7

The spaces between gesture, sound and image

Introduction

Emerging from the audiovisual performance practice of the authors, SeenSound has established itself as a regular monthly visual music event in Melbourne, Australia, running formally since 2012. SeenSound has a focus on live, typically improvisational, audiovisual performance, and also showcases a wide range of fixed media visual music works from around the world. As a space for exploring improvisational performance, SeenSound shares common attributes with other long-running experimental music performance events, but is unique in its local context for focusing on audiovisual performance as an integrated practice. It is in the sense of the artists holding to the audiovisual contract of “the elements of sound and image to be participating in one and the same entity or world” (Chion 1994: 222), or of “the primacy of both ear and eye together” (Garro 2012:106), through an “equal and meaningful synthesis” (Lund and Lund 2009: 149) that SeenSound positions itself within the field of visual music, rather than ascribing to the visual centricity of cinema or the audio centrality of (typically electronic dance) music presentations which include projected visuals as an element of the set or decor.

When considered within the broader genre of acousmatic music, a traditionally fixed medium, visual music could be thought of as purely compositional process resulting in another fixed media form for direct playback in a performance space, and not incorporating live performance. While including fixed media visual music works, SeenSound is an event that emphasises live audiovisual performance, and that is the central theme of this discussion.

Live audiovisual performance can take the form of generation and manipulation of integrated audiovisual material, typically by one or more individual performers using a combination of software and electronic or acoustic instruments. Visual material (either fixed or generative) may also be presented with an invitation to performers to improvise in response to the visual material, where the visual material functions as a loose and inspirational score. This approach to reading such a score is based on a high level of engagement with the materiality of the visual elements – the raw perceptual elements of colour, luminance, basic structural elements and temporal variance – not a purely symbolic moving notation of the type seen, for example, in the Decibel Score Player (2019). Naturally enough, there is a spectrum of performance practices that defy neat categorisation. Each individual performance may fall somewhere in between these (and other) modes, and we will explore these in the three performances discussed in this chapter.

As an environment for collective development of audiovisual performance, Seen-Sound focuses on the liminal space between sound and vision as concepts, with an emphasis on exploring the actualities, combinations, co-incidents and collisions of both concept and embodied practice. In this regard, there is a conscious embracing of the complexity of the creative (poietic) and perceptive (aesthesic) processes (Nattiez 1990). For live performances, this complexity arises from both the bespoke nature of individual works, which may be constructed of unique assemblages of software, control interfaces and instruments that embody the work itself, and the unique circumstance of performance with others, where the make-up of the performing ensemble may be unknown beforehand. This degree of idiosyncracy, whether arising from a necessarily idiosyncratic interpretation of a score, or from an idiosyncratic performance system, is likened by Magnusson (2019: 186) to Renaissance music, where composers did not write for specified instruments, and performers were often as much inventors of the piece as they were interpreters.

This looseness in what constitutes an individual piece is at the heart of Seen-Sound’s emphasis on live performance, and we would argue, even at the heart of fixed media renditions of visual music, in that the work itself exists ephemerally in the moment of multi-sensory apprehension by all participants, including the audience. That is, it exists in relationships between subjects, not in the material of any given set of objects. While this may be said of any art form, visual music is in many ways particularly concerned with such relationships: at a literal level, between sound and vision in terms of gestural associations, whether through direct parametric mapping, synchresis (Chion 1994: 63) or looser intuitive associations (Garro 2012: 107). Watkins (2018) and Dannenberg (2005) also address visual music in terms of the creative tension between tight synchronicity of sound and vision on the one hand and complete disconnection on the other, and more broadly, the tension between intention and form, given visual music’s existence as an unstable art form mediated by the constant flux in available technology and cultural influence, interest and practice.

Gesture as an analytical framework for visual music

To gain an insight into the interior spaces of audiovisual performance, we contrast personal reflections on audiovisual composition and performance practice with analysis of three examples of audiovisual performance. There is an inherent tension between the ‘objective’ distance afforded by visual media and the immanence of sonic experience which makes analysis of visual music paradoxical. Voegelin (2010: 15) suggests that sonic experience requires a degree of inter-subjective engagement which is not so obviously required when considering visual media in isolation. Given writing is nothing if not both visual and symbolic, within the context of writing about visual music it is difficult to avoid making the sonic subservient to the visual, and doubly so when attempting to reduce the ephemerality of audiovisual experience to static objects which can be examined.

In this regard, we cautiously seek to complement practitioners’ subjective reflections with an approach to analysis via visualising the ‘trace’ of several audiovisual performances. Visualisations of this kind are not unprecedented in the realm of analysing complex performances: Borgo (2005) uses fractal correlation as a means of examining the features of improvised musical performances by the like of Evan Parker and others, while Jensenius et al. (2010) and Francoise et al. (2012) have developed systems for analysing physical gestures and sound together. It is from this latter work that the motiongram analysis used here arises, although in this case, we apply it to the analysis of the visual component of the works under discussion (i.e. the motion “on screen”), as opposed to the analysis of the movement of dancers or performers conducted by Jensenius et al.

More conceptually, our analysis owes much to Cox’s proposal for a materialist approach to thinking about sound. In approaching not only sound but also visual motion from the perspective of the flux of “forces, intensities and becomings of which it is composed” (Cox 2011: 157), we are interested not in seeking to determine “what it means or represents, but what it does and how it operates”. In addition, the work of O’Callaghan (2017) on multi-sensory perception provides a framework for engaging with audiovisual work that invigorates the intersecting nature of our various modes of perception. In doing so, he specifically addresses the assumption that vision is our dominant mode of perception, drawing upon evidence for non-visual stimuli informing perception equally (or at times even primarily) compared to visual stimuli. In this regard, the juxtaposition of analytical images derived from the auditory and visual domains is intended to reveal some of the underlying gestural similarities and differences which may be at work within a visual music piece as a whole.

To develop this idea further, a multi-sensory approach to understanding visual music need not treat the visual trace as reductive. Rather, it can point to an underlying unification of perception within the body. Key to this perspective is evidence for a close coupling between the cognitive processes for movement and perception. Leman (2008: 77–102) provides extensive discussion of the evidence, including the behavioural observation of infants’ innate ability to perceive gestures and replicate them, and the neurobiological observation that some of the same neurons which are fired to create a gesture (e.g. grasping-with-the-hand) also fire when the subject observes another performing the same action.

By utilising analytical tools which draw directly on the qualities of both sound and motion, our goal is to support a discussion of the inter-subjectivity of abstraction and embodiment that manifests in visual music, particularly looking at the idea of gestural surrogacy. Such an analysis is not intended to present any kind of definitive truth of the way in which visual music functions, but rather is offered as a limited view into the complex flux of forces at work within visual music. While there are many other frameworks for analysing movement and visual aesthetics, for visual music we find Dennis Smalley’s work on spectro-morphology (Smalley 1986, 1997) highly adaptable. Smalley’s typology is laden with physical metaphors and fundamentally uses the concept of gesture as a starting point for looking at sound qualities. It is easy to extend the same analysis to qualities of visual gestures, as much as it is to spectrally moving forms in the auditory domain, giving us a common framework (see also Garro’s phenomenological correspondences in Chapter 1).

At the root level, Smalley considers sound in terms of motions, space, structural functions and behaviours. Motions include both the motion of sounding objects, including such categories as ascent, descent, oscillation, rotation, dilation, contraction, convergence, divergence. He also suggests several characteristic motions including floating, drifting, rising, flowing, pushing or dragging. One can easily imagine these categories being applied to human movement, at either the individual or group level, and by extension the visual morphologies of audiovisual artworks.

When we consider the gestural relationship between sound and vision in visual music, it is useful to look at the way in which Smalley links spectromophological forms of sound art to the morphology of human movement (Smalley 1997), an insight which is backed by the work of Leman. The key idea here is that we make sense of what we see and hear by drawing upon our experience as embodied beings, even though in visual music the experience to which we attend is generally abstracted away from anything immediately recognisable. From a compositional perspective, Smalley identifies several levels of gestural surrogacy, that is, degrees of abstraction away from both the source material and the gestural archetype:

- primal gesture: basic proprioceptive gestural awareness, not linked to music making.

- first order: recognisable audiovisual material subject to recognisable gestural play without instrumentalisation.

- second order: traditional instrumental musical performance.

- third order: where a gesture is inferred or imagined in the music, but both the source material and the specific gesture are uncertain.

- remote: where “source and cause become unknown and unknowable as any human action behind the sound disappears”, but “some vestiges of gesture might still remain”, revealed by “those characteristics of effort and resistance perceived in the trajectory of gesture”.

Building on an awareness of the primal gestural level, first order surrogacy provides simple, immediate accessibility for the interactor, while sustained engagement is generated by providing elements which operate at the higher levels of gestural surrogacy. The aesthesic process is further complicated by the fact that the relationship between gestures which are audibly perceptible versus those which are visually perceptible is not necessarily direct, but exists on a spectrum, as previously discussed. In addition, such gestures may not follow the normal rules of physics in the material world (and in the context of an artwork, it would probably be quite boring if they did).

Outside of visual music, a simple example of such gestural mapping is that of ventriloquism: the puppet’s mouth movements are linked with audible speech events and although we know that puppets don’t speak, perceptually we are still convinced that the sound is coming from its mouth. Despite the novelty of the effect, the congruence of audiovisual stimuli result in what O’Callaghan (2017: 162) argues for as perceptual feature binding: a multi-sensory perception of the same event which may have distinct features such red and rough or bright and loud, but are nonetheless a unified percept. In Smalley’s terms, the ventriloquist’s performance would contain elements of first order gestural surrogacy.

Lower order gestural surrogacy may manifest in visual music through direct parametric mapping between sound and visual elements. For example, the amplitude of a percussive sound being directly linked to the size of a visual element such that repeated patterns of an underlying gesture may result in an experience of auditory and visual pulsing. In this way, the size of the visual object and the amplitude of the sonic object may be perceived to be the result of the same gesture of ‘striking’, even though in our experience of the material world, while percussive instruments may in fact make a louder noise the harder we hit them, visual objects do not routinely become bigger when we hit them.

The same approach could be taken to linking sound elements which may have a floating or gliding quality, for example, with visual elements that also have the same quality of movement. Such a relationship may be parametric, as might be observed via visualisation of audio as a waveform, where a gently undulating tone may have a similar quality to its shape. Or the relationship may be formed through synchresis, that is, simply if two elements appear within the relevant perceptual stream at the same time, without having any explicit parametric mapping at a compositional level.

It can be difficult to distinguish between parametric mapping and synchresis, as the mapping is typically hidden and only inferred (we imagine the ventriloquist is controlling the puppet, but we typically don’t see it explicitly, we only see the puppet’s movements synchronising with audio events). This is the paradoxical challenge of a well-realised mapping process: when the mapping is seamless, the audience assumption can be that events in one sense-modality have just been composed to synchronise with events in the other, rather than having one arise from the other. Live performance can help reduce this effect by demonstrating that multi-sensory events are arising from a common gestural source in the moment, rather than being pre-composed.

In using gestural surrogacy as a tool for analysing visual music, it is important to distinguish between the degree of unification within an audiovisual event (tight versus loose feature-binding) and the degree of gestural surrogacy. If we consider gesture to be a recognisable pattern of experience, in whatever sense-modality, then gestures can be thought of as arising from the features of an event as it unfolds. Tightly bound features, which consistently co-occur or share the same qualities, may be perceived as being the result of first or second order gestures. The more tightly bound a gesture is, the more obvious the relationship between apparent ‘cause’ and ‘effect’, and perhaps thereby, the more obvious the intention behind the gesture. Such an inference arises because of embodied cognition: our experience of physical movement informs our experience of surrogate forms of movement in other ‘bodies’.

Loosely bound features bring uncertainty into the experience of an event: is there a common gesture, a common cause? Are these phenomena even linked? Within such uncertainty, it is harder to recognise the gesture behind them, however that does not mean it is not there. At higher degrees of gestural surrogacy, we may experience less overt, conscious recognition, receiving only hints or vestiges of an underlying pattern. The original gesture may be disrupted or distorted in some way through interruption, amalgamation or elongation, and yet still evoke a response.

At a performance of Jakob Ullmann’s Munzter’s stern by Dafne Vicente-Sandoval, a sparse work which is performed at extremely low volume and requires intent listening from the audience during extended periods of silence, there was a noticeable stirring among the audience just prior to the end of the work, despite no apparent indication that the work was ending. In speaking with Vicente-Sandoval after the performance, she commented that this is almost always the case – the audience knows that the piece is ending, even though it is virtually impossible to recognise it consciously. In writing about her experience of performing the piece, she notes that:

A similar experience of gestural surrogacy arose during the performance of an audiovisual work by Megan Kenny at one edition of SeenSound, in which audio elements from improvised flute and electronics are paired with an almost static visual projection, displaying only the most subtle shifts in hue and saturation across the whole field. Nonetheless, the viewer’s attention is drawn into the visual centre of the work, and being so held, the audio elements exist as figures against a captivating ground. In discussion with Kenny after the performance concluded, it was revealed that there was in fact footage of a face buried behind multiple layers within the visual projection – with only enough of a residual trace remaining to draw the eye as it seeks a feature to latch onto. Thus, the experience of being looked at, even as one looked, became more consciously understood.

To draw together the various threads of this background discussion, we suggest that within visual music, the spectrum of multi-sensory gestural associations arise from, and abstracts our own embodied cognitive processes, and that through examining both the creative intent of the composer/performer and the various gestural traces, however we might obtain them, a deeper understanding emerges. Within this framework of understanding, we present these reflections on three selected performances as an engagement with the intersection of multiple perceptual modes as a space for collaborative art-making beyond the confines of textuality and symbolic representation, with the hope that the reader is inspired to engage more deeply in their own experience of the form.

Wind Sound Breath

Wind Sound Breath is a visual music work by Brigid Burke, performed in this instance by Nunique Quartet (Brigid Burke, Steve Falk, Megan Kenny and Charles MacInnes). This piece utilises densely layered and heavily processed visual material incorporating elements of video footage and graphic elements. In this piece, the visual material is fixed and performances are largely improvised, with certain recognisable elements used to mark sections of the performance.

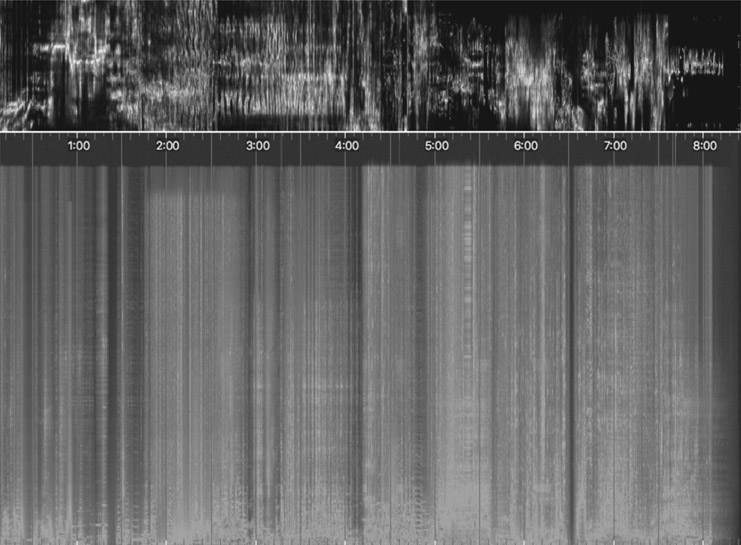

The piece incorporates live and pre-recorded interactive audio electronics, live visual footage and synchronised video for live performance. Thematically, the piece draws inspiration from Yarra Bend Park, the natural bush land near Melbourne Polytechnic. Wind Sound Breath explores connections with the present histories within the campus, Burke’s own musical influences and the importance of the Yarra Bend as an ecological site. In the performance analysed here, live instruments included clarinet, percussion, flute, trombone and live electronics. An overview is given in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 Wind Sound Breath: overview.

Figure 7.2 shows detail of an excerpt between 1:46 and 2:17. Sparse clarinet and flute notes enter in the first 10 seconds, distributed against a background of field recordings of ocean waves and a wood fire. Visually, dense root-like patterns fade in and out with slow pulses of colour, modulated by a rippling visual overlay. The motiongram shows the periodic pulsing of this segment and the spectrogram shows a number of loose correlations between the visual pulse and bands of broadband noise. In this instance, listening to the audiovisual recording reveals this pattern arises from modulations of the volume of the ocean and wood fire recordings and the corresponding modulations of visual material.

Figure 7.2 Wind Sound Breath excerpt 1: detail.

Figure 7.3 shows detail of an excerpt between 3:50 and 4:10. This much more active section features lively figures of trombone, clarinet and flute over timpani, with elements of reversed tape material. Visually the underlying root-like pattern persists, layered with footage of monochromatic lapping water and highly colourised, horizontally scrolling footage of a cityscape. Approximately halfway through the excerpt, the colourised city footage begins to shrink behind the monochromatic water footage. A corresponding drop in activity in the motiongram can be seen from this point. Likewise, activity in the audio performance drops away, with less volume and density compared to the first half.

Figure 7.3 Wind Sound Breath excerpt 2: detail.

From Burke’s perspective as the composer, the aesthetic focus of the work is on exploring relationships between composition, improvisation, visual impact and listening. While pre-composed visual elements are utilised, these are used in improvised video projection performance alongside the improvised audio performance. Audio performers are free to interpret the visual score as it unfolds, and the visual material itself is modified as part of the performance.

In speaking about her process, Brigid Burke explains that concepts for a piece often start with a visual structure in mind, which then drives her to seek out sounds which match that internal visualisation. In terms of actual material, sound always comes first, after which visual elements are created or collected to fit with the audio material. This kind of round trip between an internally visualised concept, sonically realised and followed by a visual realisation, keeps the various elements tightly bound. Burke notes that she’s found if she starts with creating visual material first, the piece tends to lack coherence compared to pieces which have audio as the material foundation.

Visual elements are typically built up from a combination of real-world video footage and heavy processing. Frequently Burke creates paintings and sculptures first and films these works as part of the process. Individual elements are combined in layers to create a dense structure. In processing the material, colour and the underlying pulse of change is an essential expressive element.

For live performance, Burke is frequently manipulating one or more elements of either the audio or visual material in addition to live instrumental performance. Live clarinet performance is combined with either live video mixing or live manipulation of synthetic audio elements. In ensemble performances, the visual element acts in terms of setting the dynamics of instrumental improvisation.

This can be seen in the preceding analysis, with various dynamic changes synchronising across both audio and visual elements. However, the relationship is not just one way, from visual score to audio performance. For Burke, the relationship with other players in the ensemble is of equal weight in terms of shaping the dynamics of her playing and manipulation of either video or audio elements. Thus, while not directly parametric, there is a degree of feedback between audio performance and visual performance which binds the work into a multi-sensory whole.

Perhaps more profoundly, in looking at both the minutiae of audiovisual material within the context of Burke’s creative process, there is a glimpse of the way in which Wind Sound Breath is not representative of any underlying idea, but is thoroughly a manifestation of itself as a complex set of intensities within the material of the visual score, not as an abstract object but as a dynamic field of interpretation, and the players, not as followers of instructions, but as similarly dynamic (i.e. embodied) sites of interpretation of these same intensities.

Shiver and Spine

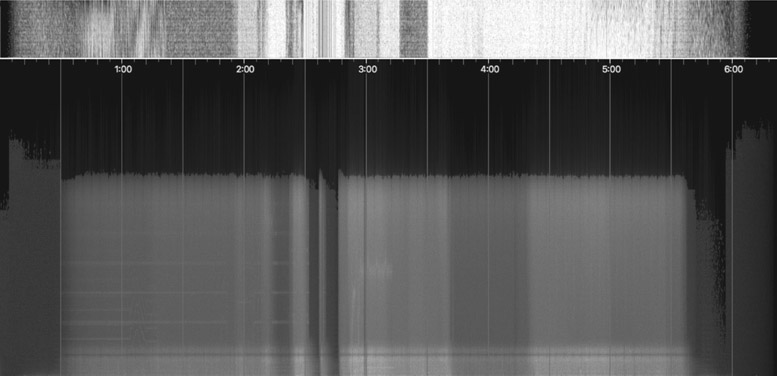

Roger Alsop’s piece Shiver and Spine, for solo guitar and responsive visuals, demonstrates another approach to audiovisual improvisation: one in which visual material arises from the sonic performance, as opposed to improvisations which respond to fixed visual media. A dynamic visual element, depicting the apparent victor of current-to-the-time internal political struggles within the Australian Federal Government, leaps on the screen in response to distorted gestures from an electric guitar. Figure 7.4 shows a still from the performance, while Figure 7.5 provides an analytical overview of the work. This was an overtly political work intended to demonstrate Alsop’s position, which is unusual in the SeenSound context.

Figure 7.4 Shiver and Spine: still.

Figure 7.5 Shiver and Spine: overview.

In the overview, three episodes are marked. Episode A (from 0 to 1:12) introduces the elements of the piece, with video elements distorting in terms of shape, luminance and colour in response to distorted chords and textural scratching from the guitar. During this section, audio and video appear to be tightly synchronised. Episode B (from 1:12 to 2:25) is comparatively sparse, with occasional struck chords left to decay before more gentle tapping of strings is used to re-introduce movement.

Video elements continue to be active during the decay of each chord, calling into question exactly what drives the motion – is it frequency modulation rather than attack, or is there a less direct relationship than had previously been suggested by the performance during episode A? A short section of stronger struck chords introduces episode C (from 2:35 to 3:05), which shows a distinct drop in visual activity in the motiongram with a corresponding sustained block of broadband audio activity in the spectrogram, generated by fierce strumming by Alsop. The responsive visual material is literally saturated by this block of audio input, filling the screen with a red field of colour – an extreme close-up of the piece’s subject.

It is conceivable that without the image of the performer and the guitar in the room, there would be no way to determine if the audio or the visual elements were dominant. In fact, only through a tacit understanding of the technical processes, coupled with the tightly synchronous performance, would the audience determine that the visuals are responding to the audio and not that the performer is responding to the visuals. Like Burke’s Wind Sound Breath, Shiver and Spine does set up a feedback loop between the responsive visuals and the audio performer: at a gestural level, visual response invites audio exploration, and perhaps at the broader discursive level, the sheer repetition of the subject’s image, pushes the audio performer into a moment of sonic rage such as we see in episode C.

Alsop frequently creates works which utilise audio-responsive visual elements, and does so in a way which enfolds the performer and the audience within a recursive loop of stimulus and response. He observes that many interactive audiovisual artworks function to augment human performance, and in this way function as an instrument rather than an interlocutor. In many of his works, rather than create work that unifies or coheres disparate elements, Alsop seeks to interpret human gesture as a different artwork, to be viewed without and separate from the human element involved in its creation. In this regard, he considers it important that when interacting with systems for audiovisual improvisation, performers experience their own actions represented in an unfamiliar way, so that they do not revert to familiar styles or clichés similar to those they may use when interacting with another performers (dancers, musicians).

In Shiver and Spine we see the way in which initial tight correspondences between audio and visual gesture can, through the presence of this kind of feedback loop, generate occasions of rupture where prior relationships begin to break down under the weight of the feedback loop itself, perhaps not unlike the way in which the (too) tight couplings of politics, media commentary and public perception distort the processes of stable government.

Apophenic Transmission (i)

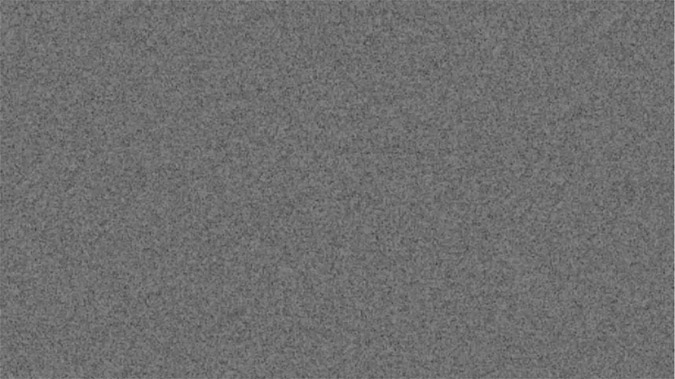

Apophenic Transmission (i) is part of a series of live performance works which interrogate the human tendency toward spontaneous perception of connections and meaning in unrelated phenomena. In part (i), the performer is challenged to seek occasions of apophenia through the use of a somewhat opaque and chaotic control interface, in much the same way as one might attempt to tune a radio or a television set to a dead channel for the purpose of encountering electronic voice phenomena. Both the audio and the visual elements are purely generative, with the audio arising from a software simulation of the Synthi AKS, and the visuals arising from software simulation of analog video synthesiser (Lumen). Part of the purpose of this piece is to call into question the parametric mapping approach to visual music, which Pedersen frequently uses. While the physical performance controls used for both the generative audio and video elements overlap, the performance framework for Apophenic Transmission (i) deliberately confuses this control interface, so that both performer and audience have cause to question whether there is any direct relationship between what is heard and what is seen. As Garro (2012: 106) suggests, “visual music is more than a mapping exercise; the absence of a relationship is itself a relationship”.

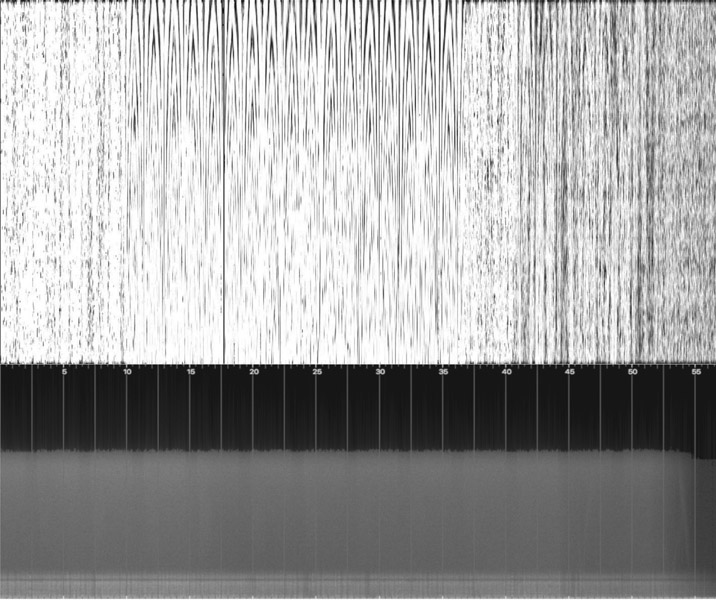

Figure 7.6 gives the spectrogram and motiongram analysis for the whole piece. Compared to the audiovisual analysis of the preceding works, it is no surprise that observable correspondences between sound and vision are hard to extract. Looking more closely at an excerpt from between 1:51 and 2:42, shown in Figure 7.7, we can start to identify features which may trace a common underlying gesture. The motiongram shows several distinct episodes, labelled A–G. In the spectrogram we can see corresponding changes in each of these episodes, although some are more subtle than others. Comparing screenshots from episodes B and D, as shown in Figures 7.8 and 7.9, there is a shift from visual static to a more structured pattern. Dynamically, in episode D the width of the visual bands pulses. There is broadband noise in episode B, which drops away in episode D to reveal beating sine tones, which can be seen as horizontal bands across the spectrogram. These same bands are also faintly apparent in the spectrogram of episode B, but the broadband noise masks them. Episode E exhibits the same qualities as B, and episode F exhibits the same qualities as episode D. Thus the piece starts to establish a gestural link between the presence of audio and visual noise, which masks other underlying patterns.

Figure 7.6 Apophenic Transmission (i): overview.

Figure 7.7 Apophenic Transmission (i) excerpt 1: detail. Figure 7.8 Apophenic Transmission (i) excerpt 1: screenshot from episode B.

Figure 7.9 Apophenic Transmission (i) excerpt 1: screenshot from episode D.

Figure 7.10 shows a segment close to the end of piece. There are fewer distinct episodes compared to the earlier excerpt, as the piece moves toward its conclusion. The audio at this stage is dominated by low sine tones, visible in the spectrogram by relatively higher energy horizontal bands at the bottom. Higher frequently noise still sits across this section, but it decreases in energy across the episode, and is weaker in lower frequency bands between X and Y. Visually we can see a distinct oscillating pattern across the top of the motiongram between 10–40 secs, which corresponds to a pattern of horizontal bands expanding and contracting in a general downward rolling bounce, typical of the classic bouncing ball motion of a modulated low frequency oscillator. The audio spectrogram shows periodic punctuations in the high frequency noise band, which correspond to the lowest point of the visual oscillation (when the horizontal bands are at their widest). The strength of this pattern gradually declines from 35 seconds onward, with lower contrast visually, and a corresponding reduction in high frequency noise content.

Figure 7.10 Apophenic Transmission (i) excerpt 2: detail.

Pedersen notes that for him, performances start “in the body”. His internal feeling is the generative core of each performance, and physical expression of that emotion is typically an essential component. His aim is seeking sounds, or rather transformations of sounds, which match the expressive quality of that internal feeling. In this sense, sound becomes the vehicle for expressing the internal (emotional) state. The range of expression could be very dynamic or very subtle, and the interfaces which support the appropriate range of gestures are a key consideration.

In this regard, a performative aspect to each piece is important, and correlates between gesture and sonic effect are highly desirable. For dynamic pieces, interfaces which allow a range of performative gestures, such as Kinect motion sensors are preferred. Subtle performances are more easily accommodated via traditional knob and slider interfaces. Each system may still need to be learned in terms of gesture mapping. Difficulty in performance is welcomed, as the challenge of various gestures can be part of the desired emotional expression. Likewise, it is sometimes important to not know or understand the mapping. In this case the feeling being sought is one of loss of control/confusion.

This is the case for Apophenic Transmission (i), where the control surface used for performance is mapped into both the audio and visual generation systems, which otherwise are independent from each other. The mapping is deliberately unstable and unrehearsed – leading to accidental, or unintentional correspondences as the performer seeks to understand the affordances of the control surface, both visual and auditory, just as the audience is also seeking to make sense of the system as revealed through the briefly emergent occasions of correlation between sound and image.

Visual music, gesture and affect

To recap on the introduction, in considering visual music, particularly where there is an element of improvisation, the body is a natural starting point for sense making, since as embodied beings, sound cognition is intimately linked with the way our brains also process movement. Yet as habitual meaning makers, bare experience is not sufficient: there is a human tendency to ascribe intent to what we perceive as gestures, however abstract, and connect those gestures with our own personal history and framework for understanding the world. When visual music, as a genre, actively resists narrative, which may be considered the realm of cinema, then what remains is affect – the mood or the feeling, that which is present before narrative emerges, or perhaps that which remains after narrative has been taken away. Furthermore, we are specifically interested in the nexus of audiovisual as a field of affect, as distinct from that which may arise from just a single channel auditory or visual experience.

Let us consider that affect is autonomous of subjective experience, allowing for individual, subjective experience while not denying the existence of a non-subjective reality. Starting with sonic experience, we can consider that sound is likewise autonomous of audition, as a generalisation of the concept of noise being the generative virtual beyond/below perceptual thresholds.

There are several arguments from within sound studies which equate sound and affect. Henriques’s concept of a sonic logos builds upon Lefebvre’s (2004) rhythmanalysis, embracing a broader framework of vibration as not just the means of propagating knowledge and affect, but taking the position that affect is vibration. Affect is carried across varying media, be they electromagnetic, corporeal or socio-cultural, and each of these layers of media manifests the rhythms, amplitudes and timbres of vibrational affect in different ways, be that certain patterns of audible frequencies, pulse rates, muscle contractions, patterns of movement, emotional responses, or cycles of social events, styles or fashions (Henriques 2010). The same vibrational analysis is also found in Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy, which underpins much recent significant theorising of sonic experience, from the work of Steve Goodman (Goodman 2009) to the work of Susanne Langer, as discussed by Priest (2013).

In particular, Scrimshaw (2013) takes up the concept of equating sound, or vibration more generally, and affect, suggesting that sound, like affect, is independent of the subjective experience of audition: just as affection is the subjective experience of affect, and that affect in-itself is that which remains in excess of subjective experience, so too sound in-itself is that which remains in excess of audition. Sound-in-itself in this sense is virtual: real, but not actualised in terms of audition.

This equating of sound and affect generalises Cox’s analysis of noise as the generative field for signal (Cox 2009). The vibrational-materialist approach restores the transcendent to the immanent field of sound by placing the locus of meaning within the relational web of vibrating and listening bodies. Affect finds its meaning in the relational, multi-sensory matrix of repeated patterns, arising from the repetition of a musical phrase, the enactment of ritual, the cycle of seasonal events. This repetition is not the mechanical reproduction that Benjamin (1969) speaks of, let alone the digital replication inherent in current modes of information distribution. Rather it is the repetition of the dawn, which is always new. Henriques quotes Lefebvre:

Turning to the aesthetics of visual experience and affect, the same approach to embodied cognition has been applied to cinema; Rutherford (2003) gives a concise summary, suggesting that “shape, colour, texture, protrusions and flourishes all reach out and draw us to them in an affective resonance”, particularly highlighting the work of Michael Taussig on mimesis, quoting:

With this in mind, and drawing upon O’Callaghan’s argument that perception is truly multi-sensory, it is perhaps useful to consider visual music as being an integrated space of “affective resonance”. Within this mimetic space, it is the quality of the gestures embodied within audiovisual artworks, however abstracted they may be, which evoke engagement with the audience.

Considering the examples analysed here, what affective resonances arise? In Wind Sound Breath there is perhaps a sense of playfulness in the performance as a whole as it shifts between delicate, interlocking filigrees and occasions of robust wrestling. Shiver and Spine is comparatively much more raw, possibly evoking anger or at least frustration in the urgent, distorted guitar, as both performer and audience alike are taunted by a kind of jack-in-the-box visual element. In contrast, Apophenic Transmission (i) evokes a degree of confusion, a tentative, exploratory questioning or doubt about what is being seen and heard. With little that is overt in terms of gesture, the experience is more akin to a half-remembered dream, for both performer and audience.

In reflecting on our experience with hosting SeenSound over more than six years, the experience of liveness that arises from the sharing of gestures in the moment is the compelling reason to continue participating, for creators, performers and audience members alike. If, as Taussig suggests, the act of perception is itself also a gesture, then we are all seeking those moments of contact that arise beyond (or beneath) narrative, in the space between gesture, sound and image.

References

- Benjamin, W. (1969 [1936]) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In: H. Arendt (ed.) Illuminations. New York: Schocken. pp. 217–251.

- Borgo, D. (2005) Sync Or Swarm: Improvising Music in a Complex Age. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Chion, M. (1994) Audi-Vision. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Cox, C. (2009) Sound Art and the Sonic Unconscious. Organised Sound. 14(1). pp. 19–26.

- Cox, C. (2011) Beyond Representation and Signification: Toward a Sonic Materialism. Journal of Visual Culture. 10(2). pp. 145–161.

- Dannenberg, R. (2005) Interactive Visual Music: A Personal Perspective. Computer Music Journal. 29(4). The MIT Press. pp. 25–35.

- Decibel Score Player. (2019) Available online: www.decibelnewmusic.com/decibel-scoreplayer.html. [Last Accessed 11/11/19].

- Francoise, J.; Caramiaux, B.; Bevilacqua, F. (2012) A Hierarchical Approach for the Design of Gesture-to-Sound Mappings. 9th Sound and Music Computing Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark. pp. 233–240. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00847203 [Last Accessed 11/11/19].

- Garro, D. (2012) From Sonic Art to Visual Music: Divergences, Convergences, Intersections. Organised Sound. 17(2). pp. 103–113.

- Goodman, S. (2009) Sonic Warfare. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Henriques, J. (2010) The Vibrations of Affect and Their Propagation on a Night Out on Kingston’s Dancehall Scene. Body and Society. 16(1). pp. 57–89.

- Jensenius, A.R.; Wanderley, M.; Godøy, R.; Leman, M. (2010) Musical Gestures: Concepts and Methods in Research. In: R. Godøy; M. Leman (eds.) Musical Gestures: Sound, Movement, and Meaning. New York: Routledge.

- Lefebvre, H. (2004) Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. Continuum.

- Leman, M. (2008) Embodied Music Cognition and Mediation Technology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Lund, C.; Lund, H. (2017 [2009]) Audio: Visual: On Visual Music and Related Media: Editorial. In: C. Lund; H. Lund (eds.) Lund Audiovisual Writings. Available online: www.lundaudiovisualwritings.org/audio-visual-editorial [Last Accessed 11/11/19].

- Magnusson, T. (2019) Sonic Writing: Technologies of Material, Symbolic, and Signal Inscriptions. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Nattiez, J. (1990) Music and Discourse: Towards a Semiology of Music (trans. C. Abbate). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- O’Callaghan, C. (2017) Beyond Vision: Philosophical Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Priest, E. (2013) Felt as thought (or Musical Abstraction and the Semblance of Affect). In: M. Thompson; I. Biddle (eds.) Sound, Music, Affect: Theorizing Sonic Experience. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Rutherford, A. (2003) Cinema and Embodied Affect. Available online: http://sensesofcinema.com/2003/feature-articles/embodiedaffect/ [Last Accessed 06/07/19].

- Scrimshaw, W. (2013) Non-Cochlear Sound: On Affect and Exteriority. In: M. Thompson; I. Biddle (eds.) Sound, Music, Affect: Theorizing Sonic Experience. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Smalley, D. (1986) Spectro-Morphology and Structuring Processes. In: S. Emmerson (ed.) The Language of Electroacoustic Music. pp. 61–93. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press Ltd.

- Smalley, D. (1997) Spectro-Morphology: Explaining Sound-Shapes. Organised Sound. 2(2). pp. 107–126.

- Taussig, M. (2018) Mimesis and Alterity. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Vicente-Sandoval, D. (2019) On Performing Jakob Ullman. Available online: https://blankforms.org/dafnevicente-sandoval-on-performing-jakob-ullmann [Last Accessed 06/07/19].

- Voegelin, S. (2010) Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Watkins, J. (2018) Composing Visual Music: Visual Music Practice at the Intersection of Technology, Audio-Visual Rhythms and Human Traces. In: Body, Space & Technology. School of Arts, Brunel University. pp. 51–75.