Chapter 24. Business process automation projects

Organizations often choose to fully or partially replace manual business processes with software to lower operational costs. In fact, most corporate IT projects involve some amount of business process automation, including the Chemical Tracking System and other projects we have mentioned in this book. Processes can be automated by building a new software system, extending an existing system, or buying a COTS package. If you’re working on a business process automation project, there are several requirements techniques to consider using to mesh the new systems and updated business processes.

Because business process automation is so prevalent in software projects, many of the techniques described elsewhere in this book are relevant. This chapter presents a structure to help you tackle these sorts of projects and points out the techniques from the rest of the book that are most applicable. It also presents some additional techniques that aren’t covered elsewhere in the book.

Here’s an illustration of how business process automation projects sometimes go. One customer of ours had a spreadsheet that used approximately 300 inputs from different sources to calculate a risk profile for loans. The business stakeholders wanted software that would gather the data inputs and run the risk profile calculation, because it took a long time for their risk managers to execute this frequently repeated process. We analyzed where their users spent the bulk of their time on this process and quickly determined that assembling the data that fed into the spreadsheet took the most time. The calculations the spreadsheet performed were nearly instantaneous. The development team already had access to most of the data sources to populate the spreadsheet, so a manageable first phase of the project was to automatically pull that data into the spreadsheet. The business users would continue to manually assemble the rest of the inputs for awhile. In the second phase, development would automate the rest of the data inputs. The team decided they would not build software to replicate the spreadsheet calculations because the calculations were fast enough already.

This case study illustrates a typical business process automation project. The business identified a time-consuming, repetitive activity that they thought could be accelerated with the help of suitable software. Some analysis revealed the bottlenecks and identified possible efficiencies. This led to requirements and project plans for a partial solution that would save the business considerable time, reduce costs, and reduce data input errors.

Modeling business processes

Eliciting requirements to automate business processes begins by modeling those processes. By identifying tasks that users need to accomplish with the system, the business analyst can derive the necessary functional requirements that will let users perform those tasks. The processes that describe how the business currently works are called the as-is processes. Those that describe the envisioned future state of how the business will operate are called the to-be processes.

Using current processes to derive requirements

The following steps will help you model a set of business processes and elicit requirements for an application that automates some or all of them. The sequence of these steps is not always the same, and you might not need all of them on every project. In some cases, the to-be process flows can come earlier in the sequence as a way of driving a gap analysis or to help ensure that the new system is more just than the old system dressed up in a new outfit. In general, though, consider following these steps:

As always with software development, start by understanding the business objectives, so you can link each objective to one or more processes.

Use organization charts to find all of the affected organizations and potential user classes for a future software solution.

Identify all of the relevant business processes involving participation of those user classes.

Document the as-is business processes by using flow charts, activity diagrams, or swimlane diagrams. Any of the three models is a practical choice for representing users’ tasks. Users can quickly read them and point out any missing or incorrect steps, roles, or decision logic ([ref013]). You’ll need to judge how far down into the as-is modeling you need to drill to get the necessary information to perform the remaining steps in this list.

Analyze the as-is processes to determine the biggest opportunities for improvement from automation. If this is not obvious, you will need to gather some data about how long it takes to execute individual steps or full processes. You can model these measures by using the key performance indicator model (KPIM) described later in this chapter. This step helps identify opportunities and, if a software solution is deemed appropriate, set the scope of the software development part of the project. Make sure you are addressing true bottlenecks in the process, so that accelerating them will speed up the overall process.

For the processes that are in scope for automation, walk through each as-is process flow with the appropriate stakeholders to elicit software requirements to support each step in the flow. The techniques described in Chapter 7 will be valuable during this activity. If applicable, you might also look for industry standards for the process you are modeling, to help you set improvement goals.

Trace the requirements to the process flow steps so that it is obvious if you are missing requirements for any specific steps. If you have process steps without requirements traced to them, confirm that those steps are not being automated as part of the project.

Document to-be process flows to help the business prepare for the new system and to identify any gaps that the new system might leave in their process. You might also create use cases to provide more detail about how users will interact with the new system. This information helps developers ensure that they create a system to meet the business’s expectations and helps users understand what they are getting. The to-be process flows and use cases can be used to develop training materials for the new system and to identify any other transition requirements. This step helps stakeholders to understand not only what is coming, but what manual activities and automated systems need to be unplugged.

Designing future processes first

There is a chicken-and-egg problem with information systems and business processes. In some cases, people expect that building a new system will drive improvements or changes in the processes. However, the way the application is used in practice might not enable the desired business process changes. Process changes involve culture changes and user education that a software system cannot deliver. Some customers believe that the development team is responsible for a successful application rollout and for guiding the implementation of associated business processes. Users won’t embrace a new system just because a developer says to, though.

In many cases, it’s better to devise the new business processes first and then assess the needed changes in your information systems architecture. Properly supporting a new business process might involve changing multiple systems. Thinking about which users will use the system and how they will use it to do their jobs will help you define the correct user requirements, which in turn will maximize user adoption of the new system. Concurrent development of new processes and new applications helps ensure that the two merge nicely.

Modeling business performance metrics

It’s important to understand which business performance metrics are most important to address with business process automation so that the development work can be prioritized. You might have success metrics to use as a starting point from the vision and scope document (see the 1.4 Success metrics section in Chapter 5). If not, the business performance metrics developed here will help complete the vision and scope. For the spreadsheet example earlier in the chapter, you might care about how long it takes to populate the spreadsheet manually and how fast you need it to be in the automated solution.

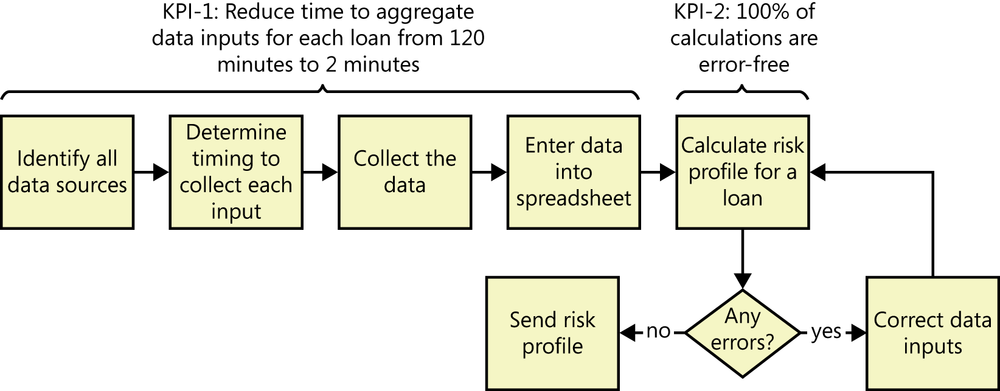

KPIMs associate business processes with their important performance metrics. KPIMs are drawn as flowcharts, swimlane diagrams, or activity diagrams with key performance indicators (KPIs) overlaid on the related steps. Figure 24-1 shows an example KPIM (drawn as a flowchart) for the spreadsheet project to automate a risk profile calculation spreadsheet.

The most important processes to automate are those that have the most important metrics to maintain or improve. Determine a current baseline value for each metric, so that when you automate the process, you can tell if they are improving as desired. Keep in mind that you might degrade certain business performance metrics to improve others. Chapter 14 discusses making trade-offs between quality attributes. The same concept applies here, but in this case the trade-offs are to favor one performance metric over another, perhaps in different parts of the business. Tracing requirements to the process flow steps, which in turn are mapped to KPIs, allows you to prioritize the requirements to be implemented.

You might need to build functionality into the system to periodically measure the relevant KPIs to evaluate the effectiveness of the newly automated solution, raising a warning flag if a KPI falls out of tolerance. In the spreadsheet example, the system could measure how much time it takes to aggregate data inputs to determine if the system is achieving the two-minute goal. If not, further changes might be needed.

Business users often think it’s always best to automate a manual process if you can. However, there are costs associated with all development projects. Business analysis helps you determine which processes are worth automating and which are not. As an example, Seilevel (Joy’s company) uses a COTS solution for managing the sales pipeline and another for managing human resource allocations. We run a report from the sales pipeline tool and manually input the upcoming projects into the resource allocation tool to forecast resource needs. Our consulting manager has to do this at least once a week. It takes him approximately 30 minutes each week to run the sales pipeline report, decide which projects from sales should be transferred, when those projects will start, and how many resources each one needs. We evaluated whether we should enable the integration feature to automatically transfer the data from one tool to the other. Although integrating the tools is as simple as enabling a feature, it would require custom development to automate the decision process our consulting manager goes through. Specifying and automating that decision logic would require more effort than we can justify.

Good practices for business process automation projects

Many of the practices from the rest of this book are important to business process automation projects. Table 24-1 lists the most important practices, describes how they apply to such projects, and indicates where to find more information in other chapters.

Technique | Chapter |

Identify user classes that have processes that might need to be automated. | |

Create or extend data models for information that is being handled manually. | |

Create a roles and permissions matrix to capture security requirements that previously were enforced manually. | |

Identify business rules that must be automated when processes they affect are automated. | |

Create flowcharts, swimlane diagrams, activity diagrams, or use cases to show how users currently perform tasks and how they will perform them after automation. | Chapter 8 and Chapter 12 |

Use data flow diagrams (DFDs) to identify processes that could be automated, and create new DFDs to show how newly automated processes interact with existing parts of the system. | |

Adapt business processes to permit use of a COTS solution. | |

Create trace matrices to map process steps to requirements. |

You will likely apply the concepts from this chapter on almost every information systems project you work on. When you encounter part or all of a business process to be automated, use the framework in this chapter to ensure that you fully understand the goals of automating the process and the requirements to support it. This will help everyone understand user expectations so development can deliver a successful solution that yields the desired business benefits.