selling stages, such as “assess client needs,” “present relevant product features,” “answer questions,” “respond to objections,” and “set the stage for the next visit.” Within each module the scenarios will range from simple to complex.

Use SMES to Identify Complexity Factors

To derive factors that contribute to case complexity, ask your subject-matter expert team members to individually write three situations they have faced in a particular class of scenarios, ranging from simple to more complex. For each situation, they should write enough detail so that the setting, obstacles, and their solution actions and rationale are clear. Next assemble your team of experts to share their simple, moderate, and complex scenarios and agree on the classifications. Guide the experts to use their examples as a basis to derive the key factors that make a scenario simple or complex. You can then reverse engineer your process, using the complexity factors and samples to build cases at an appropriate level.

For example, if you were developing scenario-based e-learning on presenting a new drug to a specialty group practice, you might ask your top sales performers to independently write out simple, moderate, and complex situations in which they effectively worked with such a practice. Consider giving your experts a template as well as a model example to ensure that you receive sufficient detail. For example, provide a completed table with headers for relevant information such as the drugs involved, a brief profile of the practice and prescribers, the main presentation points, the objection(s) raised, the objection response techniques, and a summary of the outcomes.

OPTION 3: CONSIDER OPEN VS. CLOSED RESPONSE OPTIONS

In Chapter 4, I reviewed the different types of outcome deliverables your learning goals may dictate, as well as how to translate those deliverables into on-screen responses, including multiple choice, multiple select, fill-in, drag and drop, and click on-screen objects. In addition, I discussed options for outcome deliverables that require open-ended responses such as shared media pages, breakout rooms, spreadsheets, PowerPoint slides, Word documents, role plays, etc. For novice learners, you may design scenarios with frequent limited response choices and clear-cut right versus wrong answers. For example, in the branched scenario course shown in Figure 6.1, each screen offers three response options, which in turn trigger immediate audio feedback from the on-screen agent. Alternatively, for more experienced learners, you may offer a multiple-choice screen with many options, such as that shown in Figure 6.5, requiring the learner to select one correct answer from a list of ten or more alternatives. As a general guideline, offer fewer response options such as multiple choice for more novice learners and more complex response options, including multiple select, fill in, drag and drop, shared media pages or role plays, for more experienced learners.

FIGURE 6.5. A Multiple-Choice Response Screen in Automotive Troubleshooting Lessons with Many Solution Options.

With permission from Raytheon Professional Services.

OPTION 4: CONSIDER INTERFACE/NAVIGATION DESIGN

The branched scenario design as shown in Figure 6.1 is a more straightforward response template in the form of multiple-choice options with immediate feedback on each screen. In contrast, for more advanced learners and when your goal is not only an “answer” but also the data-gathering and analysis process, a menu or whole-screen design offers the potential for less constrained responses. Menu or whole-screen navigational layouts provide multiple paths for progressing through the lesson and may be essential if your goal is to teach a problem-solving flow as well as analysis decisions. As a general guideline, the more response alternatives available in the interface, the more unguided the learning environment. A classroom role play or project assignment offers the most unguided environment in which the learner can construct free-form responses.

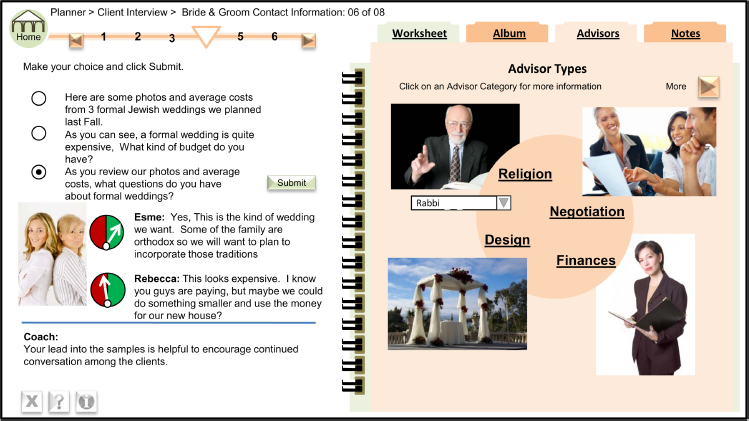

A menu design such as that used in the bridal consultant course offers an intermediate level of structure. You can use menu links to lead to guidance resources, as shown in Figure 6.6. Alternatively, you can use menu links to reflect the workflow, as shown in the bank underwriting training in Figures 5.1 and 5.2. The learner can choose to access any of the menu options, but the options themselves provide a structure to the environment. In a blended learning environment, you may start with a multimedia introductory lesson using a branched scenario design and later evolve to more open-ended responses in an instructor-led setting.

FIGURE 6.6. The Album and Advisor Tabs (Upper Right) Link to Guidance in the Bridezilla Lesson.

OPTION 5: ADD TRAINING WHEELS

Before my grandsons could really ride their bikes, they spent several months riding with training wheels. The training wheels gave them enough freedom to learn balance maneuvers but also prevented ugly spills. In more open interfaces such as the automotive shop, you can add training wheels by constraining the response options. For example, at the start of the automotive troubleshooting scenario, when the learner mouses over the various testing objects, the car is the only active object, as indicated by a halo effect and a callout. Verifying the fault is the first step in the troubleshooting process and is the only response allowed in the beginning of the scenario.

As another source of training wheels in the virtual automotive shop, when the learner selects certain testing equipment that is irrelevant to the scenario, a text message sates: “This test is inappropriate at this time.” At one extreme, you could disable every test object on the screen, only enabling each as it is appropriate to a given testing stage. At the other extreme, you could enable every object, allowing the learner to make multiple incorrect or inefficient decisions. You may decide on a progressive approach using a more constrained environment in initial scenarios that open gradually as learning progresses. My point is that training wheels that are inherent in the limited options of a typical branched scenario design can also be imposed in a whole-screen design by selective activation of the on-screen objects.

OPTION 6: INCORPORATE COACHING AND ADVISORS

Coaching requires providing brief context-specific guidance or direction at the moment of need. For example, if the learner is not following a recommended path or if the learner would like more support, an advisor could appear (push approach) or could be accessed (pull approach) to give hints and/or links to more detailed support. Coaching guidance may come from an avatar represented as a persistent on-screen guide, as shown in lower left section of Figure 6.1, or from a pop-up text box. Whatever the form, the coaching message should be short and specific to an on-screen action recently taken by the learner. Branched scenario designs could provide a coaching message with each response taken. Open designs may offer less frequent guidance, only appearing when learners deviate significantly from recommended paths.

Does it matter whether the coach takes the form of a person, a cartoon, or some other representation? Research comparing different representations, including cartoon figures, video of a person, or no figure at all, found that the actual representation did not make a great deal of difference to learning (Clark & Mayer, 2011). There is some evidence that whatever figure you decide to use (animated or still—nonhuman or human), incorporating some human embodiment features in the form of eye movement and hand gestures promotes learning.

The voice quality is important. For example, learning was better from an avatar using a native-speaker-friendly voice than one with a machine-generated or foreign-accented voice. We need more research on avatar representations, but you are probably okay with whatever you select as long as the avatar serves a relevant instructional role such as coaching or giving feedback, the voice is natural and friendly, the language is personal, and there is some human embodiment such as eye glances and gestures. You may want to test your graphic approach with your target audience. For example, among different job roles you may find different reactions to a cartoon avatar.

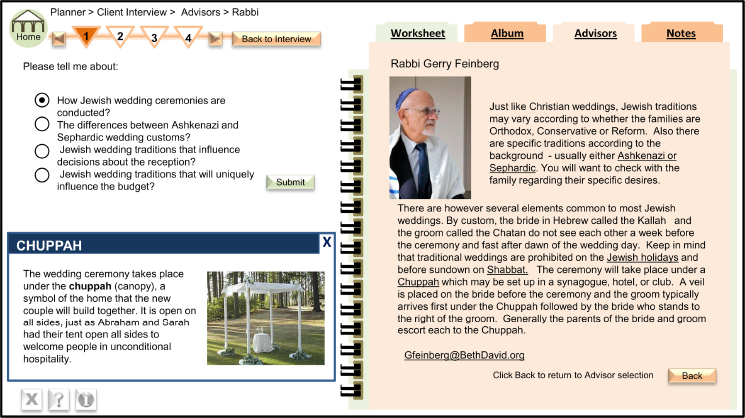

Advisors can be used to offer perspectives on one or more facets of a scenario. In Table 6.2 I list some alternative advisors you might consider for the eight scenario domains. As shown in Figure 6.6, when the learner clicks on the advisors tab in the Bridezilla case, a screen appears with four visuals representing clergy, design, negotiation, and finances. Each of these in turn leads to specialist advisors such as a rabbi, priest, minister, or imam. As illustrated in Figure 6.7, upon selecting a specific resource such as Rabbi Feinberg, questions on the left side of the screen serve as menus to access unique expertise of that advisor.

TABLE 6.2. Potential Advisors for Each Learning Domain

| Domain | Potential Advisors |

| Interpersonal | Manager, top performer, expert negotiator, virtual clients, product expert |

| Compliance | Manager, colleague, human resources representative, legal representative, government agency official |

| Diagnosis and Repair | Tech support, journeyman performer, product engineer, quality assurance, diagnostic expert |

| Research, Analysis, Rationale | Critical thinking expert, senior performer, resource expert, manager |

| Tradeoffs | Various perspectives relevant to decisions to be made, such as client feedback, financial, legal, ethical, religious |

| Operational Decisions | Equipment engineer, quality assurance, lead technician, senior operator |

| Design | Expert designer, previous clients, quality assurance, project manager, accountant |

| Team Collaboration | Project manager, senior performer, senior leadership, accountant, communication expert, team members |

FIGURE 6.7. Selecting a Specific Advisor (See Figure 6.6) Leads to Topic-Specific Information.

In an online course for nurses on fetal alcohol syndrome, links led to emails of real advisors, including a public health nurse and a guardian for a child with fetal alcohol syndrome. These advisors had volunteered for the duration of the course to offer their experience. If your organization has established social networks of experts, perhaps their expertise could be leveraged as an instructional resource. Note in Figure 6.7 a link to the Rabbi’s email for additional questions.

OPTION 7: EMBED WORKSHEETS

A worksheet is a template in which learners can select or input intermediate products as they progress through a scenario. Worksheets offer structure by focusing the learner on specific intermediate data or decisions. They can also offer memory support as repositories for data as it is accessed. For complex decision-making processes, your organization may already provide various tools to guide the workflow, as well as for memory support and decision making. Use the same tools in your learning environment. Alternatively, you may have to design some tools that may then later extend into the actual workplace as performance support. In Figure 5.3 you can review the worksheet used by the wedding consultant during the client interview.

OPTION 8: ADJUST FEEDBACK

One of the most powerful instructional strategies for any kind of training is feedback. In fact I devote a full chapter to feedback in scenario-based learning in Chapter 8. Here I mention feedback specifically as a guidance resource. Feedback offered with each decision, as in the customer service branched scenario shown in Figure 6.1, provides more immediate guidance than feedback that is withheld until the learner has progressed through a number of intermediate stages to reach a solution, such as in the automotive troubleshooting scenario.

In Chapter 3 I distinguished between traditional instructional feedback and consequential feedback that I call intrinsic feedback. For more guidance, consider using both instructional feedback and intrinsic feedback. Intrinsic feedback will show consequences of actions and decisions but may not provide sufficient rationale to guide learners. See Chapter 8 for more details on the what, when, and how of feedback in scenario-based e-learning designs.

OPTION 9: MAKE LEARNING COLLABORATIVE

Collaboration during problem solving offers a popular and potentially helpful source of guidance. Research has shown that, when producing a novel product or solving a problem, a collaborative effort yields better results than solo work (Clark & Mayer, 2011). Kirschner, Pass, Kirschner, and Janssen (2011) report that collaboration is most effective when scenarios are challenging. In contrast, learning from easier scenarios was best when tackled by individual learners. Collaboration imposes additional mental load, and if a scenario is already relatively easy, the extra load will not add much instructional value.

Consider using structured argumentation as a proven collaborative technique. In structured argumentation, teams of two are given a position or facet of a problem to research. After a research period, each team presents their position or product to another team working on a different position or facet of the problem. Teams reverse roles, and when all presentations are completed, teams merge and create a combined product that synthesizes all perspectives. Structured argumentation is well applied to tradeoff scenarios in which the goal is not so much a solution per se but rather an understanding of diverse perspectives on the scenario.

Social media offer multiple opportunities for virtual collaboration through breakout rooms, shared media pages, and wikis, among others. A combination of synchronous and asynchronous collaboration might offer the best option. Synchronous team activities such as virtual or face-to-face breakout sessions have proven effective for brainstorming multiple solutions. Asynchronous team activities work well to give everyone time for reflection. Whatever forms of collaboration you decide on, in general you should keep team sizes small enough to promote optimal engagement and consider techniques to motivate equal participation. For more details on collaboration, see Chapter 13 in Clark and Mayer (2011).

WHAT DO YOU THINK? REVISITED

In my introduction to this chapter, I suggested that you compare Figures 6.1 and 6.2 and respond to the questions below:

Here are my thoughts. The branched scenario customer service lesson shown in Figure 6.1 offers more guidance because response options are limited to a single choice among three options and the on-screen coach provides immediate feedback. In contrast, the whole screen virtual shop offers more choices and feedback is not available until after a number of decisions are made. However, even in the automotive shop, some guidance is provided by inactivating some of the objects and by responding with “don’t go there” advice when some tools are selected. Therefore, while the branched scenario design does impose more guidance, a whole-screen design can also manage the flounder factor by limiting response options.

I selected all of the options for Question 2. The customer service lesson is much less complex due to limited choices on each screen, immediate feedback from the coach, as well as response options that lack nuance. For Question 3, I would select Options A and B. Learners with more prior knowledge and outcomes that focus not only on correct answers but also on problem-solving processes may be better served by interfaces with more choices such as a menu or whole-screen layout.

COMING NEXT

Now that you have considered the guidance you plan to provide, a closely related design issue relates to instructional resources. The goal of scenario-based e-learning environments is learning. Therefore, instructional resources are usually an essential element of your design. In the next chapter I will review some common options, including tutorials, examples, and reference resources.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Kirschner, F., Paas, F., Kirschner, P.A., & Janssen, J. (2011). Differential effects of problem-solving demands on individual and collaborative learning outcomes. Learning and Instruction, 21, 587–599.

A helpful research-based review of situations in which collaboration is and is not effective.

Mayer, R.E. (2004). Should there be a three-strikes rule against pure discovery learning: The case for guided methods of instruction. American Psychologist, 59, 14–19.

A classic review and discussion of the shortfalls of discovery learning.