8

The gift of sound and vision

Visual music as a form of glossolalic speech

Introduction

Glossolalic speech (also known as speaking in tongues) uses intonation, accent and rhythm to generate something that approximates recognisable language and yet isn’t (Samarin 1972). Similarly many visual music practitioners have sought to develop a vocabulary that in part echoes the language of music, but again isn’t. This chapter argues that the history of visual music across its various trajectories can be viewed as a quest for a singular audiovisual language. This quest ranging from early experiments in the form of colour organs, up through abstract film and video to contemporary computer-generated work has been doomed to failure owing to the search for absolutes in the audiovisual itself.

Rather than a singular vocabulary based on the inherent properties of sound and image, visual music can be better understood as being created in the mind(s) of the audience at the moment of reception. A glossolalic discourse between practitioner, the work and the audience is generated. This discourse suggests the coherence of a language but is to a degree always indecipherable. It is this locus beyond comprehension that creates the oft-attributed synaesthetic dimension, the potential for visual music to be experienced as immersive or even induce hypnogogic trance. The extent to which this occurs depends on the agency granted the audience as a glossolalic discourse might encourage active participation and reflexive self-awareness, or immersive surrender.

To understand the glossolalic it is useful to first undertake an examination of the various quests to define a singular language, as these reveal not the absolutes, certainties and correlations that creators often seek, but rather a far more arbitrary dynamic between sound and image. This may include counterpointing, synthesis and dissonance made sense of by an audience through a process of audiovisual adhesion. Whilst technological developments have historically facilitated new modes of expression in visual music, it isn’t until the underlying paradigm shifts from a focus on the audiovisual itself to a model that embodies and foregrounds the role of the audience that the quest for a single language is replaced by a fluid and glossolalic syntax.

Which colour is middle C?

When defining visual music a two-way translation or equation between the senses is commonly offered as in ‘seeing with sound’ or ‘hearing in colour’. This model can be traced back to Aristotle, but it was Newton in the 17th century who drew up a diagram equating the colour spectrum to the musical tones in an octave (van Campen 2008: 46). These ideas found physical expression in Castel’s 1761 prototype for an ocular ‘harpsichord for the eyes’, and the subsequent variations on the colour organ developed in the 19th and 20th centuries by Rimington, Scriabin, and Wilfred (Rogers 2013: 64).

Figure 8.1

Newton’s colour scale (1675).

Source: Newton Isaac (1675), Hypothesis explaining the properties of light. In: Thomas Birch, The History of the Royal Society, vol. 3 (London: 1757), pp. 247–305, 263.

Colour organs are predicated on a defined relationship between specific colours and particular notes. However, the various practitioners and inventors were unable to agree on which pitch equals which colour. For Castel middle C was blue as to him “it sounded blue”, whilst Scriabin believed C to be red and Rimsky-Korsakov argued it should be white, though both Scriabin and Rimsky-Korsakov did agree that D major was yellow (Wilfred 1947: 248; Cook 1998: 35).

Malcolm Le Grice (2001: 270) observed that if examined from a simple physics perspective colour and musical harmony clearly do not operate on the same principles. Le Grice (2001: 271) does argue that “colour and music are able to transform existing meanings and create new ones”, especially when the visual element is removed from representation to abstraction, and these new meanings “belong to the viewer” becoming part of “a dynamic process”. Le Grice shifts the debate from a search for colour notational equivalence to the individual’s interaction with the work. By doing so this grants a degree of agency albeit in a context that is socially and culturally defined.

Sound and the moving image

The practical development of Castel’s colour organ was hampered by the technological limitations of the day. The invention of film at the end of the 19th century, and then in the 1920s of a reliable method for synchronising moving images with sound brought new temporal dimensions and possibilities to the audiovisual.

Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Grigori Alexandrov’s ‘Statement on Sound’ (1928/1985: 83) see synchronised sound as a double-edged sword. Synchronised sound has the potential to expand the language of cinema, but could also detract from it if filmmakers adopt the “path of least resistance” – that is using sound to create the “illusion” of “talking people” or “of audible objects”. The ‘Statement’ identifies a fundamental characteristic of the audiovisual – that sound and moving image are inherently adhesive. Given any hint of simultaneity sound and image will appear in the mind of the viewer to adhere, creating a causal link between the seen and heard. To counter this tendency towards adhesion and illusion the Russian filmmakers argue for an act of resistance on the part of filmmakers through the use of non-synchronsiation, to be followed by a more sophisticated counterpointing of audiovisual elements.

Michel Chion’s (1994) concepts of ‘synchresis’ and ‘added value’ could be viewed as logical developments of the principles laid out in the ‘Statement’. Despite Chion’s background as assistant to Pierre Schaeffer, and as noted composer of musique concrete the examples used in Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen (1994) are largely drawn from narrative films, films that suffer from the problem predicted in the ‘Statement’ of using sound and synchronised dialogue as part of a broadly illusory strategy. Chion’s analysis reveals how sound works within the sealed environment of mainstream cinema, but the applicability of his theories to visual music is limited by the constraints of narrative, presuming illusory cinema as given. In contrast, having identified adhesion as the key audiovisual mechanism the ‘Statement’ seeks to argue for ways to problematise its use so as to engage the audience in an active process of generating meaning.

For visual music adhesion offers opportunities and dangers. That sound/music and image should combine so easily is a compositional asset. Almost any moving image sequence if married with a soundtrack will produce some form of adhesion, the visual music equivalent of the “path of least resistance”. The examples given in the ‘Statement’ of “talking people” or “of audible objects” relate to representational imagery, and in this context adhesion will create a causal link between the on-screen action and the sound heard. For example, an image of a glass hitting the ground is perceived as being the source of the smashing sound heard from the speaker.

Within visual music, adhesion and causality take place in a more complex and conflicted fashion, particularly if the imagery is animated or abstract. Moving and plastic shapes will tend to adhere to changes in tempo, pitch and velocity. This may be read causally as either the imagery being choreographed by the music, or as the sound responding to the dynamics of the form. From this flows many of the quests at establishing universal principles. ‘Seeing with sound’, or ‘hearing in colour’ spring not from the inherent qualities of the material, but from attempts made by the viewer and composer at adhesion.

If non-synchronisation was an initial blunt response to the dangers of adhesion both Pudovkin (1929) and Eisenstein (1949) were each to develop the concepts outlined in the ‘Statement’ advocating forms of asynchronism and counterpointing. This located sound and vision as juxtaposed on parallel tracks with punctuated rather than continuous adhesion.

Two examples of the asynchronous approach in visual music are Len Lye’s A Colour Box (1935), and Le Grice’s Berlin Horse (1970). In both works the music (Cuban jazz in the case of Lye, and piano loops by Brian Eno for Le Grice) provides a sense of propulsive syncopated rhythm. The audiovisual elements are not synchronised to any specific sound, beat or on-screen action. Rather, fleeting moments of adhesion occur between the treated footage of horses and Eno’s piano loops (Le Grice), and the dance rhythms and abstract colour shapes (Lye). Asynchronism is not reliant on any particular technology, its inherently glossolalic aspect lies in individual audience members perceiving different moments of adhesion, each generating their own readings. Such confluences are to an extent arbitrary but distinguished from the random for if asynchronism is to ‘work’ an appeal to shared tempos, rhythm, and what might be described as sympathetic visual and musical gestures is required.

The development of sound film created the potential for a direct physical relationship between the audio and the visual in the form of the optical track. Though designed to reproduce spoken dialogue and music Arseny Avraamov in Russia, and Oskar Fischinger in Germany (amongst others) discovered that by drawing or photographing lines and shapes directly onto the optical track one could synthetically create sound (James 1986: 81). What Guy Sherwin (Sherwin and Hegarty 2007: 5) describes as “an accident of technological synaesthesia” is produced when the image on the optical track coincides with the projected frame.

One devotee of optical sound was Norman McLaren who in Pen Point Percussion (1951) outlines the process of making a work, but does not (nor seemingly ever did) address the aesthetic ramifications of the simultaneous projection of optical sound and the source image. Lis Rhodes, working at the London Filmmakers Co-operative in London in the 1970s was more forthright. In an interview at the time of the installation of her piece Light Music (1975–77) in Tate Modern’s Tanks, Rhodes (2012) commented that in Light Music “what you see is what you hear”. This moves beyond causality to the suggestion of a strict equivalence.

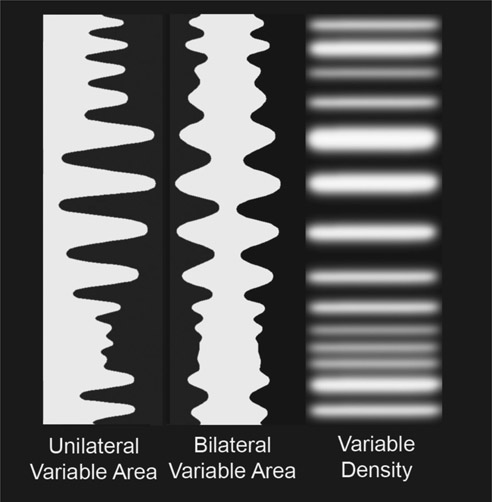

Just as with the arguments over which colour middle C might be, unequivocal equation is called into question by the existence of multiple optical sound mechanisms (see Figure 8.2). That the unilateral, bilateral and variable density methods each reproduce the same sound, but with three different shapes denies an absolute correlation between optical sound and image.

Figure 8.2

Optical sound formats (2019) by Philip Sanderson.

Commenting on the version of Light Music shown in the Tate’s Tanks, Hamlyn (2011: 168) describes “a cacophonous interplay of direct and reflected sound”, with the hard concrete walls of the tanks creating a “partial de-synchronisation of sound and image” experienced dynamically by the audience as they move in and around the two projectors. It is this asynchronous element that when combined with the element of performativity makes the work come to life. The material of Light Music might suggest equivalence but the experience of it is all about audience participation and individual interpretation.

Arbitrary logic – from analogue to digital

Rather than attempting to correlate pitch with colour a broader musically analogous approach was adopted in the 1920s by a milieu of European artists and filmmakers including Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling, Paul Klee and Eisenstein. The musical form that found favour was the Bach fugue whose polyphonically recurring motifs acted as a model for the spatial location of abstract visual elements in Richter’s Rhythmus ’21 (1921–1924), and Eggeling’s Diagonal-Symphonie (1924) (Robertson 2009: 16–22). It was an idealised model as the analogy sought was not with any specific Bach fugue. For though seeking a structure through music, the music then becomes to a degree redundant. Rees (1999: 37) comments “The (musical) metaphor, or analogy, is made the stronger by Eggeling’s insistence that his film (Diagonal-Symphonie) be shown silent”.

By incorporating temporal and multi-dimensional aspects the model was a development from the colour organ, however once again the project was bedevilled by the ‘quest’ for absolutes with Richter and Eggeling believing that they were engaging in the discovery of a universal language of artistic production (Cook 2011).

The desire for an overarching paradigm governing audiovisual correlations continued throughout the 20th century, and if anything the development of new technologies led various practitioners to renew the quest with more vigour. Signifi-cant in this were the brothers James and John Whitney who built a range of bespoke analogue equipment that enabled them to create visual music pieces such as Five Film Exercises (1941–1944). It was natural that once digital computers became available John Whitney would use them, and Arabesque (1975) is an early example of the combination of digital computer-generated graphics with instrumental music. Whitney’s work was underpinned by a return to musica universalis, “I tried to define and manipulate arrays of graphic elements, intending to discover their laws of harmonic relationships” (Whitney 1980: 40–44). Like Richter and Eggeling who sought a universal language of the arts, Whitney (1980) believed that there was a set of unifying principles based upon complimentary ratios that governed both music and graphic form. Whitney saw the computer as a means of actualising these mathematical relationships as it could “manipulate visual patterns in a way that closely corresponds in a manner in which musical instrumentation has dealt with the audio spectrum” (Whitney 1971: 1382–1386).

Whitney’s insights prefigure observations by Le Grice (2001: 268), and Lev Manovich (2001: 52) about digital sound and image. Once transformed into digital data, Le Grice notes that all media “whether visual, auditory or textual” is represented numerically and thus becomes interchangeable, and Manovich observes that as data it also becomes programmable.

One must be wary of technological determinism, but whilst Diego Garro (2005: 4) argues the increasing sophistication of software and the power of computers does not in and of itself “provide any significant aesthetic breakthrough”, treating sound and images as data sets to be manipulated has opened up innumerable possibilities. Crucially, the arbitrary and glossolalic tendencies of visual music are revealed and enhanced by the plurality of syntax facilitated by the many opportunities for digital audiovisual correlations, combinations and permutations.

In my own practice in the early 2000s I investigated the possibilities offered by digital mapping to test the visual music tropes of ‘seeing what you hear’ (or vice versa), and seeing how far one might ‘play’ with adhesion and causality. Quadrangle (2005) takes as its starting point Richter’s Rhythmus ’21 (1921–1924), and similarly uses a white square whose spatial movements are mapped to a numerical sequence produced by a Max 5 (Cycling 74) patch. This digital information is also mapped via MIDI, to a synthesiser. The patch is designed to create random staccato bursts of data, and as the electronic music starts and stops, so simultaneously the square performs a synchronised spatial choreography.

Over the course of the piece the musical mapping remains constant whilst the visual mapping changes. So an increase in value of say 120 always produces a rise in frequency of an octave, but in one section this will correspond with the white square’s movement across the screen from left to right, whilst in another it causes the rotation of the square by 360 degrees. The intention is that just as the audience begins to adhere one set of sound and image correlations the parameters switch, thereby necessitating a recalibration to a new syntax.

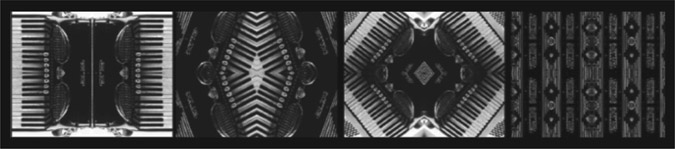

In A Rocco Din (2004) (see Figure 8.3) an image of an accordion is dissected and re-arranged using the digital data derived from a piece of accordion music. The bass and treble parts are mapped to different visual parameters creating synchronised but contrary visual motion. Causality is questioned as the viewer is invited to ask – is the accordion playing the music, or the music playing (the image of) the accordion?

Figure 8.3 A Rocco Din (2004) by Philip Sanderson.

By using the simple tool of digital mapping to question the oft-cited visual music principles of equation, the role of the audience is foregrounded. I explored different variations on switching mapping parameters across a number of short pieces, employing both abstract and representational imagery. This was followed by works such as Kisser (2007), and Tracking (2017) which combine reciprocally evolving granular synthesis audio and atomised imagery creating a wider glossolalic framework.

Sonic sensibilities – electroacoustic visual music

One consequence of the technological convergence of sound and image has been the number of electroacoustic composers seeking to apply the techniques and aesthetics of electroacoustic music to visual music. Like ‘visual music’ the term ‘electroacoustic music’ covers a range of practices, but two elements are key to a definition, the first regards process. Andrew Knight-Hill (2019: 303) argues that the electroacoustic is defined less by a specific aesthetic style and more by “the methods and practices, which make it possible”.

Complimenting process is an equal focus on reception, for at some level all electroacoustic music is underpinned by Schaeffer’s (1966) concept of the ‘acousmatic’, a form of ‘reduced listening’. These two complimentary elements in part explain why the involvement of electroacoustic music composers in visual music has increased awareness and interest in the role of the audience and their perception in the ‘making’ of visual music. A further factor may be that electroacoustic visual music contains an inherent contradiction for ‘reduced listening’ suggests an absence of the visual rather than its addition. One way to avoid accusations of redundancy is by incorporating the audience experience as central to the project. To understand how this works in practice it is worth examining a series of visual music pieces entitled Estuaries 1–3 (2016–2018) by the electroacoustic visual music composer Bret Battey.

In Estuaries Battey employs two twin processes with the imagery produced from a visualisation of the Nelder-Mead method, and the audio created by the generative Nodewebba software. The Nelder-Mead method is a simplex search algorithm that can be employed to find an optimal value be it a minimum or maximum (Singer and Nelder 2009). In Estuaries the Nelder-Mead method is used to locate the brightest points in a source image. In so doing this creates an evolving sequences of fluttering light patterns that dance across the screen. The unpredictability and self-determination makes the patterns akin to some natural phenomena. The Nodewebba software designed by Battey in Max 8 echoes the Nelder-Mead method. This mathematically based generative music tool uses a number of mutually influencing and interlocking patterns to create self-improvisatory musical sequences (see Chapter 18 for a full exposition).

There appears to be no direct parametric mapping of data in Estuaries, instead loosely reciprocal processes determine both parts of the audiovisual. The slowly evolving sound and image movements mirror each other, shifting in and out with fleeting moments of adhesion. In certain sections imagery and music are brought into tighter synchronisation with adhesion heightened by specific moments of punctuation. For example towards the end of Estuaries 3 a series of piano-like tones find an echo on the screen in the form of green bars that move in time with the notation from left to right.

Interestingly whilst Battey is approaching visual music using a methodology derived from the electroacoustic there are many echoes of the asynchronous model employed by Lye in Colour Box, and Le Grice in Berlin Horse. Whitney is also a reference point in terms of a shared interest in mathematical principles. The key difference is whereas Whitney believed there to be universal harmonic ratios between sound and image Battey (writing in a paper with Fisschman) (2016: 73) draws on the paradigm of Rudolf Arnheim’s isomorphism in articulating “a mix of clear correspondences of localized phenomena and higher order intuitive alignment”. Battey is not alone in adopting elements of a Gestalt approach as Knight-Hill (2013) has studied in some detail the factors affecting audience interpretations and responses to electroacoustic visual music in a range of different contexts. In this way electro-acoustic visual music composers have shifted the paradigm away from the quest for an absolute language to a model in which the reception by each member of the audience is central.

Conclusion – the entrancement of the audience

Marcel Duchamp’s (1957: 140) view of the importance of the audience’s role in making an artwork was that “All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualification and thus adds his contribution to the creative act”. Incorporating the viewer as an integral part of the realisation of a work is key to understanding glossolalic communication in visual music.

If the relationship between audiovisual data is not fixed by universals the only laws governing such relationships are those “determined by the composer” (Garro 2005: 4). Thus of all the artforms, visual music arguably makes the audience work the hardest in the collaborative process.

Samarin’s (1972: 120) analysis of the structure of glossolalia identifies the use of elements of language such as vowels, consonants and syllables. “Variations in pitch, volume, speed and intensity” create realistic word and sentence-like structures with a “language-like rhythm and melody” (Samarin 1972: 239). This internal flexible structure elevates glossolalia from being just nonsense, providing a conduit for language-like communication. In response to the failed project of establishing a universal absolute language for visual music glossolalia offers a model for understanding the multi-layered pluralities of visual music and its reception.

Foregrounding the role of the audience does not necessarily grant agency and the glossolalic discourse generated around a work may seek to immerse in much the same way that ‘speaking in tongues’ is used in a religious setting. The total effect of the complex syntax used by visual music composers can be disorientating. In such circumstance audiences may choose to simply ‘surrender’ rather than engage reflexively. This can lead to the oft-attributed synaesthetic dimension in which the illusion of sensory fusion takes place. It is not surprising that terms such as ‘trippy’ or ‘dreamlike’ are often found in the comments section of online postings of visual music videos.

Whilst the condition of visual music is inherently glossolalic, immersive synaesthesia is not a given. The artist can use a number of strategies to encourage self-reflexive participation, for example disrupting adhesion. This was seen in the analysis of Rhodes’s Light Music where despite the tight audiovisual adhesion of the material the performativity of the installation allows a reflexive role for the audience. Battey’s Estuaries series is immersive, but the range of visual music syntax employed encourages the viewer into an awareness of their perceptual processes. Within my own practice a space for active engagement has been sought by deploying an anti-illusionist methodology in the digital domain.

Nonetheless even when an artist seeks to encourage agency this can pose challenges as one is not always in control of the dynamics of reception. The commentary on the works discussed was made after several viewings, and it is only then one begins to unpick the structures and dynamics. It is an anomaly that unlike recorded music where repeated plays are the norm one may see a visual music piece only once or twice at a festival or conference. Works are screened in these contexts as part of longer programmes leading to a cumulative sensory effect. Online and DVD copies of works are increasingly available. Though these rarely offer the same experience in terms of scale and resolution, this can be an advantage allowing one to comprehend the compositional dynamics. Having seen many ‘classics’ of visual music firstly in a cinema and then online, one’s appreciation of them when seen again in an auditorium is all the greater.

One can perhaps talk of three viewing experiences. Firstly, an initial glossolalic viewing in an auditorium when a work communicates, but in a way that may overwhelm the senses. Secondly an online screening less satisfying aesthetically, but informative in terms of decoding the mechanisms of a piece. Then thirdly, an informed viewing in an auditorium, which is still glossolalic but reflexive rather than involuntary.

Glossolalic discourse is a complex process in which numerous factors come into play. This includes aspects of audiovisual adhesion, asynchronism, counterpointing, synthesis and dissonance. Rather than a surrender to subjectivity the glossolalic articulates a unique combination, the gift of sound and vision. The artist’s role is pivotal not only in terms of composition, but also in determining the degree to which a work either confounds the audience, or reflexively engages its participation.

Bibliography

- Andean, J. (2014) Sound and Narrative: Acousmatic Composition as Artistic Research. Journal of Sonic Studies. 7. Available online: www.researchcatalogue.net/view/558896/558922 [Last Accessed 20/04/19].

- Battey, B.; Fischman, R. (2016) Convergence of Time and Space. In: Y. Kaduri (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Image in Western Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Campen, C. van. (2008) The Hidden Sense: Synesthesia in Art and Science. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Chion, M. (1994) Audio-Vision. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Cook, M. (2011) Visual Music in Film, 1921–1924: Richter, Eggeling, Ruttman. In: C. de Mille (ed.) Music and Modernism. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Cook, N. (1998) Analysing Musical Multimedia. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cycling 74 (2019) Max/MSP/Jitter. Available online: https://cycling74.com. [Last Accessed 18/04/19].

- Duchamp, M. (1989 [1957]) The Creative Act. In: M. Sanouillet; E. Peterson (eds.) The Writings of Marcel Duchamp. Boston, MA: Da Capo Press.

- Eisenstein, S.M. (1949) Film Form: Essays in Film Theory. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Eisenstein, S.M.; Pudovkin, V.I.; Aleksandrov, G.V. (1985 [1928]) A Statement on Sound. In: E. Weis; J. Belton (eds.) Film Sound: Theory and Practice. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Elder, R.B. (2007) Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling: The Dream of Universal Language and the Birth of the Absolute Film. In: A. Graf and D. Scheunemann (eds.) Avant-Garde Film. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Garro, D. (2005) A Glow on Pythagoras’ Curtain: A Composer’s Perspective on Electroacoustic Music with Video. Available online: www.ems-network.org/spip.php?rubrique34.

- Goodman, F.D. (1972) Speaking in Tongues: A Cross-Cultural Study of Glossolalia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hamlyn, N. (2003) Film Art Phenomena. London: British Film Institute.

- Hamlyn, N. (2011) Mutable Screens: The Expanded Films of Guy Sherwin, Lis Rhodes, Steve Farrer and Nicky Hamlyn. In: A.L. Rees; D. White; S. Ball; D. Curtis (eds.) Expanded Cinema: Art, Performance, Film. London: Tate Publishing.

- James, R.S. (1986) Avant-Garde Sound-on-Film Techniques and Their Relationship to Electro-Acoustic Music. The Musical Quarterly. 72(1). Oxford Academic. pp. 74–89.

- Knight-Hill, A. (2013) Interpreting Electroacoustic Audio-Visual Music. PhD Thesis. Leicester: De Mont-fort University.

- Knight-Hill, A. (2019) Electroacoustic Music: An Art of Sound. In: M. Filimowicz (ed.) Foundations of Sound Design for Linear Media. New York: Routledge.

- Le Grice, M. (2001) Experimental Cinema in the Digital Age. London: British Film Institute.

- Manovich, L. (2001) The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Pudovkin, V.I. (1985 [1929]) Asynchronism as a Principle of Sound Film. In: E. Weis; J. Belton (eds.) Film Sound: Theory and Practice. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Rees, A.L. (1999) A History of Experimental Film and Video: From the Canonical Avant-Garde to Contemporary British Practice. London: British Film Institute.

- Rhodes, L. (2012) Lis Rhodes: Light Music (Page Contains Video of Interview with Rhodes). Available online: www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern-tanks/display/lis-rhodes-light-music [Last Accessed 20/04/19].

- Robertson, R. (2009) Eisenstein on the Audiovisual: The Montage of Music: Image and Sound in Cinema. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Rogers, H. (2010) Visualising Music: Audio-Visual Relationships in Avant-Garde Film and Video Art. Saabrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing.

- Rogers, H. (2013) Sounding the Gallery: Video and the Rise of Art-Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Samarin, W.J. (1972) Tongues of Men and Angels: The Religious Language of Pentecostalism. New York: Macmillan.

- Schaeffer, P. (1966) Solfege de l’objet Sonore. Paris: Institut National de l’Audiovisuel and Groupe de Recherches Musicales.

- Sherwin, G.K.; Hegarty, S. (2007) Optical Sound Films 1971–2007. London: Lux.

- Singer, S.; Nelder, J. (2009) Nelder-Mead Algorithm. Scholarpedia. 4(7). p. 2928.

- Whitney, J.H. (1971) A Computer Art for the Video Picture Wall. In: IFIP Congress (2). Ljubljana IFIP. pp. 1382–1386.

- Whitney, J.H. (1980) Digital Harmony: On the Complementarity of Music and Visual Art. Peterborough, NH: Byte Books and McGraw-Hill.

- Wilfred, T. (1947) Light and the Artist. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 5(4). Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 247–255.

Filmography

- Arabesque (1975) [FILM] dir. John Whitney Sr. USA: John Whitney Sr.

- Batchelor, Norman McLaren. Canada: National Film Board of Canada.

- Berlin Horse (1970) [FILM] dir. Malcolm Le Grice. UK: Malcolm Le Grice.

- A Colour Box (1935) [FILM] dir. Len Lye. UK: GPO Film Unit.

- Estuaries 1–3 (2016–2018) [VIDEO] dir. Bret Battey. UK: Bret Battey.

- Five Film Exercises (1941–1944) [FILM] dir. John & James Whitney. USA: John & James Whitney.

- Kisser (2007) [VIDEO] Philip Sanderson. UK: Philip Sanderson.

- Light Music (1975–1977) [FILM] dir. Lis Rhodes. UK: Lis Rhodes.

- Pen Point Percussion (1950) [FILM] dir. Don Peters, Lorne.

- Quadrangle (2005) [VIDEO] dir. Philip Sanderson. UK: Philip Sanderson.

- Rhythmus 21 (1921–1924) [FILM] dir. Hans Richter. Germany: Hans Richter.

- A Rocco Din (2004) [VIDEO] dir. Philip Sanderson. UK: Philip Sanderson.

- Symphonie Diagonale (1921–1924) [FILM] dir. Viking Eggeling. Germany: Viking Eggeling.

- Tracking (2017) [VIDEO] dir. Philip Sanderson. UK: Philip Sanderson.