CHAPTER 2

WHEN TO USE SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING

When it comes to designing learning environments, there is no yellow brick road. By that I mean there is no single path that is best for all purposes and all learners. Perhaps after reviewing the six reasons that scenario-based e-learning might work for you now listed in Chapter 1, you are starting to think about how you have used or might apply this approach to your own training needs. In this chapter I will describe the types of tasks, learning outcomes, and learners who are good candidates for scenario-based e-learning designs. I also introduce four navigation/interface designs for scenario-based e-learning. Specifically, as you read this chapter, you will see how scenario-based e-learning applies to:

- Strategic versus procedural learning goals

- Features specific to tasks and learners

- Eight knowledge and skill objectives

- Eight learning domains

- Four navigation and interface designs

CONSIDER SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING FOR STRATEGIC TASKS

I divide learning goals that require skill building into two main categories: procedural tasks and strategic tasks. Procedural tasks are routine work activities that pretty much follow the same sequence each time they are performed. Logging into e-mail and completing an online timesheet are two common examples. Procedures can be broken down into steps and are trained most efficiently by the directive approach I described in Chapter 1.

Scenario-based e-learning is generally better suited to strategic tasks that require judgment and tailoring to each new workplace situation. Unlike procedures, strategic tasks cannot be decomposed into a series of invariant steps. Instead, strategic tasks require a deeper understanding of the concepts and rationale underlying performance in order to adapt task guidelines to diverse situations. Some common examples of strategic tasks include making a sale, designing a website, or evaluating a loan application. The experienced sales person adjusts her approach with each engagement, depending on the client, the product, and the sales context.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

Put a checkmark next to each task below that you think is a strategic task:

Your answers will depend on your experience with and assumptions about those tasks. Here are my thoughts. Task 1 is most likely a procedural task and would be best trained by a demonstration, practice and a job aid following a directive training plan. In fact, if the order form is simple enough, a performance aid alone may suffice. Tasks 2 through 4, however, I categorize as strategic tasks because they require judgment and/or problem solving, and there is rarely a single right answer. For example, there may be a flow chart for troubleshooting many routine failures. Something unusual, however—say two simultaneous failures—might not be captured on a flow chart. It would be just about impossible as well as cost-ineffective to document all possible combinations of failures. Instead, an individual with a deeper understanding of the equipment and a rich bed of experience would draw on her mental index of failures and rules of thumb to isolate and resolve the problem.

How about meatloaf? What kind of cook are you? Do you pull out your cookbooks and follow a recipe? If yes, you are a procedural cook. Or do you construct your own creations using your past experience and a pinch of instinct? Fast-food organizations definitely apply a procedural approach. Their goal is a consistent product produced by a high turnover of relatively low skilled workers. In contrast, the culinary school I visited in Hawaii focuses on the principles and economics of cooking—not just the procedures. In one culinary class, for example, learners might make five cakes, leaving out a key ingredient each time. In that way the budding chefs experience directly the effects of the salt, flour, sugar, and baking powder on the final product.

The point of the meatloaf digression? Some tasks such as cooking can sometimes be treated as procedures and other times as strategic tasks. Whether a task is treated as procedural or as strategic may depend on the business model and constraints of the organization. For fast-food preparation, the emphasis may be procedural; for a culinary professional, a deeper level of understanding is needed. Therefore, you will need to consider the context of your organization as you define the best approach.

SITUATIONS THAT CALL FOR SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING

In addition to focusing on a strategic task, there are a number of other contextual factors that could point you toward a scenario-based e-learning design. These relate to the frequency, criticality, timeline, and goals for the task, as well as to the prior experience level of the learners. Here I summarize some of the more common indicators:

Rare Occurrence Tasks

Some situations that require problem solving simply don’t pop up that often on the job. In Chapter 1 I mentioned research showing that most experts require a solid ten years of sustained practice to reach highest proficiency levels. One reason is that the real world rarely serves up scenarios in an ideal learning sequence. Take troubleshooting. You are likely to see plenty of certain kinds of failures. However, other failures may be much more infrequent. If you identify those infrequent tasks, you can package them in scenario format and offer virtual opportunities to build expertise in their resolution. Another example is supervisory challenges. For example, a new supervisor may not have to hire a new employee or initiate disciplinary action for months. By embedding hiring or discipline scenarios in a scenario-based e-learning course for new supervisors, they can gain initial experience not otherwise feasible.

Critical Thinking Skills Training

Most strategic tasks will require critical thinking skills to enable workers to adapt their experience to new situations. Research on the reasoning skills of experts shows that critical thinking skills are domain-specific. By that I mean that the facts, concepts, rules of thumb, and rationale that a military commander would consider when responding to a situation are quite different than those of a physician. Training on very general thinking skills such as “brainstorm alternatives” or “break the problem into smaller parts” will have limited transfer to real work decisions. Instead, for successful learning, you need to identify and teach critical thinking skills that are unique to the work domain.

You may be familiar with Bloom’s Taxonomy. Initially published in 1956, recent revisions have updated the original (Anderson et al., 2001). Other psychologists have put forth slightly different classifications of knowledge and skills involved in critical thinking (Leighton, 2011). As of now there is no single agreed-on classification system. Drawing on the commonalities among several of these taxonomies, in Table 2.1 I summarize eight knowledge and skill categories associated with many problem-solving tasks in the workplace.

TABLE 2.1. Common Knowledge and Skills Required in Workplace Tasks Involving Critical Thinking

| Knowledge/Skill | Learner Is Able to | Examples |

| 1. Remember or Access Facts | Recall or look up relevant discrete information | Describe product features and benefits Name object (equipment, anatomy) parts Identify relevant policy |

| 2. Apply Concepts | Classify data, objects, events, or symbols into categories | Select the circuit with the correct resistance Distinguish abnormal breathing patterns |

| 3. Perform Procedures | Complete a task that is performed the same way each time | Close a valve Log into the system Enter data into the correct fields |

| 4. Apply Mental Models | Demonstrate an understanding of how systems behave | Draw a model of heart circulation Select what would happen next in the equipment start-up phase |

| 5. Analyze Situations | Define the problem, identify and prioritize relevant data, interpret data | Verify an equipment failure Identify and conduct appropriate tests Assess the validity of data Interpret graphs and charts |

| 6. Apply Rules of Thumb | Make decisions or take actions based on domain-specific problem-solving guidelines | Use split-half testing approach Ask open-ended questions |

| 7. Create a Product | Build, write, or produce a deliverable that optimizes situation constraints and goals | Write a report Create a marketing plan Build a prototype Respond in a role play |

| 8. Monitor Progress | Assess the current status of a situation against constraints and desired outcomes and take actions to readjust as needed | When system does not respond as anticipated, evaluate and change parameters If the prototype does not meet specifications, readjust relevant features |

Most problems of any degree of complexity will involve several of these knowledge and skills. However, in different problem domains, some may be more critical than others. For example, troubleshooting will draw heavily on the following knowledge and skills: facts and mental models of the target equipment; the analysis of failures, including gathering and interpreting data; the application of rules of thumb specific to the domain; and the ability to monitor progress and adjust as needed. As you frame your desired learning outcomes and supporting knowledge, you can adapt many of these knowledge and skill categories to the target domain of your training.

Compliance-Mandated Training

I mentioned compliance training in Chapter 1. Most large organizations have regular training required of many workers for compliance with legal mandates or corporate policy. Typical topics involve information security, safety, ethical conduct, or HR issues such as sexual harassment. Frequently, these classes consist of policy lectures with a few war stories thrown in. As an alternative, consider scenario-based e-learning to immerse learners in a situation requiring them to make a decision in a context related to application of policies and then experience the consequences of their decision.

Learner Expertise and Scenario-Based e-Learning

In many cases scenario-based e-learning designs are best matched to more experienced workers already familiar with the basics of the environment—the equipment, the terminology, the context. For a novice worker, a scenario-based e-learning lesson may be overwhelming, with visual interfaces that offer too many choices and not enough structure. Therefore you might target scenario-based e-learning for apprentice level workers or for post-introductory levels of training.

Lengthy Timeline Tasks

In some situations, actions and decisions in the workplace can unfold over a period of weeks or even months. Even a relatively simple troubleshooting dilemma could require tests that take hours, ordering new parts that requires days, and so on. In a scenario-based e-learning environment you can compress time. Want to execute a troubleshooting test? Click on the test equipment and the test is “run.” Want to replace a part? Click on a part on the screen and it is replaced. The consequences of these decisions and actions can be seen immediately. The result is a much closer alignment of actions to consequences and the opportunity to resolve many situations in a short period of time.

Risk-Adverse Tasks

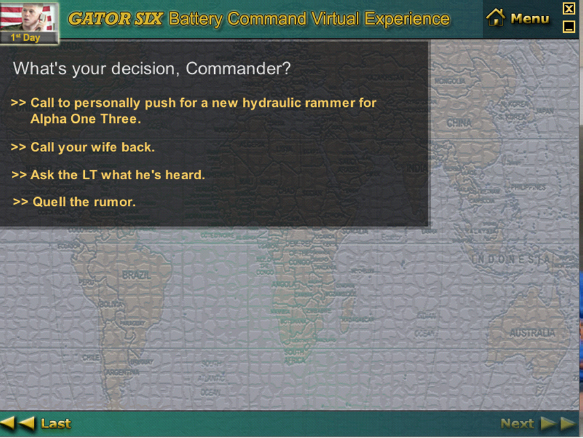

Some tasks simply cannot be learned through normal work experience. The consequences of errors are too high. Tasks with injury consequences are one example. The new military commander faces his first combat assignment as team lead. Inappropriate responses to multiple unknown and unanticipated problems can result in lethal consequences. For example, a scenario-based e-learning course for military officers called Gator 6 starts off with a failed military operation in which soldiers and civilians die unnecessarily. Figure 2.1 shows a screen shot from the introduction to this program. The learner assumes the role of the commander and goes back in time with the opportunity to make decisions that will result in a better outcome. The anesthetics lesson illustrated in Figure 1.5 is another example of a high-risk task.

FIGURE 2.1. Unnecessary Causalities Result from Poor Leadership Decisions.

With permission from Will Interactive.

Failing to interact effectively with an important person is yet another example. In the real world you may not get a second chance to make a good impression. For example, a soldier meets a village elder. What should he say? How should he act? How should he interpret the responses of the elder in a specific cultural setting? While scenario-based e-learning may never replace the real thing, even some basic exposure to a new environment can translate into a performance booster.

EIGHT SCENARIO-BASED LEARNING DOMAINS

So far I’ve reviewed some general situations that lend themselves to use of scenario-based e-learning. Now let’s zoom into some specific workplace domains that will benefit. In Table 2.2 I summarize eight domains that reflect the most common applications of scenario-based e-learning. These domains are not mutually exclusive and do not reflect all potential applications of scenario-based e-learning. But they do provide a starting place for planning. Here I describe each in a bit more detail:

TABLE 2.2. Eight Scenario Learning Domains in Workforce Training

| Domain | Desired Outcome | Examples |

| 1. Interpersonal Skills | Communicate effectively to achieve operational goals | Customer service Sales |

| 2. Compliance: Policies and Procedures | Select actions or responses that best comply with legal and organizational policy guidelines | Supervisor tasks Information security Safety |

| 3. Diagnosis and Repair | Access and interpret relevant data, diagnose problem, perform repair or prescribe treatment | Equipment troubleshooting Allied health professionals |

| 4. Research, Analysis, and Rationale | Identify and assess data sources; make optimal decisions or recommendations based on rationale | Bank loan analysis Journalism |

| 5. Tradeoffs | Apply knowledge to take actions or make decisions for which there may be multiple solution paths or solutions | Project planning Making ethical decisions |

| 6. Operational Decisions and Actions | Take actions in simulated production or operational environments to optimize performance | Production control adjustment Aircraft navigation |

| 7. Design | Create an original product to meet scenario constraints—no single correct solution | Design a website Conduct a needs assessment Develop a project plan |

| 8. Team Coordination | Communicate and coordinate activities among specialists to achieve an objective | Deploy resources to respond to a disaster situation such as a hurricane |

1. Interpersonal Skills

In this category I include communication tasks such as those involved in customer service, sales, management, or teaching. Interpersonal scenarios typically follow a linear sequence of “he says . . . she responds.” You can design highly structured scenario environments with limited choices for entry-level lessons and evolve to open role-play environments for more advanced lessons. For example, in Figure 1.3 you can view a segment from a client interview led by the wedding consultant. Regarding knowledge and skills, interpersonal domains will often require remembering or accessing factual information such as product knowledge, applying concepts such as open-ended questions or empathy, analyzing situations such as a client’s requirements, applying rules of thumb such as start with open-ended questions, and monitoring progress, including making adjustments based on body language of the respondent.

2. Compliance Policies and Procedures

Here I incorporate actions and decisions made by leaders such as supervisors, managers, and military officers as well as staff actions or decisions that reflect application of policies. Management work certainly involves interpersonal skills but also requires knowledge of organizational policy or legal issues. In this scenario-based e-learning domain, the major emphasis is on appropriate application of these policies. Relevant knowledge and skills include remembering or accessing factual information such as policy references, applying concepts such as recognizing a compliance violation, analyzing situations that involve compliance issues, and applying rules of thumb such as taking organizationally approved action when confronting a policy violation.

3. Diagnosis and Repair

Work in this domain typically involves verifying, researching, and resolving failures. The typical scenario is initiated by a failure, be it a sick cat for a veterinarian or an automotive failure for a technician. Most flavors of system troubleshooting fall into this category as well as medical diagnostics and treatment decisions. One important element of these scenario-based e-lessons is an emphasis not only on individual actions or decisions but on the entire sequence of decisions made. For example, in automotive troubleshooting, the technician could take an inefficient random approach to tests. Eventually she may resolve the problem but waste a great deal of time in the process. Therefore the scenario-based e-learning design should allow learners multiple solution paths and provide instruction and feedback on those paths. In other words, the focus is not only on a correct answer but also on the process for deriving the answer.

Related knowledge and skills include remembering or accessing factual information such as a schematic diagram for equipment, applying concepts such as a functional circuit, performing procedures such as using test equipment, applying mental models such as understanding how the equipment works, analyzing failures, applying rules of thumb for testing, interpreting test data, and analyzing repair alternatives as well as monitoring progress. Although this domain incorporates multiple knowledge and skills, often the problems are relatively structured. By that I mean, there is typically a correct answer that leads to appropriate functioning of the system.

4. Research, Analysis, and Rationale

Many workplace contexts require the worker to achieve a goal by identifying and gathering relevant data, evaluating that data, and making decisions or taking actions based on a rational synthesis of information available. The diagnostics worker discussed in the previous paragraph is also engaged in research and analysis. However, the difference here is that the trigger event need not be a failure or problem. For example, when evaluating a new loan candidate, the underwriter must access and evaluate a number of data resources about the applicant. Similar to the diagnostic cases mentioned previously, there is usually an efficient sequence to follow. Likewise, when a decision is made, often a rationale for that decision is an important element.

Related knowledge and skills can include any of the eight listed in Table 2.1, but typically rely heavily on applying concepts, analyzing situations, and creating a product such as a loan justification form.

5. Tradeoffs

At times there really is no single “best” answer or resolution to a work dilemma. Your instructional goal in a tradeoff scenario-based e-learning design is not to derive a correct answer. Rather, the focus is an engaging context for learners to review multiple perspectives or applicable policies or laws as they make a decision or take an action. The feedback may show consequences of decisions made; however, all decisions will have positive and negative consequences. For example, in the Bridezilla lesson, learners have an opportunity to seek input from diverse sources of expertise, including clergy, designers, finance, and negotiations experts. In a project planning lesson, decisions will need to weigh the tradeoffs among budget, schedule, resources, and politics, to name a few.

Tradeoff lessons at an introductory level may focus on remembering or accessing factual information such as average costs for formal wedding receptions, applying concepts such as formal versus informal weddings, analyzing situations, and creating a product such as a project plan and budget. Monitoring progress will be another important element for the wedding planner since the project will play out over an extended period of time and involve coordination of multiple elements.

6. Operational Decisions and Actions

The goal of these scenarios is to offer opportunities for operators or technicians to make decisions and take actions in the context of a (usually simulated) operational environment. Training for power plant operators or medical procedures such as laparoscopy are two examples. Typically, large-scale operational environments with major safety consequences use realistic 3D simulators. However, such simulators are expensive and may be supplemented with a lower-fidelity multimedia version. In addition, some operational decisions must be made quickly and thus rely on a degree of automatic performance by decision-makers. Automaticity can be built by using scenarios as a context for drill and practice.

Operational decisions and actions will depend heavily on remembering or accessing factual information, applying concepts, performing procedures, applying mental models, analyzing situations, applying rules of thumb, and monitoring progress.

7. Design

Most of the domains I’ve reviewed so far are relatively structured. That is, they assume there are some defined outcome decisions or action paths. Design scenarios, however, focus on creation of a product that could have multiple effective solutions. Some common examples include developing a website to meet a client’s constraints or designing a marketing plan for a new product. Design goals will require a much more open-ended environment as well as a checklist of desired end-product features to evaluate outcomes. Because design decisions of any complexity typically reflect multiple subtle factors, often human feedback (from an instructor, peers, or expert) will be needed. For this reason, design lessons will be best mediated in an environment of high social presence such as an instructor-led virtual or in-person class.

Among all of the knowledge and skills, design will rest heavily on analyzing a situation, creating a product, and monitoring progress.

8. Team Coordination

In some work settings, success depends on rapid and accurate communication and coordination among multiple specialist workers. Some examples include emergency room medical staff, a combat team, or aircraft crews. Studies of aircraft crews have derived best practices in cockpit resource management that are being adopted by other skilled teams such as medical specialists in operating or emergency rooms.

Some key knowledge and skills especially relevant to team coordination include situation analysis, applying rules of thumb, and monitoring progress.

SCENARIO-BASED MULTIMEDIA INTERFACES

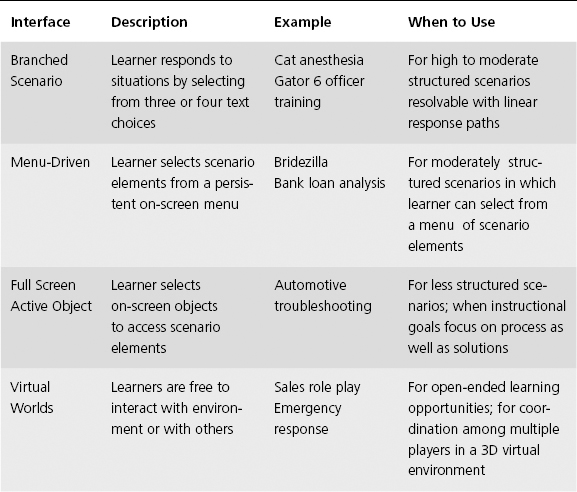

So far I’ve mentioned a number of workplace factors that point toward using a scenario-based e-learning design. In Table 2.3 I introduce four interface-navigation designs commonly used to present scenarios and to support navigation. These interfaces can be mixed and matched to best fit your scenario domain, learner profile, and available technological resources.

TABLE 2.3. Scenario-Based e-Learning Interface-Navigation Options

The four options vary primarily on the type of structure and navigation options offered. Lower levels of learner control that restrict learner choices are most effective for more novice staff and for tasks with relatively defined outcomes. In contrast, more flexible designs are better for more advanced lessons and for tasks with multiple paths or outcomes.

Branched Scenarios

In a branched scenario, the learner is exposed to a brief episode and is offered three or four alternative responses, usually via a text link. For example, the cat anesthetic scenario shown in Figure 1.5 illustrates a typical branched scenario. Patient information is provided in text in the upper right corner and in the left-hand chart. After responding, corrective instructional feedback is given and the learner has the opportunity to select a different option or is presented with a new set of options.

Likewise, the Gator 6 military officer training is based on a branched scenario design. Following the opening video shown in Figure 2.1, the learner goes back in time and has the opportunity to make multiple decisions to improve the final outcomes. For example in Figure 2.2, the learner has time only to respond to one among several demands. As you can see by comparing the anesthesia and military examples, the media can vary from relatively simple still images to video. Branched scenarios lend themselves to tasks with linear progressions such as interpersonal skills and tasks that would unfold over time. Situations in which learners need opportunities to make multiple decisions at a single point in time in order to learn the most appropriate action sequence would not lend themselves as well to a branched scenario approach. Branched scenarios are useful for entry-level lessons because of the degree of structure imposed. Unlike the designs to follow, the learner faces only three or four choices with each transaction.

Menu-Driven

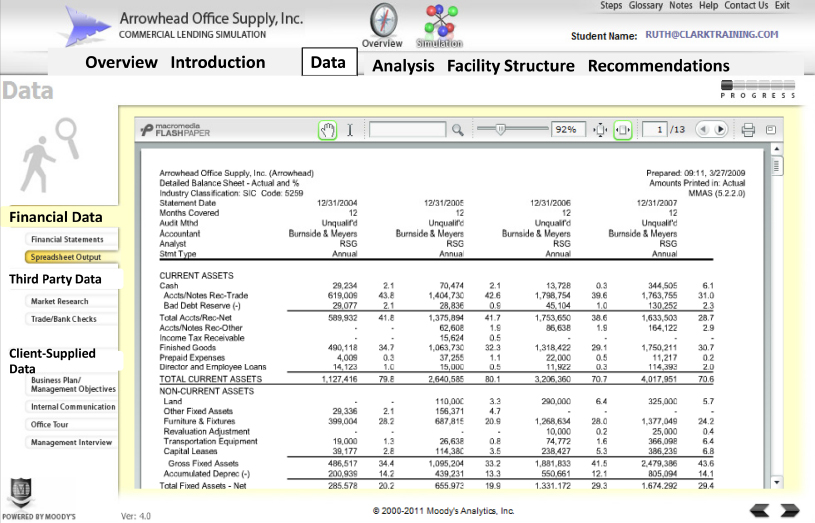

In Figure 1.3 I showed an example of a menu-driven scenario-based e-learning lesson for newly hired wedding counselors. Here the learner has a defined set of options displayed as tabs in the upper right portion of the screen that she can select in any order. A second helpful example, shown in Figure 2.3, is a menu-based design for an underwriter loan analysis scenario. Across the top of the screen are six high-level menu options, including overview, introduction, data, analysis, facility structure/price, and recommendations. These menu options represent the main stages in the analysis workflow. When one of these high-level tabs is selected, the submenus on the left side of the screen appear. For example, in Figure 2.3 a high-level “data” tab has been selected and the learner can then select subordinate left tabs linking to different sources of data such as the financial data shown in this screen shot.

A menu-driven approach could be useful when multiple resources or scenario perspectives are available and you want to allow the learner the freedom to select from among those before making a decision or taking action. Menus offer an intermediate level of learner control—more than the branched scenario but less than the full-screen design described in the next paragraph.

Full Screen Active Object

In Figures 1.1 and 1.2 I showed troubleshooting training situated in a virtual automobile repair shop. This approach has a game-like interface with multiple on-screen objects for the learner to explore. The active object interface potentially offers a high degree of learner control and in fact could lead to confusion and mental overload for an entry-level worker. However, if your instructional outcome involves learning an optimal (efficient or logical) sequence of activities, learners will need an interface that gives them freedom to enact different sequences. This interface could work well for some compliance, diagnostic, research, tradeoffs, and operational goals.

Virtual Worlds

In Figure 2.4, I show a virtual world interface for a sales training class. Just as in in-person classes, the learner in the form of an avatar is free to generate her own responses and move around the 3D space at will. In contrast to the branched scenario, which offers limited choices, or the menu design, which offers several defined choices, here the learner exercises much higher degrees of freedom. Virtual worlds could offer a useful alternative to a face-to-face classroom for role plays or for design projects—especially for designs that involve manipulation of three-dimensional objects. From a visual perspective, obviously the virtual world provides opportunities to engage with three dimensional objects. However, many skills could be learned as effectively in a two-dimensional environment such as the automotive shop described in the previous paragraph. You will need to consider when the extra fidelity of a third dimension along with high levels of learner freedom will best serve your desired learning outcomes.

Although technology may overcome current limits, three-dimensional learning environments require specialized technical skills and digital resources. Based on an informal survey of my colleagues, as of the writing of this book, virtual worlds are not predominant learning environments. For example, one colleague has found two main barriers to implementing virtual worlds, including the high cost of development due to expensive technology and, secondly, the majority of learners (unfamiliar with 3D worlds) are challenged with the additional mental load of navigating and responding in a new environment.

MEET THE SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING SAMPLES

I am very grateful to my colleagues who have given permission to include screen shots from their excellent courses to illustrate this book, as well as to Mark Palmer, who worked with me to design the Bridezilla lesson. Although I have included quite a few examples throughout the book, I have relied primarily on seven courses. You can see an orientation to each course in the back of this book in Appendix A. In addition, you can find screen shots from these courses organized in the sequence in which they appear in the book as well as organized by course in a logical learning sequence online at Pfeiffer.com/go/scenario. Password: Professional.

COMING NEXT

By this stage you should be forming some ideas as to the kinds of instructional challenges you face that might benefit from scenario-based e-learning. Now it’s time to consider your design. In the next chapter I offer a bird’s eye view of a design plan for a scenario-based e-learning lesson to be followed by expanded discussions of each component in the chapters to follow.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Kapp, K.M., & O’Driscoll, T. (2010). Learning in 3D. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

This book focuses on effective use of virtual world technology for learning and instruction.

Leighton, J.P. (2011). A cognitive model for the assessment of higher order thinking in students. In G. Schraw & D.R. Robinson (Eds.), Assessment of higher order thinking skills. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

See this chapter for a more detailed and technical discussion of a taxonomy of the critical thinking skills I summarize in Table 2.1.