Chapter 20. Agile projects

Agile development refers to a set of software development methods that encourage continuous collaboration among stakeholders and rapid and frequent delivery of small increments of useful functionality. There are many different types of agile methods; some of the most popular are Scrum, Extreme Programming, Lean Software Development, Feature-Driven Development, and Kanban. The term “agile development” has gained popularity since the publication of the “Manifesto for Agile Software Development” ([ref015]). Agile methods are based on iterative and incremental approaches to software development, which have been around for many years (for example, see [ref020]; [ref083]; and [ref149]).

The agile development approaches have characteristics that distinguish them from one another, but they all fundamentally champion an adaptive (sometimes called “change-driven”) approach over a predictive (sometimes called “plan-driven”) approach ([ref024]; [ref115]). A predictive approach, such as waterfall development, attempts to minimize the amount of risk in a project by doing extensive planning and documentation prior to initiating construction of the software. The project managers and business analysts make sure that all stakeholders understand exactly what will be delivered before it gets built. This can work well if the requirements are well understood at the outset and are likely to remain relatively stable during the project. Adaptive approaches such as agile methods are designed to accommodate the inevitable change that takes place on projects. They also work well for projects with highly uncertain or volatile requirements.

This chapter describes the characteristics of agile approaches as they relate to the requirements activities for a software project, the major adaptations of traditional requirements practices for an agile project, and a road map of where to find more detailed guidance throughout the rest of the book.

Limitations of the waterfall

Organizations often think of a waterfall development process as involving a linear sequence of activities, where project teams fully specify (and sometimes overspecify) the requirements, then create designs, then write code, and finally test the solution. In theory, this approach has several advantages. The team can catch any flaws in the application’s requirements and design early on rather than during construction, testing, or maintenance, when fixing an error is much more costly. If the requirements are correct up front, it is easy to allocate budget and resources, to measure progress, and to estimate an accurate completion date. However, in practice, software development is rarely that straightforward.

Few projects follow a purely sequential waterfall approach. Even predictive projects expect a certain amount of change and put mechanisms in place to handle it. There is always some overlap and feedback between the phases. In general, though, on waterfall development projects the team puts considerable effort into trying to get the full requirements set “right” early on. There are many possible software development life cycles in addition to waterfall and agile approaches. They place varying degrees of emphasis on developing a complete set of requirements early in the project ([ref164]; [ref024]). A key differentiator across the spectrum between totally fixed, predictive projects and totally uncertain, adaptive projects is the amount of time that elapses between when a requirement is created and when software based on that requirement is delivered to customers.

Large projects that use a waterfall approach are often delivered late, lack necessary features, and fail to meet users’ expectations. Waterfall projects are susceptible to this kind of failure because of the layers of dependency built upon the requirements. Stakeholders often change their requirements during the course of a long project, and projects struggle when the software development teams cannot respond to these changes effectively. The reality is that stakeholders will change requirements—because they don’t know precisely what they want at the beginning of the project, because sometimes they can articulate their vision only after they see something that clearly doesn’t match their vision, and because business needs sometimes change during the course of a project.

Although [ref207] is often credited with being the first to publish the formal waterfall model (though not by that name), he actually presented it in the context of being an approach that is “risky and invites failure.” He identified the exact problem that projects today still experience: errors in requirements likely aren’t caught until testing, late in the project. He went on to explain that the steps ideally should be performed in the sequence of requirements, design, code, and test, but that projects really need to overlap some of these phases and iterate between them. Royce even proposed using simulations to prototype the requirements and designs as an experiment before committing to the full development effort. Modified waterfalls, though, are followed by many projects today, with varying degrees of success.

The agile development approach

Agile development methods attempt to address some limitations of the waterfall model. Agile methods focus on iterative and incremental development, breaking the development of software into short cycles called iterations (or, in the agile method known as Scrum, “sprints”). Iterations can be as short as one week or as long as a month. During each iteration, the development team adds a small set of functionality based on priorities established by the customer, tests it to make sure it works properly, and validates it with acceptance criteria established by the customer. Subsequent increments modify what already exists, enrich the initial features, add new ones, and correct defects that were discovered. Ongoing customer participation enables the team to spot problems and changes in direction early, thereby guiding developers to adjust their course before they are too far down the wrong path. The goal is to have a body of potentially shippable software at the end of each iteration, even if it constitutes just a small portion of the ultimately desired product.

Essential aspects of an agile approach to requirements

The following sections describe several differences in the ways that agile projects and traditional projects approach requirements. Many of the requirements practices applied on agile projects also work well on—and are a good idea for—projects following any other development life cycle.

Customer involvement

Collaborating with customers on software development projects always increases the chances of project success. This is true for waterfall projects as well as for agile projects. The main difference between the two approaches is in the timing of the customer involvement. On waterfall projects, customers typically dedicate considerable time up front, helping the BA understand, document, and validate requirements. Customers should also be involved later in the project during user acceptance testing, providing feedback on whether the product meets their needs. However, during the construction phase, there is generally little customer involvement, which makes it difficult for a project to adapt to changing customer needs.

On agile projects, customers (or a product owner who represents them) are engaged continuously throughout the project. During an initial planning iteration on some agile projects, customers work with the project team to identify and prioritize user stories that will serve as the preliminary road map for the development of the product. Because user stories are typically less detailed than traditional functional requirements, customers must be available during iterations to provide input and clarification during the design and construction activities. They should also test and provide feedback on the newly developed features when the construction phase of the iteration is complete.

It is common to have product owners, customers, and end users participate in writing user stories or other requirements, but these individuals might not all be trained in effective requirements methods. Inexpertly written user stories are likely not sufficient for clear communication of requirements. Regardless of who is writing the user stories, someone with solid business analysis skills should review and edit the stories before the team begins implementing them. Chapter 6 further elaborates on customer involvement on agile projects.

Documentation detail

Because developers have little interaction with customers after construction begins on waterfall projects, the requirements must specify system behavior, data relationships, and user experience expectations in considerable detail. The close collaboration of customers with developers on agile projects generally means that requirements can be documented in less detail than on traditional projects. Instead, BAs or other people responsible for requirements will develop the necessary precision through conversations and documentation when it is needed ([ref118]).

People sometimes think that agile project teams are not supposed to write requirements. That is not accurate. Instead, agile methods encourage creating the minimum amount of documentation needed to accurately guide the developers and testers. Any documentation beyond what the development and test teams need (or that is required to satisfy regulations or standards) represents wasted effort. Certain user stories might have little detail provided, with only the riskiest or highest-impact functionality being specified in more detail, typically in the form of acceptance tests.

The backlog and prioritization

The product backlog on an agile project contains a list of requests for work that the team might perform ([ref118]). Product backlogs typically are composed of user stories, but some teams also populate the backlog with other requirements, business processes, and defects to be corrected. Each project should maintain only one backlog ([ref045]). Therefore, defects might need to be represented in the backlog for prioritization against new user stories. Some teams rewrite defects as new user stories or variants of old stories. Backlogs can be maintained on story cards or in tools. Agile purists might insist on using cards, but they are not practical for large projects or distributed teams. Chapter 27 discusses the product backlog in more detail. Various tools for agile project management, including backlog management, are commercially available.

Prioritization of the backlog is an ongoing activity to select which work items go into upcoming iterations and which items are discarded from the backlog. The priorities assigned to backlog items don’t have to remain constant forever, just for the next iteration ([ref157]). Tracing items in the backlog back to the business requirements facilitates prioritization. All projects, not just agile projects, ought to be managing priorities of the work remaining in their backlog.

Timing

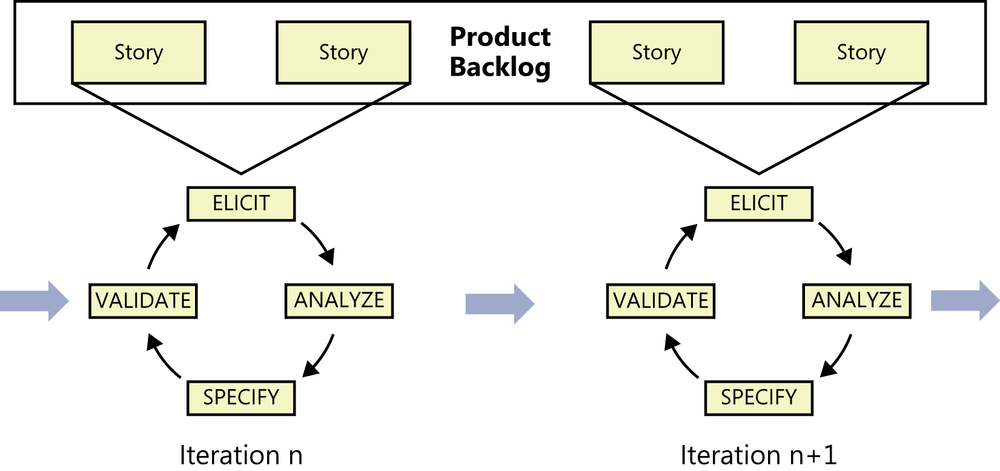

Agile projects require fundamentally the same types of requirements activities as traditional development projects. Someone still needs to elicit requirements from user representatives, analyze them, document requirements of various kinds at appropriate levels of detail, and validate that the requirements will achieve the business objectives for the project. However, detailed requirements are not documented all at once at the beginning of an agile project. Instead, high-level requirements, typically in the form of user stories, are elicited to populate a product backlog early in a project for planning and prioritization.

As shown in Figure 20-1, user stories are allocated to specific iterations for implementation, and the details for each story are further clarified during that iteration. As was illustrated in Figure 3-3 in Chapter 3 requirements might be developed in small portions throughout the entire project, even up until shortly before the product is released. However, it’s important to learn about nonfunctional requirements early on so the system’s architecture can be designed to achieve critical performance, usability, availability, and other quality goals.

Epics, user stories, and features, oh my!

As described in Chapter 8 a user story is a concise statement that articulates something a user needs and serves as a starting point for conversations to flesh out the details. User stories were created specifically to address the needs of agile developers. You might prefer to employ use case names, features, or process flows when exploring user requirements. The form you choose to describe these sorts of requirements is not important; this chapter primarily refers to them as user stories because they are so commonly used on agile projects.

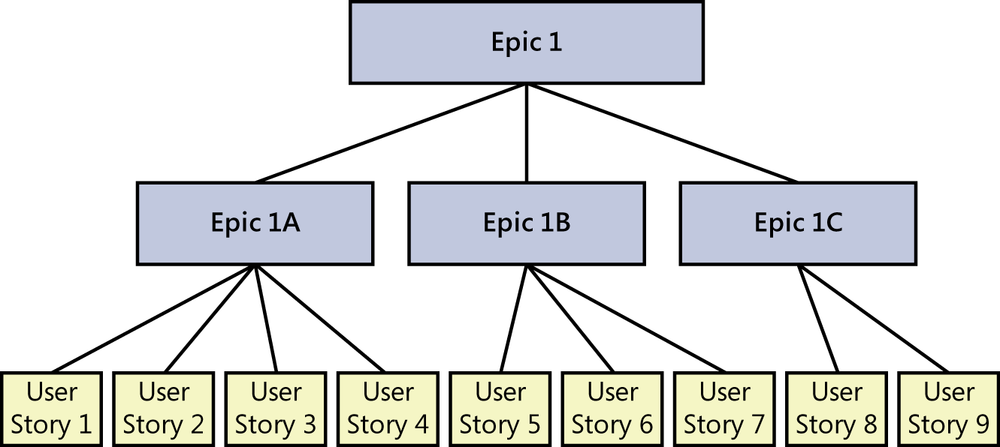

User stories are sized so as to be fully implementable in a single iteration. [ref045] defines an epic as being a user story that is too large to fully implement in a single iteration. Because epics span iterations, they must be split into sets of smaller stories. Sometimes epics are large enough that they must be subdivided into multiple epics, each of which is then split into multiple stories until each resulting story can be reliably estimated and then implemented and tested within a single iteration (see Figure 20-2). Breaking epics down into smaller epics and then into user stories is often referred to as story decomposition ([ref118]).

A feature is a grouping of system capabilities that provides value to a user. In the context of an agile project, features could encompass an individual user story, multiple user stories, an individual epic, or multiple epics. For example, a zoom feature on a phone’s camera might be developed to enable execution of the following two unrelated user stories:

As a mother, I want to take recognizable pictures of my daughter during school performances so that I can share them with her grandparents.

As a birdwatcher, I want to be able to take clear photographs of birds from a distance so that I can identify them.

Identifying the lowest level of stories that still aligns with the business requirements allows you to determine the smallest set of functionality that the team can deliver that provides value to the customer. This concept is often called a minimum (or minimal, or minimally) marketable feature (MMF), as described by [ref061].

Expect change

Organizations know that change will happen on projects. Even business objectives can change. The biggest adaptation that BAs need to make when a requirement change arises on an agile project is to say not, “Wait, that’s out of scope” or “We need to go through a formal process to incorporate that change,” but rather, “Okay, let’s talk about the change.” This encourages customer collaboration to create or change user stories and prioritize each change request against everything else that’s already in the backlog. As with all projects, agile project teams need to manage changes thoughtfully to reduce their negative impact, but they anticipate and even embrace the reality of change. See Chapter 28 for more information about managing requirements change on agile projects.

Knowing that you can handle changes doesn’t mean you should blindly ignore the future and pay attention only to what’s known now. It is still important to look ahead and see what might be coming farther down the road. The developers might not design for every possible future requirement. Given some glimpse of the future, though, they can create a more expandable and robust architecture or design hooks to make it easy to add new functionality.

Change also includes removing items from scope. Items can be removed from an iteration’s scope for various reasons, including the following:

Implementation issues prevent an item from being completed within the current time frame.

Issues discovered by product owners or during testing make the implementation of a particular story unacceptable.

Higher-priority items need to replace less important ones that were planned for an iteration.

Adapting requirements practices to agile projects

Most of the practices described throughout this book can easily be adapted to agile projects, perhaps by altering the timing when they’re used, the degree to which they are applied, or who performs each practice. The International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA) provides detailed suggestions regarding business analysis techniques to apply to agile projects ([ref118]). Many other chapters in this book address how to adapt the practices described in the chapter to suit an agile project. Table 20-1 provides a road map to the specific chapters that address agile projects directly.

Chapter | Topic |

Reaching agreement on requirements | |

The BA’s role on agile projects and who is responsible for the requirements artifacts created | |

Setting and managing the vision and scope | |

User representation | |

User stories | |

Specifying requirements for agile development | |

Modeling on agile projects | |

Identifying quality attributes, especially those needed up front for architecture and design | |

Agile projects and evolutionary prototyping | |

Prioritization on agile projects | |

Acceptance criteria and acceptance tests | |

Managing requirements on agile projects through backlogs and burndown charts | |

Managing change on agile projects |

Transitioning to agile: Now what?

If you’re a business analyst who is new to agile development methods, don’t worry: most of the practices you already use will still apply. After all, both agile and traditional project teams need to understand the requirements for the solutions they build. Following are a few suggestions to help you make the conversion to an agile approach:

Determine what your role is on the team. As described in Chapter 4, some agile projects have a dedicated BA, whereas others have people with different titles who perform business analysis activities. Encourage all team members to focus on the goals of the project, not their individual roles or titles ([ref091]).

Read a book on the agile product owner role so you understand user stories, acceptance tests, backlog prioritization, and why the agile BA is never “finished” until the end of the project or release. One suggested book is Agile Product Management with Scrum ([ref185]).

Identify suggested agile practices that will work best in your organization. Consider what has worked well already with other development approaches in your organization, and carry on those practices. Collaborate with the people currently performing other team roles to determine how their practices will work in an agile environment.

Implement a small project first as a pilot for agile methods, or implement only a few agile practices on your next project.

If you decide to implement a hybrid model that adopts some agile practices but not others, select a few low-risk practices that can work well in any methodology to start. If you are new to agile, bring in an experienced coach for three or four iterations to help you avoid the temptation to revert to the historical practices with which you are comfortable.

Don’t be an agile purist just for the sake of being a purist.