Chapter 21. Enhancement and replacement projects

Most of this book describes requirements development as though you are beginning a new software or system development project, sometimes called a green-field project. However, many organizations devote much of their effort to enhancing or replacing existing information systems or building new releases of established commercial products. Most of the practices described in this book are appropriate for enhancement and replacement projects. This chapter provides specific suggestions as to which practices are most relevant and how to use them.

An enhancement project is one in which new capabilities are added to an existing system. Enhancement projects might also involve correcting defects, adding new reports, and modifying functionality to comply with revised business rules or needs.

A replacement (or reengineering) project replaces an existing application with a new custom-built system, a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) system, or a hybrid of those. Replacement projects are most commonly implemented to improve performance, cut costs (such as maintenance costs or license fees), take advantage of modern technologies, or meet regulatory requirements. If your replacement project will involve a COTS solution, the guidance presented in Chapter 22 will also be helpful.

Replacement and enhancement projects face some particular requirements issues. The original developers who held all the critical information in their heads might be long gone. It’s tempting to claim that a small enhancement doesn’t warrant writing any requirements. Developers might believe that they don’t need detailed requirements if they are replacing an existing system’s functionality. The approaches described in this chapter can help you to deal with the challenges of enhancing or replacing an existing system to improve its ability to meet the organization’s current business needs.

Expected challenges

The presence of an existing system leads to common challenges that both enhancement and replacement projects will face, including the following:

The changes made could degrade the performance to which users are accustomed.

Little or no requirements documentation might be available for the existing system.

Users who are familiar with how the system works today might not like the changes they are about to encounter.

You might unknowingly break or omit functionality that is vital to some stakeholder group.

Stakeholders might take this opportunity to request new functionality that seems like a good idea but isn’t really needed to meet the business objectives.

Even if there is existing documentation, it might not prove useful. For enhancement projects, the documentation might not be up to date. If the documentation doesn’t match the existing application’s reality, it is of limited use. For replacement systems, you also need to be wary of carrying forward all of the requirements, because some of the old functionality probably should not be migrated.

One of the major issues in replacement projects is validating that the reasons for the replacement are sound. There need to be justifiable business objectives for the change. When existing systems are being completely replaced, organizational processes might also have to change, which makes it harder for people to accept a new system. The change in business processes, change in the software system, and learning curve of a new system can disrupt current operations.

Requirements techniques when there is an existing system

Table 21-1 describes the most important requirements development techniques to consider when working on enhancement and replacement projects.

Why it’s relevant | |

Create a feature tree to show changes |

|

Identify user classes |

|

Understand business processes |

|

Document business rules |

|

Create use cases or user stories |

|

Create a context diagram |

|

Create an ecosystem map |

|

Create a dialog map |

|

Create data models |

|

Specify quality attributes |

|

Create report tables |

|

Build prototypes |

|

Inspect requirements specifications |

|

Enhancement projects provide an opportunity to try new requirements methods in a small-scale and low-risk way. The pressure to get the next release out might make you think that you don’t have time to experiment with requirements techniques, but enhancement projects let you tackle the learning curve in bite-sized chunks. When the next big project comes along, you’ll have some experience and confidence in better requirements practices.

Suppose that a customer requests that a new feature be added to a mature product. If you haven’t worked with user stories before, explore the new feature from the user-story perspective, discussing with the requester the tasks that users will perform with that feature. Practicing on this project reduces the risk compared to applying user stories for the first time on a green-field project, when your skill might mean the difference between success and high-profile failure.

Prioritizing by using business objectives

Enhancement projects are undertaken to add new capabilities to an existing application. It’s easy to get caught up in the excitement and start adding unnecessary capabilities. To combat this risk of gold-plating, trace requirements back to business objectives to ensure that the new features are needed and to select the highest-impact features to implement first. You also might need to prioritize enhancement requests against the correction of defects that had been reported against the old system.

Also be wary of letting unnecessary new functionality slip into replacement projects. The main focus of replacement projects is to migrate existing functionality. However, customers might imagine that if you are developing a new system anyway, it is easy to add lots of new capabilities right away. Many replacement projects have collapsed because of the weight of uncontrolled scope growth. You’re usually better off building a stable first release and adding more features through subsequent enhancement projects, provided the first release allows users to do their jobs.

Replacement projects often originate when stakeholders want to add functionality to an existing system that is too inflexible to support the growth or has technology limitations. However, there needs to be a clear business objective to justify implementing an expensive new system ([ref063]). Use the anticipated cost savings from a new system (such as through reduced maintenance of an old, clunky system) plus the value of the new desired functionality to justify a system replacement project.

Also look for existing functionality that doesn’t need to be retained in a replacement system. Don’t replicate the existing system’s shortcomings or miss an opportunity to update a system to suit new business needs and processes. For example, the BA might ask users, “Do you use <a particular menu option>?” If you consistently hear “I never do that,” then maybe it isn’t needed in the replacement system. Look for usage data that shows what screens, functions, or data entities are rarely accessed in the current system. Even the existing functionality has to map to current and anticipated business objectives to warrant re-implementing it in the new system.

Trap

Don’t let stakeholders get away with saying “I have it today, so I need it in the new system” as a default method of justifying requirements.

Mind the gap

A gap analysis is a comparison of functionality between an existing system and a desired new system. A gap analysis can be expressed in different ways, including use cases, user stories, or features. When enhancing an existing system, perform a gap analysis to make sure you understand why it isn’t currently meeting your business objectives.

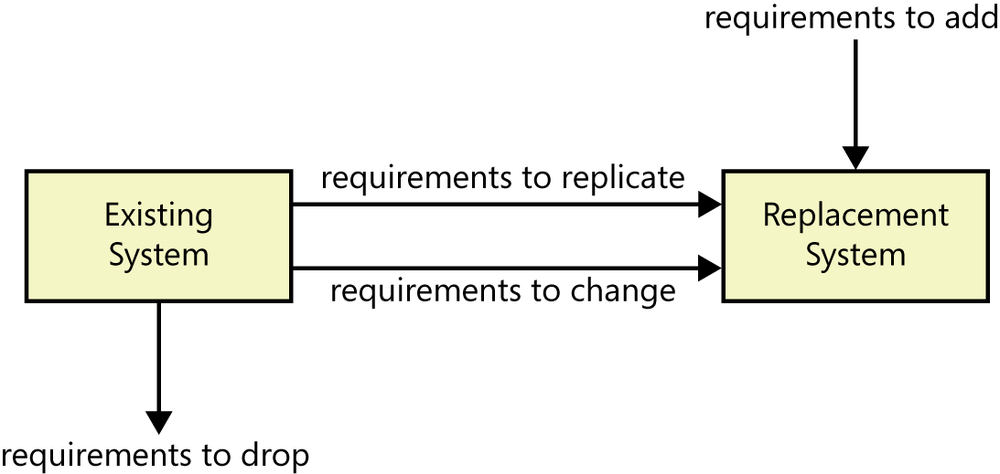

Gap analysis for a replacement project entails understanding existing functionality and discovering the desired new functionality (see Figure 21-1). Identify user requirements for the existing system that stakeholders want to have re-implemented in the new system. Also, elicit new user requirements that the existing system does not address. Consider any change requests that were never implemented in the existing system. Prioritize the existing user requirements and the new ones together. Prioritize closing the gaps using business objectives as described in the previous section or the other prioritization techniques presented in Chapter 16.

Maintaining performance levels

Existing systems set user expectations for performance and throughput. Stakeholders almost always have key performance indicators (KPIs) for existing processes that they will want to maintain in the new system. A key performance indicator model (KPIM) can help you identify and specify these metrics for their corresponding business processes ([ref013]). The KPIM helps stakeholders see that even if the new system will be different, their business outcomes will be at least as good as before.

Unless you explicitly plan to maintain them, performance levels can be compromised as systems are enhanced. Stuffing new functionality into an existing system might slow it down. One data synchronization tool had a requirement to update a master data set from the day’s transactions. It needed to run every 24 hours. In the initial release of the tool, the synchronization started at midnight and took about one hour to execute. After some enhancements to include additional attributes, merging, and synchronicity checks, the synchronization took 20 hours to execute. This was a problem, because users expected to have fully synchronized data from the night before available when they started their workday at 8:00 A.M. The maximum time to complete the synchronization was never explicitly specified, but the stakeholders assumed it could be done overnight in less than eight hours.

For replacement systems, prioritize the KPIs that are most important to maintain. Look for the business processes that trace to the most important KPIs and the requirements that enable those business processes; these are the requirements to implement first. For instance, if you’re replacing a loan application system in which loan processors can enter 10 loans per day, it might be important to maintain at least that same throughput in the new system. The functionality that allows loan processers to enter loans should be some of the earliest implemented in the new system, so the loan processors can maintain their productivity.

When old requirements don’t exist

Most older systems do not have documented—let alone accurate—requirements. In the absence of reliable documentation, teams might reverse-engineer an understanding of what the system does from the user interfaces, code, and database. We think of this as “software archaeology.” To maximize the benefit from reverse engineering, the archaeology expedition should record what it learns in the form of requirements and design descriptions. Accumulating accurate information about certain portions of the current system positions the team to enhance a system with low risk, to replace a system without missing critical functionality, and to perform future enhancements efficiently. It halts the knowledge drain, so future maintainers better understand the changes that were just made.

If updating the requirements is overly burdensome, it will fall by the wayside as busy people rush on to the next change request. Obsolete requirements aren’t helpful for future enhancements. There’s a widespread fear in the software industry that writing documentation will consume too much time; the knee-jerk reaction is to neglect all opportunities to update requirements documentation. But what’s the cost if you don’t update the requirements and a future maintainer (perhaps you!) has to regenerate that information? The answer to this question will let you make a thoughtful business decision concerning whether to revise the requirements documentation when you change or re-create the software.

When the team performs additional enhancements and maintenance over time, it can extend these fractional knowledge representations, steadily improving the system documentation. The incremental cost of recording this newly found knowledge is small compared with the cost of someone having to rediscover it later on. Implementing enhancements almost always necessitates further requirements development, so add those new requirements to an existing requirements repository, if there is one. If you’re replacing an old system, you have an opportunity to document the requirements for the new one and to keep the requirements up to date with what you learn throughout the project. Try to leave the requirements in better shape than you found them.

Which requirements should you specify?

It’s not always worth taking the time to generate a complete set of requirements for an entire production system. Many options lie between the two extremes of continuing forever with no requirements documentation and reconstructing a perfect requirements set. Knowing why you’d like to have written requirements available lets you judge whether the cost of rebuilding all—or even part—of the specification is a sound investment.

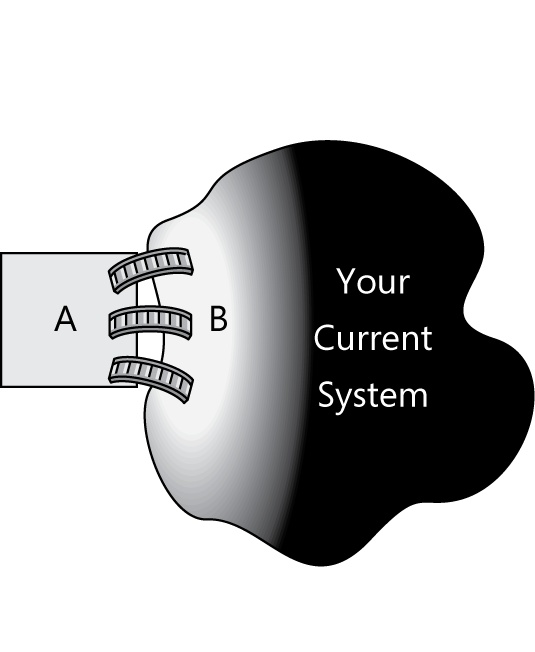

Perhaps your current system is a shapeless mass of history and mystery like the one in Figure 21-2. Imagine that you’ve been asked to implement some new functionality in region A in this figure. Begin by recording the new requirements in a structured SRS or in a requirements management tool. When you add the new functionality, you’ll have to figure out how it interfaces to or fits in with the existing system. The bridges in Figure 21-2 between region A and your current system represent these interfaces. This analysis provides insight into the white portion of the current system, region B. In addition to the requirements for region A, this insight is the new knowledge you need to capture.

Rarely do you need to document the entire existing system. Focus detailed requirements efforts on the changes needed to meet the business objectives. If you’re replacing a system, start by documenting the areas prioritized as most important to achieve the business objectives or those that pose the highest implementation risk. Any new requirements identified during the gap analysis will need to be specified at the same level of precision and using the same techniques as you would for a new system.

Level of detail

One of the biggest challenges is determining the appropriate level of detail at which to document requirements gleaned from the existing system. For enhancements, defining requirements for the new functionality alone might be sufficient. However, you will usually benefit from documenting all of the functionality that closely relates to the enhancement, to ensure that the change fits in seamlessly (region B in Figure 20-2). You might want to create business processes, user requirements, and/or functional requirements for those related areas. For example, let’s say you are adding a discount code feature to an existing shopping cart function, but you don’t have any documented requirements for the shopping cart. You might be tempted to write just a single user story: “As a customer, I need to be able to enter a discount code so I can get the cheapest price for the product.” However, this user story alone lacks context, so consider capturing other user stories about shopping cart operations. That information could be valuable the next time you need to modify the shopping cart function.

I worked with one team that was just beginning to develop the requirements for version 2 of a major product with embedded software. They hadn’t done a good job on the requirements for version 1, which was currently being implemented. The lead BA wondered, “Is it worth going back to improve the SRS for version 1?” The company anticipated that this product line would be a major revenue generator for at least 10 years. They also planned to reuse some of the core requirements in several spin-off products. In this case, it made sense to improve the requirements documentation for version 1 because it was the foundation for all subsequent development work in this product line. Had they been working on version 5.3 of a well-worn system that they expected to retire within a year, reconstructing a comprehensive set of requirements wouldn’t have been a wise investment.

Trace Data

Requirements trace data for existing systems will help the enhancement developer determine which components she might have to modify because of a change in a specific requirement. In an ideal world, when you’re replacing a system, the existing system would have a full set of functional requirements such that you could establish traceability between the old and new systems to avoid overlooking any requirements. However, a poorly documented old system won’t have trace information available, and establishing rigorous traceability for both existing and new systems is time consuming.

As with any new development, it’s a good practice to create a traceability matrix to link the new or changed requirements to the corresponding design elements, code, and test cases. Accumulating trace links as you perform the development work takes little effort, whereas it’s a great deal of work to regenerate the links from a completed system. For replacement systems, perform requirements tracing at a high level: make a list of features and user stories for the existing system and prioritize to determine which of those will be implemented in the new system. See Chapter 29 for more information on tracing requirements.

How to discover the requirements of an existing system

In enhancement and replacement projects, even if you don’t have existing documentation, you do have a system to work from to discover the relevant requirements. During enhancement projects, consider drawing a dialog map for the new screens you have to add, showing the navigation connections to and from existing display elements. You might write use cases or user stories that span the new and existing functionality.

In replacement system projects, you need to understand all of the desired functionality, just as you do on any new development project. Study the user interface of the existing system to identify candidate functionality for the new system. Examine existing system interfaces to determine what data is exchanged between systems today. Understand how users use the current system. If no one understands the functionality and business rules behind the user interface, someone will need to look at the code or database to understand what’s going on. Analyze any documentation that does exist—design documents, help screens, user manuals, training materials—to identify requirements.

You might not need to specify functional requirements for the existing system at all, instead creating models to fill the information void. Swimlane diagrams can describe how users do their jobs with the system today. Context diagrams, data flow diagrams, and entity-relationship diagrams are also useful. You might create user requirements, specifying them only at a high level without filling in all of the details. Another way to begin closing the information gap is to create data dictionary entries when you add new data elements to the system and modify existing definitions. The test suite might be useful as an initial source of information to recover the software requirements, because tests represent an alternative view of requirements.

Encouraging new system adoption

You’re bound to run into resistance when changing or replacing an existing system. People are naturally reluctant to change. Introducing a new feature that will make users’ jobs easier is a good thing. But users are accustomed to how the system works today, and you plan to modify that, which is not so good from the user’s point of view. The issue is even bigger when you’re replacing a system, because now you’re changing more than just a bit of functionality. You’re potentially changing the entire application’s look and feel, its menus, the operating environment, and possibly the user’s whole job. If you’re a business analyst, project manager, or project sponsor, you have to anticipate the resistance and plan how you will overcome it, so the users will accept the new features or system.

An existing, established system is probably stable, fully integrated with surrounding systems, and well understood by users. A new system with all the same functionality might be none of these upon its initial release. Users might fear that the new system will disrupt their normal operations while they learn how to use it. Even worse, it might not support their current operations. Users might even be afraid of losing their jobs if the system automates tasks they perform manually today. It’s not uncommon to hear users say that they will accept the new system only if it does everything the old system does—even if they don’t personally use all of that functionality at present.

To mitigate the risk of user resistance, you first need to understand the business objectives and the user requirements. If either of these misses the mark, you will lose the users’ trust quickly. During elicitation, focus on the benefits the new system or each feature will provide to the users. Help them understand the value of the proposed change to the organization as a whole. Keep in mind—even with enhancements—that just because something is new doesn’t mean it will make the user’s job easier. A poorly designed user interface can even make the system harder to use because the old features are harder to find, lost amidst a clutter of new options, or more cumbersome to access.

Our organization recently upgraded our document-repository tool to a new version to give us access to additional features and a more stable operating environment. During beta testing, I discovered that simple, common tasks such as checking out and downloading a file are now harder. In the previous version, you could check out a file in two clicks, but now it takes three or four, depending on the navigation path you choose. If our executive stakeholders thought these user interface changes were a big risk to user acceptance, they could invest in developing custom functionality to mimic the old system. Showing prototypes to users can help them get used to the new system or new features and reveal likely adoption issues early in the project.

One caveat with system replacements is that the key performance indicators for certain groups might be negatively affected, even if the system replacement provides a benefit for the organization as a whole. Let users know as soon as possible about features they might be losing or quality attributes that might degrade, so they can start to prepare for it. System adoption can involve as much emotion as logic, so expectation management is critical to lay the foundation for a successful rollout.

When you are migrating from an existing system, transition requirements are also important. Transition requirements describe the capabilities that the whole solution—not just the software application—must have to enable moving from the existing system to the new system ([ref115]). They can encompass data conversions, user training, organizational and business process changes, and the need to run both old and new systems in parallel for a period of time. Think about everything that will be required for stakeholders to comfortably and efficiently transition to the new way of working. Understanding transition requirements is part of assessing readiness and managing organizational change ([ref115]).

Can we iterate?

Enhancement projects are incremental by definition. Project teams can often adopt agile methods readily, by prioritizing enhancements using a product backlog as described in Chapter 20. However, replacement projects do not always lend themselves to incremental delivery because you need a critical mass of functionality in the new application before users can begin using it to do their jobs. It’s not practical for them to use the new system to do a small portion of their job and then have to go back to the old system to perform other functions. However, big-bang migrations are also challenging and unrealistic. It’s difficult to replace in a single step an established system that has matured over many years and numerous releases.

One approach to implementing a replacement system incrementally is to identify functionality that can be isolated and begin by building just those pieces. We once helped a customer team to replace their current fulfillment system with a new custom-developed system. Inventory management represented about 10 percent of the total functionality of the entire fulfillment system. For the most part, the people who managed inventory were separate from the people who managed other parts of the fulfillment process. The initial strategy was to move just the inventory management functionality to a new system of its own. This was ideal functionality to isolate for the first release because it affected just a subset of users, who then would primarily work only in the new system. The one downside side to the approach is that a new software interface had to be developed so that the new inventory system could pass data to and from the existing fulfillment system.

We had no requirements documentation for the existing system. But retaining the original system and turning off its inventory management piece provided a clear boundary for the requirements effort. We primarily wrote use cases and functional requirements for the new inventory system, based on the most important functions of the existing system. We created an entity-relationship diagram and a data dictionary. We drew a context diagram for the entire existing fulfillment system to understand integration points that might be relevant when we split inventory out of it. Then we created a new context diagram to show how inventory management would exist as an external system that interacts with the truncated fulfillment system.

Not all enhancement or replacement projects will be this clean. Most of them will struggle to overcome the two biggest challenges: a lack of documentation for the existing system, and a potential battle to get users to adopt the new system or features. However, using the techniques described in this chapter can help you actively mitigate these risks.