CHAPTER 12

IMPLEMENTING SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING

In previous chapters we’ve reviewed the analysis, design, development, and evaluation of scenario-based e-learning. But I would be remiss not to acknowledge the importance of the context in which your scenario-based e-learning courses are proposed, approved, created, and deployed. You can adopt a low- or a high-profile road to your project. A low-profile approach involves planning, creating, and deploying a scenario-based e-learning lesson or course with a minimum of fanfare, typically using your tried-and-true processes for e-learning projects. You may even decide not to give any special name or attention to the project. A low-profile approach is the “better to ask forgiveness than to ask for permission” path. It might be the wiser path to design and test your first projects, buying you time to learn and improve subsequent efforts.

However, if you are planning a scenario-based e-learning course that will consume more resources than normal or will otherwise draw attention, or if it is a course that you would like to use as a showcase piece for your organization, it’s a good idea to do some high-profile prework to obtain and maintain stakeholder support. In this chapter I summarize four steps to a successful project—steps that you can implement informally and quietly with a small team or that you can deploy in a formal and visible project process.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

As prework for you, put a checkmark next to statements that you believe or have found to be true in your training projects:

FOUR STEPS TO PROJECT SUCCESS

Let’s take a look at some steps you can adapt to your own context that will increase the probability of getting your scenario-based e-learning off the ground and minimize the turbulence of a new design and development effort.

STEP ONE: PRESENT A STRONG BUSINESS CASE

In many situations, you will need to “sell” your scenario-based e-learning project—especially if it will require substantial resources or will be uniquely visible to your client as an approach quite different from status quo courseware. In the following sections I provide suggestions, along with some sample resource data based on recommendations from experienced scenario-based e-learning practitioners.

Visualize Scenario-Based e-Learning for Stakeholders

Chances are your stakeholders won’t know what you mean by scenario-based e-learning or whatever term you decide to use. I recommend that you start your kickoff meeting with a demonstration. It could be a rough prototype of the course you are planning or some samples of external courses that effectively illustrate the key design features of scenario-based e-learning. When selling scenario-based e-learning, a few pictures really are worth a thousand words. Starting the conversation with an effective, concrete example gets attention and generates immediate interest. Depending on your audience, you may even want to contrast scenario-based e-learning with a more traditional directive or receptive lesson to stimulate a discussion of the differences between them.

Determine the Magnitude of the Performance Gap

I assume that you have completed a performance analysis and determined that a knowledge and skill gap is one barrier to achieving organizational goals. At this point, get an estimate of the costs of the skill gap. The costs of ineffective performance can help you position the potential gains from an investment in scenario-based e-learning. Take your first clues from a review of performance data linked to operational goals such as sales, customer complaints, scrap, audits, fines, and so forth, supplemented by staff interviews and observations at field sites. Some typical comments or data from management might allude to dollars lost due to waste, lost sales, employee attrition, or customer dissatisfaction. Ask questions such as: “In an ideal world, if everyone is performing close to the level of our most productive workers, what percentage improvement or dollar gain is it reasonable to expect?”

During the performance analysis, identify the workers, worker teams, job roles, and tasks that most contribute to the organizational goals, along with the specific knowledge and skills that distinguish high from low performers. Document the main knowledge and skills, such as those listed in Table 2.1, as well as the predominant scenario learning domains listed in Table 2.2. For example, suppose that data and management interviews point to electrical troubleshooting as a major task category leading to performance gaps, such as disappointed customers or too much time wasted in inefficient problem solving. Close observations may show that more proficient performers follow a logical troubleshooting process, review schematics early in the problem-solving stages, and also draw on a mental bank of heuristics related to electrical troubleshooting. Your analysis suggests that building expertise around electrical troubleshooting will reduce the performance gap.

Incident-Driven Training

In some situations your training may be driven by an incident or problem that was sufficiently costly to mandate training as a remediation. In these cases, join the investigation team (or form your own team) to identify the reasons for the incident, and stress to anyone who will listen that training alone is rarely the solution to problems of this type. Often stakeholders will mandate training as a fix-all solution to an incident and assume the problem is now resolved, neglecting other critical performance factors, such as work standards, feedback, and incentives, for example. In other words, take a broad performance perspective. At the same time, no doubt training will be one of the solutions. To mine maximum value for the training effort, conduct interviews about the incident from those involved as well as from other experts to identify the core knowledge and skill gaps, as well as to identify the most relevant scenario domains.

Compliance Training

Compliance training is often a mandated event required by internal or external regulatory bodies. The training is organized by compliance topic or content, such as information security, ethical conduct, or workplace discrimination. Some lessons simply present the principles—often in terminology written by legal staff. Others include some examples and non-examples and may even add a few interactions. The workforce typically dreads the annual compliance ritual and invests minimal mental effort. The learning management system (LMS) tracks “completions” of these courses, and the “training requirement” box has been checked.

Unfortunately, topic-centered lessons on compliance regulations have a small chance of being translated into work behaviors that will minimize the adverse effects of violations. If any of the previous description sounds familiar, it might be time to treat compliance like any other important knowledge and skill topic and integrate it into task-centered training, performance support, and other critical performance factors, such as specific goals, regular and specific feedback, incentives, reminders, and so on. This does not necessarily mean you need to use a scenario-based e-learning design, although it does offer a solution to make compliance training interactive and job-centered.

Identify Tradeoffs to Diverse Solution Options

Consider the different ways that your training has been or could be delivered to achieve the performance goals. For example, to build automotive troubleshooting expertise, training could be delivered via (1) on-the-job training (OJT) using coaching during actual shop operations, (2) instructor-led classes using either real or mocked equipment with simulated failures, or (3) a scenario-based e-learning self-paced lab similar to the one I have shown in this book.

There are several drawbacks to an OJT approach. First, in an actual shop, auto failures will not present themselves in a balanced or optimal sequence for learning. Second, the learning environment will be inconsistent, depending on the coach and the particular failures that surface. Third, each shop will have to allocate the time of an experienced worker for coaching purposes. Last, learning time will be equivalent to real elapsed time needed to resolve a failure. On the positive side, no additional time is needed to develop instructional materials, so actual work can be accomplished during the training cycle.

A well-planned instructor-led lab using real equipment with actual or simulated failures has the advantage of consistency and a logical learning progression. Likewise, it makes efficient use of expertise by assigning one or two expert instructors to a group of learners. In addition, the high social presence among instructors and students in a classroom or laboratory setting can add instructional value. On the downside, learners will incur travel costs getting to and residing near centralized training centers. Secondly, although time to perform repairs will be more efficient than in an OJT setting, it will still be longer than in a simulated multimedia environment.

In contrast, if using a scenario-based e-learning self-paced lab, similar to the instructor-led class, the sequence of failures can be organized to provide a consistent and optimal learning experience. Also, with the scenario-based e-learning, you will accrue savings in travel expenses and learning time will be compressed. Depending on the size of your current and anticipated learning audience, these savings could be considerable. On the downside, a scenario-based e-learning development project may require a larger up-front investment than a face-to-face class and may also cost more to update, depending on (1) what media you use, for example, video versus animation, as well as (2) the volatility of your content. Therefore, you will need to estimate costs incurred and saved to present a balanced argument.

As you can see, each delivery option has advantages and disadvantages. This is the reason that a recent U.S. Department of Education Report (2010) found best learning from blended solutions that made use of the best features of a combination of in-person and digital training. For example, novice technicians could start training with a prework self-study program that oriented them to basic terminology and troubleshooting methods. Next, a two- or three-week instructor-led session would consist primarily of hands-on troubleshooting in a laboratory setting. Third, after some time back on the job, scenario-based e-learning could be used to accelerate expertise of apprentice technicians.

Delivery Media Tradeoff Analysis for Automotive Troubleshooting

Automotive service industry experts estimate that a typical entry-level technician may require exposure to about one hundred successful diagnostic experiences (that is, one hundred work orders) in order to achieve baseline troubleshooting competencies in a particular class of failures such as brakes, transmission, engine, etc. In Table 12.1 I summarize the amount of time needed to complete the one hundred work orders in the three delivery environments summarized above. As you can see, the scenario-based e-learning requires only about 16 percent of the training time needed in an OJT environment to achieve minimal competency. You will need to translate that time savings into dollars to determine whether the savings justify the expense to design and develop scenarios.

TABLE 12.1. Time to Reach Automotive Troubleshooting Competency in Three Learning Environments

| Learning Environment | Time/Work Order | Time to Complete 100 Work Orders |

| In Dealership: OJT | 2 to 6 hours | 200+ hours |

| Instructor-Led | 1 hour | 100 hours |

| Scenario-Based e-Learning | 20 to 40 minutes | 33 to 66 hours |

To apply this process to your own context, list your delivery alternatives with advantages and disadvantages to each. Determine the number of current and future projected learners. Evaluate the volatility of your content. Ask experienced supervisors or managers for estimates of the approximate number of situations or cases needed to achieve target levels of competency, and contrast the time and other costs to achieve those levels. See Table 12.2 for a checklist summary.

TABLE 12.2. Steps to Compare Training Delivery Alternatives

Highlight Opportunities to Build Expertise That Are Unavailable or Impractical in Workplace

In many settings on-the-job training may simply not be an option because skills cannot be practiced in an operational setting. Tasks with safety consequences, such as leading a combat mission or making anesthesia decisions, offer two examples. Even if OJT is possible, learning on the job may lead to customer dissatisfaction—or simply may take too long. For example, a long-term sales engagement may require weeks or months to play out, whereas in a virtual world that time can be compressed. In Chapter 2 I summarized a number of tasks that are not feasible to practice in an actual work setting and thus are good candidates for scenario-based e-learning.

Leverage the Motivational Potential of Scenario-Based e-Learning

Because the trigger event of a scenario-based e-learning lesson situates the learner as an actor to resolve a work-related problem, learning can be both highly engaging and immediately relevant. Research evidence and anecdotal comments suggest that, compared to traditional approaches to learning such as lectures, scenario-based e-learning is more popular with students. Particularly for content that is potentially boring—compliance courses filled with policies and legal mandates, for example—a scenario-based e-learning approach may lead to higher ratings as well as deeper mental engagement that translates into desired behavioral changes. Consider building a short prototype lesson in PowerPoint and testing it out with a small group from your target audience to confirm that the design will be positively received.

Present Evidence on the Benefits of Scenario-Based e-Learning

In Chapter 10 I summarized research evidence that compared learning from scenario-based e-learning to learning from alternative lesson designs or that compared learning from different versions of scenario-based e-learning. Although limited, we do have evidence that a scenario-based e-learning design can generate more effective transfer of learning than other designs and can accelerate expertise through compressed experience. If your stakeholders are likely to be interested in evidence, show some of the research findings I summarized in Chapter 10.

Estimate Your Production Costs

No doubt some of your stakeholders will be impressed by your demonstrations and discussions of acceleration of expertise with scenario-based e-learning. Still they will ask: “That’s all well and good—but how much is this going to cost?” I recommend you incorporate not only the potential cost savings but also production costs as part of your presentation.

As an experienced e-learning developer, you might have data from your previous projects in the form of costs to produce an hour of multimedia learning. Typical estimates range from seventy-five to two hundred hours of analysis, design, and development time per hour of instruction for a receptive or a directive approach to software training. Analysis, design, and production times and resources are often higher for scenario-based e-learning—especially for initial scenarios. Some major factors that will determine your scenario-based e-learning costs include (1) complexity of your design, (2) the navigational structure you plan to use, (3) the media you might include, such as video, audio, computer animations, or still visuals, (4) what, if any, cognitive task analysis is needed, (5) the extent to which you can reuse lesson templates for multiple scenarios, and (6) what expertise and authoring resources you will need for design and development.

In Table 12.3 I summarize the time and costs estimates for three different scenario-based e-learning treatments for a troubleshooting lesson: branched, menu-driven, and whole-screen active object. The resources are estimated as total hours per simulation and costs per scenario. I was surprised to see that the branching template was the most time-consuming, not only for the first scenario but also for subsequent scenarios. In contrast, the whole-screen design required four to five hundred hours for the first simulation; but with the basic graphics, programming, and design completed, subsequent simulations were much less expensive. Once the simulations for the on-screen objects were programmed in Flash, the data was imported to XML making it easy to repurpose to new scenario problems.

TABLE 12.3. Hours and Cost Comparisons for One Troubleshooting Scenario for Menu, Branched, and Whole-Screen Designs

Keep in mind that this data is based on scenarios that are relatively complex, requiring access to multiple sources of case data and tracking of the learner’s choices during solution. Other domains that require less case data will show different cost patterns. An important point is to consider not only the cost of the initial scenario but how those costs might differ for subsequent scenarios.

STEP TWO: PLAN YOUR PROJECT

Having gained approval for a scenario-based e-learning course, consider the time and resources needed for the major analysis, design, development, and evaluation activities.

Plan and Secure Your Resources

As you scope out your project, identify the critical resources you will need, including SME time, graphics, instructional design, and programming expertise. If you are new to scenario-based e-learning and plan a project of medium to high complexity, I recommend you work with an experienced development firm for your initial project. More often than not, the investment in their expertise pays off in fewer pitfalls, sidesteps, and outright project failures. With or without consultant support, you will need SME time. If you are targeting critical thinking skills and will need cognitive task analysis to elicit tacit knowledge, that time could be considerable. Don’t forget to also specify the quality of the SME’s expertise. Some managers will make their less proficient SMEs available because they can most afford to lose their input to ongoing projects.

Over-estimate your needed SME resources (time and quality) and negotiate those resources with your stakeholders before you commit to the project. Inappropriate or insufficient SME availability is a common cause of projects that either fail or fall far short of potential. Remember the critical elements of your course, such as what scenarios to use, what distinguishes an easier from a more challenging scenario, the work flow, the sources and interpretation of case data, the rationale and heuristics for problem solution, the feedback—all ultimately come from your SMEs. Better to pass up on a scenario-based e-learning approach than to proceed with suboptimal SME input.

Define and Classify the Target Knowledge and Skills

Depending on the scope of your project, defining and classifying the knowledge and skills to be incorporated into your scenarios may well consume a major segment of overall project time. But it’s time well spent. Although the outcomes may be readily specified, breaking these into classes of specific behaviors with associated knowledge and arranging those classes in an optimal sequence of scenarios for learning is a major design task. In Chapter 11, I summarized some techniques you can use to elicit tacit knowledge from experts and to identify what features distinguish simpler from more complex tasks.

As you identify the outcomes and associated knowledge, define domains and tasks within those domains. In domains that involve a problem-solving process—domains such as diagnosis and repair, research, or design—document the work flow of an expert performer. For example, in automotive troubleshooting of an electronic failure, the expert follows six steps to isolate and repair the problem. For domains that require application of policies and procedures, identify the correct policies for each scenario class. For tradeoff domains, identify main sources of diverse expertise and find ways to embed virtual advice into your program.

As you identify the main tasks associated with the work flows or policies, translate them into learning objectives. For example, the automotive troubleshooting course would fall primarily into the diagnostic domain, and critical tasks might include troubleshooting of electronic failures, hydraulic failures, and mechanical failures. A sample learning objective is: “Given a work order with XXX symptoms, the learner will select and interpret appropriate tests and identify the correct failure in the most efficient manner.” Recall from Chapter 4 that your design will require a translation of these high-level objectives into more detailed statements that specify the behaviors learners can perform online to record the actions and decisions they make during scenario resolution. For example, the general troubleshooting learning objective may be translated to: “Given a work order specifying XZY, the learner will click on an optimal sequence of on-screen tests and select the correct failure from a list of fifteen failures.”

Consider Your Evaluation Strategy and Secure Resources

Yes, I know it’s early in the project and you are busy getting it off the ground. However, an effective evaluation requires planning from the start of your project. Do you need to measure both learner satisfaction and learning? Will you have to develop reliable and valid tests to assess learning? Will you have to conduct a formal validation of any tests used for certification purposes? Is there an opportunity to measure transfer to the job and/or bottom-line benefits of your course? All of these tasks require time and resources that are best factored into the original project plan.

STEP THREE: DESIGN YOUR APPROACH

Template Your Scenario to Align to the Workflow or Design Model

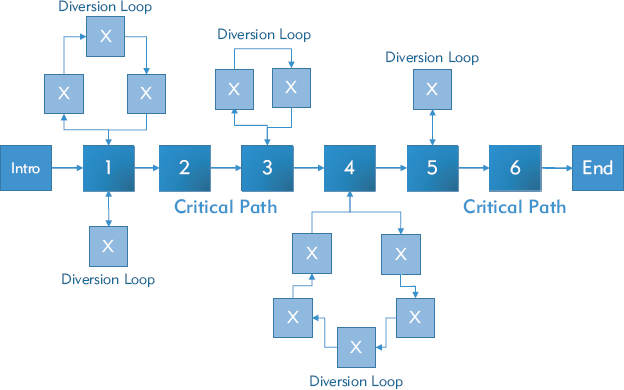

Take a look at Figures 12.1, 12.2, and 12.3 to review models of templates for the whole-screen, menu, and branched scenario designs. Note that for the automotive troubleshooting lesson using the whole-screen design (Figure 12.1), five core screens serve as the basic template for all scenarios. For a branched scenario template, first map out the critical path, that is, the series of choices that lead to the specified outcome, and then add diversion loops along different stages of the path. Base diversion loops on plausible misconceptions that could lead to suboptimal choices. If using a menu navigation, menu options could reflect the main stages of the workflow or they could be structured to lead to the main design components, such as case data, guidance and instructional resources, outcome deliverables, and so forth. You can contrast the menu structure for the bank underwriter lesson (Figure 5.1) with that for Bridezilla (Figure 6.6). The bank menu tabs primarily reflect the workflow, whereas the Bridezilla menu tabs primarily link to guidance and instructional elements.

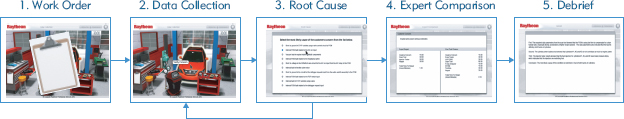

FIGURE 12.1. A Sample Template for Whole-Screen Automotive Troubleshooting.

With permission from Raytheon Professional Services.

FIGURE 12.2. A Sample Template for Menu Design of Automotive Troubleshooting.

With permission from Raytheon Professional Services.

FIGURE 12.3. A Sample Template for Branched Scenario Design of Automotive Troubleshooting.

With permission from Raytheon Professional Services.

Whatever design approach you select, thinking in terms of a template will save you time and resources in later lessons.

STEP FOUR: DEVELOP YOUR FIRST SCENARIO

Many books have been written on e-learning development, so I will not replicate their guidance here. However I do recommend a couple of steps especially relevant to scenario-based e-learning

Build and Test a Prototype Lesson

I mentioned previously that as part of your business case, you show your stakeholders either an actual lesson from outside your organization or a prototype you have built. However, as you complete the design activities, you now have a much clearer idea of the content and the learning objectives and have made some decisions about the screen layouts and navigation. You may routinely build prototypes as part of your e-learning development process. If not, it’s a good idea to develop a simple operational prototype of your first scenario. Test the prototype with a few SMEs not involved in the design to glean technical input, and also test with a few learners typical of the target audience to identify problems such as missing content or lack of guidance. If you have developed a learning test, use it now to identify gaps in the instructional support in your lesson.

Build a Lesson Orientation

If your organization and staff are new to scenario-based e-learning, I strongly recommend a student orientation. Learners used to listening to online lectures or working within the structure of a directive learning design risk disorientation by a learning goal that puts them at the center of the action. Some may feel lost or confused. I recommend you prepare a succinct but meaningful introduction that explains the rationale expectations and main features of the course. Figure 12.4 shows an example from the Bridezilla course.

FIGURE 12.4. Part of the Introduction to the Bridezilla Course.

Plan Course Launch

We all know that, just because we build it, they won’t necessarily come. Or if they have to come, they may not really be there. Apple Computer devotes a great deal of time, attention, and energy to new product advertising, packaging, and announcements. How effectively has your team deployed new e-learning products in the past? Were multiple channels used to announce the courses or did they simply show up one day as a new link in your LMS? Was social media used to announce, review, and rate the courseware? If your previous implementations have been suboptimal, use the scenario-based e-learning course as an excuse to plan a better rollout strategy.

Document “Lessons Learned”

No project flows as we first anticipate. The end product is likely different from your initial vision. Unanticipated outcomes—both negative and positive—emerge along your path. To maximize value from your first efforts, elicit and document lessons learned. Collect data from a variety of sources, including a project manager’s journal, input from SMEs, your design and development team, managers, and learners, formal data collected from evaluation tools, spreadsheets, and so forth. Synthesize your data into a report that can inform your next projects to promote a cycle of continuous improvement.

WHAT DO YOU THINK? REVISITED

We started the chapter with some statements for you to consider, based on your previous experiments or instincts. Below are my opinions.

Although there are always exceptions, I believe the first three statements are generally true. Especially if your scenario-based training project is a relatively new approach or will involve different processes and/or more funding than your previous projects, I recommend careful analysis, project planning, and communication with your stakeholders and design/development team. I think a prototype lesson goes a long way to advance your project by helping stakeholders, subject-matter experts, and staff understand the approach and also to pinpoint missing requirements early in the process.

Regarding D, I believe that scenario-based e-learning has some potential opportunities for good ROI, but certainly not in all situations. I recommend it be used as one resource in your toolkit of performance solutions used to help your organization achieve bottom-line objectives.

COMING NEXT: YOUR SCENARIO-BASED e-LEARNING PROJECT

This chapter concludes this book, which I hope has given you a useful overview and solid introduction to the major features and applications of scenario-based e-learning. Like all learning approaches, scenario-based e-learning is not suitable for every performance gap and every training need. My hope is that the guidelines and examples in this book will help you pinpoint optimal opportunities and adapt these ideas to your own organizational needs. It’s always helpful to hear from you with suggestions, success stories, and lessons learned. Please contact me at [email protected].

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Cross, J., & Dublin, L. (2002). Implementing e-learning. Alexandria, VA: ASTD Press.

Phillips, J.J., & Phillips, P.P. (2007). The value of learning: How organizations capture value and ROI and translate it into support, improvement, and funds. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

There are many excellent resources on training implementation. I recommend you supplement this list with a search using terms such as implementing training, implementing e-learning, training project management, and so on to find resources related to the topics of this chapter.

- What is scenario-based e-learning: Start with demonstrations.

- What are the current costs of the organization’s performance gaps?

- What is the tradeoff costs among alternative delivery approaches?

- How can the advantages of different delivery options be optimized in a blended solution?

- How much time could be saved with acceleration of expertise?

- What is the feasibility of building expertise on the job (OJT)?

- What is the motivational potential among your learners of a scenario-based e-learning approach?

- What is the evidence of the effectiveness of scenario-based e-learning?

- What are the cost estimates for development of scenario-based e-learning?

- What is an estimate of the costs and benefits of a scenario-based e-learning approach along with a summary of the resources (don’t forget SME resources) you will need to design and produce an effective product?

- Other:

- Secure the resources you will need for the project.

- Define critical work tasks to be trained linked to the performance gap.

- Plan the evaluation.