CHAPTER 9

EVALUATION OF SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING

Outcomes from scenario-based e-learning can be dramatic. For example, Will Interactive designed and developed a suicide prevention scenario-based e-learning course for the U.S. Army called Beyond the Front. The learner can assume the role of a soldier facing personal problems while deployed and/or the role of an officer overseeing soldiers exhibiting symptoms of depression. For example, in Figure 9.1, we see the negative emotional effects of a soldier discovering that his girlfriend is pregnant (not his baby!). Beyond the Front was required training for all active duty Army personnel. The following year Army suicide rates dropped 58 percent! While your training may not have life-or-death consequences, the outcomes can be just as profound. But without evaluation you will never know what effects your program has.

FIGURE 9.1. A Screen from Beyond the Front, Suicide Prevention Scenario-Based e-Learning.

With permission from Will Interactive.

When launching a new approach to learning—especially one that might be more expensive than previous courseware—the stakeholders usually want to know whether it’s working. That seemingly simple question can easily balloon into multiple evaluation questions. In fact, there may be more questions than you have the resources to answer. Some of the questions may be impractical or even impossible to answer in your context. There may be other questions that, once answered, won’t lead to any actions or decisions. Many evaluation questions will require some data gathering before the new training is deployed. For all these reasons, it’s a good idea to define and focus the evaluation questions sooner rather than later.

As evaluation questions are raised, ask yourself and your clients: “What will we do with this information?” For example, if we find that scenario-based e-learning is a more expensive approach, but is popular with learners, will we scrap the program for less-costly approaches or invest in a more popular approach? Where you receive an actionable response to that question, and the context and resources lend themselves to an evaluation project, put together an evaluation plan. When there is no real answer and/or the evaluation would consume too many resources or is unrealistic in your context, reframe or drop the question.

Early on, also consider whether you or your stakeholders want to compare the effects of scenario-based e-learning with a different (traditional or older) approach or whether you want to focus only on the effects of scenario-based e-learning. For example, if you have developed a new-product course in a traditional format, you might want to know whether using a scenario-based e-learning approach for similar learning objectives and content will cost more to design and develop, take learners longer to complete, and lead to higher student ratings, better learning, or better sales. Alternatively, your focus may not be a comparison with other training designs, but rather an evaluation of scenario-based e-learning on its own. Typical evaluation questions fall into any of five major categories: motivation, learning effectiveness, learning efficiency, transfer of learning, and return on investment. In Table 9.1 I summarize these categories, along with example indicators of each. Feel free to add to my list or adapt the indicators to your own context. In the first part of this chapter I will summarize strategies for evaluation within these major categories. Then I will devote the second half of the chapter to a discussion of how to use tests to evaluate learning from scenario-based e-learning courses.

TABLE 9.1. Some Typical Evaluation Questions for Scenario-Based e-Learning Courses

| Evaluation Category | Description | Typical Indicators |

| Motivation | Learner satisfaction with, engagement, and persistence in the training. | Student survey ratings Course completion rates Course enrollments when optional Social network ratings |

| Learning Effectiveness | Achievement of the learning objectives of the course. Usually measured with some form of test. | Tests measuring: Factual and conceptual knowledge Strategic or principle knowledge Near or far transfer procedural skills Near or far transfer open-ended skills |

| Learning Efficiency | The average time students take to complete the training. Time to achieve competency. |

Average time required to complete training Time to acquire expertise needed for competent job performance |

| Transfer to the Workplace | The extent to which new knowledge and skills are applied in the workplace. The extent to which scenario knowledge and skills are adapted to different contexts. |

Job performance metrics, such as sales, customer satisfaction Supervisor ratings Tests measuring use of skills in related but different context |

| Return on Investment | The ratio between performance gains in the workplace and costs to produce and take training. | Performance gains in workplace translated into monetary values divided by costs to design, produce, and deliver training multiplied by 100 |

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

Before we jump into the details, check off the statements below that you think are true about evaluation:

FOCUSING YOUR EVALUATION

Which questions will be of greatest interest to your stakeholders? Which questions could be readily answered using data already collected by the organization? How would you adapt evaluation questions to your context? What additional questions have not been raised by your stakeholders? Evaluations require a balance between value judgments and resources. Different organizations and even different contexts within an organization will have different values and diverse resources. Below are the most common questions you or your clients might ask about the outcomes of scenario-based e-learning courses.

Do the Learners Like It?

In some cases, motivation—that is, the satisfaction of your learners—is sufficient to support instructional product decisions. Some managers may feel that, if the learners see value in the training, that’s sufficient justification. Motivation is typically measured with student rating sheets completed during and after the training. Other sources of motivational data include comments and ratings on social networks, enrollment in similar courses, and course completion statistics. Indicators of student satisfaction may be all that your stakeholders need to sell them on the scenario-based e-learning approach. Design your motivation questions carefully. Research comparing test scores to responses on course evaluations found best correlation with questions asking the learners to assess their level of confidence (Sitzmann, Brown, Casper, Ely, & Zimmerman, 2008). An example question from the pharmaceutical sales course is: Rate your level of confidence in handling objections to Lestatin.

Is Instruction Effective?

Often, however, you will also need direct measures of instructional effectiveness—if for no other reason than to improve the instructional quality of your product. Comparisons of student course ratings with student test scores have shown almost no relationship (Sitzmann, Brown, Casper, Ely, & Zimmerman, 2008). Some learners whose test scores reflect minimal learning give the course high ratings, while others who achieved more give the course low marks. In other words, you can’t rely on participant ratings as accurate indicators of participant learning.

To assess learning objectively, you need some form of test. Since most scenario-based e-learning programs are targeted toward problem-solving skills, appropriate tests may be more challenging to construct and validate than tests you have developed in the past that measure conceptual or procedural knowledge. Tests that are not valid and not reliable are a waste of time at best, and misleading and/or illegal at worst. Therefore, you need to carefully plan your learning measurement goals, development, and validation processes. I will devote most of this chapter to guidelines on assessing learning from scenario-based e-learning courses.

Is the Learning Environment Efficient?

Instructional efficiency is another important metric, especially in organizational settings where staff is paid to attend training. Given two instructional programs with comparable learning outcomes, one of which requires twice as long for students to complete, the more efficient program may be the better choice—even if it is not the coolest or most popular option. Instructional efficiency can best be measured during the pilot stages of the training. By measuring and recording the time a small group of pilot students requires to complete the lessons, you can gain a reasonable estimate of efficiency. You may want to compare this efficiency estimate with time to reach similar instructional goals in a face-to-face classroom setting or online via a traditional training design. Be careful, however, to balance learning and efficiency metrics. For example, a face-to-face class may have required less time to complete but at the same time yielded either lower or inconsistent learning outcomes.

Does Learning Transfer?

Training transfer is an important outcome in organizations, where the goal is to improve bottom-line outcomes such as productivity, sales, efficiency, safety, regulatory compliance, etc. As you will see in the next chapter, in some experiments scenario-based e-learning resulted in better transfer of learning compared to a traditional part-task design. However, bottom-line productivity metrics reflect many factors, and it’s often challenging to claim a solid cause-and-effect relationship between training and job transfer.

In some situations, job metrics reflecting operational goals are routinely captured and, without too much effort, you could look at how these metrics might be affected by your training program. For example, in the suicide prevention course, suicide rate records are maintained by the Army, and it was easy to compare those rates before and after the training. Sales and customer service are two domains that routinely collect operational data. If you were going to use scenario-based e-learning to build optimal behaviors in customer service, you might be able to roll out the training in stages and compare job metrics, such as call monitoring data or customer complaints, between those trained first and others scheduled for later training. Alternatively, you might create two versions of the training—a traditional version that incorporates the core content of the scenario-based e-learning lessons as well as the scenario version—and compare metrics between the two groups. However, it’s often not practical to set up a true scientific comparison in an operational setting, so I recommend caution in making too many judgments (positive or negative) based on bottom-line metrics.

Is There a Good Return on Investment?

Basically, good return on investment (ROI) means that the tangible benefits accrued to the organization outweigh the costs to design, develop, and deliver the training. In terms of dollars, benefits are measured by cost savings, increased sales, increased customer satisfaction, fewer accidents, fewer audits, less employee turnover, more efficient work, and better compliance with regulatory requirements, among others. Time to reach competency is another potential benefit of scenario-based e-learning with ROI implications. For example, if automotive troubleshooting competencies that would require several weeks in a hands-on environment can be accomplished in several hours in a scenario-based e-learning environment, these time differences can be quantified. Along the same lines, scenario-based e-learning may reduce the amount of time spent in a face-to-face class, thus lowering travel expenses and other costs associated with in-person training.

To determine ROI, calculate the costs of the training and the monetary returns of the benefits. How you determine training costs is not always a straightforward process. It’s usually pretty easy to determine the resources in terms of time or dollars devoted to analysis, design, and development of a training program. However, you may also want to include the delivery costs—the instructor’s time and travel, the participant’s time and travel, facilities, administration, etc. To calculate the ROI, divide the net program benefits by the program costs and multiply by 100.

In many situations it is difficult to obtain bottom-line operational data that will reflect the benefits of training. I recommend considering a ROI evaluation when (1) training is targeted toward skills closely linked to bottom-line quantitative metrics, (2) relevant metrics are already being captured and reported by the business unit, and (3) your client is interested in ROI and is willing to devote the resources needed. Sales can offer a good opportunity. One organization developed a two-day instructor-led course for account representatives selling high-end computer products. The course focused on a process for sales staff to define customer needs and match products accordingly. Twenty-five account representatives were randomly selected to participate in the training, and for two months the following metrics were collected: number of proposals submitted, average pricing of proposals, average close rate, and average value of won orders. The data from the twenty-five trained staff were compared to twenty-five different randomly selected sales staff who did not attend training, and the outcomes were divided by the training costs to calculate a return on investment. They found the average close rate of trained sales staff was 76.2 percent, compared to 54.9 percent for untrained. By multiplying the close rate by the average value of won orders, dividing that figure by the training costs, and multiplying the result by 100 the research team determined an ROI of 348 percent (Basarab, 1991).

A recent report on the ROI from a coaching intervention asked hotel managers to set business goals and measure their achievement with the aid of an external business coach (Phillips, 2007). For example, several managers set goals of reduced turnover. As managers calculated the return on goals achieved, they multiplied that return by their own estimate of how much the coaching intervention led to that result. For example, if reduced turnover resulted in a savings of $50,000 and a manager estimated that 70 percent of that reduction was due to coaching, the program benefit was calculated at $35,000. The estimated returns were divided by coaching costs to calculate a return on investment.

Plan Evaluation in Stages

Evaluations can be resource-intensive. Therefore, set evaluation goals that are realistic in light of your resources. If you are just getting started with scenario-based e-learning, you will learn from your early efforts and improve your product. I suggest that initially you gather data most helpful to revising and evolving your early drafts and postpone evaluations that measure longer term effects. Specifically, before rolling out a new scenario-based e-learning lesson, start with a couple of pilot tests that include a small group of experts and representative learners to cull out glaring technical, content, or instructional errors or omissions not previously spotted. Use a second pilot with a larger group of representative learners to assess average times to complete the program, student satisfaction ratings, and learning outcomes.

Note that, by the time of the second pilot, to evaluate learning, you will need to have a valid test in hand. Therefore, you will need a test development process completed by the time the training is ready for pilot testing. Based on lessons learned from these pilots, revise your scenario-based e-learning. For example, if the testing data shows gaps in specific knowledge or skills, add or revise scenarios or scenario elements to shore up the training. After piloting, as you scale up the program, collect the type of data you used for the pilots and, if your client is interested, add indicators of transfer and return on investment such as bottom-line operational metrics.

Unfortunately, evaluations beyond student satisfaction are relatively scarce in workforce learning settings. As I will discuss below, test design and development is a labor-intensive process in itself, and many organizations either lack the resources or have concerns about potential legal consequences of employee testing. Therefore, the learning value of the bulk of training products more often than not is unknown. Still, I believe that it is better not to test at all than to attempt to measure learning with poor quality tests.

In the remainder of this chapter I will primarily focus on measures of learning effectiveness and use as examples tests from research studies that have either compared learning from various forms of scenario-based e-learning or have compared scenario-based e-learning with other instructional designs.

BACK TO THE BASICS: TEST RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY

To measure learning you will use some form of test. Even if you do not plan to evaluate individual learner achievement, a test is the best objective tool to assess the instructional effectiveness of your program. Because scenario-based e-learning often focuses on building problem-solving skills, you will need to construct tests that evaluate those skills. Nevertheless, the fundamentals of test reliability and validity still apply, and I would be remiss not to mention them. If a test is not valid, it does not tell you anything useful—in fact, depending on how the results are used, it might be very misleading. Additionally, a test is not valid if it is not reliable. In Appendix C, I review the basics of reliability and validity. I want to stress review! If you plan to construct tests, it’s always a good idea to consult with your legal department as well as engage the services of a testing expert—a professional called a psychometrician. For detailed information, I recommend Criterion-Referenced Test Development by Shrock and Coscarelli (2007).

TEST ITEMS FOR SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING

Many organizations either do not test at all or, if they do test, they may not have validated their test items. Therefore, I decided to draw upon published experimental research studies to identify the types of tests research teams used to assess learning effectiveness of scenario-based e-learning. In Chapter 10, I summarize a number of research studies that compared the instructional effectiveness of various forms of guided discovery learning (including scenario-based e-learning)—often to traditional training programs. To measure learning effectiveness in these experiments, the research team must develop and validate their tests. In reviewing the research studies, I noticed that most experiments used two or three different types of test items to assess both knowledge and problem-solving skills. In Table 9.2, I list six types of test items representative of the tests used in various experiments and include an example of each type.

TABLE 9.2. Sample Test Items to Measure Scenario-Based e-Learning Outcomes

| Outcome | Item Type Description | Test Item Example |

| Factual and Conceptual Knowledge | Items to assess understanding of concepts and application of facts associated with lesson tasks. Typically presented in multiple-choice format. | From a lesson for medical practitioners: Which of the following substances are typically excreted at an increased rate due to pheochromycytoma? Hydroxyl indolic acid and hydroxyproline Hydroxyl indolic acid and catecholamines Catecholamines and metanephrine |

| Strategic or Principle Knowledge | Items to assess deeper understanding of principles relevant to the learning objectives. Typically presented in multiple-choice or open-ended format. | From a lesson on electronics: You wire a subwoofer speaker with a resistance R = 16 Ω and a regular speaker with a resistance of R = 8 Ω in parallel and operate this circuit with a V = 6 V battery. What is the total resistance of this circuit? Draw a diagram for the electrical circuit described in this problem. |

| Near Transfer Procedural Tasks | Items to assess the ability to solve well-structured problems with correct or incorrect answers that are similar to the problems used in the training. Sometimes can be assessed by multiple choice, but may require a performance test. | From a class on setting up a grade book spreadsheet: Use the student names and scores entered in the attached spreadsheet to set up a grade book that will calculate a semester score in which unit tests are weighted four times more than weekly quiz scores. Review your calculation results to answer: 1. Anna’s semester score is: 68% 73% 75% 78% |

| Far Transfer Procedural Tasks | Items to assess the ability to solve well-structured problems with correct or incorrect answers that are different from the problems used in the training. Sometimes can be assessed by multiple choice, but may require a performance test. | From a class on setting up a grade book spreadsheet: Use sales agents’ names and weekly sales data entered into the spreadsheet to determine monthly commissions and total salary. Review your calculations to answer: 1. Mark’s take home pay for May, including commission, is: $2,357 $2,590 $3,029 $3,126 |

| Near Transfer Open Tasks | Items to assess the ability to solve a problem or demonstrate a skill for which there are multiple acceptable solutions. The test problem is similar to those practiced in training. | From pharmaceutical sales training: Review the account notes on Dr. Mendez and respond to her questions about Lestatin in a role play. |

| Far Transfer Open Tasks | Items to assess the ability to solve a problem or demonstrate a skill for which there are multiple acceptable solutions. The test problem is different from those practiced in training. | From pharmaceutical sales training: Drs. Oman and Smith want a consistent approach in their family practice that includes three nurse practitioners. Review their practice patient profile summary and role play a staff meeting in which you discuss a general treatment plan for obesity that includes Lestatin. |

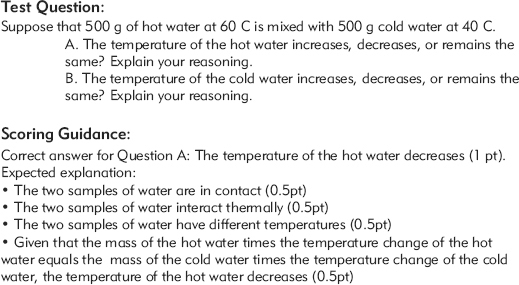

As I mentioned previously, open-ended responses require human evaluation. To keep the evaluation consistent, provide raters with a checklist and/or suggested answers that assign points to various response elements. (See the Inter-Rater Reliability discussion in Appendix C.) For example, in Figure 9.2, I show a sample test question from lessons on heat transfer taken from an experiment that compared learning from physical hands-on labs to learning from virtual labs. Note that the test includes a multiple-choice question but also asks learners to explain their reasoning. The explanations were reviewed by rater teams. To boost rater consistency, the answer key includes statements to look for in the explanations, along with points to assign to those statements. By the way, the research team found conceptual learning was equivalent in a virtual lab to conceptual learning in a hands-on lab.

DID I PASS THE TEST?

In experimental research, the goal is to compare the effectiveness or efficiency of one lesson version with a second version. For example, two scenario-based e-learning lessons are identical except one presents the scenario in text and the other presents the scenario with video. Upon completion, all learners take a validated test with items similar to those I described previously. The research team then compares the scores and runs statistical tests to determine whether one set of outcomes is significantly different from the other and whether the difference is of practical relevance.

However, in an educational or training setting, tests are used to determine (1) the effectiveness of the instructional material and (2) whether a given learner is competent to perform on the job. Therefore, unlike experimental studies, you will often need to determine a criterion for “passing” the test. Basically, a criterion is a “cutoff” score that distinguishes competent performers from individuals who lack the minimal knowledge and skills to perform effectively on the job. I often see an automatic 80 percent cutoff score assigned to tests. However, what does 80 percent mean? Is it acceptable to perform 80 percent of the key maneuvers while landing an airplane or performing surgery?

Cutoff scores can be important in situations in which learners are not allowed to do the job, blocked from promotion, not certified, etc., on the basis of a test score. Likewise, if you use the test as one metric of the effectiveness of your instruction, again the cutoff score will be important. Setting cutoff scores is a topic that exceeds the scope of this chapter. I will give some general guidelines and recommend that you consult your legal and psychometric resources.

First, all aspects of testing, including setting a passing criterion, involve judgment and you need to include input from stakeholders as you make this decision. Use a team to include job experts and management for guidance on cutoff scores.

Second, not all test items need be equal. Some items may be critical and must be performed at 100 percent proficiency. Others may be less critical and a lower cutoff score can be acceptable. For example, on a driver’s performance test, I would hope that certain safety-critical maneuvers must be performed at 100 percent accuracy. Others, such as parallel parking, may carry less weight. I know when I took my driver’s test, my parking score had to be quite low, but I passed based on such critical skills as forward and backward steering, stopping at stop signs, signaling turns, and so forth.

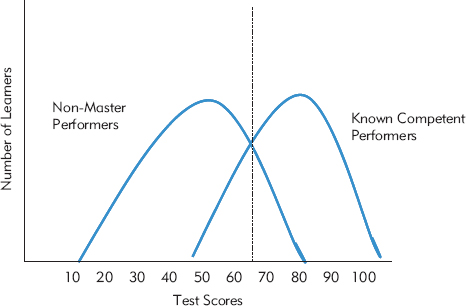

Third, you need to collect data to set a cutoff score and then review that data with your advisory team. Once you have built a test that is reliable and valid, per our previous discussion, you can give it to two different groups of individuals: fifteen workers who are known to be competent performers and fifteen workers who are non-masters. Don’t use just anyone for your non-master group. Instead, select individuals who have relevant baseline skills—the type of individuals who would be taking the training. Plot the scores of each group and set the cutoff score in the vicinity of the intersection between the groups. Take a look at Figure 9.3. In this example, the intersection of scores was 65 percent. Note that a few known competent performers scored below that number and a few non-masters scored above. Should you set the cutoff score at 70 percent and thereby fail a few who are actually competent? Or should you set the cutoff score at 60 percent and thereby pass a few who are not competent? Here is where your advisory team can help. If the skills are critical, a higher cutoff score is appropriate. For less critical skills and perhaps a need for more workers assigned to a given task, a lower cutoff score might be chosen.

FIGURE 9.3. A Distribution of Competent and Non-Master Performer Scores on a Test.

Fourth, remember that you need legal and psychometric consultation on any high-stakes test—tests that if not reliable, not valid, or defined with arbitrary cutoff scores could affect safety or other critical outcomes. Likewise, tests that are used for high-stakes personnel decisions such as hiring, promotions, and so forth should be carefully designed and developed. As you can see even from my brief summary, testing is a resource-intensive process in itself. Yet there really is no other valid path to objectively evaluating the instructional value of your scenario-based e-learning.

As I mentioned at the start of this chapter, for some organizations and contexts, tests may not be wanted or needed. In some cases, the learner’s satisfaction, as indicated by rating sheets, focus groups, social media reviews as well as enrollment and completion statistics, may be sufficient. In other situations such as the soldier suicide prevention program, bottom-line data may be enough to sell your approach. No two evaluation situations are the same, but by now you should have the basics to adapt an evaluation strategy to your situation and to identify qualified experts to guide your project.

TESTING WITH ONLINE SCENARIOS

In the previous sections I discussed traditional testing formats such as multiple choice and performance tests to assess the knowledge and skills learned from your scenario-based e-learning course. You could also use your scenario lesson interface as a testing tool. You would use a design similar to that described in this book, with the omission of guidance and learning resources other than the type of support that would be available in the normal work environment such as a reference resource. You would present scenarios not used in the instructional phases. Your scenarios could be structurally similar to those presented in the training to measure near-transfer learning as well as structurally different if you want to assess to what extent learners can adapt what they learned to different situations. For example, in a class on preparing a grade book with Excel, a near-transfer question would provide a different set of student data and ask learners to set up a grade book. A far-transfer question would provide data and ask learners to use Excel to set up a budget.

One of the challenges of testing with scenarios is scoring. If your scenarios are highly structured with correct and incorrect answers, you can set up a relatively traditional automated scoring and passing scheme applying standard testing methodologies for reliability and validity. For the automotive troubleshooting example used in this book (see Figures 1.1, 1.2, and 6.5), the client assigned a score for identifying a correct failure on the first attempt and also assigned points for the actual elapsed time to complete the scenario as well as the virtual time needed to complete the repair. The time data serves as a useful proxy measure for application of an optimal troubleshooting sequence. In contrast, if your scenarios are ill-structured, with multiple acceptable answers such as a role play, you may need human graders using a rubric to evaluate them.

In a blended testing approach, you could use traditional multiple-choice items to evaluate knowledge of facts and concepts, followed by scenario-based items to assess application of mental models, heuristics, or principles to job-relevant situations. If you need to evaluate hands-on procedures with shop equipment, for example, you will need a hands-on performance test. By defining the different knowledge and skills needed for a given level of competency, you may be able to automate part of the test and use human graders to assess just the important elements with high response variability.

If your professional domain has developed a validated certification test using traditional testing formats, you might be able to automate parts of it as a scenario-based test. For example, if an automotive technician is traditionally tested and scored in a hands-on shop environment, you could adapt the scoring and passing standards to a scenario-based test. The online scenario-based test could measure the troubleshooting problem-solving process but not procedural skills of manipulating equipment. If you need to evaluate both problem-solving and procedural skills, a blended testing approach might be best. If your domain does not have a validated certification test, you may need to validate and set passing scores yourself using the methodologies summarized previously in this chapter.

Because using a scenario-based environment for assessment of ill-structured problems is a relatively new approach, I recommend you consult with a measurement specialist for guidance.

WHAT DO YOU THINK? REVISITED

Now that you have read the chapter, you may want to revisit the questions below to consider whether they are true or false.

In my opinion, all of the statements are false, except Number 3. In some cases you can use a multiple-choice test to measure the knowledge topics targeted by your objectives as well as some skills that, when applied, result in clear-cut right-or-wrong answers. For example, you can provide a scenario and ask a series of multiple-choice questions about it. However, in many cases, scenario-based e-learning focuses on more ill-defined outcomes that require an open-ended response.

Regarding Number 1, there is good evidence that there is little relationship between how participants rate their class and their actual achievement as measured by a test (Sitzmann, Brown, Casper, Ely, & Zimmerman, 2008). You will need a reliable and valid test to assess the learning effectiveness of your scenario-based e-learning. Therefore, I consider this statement false.

For Number 2, in many cases it is difficult to show a bottom-line dollar gain from any training program. Therefore, I rate Number 2 as false. You may have the opportunity when outcome goals such as sales or suicide prevention are closely linked to bottom-line metrics that are routinely reported and you can show a difference in those metrics either before and after training or between a group that receives training and a group that does not. However, many factors will affect bottom-line measures, so it’s often not practical to draw firm conclusions from these types of comparisons.

Regarding Number 4, I believe that there is nothing so unique about scenario-based e-learning that exempts it from being evaluated for its learning effectiveness. Just as with any training program, your design should include learning objectives that are measurable. I mark this statement as false.

Number 5 is another false statement. Too often “passing” scores are set arbitrarily, rather than based on data—both objective and subjective. Previously in the chapter, I introduced a couple of techniques for you to consider if you need to set passing scores for certification purposes.

COMING NEXT

In addition to (or in lieu of) conducting your own evaluation, I recommend that you review the research evidence on scenario-based e-learning. Because the approach is relatively new, the research base is somewhat limited—but growing. Some research compares learning outcomes from guided-discovery designs to outcomes from other designs. Other experiments aim to define which features of guided discovery optimize learning by comparing different versions of a guided-discovery lesson. In Chapter 10 I will summarize recent research on these questions.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Phillips, J.J. (2007). Measuring the ROI of a coaching intervention, part 2. Performance Improvement, 46, 10–23.

A great practical article on measurement of ROI of management skills—often considered very hard to measure.

Schraw, G., & Robinson, D.R. (Eds.). (2011). Assessment of higher order thinking skills. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

A rather technical book with chapters from various scholars. Recommended for anyone interested in a more advanced/detailed set of perspectives on this important topic.

Shrock, S.A., & Coscarelli, W.C. (2007). Criterion-referenced test development (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

The Shrock and Coscarelli book has always been my guide when it comes to any form of test development, and they have kept their classic book updated. Should be on every trainer’s shelf.

- Do learners like scenario-based e-learning?

- Does your scenario-based e-learning lead to effective learning?

- Is your scenario-based e-learning efficient?

- Does your scenario-based e-learning lead to improved work performance?

- Does your scenario-based e-learning give a return on investment?

- Other evaluation questions you or your stakeholders might have: