1

Connected media, connected idioms

The relationship between video and electroacoustic music from a composer’s perspective

Editor’s note

This chapter was originally presented at various international conferences between 2006–2008, but was never formally published. Its inclusion within this volume provides a permanent published record of the perspectives and ideas within and reflects the significant influence that the author had upon the editor as an undergraduate student, introducing him to the audiovisual.

This chapter is where this book began.

Introduction

As the enabling technologies for creative work with digital audio now reside on the same computers as those used for video applications, composers have the, relatively affordable, opportunity to ‘connect’ these two digital-media in their creative endeavors. Yet, despite the facilitating role of software interfaces and the inheritance of past experiences in mapping musical gestures to the moving image, the inherent difficulty of an interconnected audiovisual ‘idiom’ soon becomes apparent. The exposition and development of such an idiom represents a stimulating, yet daunting, challenge for both audiences and composers.

Electroacoustic music communities have treasured and pioneered technological advances in electronic and digital media tools. Sound and Image practices may find benefit in seeking to extend into the audiovisual domain the powerful and distinctive traits of a form of art that originally based itself, historically, culturally and aesthetically, on the primacy of the ear.

Strategies adopted by a new breed of – sometimes self-taught – audiovisual composers are informed by their experiences as Electroacoustic composers, sound designers and sound artists, but their very actions also throw the acousmatic paradigm into question. We will leave the darkness of the concert room behind us and reflect upon works articulated through the combination of shifting audible and visible morphologies.

Although this topic can be approached from the viewpoint of the connection between the two ‘physical’ digital media, it becomes apparent that simply connecting two media opens up several interesting questions, not only on the techniques and technologies, but, especially, questions on the ‘connected idioms’, notably how the sonic language and the language of the moving image relate to each other, and what (if any) new combined, integrated idiom they contribute to form. The authors position as a composer ensures that the following discussion is directed and informed by applied experience in practice.

A new trend has emerged within the electoacoustic community during the last twenty years: the combination of Electroacoustic Music soundtracks with video material to form audiovisual works in which the sound and images are more or less equally important. To illustrate the growing status of audiovisual composition within the Electroacoustic Music community I will cite a few historical precedents:

- The International Electroacoustic Music and Sonic Art Competitions of Bourges (www.imeb.net): this competition was founded in 1973 by Françoise Barrière and Christian Clozier and has been for many years one of the most important competitions in this field, certainly in Europe, attracting approximately 200 participants every year from 30 different countries. In the year 2001 for the first time the Bourges competition featured a category for multi-media works.

- The Computer Music Journal (MIT press), published since 1977, covers a wide range of topics related to digital audio signal processing and Electroacoustic Music. The first Video Anthology DVD, containing video works, was published in Winter 2003 as an accompanying disc to issue Vol. 27, Number 4 of the journal.

- The Computer Music Journal issue Vol. 29, Number 4, Winter 2005, was entirely dedicated to topics relevant to Visual Music. This issue also included a second Video Anthology DVD, with selected video works and video examples.

- The biannual Seeing Sound Conference/Festival, hosted by Joseph Hyde at Bath Spa University since 2009. An informal practice-led symposium exploring multimedia work which foregrounds the relationship between sound and image; exploring areas such as visual music, abstract cinema, experimental animation, audiovisual performance and installation practice through paper sessions, screenings, performances and installations, bringing together international artists and thinkers to discuss their work and the aesthetics of audiovisual practice.

- SOUND/IMAGE conference/festival hosted by Andrew Knight-Hill in Greenwich, running annually since 2015, bringing together international practitioners to share concepts and creative approaches to audiovisual composition in concert with exhibitions, screenings and performances. Colliding the worlds of experimental filmmaking and multichannel eletroacoustic composition.

Electroacoustic Music

For the sake of the ensuing discussion we should come, if at all possible, to an agreement of what constitutes ‘Electroacoustic Music’. The reader can refer to many recent writings on the subject as well as a critical review of at least some seminal works from the repertoire (see, for example, Knight-Hill 2020). But in the immediate context, we can take a giant leap forward to consider the following definition:

This definition follows closely Edgard Varèse’s idea of Music as ‘organised sounds’. Another definition could be:

Both these definitions are obviously incomplete, and they over-simplify a form of art which is complex, still evolving, and possibly still trying to define itself amongst the same tidal of globalised fragmentation that characterises all modern electronic arts (and perhaps all human endeavours).

Nevertheless, these definitions give us at least a starting point and some basic principles. More discursively, the concerns of Electroacoustic Music can be identified as follows:

- It has a concern with the ‘discovery’ of sound (recording, synthesis, processing).

- It is a time-based form of art, hence concerned with the evolution and organisation of sounds in time. This raises typical issues of all time-based media such as structure, balance, articulation, progression, direction, etc.

- It uses technology to ‘augment’ composers’ and performers’ control of sound material and audiences’ experience of sound stimuli in an artistic context.

- It assumes the ‘primacy of the ear’ promoted by members of the French school of Musique Concrète (Pierre Schaeffer and others) in the 1950s. This is a cultural attitude both for composers and for listeners. For composers, because they use their hearing ability as primary informant when they ‘compose the sound’ in the studio and when they ‘compose with sound’. For listeners, because in most cases they rely only on their hearing ability (no visual clues) to understand the artistic message in the music. The primacy of the ear is at the core of what we may label the ‘acousmatic paradigm’ of Electroacoustic Music culture.

- It draws together creators and audiences who share a deep fascination with the material of the acoustic space surrounding all of us. Not just the ‘music’ but, rather the ‘sound of it’.

These elements are important because they give us some clues on how to relate to the body of works for electroacoustic sounds and video discussed in this chapter.

The art of visible light – Visual Music

Electroacoustic Music developed alongside innovations and progress in audio technology, the realisation of a quest for a medium of artistic expression that utilised sounds freed from the expectations and cultural references of ‘music’, as we knew it, until the beginning of the 20th century. We could trace a similar path in the development of a non-narrative language of the moving image. In Germany, for example, pioneering film-makers such as Walter Ruttman, Viking Eggeling and Hans Richter developed a type of experimental cinema that articulated abstract shapes moving over time. Oskar Fischinger worked for over 30 years on this type of filmic language and is considered by many the father ofthis type of filmmaking, choreographing abstraction in connection with musical form (Evans 2005).

Experimental cinema of this kind is considered innovative, but was in effect a remediated version of practices that date back a couple of centuries further in time, to the pioneers of ‘Visual Music’.

Visual Music precedes even film. Early examples of gas-lamp Colour Organs date back to the 18th century. Colour organs were instruments that projected coloured light under the control of an organ-like keyboard and were used to provide a visual accompaniment to music performances (Peacock 1988). Such instruments became increasingly sophisticated, in terms of technology, control and visual sophistication, especially with the advent of electricity, but they responded to the same aesthetic quest as their predecessors. Interestingly, there has been a resurgence of interest in Visual Music with exhibitions, screenings and museum galleries in major cities in North America and Europe (see www.iotacenter.org and www.centerforvisualmusic.org for information and catalogues of works in the field, now available on DVDs1).

Convergences

Media art histories of recent years may depict a parallel development of languages of sonic arts, with Electroacoustic Music at the forefront of this movement, and languages of the moving image with Visual Music and experimental non-narrative cinematography on the other side. We can see such a parallel development as an anticipation of an encounter between these disciplines, facilitated by certain key convergences:

Convergence in the type of media

Both the ‘art of sound’ and the ‘art of visible light’ are time-based media. They engage the viewer/listener in a revisited and augmented experience of chronometric time, accomplished through articulation of their time-varying stimuli (audible and visible respectively).

Technological convergence

Both the ‘art of sound’ and the ‘art of visible light’ can inhabit the digital domain, hence their materials can be stored and manipulated by computers. Nowadays the same relatively ‘inexpensive’ desktop computer and even laptops can handle digital audio and, with more difficulty, digital video data. In the solitary reclusion of the music project studio, enabling tools for digital audio-video experimentation reside in the same workstations used for modern computer-music endeavours. It is an opportunity that has been staring at Electroacoustic Music composers for the last 10 years.

Artistic and idiomatic convergences

Both the ‘art of sound’ and the ‘art of visible light’ developed a language that is very experimental, often abstract and breaks away from historically established forms (classical music, figurative art), concentrating on the exploration of the basic matter in the respective media and in the construction of temporal articulations of that matter for artistic purpose (see, for example, Whitney 1960).

Mapping between sound and images

Strategies to combine sound and images have been the subject of study and experimentation for centuries, from Isaac Newton and his correspondences colour-pitch, through the inventors of the colour organs down to the creators of modern music visualiser software such as those supported by iTunes, Windows Media Player and WinAmp (Collopy 2000). Furthermore, psychologists of cognition have been intrigued since the beginning of the 20th century by so-called synaesthesic correspondences correspondences, within which stimuli in one sense modality is transposed, to a different modality (for example, in some individuals certain sounds are perceived with an strong sense of certain taste/flavours).

Many strategies of mapping audio and visual have concentrated on seeking to establish normative mappings between sound pitches and colour hues, in an attempt to create a ‘colour harmony/disharmony’ that can be related to musical consonance/dissonance. Fred Collopy provides a compendium of possible ‘correspondences’ between music and images (see for example a summary of the various ‘colour scales’ developed by thinkers and practitioners over three centuries to associate normatively certain pitches in the tempered scale with certain colour hues [Collopy 2001]).

However, prescriptive mapping techniques, such as colour-scales, quickly become grossly inadequate once the palette of sound and visual material at a composers’ disposal expands. If models for correspondences are to be sought, they need to account for more complex phenomenoloies of audio and video stimuli, far beyond simplistic mappings between, for example, musical pitch and colour hue, or sound loudness and image brightness.

Let us, for a start, introduce a taxonomy of phenomenological parameters of the moving image and of sound, that we may consider a deeper mapping strategy between the two media.2

Phenomenological parameters of the moving image

- Colour – hue, saturation, value (brightness).

- Shapes – geometry, size.

- Surface texture.

- Granularity – single objects, groups/aggregates, clusters, clouds.

- Position/Movement – trajectory, speed, acceleration in the (virtual) 2-D or 3-D space recreated on the projection screen.

- Surrogacy – links to reality, how ‘recognisable’ and how representational visual objects are.

Phenomenological parameters of sound

- Spectrum – pitch, frequencies, harmonics, spectral focus.

- Amplitude envelope – energy profile.

- Granularity – individually discernible sound grains, sequences, aggregates, streams, granular synthesis/reconstruction.

- Spatial behaviour – position, trajectory, speed, acceleration in the 2-D or 3-D virtual acoustic space recreated in a stereo or surround sound field.

- Surrogacy – links to reality, how ‘recognisable’ and how representational our sound objects are.

We can not forget that we are dealing with two time-based media. Therefore, all these preceding parameters must be considered, not just in their absolute values at certain points in time or in averages, but should instead be considered as time-varying entities with individual temporal trajectories.

An audiovisual language can be thus constructed using association strategies relating one or more parameters of audio material to one or more parameters of the visual, including the profile of their behaviour in time. Some of these associations are more naturally justifiable than others (Jones and Nevile 2005: 56). For instance, a mapping between sound frequencies and the size of corresponding visual objects may take into account the fact that objects of smaller size are likely to produce sounds that resonate at higher frequencies. In another example, a mapping strongly rooted on the physics of the stimuli can be established between the amplitude of a sound and the brightness of the associated imagery whereby louder sounds correspond to brighter images, on the basis of the fact that both loudness and brightness are related to the intensity (energy per unit of time and surface) of the respective phenomenon.

The viability and the laws of sound-to-image mappings can represent a fascinating field of research and experimentation. However, with regards to the desirability and the use for creative purposes of, more or less strict, parametric mapping, opinions may vary dramatically between different artists and viewers. On this matter, two interesting viewpoints:

From ‘mapping’ to ‘composing’

The “multi-dimensional interplay of tension and resolution” mentioned by Alves indicates an angle of analysis creativity that is richer than parametric mapping, albeit less rigorous, because the articulation of tension-release is indeed a more useful compositional paradigm than any, more or less formalised, mapping between audio and video material.

Instead of pursuing strict parametric mapping of audio into video or vice versa, composers can aim at the formulation of a more complex ‘language’ based on the articulation of sensory and emotional responses to artistically devised stimuli.

Roger B. Dannemberg observed that composers may opt for connections between sound and moving image that, because they are based on explicit mapping, operate at very superficial levels. He advocates links between the two dimensions that are not obvious, but are somewhat hidden within the texture of the work, at a deeper level. Audiences may grasp intuitively the existence of a link and feel an emotional connection with the work, while the subtlety of this link allows the viewer to relate to the soundtrack and the video track as separate entities, as well to the resulting ‘Gestalt’ of the combination, thus finding the work more interesting and worth repeated visits (Dannemberg 2005: 26).

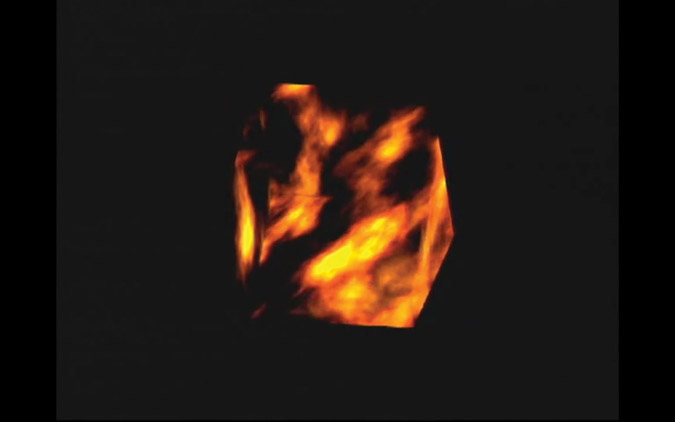

A beautiful example of such approach can be found in Dennis H. Miller’s work Residue (1999) (Figure 1.1). At the onset of this audiovisual composition a moving, semi-transparent cubic solid, textured with shifting red vapours, is associated with long, ringing inharmonic tones on top of which sharp reverberated sounds – resembling magnified echoes of water drops in a vast cavern – occasionally appear. The association between the cube and the related sounds cannot be described in parametrical mapping terms and, in fact, seems at first rather arbitrary. However, the viewer is quickly transported into an audiovisual discourse that is surprisingly coherent and aesthetically enchanting. It is clear that those images and sounds ‘work well’ together although we are not able to explain why, certainly not in terms of parametric mapping. A closer analysis of this work, and others by the same author, reveals that it is the articulation in time of the initial, deliberate, audiovisual association that makes the associations so convincing: we do not know why the red cube is paired with inharmonic drones at the very onset of Residue but, once that audiovisual statement is made, it is then articulated in such a compelling way – by means of alternating repetitions, variations, developments – that the sound-to-image associations become very quickly self-explanatory even without any formal mapping.

Figure 1.1 Still from the opening sequence of Residue by Dennis H. Miller.

Normative mapping approaches to the correspondence between audio and video material can be aesthetically hazardous for composers of Electroacoustic Music. Modern music in general, and Sonic Art in particular, can be very complex, featuring lush sonic textures full of details, spectral and spatial information for the listener to decode and make (artistic) sense of (Dannemberg 2005: 27–28). The listening process, for most works from the Electroacoustic Music repertoire, require repeated, attentive visits and this is often part of the unspoken ‘contract’ between sound artists and their audiences.

When composers engage with audiovisual media they may follow normative approaches and pair complex sound worlds with equally complex visual elements, as a natural extension of the richness and intensity that characterise their musical language. Such an approach would almost inevitably result in artistic redundancy, overloading the viewers’ attention, overestimating their ability to decode the vast amounts of densely articulated material across both domains as they attempt to understand the creative message carried by the combined two. A mantra that all educators repeat so often to their student-composers working with sound and images: ‘less is more’.

This is not to deny complexity. But to recognise that it must be situated within a framework and context which substantiates it. The reader will find that in most successful audiovisual compositions, complex passages are interspersed with moments of release; the viewer’s focus thus moves from global entities with high internal activity (tension), to local entities at lower internal activity (release).3

Electroacoustics, video and reality

Issues of sonic and narrative coherence brought upon by the use of recognisable ‘real’ sounds in Electroacoustic Music are magnified when recognisable imagery is also used in combination with the sounds. There is an enormous creative potential when composers utilise material that, thanks to their representational value, call upon very tangible associations and cultural responses from the audiences. For instance, a generic inharmonic sound can be perceived as a rather abstract object and can acquire a variety of aesthetic connotations depending on the (sonic) context it is immersed in. A particularly recognisable inharmonic sound, for example, a church bell, might function in a similarly reduced way,4 however, such sound is more likely to conjure images and memories of church, faith, religious ritual, spirituality, call, wedding, funeral, mass, joy, mourning, etc. depending on the particular experience – and possibly state of mind – of a particular listener. The dramaturgical implications are very potent and can be used to enhance the ‘theatre’ of a piece, or even as a primary compositional and interpretational paradigm of the work itself (Jonathan Harvey’s Mortuos Plango, Vivos Voco is a case in point).

We can construct works that are recognisably ‘about something’ that is easily understood (Rudi 2005: 37) or use illusory references to a chunk of reality that the viewer can relate to through more or less deep reflection5. These are obviously compositional choices that reflect the artistic intention of the work. This aspect is particularly interesting because it bridges the audiovisual art discussed in this chapter with the cinematography it often strives to separate from. The availability, and affordability, of digital camcorders exerts on audiovisual composers an attraction as irresistible as that posed by microphones to electroacousticians, to access an entire universe of material that can be used for artistic expression. This is inevitably reflected within a body of work that applies elements of audio and video material captured from reality to articulate discourses that are not necessarily, or not entirely, based on narratives and which often attempt to transcend reality itself. In these pieces, the viewer is often informed of the poetic intention of the work via text credits at the beginning of the film or through printed programme notes. However, although such works use cinematographic techniques, they are not ‘film’ in the traditional sense of the word, and nor are they documentaries, although they feature, sometimes extensively, recognisable material filmed with a video camera. Their concrete nature foregrounds their cultural and historical settings which reinforce their audiovisual impact and, vice versa. The sophistication of their audiovisual design may augment the poignancy and the drama implied by the subject matter and its poetic framework. Steve Bird and other researchers at Keele University are working towards a form of audiovisual composition that he calls ‘Electroacoustic Cinema’ and it’s based on the paradigm that “both audio and video are of equal importance and that their relationship must always be synergetic” (Bird 2006). This paradigm is also reinforced by the belief that any form of audiovisual art, even the non-narrative and non-representational ones, should not disregard one and a half centuries of experience in cinematography.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have cruised swiftly through the historical and aesthetic settings within which the ‘art of sound’ and the ‘art of visible light’ have developed during the last century. This, however incomplete excursus, allowed us to consider some convergences in: type of media, technologies and in aesthetics and idiomatic references. These convergences have facilitated, within the Electroacoustic community, an engagement with audiovisual composition, a artform in which parametric audio-visual mapping can provide some interesting, albeit not necessarily comprehensive, strategies for the design and the organisation of material in time. More often however, composers wish to go beyond the ‘connection of two media’ and venture in the murkier, yet more fascinating, business of engaging with the ‘connection of two idioms’. The filmic language, with more than a century and a half of cinemato-graphic heritage, provides an additional creative dimension accessible via modern video cameras which can be used to capture material from the real world as part of the compositional process.

Within the Electroacoustic community, a new breed of, sometimes self-taught, audiovisual composers are operating on the basis of their experience of sound designers and sound artists. However, extending their practices into the combined audiovideo media they also throw the acousmatic paradigm into question. The fact that such a challenge happened without much of a stir, and was embraced by the traditional establishments of Electroacoustic Music (IMEB–Bourges, Computer Music Journal, universities around the world and other centres and institutions), is perhaps an indication that this expansion was somewhat inevitable.

References

- Alves, B. (2005) Digital Harmony of Sound and Light. Computer Music Journal. 29(4). pp. 45–54.

- Autarkeia/Aggregatum (2006) [VISUAL MUSIC] Bret Battey.

- cMatrix10 (2004) [VISUAL MUSIC] Bret Battey.

- Collopy, F. (2000) Colour, Form and Motion. Leonardo. 33(5). pp. 355–360.

- Collopy, F. (2001) Rhythmic Light [Website]. Available online: http://rhythmiclight.com/archives/ideas/correspondences.html [Last Accessed 31/09/05].

- Computer Music Journal. 29(4, Winter 2005). [VISUAL MUSIC].

- Dannemberg, R. (2005) Interactive Visual Music: A Personal Perspective. Computer Music Journal. 29(4). pp. 25–35.

- Evans, B. (2005) Foundations of a Visual Music. Computer Music Journal. 29(4). pp. 11–24.

- Eve’s Solace (2005) [VISUAL MUSIC] Steve Bird.

- Jones, R.; Nevile, B. (2005) Creating Visual Music in Jitter: Approaches and Techniques. Computer Music Journal. 29(4). pp. 55–70.

- Knight-Hill, A. (2020) Electroacoustic Music: An Art of Sound. In: M. Filimowicz (ed.) Foundations of Sound Design for Linear Media. New York: Routledge.

- Mortuos Plango, Vivos Voco (1980) [MUSIC] Jonathan Harvey.

- Peacock, K. (1988) Instruments to Perform Colour-Music: Two Centuries of Technological Experimentation. Leonardo. 21(4). pp. 397–406.

- Pellegrino, R. (1983) The Electronic Arts of Sounds and Light. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold International.

- Pointes Precaires (2004) [VISUAL MUSIC] Diego Garro.

- Residue (1999) [VISUAL MUSIC] Dennis H. Miller – 0:00 to 1:50, dur 1:50.

- Rudi, J. (2005) Computer Music Video: A Composer’s Perspective. Computer Music Journal. 29(4). pp. 36–44.

- Smalley, D. (1986) Spectro-Morphology and Structuring Processes. In: S. Emmerson (ed.) The Language of Electroacoustic Music. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

- video example no.3 (2003) [VISUAL MUSIC] Brian Evans.

- Whitney, J. (1960) Moving Pictures and Electronic Music. Die Reihe. 7. pp. 61–71.