1. The Nature of Trading

“You always need a catalyst to make big things happen.”

—Jim Rogers1

The market is losing $718 million per second. The clock is ticking. Millions—no, billions—down the drain. Your positions are getting eviscerated. Down, down, down. What should I do? What can I do? What is going on?

This is not a scenario out of a movie—it really happened during the Flash Crash of May 6, 2010. Considering the complexity of the modern market, it is a matter of when, not if, it will happen again.

In a market where high-frequency traders (HFTs) account for 84% of U.S. stock trading volume, how can you make money?2 In a world of uncertainty, how can you minimize risk and maximize profits?

What moves stock prices? What moves the overall stock market? How can you profit, given the catalysts precipitating sudden sharp changes in stock prices? This book answers these questions and more. It is filled with numerous real-life examples to illustrate both the potential profit opportunities and risks that market shocks induce. From the actions of corporate executives to the rulings of regulators, from earnings announcements to merger deals, from lawsuits to settlements, from macroeconomic reports to government policy actions, and from elections to terrorist actions, Shock Markets takes you inside the market to understand what happens and why. This includes analysis of the market during fads and fashions, bubbles and crashes, and market crises. It also explains how to create and implement a solid trading game plan.

Why Study Market Shocks?

Market shocks illuminate reactions in the market to news. Studying past market shocks is key to understanding and reacting to future market shocks. When the next shock happens, you likely will have only moments to react. Will you be ready?

The analysis of market shocks enables you to isolate the market’s reaction to a specific news event. Moreover, the analysis of the market reaction to a specific news event provides clues to the trading themes driving the market.

Financial markets can be tranquil or turbulent. Both are characterized by periodic shocks. Shocks create risks as well as profit opportunities. Extreme price moves are more common than you might expect. Numerous sources of shocks exist. How markets react to shocks contains important lessons for market participants. Many successful traders argue that they make most of their profits from only a handful of trades each year. Gradual profits (or losses) arise from riding a trend. However, quick profits (or losses) arise from sudden, sharp shocks to market prices. That’s why understanding market shocks is so important.

Individual stocks are more volatile than the market as a whole. What might constitute a market crash (down 20% or more), or a major rally, can occur in a single day for individual stocks. This means both risk (for those unprepared) and opportunity (for those who have prepared to take advantage of market shocks).

Market shocks can be small, or extraordinarily large. Take the example of Medbox, a company that creates medical marijuana dispensing machines. In mid-November 2012, after several voter referendums sought to legalize marijuana at the state level, it saw its share price rise 3,000%,3 surging from a market capitalization of $45 million to up to $2.3 billion.4 Although the stock surge from $4 to $215 was transitory, the price remained significantly elevated from $4, spending the month after the shock trading between $20 and $100.

Market shocks happen every day. Although this book includes some examples from the more distant past, the focus is on more recent examples for two reasons. First, the reactions to a given shock may change over time, so recent examples give traders a better idea of the likely market reaction than older examples. Second, recent examples are more likely to be both relevant to and more easily understood by today’s trader. The examples considered are by necessity illustrative rather than exhaustive.

In today’s globally connected world, shocks in one country can spill over and spread across the world. Capital flows easily and quickly around the world. Still, the U.S. represents 45% of world equity value and is a prime candidate for study.5 This book includes examples of shocks from around the world, although many of the examples involve U.S. traded firms.

The Nature of Trading

Trading is essentially a game. Like other games, it requires both skill and intelligence. Over the short run, luck plays a role in determining trading performance. However, over the long run, luck washes out and trading skill determines performance. What makes trading so challenging is that although the objective of the game is constant (to make money), the “rules” of the game may change over time as the reaction of other market participants to the same event may differ over time.

Active financial markets are dominated by traders and trading activity. Trading impacts the behavior of financial market (or speculative) prices. Understanding how traders make decisions is important for all market participants.

One important implication of having financial markets dominated by traders and trading activity should be kept in mind: Market prices can deviate from intrinsic value over significant periods of time. These deviations can create investment opportunities for value investors or long-term traders.

How does trading differ from investing? Trading and investing have many characteristics in common. Both involve the assumption of risk. Both are profit oriented. Although many trades are held for short periods of time, the trading horizon need not be shorter than the investment horizon. Nor do the two activities need differ in terms of what is traded or the risk assumed.

Trading differs from investing in the following way: Most investment decisions are based on how the market price of a security differs from its intrinsic value. Thus, the rule is to buy when the market price is less than the intrinsic value or sell when the market price exceeds the intrinsic value. This rule contains the implicit belief that the market price of a security will converge eventually to its intrinsic value.

In contrast, with the exception of arbitrage transactions, traders are not concerned with the relationship between price and intrinsic value per se. Rather, traders are concerned with the likely change in price over their trading horizon regardless of intrinsic value.

Different Perspectives of Trading

There are many ways of looking at trading. First and foremost, trading is about making money. How you get there is the important question. Trading is about understanding past, and predicting likely future changes in prices. Simply stated, trading is about forecasting.

Trading is also about taking calculated risks. Put differently, trading is about expectancy management—that is, understanding the probability of potential outcomes in a bet. With the exception of arbitrage transactions, all trading entails the assumption of risk. A trading firm expecting to win 51% of the time has an edge like a casino. It might lose on any given bet but should win as the number of transactions increases. The more transactions that are executed, the more assurance the firm has that it will make a profit. Such a firm will think in terms of the volume of transactions instead of the number of trades made over an arbitrary period.

Trading is also about managing risk exposure effectively through risk management: Proper risk management means being aware of all potential risks. This seems obvious but it is surprising how sometimes risks are not well understood even by professionals. Hedge fund managers strive to earn a superior return or alpha for a given level of risk. The financial crisis demonstrated that many hedge funds were not pursuing alpha strategies, where they earned a superior return for a given level of risk, but rather beta strategies, where the seemingly higher return was compensation for bearing risk rather than a source of superior return.

Trading is about decision making, usually under conditions of uncertainty. Traders need to utilize prior information as well as avoid potential decision pitfalls.

Trading is about finding and exploiting an edge or comparative advantage. Where is your trading edge?

Arguably, the most important feature to recognize about trading is that trading is a game. As a game, it is important to understand the strategies and anticipate the likely behavior of other players. Trading entails an element of strategy that depends on what other traders are doing and how other traders will react. Successful trading strategies need to be dynamic as situations change.

Trading is about understanding odds. Although traders would love to place bets where the only outcome is profitable, risk is invariably involved. The secret is not to look for even-money bets, but one-sided bets where potential payoffs are skewed in your favor.

There are a number of popular misconceptions about trading and traders. For example, no one can predict every price move in the marketplace. However, you don’t have to do so to be a successful trader. Most successful traders have more losing trades than winning trades.

What kind of batting average do you need to get into the major leagues in baseball? Many would argue that a batting average of 300 (that is, hitting the ball 30% of the time when at bat) would be enough to qualify. The quintessential discretionary trader, Paul Tudor Jones II, is a member of the Forbes 400—a list of the 400 wealthiest Americans. Yet, he once said that 70% of his trades were losers. How can he be one of the most successful traders if he loses the majority of the time? The answer is that he cuts his losses short and lets his profits run. He is batting 300.

A common misconception about trading is that traders love taking risk. To be sure, risk provides opportunities that traders seek to exploit. However, traders prefer to take less risk rather than more. The ideal trade is what George Soros called “uneven bets,” or trades with payoffs skewed in the desired direction. Some of the most famous trades have been those where the bets were uneven.

Although trite, successful trading entails buying low and selling high, although not necessarily in that order. This is true whether you are trading price or volatility. The rules governing trading are simple. Following them is hard.

The common perception of successful trading is that of a trader identifying and implementing a brilliant trade before a sudden change in price or volatility. For example, John Paulson made $13 billion for himself and his investors from shorting the subprime mortgage market before the financial crisis of 2007–2009. John Arnold became a billionaire after his firm was on the other side of the Amaranth trading debacle in 2006. George Soros is famous for “breaking the Bank of England” in September 1992 by betting that the pound sterling would fall. Paul Tudor Jones II is famous for anticipating and profiting from the stock market crash of October 1987. All of these traders made trading decisions on a discretionary basis by examining the fundamentals (and sometimes the technicals).

The identification of potential trades, the selection of the “best” trade among the set of potential trades, and trade execution are all important. Being right is important, but it is not the most important factor. Arguably, the most important factor for successful trading is risk control. The good news is that sound risk control techniques can be taught.

Most individuals have a bias toward trading stocks. They also have a bias toward trading on a discretionary basis and trading off of perceived economic fundamentals. Most individuals also have a bias toward being long—that is, buying a stock in the hope of selling it later at a higher price. You can make money in up markets or down markets. Restricting yourself to always being long also restricts your potential profitable trading opportunities.

Market Conditions and Sentiment

Market shocks can create or destroy fortunes within seconds, so how can traders profit and protect themselves from these waves in the market?

You don’t trade with yourself, so understanding how other market participants think about the market is critical. You need to know what the market sentiment is as well as what current market conditions are.

For example, is the economy expanding or contracting? Is it a bull or a bear market or a trendless market? Market conditions can have an impact on how a market shock affects prices. Bearish news in a bull market tends to be ignored or exerts a smaller impact and has a shorter duration than bearish news in a bear market. Conversely, bullish news in a bear market might be ignored or exerts a smaller impact and has a shorter duration than the same news would have in a bull or neutral market. Knowing that the effects from a shock might be limited affects your trade horizon. It also has an impact on the sizing of the trade because of the risk associated with the shorter nature of the trade.

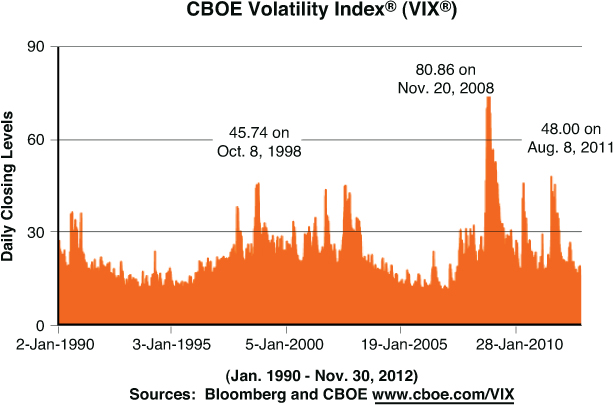

The level of the volatility index (VIX) gives one measure of market sentiment. VIX is also termed the fear index. VIX is a gauge of investor fear in the market place, in general, and the U.S. stock market in particular. Investors fear negative market shocks. Volatility in the market varies over time. Not surprisingly, it was greater during periods of great market stress and uncertainty such as during the Asian financial crisis of 1997–1998, the global financial crisis of 2007–2009, and the European sovereign debt crisis that followed. This is shown in Figure 1.1, which depicts the behavior of the CBOE Volatility Index over the January 1990 through November 30, 2012 period. Not surprisingly, the level of the S&P 500 stock index often varies inversely with the VIX.

(This chart is provided by, and reprinted with permission of, the Chicago Board Options Exchange [CBOE].)

Figure 1.1. The CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) depicts a market measure of uncertainty in the U.S. stock market.

Market shocks can happen anytime. However, you can be ready to profit from them during all periods of market volatility.

What is the value your ideas if they are already priced into the market? What is the value of your ideas if your timing is off? For instance, what value is the knowledge that prices are unsustainable if the bubble continues long enough to cost billions? As analyzed in Chapter 3, “Fads, Fashions, and Bubbles,” according to Ziemba and Ziemba [2008], George Soros’ Quantum Fund managers made precisely this mistake during the Internet bubble. They correctly analyzed that it was a bubble, but anticipated that it would end sooner than it did; the fund lost $5 billion, shorting the bubble too soon.6

Making Trading Decisions

The trading decision process has five dimensions: trade identification, selection, execution, monitoring, and evaluation.

• Trade identification is the art of finding potentially profitable trades.

• Trade selection is the imposition of additional screens on the set of potentially profitable trades to narrow the list. You want to select only the best trades, those you expect to be most profitable for a given level of risk.

• Trade execution occurs after a trade has been decided on, and the order is submitted and executed. This may require more attention for large orders whose execution could adversely impact market prices.

• Trade monitoring requires watching over open trades or positions to determine when to exit a losing position or add to, or exit, a winning position.

• Trade evaluation occurs after open trades have been closed. Traders assess why they entered and exited a trade and how well the trade worked in an attempt to learn from the experience.

Looking Ahead

The remaining chapters discuss the following topics:

• Chapter 2, “Five Simple Questions.” This chapter raises five simple questions associated with any trading catalyst (asking which markets?, which direction?, how much?, how long?, how risky?) and illustrates answers with real-life market examples. It also raises a sixth question—namely, whether the price action in one market will spread to other markets—and discusses the implications of such moves. Through detailed examples, you will discover how to implement trades and profit from the answers to these five questions for future catalysts.

• Chapter 3, “Fads, Fashions, and Bubbles.” This chapter starts off with an example of how markets sometimes get it wrong and then discusses some apparent market bubbles and their trading implications. This chapter discusses several cases of blatant mispricing and irrational rallies. Seeing how some traders attempt to ride bubbles is instructive; from it you can see how to profit and protect yourself during a bubble, and why some observers believe that some of history’s most famous bubbles might not have been bubbles at all.

• Chapter 4, “Earnings and Corporate Announcements.” This chapter discusses market shocks originating from earnings announcements, lawsuits, executive-level changes, merger announcements, among others. Not surprisingly, these announcements can induce sudden shocks in stock prices. Perhaps surprisingly, there are also many instances of the delayed incorporation of information into a stock’s price, which leaves plenty of opportunity for alert traders to prepare for subsequent rallies or breaks.

• Chapter 5, “Rumor Has It.” Rumors affect market prices. This chapter provides lessons for trading off of and protecting yourself from rumors. A case of “buy the rumor, sell the news,” is examined in detail and the ramifications of market shocks caused by rumors and uncertain information are discussed.

• Chapter 6, “Political Economy.” This chapter discusses how elections, expropriations, regulatory actions, and macroeconomic announcements impact financial market prices. Several examples are given and the trading lessons assessed. This chapter also details how central banks precipitate changes in interest rates, exchange rates, and stock prices. Long-term trends created by government action and trading opportunities from government action are also discussed.

• Chapter 7, “Predatory and Insider Trading.” This chapter discusses instances of predatory and insider trading in financial markets. The dangers of both are discussed and the lessons for traders assessed. Understanding the real threat that predatory and insider trading present helps you to better understand the dynamics of the market and how to protect your wealth.

• Chapter 8, “Crashes, Trading Glitches, and Fat-Finger Trades.” This chapter discusses stock market crashes with particular focus on the flash crash in U.S. stock prices on May 6, 2010 and the lesser-known but similar flash crashes in commodity markets during 2011. It also discusses instances of trading glitches and fat-finger trades and assesses the lessons for traders.

• Chapter 9, “Man Versus Machine.” Machines increasingly dominate trading in financial markets. However, individuals can still make money trading. This chapter analyzes common HFT strategies and discusses several strategies for humans to trade successfully in today’s machine-driven markets.

• Chapter 10, “Flight to Safety.” This chapter discusses various flights to safety and how well they perform during turbulent markets and financial crises. There is an extensive analysis of gold, and whether it actually lives up to its reputation as a store of value. Which assets are actually safe? Is investing in “safe” assets really as safe as it seems?

• Chapter 11, “Why Most Traders Lose Money.” Most traders lose money. There are ways for you to avoid succumbing to these mistakes. Several examples are included to illustrate these rules. The importance of loss minimization and prevention is emphasized.

• Chapter 12, “Developing a Trading Game Plan.” One of the reasons why many traders lose is the failure to develop and follow a viable trading game plan. This chapter discusses how individuals can develop a viable trading game plan and provides points of overall strategy, a five-step plan, and trading maxims to live by.

Endnotes

1. Schwager, J.D., Market Wizards: Interviews with Top Traders, New York Institute of Finance, 1989, pp. 285.

2. Demos, T., “‘Real’ Investors Eclipsed by Fast Trading,” Financial Times, April 24, 2012. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/da5d033c-8e1c-11e1-bf8f-00144feab49a.html#axzz2G1BmAtNn.

3. Fottrell, Q., “Marijuana-dispenser stock gets too high.” WSJ MarketWatch, November 19, 2012. http://articles.marketwatch.com/2012-11-19/finance/35251411_1_medical-marijuana-dispensaries-share-prices-day-traders.

4. Ibid.

5. “United States Financial Superpower,” Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook, February 2012, pp. 55. https://www.credit-suisse.com/investment_banking/doc/cs_global_investment_returns_yearbook.pdf.

6. Ziemba, R., and W.T. Ziemba, Scenarios for Risk Management and Global Investment Strategies. New York: Wiley, 2008.