CHAPTER 8

DESIGNING FEEDBACK AND REFLECTION

Imagine you are taking a lesson on diagnosing and treating a sick cat. You have access to the owner’s description of symptoms, your own examination results, as well as data from various tests you ordered. You begin by reviewing the data, then ordering and interpreting test data, and, finally, selecting a treatment plan. However, you receive no response to your selections. You don’t know whether the cat died or improved. You don’t know whether you ordered the right tests or whether you interpreted them correctly. In fact, you don’t know much more at the end of the episode than you did at the start. Imagine, in contrast, that after you make a treatment decision, the clock fast forwards, and you see a healthy cat and happy owner twenty-four hours later. You can be satisfied that your decisions were appropriate, but you still might wonder why. You see the consequences of your actions, but perhaps have not learned the reasons for your success—or a more efficient, less expensive way to solve the problem. Detailed feedback on your solution, your problem-solving process, and your rationale makes all the difference between an effective and an ineffective learning experience.

THE POWER OF FEEDBACK

Among experimental research studies comparing the efficacy of various instructional methods, feedback gets a high score. Based on a review of twelve meta-analyses, Hattie and Gan (2011) found the average effect size for feedback was .79, which is twice the average effect size of other instructional methods. An effect size of .79 means that, given feedback, learners will average about eight-tenths of a standard deviation higher scores on an assessment than learners not given feedback.

The bad news is the high variation of effects noted among all of the experiments. In some experiments feedback diminished learning. According to Kluger and DeNisi (1996), one-third of all feedback in the studies they reviewed actually depressed learning! From the research we have learned that feedback has huge potential to improve learning, but not all feedback is effective. In this chapter I will look at the unique forms of feedback you can design into scenario-based e-learning and offer guidelines you can adapt to your instructional context.

LEARNING FROM MISTAKES

Are mistakes good or bad for learning? Following a disastrous collapse in the final round of the 2011 Master’s golf tournament, Rory Mcillroy commented: “It was a very disappointing day, obviously, but hopefully I’ll learn from it and come back a little stronger. I don’t think I can put it down to anything else than part of the learning curve” (downloaded from The Telegraph, June 22, 2011). Anyone who watched his record-breaking win just two months later at the U.S. Open witnessed first-hand the potential of mistakes to shape and improve performance.

Directive courses, reflecting their behaviorist roots, are designed to minimize errors. If a mistake is made, the learner receives immediate corrective feedback. For example, if an incorrect formula is entered in an Excel lesson, instructional feedback immediately displays a message such as: “Remember to use the ‘*’ operator when you need to multiply.” Behaviorist psychology applies the premise that incorrect responses, if not immediately corrected, can embed the wrong knowledge and skills in memory. Mistakes are to be avoided and, when they occur, are to be immediately remedied. In contrast, scenario-based learning makes different assumptions—mainly that mistakes can provide a useful learning experience. In fact, sometimes the most memorable lessons learned are those born from errors.

You can probably identify some lessons learned from your own mistakes—big or small. Recently, during my Italian lesson I wanted to say that I was disgusted with a particular situation. Instead, I said that I was disgusting. Fortunately, the instructor stopped me immediately and explained the differences—disgustoso meaning disgusting and disgustata meaning disgusted. This was such a memorable mistake that I am unlikely to ever make it again—thanks to immediate feedback from the instructor.

INSTRUCTIONAL VS. INTRINSIC FEEDBACK

In scenario-based e-learning training design you have multiple feedback opportunities. You can include both instructional and intrinsic (consequential) feedback. With intrinsic feedback, the learning environment responds to decisions and action choices in ways that mirror the real world. For example, if a learner responds rudely to a customer, he will see and hear an unhappy customer response. Intrinsic feedback gives the learner an opportunity to try, fail, and experience the results of errors in a safe environment.

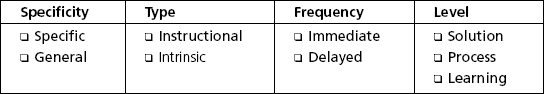

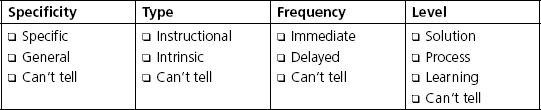

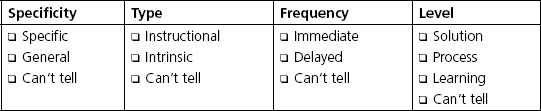

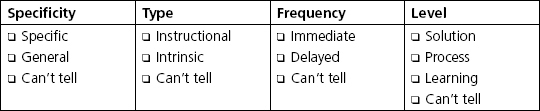

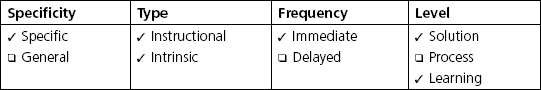

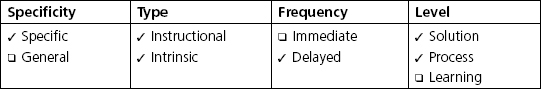

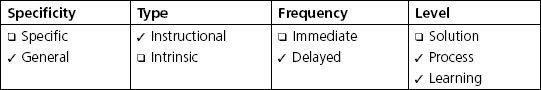

In this chapter I will provide guidelines for feedback targeted at three major levels: scenario solutions, problem-solving processes, and learning needs. Additionally, to ensure that learners process the feedback provided, you can require learners to reflect on the feedback and draw conclusions from it. In this chapter I will discuss several important feedback parameters for you to consider in your design, including:

- Specificity: general to focused

- Type: instructional and intrinsic

- Frequency: immediate or delayed and,

- Focus: solution, process, or learning needs

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

Read the feedback provided in each scenario and indicate whether it is (a) specific or general, (b) instructional, intrinsic, or both, (c) immediate or delayed, and (d) focused on solutions, process, or learning needs. My answers appear at the end of this chapter. If you would rather do the exercise after reading the chapter, move on to the next section.

FEEDBACK IN A NUTSHELL

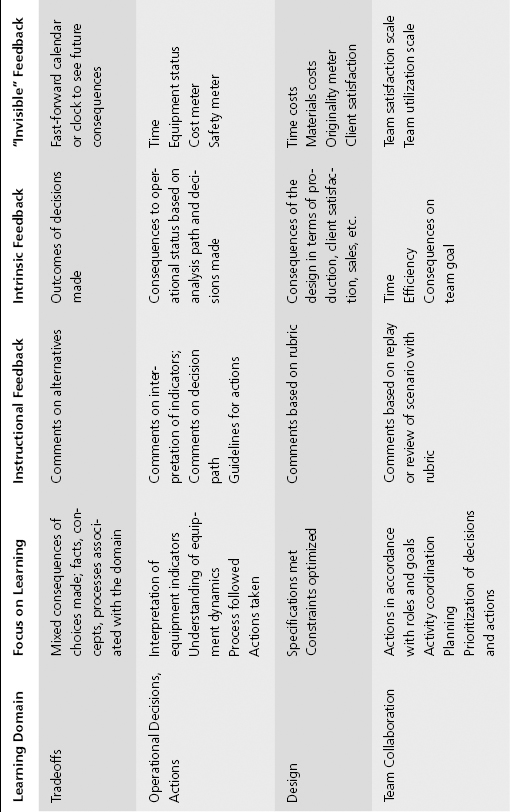

Based on evidence and the design opportunities inherent in scenario-based e-learning, I will describe some guidelines for feedback which are summarized in Table 8.1.

TABLE 8.1. A Summary of Feedback Features

| Feedback Feature | Alternatives | Comments |

| Specificity | Specific or General A. Conduct the sss test (specific) B. You are not using the best test for this situation (general) |

Specific feedback is more helpful and also more expensive to produce. |

| Type | Intrinsic and Instructional A. Customer frowns (intrinsic) B. You should have asked an open-ended question (instructional) |

Intrinsic feedback requires a realistic environmental response to learner actions. Instructional feedback can explain the reasons for the outcomes and suggest alternative actions to consider. |

| Frequency | Frequent or Delayed Feedback could be given with each learner response, at the end of a segment, or at the end of the lesson. |

Frequent feedback imposes more guidance; delayed feedback might be better for process-focused scenarios. Consider your learning goals and background knowledge of your learners |

| Focus | Level 1—correctness of solution Level 2—solution process Level 3—learning or problem-solving gaps; recommendations for additional learning resources |

Level 1: Useful, especially for highly structured problems with right or wrong answers Level 2: Useful when the learning goal focuses on the problem-solving process Level 3: Useful if the program can make valid inferences about knowledge gaps as the basis for additional training |

1. Be Specific

In general, evidence shows that more specific feedback leads to better learning than generalized feedback. For example: “You need to rule out electrical malfunctions in the drive shaft” is more helpful than “It looks as if you are not following the correct solution path.” Feedback that not only tells learners whether they are right or wrong but also gives a brief explanation has proven to lead to more learning than feedback that simply states “right” or “wrong.” Of course, more specific feedback takes more time to construct, so you will need to consider the cost-benefit tradeoffs. In particular, you may decide to offer specific feedback linked to some actions and more generalized feedback in other places where specific feedback would not be cost-beneficial.

2. Provide Intrinsic and Instructional Feedback

As an experienced instructor, you are familiar with instructional feedback. In instructional feedback, commonly known as corrective feedback, you give information about the accuracy of a solution, along with an explanation. One of the unique opportunities of scenario-based learning lies in intrinsic or consequential feedback. In intrinsic feedback, the learner takes an action or makes a decision and experiences the results of that action. For example, in the customer-service branched scenario example in Figure 6.1, with each response the learner makes to the customer, she can hear and see the customer’s reply. In addition, she will hear instructional feedback from the virtual coach in the bottom left portion of the screen.

Multimedia can be designed to incorporate “invisible” forms of intrinsic feedback. For example, we used an attitude meter to show how the mother and bride-to-be are responding to each statement made by the wedding planner. Other examples I’ve seen include a money bar chart or scale illustrating income and outflow over time as decisions are made, a germ meter reflecting levels of contamination based on actions taken, and a virtual clock used to accelerate the passage of time.

In general, I recommend that you incorporate both intrinsic and instructional feedback into your lessons.

3. Adjust Feedback Frequency Based on Guidance Needs and Learning Goals

In a branched scenario, similar to the lesson shown in Figure 6.1, feedback—both instructional and intrinsic—appears with every learner selection. Immediate feedback on each action provides a high level of guidance and is most appropriate for novice learners. In contrast, if the goal of your scenario is to teach a troubleshooting or problem-solving process, immediate feedback on each action might not give the learner sufficient latitude to learn from inefficient or ineffective paths. For example, in the automotive troubleshooting course, feedback is delayed until the learner selects a failure. As a general guideline, I recommend you provide more frequent feedback in initial scenarios intended for novice learners and delay feedback in more advanced lessons.

4. Focus the Feedback Based on Your Goals

Kluger and DeNisi (1996) reported that a large proportion of instructional feedback did not improve learning—and in some cases even depressed learning. Evidence shows that feedback that focuses the learners’ attention to themselves hinders learning. For example, feedback that incorporates praise (“Great work!”) or gives comparative scores (“You’re in the top 10 percent!”) tends to draw attention to the ego and away from the learning task. Instead, you should focus feedback onto the task in general and the gap between the outcome criteria and the learner’s achievement in particular.

Based on an analysis by Hattie and Gan (2011), I recommend three levels of feedback: (1) solution focused, (2) task-process focused, and (3) learning focused. Which combination of these you provide will depend on your instructional goals. If the goal is relatively bounded, for example, a correct application of corporate compliance policies, instructional feedback may simply state whether the learner’s response is correct or incorrect and give a reason based on the policies. If the learning goal involves a problem solving process that requires research, analysis, and decisions, both solution and task-process focused feedback will be helpful. For example, in Figure 8.1 the service technician can compare her solution process with an ideal solution shown on the left. Finally, you may also want to provide learning feedback that directs the learner’s attention to his or her personal instructional needs. For example, if the learner is floundering in selecting a logical progression of research or testing options, the program could offer a tutorial addressing specific knowledge gaps.

FIGURE 8.1. A Summary of the Learner’s Actions (on the Right) Is Displayed Next to an Expert Solution Process (on Left).

With permission from Raytheon Professional Services.

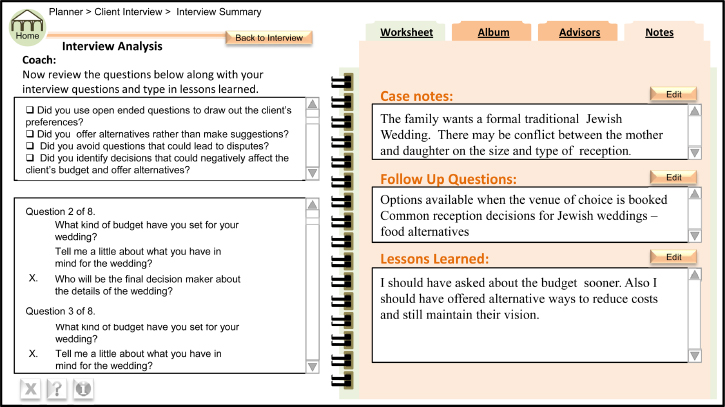

Embed Reflection Opportunities for Learners

As you design your program, keep in mind not only the feedback you offer, but whether or how that feedback is received by the learner. Often learners give feedback only a cursory review. They might look at the overall outcomes of their solution responses but not really consider what they have learned and how they might respond more effectively next time. I recommend that you find ways to encourage reflection on feedback. In a self-study environment, you might provide an end-of-lesson window that asks learners to input how they would approach a similar situation differently. For example, in Figure 8.2 at the end of the wedding planning interview, learners can review their questions and use the checklist on the left side of the screen to evaluate themselves. Input boxes on the right offer a place for the learners to document follow-up questions and lessons learned. Alternatively, learners can review their outcomes and construct an action plan focusing on future developmental efforts.

FIGURE 8.2. Response Windows (on the Right Side of the Screen) Encourage Learners to Reflect on Feedback.

FEEDBACK AND REFLECTION IN LEARNING DOMAINS

I’ve given some brief and general guidelines on feedback, and those may be enough for your needs. In the next section, I’ll consider how these guidelines might be applied to several of the learning domains we’ve discussed throughout the book. I summarize some ideas in Table 8.2 and will elaborate on each, along with some examples. At this point you may want to use the following section of the chapter as a reference by reviewing specifically the learning domains most relevant to your context.

TABLE 8.2. Some Feedback Options by Scenario Domain

Interpersonal Skills

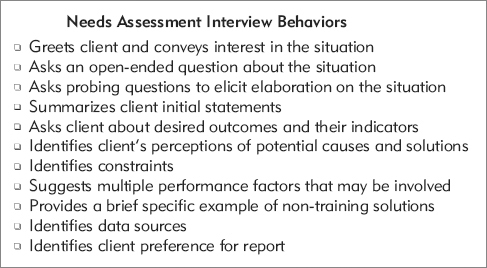

As we saw in Figure 6.1, you can make interpersonal skill training highly guided by offering a combination of intrinsic and instructional feedback with each response. In contrast, you may opt for a less guided experience in which the learner will make several statements or responses before receiving feedback. Intrinsic feedback can be represented with respondents’ body language, replies, or an attitude meter. If instructional feedback is delayed for several learner responses, the attitude meter can offer intermediate intrinsic feedback, giving the learner clues about the general effectiveness of her choices. In the most open interpersonal skills design, learners respond in a role play—often with another class participant or the instructor playing the role of the client. In this situation, the interactions can be recorded and replayed, with feedback given by peers, the instructor, and/or actual clients (compensated for their participation). Feedback to very open responses should be focused with a checklist to provide structure. In Figure 8.3 you can review a checklist for a needs assessment interview. When constructing checklists, write observable behaviors based on an analysis of top performers. Reviewing samples and giving feedback promotes not only learning of the individual performer but also of those giving the critiques.

FIGURE 8.3. A Feedback Checklist for a Needs Assessment Interview Role Play.

Compliance

In designing scenario-based e-learning for compliance purposes, you can decide how much guidance is appropriate for the policies to be reviewed as well as for the learners. You may decide to stick with relatively clear-cut applications of organization policies and procedures. A branched scenario design includes a situation (described in text or illustrated with still or animated graphics), three or four response options, and instructional feedback for each. In a more complex version, you may provide sources of case background information, such as an employee file, an employee interview, or a worksheet. Instructional feedback may suffice. However, you may also want to add intrinsic feedback such as a fast-forward clock and an animation illustrating the adverse consequences of policy violations.

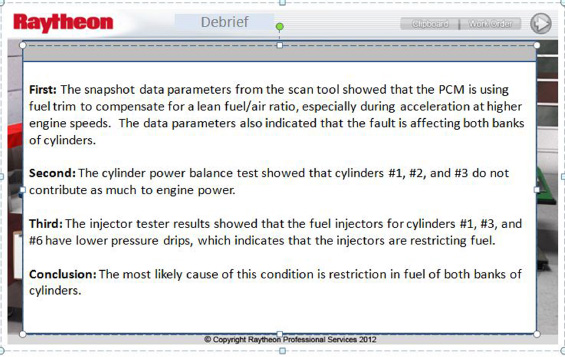

Diagnosis and Repair—Research and Analysis

I’m combining these domains since the critical thinking skills in both typically involve reviewing and assessing the initial state or request, identifying supporting data needed, interpreting that data, and making a decision based on the interpretation. We discussed guidance options in Chapter 6 and, based on those decisions, you can adjust your feedback accordingly. At some point in the learning progression, you will need to give learners freedom to identify and interpret different sources of case data. In these situations you may want to provide feedback only after the learner makes a repair or treatment decision. It will be important to give solution feedback (instructive and intrinsic), as shown in Figure 8.4, as well as process feedback, as shown in Figure 8.1. To ensure maximum value from that feedback, add a structured reflection interaction as well. In general, for these domains I recommend feedback that is specific, intrinsic, and instructional, and somewhat delayed with a focus on solution, process, and learning needs.

FIGURE 8.4. Instructional Feedback for the Automotive Repair Scenario.

With permission from Raytheon Professional Services.

Tradeoffs

In tradeoff scenarios, there is often no single correct answer. Intrinsic feedback is used to show a realistic potential outcome from any decision made. Each choice will have an outcome with a combination of desirable and undesirable features. For example, you may have improved sales, but the cost of your solution outweighs financial gains. Or you may have made the bride happy but upset the bride’s mother, who is paying for the wedding. Additional learning can be promoted by instructional feedback that comments on the decisions made. For example, next to the spreadsheet showing improved sales but increased costs, the coach may comment on ROI, discussing factors to consider when taking actions to improve sales. In tradeoff scenarios, the goal is to review different perspectives on a problem and the advantages and disadvantages of each. The feedback is typically not corrective and may not be overly concerned with process. After the learner completes a segment of the scenario, you may ask some reflection questions such as those shown in Figure 8.2, followed by an option to reconsider the decision or rerun the scenario.

Operational Decisions

In most operational scenarios, intrinsic feedback plays a major role. As the learner takes an action, the environment responds as it would in the actual equipment. Based on the new environmental state, the learner makes further adjustments. Consider the opportunity to augment visible intrinsic feedback with some invisible indicators as well. For example, in a power plant, changing the control settings will be reflected on equipment gauges, but you could also add an internal view of the equipment or an indicator of costs per hour as a source of normally invisible feedback.

Design

By definition, design products are open-ended. There are usually multiple correct outcomes in the form of products or solutions that meet requestor needs and environmental constraints. In a self-study environment without instructor support, feedback can be provided in the form of sample products for the learners to compare with their solutions. The feedback can provide the learners with a checklist to guide and structure their comparison. Naturally, this type of review can also make a useful collaborative exercise with peer or team input. Because of the open nature of the outcome, feedback may be less specific. If there are intermediate stages in product design and development, feedback can be attached to each, allowing adjustments along the design path. If an instructor or client representative is available, tailored feedback can come from these sources as well. For example, at one pharmaceutical sales training site, compensated doctors gave feedback to sales presentations.

Team Coordination

If your focus in a team coordination lesson is on communication and coordination actions an individual might make in a team setting, you can provide feedback on those individual decisions similar to previous domains we have discussed. However, if your environment allows for multiple simultaneous decisions among team members, you may want to keep a record of the various decisions made and replay or review them as a extended debriefing with a discussion of lessons learned. For example, in a military simulation, the exercise is video recorded and replayed with a discussion debrief. As mentioned previously, for more open-ended environments use a checklist of optimal behaviors to focus feedback.

WHAT DO YOU THINK? REVISITED

Take a minute to review the answers you entered at the start of the chapter. Keep in mind that your assumptions might be different from mine and we can both be correct in our analysis.

The feedback descriptions I provided in the previous exercise were brief, so if you made different decisions regarding the features of the feedback, don’t worry. In your own domain you will have a clearer and more comprehensive idea of the scenario outcomes and the types of feedback to provide.

COMING NEXT

This chapter completes my discussion of the core elements of a design model for scenario-based learning lessons. As you have seen, quite a few resources can go into creation of lessons using a guided discovery approach. Before making such a commitment, you may wonder whether your efforts will pay off. The next two chapters will address evaluation techniques and outcomes from guided scenario learning designs. In Chapter 9, I review strategies you can use for your own evaluation—with an emphasis on evaluating learning. In Chapter 10 I summarize experimental research that has focused on guided discovery instructional environments.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning. New York: Routledge. See Chapter 9: The contributions from teaching approaches, part 1.

An interesting book that synthesizes volumes of research on instructional issues and provides guidance for instructional professionals. If you like data, this book is for you.

Hattie, J., & Gan, M. (2011). Instruction based on feedback. In R.E. Mayer & P.A. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of research on learning and instruction. New York: Routledge.

A recent evidence-based review of feedback effects. I found the second half of the chapter most relevant from a practitioner perspective.

Shute, V.J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 153–189.

A comprehensive and well-written review of research and application of feedback in instruction.