22

Sound – [object] – dance

A holistic approach to interdisciplinary composition

Introduction

The origins of interactive dance can be traced back to John Cage and Merce Cunningham’s collaboration Variations V of 1965, yet vigorous research on developing wearable or camera-based motion-tracking sensors has only been conducted by a larger number of composers since the 1990s. As a consequence, debates and criticisms regarding the usage of technology in the dance technology community have been directed towards artists who were “eager to work with newly arising digital tools”, but who had “little understanding of the inner workings of electronics or computer code”, which in turn created trivial works (Salter 2010: 263–264). This is a critical point of view; however, I find it not entirely fair towards the artists. The increasing accessibility of Max/MSP,1 with its graphical interface, and user-friendly tools like Isadora2 have attracted composers and artists who are new to programming, enabling them to create interactive artworks. These are creative users who are not necessarily software developers. I argue that the problem is not lack of knowledge of the technology, but a lack of investigation into novel mediums that the artists did not primarily practice within. A more appropriate critical question asked by Chris Salter is how could the use of motion-tracking technology “enlarge dance as a historical and cultural practice” and what kind of aesthetic impact could it have on spectators who were not privy to the process of mapping movement data to the resulting media? (2010: 263).

In gesture-driven music, when interactivity is considered a crucial element that has to be demonstrated to the audience, it can easily restrict interactive dance to the folly of mere demonstrations of technology. Thus, it results in trivial works. Scott deLahunta (2001) argues that in the field of computer music the process of new musical instrument learning has been assumed to be a form of dance training. Julie Wilson-Bokowiec and Mark Alexander Bokowiec (2006: 48) point out that mapping sound to bodily movement has been described in utilitarian terms, that is, “what the technology is doing and not what the body is experiencing”. According to Johannes Birringer (2008: 119), developing interactive systems with this utilitarian perspective requires performers to learn “specific physical techniques to play the instruments” of the outcome media. Dancers find it hard to think of these as they do the “intuitive vocabulary” that they have gained through their physical and kinaesthetic practice. Discussions about creating musical instruments are still valuable to the development of interactive systems. However, I find that this narrow focus on the gestural or postural articulation of technology misses the aesthetic concerns in creating choreography with dancers.

To direct and frame my own compositional practice, I have shaped the following research questions: (1) How can interactive systems guide collaboration by encouraging dancers to use their intuitive vocabulary, not just demand that they learn the technological and musical functions of the interface? (2) Once I have considered the sounds to be used in a piece, how should I direct dancers to create choreography as well as sound composition with my interactive system? To answer the first question, it was necessary to investigate the choreographic composition process. To answer the second question, I applied the interactive technology in collaboration with my dancers. In the following sections, I will elaborate this compositional process developed with my collaborating dancers and applied in two works Locus and The Music Room. For this particular research, I decided to work with professionally trained contemporary dancers; as my contextualisation is strictly based on contemporary dance technique.

Physical restriction as a core choreographic method

“Choreography has gone viral”, argues Susan Leigh Foster (2010: 32). She writes that since the mid-2000s the word has been used as “general referent for any structuring of movement, not necessarily the movement of human beings”. The word “choreographic” has been used to describe the process of paintings, sculptures and installations, such as Allan Kaprow’s movement score 18 Happenings in 6 parts and Bruce Nauman’s Green Light Corridor. These works were focused on certain movements of the artists or viewers, and were, therefore, choreographed. More recently, the artist Ruairi Glynn presented his kinetic sculpture Fearful Symmetry as a choreographic idea at the conference Moving Matter(s): On Code, Choreography and Dance Data in 2017. The reason this kind of movement from non-dancers and non-human movement has come to be recognised as “choreographic” is because dance has changed dramatically since the mid-twentieth century to eliminate virtuosic movements. For example, the Judson Dance Theater choreographers deliberately incorporated everyday movements such as walking, running and sitting into their work (Au 2002: 161, 168). In his essay Notes on Music and Dance, Steve Reich (1973: 41) writes that the Judson group choreographers have embraced “any movement as dance”, equivalent to John Cage’s idea that “any sound is music”.

Yet, for my collaboration with dancers, I thought it more appropriate to understand how choreographers think of choreographic movement rather than what choreography ultimately is. Movement art pioneer Rudolf Laban sees choreography as a “continuous flux” of movement that should be understood alongside both “the preceding and the following phases” (Ullmann 2011: 4). Laban’s dance notation shows movement “trace-forms” through directional symbols inside the kinesphere3 rather than specific postures. This inspired me to think about what principally stimulates which movement.

I found the contemporary dance choreographer William Forsythe’s composition approach interesting because he extended Laban’s notion of the kinesphere. In his lecture video Improvisation Technologies, Forsythe demonstrates possible movement variations depending on a newly given axis without stepping away from the first position; the axis of movement is no longer the centre of the body. For instance, he shows as a normal scale of the kinesphere the entire body in a cubic space, and then creates a smaller scale to isolate his left arm to make arm movement variation. Furthermore, Forsythe asks his dancers to imagine objects or geometric lines to create movement with or around, which he calls “choreographic objects” (Forsythe n.d.). Re-orientating physical perception with these imaginary spaces and objects is Forsythe’s core movement creation technique. Forsythe provides inputs at “the beginning of a movement rather than on the end” and “in the process, discover[s] new ways of moving” (Forsythe and Kaiser 1999). Similar to Forsythe, choreographer Wayne McGregor proposes that his dancers imagine an object as well as use other sensations such as colour or music to compose choreography. Another technique McGregor uses is to provide dancers with a physical problem that they have to solve through movement. For example, dancers are asked to “picture a rod connected to their shoulder, which is then pushed or pulled by a partner some distance away” (Clark and Ando 2014: 187). McGregor describes these ways of creating movement phrases with specific physical conditions as a “physical thinking process” (McGregor 2012).

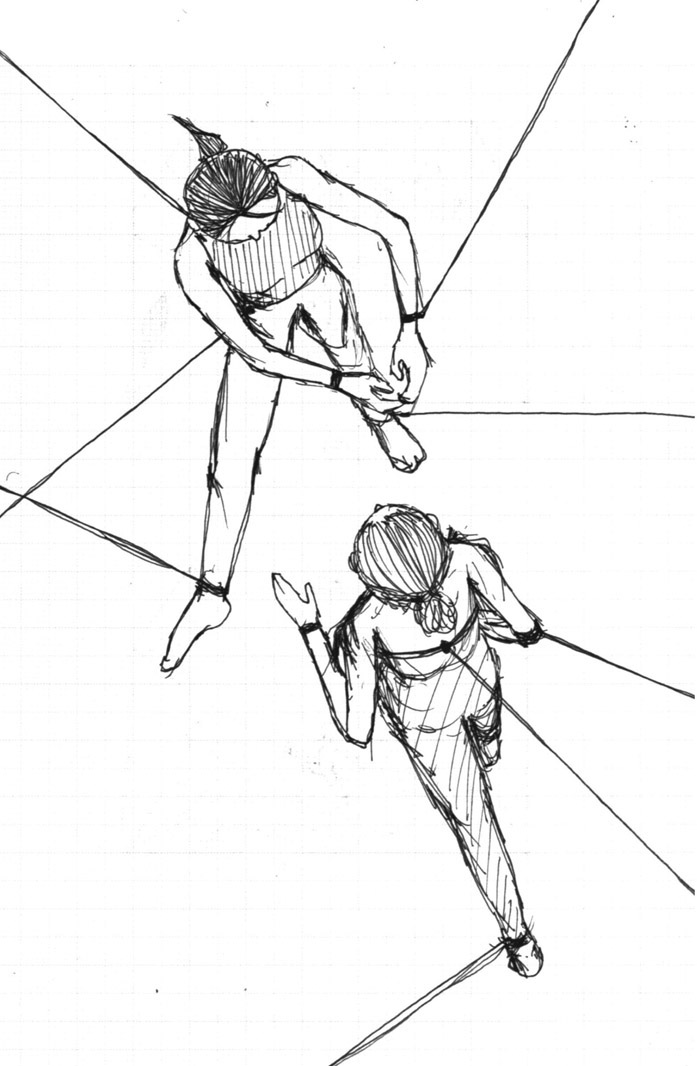

What is interesting from both Forsythe and McGregor’s methods is that rather than freely improvising to seek new movement they restrict their physical condition with imagined objects and space. In order to actively stimulate and engage dancers to create choreography with the interactive system, I decided instead to provide a visible and tactile motion-sensing device that primarily challenged performers to dance, and to let these movements create the sounding results. Subverting common conventions in which motion-tracking or motion-sensing devices are applied as a mere interface for preserving the freedom of the dancer’s movement – connecting the presupposed musicality of movement data to the output – I decided to replace the mental imagery described by Forsythe and McGregor with actual physical restriction using the cables of the Gametrak controllers (Figure 22.1). In this way, the Gametrak provides a technological restriction that governs my sound composition and movement creation as both an interface and a physical limitation that has to be accounted for by the dancers.

Figure 22.1 Sketch of two dancers tethered with the cables of the Gametrak controllers.

Amongst interactive musical instrument and dance collaborations, I find the work Eidos: Telos (1995) by Forsythe and the Studio for Electro-Instrumental Music (STEIM) composer Joel Ryan the most interesting, even though it was developed in the 1990s, at the very beginning of the period of experimentation in interactive musical synthesis with computers. Across the stage, a net of massive steel cables was set to be amplified by contact microphones and in turn become a large-scale sonic instrument when plucked by the dancers. The choreography was composed around the steel cables; there was a moment when one dancer danced in front of the steel cables and a group of dancers danced behind the cables in lines. The stage lighting was set to become dimmer when the dancers stood behind the cables. Later, a dancer in a black costume held a panel and scratched the cables while moving to the left and right sides of the stage. The instrument was “audio scenography: the replacement of visual scenography with a continually transforming audio landscape” and showed “the shifting of dance music composition in Forsythe’s work towards the design of total acoustic environments” (Spier 2011: 57–58). The instrument created simple and modern-looking scenography without superfluous technological aesthetic – which Forsythe usually seeks in his other works – and acted as the work’s core compositional as well as dramaturgical strategy. Similarly, I wanted to include the symmetrical lines created by the cables of Gametrak controllers as part of visual scenery as well as to provoke dramaturgy. But in my works the cables were connected to my dancers’ bodies, which affected their ways of moving more intimately.

Locus

While searching for case studies in dance and technology collaboration, I found that McGregor worked with cognitive scientists to seek connections between creativity, choreography and the scientific study of movement and the mind (deLahunta 2006). The scientists observed how McGregor and his dancers developed choreography from mental imageries and helped break the dancers’ movement habits by shifting the perspectives by which these imageries were approached. What interested me about this collaboration was that the choreography itself came about as the result of technological adaptation rather than a representational event such as a sound or image created with real-time movement data. One outcome to the collaboration was the choreographic composition tool Mind and Movement for choreographers and teachers, which includes image cards with related movement tasks to stimulate developing and structuring movement materials.

Inspired by the use of imagery for choreographic composition, I decided to include a real-time video composition that could be used as choreographic stimulus. The result is my composition Locus4 based on three photographs I took in Manchester city centre (Figure 22.2). They were chosen because my main collaborating dancer Katerina Foti was interested in creating choreography inspired by the geometric shapes and lines in these architectures. I decided to place eight hacked Gametrak controllers in a cube shape – four above and four below – as shown in Figure 22.3, and locate the dancers in the middle so that the Gametrak cables could also create geometric lines when they were connected to the dancers’ bodies.

Figure 22.2 Three photographs used for Locus.

Figure 22.3 Live performance of Locus at Electric Spring Festival 2016 in Huddersfield. Dance artist: Natasha Pandermali.

Source: Jean François Laporte, Electric Spring 2016, © University of Huddersfield.

I proposed using the Gametrak controllers as a visual stimulus and physical restriction to Foti and as she was aware of Forsythe’s approach she was interested in the method. This was my first time composing an interactive music with physical restriction, and I decided to apply a methodology of improvisation to find the most suitable compositional approach. To begin the collaboration, I devised the interactive audiovisual work in three different parts. I fixed the overall framework of the piece but left the inner structures to be completed by the dancers. Different choreographic tasks were set for each part, and each part was constructed as the dancers executed the tasks.

The tasks indicated what to do with the Gametrak controller, as well as the duration and speed of movement, but the detailed body movements in response to these tasks were up to the dancers. For instance, the first part of the composition consists of three different audiovisual variations.

- The first variation:

- Tether the cables one by one slowly (total four each).

- Continue this act until you hear the sound of ‘gong’ thirty times so that the next part starts.

- The second variation:

- Improvise as duet for 2 minutes.

- Explore the movable space between and around each other’s body.

- The third variation:

- Perform as solo for 1 minute each.

- When the solo is finished, move to the side and detach three cables.

I did not aim to deliver a specific storyline with my audiovisual work, but I let the given materials be processed through my real-time synthesis engine so as to see what would be evoked during the composition process with the dancers.

To interrogate the use of the Gametrak controllers and the choreographic tasks with my collaborating dancers, I planned several steps to guide Foti and another dancer, Natasha Pandermali, towards gradually constructing a choreographic composition with my interactive sound synthesis before I revealed the specific choreographic tasks for each part of the composition. First, I asked the two dancers to tether four cables each to their bodies and to improvise to find out how to move within the restrictive conditions without any audiovisual work. Once they had got used to moving within the conditions, I then provided more specific choreographic tasks section by section depending on the structure of the audiovisual composition. During this process, the dancers proposed how they would create choreography with my movement tasks and I selected promising materials. We repeated the proposing, selecting and modifying process several times until we completed the composition.5

Such an approach of proposing and selecting choreographic materials is a common in contemporary dance, as exemplified by the choreographers Forsythe and McGregor. While searching for the origin of this choreographic method, I found that some contemporary dance choreographers began using the so-called problem-solving concept in the 1960s as research in information theory and artificial intelligence awakened around that time (Rosenberg 2017: 185–186). This technique adopted improvisation as a choreographic compositional method. For example, the Judson Church group choreographer Trisha Brown “cast her dancers into what problem-solving theorists call a ‘problem space’ defined by an ‘initial state, a goal state, and a set of operators that can be applied that will move the solver from one state to another’” (Rosenberg 2017: 186). This algorithmic process is also apparent in Forsythe’s choreographic procedure Alphabet (Forsythe and Kaiser 1999) and McGregor’s “if, then, if, then” process (McGregor 2012).

I also find similar algorithmic thinking in the electroacoustic composer Simon Emmerson’s model of compositional process. Since electroacoustic music does not use traditional musical notation systems and materials, Emmerson (1989) proposes a new compositional model for contemporary music. The model consists of a cycle of actions: the composer does an action drawn from an action repertoire, which then has to be tested. After testing, accepted materials reinforce the action repertoire and rejected ones can be modified for the action or removed. Emmerson explains that research begins when one “tests” the action, and new actions need to be fed into the action repertoire to evolve the research further (Emmerson 1989: 136). Similarly, in my composition process I provide new actions with the Gametrak controllers, and my collaborating dancers “test” the actions and reflect on the next phase.

The reason that I decided to provoke the dancers to improvise with this special condition was to encourage them to resist their habitual movements. This is my method for employing directed improvisation, using a problem-solving technique as a compositional strategy, as well as to discover new ways of moving. Notoriously, Cunningham rejected improvisation because he resisted his instinctive preferences in order to create more innovative choreography (Copeland 2004: 80). However, I did not want to eliminate intuitive decisions from my dancers. My intention was to let the dancers contribute their movement knowledge and skills to the choreography beyond their own habits. In other words, this was my way of provoking a “physical thinking process” as McGregor (2012) calls it. The resulting movements would be what had been processed through the dancers’ movement repertoire with my new inputs. Eventually, a composition is completed with multiple iterations of these actions.

After the first rehearsal of Locus, I interviewed Foti and Pandermali to ask about their experience working with my method. Foti mentioned that the tethered controllers limited her but also made her create movement because of the restrictions. Pandermali agreed and explained further about the restrictions: “We may put some restrictions to ourselves [when we dance], but it is like more mental. […] But this time we were physically restricted […] it is more […] true. The movement comes from what we are allowed to do with the cables. […] Now [the restriction] was strict, but at the same time, there was a completely new world to explore.” I also found that the dancers were able to realise how they moved by listening to the sounds they created, and that also affected how they moved between themselves (Foti and Pandermali 2015).

My audiovisual work and choreographic tasks were neutral in terms of directing any narrative or emotions. I used abstract forms because I wanted the dancers to freely interpret and express the audiovisual work through their own movements. After creating Locus, I searched for other choreographic works that used abstraction so as to better reflect and understand my own method, and found works by the choreographer Alwin Nikolais. I found his compositional approach, which is often called “total theatre”, very similar to mine. His focus is on creating interdisciplinary work using motion, light, sound and colour, rather than creating only movement phrases. His abstract dance performances have sometimes been accused of “neglecting the element of drama”, but Nikolais has insisted that “abstraction does not eliminate emotion” (Au 2002: 160). His intention was to get away from storytelling, which was common in early modern dance. Instead, he has focused on motion as he believed that “motion is the art of dance” just as “sound is the art of music” (Nikolais 1974). He also used abstract electronic music because he thought instrumental music would activate another sense association with the performer of the instrument rather than only its sound (Nikolais 1974). The same kind of abstraction was adapted to dancers: Nikolais encouraged his dancers to use their minds rather than try to play a role. For instance, in his work Tower the dancers construct a tower by stepping on or hanging onto a metal structure without a storyline, “yet their motion helps build images that are fraught with emotional connotations” (Au 2002: 160).

Similarly, during the composition process of Locus, my collaborating dancers naturally developed a drama between themselves and the restrictive performance environment as they improvised more and more. When Pandermali was tethered with eight cables in the last part of the composition, for example, I suggested tethering one of the cables to her neck rather than to her limbs so as to increase the challenge for her (Figure 22.3). For this part, I made the cube images change their textures randomly with the three photographs and the interactive audiovisual synthesis was disabled. The non-controllable audiovisual set and Foti’s contrasting free and fast movements provoked Pandermali to express struggle with her movement within the extremely restrictive conditions compared to other parts of the composition. Also, Pandermali confessed to me that she sometimes made more of a struggling gesture than the actual physical situation demanded. Foti explained that although the choreographic task was functional, the dramaturgy could evolve by way of the restrictions not letting them move in familiar ways. “By searching the unfamiliarity, we ended up having our own special vocabulary for our movement which connoted an untold story” (Foti 2018).

The Music Room

Inspired by Laban’s notion of kinesphere, I wanted to create with my interactive system a work that dealt with the size and shape of the space of the kinesphere. In my previous works, I have used Gametrak controllers to make the dancers more aware of the space of the kinesphere. For example, when a dancer was no longer able to move one part of his or her tethered body, he or she was provoked to think about and move other body parts. In other words, the tethered parts of the kinesphere were restrained. However, I wanted to create a new work that somehow more clearly demonstrated the invisible kinesphere around the body.

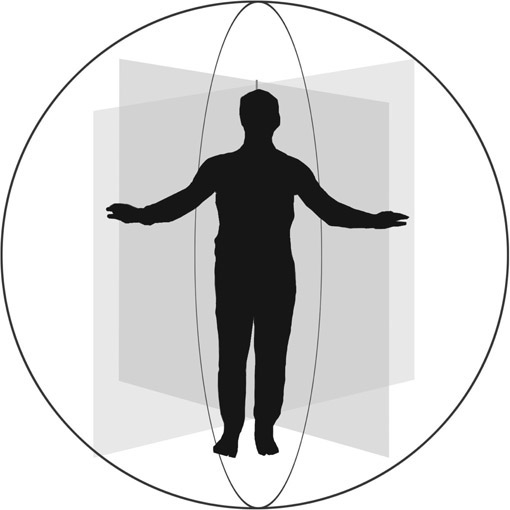

I looked at the possible movement trace-forms drawn in the book Choreutics and planned how to map my sound composition using Laban’s dance notation. I also recreated the trace-forms in 3D space in vvvv.6 However, the more I worked in this direction, the more I felt that it was a mere representation of Laban’s drawings of movement theory. Eventually, I came up with an idea of adding a double enforcement for the dancers by restricting the size of the performance space alongside the use of the Gametrak controllers as a new challenge. Since the kinesphere is a 360° space, I wondered how it would affect a dancer’s perspective when it was cut into quarters (Figure 22.4). This led me to create a piece that had to be performed at the corner of a room.

Figure 22.4

The kinesphere is cut into quarters.

I read Laban’s book A Life for Dance (1975), which consists of his commentaries on his works. I wanted to know his background so that I could understand why he created such a movement theory. In the chapter “The Fool’s Mirror”, Laban wrote about how much he was afraid of the fact that movement could be captured as still images with a camera and lose its physical quality. Perhaps this was behind the basic idea of his choreutic theory as seeing movement as constant “flux”. In the chapter “Illusions”, Laban wrote about how he had struggled to lead his dance troupe during the post-war period without enough financial support and food. Although Laban did not have a hall for rehearsals and had to use meadows instead, this was the period when he further developed the idea of pure movement art with his pupils by dancing in silence without music. While I was reading about choreutic theory, I often wondered why Laban had been obsessed with creating “unity” or “harmony” in movement, which sounded like another way of “controlling” rather than freeing from tradition. However, the more I got to know about his experience in the community with his pupils, the more I came to understand that his goal was not to teach a unified style of dance, but to introduce the most basic principles of human body movement. Therefore, anyone could perform with any kind of movement style. I find Mark Jarecke’s introduction to Laban’s work helps to understand this approach: “Laban looked at dance outside traditions as Kandinsky and Schoenberg did to art and music” (Jarecke 2012).

For The Music Room (Figure 22.5),7 I wanted to recreate a specific scene I had read in the chapter “The Earth”, not as a literal translation but trying to take an excerpt of the story. Laban’s story recounted joyful moments of his childhood as he adventured in the mountains, feeling the majestic earth, and how he incubated his creative ideas inspired by these adventures in the music room of his grandparents’ house by playing a piano. I was drawn to the story in particular because it reminded me of childhood vacations at my own grandparents’ house in the mountains. There was a stream right next to my grandparents’ house, and I swam every summer with my cousins. Visiting my grandparents’ house and playing in nature was definitely one of the most joyful memories from my childhood. It may sound banal or primitive, but it was no doubt simple and true happiness. In The Music Room, therefore, I wanted to create a piece with the most basic principles for creating sound and movement of all my works so far.

Figure 22.5

Live performance of The Music Room at Vivarium Festival 2019 in Porto. Dancer/performer: Katerina Foti.

Source: João Pádua, Vivarium Festival 2019, © Saco Azul and Maus Hábitos.

I used a piano sound because of Laban’s story, although I do not usually use musical instruments in my sound compositions. I do not feel it is right for me to mess around with musical instruments since I am not a player. While hesitating to use piano, I remembered what Morton Feldman said:

This inspired me to set the core choreographic task for this piece: Once you trigger sound, let the sound be played out until it lasts before you move again. In other words, the dancer needed to concentrate on when to move according to the length of sound she had triggered, and the triggered sounds unfolded by themselves according to the intervals created by the dancers. The dancer was not attempting to respond emotionally, but had to think about creating stillness until the note decayed. Here, the sound composition also worked as another restriction for the dancer. As a consequence, this relationship evolved the dramaturgy through a tension between the dancer and the piano notes. Based on this idea I played some chords I liked on a piano and listened to the overtones and lengths of resonance. I then recorded each note from the chords until the sound naturally decayed. Finally, I loaded the recorded piano notes in Max using poly~ objects to be triggered randomly.

I set up four Gametrak controllers – two on the ceiling and two on the floor. Based on Laban’s notation system within the kinesphere I initially mapped the sound to be triggered when the dancer held her limbs towards forward, right forward, left forward, high forward, high right forward, high left forward, deep forward, deep right forward and deep left forward, because these were the possible directions of movement while standing at the corner of a room. For the first rehearsal, I asked my collaborating dancer Foti to stand in the corner of the room and to tether the cables of the Gametrak controllers onto each of her limbs. Then I asked her to move her limbs one by one. I thought this would be an effective introduction for the audience to demonstrate the fact that each of her limbs were triggering sound as she moved. However, Foti said that where I had mapped the sounds was not natural for her dance style. Laban wrote his theory in the early 1900s, just as modern dance started to be established as a form. He thus used the centre of the body as the axis in his notation system, in relation to traditional ballet principles. But in current contemporary dance practice the axis of the body is instead grounded, following the natural relationship between gravity and the body. When Foti tried to move only one arm, it was not a problem. However, she felt very awkward moving only one leg in the standing position.

After we went through the entire composition twice, Foti suggested leaning against the wall behind her for the very beginning part rather than free standing. She explained that moving only one part of her limb while standing could be one way of applying a restriction to her, but it did not feel natural based on how she had been trained. Therefore, for the third rehearsal she tried the beginning part while crouched down to see how she could move her legs from that position. Eventually, we decided to start the composition with the dancer sitting down and holding the column behind her. In this way, she could fix her hands holding the column more naturally while moving her legs and, in return, not accidentally trigger sounds with her hands. I mapped the piano notes again according to this position.8

Once we had established the right position from which to begin the composition, the choreographic ideas for the next parts came very quickly. In the fifth rehearsal, the dancer also tried upside down positions leaning her legs against the wall. This was another interesting position in which she could fix her hands so as not to trigger unwanted sounds. In the end we no longer cared about Laban’s well-structured notation system within the cube-shape kinesphere, but designated our own positions that were more suitable for Foti’s style of dance.

I decided to present this piece as a dance film to show the intimate relationship between the body, the space and my choreographic sound composition with the viewpoints that I wanted to show. I experience dance by looking primarily at the “effort” of movement, not only its outline. That effort provokes or relates to certain emotions, which I find to be quite a different way of expression from acting. I tried to capture the effort of moving with my rules and the space as a “hidden feature” of the choreography just as Laban highlighted the intimate relationship between space and movement in his choreutic theory (Ullmann 2011: 3–4).

Conclusion

In creating my sound compositions I have sought ways to integrate interactive technology into the choreographic process. I have therefore studied some choreographic methods to understand how contemporary dance works are structured. Locus was where I tested whether my compositional approach was convincing for my collaborating dancers. Throughout this piece, I observed how restriction affected the dancers’ awareness of their bodies and the performance space. For me, the later work The Music Room was the best-demonstrated piece in terms of using restrictions with interactive sound synthesis. Here the sound triggered by the dancer also restricted her movement, creating stillness, and the corner of the room became a physical enforcement that restricted the size and shape of her kinesphere.

With this compositional method, I was sometimes asked whether my role had become that of a choreographer as well. However, my intention was to introduce the collaborative model from the field of contemporary dance to the field of computer music and to adopt it into my compositional process for sound. Therefore, it is hard to clarify the roles of composer, choreographer and performer in the traditional sense. This compositional approach came about because I wanted to create a sound and dance collaboration in which each collaborator could contribute their expertise to the creative process, rather than one medium determining the other. Therefore, the Gametrak controllers were used not only as an interface but also as a common medium in which to think and work on the compositional process together. Both abstract sound and choreographic ideas were bridged through a concrete object – co-opting the affordances of the restrictive motion-tracking technology – to successfully conduct this interdisciplinary collaborative composition. Ultimately, not just the technological integration, but the holistic collaborative compositional cycle can be considered as an interdisciplinary compositional act.

References

Book

- Au, S. (2002) Ballet and Modern Dance (2nd ed.). London: Thames & Hudson.

- Copeland, R. (2004) Merce Cunningham: The Modernizing of Modern Dance. New York and London: Routledge.

- Feldman, M. (2000) Give My Regards to Eighth Street: Collected Writings of Morton Feldman (ed. B.H. Friedman). Cambridge, MA: Exact Change.

- Foster, S.L. (2010) Choreographing Your Move. In: S. Rosenthal (ed.) Move Choreographing You: Art and Dance since the 1960s. London and Manchester: Hayward Pub.

- Laban, R. (1975) A Life for Dance. London: Macdonald & Evans.

- Reich, S. (1973) Notes on Music and Dance. In: Writings about Music. Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

- Rosenberg, S. (2017) Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- Salter, C. (2010) Entangled: Technology and the Transformation of Performance. London and Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Spier, S. (2011) William Forsythe and the Practice of Choreography: It Starts from Any Point. London: Routledge.

- Ullmann, L. (2011) Choreutics. Hampshire: Dance Books.

Journal article

- Birringer, J. (2008) After Choreography. Performance Research. 13(1). Routledge. pp. 118–122. doi: 10.1080/13528160802465649.

- Clark, J.O.; Ando, T. (2014) Geometry, Embodied Cognition and Choreographic Praxis. International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media. 10(2). Routledge. pp. 179–192. doi: 10.1080/14794713.2014.946285.

- deLahunta, S. (2001) Invisibility/Corporeality. NOEMA. Available online: https://noemalab.eu/ideas/essay/invisibilitycorporeality/ [Last Accessed 12/02/18].

- deLahunta, S. (2006) Willing Conversations: The Process of Being between. Leonardo. 39(5). The MIT Press. pp. 479–481. doi: 10.2307/20206301.

- Emmerson, S. (1989) Composing Strategies and Pedagogy. Contemporary Music Review. 3(1). Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 133–144. doi: 10.1080/07494468900640091.

- Forsythe, W.; Kaiser, P. (1999) Dance Geometry. Performance Research. 4(2). Routledge. pp. 64–71. doi: 10.1080/13528165.1999.10871671.

- Wilson-Bokowiec, J.; Bokowiec, M.A. (2006) Kinaesonics: The Intertwining Relationship of Body and Sound. Contemporary Music Review. 25(1–2). Routledge. pp. 47–57. doi: 10.1080/07494460600647436.

Personal communication

- Foti, K. (2018) Personal communication, 15 October.

- Foti, K.; Pandermali, N. (2015) Personal communication, 7 September.

Website

- Forsythe, W. (n.d.) Choreographic Objects. Available online: www.williamforsythe.com/essay.html [Last Accessed 18/06/19].

Video

- Jarecke, M. (2012) Introduction to Laban’s Space Harmony [Lecture]. Available online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=p-B_E3loAto&t=15s [Last Accessed 02/06/18].

- McGregor, W. (2012) A Choreographer’s Creative Process in Real Time. TED Global. Available online: www.ted.com/talks/wayne_mcgregor_a_choreographer_s_creative_process_in_real_time?utm_campaign=tedspread–b&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare [Last Accessed 12/02/18].

- Nikolais, A. (1974) Interviewed by James Day for Day at Night. PBS, 29 November. Available online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=atmek4ra-UU [Last Accessed 27/05/18].

Attended conference

- Moving Matter(s): On Code, Choreography and Dance Data, Fiber Festival. (2017) Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Artwork

- 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959) by Allan Kaprow.

- Eidos: Telos (1995) by William Forsythe, Thom Willem and Joel Ryan, Frankfurt Ballet Company.

- Fearful Symmetry (2012) by Ruairi Glynn.

- Green Light Corridor (1970) by Bruce Nauman.

- Improvisation Technologies (2011) by The Forsythe Company and ZKM.

- Mind and Movement from the Project Choreographic Thinking Tools (2013) by Wayne McGregor | Random Dance.

- Tower (1965) by Alwin Nikolais.

- Variations V (1965) by John Cage, Merce Cunningham, David Tudor, Gordon Mumma, Carolyn Brown, Barbara Dilley.

![22 Sound – [object] – dance: a holistic approach to interdisciplinary composition](https://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/cover/cover/20200920/EB9781000069945.jpg)