5

Rhythm as the intermediary of audiovisual fusions

Audio + Video = Audiovisual + x

The wish to be able to combine music and the moving image arose long before the technical synchronicity of image and sound in audiovisual media became possible.1 Today we find ourselves in an ‘audio-visual media environment’ and technologically facilitated connections between audio and video are omnipresent.2

The unification of audio and video can be described as a fusion. The term ‘fusion’ emphasises that the result of the medial combination is more than the sum of its parts. In this sense, the combination can’t be described as a simple addition.3 Rather, the result is much more a surplus.4 This increase in value can essentially be linked to the interweaving of our visual and auditory perception. Seeing and hearing are two different sensory modalities which, by mutually influencing each other, become a multi-modal form of perception.5

I suggest analysing the fusion of audio and video on the basis of the model equation A + V = AV + x. Auditory objects (A) and visual objects (V) form audio-visual Gestalts (AV), leaving a remainder (x). This analysis targets the unknown x, which expresses a difference between audio and video (x = A + V – AV). In order to describe x, reference parameters have to be established. They aid in estimating whether the auditory and visual objects to be examined encounter one another congruently or incongruently. If they are congruent we can assume that they make up audiovisual Gestalts (AV) whereas if they are incongruent their distance (x) is increased. In order to establish reference parameters we will use rhythm as a primary audiovisual point of reference.

As an artistic research undertaking, the development and reflection of audiovisual live performances have been used to understand audio and video as rhythmic instruments whose relationship to one another is revealed in their being played together.

I begin this chapter by considering rhythm as a tool of inquiry; this then segues into a discussion of rhythm in my own audiovisual media practice. Following on from this, I define reference parameters and examine several case studies to illustrate and clarify my points. I conclude with some more generalised reflections on audiovisual aesthetics.

Rhythm as an tool of inquiry

The work presented proposes rhythm as a primary criteria for the comparison of audio and video. As a common point of reference it should help in determining reference parameters between the different sensory stimuli.

Rhythm possesses intermodal relationships, addresses all sensory organs and can be seen as a general quality.6 In addition, it can be applied equally to phenomena in time and space.7

Rhythm research is interdisciplinary and its basis is in the exchange between aesthetic disciplines and branches of science and the humanities. Michel Chion refers in his important work Sound on Screen to rhythm’s intermedial competence by conceiving of rhythm as an ‘element of film vocabulary’ which refers to transsensorial perception. Since rhythm is ‘neither specifically auditory nor visual’, it’s well suited as a point of reference by which to set multisensory impressions in relation to one another.8 This makes it possible to use rhythm as an investigative tool for both auditory and visual structures and thus to tackle questions about their fusion. In the words of the ethnographer and philosopher Gregor Bateson, my work pursues ‘a search for similar relationships between different things’ – thereby viewing rhythm as the pattern which connects them.9

Before we can use rhythm as an analytical tool, we have to agree on how the term is to be used. The Greek word ρυϑμσς (rhythmós) refers to the structures of movement as well as to proportion and ratio.10 It suggests no limitation to musical arrangement. The application of the word ‘rhythm’ is inflationary and not limited to a scientific or aesthetic discourse. Cosmological, mathematical, aesthetic and body-related rhythm theories, to name a few, coexist and compete.

Rhythm presupposes a temporal repetition of objects. Once something is recognized as repetition, the temporal or spatial positions can be related to one another. These relations describe a structure and rules can be derived from it. These rules, in turn, determine the degree of the structure’s order.

Structures can be hindered by countless interactions, due to which a given order is subject to continuous variation. This leads to changes in the repetition which can be grasped as movement.

The two states which describe the elementary condition of rhythm are order and movement. The interplay of these contradictory terms obtains a rhythmic quality due to the oscillation of regularity and variance.11

We can assume an objective or a subjective term of rhythm.12 One focuses on the objects of experience, the other on the experiencing subjects.13 It’s important to emphasize that rhythm owes its complexity to the interaction of these aspects. Yet estimating rhythmic efficiency is not the concern of this inquiry; rather, we seek to elaborate concepts of rhythm for audiovisual analysis. This requires, not only a comparison of structures, but a consideration of their mutual influence which can be described as describe as resonance.

Rhythm in audiovisual media

Artistic research unites practical and theoretical analyses. It benefits from a reciprocal interaction between the production and reception of audiovisual artefacts and its basis is the conviction that knowledge is not only expressed with language but also through sensual experience. Artistic work aids thereby in constructing practical experiences from which theoretical knowledge can be derived.

During the course of this enquiry, an extensive body of work was developed. It includes music videos, video art, documentary film, audiovisual live performance, music album and video installations. The aim was to unify and test rhythmic forms in an audiovisual medium. Each of the different medial expressions investigate various fields of audiovisual interplay and aid in elaborating the reference parameters of audio and video.

To this end, the wide field of audiovisual design has to be narrowed through limitations of medium and content. This chapter will concentrate on loop-based music and for video on live-action film footage of body movements.14 The focus on work and dance as filmic sujets suggests itself in terms of rhythm. In addition, the inclusion of my documentary footage from Papua New Guinea refers to the emergence of cultural rhythms through the communal synchronization in work (see Figure 5.1, available online: https://vimeo.com/danielvonruediger/kanubelongkeram).

Figure 5.1 Screenshot from my documentary Kanu belong Keram. Men synchronize with each other by shouting in order to pull a large dugout canoe out of the jungle.

According to Karl Bücher’s thoughts on work and rhythm, physical labour, with its rhythmic sequences of movement, can be seen as a starting point of human artistic expression. Music was cultivated as an auditory expression of rhythmic body movement. Because music and dance depend on the body, they exist in an audiovisual relationship at the beginning of human culture.15 In their connection, dance becomes hearable and music visible. Like dance and music, the moving image enables rhythm to develop in time and space and unite auditory and visual structures.

As a musician, I was particularly concerned with being able to transmit the bodily experience that accompanies making music to the image, and use it for furtherment of knowledge. The performative praxis of the audiovisual live performance enabled me to play audiovisual rhythms.

Experimentation with the manipulation of film projections in real time was already a focus in the Expanded Cinema of the 1960s. The projector was implemented ‘like an instrument’ in order to expand film to encompass a performative level.16 In the video art of the 1970s, trials were undertaken to apply the concept of the auditory synthesizer to the image. The loop established itself both in music and in image montage as the foundation of rhythmic design.17 Technical advancements made it possible by the 1990s to mix moving images live onstage, facilitating the evolution of audiovisual concerts.18 The digital transmission of video signals at the beginning of the 21st century massively reduced the technical effort involved in manipulating moved images live. Today it’s possible, with the help of VJ software, to cut high-resolution video material and add effects in real time. Controlling software with MIDI pads makes editing a similar process to playing drums. Manipulating the moving image has become as instrumental as early light organ players could only dream of.19

Reference parameters

If audio and video are grasped as synchronous, one is lead to make relational assumptions about content as well. The Congruence-Association Model (CAM) describes how structural congruency leads one to assume the existence of a semantic relationship, even in the absence of contextual indications.20

In addition, the Shared Semantic Structural Search Model says that temporal and spatial discrepancies of auditory and visual stimuli are more likely to be tolerated if they possess similar connotative meanings.21 Numerous trials demonstrate the perception of video tracks and soundtracks as unified despite their being asynchronous.22

For this reason, Shin-ichiro Iwamiya divides correspondences of audio and video into formal congruency and semantic congruency.23 Formal congruency refers to the structure of audio and video and addresses synchronicities, whereas semantic congruency describes the correspondence of meaning. Both types are important when analyzing ‘cross-modal interaction of disparate events in auditory and visual domains’.24

In order to discuss these congruencies separately, it makes sense to divide the reference parameters into structural (formal) and semantic parameters. However, before we can examine the structure or the semantics of audiovisual objects, they must be released from the stream of perception. To this end we will need object parameters with which the sensory content of auditory and visual stimuli can be grasped. We borrow the object term from musicology and apply it to visual stimuli.25

In order to estimate the congruencies of audio and video, I suggest therefore a three-way division of the reference parameters into object, structure and semantics.

A three-way division of concretizing perception can already be found in David Hume’s reflections on human understanding. Hume links the possibility of unifying conceptions to the following three principles: similarity, spatiotemporal proximity and causality.26 Hume’s division finds a correlate in the three processes of sensual experience which the Psychological Encyclopaedia calls sensory function, organisation and interpretation.27

These concepts are helpful when concretizing the reference parameters – object, structure and semantics – before we differentiate them further into subcategories.

- Object parameters: Similarity or, respectively, sensory function enables the separation of perception into single, dividable building blocks. They are determined by the relationships of immanent qualities of a stream of perception.

- Structural parameters: The organization or spatiotemporal proximity of objects can be understood as their structure. They are determined by the relationship of objects to a space-time scheme.

- Semantic parameters: The reference to the interpretation which results through causality indicates semantic contents. They are determined by the relationship to personal associations and experiences.

It should be noted that the congruency of the sensory content of auditory and visual objects can only be brought into relation metaphorically. There’s no way, for example, to comparatively measure the brightness of a sound and an image, so such comparisons won’t be considered in the investigation.28 Object characteristics – for example volume, pitch, timbre, brightness and colour – serve purely to distinguish objects. The term ‘object’ refers not only to the construction of new auditive or visual phenomena (e.g. the beginning of a chord or the start of a movement, but to any point of modification of object characteristics (e.g. a pitch alternation when changing from one chord to another or the transition of the direction of a movement). All changes of object characteristics contribute to the marking of an object and therefore to the arrangement of a structure. Changes of object characteristics indicate an apex which is central both for measurements and for our perception. If many object characteristics change, an object becomes particularly obvious. Therefore a cut in video, or a drum stroke breaking the silence, is an especially strong punctuation mark. The more incisive the changes of the object characteristic, the more clearly they define the object’s border. Rhythm can be understood as a structuring of object borders. Because we’re focusing on temporal objects, we can use the musical terms on- and offset to differentiate between a beginning and an end.29 Because so many object characteristics change all the time in music and moving images, determining object borders is in no way unambiguous. It is helpful therefore to reduce the complexity and to examine examples with minimal drum-based music and the act of dancing as the visual object. I collaborated with the dancer Piotr Temps Marciszewski to have him translate structures of different rhythmical electronic instruments in body movements. I used the single choreographies in music to compose not just audio but also the visuals in the music video Dance Instruments (see Figure 5.2, available online: https://vimeo.com/danielvonruediger/danceinstruments). The aim of the experiment was to understand the complexity of auditive and visual objects and how they can be merged in time and space. It became increasingly apparent how different the visual and auditive capacities of detecting object borders were, especially when more structures are brought together. Figure 5.2 Screenshot from my music video Dance Instruments with the dancer Piotr Temps Marciszewski. The musical instruments were transcribed as different body movements by the dancer and connected in space. Source: https://vimeo.com/danielvonruediger/danceinstruments

Besides dance movement the juxtaposition of different work routines – like chopping wood with sawing – led me to separate visual transitions in movement based

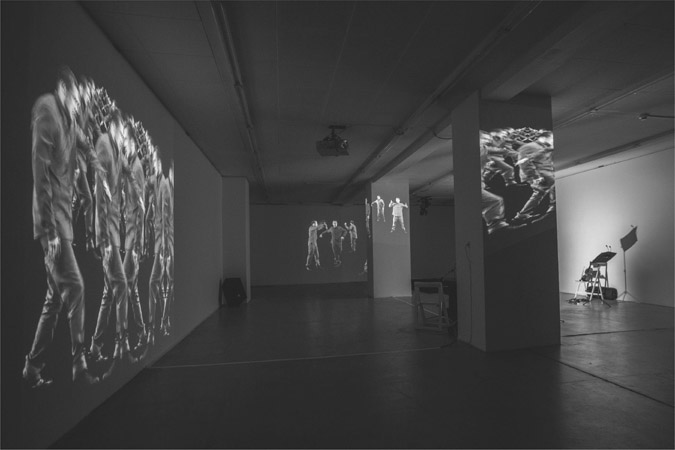

on a change in the direction of movement and the speed of movement. Precise visual objects like a stroke of the axe are defined by the abrupt interruption or reversal of both the direction and the speed of movement. This pointalistic modification of movement accounts for the object’s incisive character. As an accentuated movement, the blow can be contrasted with drawing back, an unaccentuated circular movement.30 Observations of changes to the speed of movement and the direction of movement can organize the visual stream of perception in objects and explain the precision of the object borders. This is helpful for determining relationships between body movements and music. The definition of object borders is a first step towards being able to assess the congruency of auditory and visual objects. If object borders are brought into relation with a grid, the object dimension, or rather its spatial and temporal size, can be determined. This relational grid can be temporal or spatial and its resolution is responsible for the precision of the spatio-temporal structure and its analysis. The expansiveness of an object determines whether it refers to a point in timespace or whether it occupies a spatiotemporal surface. Despite the variety of possible object dimensions, I propose classifying them accross two groups: pointalistic and expansive. Expansive objects fill observable durations of time. Their construction in onset, object body and offset is clearly recognizable. Expansive objects, like sonorous guitar chords or arm movements, can be connected with and transition into each other. In the process, certain object characteristics on their object borders change, (for example the pitch or the direction of movement), while others like timbre or form remain unchanged. In contrast, on- and offset coincide in one sensory impression for pointalistic objects. For example, a video cut or a drum stroke occur so closely that their proximity is below the fusion threshold of both senses alike. Pointalistic objects can’t transition into each other because they need a pause in order to separate themselves from a background. It should be noted here that pauses can also have the status of expansive objects. The dimension of an object is therefore of vital importance for the relationship between form and background. Pointalistic objects require a background from which they can distinguish themselves and appear as figures. Expansive objects fill the background and can be perceived not only as figures but as the background itself. We conclude that it is possible to relate auditory and visual objects to each other based on their object border and their object dimension. Audio and video can equally be categorized as pointalistic or expansive objects, whereby the congruency of this parameter can be altered and analyzed. Registering object borders and object dimension is a prerequisite for the analysis of their structure. When is the central question of a temporal analysis and where that of a spatial analysis. The temporal and spatial organization of objects is mirrored in their structure. A structure describes the position of different objects inside a grid. For a fundamental categorization of the temporal relations between auditory and visual objects, we will refer to Chion’s division of synchronicity into vertical and horizontal relations.31 Thereafter, we can discuss convergences separately, based on points in time and extended periods of time. In the case of a vertical object reference, different objects of the same spatiotemporal point are related to each other simultaneously. In order to create vertical relationships and to relate objects to each other at the same time, their object characteristics have to be assessed as dissimilar. For auditive and visual objects this is a matter of course. We define that the vertical congruency of audio and video in time is derived from synchronicity and in space from convergence. In the case of the spatial congruency of audio and video, the positions of their objects in space must be compared. In discussing space of sound and image, it proved helpful to divide them into x, y and z axes. However, to avoid going beyond the scope of the current investigation, I will concentrate here on temporal concurrence or what we might call synchronicities. Synchronicity is necessarily subject to the imprecision of a measurable or perceivable threshold. Because of differences between an objective and a subjective synchronicity, it makes sense to differentiate them in terms of our investigation of convergences. To achieve technical synchronicity of audio and video, structural grids have to be coordinated with one another. To this end, we must assume a fixed framerate for moving images and a fixed metre with metronomic tempo for music. To interrogate audiovisual synchronicities audiovisual synchronicities, I developed the audiovisual live performance 1Hz by 0101 with the guitarist Stefan Carl (available online: https://vimeo.com/danielvonruediger/1hz0101). By selecting a tempo of 60 BPM and a framerate of 24, all note values, upto 32nd notes, can be technically synchronized with a specific frame.32 This was a prerequisite for creating objective asynchronicities and, in a next step, exposing subjectively perceived synchronicities. Stimuli have to bridge distances in our bodies, which makes stimulus processing itself a complex synchronization problem.33 For audiovisual synchronization, the different speeds of sound and light further complicate matters. In order to compensate these differences, our perception acts to recognizing objects as synchronous which objectively are not. The result is a subjective synchronicity, intensified by an aspiration for Gestalts or harmonious forms.34 Because they appear meaningful to us, our perception is literally intent on prioritizing synchronicities.35 Our tolerance for objective asynchronicity is dependent on the image content and the direction of the sound-image shift. Subjectively, the greatest synchronicity takes effect when sound is played with a one-frame delay at 24 frames per second.36 It became evident that clearly recognizable accents in music and image are essential for an initiation of synchronicity.37 To this end, goal-oriented, accentuated movements like the strike, video cuts and pointalistic sounds are particularly well suited. I investigated the phenomenon of subjective synchronicity with the video installation ein sehen raus hören (see Figure 5.3, available online: https://vimeo.com/danielvonruediger/esinstallation). Since the audio and video tracks were of different lengths, they continuously shifted in relation to each other while looping together. Because the video worked with many quick movements of objects with undetermined borders, many auditory and visual objects were nonetheless perceived as synchronous. Audio and video were perceived as an apparently unified current of stimuli and objects. Figure 5.3 Installation view of the audiovisual installation ein sehen raus hören. The six-channel video work was asynchronously coupled with a passacaglia to examine and reveal subjective synchronicity.

In contrast to vertical references, horizontal object references contain different objects of varying spatiotemporal points, related to each other in succession. Horizontal references can be identified for similar or dissimilar objects. The musical pulse is well suited to analyzing horizontal references. It facilitates the identification of objects within a structure and sets intuitive temporal positions. The affiliation of single objects with a beat, results from their position and their emphasis. In addition to emphasis, the rhythmic structure is also responsible for the arrangement of objects.38 To comprehend an extra-sensory arrangement, we can refer to further factors of Gestalt theory. In particular the principles of proximity, similarity and common movement, which are essential for the assignment to a group.39 The metre indicated by the musical beat is central for the transposition of a musical movement to a body movement. Let us explore these movements which result from structure in more detail, as independent structural parameters. The effect of rhythm can be attributed to movement transfer. Its basis is the idea of comparing body movement and musical motricity.40 The so-called phi-phenomenon says that even two spatially removed blinking points can be perceived as one moving point.41 In this sense, the repetition of an object becomes a movement through time. The prediction of structural movement expresses itself via the fact that future objects can be anticipated. When the direction of a movement is predictable, we assume its continuation. For example, an object which moves through an image anticipates the moment of its disappearance from the frame. Musical movements demonstrate this in the same fashion, for example with the continuation of an expected beat. By breaking the beat, and with it our anticipation, the unfulfilled expectations become obvious. When it’s oriented on music, dance can be understood as a visualization of musical movements. Performative investigations of visualization for a passacaglia, juxtaposes musical and visual movements and pursues their congruencies. The choreography works with different articulations of the repeating and varying musical structure. Manipulating the video image enables fixing a movement in two dimensions and thereby making traces of movement visible (see Figure 5.4). The aim was

to compare possibilities of expressing movement in sound and image, as well as in time and space. Figure 5.4

Performance in cooperation with Malwina Sosnowski based on the visualization of a passacaglia for solo violin in G-minor (1674) by the composer Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber. Live capture makes it possible to fix the motions of her playing and walking in space and to combine them with her musical movements. We establish that auditory and visual objects are congruent when they are part of a common structural movement and evoke similar anticipations.42 Put another way expectation, as a common reference point, unites dissimilar objects in a common movement. A movement is the expression of a change which can only be experienced in time. The timespan necessary for this change determines its tempo. To bring tempo into relation in audio and video, we have to compare how it can be captured in each medium. In turn, we can develop systematics to relate BPM (beats per minute) to FPS (frames per second). If two structures orient themselves on the same grid and if its objects are synchronous, the structures have the same tempo. However, it’s entirely possible for isochrone structures to have the same tempo too. For the juxtaposition of auditory and visual tempi, both must be grasped separately and then compared to each other to define them as congruent or incongruent. We summarize that beat structures and their metre, the appearance of common movement, as well as the tempo, can be used to examine the horizontal congruency of auditory and visual objects. Whereas structure refers to spatiotemporal organization, semantics refer to the interpretation of meanings. Focusing on structure lends itself to an analysis of rhythm. Yet, investigations of audiovisual perception demonstrate that semantics are also important for relating auditory and visual sensory modalities to one another. Structure and semantics go hand in hand in the development of audiovisual Gestalts. A structural incongruency can be compensated by semantic congruency, and a semantic incongruency by structural congruency. The use of documentary materials for my musical visualization showed that structure and semantics relate antagonistically in regards to attention. One gains attention at the loss of the other. In order to counteract this antagonism, music visualizations usually resort to abstract depictions. They possess a lower semantic intensity and distract less from the structure. I established the performance duo 0101 (www.0101.wtf) to investigate possibilities for decreasing the semantic intensity of video footage, for example by altering the visual material to be its negative (see Figure 5.5). Figure 5.5 The semantic intensity of the video footage from Papua New Guinea is decreased by various techniques, for example altering the visual material to be its negative and projecting on a plastic screen. It’s not easy to classify the concreteness or abstractness and therefore the semantic level of a visual or auditory object. I propose using the technical reversal of the direction of playback to divide the semantic value into three levels, undefined, defined and deliberate.

In addition to the direction of action, there is the potential to develop other parameters to investigate the semantic congruency of audio and video.43 However, the current deficiencies with regard to semantic parameters needn’t prevent us from summarizing the reference parameters developed so far, reaching towards a definition of x.

Object parameters

Object characteristic

Object border

Object dimension

Structural parameters

Vertical relations

Synchronicity

Horizontal relations

Beat/metre

Anticipatable movement

Tempo

Semantic parameters

![]()

Conclusion: X =

We recall that x = A + V – AV (x = Audio + Video – Audiovisual).

Over the course of my inquiry it has been possible to develop reference parameters, which aid in formulating a statement on the congruency of audio and video. By delving into an analysis of x, I have offered an incentive to further develop, change, criticize, dismiss, extend, rename, confirm and above all to use the parameters developed. I would be greatly pleased if x was further reflected upon and the implied questions of intermediality confronted by my fellow practitioners.

The development of three main and numerous subreference parameters is a first step to determine x. They can be collected as shown in Table 5.1.

| Object Parameters | Object characteristic | ||

| Object border | |||

| Object dimension | |||

| Structural Parameters | Vertical Relations | Synchronicity | Objective |

| Subjective | |||

| Convergence | x axis | ||

| y axis | |||

| z axis | |||

| Horizontal Relations | Beat/Metre | ||

| Anticipatable movement | |||

| Tempo | |||

| Semantic Parameters | Direction of action | undefined | |

| defined | |||

| deliberate |

It becomes apparent that x is a subjective estimation which can’t be determined absolutely. The value (x) exists in relation to evolving audiovisual Gestalts (AV). When the previously listed parameters prove to be incongruent in audio and in video, this curbs the development of audiovisual Gestalts and increases the value of x. The relation of x to AV can be simply described in two ways.

- x < AV

- x > AV

For I the Gestalt character of auditory and visual objects is predominant and the distance between audio and video is minimal. An audiovisual fusion with x < AV can be described as consonant.

For II the deviation of the auditory and visual objects is predominant and the distance between audio and video is large. An audiovisual fusion with x < AV can be described as dissonant.

From a particular value of x upwards, the moving image falls into two separate sound and image tracks. To borrow a phrase from Chion, one can speak of a ‘hollowing-out’ effect. With an obvious x, auditory and visual perception can be ‘divided one by the other instead of mutually compounded’. This quotient can lead to ‘another form of reality, of combination, emerged’.44

The acceptance of structural and semantic discrepancies is subjective and context-dependent. Thus an obvious asynchronicity can be praised as avant-garde and grasped as meaningful in an art film, while regarded as irritating in a feature film. Expectations of and tolerance towards structural and semantic discrepancy are both largely dependent on their framing.

This should serve as an incentive to use x as a formal element and to work consciously with the distances between audio and video. A variable x in one audiovisual media can provoke an undulation between auditory and visual attention and evoke audiovisual tension.

Furthermore, x should advance media-theoretical investigations. In Danto’s terms, x can be used for the assessment of audiovisual fusion as pure representation or as an artwork. A pure representation aims at a state of pure transparency in relation to its medium.45 An artwork on the other hand indicates the medium and is in this sense opaque. X as a factor of representation is responsible for the opacity of a work, whereby x becomes a variable of expression and can help a representation to become art.46 This function depends on whether the implementation of x occurs consciously and whether x is used to express something. In that x expresses something about the content of a work, x itself can be become an expression.47

The audiovisual investigation closes there with the expressed aim of contributing to the philosophical debate examining the relationship between art and reality.

In the end it is the medium which separates reality from art.48

References

- Alexander, A. (2015) Audiovisual Live Performance. In: See This Sound: Audiovisuology a Reader. Köln: Buchhandlung Walther König. pp. 198–211.

- Bakels, J.-H. (2017) Audiovisuelle Rhythmen: Filmmusik, Bewegungskomposition und die dynamische Affizierung des Zuschauers. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Bateson, G. (1995) Geist und Natur: eine notwendige Einheit (Vol. 4). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Bergman, A.S. (1990) Auditory Scene Analysis: The Perceptual Organization of Sound. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Boltz, M.; Schulkind, K. (1991) Effects of Background Music on the Remembering of Filmed Events. Memory and Cognition. 19 (o. J.). pp. 593–606.

- Buchwald, D. (2010) Gestalt. In: Ästhetische Grundbegriffe. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler. pp. 820–862.

- Chion, M. (1994) Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Chion, M. (2009) Guide to Sound Objects. London. Available online: https://monoskop.org/images/0/01/Chion_Michel_Guide_To_Sound_Objects_Pierre_Schaeffer_and_Musical_Research.pdf.

- Chion, M. (2012) Audio-Vision. Ton und Bild im Kino. Berlin: Schiele und Schön.

- Cohen, A.J. (2013) Congruence-Association Model of Music and Multimedia: Origin and Evolution. In: The Psychology of Music in Multimedia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 17–47.

- Daniels, D.; Naumann, S. (2015) Introduction. In: See This Sound: Audiovisuology a Reader. Köln: Buchhandlung Walther König. pp. 5–16.

- Danto, A.C. (1984) Die Verklärung des Gewöhnlichen. Eine Philosophie der Kunst. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Danto, A.C. (2014) What Art Is. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Fitzek, H. (1996) Gestaltpsychologie. Geschichte und Praxis. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Grüny, C.; Nanni, M. (2014) Rhythmus – Balance – Metrum. Formen raumzeitlicher Organisation in den Künsten. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Hegel, G.W.F. (1992) Vorlesung über die Ästhetik I. Hegel in 20 Bänden: Auf der Grundlage der Werke von 1823–1845 13. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Heide, B.L.; Maempel, H.-J. (2010) Die Wahrnehmung audiovisueller Synchronität in elektronischen Medien. Tonmeistertagung – VDT International Convention. 26. pp. 525–537.

- Hume, D. (2017) Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. Jonathan Bennett. Available online: www.earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/hume1748.pdf.

- Iwamiya, S.-I. (2013) Perceived Congruence between Auditory and Visual Elements in Multimedia. In: The Psychology of Music in Multimedia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 141–164.

- Kassung, C. (2005) Der diskrete Takt des Menschen. In: Anthropometrie. Zur Vorgeschichte des Menschen nach Maß. München: Wilhelm Fink. pp. 257–275.

- La Motte-Haber, H. de (2013) Klangkunst im intermedialen Wahrnehmungsprozess. In: Wahrnehmung – Erkenntnis – Vermittlung. Musikwissenschaftliche Brückenschläge. Hildesheim: Georg Olms. pp. 32–40.

- Lange, E.B. (2005) Musikpsychologische Forschung im Kontext Allgemeinpsychologischer Gedächtnismodelle. In: Musikpsychologie. Laaber: Laaber. pp. 74–100.

- Möckel, W. (1998) Warhnehmung. In: Psychologische Grundbergriffe. Hamburg: rowohlts enzyklopädie. pp. 681–683.

- Müller, A. (2015) Das Muster, das verbindet. Gregory Batesons Geist und Natur. In: Schlüsselwerke des Konstruktivismus. Wiesbaden: Springer. pp. 113–127.

- Ruccius, A. (2014) Musikvdeo als audiovisuelle Synergie. Michel Gondrys Star Guitar für the Chemical Brothers. In: Bildwelten des Wissens Bild – Ton – Rhythmus. Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. pp. 98–106.

- Schlemmer-James, M. (2005) Schnittmuster: Affektive Reaktionen auf variierte Bildschnitte bei Musikvideos. Technische Universität.

- Schmitt, A. (2001) Der kunstübergreifende Vergleich. Theoretische Reflexionen ausgehen von Picasso und Strawinsky. Würzburg: Verlag Königshausen & Neumann GmbH.

- Scholl, B.; Gao, X.; Wehr, M. (2010) Nonoverlapping Sets of Synapses Drive on Responses and Off Responses in Auditory Cortex. Neuron. 65(3). pp. 412–421.

- Spitzer, M. (2002) Musik im Kopf. Hören, Musizieren, Verstehen und Erleben im neuronalen Netzwerk. Stuttgart: Schattauer.

- Spitznagel, A. (2000) Geschichte der psychologischen Rhythmusforschung. In: Rhythmus. Ein inter-disziplinäres Handbuch. Psychologie Handbuch. Bern: Hans Huber. pp. 1–41.

- Stein, B.E.; Meredith, M.A. (1993) The Merging of the Senses. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Stöhr, F. (2016) endlos. Zur Geschichte des Film- und Videoloops im Zusammenspiel von Technik, Kunst und Ausstellung. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Warren-Hill, S.; Coldcut. (1996) Natural Rhythm (Natural Rhythms Trilogy Part II) (Coldcut). Musikvideo.

- Woitas, M. (2007) Immanente Choreographie oder Warum man zu Strawinskys Musik tanzen muss. In: Die Beziehung von Musik und Choreographie im Ballett. Berlin: Vorwerk 8. 219–232.

- Wundt, W. (1911) Grundriss der Psychologie. Zehnte Auflage. Leipzig: Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann.