CHAPTER 7

PUTTING THE “L” IN SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING

In Chapter 6 I reviewed some design techniques to build in guidance (often referred to as scaffolding) for guided discovery learning environments. The main goal of guidance is to keep the learners on the right track as they work the scenario. One form of guidance I describe separately in this chapter involves instructional resources. There is a fine line between techniques for guidance and instruction. Regarding instructional resources, I emphasize techniques that are explicitly designed to teach knowledge and skills at the right time to help the learner make a decision or take an action. Since the ultimate goal of each scenario is to promote learning of specified knowledge and skills in the context of solving a problem, you need to consider the type of and format for instructional resources. Instructional resources can precede or be embedded in the scenario—or both. Some of the more common instructional strategies include tutorials, instructors, references, examples, and social media knowledge resources.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

Which of the following statements do you find true regarding instructional resources in scenario-based e-learning? I’ll offer my opinion on each at the end of the chapter.

INTEGRATING KNOWLEDGE AND SKILL RESOURCES

As an experienced instructional professional, you are most likely familiar with how to design job-related knowledge and skill training based on your learning objectives and the background of the learners. When you defined your scenario outcomes in Chapter 4, you specified your terminal learning objective. As you consider your scenario outcomes and their associated knowledge and skills listed in Table 2.1, you can also write the enabling or supporting objectives to serve as milestones to the final goal. In Table 7.1, I list some typical enabling knowledge and skills based on the terminal objectives presented in Chapter 4. These objectives need not be displayed to the learner, but will be useful to guide the design and development of the lessons. Having defined your learning goals—both major and supporting—you can consider the when, what, and how of instructional resources to include in your instruction.

TABLE 7.1. Some Sample Terminal and Enabling Learning Objectives by Domain

| Learning Domain | Sample Terminal Objective from Table 4.1 | Sample Enabling Objectives |

| Interpersonal Sales Customer Service Management | Given a respondent, learner will select or generate optimal statements to achieve task goals. | Review respondent history and identify features relevant to outcome goal. Explain relevant information tailored to respondent needs or situation (product specs, policies, processes). Anticipate and respond to questions or objections. Offer a solution or follow-up plan. |

| Compliance | Learners will respond to situations by taking actions congruent with organizational policies and procedures. | Identify actions or statements as congruent or in conflict with organizational or legal policy. Locate/identify specific applicable policies or laws. Select action or decision aligned to policy or legal requirements. |

| Diagnosis and Repair | Given symptoms and testing options, learner will apply efficient diagnostic process to select tests, interpret results, and make a repair. | Identify failure symptoms. Define potential hypotheses. Identify which tests are most appropriate for hypotheses. Interpret results from tests. Narrow potential causes. Justify diagnosis with rationale. Perform repair/treatment and monitor results. |

| Research, Analysis, Rationale | Given an assignment and sources of case data, learner will apply efficient research process to select data, interpret results, and make a decision and/or produce a product. | Based on assignment, identify relevant resources. Search, access, and interpret data. Rate data based on relevance to or impact on research goal. Make decision congruent with data. Justify decision with appropriate rationale. |

| Tradeoffs | Given a business goal or dilemma, learner will identify and evaluate various perspectives to make and justify a decision. | Identify alternative responses to dilemma. Review perspectives on the issue. Identify pros and cons on decision or action alternatives. Justify decision made or action taken. |

| Operational Decisions | Given equipment interfaces and relevant data, operator will adjust controls to optimize outcomes. | Interpret signals from interface. Gather and interpret additional relevant data. Identify equipment process likely underlying signal. Form hypothesis as to cause of abnormal signals. Prioritize operational goals. Respond to remedy situation. Monitor and repeat process as needed. |

| Design | Given requirements and resource data, learner will construct a product that optimizes resources and meets requirements. | Gather and interpret project constraints. Gather and interpret design criteria. Review previous product solutions. Select or create prototype. Test prototype. Interpret test results. Revise prototype based on test results. |

| Team Collaboration | Given a goal requiring a collaborative synergy among team members of diverse expertise, learner will ensure effective team communication, make decisions, and take action to optimize outcomes. | Assess desired outcomes or team goal. Assess team resources and constraints. Apply communication model to optimize team resources. Prioritize team alternatives. Coordinate team activities based on team input. Monitor and adjust as needed. |

Regarding the when, you may determine that a standard tutorial (either in an instructor-led or multimedia environment) should be offered prior to the scenario-based learning lessons or embedded as a resource to be accessed within the scenario interface—or both. Recent evidence I review in Chapter 10 suggests situations that benefit from tutorials provided before problems as well as tutorials provided after problem solving. Regarding the what, you may opt for several instructional resources drawing from the suggestions in this chapter. Regarding the how, you may need to decide whether to:

In the next paragraphs I will review the most common instructional resources, including tutorials, reference, examples, and instructors.

TUTORIALS

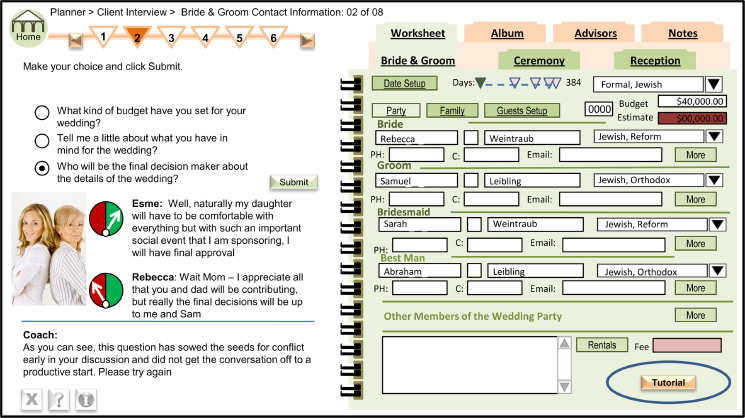

As instructional professionals, I assume you are experienced creating basic tutorials to teach procedures or concepts linked to work-relevant tasks. In fact, you may even have access to some relevant tutorials related to your scenario-based e-learning goals in your organization’s training repository. Your main challenge in scenario-based e-learning will be to first locate, create, and segment tutorials that support required knowledge and skills needed to resolve the scenario and then decide how you want to link them to your interface. One approach is to review the different elements in your design plan in terms of their visual representations. For example, you may want to construct tutorials linked to the on-screen objects representing sources of case data to help learners know whether a specific object is relevant to a specific case and how to interpret data from it. If you have designed a worksheet as a support tool, you could provide links to tutorials on each major element of the worksheet. For example, the Bridezilla lesson includes three worksheets. A short procedural tutorial on each worksheet can be accessed by clicking the lower-right tutorial button, as shown in Figure 7.1.

FIGURE 7.1. Clicking on the Tutorial Button (Lower Right) Leads to a Short Demonstration on Completing the Form.

Alternatively, if you have used a menu to represent the major elements of your design or stages in the workflow, you could add specific links for tutorials associated with menu items. Another option is to add on-screen objects to serve specifically as repositories for tutorials, such as books, computer screens, or even a virtual office wall poster with some type of process graphic on it.

In a simple implementation, learners can access tutorials on demand. In a more sophisticated approach, tutorials can be assigned or advised based on a tracking of the actions of the learner in the scenario. For example, in the automotive troubleshooting scenario, if one or more inappropriate tests are selected, a brief tutorial on diagnosing the specific type of fault in the scenario could be offered by the tech support telephone line or by an on-screen coach.

REFERENCE

Consider embedding references into your scenario interface. If you are lucky, there are existing references available. For example, the automotive troubleshooting scenario was able to take advantage of pre-existing online technical manuals on the various systems unique to each automotive make and year. By clicking on the on-screen computer in the auto shop, the corporate intranet reference menu appears, as shown in Figure 7.2. Clicking on the service manual opens it to a list of parts or systems, which in turn lead to specific schematics or descriptions of each element.

FIGURE 7.2. The Computer in the Virtual Auto Shop Links to Technical References.

With permission from Raytheon Professional Services.

If you don’t have pre-existing reference resources, it’s common practice to develop them as part of any instructional effort. For example, in a compliance scenario, an online book can open to relevant policy statements. In a sales scenario, online references can summarize product features and benefits. If your scenario will focus on a process, consider a poster displayed prominently on the workstation wall illustrating a high-level graphic summary of the stages. Clicking on any stage on the poster zooms into more detailed explanations.

As with any instructional effort, as you review your learning objectives, ask yourself: “What memory support would be useful here?” “What facts or steps would be needed to achieve the goal?” “Are there pre-existing references we could repurpose?” If not, what kinds of references would you want to include and what would be the best way to represent them?

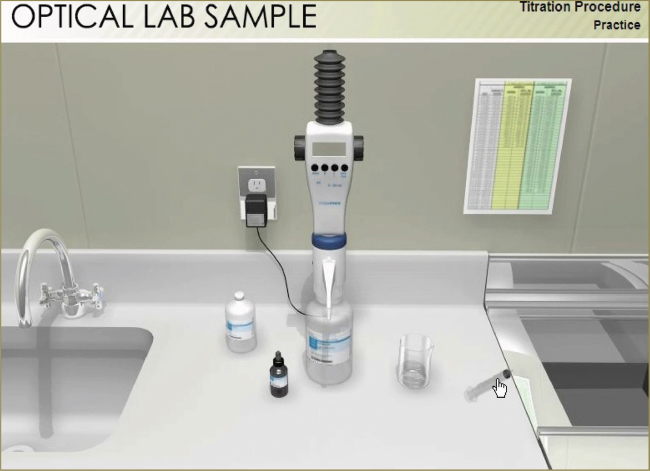

Keep in mind the need for visual contiguity. If the learner has the opportunity to open a reference resource, avoid covering up your interface with the resource or find a way to make that resource information easily accessible when it is closed. For example, a relevant procedure could be printed out or a procedure window minimized. Alternatively, a relevant resource could be copied and pasted into a persistent on-screen area such as a clipboard or file that could drop down as a small window that does not obscure the action field. In the laboratory simulation shown in Figure 7.3, the learner refers to a wall chart that summarizes the correct reagent dilution proportions to achieve a desired concentration. When clicking on the wall chart, a zoom effect magnifies its contents.

FIGURE 7.3. A Wall Chart Provides a Reference for a Laboratory Procedure.

With permission from Raytheon Professional Services.

EXAMPLES

I have found examples to be underutilized in the scenario-based e-lessons I have reviewed. A lack of examples is a missed opportunity for support, as they are a well-proven, powerful learning aid. An example might take the form of a behavioral model in which a video or animated “expert” demonstrates how best to respond to a similar problem, as shown in Figure 6.4. Alternatively, examples may take the form of stories. Experts are famous for swapping war stories of challenging and memorable situations they have faced (Green, Strange, & Brock, 2002). In fact, much expertise is based on a repository of examples indexed in memory in a way that facilitates retrieval when facing a problem with similar features. It’s not uncommon to hear experts talking over breaks or at lunch with phrases like: “Yeah–I remember a case I had like that once. At first I thought. . . .”

As you plan examples, consider the format, the type, the focus, and how examples might be accessed. Do you need to provide an example illustrating an entire solution process to a problem similar to the one the learner is assigned? This could be accessed by a “show me” button that activates a step-by-step demonstration of how a similar scenario was resolved. Alternatively, you could plan mini-examples linked to specific elements of your scenario. For example, if your lesson incorporates a number of objects, such as various testing equipment that could be used to diagnose a failure, you could link an example to each test individually. Each example would consist of a brief commentary from an expert describing when and why he or she has used that test in the past.

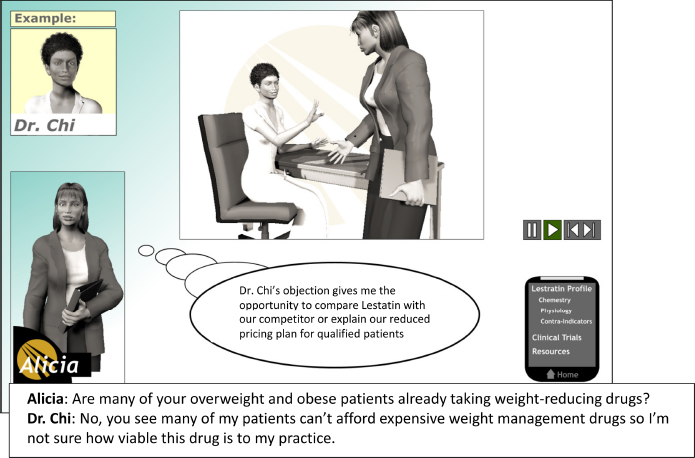

To help build critical thinking skills, consider a specific type of example called a cognitive modeling example. In a cognitive modeling example, the expert illustrates what he or she did, but also describes the rationale or mental heuristics. In Figure 7.4 the expert sales representative demonstrates not only her actions but also her thoughts. Multimedia is an excellent tool for making tacit knowledge explicit during a demonstration of expert performance.

FIGURE 7.4. A Cognitive Modeling Example Illustrates Not Only the How But Also the Why.

You might consider building a repository that offers examples indexed to the actions, decisions, or rationale of your scenarios. If your organization has a repository of examples as part of its knowledge base, exploit it by cross-indexing related examples into your course. For example, the Bridezilla course uses a virtual album as a repository of examples. Each wedding example in the album includes photographs, client reviews, and a budget summary.

Research on examples has shown that, for building critical thinking skills in a domain, offering several examples in which the specifics vary somewhat but the underlying principles remain the same is a more effective approach than providing only a single example or two examples with the same surface features. As you collect multiple examples, consider a repository that indexes examples to the scenario categories or elements.

Make Examples Engaging

One drawback to examples is that learners fail to process the example deeply or may even bypass it completely. Overcome this potential stumbling block by adding questions to your examples—questions that force the learner to carefully review and process the example. For example, in Figure 6.4, the learner views an expert modeling the optimal response to a client’s objection. The multiple-choice question prompts the learner to carefully study the example. Research has shown that adding questions to examples yields better learning than when the same examples are included without questions.

INSTRUCTORS

Will your scenario-based e-learning be facilitated by an instructor—either online or in a face-to-face learning environment? If so, consider what roles that instructor might serve. In some cases, the instructor might actually play a role in the scenario. For example, he could play the role of the client, the project manager, or even inanimate objects such as equipment. In a troubleshooting class, teams review the symptoms and suggest what test they would try first. The instructor, assuming the role of the equipment, displays the results of a given test and asks the learners to interpret the results and decide whether that test was appropriate and what they learned from it. Next moving into a more traditional role, the instructor could suggest alternative actions he would take commenting on the team’s choices.

Alternatively, the instructor may focus more on the problem-solving process than on the outcomes. In this role, the instructor models and monitors the critical thinking process stages. For example, if individuals or teams are problem solving, the instructor could ask questions such as “What are you doing now?” “What other alternatives did you consider?” “How will you know whether your current activity is moving you forward in solving the problem?”

Give Your Learners an Instructional Role

In my e-learning design course, participants tackle an assignment in several rounds. They initially work in teams for about an hour to produce a prototype product—a storyboard. Next, the instructor provides background knowledge for all participants, who are then individually assigned to a specialized content area to research. For example, some research best practices relevant to use of visuals, to use of audio and text to describe visuals, or to navigational facilities. Each participant then gives a mini-tutorial to others on his or her area of expertise. After the teach-back sessions, teams revisit their projects to evaluate what they created initially and to revise it based on new knowledge.

In sum, as you consider your desired outcomes, define the role of the instructor. Should she serve as an expert practitioner providing domain-specific instruction to correct misconceptions or advance thinking? Should she play the role of a critical thinker ensuring a logical train of thought and domain-specific problem-solving approaches? Should she assume the role of the object of the scenario, such as the equipment or patient, or test response to a selected action? Should she emphasize thinking process behaviors guiding students to identify, discuss, and refine their own learning with minimal instructional input? Many of these roles are quite different from traditional didactic activities and instructors habituated to such a traditional role will likely need support in transitioning to new activities.

WHAT DO YOU THINK? REVISITED

Which of the following statements do you find true regarding instructional resources in scenario-based e-learning? Here are my thoughts:

COMING NEXT

Now that you have addressed techniques to minimize the flounder factor and to support learning, it’s time to consider two final essential elements: feedback and reflection. As the learner responds to the scenario, she needs at some point to know whether she has made appropriate selections. Further, she needs to step back, review her thoughts and actions, and consider what worked well and what needs improvement. No scenario-based e-learning lesson can fully achieve its goals without these two critical elements.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Renkl, A. (2011). Instruction based on examples. In R.E. Mayer & P.A. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of research on learning and instruction. New York: Routledge.

A very comprehensive and somewhat technical review of research on examples in learning environments.

Schank, R.C., & German, T.R. (2002). The pervasive role of stories in knowledge and action. In M.C. Green, J.J. Strange, & T.C. Brock (Eds.), Narrative impact: Social and cognitive foundations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

This book reviews the key roles that stories play in shaping our memories, knowledge, and beliefs.

| Enabling Objective | Instructional Alternatives | How to Implement/Represent |

| EO 1 | Tutorials | Reference |

| Pre-existing | ||

| To be developed | ||

| Examples | ||

| Expert solution demonstrations | Questions in demonstrations to promote engagement | |

| Cognitive modeling examples to illustrate tacit knowledge | ||

| Example repositories linked to organizational knowledge base | ||

| Instructors | Traditional role | |

| Socratic role | ||

| Scenario role | ||

| EO 2 | Tutorials | Reference |

| Pre-existing | ||

| To be developed | ||

| Examples | Expert solution demonstrations | |

| Questions in demonstrations to promote engagement | ||

| Cognitive modeling examples to illustrate tacit knowledge | ||

| Example repositories linked to organizational knowledge base | ||

| Instructors | Traditional role | |

| Socratic role | ||

| Scenario role |