CHAPTER 1

WHAT IS SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING?

Imagine Corey, an apprentice automotive technician. He’s had basic training in the fundamentals. He’s completed a year on the job. Still, when an unusual work order shows up, he can’t help feeling a little uneasy. He sees the confidence and efficiency of the journeymen technicians and wishes he could get there faster. . . .

Next consider the situation of a new combat officer. He’s been on several deployments, but this is his first time in charge of the entire company in a combat situation. He looks forward to the challenge but also realizes that he will be making life-and-death decisions. Everyone has to start somewhere, he thinks. But he wishes he had a little more experience to fall back on.

Finally, consider Linda. As a software development team lead, she spends a lot of time with customers, team members, and contractors. Linda groans as she sees all tomorrow morning blocked out for the annual mandatory compliance training. Just like last year—staff from legal and HR lecture on everything from taking gifts from clients to insider information laws and penalties. And this year there is a new policy—NO mobile devices on during the training! “I really could use the time to review the latest project plan revision! How can I get around this time-waster?”

If any of these situations sound familiar, you may find a solution in scenario-based e-learning.

The complexity of 21st century work is rooted in expertise. And as the word implies, expertise grows out of experience. In fact, psychologists who studied experts in sports, music, and strategy games like chess have found that people require about ten years of sustained and focused practice to reach the highest levels of competency in any domain. However, today’s organizations don’t have ten years to grow expertise. And some skills such as reacting to emergencies demand practice before the situation arises. Are there some ways to accelerate expertise outside of normal job experience? Are there some training techniques to turn a compliance meeting into a more relevant and engaging experience? One answer is scenario-based e-learning.

SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING: A FIRST LOOK

Let’s begin with a couple of examples. I will draw on seven main lesson examples throughout the book and you can see an orientation to these lessons in Appendix A. In addition, you can find color screen shots from these lessons at www.pfeiffer.com/go/scenario. One set of online screen shots is organized in the sequence in which they appear in the book. You can refer to these as you read the book. A second set shows multiple screen shots from several of the main lessons in their logical instructional sequence to illustrate how an intact lesson might flow.

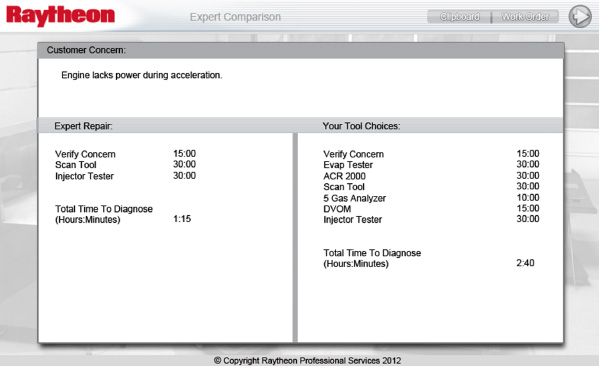

Figure 1.1 illustrates a virtual automotive repair bay. After reviewing a work order, the student technician can access the various on-screen shop tools to run virtual diagnostic tests. The results are saved on his virtual clipboard. As he works through the problem, he can access the company technical reference guides on the online shop computer as well as expert advice through the telephone. When he is ready, he can select the appropriate failure and repair from a list of ten failures. After making a selection, the automobile functions normally or continues to show symptoms associated with the failure. At the end of the lesson, he can review his sequence of testing activities, which have been tracked by the program. He can compare his decisions, shown in Figure 1.2 on the right, with an expert solution shown on the left.

FIGURE 1.2. Learner Actions (on Right) Compared with Expert Actions (on Left).

With permission from Raytheon Professional Services.

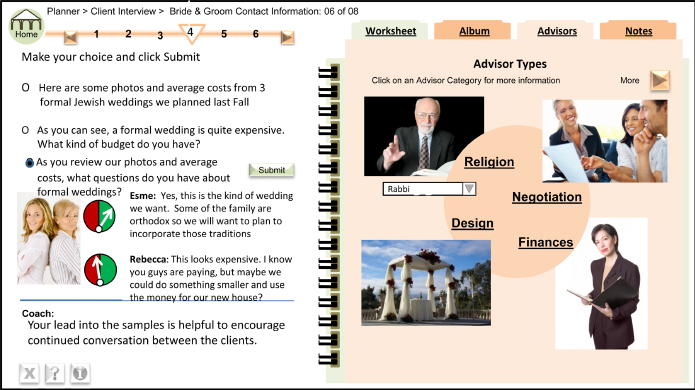

For contrast, let’s take an introductory look at a second example from a demonstration lesson called Bridezilla that Mark Palmer and I designed for newly hired wedding planners. This course uses tabs to navigate to each of four main resources: (1) worksheets where client data is entered and stored, (2) an album that includes examples with financial data for different types of weddings, (3) advisors, and (4) a notes section. In Figure 1.3 I show the menu to access advice on religion, design, negotiation skills, and finances—each a major knowledge and skill domain required for successful wedding planning. Each advisor provides basic information with additional links to various reference sources. Unlike the troubleshooting scenario, the goal of this type of lesson may not be so much to arrive at a single correct answer but to offer a context for learning basic knowledge and skills about wedding planning. Most of the wedding solutions will involve tradeoffs, and the scenarios offer the opportunity to build experience around those tradeoffs.

FIGURE 1.3. The Learner Can Access Virtual Advisors for Wedding Planning.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

We’ll see more of these lessons as well as some different examples throughout the book. Remember that you can see a set of screens organized either by course or in the same sequence that they appear in this book online at www.pfeiffer.com/go/scenario. However, based on just these two examples, check which features below characterize scenario-based e- learning:

You can see my answers at the end of the chapter. Take a look now if you can’t wait—or find most of the answers by reading the next few pages.

SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING DEFINED

I know it’s not too exciting to start a discussion with a definition. However, our training field actually needs more definitions because we routinely use the same words to mean different things and different words to mean the same thing. No point in moving forward until we make a good attempt at a common understanding. Here’s my definition:

Let’s look at this definition in more detail.

The Learner Is an Actor Responding to a Job-Realistic Situation

By actor, I mean that the learner is placed in a realistic work role and takes on-screen actions to complete a work assignment or respond to a work challenge. Because the environment is highly learner-centric, a key feature of scenario-based e-learning is high engagement learning. In traditional instructional environments such as a slide-based presentation, the learner is an observer and listener—primarily playing the role of a passive receiver. I call these learning environments receptive or “show and tell.”

In directive environments, the learner observes and listens and periodically responds to some questions or a short exercise based on what she has heard and seen. In these moderately engaging environments, the learner is a receiver and an occasional responder to highly structured questions. Procedural software training often reflects this type of design. In contrast, in scenario-based e-learning, the learner assumes the role of an active respondent from the beginning and continues in that mode throughout the lesson.

The Environment Is Preplanned

Like any well-designed training, there are defined learning objectives and desired knowledge and skill outcomes which are the focus of the lesson design. For example, in the automotive technician training, the objective requires the learner to follow an efficient and accurate process to perform and interpret diagnostic tests in order to identify the correct failure and repair action. In Bridezilla, there is no single “correct” answer. Instead, the objective is to help learners make decisions during wedding planning consultation that reflect the religious, financial, aesthetic, and social values of the clients. As the learner works with different virtual clients, she has the opportunity to learn about diverse cultural, religious, aesthetic, and financial aspects of weddings as well as to apply problem-solving skills in negotiating discrepancies in client resources or opinions.

Learning Is Inductive Rather Than Instructive

In inductive environments, the emphasis is on learning from a series of progressively complex experiences by taking actions, reviewing responses to those actions, and reflecting on the consequences. For example, the automotive technician student has the opportunity to try a diverse sequence of tests (some more relevant than others) and to learn from the results of his choices. Contrast this approach with a directive design that emphasizes learning from a structured series of explanations and short practice exercises. For example, a traditional course design teaches the five stages of a troubleshooting process along with associated tools by presenting steps, giving examples, and assigning structured practice activities.

The Instruction Is Guided

One of the most important success factors in scenario-based e-learning is sufficient guidance to minimize the flounder factor. A recent meta-analysis summarizing more than five hundred studies that compared a discovery approach with either directive or guided discovery, found significantly better learning among the more guided versions (Alfieri, Brooks, Aldrich, & Tenebaum, 2011). There are a number of ways you can provide guidance, ranging from case complexity progression (low to high), amount of support provided (high to low), and interface and navigation design. Chapter 6 is devoted solely to techniques and examples for guidance in scenario-based e-learning environments.

Scenarios Incorporate Instructional Resources

Unlike most games that rely solely on inductive learning, scenario-based e-learning environments embed a number of resources for explicit learning, including virtual coaches, model answers, and even traditional tutorials. As illustrated in Figure 1.3, the scenario offers a number of virtual coaches as sources for diverse perspectives on wedding planning. Like a game, scenario-based e-learning presents a challenge. However, competition to achieve a particular score or out-play others is not an essential feature and can even be counterproductive. In Chapter 7 I will illustrate different approaches you can use to embed instructional opportunities in your learning environments.

The Goal Is to Accelerate Workplace Expertise

By working through a series of job scenarios that could take months or years to complete in the work environment, experience is compressed. At its core, scenario-based e-learning is job experience in a box—designed to be unpackaged and stored in the learner’s brain. Unlike real-world experience, scenario-based e-learning scenarios not only compress time but also offer a sequence and structure of events designed to guide learning in a controlled manner. The automotive technician and the wedding consultant would most likely eventually learn the skills needed on the job. However, rather than months and years, the multimedia compressed experiential environment shrinks the learning experience into a matter of hours.

You will discover a wide range of design options that reflect these six features that I designate as key elements of scenario-based e-learning. One of my goals is to help you adapt these features to meet the specific goals, learners, and resources available in your organization.

What’s in a Name?

Before we leave this section on definitions, as I mentioned previously, in our profession, we have few consistent terms. What I am calling scenario-based e-learning has also been labeled problem-based learning, whole-task learning, guided discovery, immersive and goal-based learning, to name just a few. Almost every time I do a workshop, I hear a new term. I know that some experts have precise definitions for these various instructional designs. And if your organization has a different term, feel free to stick with it. For consistency I’m going to use scenario-based e-learning. However, my goal in this book is to provide some guidelines and examples to help you to design learning environments that are task-centered, engaging, and designed to accelerate expertise, regardless of what you want to call them.

SCENARIO-BASED VS. DIRECTIVE TRAINING ENVIRONMENTS

Let’s contrast a scenario-based e-learning design to a more traditional approach, known as a directive or part-task design. In Table 1.1 and the discussion to follow I summarize some of the main differences.

TABLE 1.1. Scenario-Based e-Learning vs. Directive Training Environments

| Feature | Scenario-Based | Directive |

| Role of Case Study | Lesson begins with the case The case serves as a context for learning |

Lesson ends with the case The case serves as culminating application for learning |

| Lesson Organization | Holistic—Variable chunks Knowledge and skill components integrated into the case assignment | Hierarchical—Small Chunks Knowledge and skill components build from simple to more complex culminating in case assignment |

| Role of Learner | An actor to resolve challenges and tasks in the scenario | A responder to frequent and structured questions designed to build knowledge and skills |

| Role of Instruction | Provide a realistic engaging scenario accompanied by resources to support learning | Provide highly structured content, examples, and practice with feedback to support learning |

| Instructional Approach | Inductive—Learning from experience and reflection on the consequences of actions taken or decisions made | Instructive—Learning from a structured, organized sequence of exposition, examples, and frequent content-specific practice exercises |

| Interactivity | High overt learner activity in an environment of moderate to high levels of learner control over actions | Moderate overt learner activity during periodic structured interactions |

| Feedback | Consequential in which the learner takes actions, makes decisions and experiences the outcomes as well as corrective in which the learner is told whether the response is accurate and why | Corrective, in which the learner responds to structured questions and is told (usually immediately) whether a response is accurate or not and why |

| Best Uses | Building critical thinking skills and experience in strategic tasks Accelerating expertise when on-the-job training is unsafe, impractical, or too slow Motivating learners through job-relevant scenarios |

Building procedural skills to learn relatively routine tasks Offering efficient paths to learning knowledge and skills associated with procedural tasks |

| Target Audience | Often best suited for apprentice workers who already have relevant work background experience | Often best suited for learners who are new to the knowledge and skills included in the training |

If you have designed, taught, or taken a beginning software course, you are familiar with a directive design. Traditional procedural training, also known as part-task or directive, typically follows a “rule-example-practice-feedback” sequence. Directive training based on behaviorist learning psychology emphasizes learning based on stimulus (question)-response (response to the question) and feedback (immediate knowledge of results). Typically, the job role is parsed into a number of small tasks, each to be taught in a lesson that states and demonstrates steps, assigns practice, and gives immediate corrective feedback.

Take an Excel class, for example. The goal of using a spreadsheet is broken into a number of small tasks, each with associated key knowledge topics. For example, topics such as What is a cell? What are cell references? or What are formulas? are explained and demonstrated by the instructor using a simple spreadsheet. Next the students practice constructing and inputting several formulas following step-by-step directions. When they make a mistake, they receive immediate feedback and correct their responses. After completing several lessons, a small business case study gives students the opportunity to consolidate and practice the component skills in a holistic context.

In contrast, in scenario-based e-learning, the lesson kicks off with a case assignment. For example, in an Excel lesson, the learner is given a simple spreadsheet for a small business and asked to calculate weekly sales totals. Rather than receiving a series of structured lessons and demonstrations, the learners are free to try different actions and also to access reference and guidance resources as they proceed. Learning and reference resources are embedded or linked into the scenario environment.

Learning from Mistakes

Compared to directive designs, scenario-based e-learning assumes quite a different attitude toward mistakes. Rather than viewing errors as negatives to be hopefully avoided or at least immediately corrected, in scenario-based e-learning mistakes are seen as learning opportunities. As Neils Bohr said: “An expert is someone who has made all of the mistakes that can be made in a limited domain.” In some scenario-based e-learning designs, as in the real world, learners may not realize they’ve made some poor decisions until they are near the end of the case. In the automotive example, only after the learner selects the correct failure and repair activity, does he see the consequences of his choices by comparing his process with that of an expert. In other scenario-based e-learning lessons, feedback is provided with each step. In Chapter 8, you can review much more detail about the what, when, and where of feedback in scenario-based e-learning.

Scenarios to Lead or to Culminate?

Purists will argue that true scenario-based learning leads with the scenario, which serves as the engine for learning. Various learning resources are linked into stages of scenario resolution. However, I’ve seen several clients switch from using the scenario as a lead-off event to preceding it with a structured series of lessons. I’m not sure of all the reasons, but I suspect that, in some situations, the mental load imposed by learning while resolving a problem was too heavy for many learners. Instead, they have found it more effective to use the scenario as a culminating learning experience. The best solution no doubt depends on the prior knowledge of your learners and the complexity of your instructional goals.

In Chapter 10, which summarizes research evidence related to scenario-based e-learning, I will describe some experiments showing benefits of starting with a scenario followed by directive training and others showing benefits of preceding a scenario-based simulation with directive training. Whether your scenario initiates or follows directive instruction, the guidelines in this book are applicable to your scenario design.

Target Audience

Because learning new knowledge and skills while solving a job-realistic problem can impose quite a bit of mental load, in general scenario-based e-learning is best suited to learners who already have some job experience. For example, the automotive trouble shooting lesson would likely be quite overwhelming for learners unfamiliar with common testing equipment in a service bay. In contrast, a directive approach is well suited for workers with new job roles or assignments. Because the directive approach offers small chunks in a hierarchical sequence, the learner is spared excessive mental overload.

WHAT SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING IS NOT

It might be helpful to clarify what scenario-based e-learning is by looking at a few examples that could be misclassified as scenario-based e-learning. Here are some of my favorites:

Not a Game

Clark and Mayer (2011) define games as a competitive activity with a challenge to achieve a goal, a set of rules and constraints, and a specific context. How is scenario-based e-learning different? Like a game, scenario-based e-learning does pose a challenge, and there may also be rules and constraints. However, an element of competition is not the essential feature that it is in games. Second, an essential feature of scenario-based e-learning is a specific context—the context of the workplace. Some games may embed a work context, but many do not.

Although scenario-based e-learning could have a game overlay—say by tracking and showing progress “scores,” there is no solid evidence that a competitive element will lead to better learning. In fact, if you want to wrap your scenario-based e-learning in a game shell, you need to be careful that the activities and rewards associated with game progress are aligned to your learning goals. In summary, while some scenario-based e-learning could be designed with gaming elements, I view scenario-based e-learning and serious games as two separate approaches to learning.

Not a Scenario with Questions

I have seen lessons called scenario-based e-learning that consisted of a work scenario followed by a series of multiple-choice or open-ended questions about the scenario. For example, learners view a customer service interaction. Then they respond to questions such as: How could the customer service representative have responded more effectively? Which of the following principles did the customer service representative apply when she . . .?

While these kinds of scenario-driven exercises have learning value, they fail to incorporate all of the features of a scenario-based e-learning environment. In particular, the learner does not become an actor in the scenario. Rather, he or she is more of an observer reflecting on and analyzing it. Often these types of lessons approximate a directive design more than scenario-based e-learning.

Not a Simulation

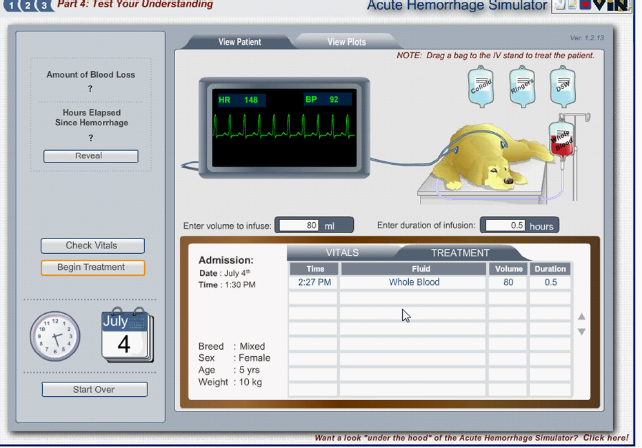

Although scenario-based e-learning can be based on a simulation, simulation is not an essential element. I define a simulation as a dynamic model of a real-world phenomena or process often simplified to reflect core principles. Neither the automotive troubleshooting nor the Bridezilla examples I introduced in this chapter are based on a truly dynamic simulation. In contrast, in Figure 1.4 I show a scenario-based e-learning lesson on emergency treatment for blood loss in dogs. In this simulation, the learner has a choice of different treatments for a dog with blood loss. As treatment decisions are made, the student can review dynamic changes in the dog’s status reflected in the on-screen EKG. The EKG responses are programmed with a mathematical model based on known physiological responses.

FIGURE 1.4. A Scenario-Based e-Learning Simulation of Treatment of a Dog for Blood Loss.

With permission from the Veterinary Information Network.

Not About a Delivery Mode or Media

You could present your scenario entirely in text—although evidence is accumulating that, at least for tasks that rely on discrimination and interpretation of sights and sounds, some visualization of the case promotes learning. A scenario-based e-learning lesson could be “delivered” as a stand-alone self-study digital resource either on the Internet or on a CD. Alternatively, it could serve as a resource in an instructor-led training (ILT) environment—in either a face-to-face or virtual classroom. In an instructor-led environment, learners could review the case as prework or as an initial learning exercise at the first meeting. Then, depending on the outcome goals, the instructor can provide learning resources, assign teams to select and discuss scenario actions and resolutions, and offer teams opportunities to present and debrief their solutions. A recent meta-analysis reports that blended learning environments that incorporate both synchronous and asynchronous events result in better learning than either instructor-led or self-study alone (U.S. Department of Education, 2010).

Not About Specific Technology

Scenario-based e-learning is an instructional design approach that can be realized with a range of technologies as simple as a branching PowerPoint or as powerful as the automotive troubleshooting scenario created with HTML/Flash. The point is: Don’t think you need high-end or new technologies to implement it.

SIX REASONS TO CONSIDER SCENARIO-BASED E-LEARNING NOW

Why should you consider how you can adopt scenario-based e-learning to meet your organizational learning needs now? After all, some forms of scenario-based learning have been around for forty years. Problem-based learning (PBL) was initiated in medical education at McMasters University in the 1970s. In a PBL curriculum, rather than taking a series of science classes, such as anatomy, pathology, or bacteriology, medical students meet in small groups to review, discuss, research, and resolve a patient case. Over the past forty years PBL has gone global and expanded beyond medical education into a variety of other professional domains.

Here’s my list of reasons you might want to consider investing time and resources in scenario-based e-learning now:

1. Scenario-Based e-Learning Can Accelerate Expertise

There is no substitute for experience as the basis for job competence, and scenario-based e-learning offers opportunities to gain experience in a safe and controlled manner. The world of work often includes tasks that occur infrequently. For example, some automotive failures are relatively rare. Scenario-based e-learning can focus specifically on those scarce opportunities.

Second, the world of work does not usually present learning opportunities in the best sequence for learning. But in scenario-based e-learning a series of simulated work challenges can be organized from simple to complex, thus assuring a smoother learning curve.

Third, responding to high-risk tasks such as emergencies cannot be readily practiced in a real-world environment. Scenario-based e-learning can build cases from records of actual incidents to help learners gain expertise before it’s needed.

2. Scenario-Based e-Learning Can Offer Return on Investment

Most likely before you begin a major training initiative, you need to present a business case. In situations in which on-the-job experience is rare, dangerous, or impractical, scenario-based e-learning can provide a cost-effective option. For example, the automotive troubleshooting lessons could be learned on the job or in a teaching shop using cars with various failures. However, a cost-comparison of these three alternatives found that a scenario-based e-learning approach offered the best return on investment. See Chapter 12 for more details on making a business case for scenario-based e-learning.

3. Learners Like Scenario-Based e-Learning

Evaluation of PBL in medical education finds that most medical students like it better than the traditional science-based curriculum. Why? I think the answer is relevance. Because medical students have patient-care career goals, they find learning in the context of a patient case more motivating than learning science facts in a decontextualized manner. A second satisfier is engagement. In scenario-based environments, the learner is the main actor and spends most of his or her time interacting in the scenario world.

Remember Linda, who was dreading taking the annual compliance training consisting of a series of lectures on company policies? Imagine her reaction to being told that she can take the required course any time in the next quarter on the intranet in approximately two hours. Further, once logged in, she finds herself in the position of having to immediately make a decision about accepting an offer of some game tickets from a client. Before she knows it, she’s not only physically but also mentally engaged in the experience and starting to consider how corporate policies apply to her work.

4. Scenario-Based e-Learning Has Better Transfer Potential

How often have you taken a class but never really used the skills back on the job? The class may have contained some useful knowledge, but it was not presented in a way that could be readily applied to your work setting. Scenario-based e-learning provides a solution to transfer failure. Because scenario-based e-learning is all about context, you learn in an environment that mirrors the job or something similar to it. Rather than attending lectures on compliance policies and laws, you apply those policies by resolving compliance dilemmas. Your new knowledge is contextualized and indexed in your brain in a manner more likely to be retrieved when needed on the job.

5. Scenario-Based e-Learning Can Build Critical Thinking Skills

While directive designs are effective for learning procedures, they are often limited when it comes to building knowledge and skills for more strategic tasks that do not have a simple correct or incorrect answer. In the next chapter we will look in greater detail into the types of tasks, outcome skills, and learners who benefit most from scenario-based e-learning.

6. Technology Can Facilitate Scenario-Based e-Learning Development

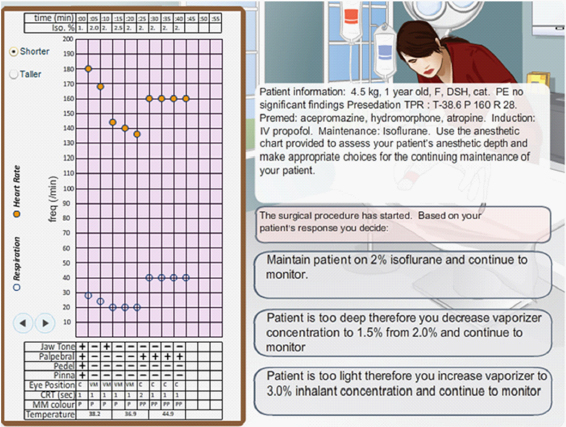

Recent advances in authoring resources make it much easier to construct a scenario-based e-learning lesson than has been the case in the past. In fact, some authoring programs are designed specifically for that purpose. But you don’t need a huge arsenal of authoring expertise either. For example, some lessons, such as the anesthesiology lesson shown in Figure 1.5, could be developed using basic presentation software with feedback links from the on-screen options selected.

FIGURE 1.5. A Branched Scenario Can Be Based on Links in Presentation Software.

With permission from Veterinary Information Network.

WHAT DO YOU THINK? REVISITED

In the beginning of the chapter, you had the opportunity to select which features below characterize scenario-based e-learning:

My answers are Items 1 and 4. Regarding Options 2 and 3, while simulations and high-end media may characterize some scenario-based e-learning, they are not essential. The blood loss emergency treatment lesson is based on a simulation. In contrast, the Bridezilla and anesthesiology examples use branching logic and rely on text with static graphics to support the scenario. Options 5 and 6 apply more to directive designs than to scenario-based e-learning.

COMING NEXT

I ended this chapter with six reasons to consider scenario-based e-learning now. But there are multiple issues to consider. With every new instructional approach and technology, there are those enthusiasts who believe the new should totally replace the old. I don’t agree. Instead, I believe that there is a time and place for older as well as for newer designs. Furthermore, learning can be blends of different design approaches. In the next chapter I focus on the when and for whom of scenario-based e-learning. My goal in that chapter is to help you further pinpoint opportunities for scenario-based e-learning in your organization.

At the end of each chapter, I will present a short worksheet or questions to help you apply the guidelines to your own instructional goals. Naturally, you can review these—or bypass them for now. All of the worksheets and checklists can be found online at www.pfeiffer.com/go/scenario. Password: Professional.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Task-centered design models—what I’m calling scenario-based e-learning—have been described in several recent books. Two I have used as resources are

Merrill, M.D. (2012). First principles of instruction. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

A very comprehensive text that describes common design principles for all effective instructional environments with an emphasis on scenario-based learning designs.

Van Merrienboer, J.J.G., & Kirschner, P.A. (2007). Ten steps to complex learning. New York: Routledge.

Based on their research, the authors of this book describe a model for designing task-centered instruction including scenario-based e-learning.